bullying and special needs children - Jerome M. Sattler, Publisher, Inc.

advertisement

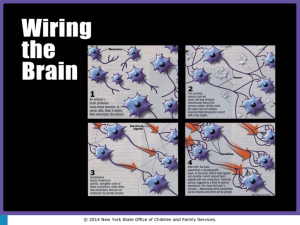

Behavioral Disturbances Including Bullying & Cyberbullying, ASD, ADHD, SLD, and IDD October 24, 2012 JEROME M. SATTLER Department of Psychology San Diego State University Question: Where is the English Channel? Answer: I don’t know. My TV doesn’t pick it up. Question: Please use the word “information” in a sentence. Answer: “During the air show, the Blue Angels flew information.” Question: Use the word “handsome” in a sentence. Answer: “The robber was broke when he went in the bank, so he pointed a pistol at the clerk and said, ‘handsome money over!” Question: Please use the word “stagecoach” in a sentence. Answer: “The stagecoach was so mean that I decided to quit acting class.” Question: What is the chemical formula for water? Answer: H, I, J, K, L, M, N, O. Follow-up question: Tell me about your answer. Answer: “That’s what I learned in school, H to O Commentary on Children [1] “Experience early in life may be especially crucial in organizing the way the basic structures of the brain develop. For example, traumatic experiences at the beginning of life may have more profound effects on the ‘deeper’ structures of the brain, which are responsible for basic regulatory capacities and enable the mind to respond later to stress.” —Daniel Siegel Commentary on Children [2] “Children are ever the future of a society. Every child who does not function at a level commensurate with his or her possibilities, every child who is destined to make fewer contributions to society than society needs, and every child who does not take his or her place as a productive adult diminishes the power of that society's future.” —Degen Horowitz and Marion O’Brien AAIDD Has Issues With DSM-V Proposed Criteria [1] AAIDD = American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities Letter Dated May 16, 2012 from AAIDD to President, American Psychiatric Association The information from the AAIDD letter is quoted verbatim unless otherwise noted. AAIDD Has Issues With DSM-V Proposed Criteria [2] TERMINOLOGY DSM-V uses the term “Intellectual Developmental Disorder” AAIDD uses the term “Intellectual Disability” AAIDD Has Issues With DSM-V Proposed Criteria [3] DEFINITION DSM-V (Criterion A): Intellectual Developmental Disorder (IDD) is a disorder that includes both a current intellectual deficit and a deficit in adaptive functioning with onset during the developmental period. AAIDD Has Issues With DSM-V Proposed Criteria [4] DEFINITION AAIDD: Intellectual disability is characterized by significant limitations both in intellectual functioning and in adaptive behavior as expressed in conceptual, social, and practical adaptive skills. This disability originates before age 18. AAIDD Has Issues With DSM-V Proposed Criteria [5] ARGUMENT AGAINST DSM-V DEFINITION Having the two most authoritative manuals in the country defining “intellectual disability” using different terminology and different definitions would create havoc in the education system, service delivery system, state and federal eligibility determinations, and courts (especially in death penalty cases). AAIDD Has Issues With DSM-V Proposed Criteria [6] DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA DSM-V (Criterion B): Impairment in adaptive functioning for the individual’s age and sociocultural background. Adaptive functioning refers to how well a person meets the standards of personal independence and social responsibility in one or more aspects of daily life activities, AAIDD Has Issues With DSM-V Proposed Criteria [7] DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA (Cont.) DSM-V: such as communication, social participation, functioning at school or at work, or personal independence at home or in community settings. The limitations result in the need for ongoing support at school, work, or independent life. AAIDD Has Issues With DSM-V Proposed Criteria [8] ARGUMENT AGAINST DSM-V CRITERION A AAIDD Recommendation 1: We recommend that Criterion A be modified so that to meet Criterion A, a significant limitation in intellectual functioning is considered to be “approximately” 2 standard deviations below the population mean. AAIDD Has Issues With DSM-V Proposed Criteria [9] ARGUMENT AGAINST DSM-V CRITERION A (Cont.) This level of impairment equates to an IQ score of “about” 70 or less. . . . [We suggest that] a cut-off score of 70 should be considered to represent a range from 65 to 75. AAIDD Has Issues With DSM-V Proposed Criteria [10] ARGUMENT AGAINST DSM-V CRITERION B AAIDD Recommendation 2: We recommend that Criterion B be modified so that to meet Criterion B, a significant limitation in adaptive behavior is defined as deficits of approximately 2 or more standard deviations below the population mean in one or more aspects of adaptive behavior, including: conceptual, social, or practical skills. AAIDD Has Issues With DSM-V Proposed Criteria [11] ARGUMENT AGAINST DSM-V CRITERION B (Cont.) The proposed definition of adaptive behavior as “communication, social participation, functioning at school or at work, or personal independence at home or in community settings” is neither consistent with either the AAIDD position nor with current psychometric literature, and substitutes adaptive functioning for adaptive behaviors. AAIDD Has Issues With DSM-V Proposed Criteria [12] SEVERITY GRID DSM-V suggests a three level severity grid covering three domains: Mild, moderate, and severe for conceptual, social, and practical domains. AAIDD: Eliminate the severity grid. AAIDD Has Issues With DSM-V Proposed Criteria [13] SEVERITY GRID AAIDD Rationale We feel strongly that the proposed DSM-5 severity grid does not reflect or represent best practices in the field of intellectual disability. AAIDD Has Issues With DSM-V Proposed Criteria [14] SEVERITY GRID AAIDD Rationale (Cont.) The grid is problematic for the following reasons: (a) it does not address severity of the disability, but merely provides examples of possible adaptive behavior limitations in conceptual, social, and practical adaptive behavior areas; AAIDD Has Issues With DSM-V Proposed Criteria [15] SEVERITY GRID AAIDD Rationale (Cont.) (b) repeats the error found in the proposed definition of substituting adaptive functioning for adaptive behavior; (c) is internally inconsistent with the proposed APA definition; and (d) represents an old paradigm from the 1980s AAIDD Has Issues With DSM-V Proposed Criteria [16] Sources http://www.aaidd.org/media/Publications/A AIDD%20DSM5%20Comment%20Letter.p df http://www.dsm5.org/proposedrevision/Pa ges/NeurodevelopmentalDisorders.aspx Bullying Generally Involves: Repeated physical, verbal, psychological, sexual, and/or electronic media acts That may threaten, insult, dehumanize, and/or intimidate another individual who cannot properly defend himself or herself Children May Feel Victimized Because of: Size and strength of bully Outnumbered by several bullies Less psychologically resilient than bullies Bullies Attempt to: Control and dominate Use power to subjugate their victims by undermining their worth and status Bullying and Morality Bullying has been described as an immoral action because it humiliates and oppresses innocent victims (Gini, Pozzoli, & Hauser, 2011) Source Gini, G., Pozzoli, T., Borghi, F., & Franzoni, L. (2008). The role of bystanders in students’ perception of bullying and sense of safety. Journal of School Psychology, 46, 617–638. Bullies have adequate moral competence– that is, they have knowledge of right and wrong and an understanding of moral norms But paradoxically they do not have moral compassion–that is, emotional awareness and sensitivity about their moral infractions In fact, bullies may disregard the harmful effects of their actions and blame the victim for causing the bullying behavior Case Example “I was a victim of bullying for two years in gyms. Boys from the football team called me names like ‘lard ass, fat boy, and fag.’ They threw things at me in class and shoved me in the hall. One day they put my head in the toilet and gave me a ‘swirly.’ When I told the gym teacher he told me to ‘toughen up.’ I just stopped going to gym after that.” (Raskauskas & Stotlz, 2007, p. 565) Source Raskauskas, J., & Stoltz, A. D. (2007). Involvement in traditional and electronic bullying among adolescents. Developmental Psychology, 43(3), 564– 575. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.3.564 Case Points Out the Following: Verbal and nonverbal acts of bullying can co-occur School personnel may fail to respond to acts of bullying Examples of Bullying Physical acts such as tripping, shoving, punching, theft, defacing property, and hazing Verbal acts such as name calling, teasing, extortion, and writing insulting graffiti Psychological acts such as rumor spreading, humiliation, and threats of retaliation Sexual acts such as exhibitionism, voyeurism, sexual propositioning, and unwanted physical contact Electronic media acts such as cyberbullying and cyberstalking Cyberbullying Refers to the use of any digital technology device intended to hurt, defame, or embarrass another person Devices include Internet or mobile phones to send or post text or images via text messaging, email, instant messaging, chat rooms, blogs, and social networking websites, such as Facebook and Twitter Cyberstalking Use of any electronic communication to stalk or harass another person in a way that causes substantial emotional distress Cyberstalking includes messages that have threats of harm or that are highly intimidating and make a person afraid about personal safety National Profile of Victims of Bullying, 2008 Children Ages 2 to 17 Physical bullying: 13.2% Males: 16.7% Females: 12.8% Emotional bullying: 19.7% Males: 20.6% Females: 23.5% Internet harassment: 5.6% Ages 14 to 17 years Source: Finkelhor, D., Turner, H., Ormrod, R., Hamby, S., & Kracke, K. (2009). Children’s exposure to violence: A comprehensive national survey. Retrieved from http://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/ojjdp/227744 .pdf National Profile of LGBT Victims of Bullying, 2009 Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender 84% reported being verbally harassed 40% reported being physically harassed 19% reported being physically assaulted 72% often heard homophobic remarks (such as "faggot" or "dyke") LGBT (Cont.) 61% reported feeling unsafe in school because of their sexual orientation 29% missed at least one day of school in the past month because of safety concerns compared to about 8% of a national sample LGBT (Cont.) GPA was almost half a grade lower of students who were frequently harassed than other students (2.7 vs. 3.1) Increased levels of victimization were related to increased levels of depression and anxiety and decreased levels of selfesteem Source: Presgraves, D. (2010). 2009 National School Climate Survey: Nearly 9 out of 10 LGBT students experience harassment in school. Retrieved from http://www.glsen.org/cgibin/iowa/all/news/record/2624.html Which Children Become Victims of Bullying? Children who are LGB T Children with medical, intellectual, learning, and/or psychological disabilities Characteristics of children that may draw attention include: Overweight or underweight Physical disabilities (Cerebral Palsy) Reading problems (Learning Disability) Characteristics of children that may draw attention include: (Cont.) Speech and communication problems (Stuttering) Hyperactivity (ADHD) Ritualistic behaviors (Autism Spectrum Disorders) Characteristics of children that may draw attention include: (Cont.) Use of special devices (visually, hearing, or physically impaired) Dress differently (cultural or religious practices) Characteristics of children that may draw attention include: (Cont.) Different skin color Low self-esteem Appear weak Signs of Bullying in Victims Physical Signs—Child… Has unexplained bruises, scratches, cuts, and/or torn clothes Brings to school damaged possessions or reports them ‘lost’ Complains of tiredness and fatigue Complains of illness (nonspecific pains or headaches) Has loss of appetite, sleep difficulties, and/or wets bed Behavioral Signs—Child… Takes an “illogical” walking route to and from school Shows little interest in school work Has deteriorating school performance Stays late at school in order to avoid encounters with other students Displays “victim” body language (hangs head, hunches shoulders, and/or avoids eye contact) Emotional Signs—Child … Feels picked on or persecuted Feels isolated, lonely, and rejected Withdraws socially and/or feels ashamed Has poor concentration, cries easily, has angry outbursts, and/or displays mood swings Talks about hopelessness Talks about committing suicide Signs of Cyberbullying Distress—Child… Is upset after being online Is upset after seeing text messages Stops using the computer, cell phone, and/or smartphone unexpectedly Shows any of the physical, behavioral, and/or emotional signs presented for bullying in general Characteristics of Student Bullies Aggressive and dominant Impulsive, prone to losing temper, and outbursts of anger Devious and manipulative Spiteful, selfish, mean, and/or unpleasant Insincere, insecure, and/or immature Poor social skills Average popularity Desire to increase their social status Want to climb school social ladder Have limited empathy for their victims As adults may: Continue their aggressive behavior Engage in child abuse or domestic violence Tend to remain bullies unless they receive counseling Why are Victims Reluctant to Report Bullying? Fear retaliation Feel shame at being a victim Fear would not be believed Fear parents would worry Don’t think anything would change Think advice of parents or teachers would make problem worse Fear teacher would tell the bully who told on him or her Don’t want to be thought of as a snitch Why are Bystanders Reluctant to Report Bullying? They know that bullying is wrong but . . . Don’t want to raise the bully’s wrath and become the next target Don’t want to be thought of as a snitch and be rejected by their peers May wrongly believe that they are not responsible for stopping the bullying May think that bullying is acceptable May assume that school personnel don’t care enough to stop the bullying May feel unsafe in the classroom and on the playground May worry about becoming the next victim May feel powerless to report bullying May feel guilty for not reporting it May have heightened anxiety, depression, and/or substance abuse May become bullies themselves because they think that this is a way to become part of a group May think that bullying is not so bad because sometimes adults don’t seem to care about who is bullied Why do Some Bystanders Intervene? Are victim’s friends Believe that their parents expect them to support victims Believe that it is the moral and proper thing to do Believe that their peer group supports their actions Differences Between Bullying and Cyberbulling Bullying Victim can hide from bully when at home Event is discrete Audience is limited Bully is present and not anonymous Bully can see suffering of victim Bully has opportunities for empathy and remorse Bullying (Cont.) Bystanders can intervene Bully may gain status by showing abusive power Cyberbullying Victim cannot hide from bully when at home Event can be continuous Audience is potentially very large Bully is invisible and may be anonymous Bully cannot see suffering of victim Bully has few opportunities for empathy and remorse Cyberbullying (Cont.) Bystanders have little opportunity to intervene Bully lacks opportunity to show his or her abusive power immediately Shaniya Boyd A Child with Special Needs Shaniya is 8 years old and has cerebral palsy. She tried to jump out of a window at school and told her mother that she just wanted to get away. Shaniya had been teased, kicked in the forehead, and knocked off her crutches. The bullying had been going on for some time and the school did little to stop it. Shaniya was put in a special class, but the bullying still happened in the hallway, cafeteria, or outside during play time. Mrs Boyd said, “They still managed to get their hands on my child.” Source: Abilitypath.org. (n.d.). Walk a mile in their shoes: Bullying and the child with special needs. Retrieved from http://www.abilitypath.org/areas-ofdevelopment/learning-schools/bullying/articles/walk-a-mile-intheir-shoes.pdf Children with Special Needs Children with special needs may have: Limited social network and few friends Difficulty describing their victimization Difficulty distinguishing good-natured kidding from bullying Difficulty understanding nuances and jokes, which they may interpret as bullying Children with special needs may also act as bullies if they: Want to protect themselves from further victimization Learn bullying behavior in other social settings Feel extremely anxious Cannot size up a situation realistically Have limited frustration tolerance Children with special needs may also act as bullies if they: (Cont.) Feel they are being pushed too far Feel their resources are exhausted Fail to realize that their “playful” behavior can hurt others Bullying may have harmful effects on children with special needs: Limit motivation to achieve Increase anxiety about academic performance Interfere with their use of assistive technology Lower their grades Bullying may have harmful effects on children with special needs: (Cont.) Interfere with their compliance with treatment regimens Increase frequency and strength of their symptoms Helping Victims of Bullying Help them develop: Problem solving skills Conflict resolution skills Emotional regulation skills, including how to handle anxiety, depression and anger Help them develop: (Cont.) Assertiveness skills Self-adequacy skills Ability to say “no” or “stop that” Ability to know when to go to a safe room when under severe stress Helping Bullies Change habitual patterns of thought and action that support bullying: Develop new skills Challenge old beliefs Replace impulsive with reflective decision-making Helping children who are bullies: Develop anger management skills Develop empathy skills Recognize that they can engage in responsible and moral behavior Appreciate the harm they cause their victims Give up self-justifying mechanisms, egocentric reasoning, and distortions in morality Effective Strategies To Counter Bullying In Schools Designing