Self Care Without Self-Injury - Canadian Counselling and

advertisement

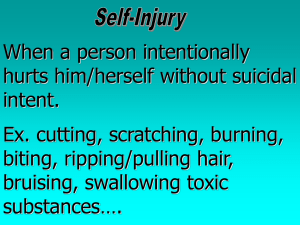

Self Care Without Injury Canadian Counselling and Psychotherapy Association (CCPA) Annual Conference May 11-14, 2010 Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island Presented By Nancy Buzzell, Ph. D., Licensed Psychologist University of New Brunswick Counselling Services Sarah Smith, Research Assistant Mount Allison University As Laura entered her house she slammed the door behind her. It had been a bad day, a very bad day. Things at school had been terrible. As Laura locked the door to her bedroom, she was so angry that her whole body was shaking. All she wanted to do was cry, but no tears would come. Laura knew what she needed to do to feel better. She took a small wooden box from under her bed. Carefully lifting its lid, she removed the contents, a single edged razor blade and a packet of gauge bandages. Sitting on the carpeted floor, gently rocking back and forth, she stared at the silver blade in her hand. She needed to do it, she told herself. It was the only way she could feel better, feel normal again. Laura felt no pain as she made the first of several cuts on her left forearm. She watched as the blood spilled from the cuts and dripped down her arm. It felt warm and soothing on her cold skin. After cutting herself in three or four places, Laura wiped the blade clean with a piece of gauze and placed it back in its box. She wrapped her wounds tightly with the bandages, only then feeling the sting. Although she felt tired and drained, she also felt much better. Cutting herself had worked, just as it always did. Alderman, T. (1997). The scarred soul. Oakland, CA: Harbinger Publishers. Self Injurious Behavior All behavior involving the deliberate infliction of direct physical harm to one’s body without the intent to die. Simeon, D., & Favazza, A. (2001). Self-Injurious behaviors: Phenomenology and assessment. In Simeon & E. Hollander (Eds.), Self-injurious behaviors: Assessment and treatment (pp. 1-28). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. Self Injurious Behavior (SIB) Breaking bones Burning (8%) Biting Hitting/bruising (3%) High risk activity Needle sticking Cutting (86%) Scratching Hair pulling Head Banging Picking Skin picking Starving self Other (3%) Gratz, K. L.. (2006). Risk factors for deliberate self-harm among female college students: The role and interaction of childhood maltreatment, emotional in-expressivity and affect intensity/reactivity. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 76 (20), 238-50. Historical Trends Before 1990: Prevalent among individual with serious mental health issues and abuse/trauma backgrounds After 1990: Prevalent among school age children, adolescents & university students Rate has risen by 150% over the last 20 years across a broad spectrum of society Enns, K. (2008). Self injury behaviour in youth: Issues and strategies. Winnipeg, MB: Crisis & Trauma Resource Institute Inc. Who Does It Affect? Percent Population 21% ClinicalF/M) Briere & Gil (1998) ** 7% University F/M) Gollust et al (2008) 38% University (F/M) Gratz et al (2002) ** 37% University (F) Gratz (2006) 44% University (M) Gratz & Chapman (2007) 13.89% High School (F) 13.9% Researchers Ross & Heath (2003) Community (F) Ross et al (2009) Rates of SIB are estimated to be between 12%-38% Meta-analysis: 8 Functions of Self Injury (Cutting) Behavioral or the reinforcement of destructive behavior & the linking of injury with self care Systemic or a way to express dysfunctional family or environment Suicidal or a suicide replacement Sexual or a result of conflicts over sexuality & menarche Suyemoto, K. L., & MacDonald, M.L. (1995). Self cutting in female adolescents. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training. 32(1), 162-171. Meta-analysis: 8 Functions of Self Injury (Cutting) Expression or a need to express or externalize overwhelming of anger, anxiety or pain Control or an attempt to control affect or need Depersonalization or a way to end or cope with not feeling present & in one’s own body Boundaries or an attempt to create distinction between self & others Suyemoto, K. L., & MacDonald, M.L. (1995). Self cutting in female adolescents. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training. 