Aging in the world: Existential Perspectives on Social Work with

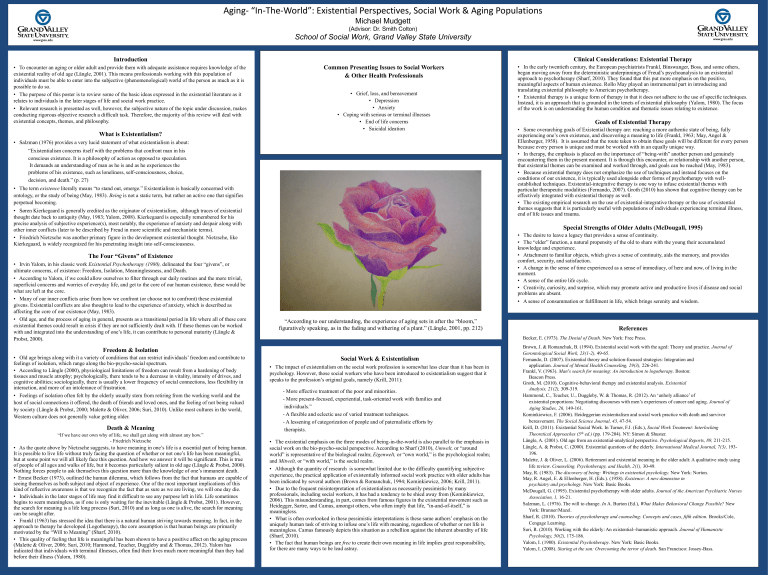

Aging- “In-The-World”: Existential Perspectives, Social Work & Aging Populations

Michael Mudgett

(Advisor: Dr. Smith Colton)

School of Social Work, Grand Valley State University

Introduction

• To encounter an aging or older adult and provide them with adequate assistance requires knowledge of the existential reality of old age (Längle, 2001). This means professionals working with this population of individuals must be able to enter into the subjective (phenomenological) world of the person as much as it is

Figure 1.

• The purpose of this poster is to review some of the basic ideas expressed in the existential literature as it relates to individuals in the later stages of life and social work practice.

• Relevant research is presented as well, however, the subjective nature of the topic under discussion, makes conducting rigorous objective research a difficult task. Therefore, the majority of this review will deal with existential concepts, themes, and philosophy.

What is Existentialism?

• Salzman (1976) provides a very lucid statement of what existentialism is about:

“Existentialism concerns itself with the problems that confront man in his conscious existence. It is a philosophy of action as opposed to speculation.

It demands an understanding of man as he is and as he experiences the problems of his existence, such as loneliness, self-consciousness, choice, decision, and death.” (p. 27)

• The term

existence

literally means “to stand out, emerge.” Existentialism is basically concerned with ontology, or the study of being (May, 1983).

Being

is not a static term, but rather an active one that signifies perpetual becoming.

• Søren Kierkegaard is generally credited as the originator of existentialism, although traces of existential thought date back to antiquity (May, 1983; Yalom, 2008). Kierkegaard is especially remembered for his precise analysis of subjective experience(s), most notably, the experience of anxiety and despair along with other inner conflicts (later to be described by Freud in more scientific and mechanistic terms).

• Friedrich Nietzsche was another primary figure in the development existential thought. Nietzsche, like

Kierkegaard, is widely recognized for his penetrating insight into self-consciousness.

The Four “Givens” of Existence

• Irvin Yalom, in his classic work

Existential Psychotherapy (1980),

delineated the four “givens”, or ultimate concerns, of existence: Freedom, Isolation, Meaninglessness, and Death.

• According to Yalom, if we could allow ourselves to filter through our daily routines and the more trivial, superficial concerns and worries of everyday life, and get to the core of our human existence, these would be what are left at the core.

• Many of our inner conflicts arise from how we confront (or choose not to confront) these existential givens. Existential conflicts are also thought to lead to the experience of anxiety, which is described as affecting the core of our existence (May, 1983).

• Old age, and the process of aging in general, presents as a transitional period in life where all of these core existential themes could result in crisis if they are not sufficiently dealt with. If these themes can be worked with and integrated into the understanding of one’s life, it can contribute to personal maturity (Längle &

Probst, 2000).

Freedom & Isolation

• Old age brings along with it a variety of conditions that can restrict individuals’ freedom and contribute to feelings of isolation, which range along the bio-psycho-social spectrum.

• According to Längle (2000), physiological limitations of freedom can result from a hardening of body tissues and muscle atrophy; psychologically, there tends to be a decrease in vitality, intensity of drives, and cognitive abilities; sociologically, there is usually a lower frequency of social connections, less flexibility in interaction, and more of an intolerance of frustration.