comprehensive intervention strategies involving students, teachers, administrators, families, and communities Building bullying prevention programs based on principles of science and supported by scientifically valid evidence of effectiveness Applying school discipline rules, policies, and sanctions fairly and consistently Implementing policies at all levels, including primary, junior, intermediate, and high school Motivating students, teachers, administrators, and parents to understand that: Bullying is a serious and preventable problem Antibullying programs must be given a chance to work They themselves can make a difference Presenting strategies that are clear, relevant, and comprehensible to both teachers and students Encouraging bystanders to report bullying Partnering with law enforcement and mental health agencies to identify and address serious cases of bullying Assessing the frequency of bullying, the effectiveness of the intervention program, and making adjustments as needed (see Delaware Attorney General, n.d.; Hamburger et al., 2011; Safe School Survey, 2003) Sources Delaware Attorney General. (n.d.). Bully Worksheet Questionnaire. Retrieved from http://attorneygeneral.delaware.gov/school s/bullquesti.shtml Sources Hamburger, M. E., Basile, K. C., Vivolo, A. M. (2011). Measuring bullying victimization, perpetration, and bystander experiences: A compendium of assessment tools. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/Bu llyCompendiumBk-a.pdf Sources Safe School Survey. (2003). Safe School Survey sample menu. Retrieved from https://sdfs.esc18.net/Sample_Surveys/SS M.asp 10 Tips for Parents 1. 2. 3. Talk often with your child, listen carefully, and note any changes in your child’s behavior, especially signs of anxiety Talk about what bullying and cyberbullying means. See such websites as www.stopbullying.gov and www.stopbullyingnow.com Encourage your child to tell you when he or she is being bullied and discourage your child from bullying others 4. 5. 6. Encourage your child to tell a member of the school staff if the bullying took place at school Tell your child to refuse to join in if he or she sees another child being bullied and offer support to the child who is being bullied Tell your child to learn about the school’s rules and sanctions regarding bullying and cyberbullying 7. 8. Remind your child that real people with real feelings are behind screen names and profiles Discuss with your child why it is a good idea to post only information that he or she is comfortable with others seeing and to never share passwords with anyone except you and another close family member Tell your child to take Internet harassment seriously because it is harmful and unacceptable 10. Tell your child that you may review his or her online communications if you think there is reason for concern about his or her safety 9. 10 Tips for Teachers 1. 2. 3. Explain to students the difference between playfulness and bullying or cruelty Let students know that bullying is unacceptable and against school rules Tell students, whether they are victims or bystanders, to report bullying or cyberbullying immediately to a member of the school staff 4. 5. 6. Emphasize the difference between tattling and telling on someone who is bullying another student Identify and intervene upon undesirable attitudes and behaviors that could be “gateway behaviors” to bullying and cyberbullying Watch for signs of bullying and cyberbullying and stop either one immediately Listen receptively to parents who report bullying and/or cyberbullying 8. Report all incidents of bullying and cyberbullying to the school administration 9. Always respond to requests of help from victims and make sure that they know that being bullied is not their fault and that it is OK to feel scared or upset 10. Closely monitor students’ use of computers at school and become familiar with cyberbullying, its dangers 7. State Laws Against Bullying 45 states have passed anti-bullying laws designed to protect students from being harassed, threatened, or humiliated Other states may be considering similar legislation Seth’s Law (AB9) An Anti-Bullying Law Governor Jerry Brown signed “Seth’s Law” on October 9, 2011 Named for 13-year-old Seth Walsh, who killed himself in 2010 after years of antigay bullying. Seth was routinely verbally harassed for his nonconforming appearance Was touched inappropriately by other students Had food and water containers thrown at him Was made the subject of rumors and verbal assaults regarding his sexuality Bullying became so bad that he ceased changing in the locker room as he feared for his own safety Requirements of Seth’s Law Schools must: Implement anti-harassment and antidiscrimination policies and programs directed toward sexual orientation and gender identity and expression, race, ethnicity, nationality, disability, and religion Schools must: (Cont.) Give parents clearer knowledge of: What to expect from school administrators when they are handling instances of bullying Ways parents can report their concerns if they think school administrators are not acting appropriately Put bullying complaint forms on schools’ websites Schools must: (Cont.) Post schools’ anti-bullying policies in visible places on school grounds Investigate and resolve bullying complaints within a set period of time Source: Williams (2011) Source Williams, S. (2011). Anti-bullying ‘Seth’s law’ passes California senate. Retrieved from http://www.care2.com/causes/antibullying-seths-law-passes-californiasenate.html State Laws Generally Require Schools To Have anti-bullying policies that also address cyberbullying Investigate reports of bullying Provide counseling to bullies and their victims Report incidents of bullying to parents and law enforcement Take action even if the bullying occurs off campus, through the Internet, or other telecommunications methods Comment on State Laws: Who will train teachers and administrators? How will the new curriculum be added to the existing curriculum? Developing a cyberbullying policy for schools is not easy Laws must balance individuals’ protection against their free-speech rights This issue came up in the famous case of United States v. Drew, 2008 United States v. Drew, 2008 Meier, a 13-year-old girl from Missouri, hanged herself after being harassed online by Lori Drew, a 49-year-old middle-aged woman United States v. Drew, 2008 (Cont.) After courting Meier by posing as a 16-year-old boy on a social networking site and gaining her trust, Drew sent insulting, hurtful messages to Meier, who had a history of depression and low self-esteem, at one point telling her that the world would be better without her in it Drew was prosecuted under the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act United States v. Drew, 2008 (Cont.) The judge acquitted Drew because he found that the language in the Act was written so broadly that, were she to be found guilty for creating this fictitious profile, many other relatively innocent Internet users who were in violation of similar terms of agreement could be prosecuted for relatively minor offenses D.C. et al. v. R.R. et al., 2010 However, in another case, the court ruled that free speech is not unlimited 2nd District Court of Appeal of California ruled that the 1st Amendment does not protect Internet banter among teenagers if a message contains genuine threats of harm D.C. et al. v. R.R. et al., 2010 (Cont.) The threats in this case included the posting of death threats and anti-gay diatribes against D.C. on his website The threatening and insulting messages included saying that: The classmates wanted to “pound your head in with an ice pick” D.C. was “wanted dead or alive” D.C. et al. v. R.R. et al., 2010 (Cont.) Appeals court concluded that: “The students who posted the threats sought to destroy D.C.'s life, threatened to murder him, and wanted to drive him out of Harvard-Westlake and the community in which he lived” (p. 3) Concluding Comment John Palfrey (2010), a professor of law at Harvard Law School, pointed out that “No one federal law will prevent tragedies from happening. Most of the time, we have the laws on the books that we need. It’s a commitment to teaching and mentoring, to being supportive and to being tough where we have to be, that can help.” Source Palfrey, J. (2010). Solutions beyond the law. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/roomfordebate/20 10/09/30/cyberbullying-and-a-studentssuicide/palfrey Features of a Positive School Climate [1] Fosters feelings of belonging Promotes the self-worth and dignity of each student Inspires efforts for self-improvement Maximizes opportunities for the full realization of each student’s potential Features of a Positive School Climate [2] Promotes self-determination, social responsibility, and empowerment among all students Develops, promotes, and reinforces nonstigmatizing language Disavows and sanctions antidemocratic policies and practices, especially repression and discrimination Features of a Positive School Climate [3] Encourages diversity and emphasizes its strengths, assets, and opportunities Rejects and prevents the isolation and marginalization of individuals and groups Provides regular occasions for positive interactions for all students Features of a Positive School Climate [4] Communicates routinely high expectations for everyone in the school community Promotes cooperative learning, mutual responsibility, social competency, and democratic participation in decision making Shows awareness of the mental health needs of students and staff and provides adequate mental health services Features of a Positive School Climate [5] Promotes norms of caring and concern for the dignity and worth of every student in a safe, secure school environment Provides conflict resolution leaders and mechanisms Features of a Positive School Climate [6] Source: Lawson, H. A., Quinn, K. P., Hardiman, E., & Miller, R. L., Jr. (2006). Mental health needs and problems as opportunities for expanding the boundaries of school improvement. In R. J. Waller (Ed.), Fostering child & adolescent mental health in the classroom (pp. 293–309). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)[1] DSM-V, Revised January 26, 2011 Definition: Autism spectrum disorder is a neurodevelopmental disorder and must be present from infancy or early childhood, but may not be detected until later because of minimal social demands and support from parents or caregivers in early years. Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)[2] Neural development comprises the processes that generate, shape, and reshape the nervous system, from the earliest stages of embryogenesis to the final years of life. Defects in neural development can lead to cognitive, motor, and intellectual disability, as well as neurological disorders such as autism and intellectual disability. Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)[3] Diagnostic Criteria Must meet criteria A, B, C, and D: Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)[4] Diagnostic Criteria A Persistent deficits in social communication and social interaction across contexts, not accounted for by general developmental delays, and manifest by all 3 of the following: Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)[5] Diagnostic Criteria A 1. Deficits in social-emotional reciprocity ranging from abnormal social approach and failure of normal back and forth conversation through reduced sharing of interests, emotions, and affect and response to total lack of initiation of social interaction, Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)[6] Diagnostic Criteria A 2. Deficits in nonverbal communicative behaviors used for social interaction; ranging from poorly integrated- verbal and nonverbal communication, through abnormalities in eye contact and bodylanguage, or deficits in understanding and use of nonverbal communication, to total lack of facial expression or gestures. Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)[7] Diagnostic Criteria A 3. Deficits in developing and maintaining relationships, appropriate to developmental level (beyond those with caregivers); ranging from difficulties adjusting behavior to suit different social contexts through difficulties in sharing imaginative play and in making friends to an apparent absence of interest in people Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)[8] Diagnostic Criteria B Restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, or activities as manifested by at least two of the following: Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)[9] Diagnostic Criteria B 1. Stereotyped or repetitive speech, motor movements, or use of objects; (such as simple motor stereotypies, echolalia, repetitive use of objects, or idiosyncratic phrases). Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)[10] Diagnostic Criteria B 2. Excessive adherence to routines, ritualized patterns of verbal or nonverbal behavior, or excessive resistance to change; (such as motoric rituals, insistence on same route or food, repetitive questioning or extreme distress at small changes). Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)[11] Diagnostic Criteria B 3. Highly restricted, fixated interests that are abnormal in intensity or focus; (such as strong attachment to or preoccupation with unusual objects, excessively circumscribed or perseverative interests). Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)[12] Diagnostic Criteria B 4. Hyper-or hypo-reactivity to sensory input or unusual interest in sensory aspects of environment; (such as apparent indifference to pain/heat/cold, adverse response to specific sounds or textures, excessive smelling or touching of objects, fascination with lights or spinning objects). Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)[13] Diagnostic Criteria C Symptoms must be present in early childhood (but may not become fully manifest until social demands exceed limited capacities) Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)[14] Diagnostic Criteria D Symptoms together limit and impair everyday functioning Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)[15] Severity Level for ASD Level 3 Level 2 Level 1 Requiring very substantial support Requiring substantial support Requiring support Social Communication Social Communication Social Communication RRB RRB RRB Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)[16] Severity Level for ASD Level 3: Requiring very substantial support Social Communication Severe deficits in verbal and nonverbal social communication skills cause severe impairments in functioning; very limited initiation of social interactions and minimal response to social overtures from others. Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)[17] Severity Level for ASD (Level 3) Restricted Interests & Repetitive Behaviors (RRB) Preoccupations, fixated rituals and/or repetitive behaviors markedly interfere with functioning in all spheres. Marked distress when rituals or routines are interrupted; very difficult to redirect from fixated interest or returns to it quickly Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)[18] Severity Level for ASD Level 2: Requiring substantial support Social Communication Marked deficits in verbal and nonverbal social communication skills; social impairments apparent even with supports in place; limited initiation of social interactions and reduced or abnormal response to social overtures from others Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)[19] Severity Level for ASD (Level 2) Restricted Interests & Repetitive Behaviors (RRB) RRBs and/or preoccupations or fixated interests appear frequently enough to be obvious to the casual observer and interfere with functioning in a variety of contexts. Distress or frustration is apparent when RRB’s are interrupted; difficult to redirect from fixated interest Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)[20] Severity Level for ASD Level 1: Requiring support Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)[21] Severity Level for ASD (Level 1) Social Communication Without supports in place, deficits in social communication cause noticeable impairments. Has difficulty initiating social interactions and demonstrates clear examples of atypical or unsuccessful responses to social overtures of others. May appear to have decreased interest in social interactions Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)[22] Severity Level for ASD (Level 1) Restricted Interests & Repetitive Behaviors (RRB) Rituals and repetitive behaviors (RRB’s) cause significant interference with functioning in one or more contexts. Resists attempts by others to interrupt RRB’s or to be redirected from fixated interest Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)[23] Deleted from DSM-V Asperger’s Disorder Childhood disintergrative disorder Pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified Associated Features of ASD [1] 1. Regression in development Gradual or rapid backward movement in their development. Regression occurs in approximately 15% to 50% of children with autism spectrum disorder, Most commonly at approximately 18 months of age Associated Features of ASD [2] 2. Difficulties in eating or sleeping: “Picky eaters”—Feeding problems occur in approximately 46% to 89% of children with autism spectrum disorder Approximatley 40% to 80% of children with autism spectrum disorder also demonstrate sleep problems Associated Features of ASD [3] 3. Aggressive behavior Display aggressive behavior toward themselves (self-injurious behavior) or toward other people Associated Features of ASD [4] 3. Aggressive behavior (Cont.) Examples of self-injurious behaviors include Head banging Hair pulling Self-scratching Self-biting Associated Features of ASD [5] 3. Aggressive behavior (Cont.) Explanation for self-injurious behavior: In response to frustration (e.g., when a child is unable to communicate) Or as a form of self-stimulation Associated Features of ASD [6] 3. Aggressive behavior (Cont.) Ranges from relatively mild (e.g., scratching the skin) to life threatening (e.g., repeated head-banging) Incidence of self-injurious behavior ranges from 20% to 71% Associated Features of ASD [7] 3. Aggressive behavior (Cont.) Higher levels of self-injury associated with children who Are also intellectually disabled With those who have severely impaired communication, socialization, and