32(1), 162-171. General Risk Factors Feelings of powerlessness Feelings of being alone or isolated Difficulty recognizing/communicating feelings Few, if any, alternative coping behaviours Few self care or self soothing skills History of physical, sexual or mental abuse A likable, sometimes high achieving person with other problems. Levenkron, S. (1997). Cutting: Understanding & overcoming self mutilation. NY: WW Norton & Company. Specific Risk Factors Characteristic Researchers Depression and anxiety Hoff and Muehlenkamp (2009) Peer invalidation Adrian (2010) Family invalidation Adrian (2010) Academic difficulties Mahadevan, Hawton & Casey (2010) Disordered eating Ross, Heath & Toste (2009) History of drug use Saules, Cranford & Eisenberg (2010) Sexuality Identity Saules, Cranford & Eisenberg (2010) Social Context Recent research with university students who self-injure found that: 43.6% of students reported that their behaviour was learned socially 86% of participants knew someone who self injured 74% had at least one friend who self injured 65% had talked to their friends about it 17.4% had engaged in it in front of friends 4.3% had engaged in it as a group with friends Heath, N. L., Ross, S., Toste, J. R., Charlebois, A. & Nedecheva, T. (2009) Retrospective analysis of social factors and non suicidal self-injury among young adults. Canadian Journal of Behavioral Science, 41, 180-186. The Dissociation Factor Dissociative: Disconnected from parents, others &/or self. Not secretive about cutting & at times damages self in full view of others. Attention is gratifying (secondary gain) in it’s own right. Non-Dissociative: Physical pain becomes a cure for emotional pain. Usually starts with feelings of anger, anxiety or panic. Person “stumbles” upon self injury and discovers it relieves their emotional state. Instant relief. Endorphin rush. Levenkron, S. (1997). Cutting: Understanding & overcoming self mutilation. NY: WW Norton & Company. Often Starts on an Impulse May start because of others in life who are self injuring May learn about self injury through tv shows, music videos, chat rooms May be accidental: injury then person felt soothed May be result of extreme agitation/rage & becomes pattern of self soothing Enns, K. (2008). Self injury behaviour in youth: Issues and strategies. Winnipeg, MB: Crisis & Trauma Resource Institute Inc. Self Assessment Tool 1. If I do this, will it hurt or harm my body? If I answer “no” would other people agree with me? 2. If I do this, will I need help coping with the repercussions? Will I need to see a doctor, nurse, counsellor? 3. If I do this, will the people I care about be upset? Frustrated? Frightened? Appalled? 4. If I do this, will I lose an opportunity to reach my goals in life? Drop out of school? Miss an important opportunity? If you answer yes to just one, you are self harming. Haswell, D., & Graham, M. (2008). 5th Edition. Overcoming self-abuse. Hamilton, ON: S.A.F.E. in Canada. Clinical Assessment Frequency, duration, severity, medical history & possible complications Reasons or purpose of SIB Determining client’s stopping point Education about function (both +ve & -ve) Providing appropriate alternatives Ever thought about suicide? Wester, K. & Trepal, H. (2005). Working with clients who self injure: Providing alternatives. Journal of College Counseling, 8, 180-189. Why People Say It “Works” It calms me person down It helps me feel more in control It makes me feel “alive” Haswell, D., & Graham, M. (2008). 5th Edition. Overcoming self-abuse. Hamilton, ON: S.A.F.E. in Canada. Why We Think It Works Expresses feelings Releases negative emotions & tension Makes emotional pain clearer Punishment Ends dissociation Results in a rush or a high Communicates something to other people Gratz, K. & Chapman, A. (2009). Freedom from Self-Harm. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publishers. How it Works Like other injuries, it brings about the release of endorphins which are natural pain killers that calm down the central nervous system. It triggers (or ends) dissociation which is the mind’s way of producing a state of trance in which emotion & pain can be disregarded. Haswell, D., & Graham, M. (2008). 5th Edition. Overcoming self-abuse. Hamilton, ON: S.A.F.E. in Canada. Reasons it Doesn’t Work Undermines a person’s mental, physical, social & spiritual well-being Does nothing to solve problem(s) Offers only temporary relief Often followed by guilt & shame Haswell, D., & Graham, M. (2008). 5th Edition. Overcoming self-abuse. Hamilton, ON: S.A.F.E. in Canada. www.safeincanada.org E SAFE Scale F A Safe: No trigger Ascending: Starting to feel triggered Feeling: Out of control & urge to self injury Extremely unsafe & strong urge to self injure S Trigger Baseline Baseline Self abuse does not allow the person to return to baseline. Next time person start s off at a higher trigger point. Addiction Model Negative Emotions Alienation, Anger, Depression, Frustration, Rejection, Sadness Negative Effects Tension Shame, guilt, depression Inability to control emotions & thoughts of self injury Positive Effects Dissociation Endorphins present, tension & negative emotions reduced Coping mechanism to reduce tension & later physical pain Self Injury Burning, cutting, hitting, pulling hair, scratching Alderman, T. (1997). The scarred soul. Oakland, CA: Harbinger Publishers. Questions We Can Ask 1. Think back to a time when you self injured. List three of the most intense emotions you had before you acted. 2. Describe how you felt when you began to think about hurting yourself. Did your feelings change as you got closer to injuring yourself? 