prasentation-budapest - Central European University

advertisement

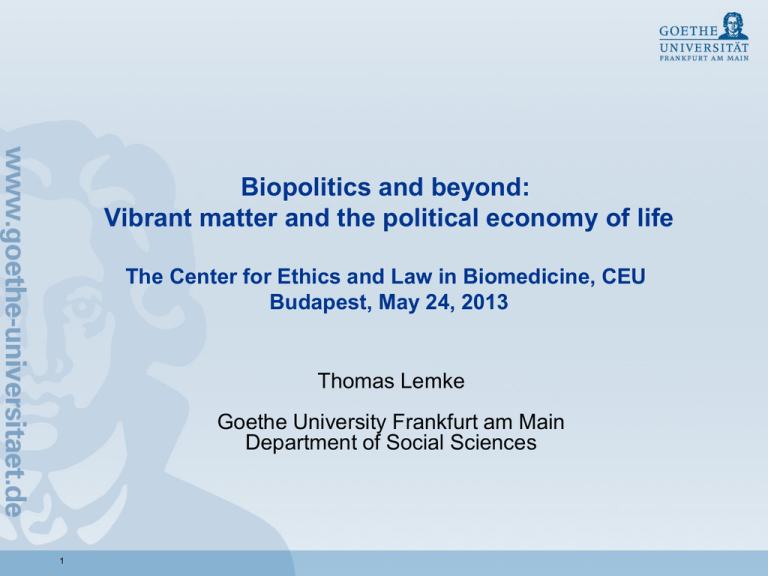

Biopolitics and beyond: Vibrant matter and the political economy of life The Center for Ethics and Law in Biomedicine, CEU Budapest, May 24, 2013 Thomas Lemke Goethe University Frankfurt am Main Department of Social Sciences 1 Introduction Michel Foucault proposes a relational and historical notion of biopolitics against the naturalist tradition (life as the basis of politics) and the politicist reading (life as the object of politics). Two main lines of reception of Foucault’s notion of biopolitics. The first focuses on the meaning of politics, the second on the matter of life. 2 Introduction 1. Challenge I: From biopolitics to biocapital 2. Challenge II: From biopower to thing-power 3. Biopolitics and liberal government 4. The government of things 5. Conclusion 3 Challenge I: From biopolitics to biocapital Policy papers on the “bioeconomy”: • European Commission, New Perspectives on the knowledgebased bio-economy. Conference Report, Brüssel 2005. • OECD, The Bioeconomy To 2030: Designing A Policy Agenda, Paris 2006. 4 Challenge I: From biopolitics to biocapital Cooper, Melina, Life as Surplus. Biotechnology and Capitalism in the Neoliberal Era. Seattle/London 2008. • Peters, Michael A., Bio-informational capitalism, Thesis Eleven, Vol. 110, 2012, pp. 98-111. • Sunder Rajan, Kaushik, Biocapital. The Constitution of Postgenomic Life, Durham/London 2006. • Thacker, Eugene, The global genome. Biotechnology, politics, and culture. Cambridge, MA 2005. • Waldby, Catherine/Cooper, Melinda, The biopolitics of reproduction. Post-fordist biotechnology and women’s clinical labour, Australian Feminist Studies Vol. 23, 2008, pp. 57-73. 5 Challenge I: From biopolitics to biocapital Example: Sunder Rajan (2006): Biocapital. The Constitution of Postgenomic Life. [O]n the one hand, what forms of alienation, exploitation, and divestiture are necessary for a “culture of biotechnology innovation” to take root? On the other hand, how are individual and collective subjectivities and citizenships both shaped and conscripted by these technologies that concern “life itself”? (Ibid., 78) 6 Challenge I: From biopolitics to biocapital Stefan Helmreich: Species of biocapital, Science as Culture, Vol. 14, 2008, pp. 463-478: Two cluster of theories: (a) a Marxist-feminist cluster which is concerned with production and reproduction and focuses on the analysis of biological matter; (b) a Weberian-Marxist cluster paying closer attention to questions of meaning and concerned with how ‘‘relations of production are described alongside accountings of ethical subjectivity’’ (Helmreich 2008, 471). 7 Challenge I: From biopolitics to biocapital Birch, Kean/Tyfield, David: Theorizing the bioeconomy: biovalue, biocapital or... What? Science, Technology and Human Values, (in print) Critical points in the literature on biocapital: (1) There is an issue with how to link “vitality” and value, especially in the concept of biovalue. (2) the distinction between economic value and ethical values tends to collapse in many works on biocapital or the bioeconomy. (3) Marxist concepts like surplus, capital, value are only selectively adopted without adequately addressing their original formulations in Marxism 8 Challenge II: From biopower to thing-power • Alaimo, Stacy/Hekman, Susan (eds.) (2008): Material Feminisms. Bloomington and Indianapolis, Indiana University Press • Barad, Karen (2007): Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. Durham and London: Duke University Press. • Bennett, Jane (2010): Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things. Durham and London: Duke University Press • Braun, Bruce/Whatmore, Sarah (eds.) (2010): Political Matter: Technoscience, Democracy and Public Life. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. • Coole, Diane/Frost, Samantha (eds.) (2010): New Materialism: Ontology, Agency, and Politics. Durham and London: Duke University Press. 