daily living skills Associated Features of ASD [8] 4. “Savant Skills” May have special skills or what has been termed “savant skill.” Examples include: Ability to draw incredibly accurate and detailed perspective drawings Having perfect pitch Associated Features of ASD [9] 4. “Savant Skills” (Cont.) Examples include: Being able to state the day of the week for a date far in the future Being able to play a piano concerto after hearing it once Being able to calculate extremely difficult mathematical equations without a calculator Associated Features of ASD [10] 4. “Savant Skills” These abilities may not be used functionally. Example: An adolescent who is able to calculate difficult mathematical equations without a calculator may not be able to calculate the correct change when purchasing items Assessment Techniques for ASD [1] Case history review, including medical evaluation Educational history review Interview Observation Autism Diagnostic Interview–Revised (ADI–R) WISC–IV Assessment Techniques for ASD [2] SB5 DAS–II Mullen Scales of Early Learning Bayley Scales of Infant Development– Third Edition (Bayley-III) Merrill-Palmer-Revised (M-P-R) Leiter International Performance Scale– Revised (Leiter–R) Assessment Techniques for ASD [3] Universal Nonverbal Intelligence Test (UNIT) Receptive Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test–Fourth Edition (PPVT–IV) Listening Comprehension Scale of the Oral and Written Language Scales (OWLS) Comprehensive Assessment of Spoken Language (CASL) Assessment Techniques for ASD [4] Bracken Basic Concept Scale–Revised (BBCS–R) Peabody Individual Achievement Test– Revised Normative Update (PIAT–R/NU) Group achievement tests Hearing tests, visual, medical examinations, and genetic testing may also be recommended Observation Before Testing [1] Observe the child in his or her classroom, playground, or home. Consider the following: Does the child make eye contact? Does the child point or gesture to indicate a response? Does the child use signs, words, phrases, or sentences? Observation Before Testing [2] Does the child use an augmentative or alternative communication system (AAC), such as a speech-generating device or a picture system to communicate (e.g., pointing to pictures instead of using words). Does the child understand gestures or signing? Observation Before Testing [3] Does the child follow simple verbal directions? Does the child have sufficient attention to do the class assignment? Co-Occurring Disorders with ASD[1] Estimated prevalence rates of cooccurrence of autism spectrum disorder with other disorders are difficult to establish, but here is what we know: Intellectual disability (40% to 69%) Depression (4% to 58%) Anxiety disorders (7% to 84%) Tic disorders (30%) Co-Occurring Disorders with ASD[2] Seizure disorders (11% to 39%) Fragile-X syndrome (2% to 6%) Gastrointestinal problems (9% to 70%) One or more other psychiatric conditions (up to 70%) Two or more other psychiatric disorders (up to 41%) WISC–IV and High Functioning Children with Autism [1] Mayes & Calhoun (2007) N = 54 Ages 6 to 14 yrs., M = 8.2 yrs. FSIQ = 101 GAI = 113 VC =107 PR = 115 WM = 89 PS = 85 WISC–IV and High Functioning Children with Autism [2] Correlations between the WIAT–II and WISC–IV (Mayes & Calhoun, 2007) FSIQ Word Reading = .64 Reading Comprehension = .68 Numerical Operations = .80 Written Expression = .75 GAI .60 .64 .78 .68 WISC–IV and High Functioning Children with Autism [3] SOURCE Mayes, S. D., & Calhoun, S. L. (2007). Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children– Third and –Fourth Edition predictors of academic achievement in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. School Psychology Quarterly, Vol 22(2), 234–249. doi: 10.1037/10453830.22.2.234 Interventions for ASD [1] Characteristics of Early Intervention Programs Intensive intervention (at least 25 hours per week) in a highly motivating environment with measurable educational objectives as soon as an autism spectrum disorder is suspected Interventions for ASD [2] Characteristics of Early Intervention Programs (Cont.) A curriculum focused on attention and compliance, joint attention, motor and behavioral imitation, communication, reciprocal interaction (e.g., responding to the behavior of others), appropriate use of toys, and self-management of behavior Interventions for ASD [3] Characteristics of Early Intervention Programs (Cont.) Highly structured teaching environments with visual schedules and clear physical boundaries and with low student-to-staff ratios Systematic strategies for generalizing newly acquired skills to a wide range of situations Interventions for ASD [4] Characteristics of Early Intervention Programs (Cont.) Maintenance of predictability and routine in daily schedules Promotion of social interaction A functional approach to problem behaviors (e.g., replacing the functions served by negative behaviors with positive behaviors) Interventions for ASD [5] Characteristics of Early Intervention Programs (Cont.) A focus on skills needed for successful transition from an early intervention program to the skills needed for regular preschool and kindergarten classrooms A high level of family involvement, including parental training, where appropriate Interventions for ASD [6] Characteristics of Early Intervention Programs (Cont.) Progress regularly evaluated and objectives regularly adjusted based on ongoing assessment of skills Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (AD/HD)[1] DSM-V, Revised May 1, 2012 Definition: AD/HD consists of a pattern of behavior that is present in multiple settings where it gives rise to social, educational or work performance difficulties. Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (AD/HD)[2] Diagnostic Criteria Must meet criteria A1 or A2, B, C, and D: Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (AD/HD)[3] Diagnostic Criteria A Either (A1) and/or (A2). A1. Inattention: Six (or more) of the following symptoms have persisted for at least 6 months to a degree that is inconsistent with developmental level and that impact directly on social and academic/occupational activities. Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (AD/HD)[4] Diagnostic Criteria A1 a. Often fails to give close attention to details or makes careless mistakes in schoolwork, at work, or during other activities (e.g., overlooks or misses details, work is inaccurate). Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (AD/HD)[5] Diagnostic Criteria A1 b. Often has difficulty sustaining attention in tasks or play activities (e.g., has difficulty remaining focused during lectures, conversations, or reading lengthy writings). c. Often does not seem to listen when spoken to directly (e.g., mind seems elsewhere, even in the absence of any obvious distraction). Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (AD/HD)[6] Diagnostic Criteria A1 d. Often does not follow through on instructions and fails to finish schoolwork, chores, or duties in the workplace (e.g., starts tasks but quickly loses focus and is easily sidetracked; fails to finish schoolwork, household chores, or tasks in the workplace). Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (AD/HD)[7] Diagnostic Criteria A1 e. Often has difficulty organizing tasks and activities (e.g., difficulty managing sequential tasks; difficulty keeping materials and belongings in order; messy, disorganized, work; poor time management; tends to fail to meet deadlines). Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (AD/HD)[8] Diagnostic Criteria A1 f. Often avoids, dislikes, or is reluctant to engage in tasks that require sustained mental effort (e.g., schoolwork or homework; for older adolescents and adults, preparing reports, completing forms, or reviewing lengthy papers). Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (AD/HD)[9] Diagnostic Criteria A1 g. Often loses things necessary for tasks or activities (e.g., school materials, pencils, books, tools, wallets, keys, paperwork, eyeglasses, or mobile telephones). h. Is often easily distracted by extraneous stimuli (for older adolescents and adults, may include unrelated thoughts). Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (AD/HD)[10] Diagnostic Criteria A1 i. Is often forgetful in daily activities (e.g., chores, running errands; for older adolescents and adults, returning calls, paying bills, keeping appointments). Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (AD/HD)[11] Diagnostic Criteria A2 A2. Hyperactivity and Impulsivity: Six (or more) of the following symptoms have persisted for at least 6 months to a degree that is inconsistent with developmental level and that impact directly on social and academic/occupational activities. Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (AD/HD)[12] Diagnostic Criteria A2 a. Often fidgets with or taps hands or feet or squirms in seat. b. Often leaves seat in situations when remaining seated is expected (e.g., leaves his or her place in the classroom, office or other workplace, or in other situations that require remaining seated). Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (AD/HD)[13] Diagnostic Criteria A2 c. Often runs about or climbs in situations where it is inappropriate. (In adolescents or adults, may be limited to feeling restless). d. Often unable to play or engage in leisure activities quietly. Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (AD/HD)[14] Diagnostic Criteria A2 e. Is often “on the go,” acting as if “driven by a motor” (e.g., is unable or uncomfortable being still for an extended time, as in restaurants, meetings, etc; may be experienced by others as being restless and difficult to keep up with). f. Often talks excessively. Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (AD/HD)[15] Diagnostic Criteria A2 g. Often blurts out an answer before a question has been completed (e.g., completes people’s sentences and “jumps the gun” in conversations, cannot wait for next turn in conversation). h. Often has difficulty waiting his or her turn (e.g., while waiting in line). Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (AD/HD)[16] Diagnostic Criteria A2 i. Often interrupts or intrudes on others (e.g., butts into conversations, games, or activities; may start using other people’s things without asking or receiving permission, adolescents or adults may intrude into or take over what others are doing). Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (AD/HD)[17] Diagnostic Criteria B Several inattentive or hyperactive-impulsive symptoms were present prior to age 12. Diagnostic Criteria C Criteria for the disorder are met in two or more settings (e.g., at home, school or work, with friends or relatives, or in other activities). Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (AD/HD)[18] Diagnostic Criteria D There must be clear evidence that the symptoms interfere with or reduce the quality of social, academic, or occupational functioning. Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (AD/HD)[19] Diagnostic Criteria E The symptoms do not occur exclusively during the course of schizophrenia or another psychotic disorder and are not better accounted for by another mental disorder (e.g., mood disorder, anxiety disorder, dissociative disorder, or a personality disorder). Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (AD/HD)[20] Combined Presentation: If both Criterion A1 (Inattention) and Criterion A2 (Hyperactivity-Impulsivity) are met for the past 6 months. Predominantly Inattentive Presentation: If Criterion A1 (Inattention) is met but Criterion A2 (Hyperactivity-Impulsivity) is not met and 3 or more symptoms from Criterion A2 have been present for the past 6 months. Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (AD/HD)[21] Inattentive Presentation (Restrictive): If Criterion A1 (Inattention) is met but no more than 2 symptoms from Criterion A2 (Hyperactivity-Impulsivity) have been present for the past 6 months. Predominantly Hyperactive/Impulsive Presentation: If Criterion A2 (Hyperactivity-Impulsivity) is met and Criterion A1 (Inattention) is not met for the past 6 months. Other Problems in Children with ADHD [1] COGNITIVE DEFICITS Deficits in executive functions Mild deficits in intelligence test scores Learning disabilities Memory difficulties Impaired behavioral and verbal creativity Other Problems in Children with ADHD [2] SOCIAL AND ADAPTIVE FUNCTIONING DEFICITS Difficulties with social and adaptive functioning Difficulties adhering to rules and instructions Difficulties in regulating the pace of their actions, including being able to slow down or speed up as needed Other Problems in Children with ADHD [3] MOTIVATIONAL AND EMOTIONAL DEFICITS Motivation difficulties Limited persistence Emotional reactivity Other Problems in Children with ADHD [4] MOTOR, PHYSICAL, AND HEALTH DEFICITS Poor fine-motor and gross-motor coordination Minor physical anomalies Difficulties regulating sleep and alertness General health problems and possible delay in growth during childhood Proneness to accidental injuries ADHD and Organophosphate Pesticides [1] Sample:1,139 children representative of US population; 119 met ADHD criteria Results: These children were 1.55 times more likely than others to have high concentrations of urinary dimethyl alkylphosphate, an organophosphate Conclusion: organophosphate exposure, at levels common among US children, may contribute to ADHD prevalence. ADHD and Organophosphate Pesticides [2] SOURCE Bouchard, M. F., Bellinger, D. C., Wright, R. O. & Weisskopf, M. G. (2010). Attentiondeficit/hyperactivity disorder and urinary metabolites of organophosphate pesticides. Pediatrics,125(6), e1270– e1277. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-3058 ADHD and Organophosphate Pesticides [3] Purpose: Is maternal urinary dialkyl phosphate metabolites, an organophosphate, associated with ADHD? Sample: Mexican-American children living in Salinas Valley, CA Followed to ages 3½ (N = 331) and 5 (N = 323) years Findings and conclusion: Maternal urinary dialkyl phosphate metabolites are associated with ADHD, especially at age 5 years ADHD and Organophosphate Pesticides [4] SOURCE Marks, A. R., Harley, K., Bradman, A., Kogut, K., Barr, D. B., Johnson, C., Calderon, N., & Eskenazi, B. (2010). Organophosphate pesticide exposure and attention in young Mexican-American children. Environmental Health Perspectives. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1002056 ADHD WISC–IV and ADHD [1] McConaughy, Ivanova, Antshel, & Eiraldi (2009) ADHD Control N = 74 26 Ages 6 to 11 yrs FSIQ = 96 113 VCI = 97 112 PRI = 99 113 WMI = 96 109 PSI = 93 103 WISC-IV and ADHD [2] SOURCE McConaughy, S. H., Ivanova, M. Y., Antshel, K., & Eiraldi, R. B. (2009). Standardized observational assessment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder combined and predominantly inattentive subtypes. I. Test session observations. School Psychology Review, Vol 38(1), 45–66. Long-Term Effects of ADHD— Research Study Introduction About 5.4 million children are diagnosed with ADHD in the U.S. 3% to 7% of school-aged children are currently struggling with ADHD How does ADHD affects their adult lives? Long-Term Effects of ADHD— Research Study Introduction (Cont.) 33-year follow-up study of 135 middleaged men with childhood ADHD without conduct disorders Men were in their forties at follow-up Long-Term Effects of ADHD— Research Study Results in Comparison with Control Group About 2.5 years fewer years of education 3.7% had higher degrees compared to nearly 30% of the control group Majority (84%) were holding jobs, but at significantly lower positions than peers without ADHD Long-Term Effects of ADHD— Research Study Results in Comparison with Control Group (Cont.) ADHD group earned $40,000 less in salary than their unaffected counterparts Higher divorce rates (22% vs 5%) More antisocial personality disorders (16% vs 0%) More substance abuse (14% vs 5%) Long-Term Effects of ADHD— Research Study Results in Comparison with Control Group (Cont.) Higher rate of psychiatric hospitalizations (24% vs 7%) Higher rate of incarcerations (36% vs 12%) Did not have higher rates of mood and anxiety disorders, like depression Long-Term Effects of ADHD— Research Study Suggested Interventions Children with ADHD need academic support in school Need help in overcoming their frustrations and challenges in paying attention and retaining what they learn Need emotional support from the family Long-Term Effects of ADHD— Research Study Suggested Interventions (Cont.) Need help in developing coping skills needed to meet their adult challenges in the workplace, in relationships, and in social interactions. Long-Term Effects of ADHD— Research Study Source Klein, R. G., Mannuzza, S., Olazagasti, M. A., Roizen, E., Hutchison, J. E., Lashua, E. C., & Castellanos, F. X. (2012). Clinical and functional outcome of childhood attentiondeficit/hyperactivity disorder 33 years later. Archives of General Psychiatry. Advanced online publication. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2012.271 Specific Learning Disorder (SLD)[1] DSM-V, Revised May 1, 2012 Definition: A diagnosis of Specific Learning Disorder is made by a clinical synthesis of the individual’s history (development, medical, family, education), psycho-educational reports of test scores and observations, and response to intervention, using the following diagnostic criteria. Specific Learning Disorder (SLD)[2] Diagnostic Criteria Must meet criteria A, B, C, and D: Specific Learning Disorder (SLD)[3] Diagnostic Criteria A History or current presentation of persistent difficulties in the acquisition of reading, writing, arithmetic, or mathematical reasoning skills during the formal years of schooling (i.e., during the developmental period). The individual must have at least one of the following: Specific Learning Disorder (SLD)[4] Diagnostic Criteria A 1. Inaccurate or slow and effortful word reading 2. Difficulty understanding the meaning of what is read (e.g., may read text accurately but not understand the sequence, relationships, inferences, or deeper meanings of what is read Specific Learning Disorder (SLD)[5] Diagnostic Criteria A 3. Poor spelling (e.g., may add, omit, or substitute vowels or consonants) 4. Poor written expression (e.g., makes multiple grammatical or punctuation errors within sentences, written expression of ideas lack clarity, poor paragraph organization, or excessively poor handwriting) Specific Learning Disorder (SLD)[6] Diagnostic Criteria A 5. Difficulties remembering number facts 6. Inaccurate or slow arithmetic calculation 7. Ineffective or inaccurate mathematical reasoning. 