• Feelings of isolation often felt by the elderly usually stem from retiring from the working world and the host of social connections it offered, the death of friends and loved ones, and the feeling of not being valued by society (Längle & Probst, 2000; Malette & Oliver, 2006; Suri, 2010). Unlike most cultures in the world,

Western culture does not generally value getting older.

Death & Meaning

“If we have our own why of life, we shall get along with almost any how.”

- Friedrich Nietzsche

• As the quote above by Nietzsche suggests, to have meaning in one’s life is a essential part of being human.

It is possible to live life without truly facing the question of whether or not one’s life has been meaningful, but at some point we will all likely face this question. And how we answer it will be significant. This is true of people of all ages and walks of life, but it becomes particularly salient in old age (Längle & Probst, 2000).

Nothing forces people to ask themselves this question more than the knowledge of one’s immanent death.

• Ernest Becker (1973), outlined the human dilemma, which follows from the fact that humans are capable of seeing themselves as both subject and object of experience. One of the most important implications of this kind of reflective awareness is that we recognize the fact that as sure as we are living, we will one day die.

• Individuals in the later stages of life may find it difficult to see any purpose left in life. Life sometimes begins to seem meaningless, as if one is only waiting for the inevitable (Längle & Probst, 2001). However, the search for meaning is a life long process (Suri, 2010) and as long as one is alive, the search for meaning can be sought after.

• Frankl (1963) has stressed the idea that there is a natural human striving towards meaning. In fact, in the approach to therapy he developed (Logotherapy), the core assumption is that human beings are primarily motivated by the “Will to Meaning” (Sharf, 2010).

• This quality of feeling that life is meaningful has been shown to have a positive affect on the aging process

(Malette & Oliver, 2006; Suri, 2010; Hammond, Teucher, Duggleby and & Thomas, 2012). Yalom has indicated that individuals with terminal illnesses, often find their lives much more meaningful than they had before their illness (Yalom, 1980).

A

A

B

B

Common Presenting Issues to Social Workers

& Other Health Professionals

• Grief, loss, and bereavement

• Depression

D

• Anxiety

• Coping with serious or terminal illnesses

C

• End of life concerns

• Suicidal ideation

C

“According to our understanding, the experience of aging sets in after the “bloom,” figuratively speaking, as in the fading and withering of a plant.” (Längle, 2001, pp. 212)

Social Work & Existentialism

• The impact of existentialism on the social work profession is somewhat less clear than it has been in psychology. However, those social workers who have been introduced to existentialism suggest that it

C) speaks to the profession’s original goals, namely (Krill, 2011):

D)

- More effective treatment of the poor and minorities.

- More present-focused, experiential, task-oriented work with families and individuals.”

- A flexible and eclectic use of varied treatment techniques.

- A lessening of categorization of people and of paternalistic efforts by therapists. social work on the bio-psycho-social perspective. According to Sharf (2010),

Umwelt,

or “around world” is representative of the biological realm;

Eigenwelt,

or “own world,” is the psychological realm; and

Mitwelt,

or “with world,” is the social realm.

• Although the quantity of research is somewhat limited due to the difficulty quantifying subjective experience, the practical application of existentially informed social work practice with older adults has been indicated by several authors (Brown & Romanchuk, 1994; Kominkiewicz, 2006; Krill, 2011).

• Due to the frequent misinterpretation of existentialism as necessarily pessimistic by many professionals, including social workers, it has had a tendency to be shied away from (Kominkiewicz,

2006). This misunderstanding, in part, comes from famous figures in the existential movement such as

Heidegger, Sartre, and Camus, amongst others, who often imply that life, “in-and-of-itself,” is meaningless.

• What is often overlooked in these pessimistic interpretations is these same authors’ emphasis on the uniquely human task of striving to infuse one’s life with meaning, regardless of whether or not life is meaningless. Camus famously depicts this situation as a rebellion against the inherent absurdity of life

(Sharf, 2010).

• The fact that human beings are

free

to create their own meaning in life implies great responsibility, for there are many ways to be lead astray.

Clinical Considerations: Existential Therapy

• In the early twentieth century, the European psychiatrists Frankl, Binswanger, Boss, and some others, began moving away from the deterministic underpinnings of Freud’s psychoanalysis to an existential approach to psychotherapy (Sharf, 2010). They found that this put more emphasis on the positive, meaningful aspects of human existence. Rollo May played an instrumental part in introducing and translating existential philosophy to American psychotherapy.