3. Describe what you went through when you self injured. Did your feelings change throughout the process? Alderman, T. (1997). The scarred soul. Oakland, CA: Harbinger Publishers. More Questions 4. What happened after you hurt yourself. How did you feel? Calm? Tired? Peaceful? Anxious? 5. List the ways your self injury contributed to a feeling of relief. How do you define relief? 6. How long did it take after hurting yourself to feel bad again? Alderman, T. (1997). The scarred soul. Oakland, CA: Harbinger Publishers. How Does it Function for the Client? How does it help? How does not help? Makes me feel better I have to do more for it to work Helps me feel in control I feel bad about myself Takes my mind off things I have to hide the scars It upsets my boyfriend Client’s Self Injury Log 1. Time & date of self injury 2. Situation or trigger 3. Thoughts & feelings before self injury 4. Location/room where self injury took place 5. Wounds: How many? Where on body? Use of tool? 6. Thoughts & feelings after self injury 7. Reactions of others to the self injury Enns, K. (2008). Self injury behaviour in youth: Issues and strategies. Winnipeg, MB: Crisis & Trauma Resource Institute Inc. Stopping Point When or how does client know to stop? Does client stop when they begin to feel pain? When does the client reach a stopping point? Visual aspect? Sensation of pain or numbing? Wester, K. & Trepal, H. (2005). Working with clients who self injure: Providing alternatives. Journal of College Counseling, 8, 180-189. Alternatives to Self Injury Relaxation training Containment strategies Mindfulness, emotional regulation & distress tolerance skills (DBT) Physical activity/yoga/sports Communication with others Negative replacement behaviors Alternatives to Self Injury Aggression/anger Tear up newspaper or phone book. ` Throw ice cubes, rocks or eggs at a wall. Punch a pillow. Restlessness Workout, go for a run, walk or bike ride. Clean room. Make noise. Emotional regulation Meditation, belly breathing, repetitive counting, writing Visuals Draw red lines on arms. Draw slash marks on paper. Paint areas on body. Sensations Snap rubber band on wrist. Ice cube on skin. Clod shower. Adapted from Wester, K. & Trepal, H. (2005). Working with clients who self injure: Providing alternatives. Journal of College Counseling, 8, 180-189. Cycle of Self Injury Trigger (Event or situation) Reaction Anger, Shame Action Self Injury Twisted Thinking Automatic Thoughts Feelings Fear, Anger, Sadness -ve Self Talk Cycle of Self Care Trigger (Event or situation) Reaction Relief That Lasts Action Self Care (Without Injury) Am I Thinking Straight? Take a Breath (Slow Down) What am I Feeling? (What Do I Need?) +ve Self Talk (I Can Handle This) Slowing Down the Process The key to recovery is to slow down the process so the client have time to consider what is happening before they respond. Trigger - Thought - Feeling - Self Talk - Action Haswell, D., & Graham, M. (2008). 5th Edition. Overcoming self-abuse. Hamilton, ON: S.A.F.E. in Canada. Trigger - Thought - Feeling - Self Talk - Action What you do in response to an event or situation is within your control & depends on the following: What you think about what is happening? Your emotions are at the time What you believe about yourself, others & the world What you say to yourself about what is happening (Self Talk) Haswell, D., & Graham, M. (2008). 5th Edition. Overcoming self-abuse. Hamilton, ON: S.A.F.E. in Canada. “Untwisting” Your Thoughts Ask yourself am I thinking straight? 1. Am I jumping to conclusions? Without enough information? 2. Am I assuming the worst? Catastrophizing? 3. Am I over generalizing? Always, Everyone, No body? 4. Am I caught in “all or none” thinking? Extremes? Haswell, D., & Graham, M. (2008). 5th Edition. Overcoming self-abuse. Hamilton, ON: S.A.F.E. in Canada. Changing Thought Patterns 1. Identify thought/belief about an event/situation that is leading to unpleasant emotions 2. Evaluate the accuracy of thought/belief Am I taking an extreme view? How else can I think about this event/situation? Am I only looking at the negatives & ignoring the positives? 3. Stop the thought by taking a deep breath & replace the negative thought with a more helpful thought Enns, K. (2008). Self injury behaviour in youth: Issues and strategies. Winnipeg, MB: Crisis & Trauma Resource Institute Inc. Example Start with an event: Traffic jam Self Talk: I am going to be late. This is the third time this week. My boss is going to fire me! (Hot headed thoughts) Take a breath. Are my thoughts helping? What is another way I can think about this? (Cool headed thoughts) Alternative Self Talk: I don’t want this to be a habit. Tomorrow I’ll give myself more time. Managing Relapses Changing thought patterns takes time and practice. Relapses or return to self-injuring patterns are often a part of the change process. If a relapse occurs ask: What do I need to do to get back on track a bit? What has worked before? What have I learned that will help in the future? Self Care Without Self Injury UNB Counselling services Six-2 hr Group Sessions Dr. Nancy