8. Avoidance of activities requiring reading, spelling, writing, or arithmetic Specific Learning Disorder (SLD)[7] Diagnostic Criteria B Current skills in one or more of these academic skills are well-below the average range for the individual’s age or intelligence, cultural group or language group, gender, or level of education, as indicated by scores on individually-administered, standardized, culturally and linguistically appropriate tests of academic achievement in reading, writing, or mathematics. Specific Learning Disorder (SLD)[8] Diagnostic Criteria C The learning difficulties are not better explained by Intellectual Developmental Disorder, Global Developmental Delay, neurological, sensory (vision, hearing), or motor disorders. Specific Learning Disorder (SLD)[9] Diagnostic Criteria D Learning difficulties identified in Criterion A (in the absence of the tools, supports, or services that have been provided to enable the individual compensate for these difficulties) significantly interfere with academic achievement, occupational performance, or activities of daily living that require these academic skills, alone or in any combination. Specific Learning Disorder (SLD)[10] Descriptive Feature Specifiers Specify which of the following domains of academic difficulties and their subskills are impaired, at the time of assessment: Specific Learning Disorder (SLD)[11] Descriptive Feature Specifiers 1. Reading a) Word reading accuracy b) Reading rate or fluency c) Reading comprehension Specific Learning Disorder (SLD)[12] Descriptive Feature Specifiers 2. Written expression a) Spelling accuracy b) Grammar and punctuation accuracy c) Legible or fluent handwriting d) Clarity and organization of written expression Specific Learning Disorder (SLD)[13] Descriptive Feature Specifiers 3. Mathematics a) Memorizing arithmetic facts b) Accurate or fluent calculations c) Effective math reasoning Etiology of Learning Disabilities [1] Genetic Basis Eight times greater when parents have a reading disorder Higher incidence in identical twins Related to multiple genes transmission Etiology of Learning Disabilities [2] Biological Basis Different patterns of brain activation than non-LD Disruption in the neural systems while reading More irregularities in cerebral blood flow and glucose metabolism than non-LD Etiology of Learning Disabilities [3] Environmental Basis Ineffective learning strategies Pedagogically induced Parental attitudes toward learning Parents’ child-management techniques Family verbal interaction patterns Etiology of Learning Disabilities [4] Environmental Basis (Cont.) Early reading experiences Children’s temperament Children’s level of motivation Family’s socioeconomic status Precursors of LD at Preschool Age [1] Motor Delays in gross-motor development Delays in fine-motor development Behavioral Hyperactivity Impulsivity Inattention Distractibility Precursors of LD at Preschool Age [2] Cognitive/Executive Difficulty in planning ahead Sequence confusion of routine activities Losing clothes, toys, and school materials Memory Memory difficulties Difficulty in acquiring facts, accumulating general knowledge, and learning word sounds Precursors of LD at Preschool Age [3] Communication Speech and language delays Difficulties in learning listening and speaking skills Problems with syntax, articulation, and pragmatics Precursors of LD at Preschool Age [4] Perceptual Visual or auditory processing difficulties Auditory processing difficulties Social-Emotional Difficulties in regulating emotions Difficulties in developing friendships School-Age Children with LD [1] Problems Cognitive/Academic Problems Information-Processing/Executive Problems Perceptual Problems Social-Behavioral Problems School-Age Children with LD [2] Possible Reasons Behavioral problems may stem from learning problems Learning problems may stem from behavioral problems. Both learning and behavioral problems may stem from a common etiology Advantages of Discrepancy Model 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Reliability and validity are known to be adequate. A rationale is provided for dispensing services. The focus is on the core area. The identification procedure is characterized by objectivity. Special education services are provided to those most likely to benefit from them. Disadvantages of Discrepancy Model [1] 1. 2. Clinicians using the same discrepancy formula, but different tests, may arrive at different classifications. Using discrepancy formulas without regard for the absolute level of the child’s performance may result in serious misinterpretations and misclassifications. Disadvantages of Discrepancy Model [2] 3. Discrepancy formulas are based on the assumption that the tests used to evaluate a child’s intelligence and achievement measure independent constructs, when in fact achievement and intelligence tests measure similar constructs (e.g., vocabulary, mathematics, factual information). Disadvantages of Discrepancy Model [3] 4. 5. 6. Discrepancy formulas fail to identify children with learning disabilities who show no discrepancy between achievement and intelligence test scores. Discrepancy formulas have never been empirically validated. The discrepancy formula approach prevents children from receiving services during their early school years. Curriculum Based Measurement (CBM)[1] Designed to monitor students’ growth in basic academic domains Reading Spelling Written expression Mathematics Tied to the curriculum of instruction Curriculum Based Measurement (CBM)[2] Provides teachers with data useful for Comparing how students have done recently on other, similar tasks Evaluating how students are progressing toward a long term goal Making adjustments in instructional level and type of instruction Comparing students to a local group, such as classroom or grade Curriculum Based Measurement (CBM)[3] CBM TESTS Multiple forms of tests are possible Inexpensive to create and produce Sensitive to students’ achievement and change over time Curriculum Based Measurement (CBM)[4] CBM TESTS (Cont.) Standardized assessment Specific directions Timed Scoring rules Can be given repeatedly to the same student Curriculum Based Measurement (CBM)[5] CBM TESTS (Cont.) Tests designed to measure what students were taught and expected to learn Quick, efficient, and easy to give Short duration permits frequent administration Focus on direct and repeated measures of student performance Curriculum Based Measurement (CBM)[6] CBM TESTS (Cont.) Can be used for Eligibility determination Screening Decision-making (both individual, criterion referenced, and norm referenced) Progress monitoring DIBELS (Dynamic Indicators of Basic Early Literacy Skills) [1] EXAMPLE OF A CBM MEASURE Five measures designed to determine if students need additional instructional support Typically, students are tested once in the fall and once in the spring Aim is to determine what instructional modifications should be made DIBELS (Dynamic Indicators of Basic Early Literacy Skills) [2] EXAMPLE OF A CBM MEASURE (Cont.) Initial Sounds Fluency (ISF) 12 pictures are shown Students asked to identify the beginning sound Primarily for kindergarteners Measures basic literacy skills DIBELS (Dynamic Indicators of Basic Early Literacy Skills) [3] EXAMPLE OF A CBM MEASURE (Cont.) Letter Naming Fluency (LNF) Students given a page containing upperand lower-case letters Asked to name as many letters as they can Phoneme Segmentation Fluency (PSF) Students hear distinct words Asked to verbally produce the individual phonemes DIBELS (Dynamic Indicators of Basic Early Literacy Skills) [4] EXAMPLE OF A CBM MEASURE (Cont.) Nonsense Word Fluency (NWF) Students see written CVC (consonant vowel consonant) and VC (vowel consonant) nonsense words Asked to verbally produce the individual sound of each letter or read the whole word DIBELS (Dynamic Indicators of Basic Early Literacy Skills) [5] EXAMPLE OF A CBM MEASURE (Cont.) Oral Reading Fluency (ORF) Students are given a standardized set of reading passages Asked to read the passage out loud in one minute DIBELS (Dynamic Indicators of Basic Early Literacy Skills) [6] SOURCE Kaminski, R. A., & Good, R. H., III. (2005). Dynamic Indicators of Basic Early Literacy Skills—6th Edition (DIBELS-6). Eugene, OR: University of Oregon Academic Competence Evaluation Scales (ACES) [1] ANOTHER EXAMPLE OF A CMB TEST Part of Academic Intervention Monitoring System (AIMS) Academic Skills Subscales Reading/Language Arts Mathematics Critical Thinking Academic Competence Evaluation Scales (ACES) [2] ANOTHER EXAMPLE OF A CMB TEST Part of Academic Intervention Monitoring System (AIMS) Academic Enablers Subscales Motivation Reflects a student’s approach, persistence, and level of interest regarding academic subjects Academic Competence Evaluation Scales (ACES) [3] ANOTHER EXAMPLE OF A CMB TEST Part of Academic Intervention Monitoring System (AIMS) Academic Enablers Subscales (Cont.) Engagement Reflects a student’s