• Existential therapy is a unique form of therapy in that it does not adhere to the use of specific techniques.

Instead, it is an approach that is grounded in the tenets of existential philosophy (Yalom, 1980). The focus of the work is on understanding the human condition and thematic issues relating to existence.

Goals of Existential Therapy

• Some overarching goals of Existential therapy are: reaching a more authentic state of being, fully experiencing one’s own existence, and discovering a meaning to life (Frankl, 1963; May, Angel &

Ellenberger, 1958). It is assumed that the route taken to obtain these goals will be different for every person because every person is unique and must be worked with in an equally unique way.

• In therapy, the emphasis is placed on the importance of “being-with” another person and genuinely encountering them in the present moment. It is through this encounter, or relationship with another person, that existential themes can be examined and worked through, and goals can be reached (May, 1983).

• Because existential therapy does not emphasize the use of techniques and instead focuses on the conditions of our existence, it is typically used alongside other forms of psychotherapy with wellestablished techniques. Existential-integrative therapy is one way to infuse existential themes with particular therapeutic modalities (Fernando, 2007). Groth (2010) has shown that cognitive therapy can be effectively integrated with existential therapy as well.

• The existing empirical research on the use of existential-integrative therapy or the use of existential themes suggests that it is particularly useful with populations of individuals experiencing terminal illness, end of life issues and trauma.

Special Strengths of Older Adults (McDougall, 1995)

• The desire to leave a legacy that provides a sense of continuity.

• The “elder” function, a natural propensity of the old to share with the young their accumulated knowledge and experience.

• Attachment to familiar objects, which gives a sense of continuity, aids the memory, and provides comfort, security, and satisfaction.

• A change in the sense of time experienced as a sense of immediacy, of here and now, of living in the moment.

• A sense of the entire life cycle.

• Creativity, curiosity, and surprise, which may promote active and productive lives if disease and social problems are absent.

• A sense of consummation or fulfillment in life, which brings serenity and wisdom.

References

Becker, E. (1973). The Denial of Death. New York: Free Press.

Brown, J. & Romanchuk, B. (1994). Existential social work with the aged: Theory and practice. Journal of

Gerontological Social Work, 23(1-2), 49-65.

Fernando, D. (2007). Existential theory and solution-focused strategies: Integration and application. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 29(3), 226-241.

Frankl, V. (1963). Man ’ s search for meaning: An introduction to logotherapy. Boston:

Beacon Press.

Groth, M. (2010). Cognitive-behavioral therapy and existential analysis. Existential

Analysis, 21(2), 309-319.

Hammond, C., Teucher, U., Duggleby, W. & Thomas, R. (2012). An ‘unholy alliance’ of existential proportions: Negotiating discourses with men’s experiences of cancer and aging. Journal of

Aging Studies, 26, 149-161.

Kominkiewicz, F. (2006). Heideggerian existentialism and social work practice with death and survivor bereavement. The Social Science Journal, 43, 47-54.

Krill, D. (2011). Existential Social Work.

In Turner, F.J. (Eds.), Social Work Treatment: Interlocking

Theoretical Approaches (5 th ed.) (pp. 179-204). NY: Simon & Shuster.

Längle, A. (2001). Old age from an existential-analytical perspective. Psychological Reports, 89, 211-215.

Längle, A. & Probst, C. (2000). Existential questions of the elderly. International Medical Journal, 7(3), 193-

196.

Malette, J. & Oliver, L. (2006). Retirement and existential meaning in the older adult: A qualitative study using life review. Counseling, Psychotherapy, and Health, 2(1), 30-49.

May, R. (1983). The discovery of being: Writings in existential psychology. New York: Norton.

May, R. Angel, E. & Ellenberger, H. (Eds.). (1958). Existence: A new dimension in psychiatry and psychology. New York: Basic Books.

McDougall, G. (1995). Existential psychotherapy with older adults. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses

Association, 1, 16-21.

Salzman, L. (1976). The will to change. In A. Burton (Ed.), What Makes Behavioral Change Possible?

New

York: Brunner/Mazel.

Sharf, R. (2010). Theories of psychotherapy and counseling: Concepts and cases, fifth edition. Brooks/Cole,

Cengage Learning.

Suri, R. (2010). Working with the elderly: An existential--humanistic approach. Journal of Humanistic

Psychology, 50(2), 175-186.

Yalom, I. (1980). Existential Psychotherapy . New York: Basic Books.

Yalom, I. (2008). Staring at the sun: Overcoming the terror of death . San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.