Buzzell & Sarah Smith Pre-Group Interview Opportunity for prospective group members to: Meet facilitators See the group room Ask questions Be supported in determining their readiness Pre-Group Interview 1. Does person have the ability to function on a day to day basis? Ideally person should not be in personal crisis or in the midst of a major life transition 2. Does person have the ability to discuss her self injury issues without intense anxiety, dissociation or depressive reactions? When it began, what occurred, extent of current self injury 3. Does person have the ability to function in groups? Have they been in other groups? Does she have any concerns about being in a group? Suggested Questions 1. Introductions 2. Can you tell us about yourself? Year? Program? Living situation? 3. Can you tell us a bit about your self injury? How you are currently doing regarding self injury? 4. Is there anything you are currently doing that helps a bit? 5. What are your reasons for participating in the group? Suggested Questions 6. What do you want to get out of the group? 7. Can you tell us about the support you have for being in the group? Family? Friends? Health care professionals? 8. Do you have any questions or concerns? 9. Do you think you would like to be in the group? 10. Can you commit to all six group sessions? Group 1: Introduction & Safety Introductions Group guidelines Goals for the group Why self injury “works” Harm Reduction & Safety plan Belly breathing practice Check out Homework: Case studies Group Guidelines Attendance Listening & all opinion accepted Confidentiality Self Responsibility & Option to pass Commitment Other: Scents, drinks/snacks Group 2: Understanding Your Behaviour Check In: Reaction to case studies History & function of self injury Addiction model & relapses Slowing down your cycle Progressive muscle relaxation Check out Homework: Increasing your odds Group 3: Coping Check In & Increasing your odds Regulation of impulses Fear of losing control Anxiety relief technique (5,4,3,2,1) Surviving the urge Place in nature visualization Check out Homework: Coping Bank Group 4: Managing Emotions Check In & coping bank Understanding your emotions Emotional expression without self injury Social context of anger Anger management strategies Check out Homework: Self help activities Group 5: Facing Your Life Check In & self help activities Self esteem 101 Self esteem & relationships Boundaries Leaf meditation Check out Homework: Boundary awareness Group 6: Living in the Present Check In & boundary awareness Your relationship with your body Dear body letter Plans to continue self care in the future The rest of your life Raisin meditation Check Out Circle of gifts Web Based Resources www.lifesigns.org.uk www.canadian-health-network.ca www.selfinjury.com www.safeincanada.org www.siari.co.uk www.youthnoise.com www.selfinjury.org.uk/index.html www.dailystrength.org www.recoveryourlife.com www.selfinjury.com/blog References . Adrian, M. (2010) A cumulative risk model of non-suicidal self-injury: Contributions of emotion regulation and contextual invalidation. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering, 70, 44-72. Alderman, T. (1997). The scarred soul: Understanding & ending self inflicted violence. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publishers. Gratz, K., & Chapman, A. (2009). Freedom from self harm. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publishers. Haswell, D., & Graham, M. (2006). Overcoming self abuse. http://ca.geocities.com/safebc/new_page_11.htm. Heath, N. L., Ross, S., Toste, J. R., Charlebois, A. & Nedecheva, T. (2009). Retrospective analysis of social factors and non suicidal self-injury among young adults. Canadian Journal of Behavioral Science, 41, 180-186. Hoff, E. R. & Muehlenkamp, J. J. (2009). Nonsuicidal self-injury in college students: the role of perfectionism and rumination. Suicide and Life Threatening Behaviour, 39, 576-587. References Hollander, M. (2008). Helping teens who cut. NY: Guilford Press. Mahadevan, S., Hawton, K. & Casey, D. (2010). Deliberate self-harm in Oxford university students, 19932005: A descriptive and case-control study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 45, 211-219. Ross, S., Heath, N. L. & Toste, J. (2009). Non-Suicidal self-injury and eating pathology in high school students. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 79, 83–92. Serras, A., Saules, K., Cranford, J. A. & Eisenberg, D. (2010). Self-injury, substance use and associated risk factors in a multi-campus probability sample of students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviours, 24, 119-128. Simeon, D., & Favazza, A. (2001). Self-Injurious behaviors: Phenomenology and assessment. In D. Simeon & E. Hollander (Eds.), Self-injurious behaviors: Assessment and treatment (pp.1-28). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. Wester, K. & Trepal, H. (2005). Working with clients who self injure: Providing alternatives. Journal of College Counseling, 8, 180-189.