9 Challenge II: From biopower to thing-power Example: Jane Bennett, Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things 2010 By ‘vitality’ I mean the capacity of things – edibles, commodities, storms, metals - not only to impede or block the will and designs of humans but also to act as quasi-agents or forces with trajectories, propensities, or tendencies of their own.” (2010: viii) 10 Biopolitics and liberal government The theme was to have been “biopolitics”, by which I meant the attempt, starting from the eighteenth century, to rationalize the problems posed to governmental practice by phenomena characteristic of a set of living beings forming a population: health, hygiene, birthrate, life expectancy, race …. (Foucault 2008, 317) • Foucault understands liberalism as a specific art of leading human beings, which is oriented toward the population as a new political figure, and disposing over the political economy as a technique of intervention. • The eighteenth century emergence of political economy, and of the population cannot be separated from the beginnings of modern biology 11 Biopolitics and liberal government Foucault defines “liberalism as the general framework of biopolitics” (Foucault 2008: 22), “Vital politics” means a form of politics “that considers all factors upon which happiness, well-being, and satisfaction in reality depend” (Rüstow 1955: 70). 12 The government of things Guillaume de la Perrière: Le Miroire politique, œuvre non moins utile que necessaire à tout monarches, roys, princes, seigneurs, magistrats, et autres surintendants et gouverneurs de Republicques (Lyon 1555). Government as “the right dispositions of things arranged so as to lead to a suitable end” (Foucault 2007: 96). 13 The government of things “The things government must be concerned about, La Perrière says, are men in their relationships, bonds, and complex involvements with things like wealth, resources, means of subsistence, and, of course, the territory with its borders, qualities, climate, dryness, fertility, and so on. ‘Things’ are men in their relationships with things like customs, habits, ways of acting and thinking. Finally, they are men in their relationships with things like accidents, misfortunes, famine, epidemics, and death.” (Foucault 2007: 96) 14 The government of things (1) The art of government does not conceive of interactions between two stable and fixed entities – “humans” and “things”. (2) “To govern means to govern things” (Foucault 2007: 97). Since there is no pre-given and fixed political borderline between humans and things, it is possible to state that „humans“ are governed as „things“. “The government of things replaces the older government of the souls and the bodies. The question is no longer, as it was with the Christian authors, about the legitimate use of power; nor is it the one raised by Machiavelli of the exclusive appropriation of power. The question is now about the intensive use of the totality of forces available. So, we note a passage from the right of power to a physics of power (Passage du droit de la force à la physique des forces).”(Senellart 1995: 42-43; emphasis in original; translation TL) 15 The government of things (3) Government enacts a mode of power very different from sovereignty: “it is not a matter of imposing a law on men, but of the disposition of things, that is to say, of employing tactics rather than laws, or, of as far as possible employing laws as tactics; arranging things so that this or that end may be achieved through a certain number of means” (Foucault 2007: 99). 16 Conclusion The conceptual shift to a “government of things” not only makes it possible to extend the territory of government, it also initiates a reflexive perspective that takes into account the diverse ways in which the boundaries between the human and the non-human world are negotiated, enacted and stabilized. Furthermore, this theoretical stance makes it possible to analyze the sharp distinction between the natural on the one hand and the social on the other, matter and meaning as a distinctive instrument and effect of governmental rationalities and technologies. 17

![New Configurations in Critical Theory [DOCX 32.01KB]](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/015093857_1-e2b2ee91af2015d5e32b6db76f58dd4d-300x300.png)