attention and active participation in classroom activities Academic Competence Evaluation Scales (ACES) [4] ANOTHER EXAMPLE OF A CMB TEST Part of Academic Intervention Monitoring System (AIMS) Academic Enablers Subscales (Cont.) Study skills Reflects a student’s behaviors that facilitate the processing of new material and taking tests Academic Competence Evaluation Scales (ACES) [5] ANOTHER EXAMPLE OF A CMB TEST Part of Academic Intervention Monitoring System (AIMS) Academic Enablers Subscales (Cont.) Interpersonal skills Reflects a student’s cooperative learning behaviors necessary to interact with others Academic Competence Evaluation Scales (ACES) [6] SOURCE DiPerna, J. C., & Elliott , S. N. (2000). Academic Competence Evaluation Scales (ACES). San Antonio, TX: Pearson Curriculum Based Assessment A test written by a teacher Focus on evaluating what a student learned from the instruction given in a specific course Example: A weekly spelling test based on a spelling list Intellectual Developmental Disorder (IDD)[1] DSM-V, Revised April 2012 Definition: Intellectual Developmental Disorder (IDD) is a disorder that includes both a current intellectual deficit and a deficit in adaptive functioning with onset during the developmental period. Intellectual Developmental Disorder (IDD)[2] Diagnostic Criteria Must meet criteria A, B, and C Intellectual Developmental Disorder (IDD)[3] Diagnostic Criteria A Intellectual Developmental Disorder is characterized by deficits in general mental abilities such as reasoning, problem-solving, planning, abstract thinking, judgment, academic learning and learning from experience. Intellectual Developmental Disorder (IDD)[4] Diagnostic Criteria B Impairment in adaptive functioning for the individual’s age and sociocultural background. Intellectual Developmental Disorder (IDD)[5] Diagnostic Criteria B (Cont.) Adaptive functioning refers to how well a person meets the standards of personal independence and social responsibility in one or more aspects of daily life activities, such as communication, social participation, functioning at school or at work, or personal independence at home or in community settings. Intellectual Developmental Disorder (IDD)[6] Diagnostic Criteria B (Cont.) The limitations result in the need for ongoing support at school, work, or independent life. Intellectual Developmental Disorder (IDD)[7] Diagnostic Criteria C All symptoms must have an onset during the developmental period. Intellectual Developmental Disorder (IDD)[8] DSM-V Discussion of IQ IQ tests in DSM-V. Intellectual functioning is typically measured using standardized tests of intellectual function. Intellectual Developmental Disorder (IDD)[9] DSM-V Discussion of IQ (Cont.) On such tests, the category of IDD is considered to be approximately 2 standard deviations below the population mean. This level of impairment equates to an Intelligence Quotient (IQ) score of 70 or below, with a measurement error of approximately 5 points on each side of the cut point. Intellectual Developmental Disorder (IDD)[10] DSM-V Discussion of IQ (Cont.) Assessment procedures and diagnosis must take into account factors other than IDD that may limit performance (e.g., sociocultural background, native language, associated communication/language disorder, motor or sensory handicap). Intellectual Developmental Disorder (IDD)[11] DSM-V Discussion of IQ (Cont.) Cognitive profiles are generally more useful for describing intellectual abilities than a single full-scale IQ score, and clinical training and judgment are required for interpretation of test results. Intellectual Developmental Disorder (IDD)[12] Severity Level for IDD Mild Moderate Severe Conceptual Domain Conceptual Domain Conceptual Domain Social Domain Social Domain Social Domain Practical Domain Practical Domain Practical Domain Intellectual Developmental Disorder (IDD)[13] Mild Severity Level for IDD Conceptual Domain For preschool children, there may be no obvious conceptual differences. Intellectual Developmental Disorder (IDD)[14] Mild Severity Level for IDD Conceptual Domain (Cont.) For school-aged children and adults, person has difficulties and limitations in acquisition of academic skills involving reading, writing, arithmetic, time, money, and needs support in at least some of these areas in order to meet age-related expectations. Intellectual Developmental Disorder (IDD)[15] Mild Severity Level for IDD Conceptual Domain (Cont.) In adults, abstract thinking, executive function (planning, strategizing, setting priorities, and cognitive flexibility) and short term memory are impaired. Older children and adults may have a concrete approach to problems and solutions compared to agemates. There are usually lifelong limitations in these areas. Intellectual Developmental Disorder (IDD)[16] Mild Severity Level for IDD Social Domain Compared to typically developing agemates, the person is immature in social interactions. For example, there may be difficulty in accurately perceiving peers’ social cues. Communication and language are more concrete than expected for age. Intellectual Developmental Disorder (IDD)[17] Mild Severity Level for IDD Social Domain (Cont.) There may be difficulties regulating emotion and behavior in age-appropriate fashion. These difficulties are noticed and are generally accommodated for by peers in social situations. Social judgment is immature for age and the person is at risk of being manipulated by others (gullibility). Intellectual Developmental Disorder (IDD)[17] Mild Severity Level for IDD Practical Domain Person may function age-appropriately in personal care, though in childhood these skills may not be age-appropriate. Persons need some support with complex tasks in comparison to peers. Intellectual Developmental Disorder (IDD)[17] Mild Severity Level for IDD Practical Domain (Cont.) In adulthood supports typically involve grocery shopping, transportation, organizing home and childcare, nutritious food preparation, banking and money management. Recreational skills resemble those of age-mates, though judgment related to wellbeing and organization around recreation requires support. Intellectual Developmental Disorder (IDD)[17] Mild Severity Level for IDD Practical Domain (Cont.) As adults, persons can work in competitive employment in jobs that do not emphasize conceptual skills. Persons generally need support to make health care decisions, legal decisions, and to learn to perform a vocation competently. Support is typically needed to raise a family. Intellectual Developmental Disorder (IDD)[18] Moderate Severity Level for IDD Conceptual Domain All through development, the person’s conceptual skills lag markedly behind peers. For preschoolers, language and pre-academic skills develop slowly. Progress in reading, writing, math, time, and money occurs gradually across the school years. Intellectual Developmental Disorder (IDD)[19] Moderate Severity Level for IDD Conceptual Domain (Cont.) For adults, academic skill development is typically at an elementary rather than secondary level. Ongoing assistance on a daily basis is needed to complete conceptual tasks of day to day life. Intellectual Developmental Disorder (IDD)[20] Moderate Severity Level for IDD Social Domain Person shows marked differences from peers in social and communicative behavior across development. Spoken language is typically a primary tool for social communication but is less complex than peers. Intellectual Developmental Disorder (IDD)[21] Moderate Severity Level for IDD Social Domain (Cont.) People have social motivation for relationships with family and peers, and may have successful friendships across life and sometimes romantic relations in adulthood. However, people may not perceive or interpret social cues accurately. Intellectual Developmental Disorder (IDD)[22] Moderate Severity Level for IDD Social Domain (Cont.) Social judgment and decision-making abilities are limited, and caretakers must assist the person with life decisions. Friendships with typically developing peers are often affected by communication or social limitations. Social and communicative support is needed in work settings for success. Intellectual Developmental Disorder (IDD)[17] Moderate Severity Level for IDD Practical Domain Person can care for personal needs involving eating, dressing, elimination, hygiene as an adult, though an extended period of teaching and time is needed to become independent in these areas. Intellectual Developmental Disorder (IDD)[17] Moderate Severity Level for IDD Practical Domain (Cont.) Similarly, participation in all household tasks can be achieved by adulthood, though an extended period of teaching and support is needed. Intellectual Developmental Disorder (IDD)[17] Moderate Severity Level for IDD Practical Domain (Cont.) Independent employment may be achieved, but considerable support from co-workers, supervisors, and coaches is needed to manage social expectations, complexities of the job, and ancillary responsibilities such as scheduling, transportation, health benefits, and money management. Intellectual Developmental Disorder (IDD)[17] Moderate Severity Level for IDD Practical Domain (Cont.) A variety of recreational skills can be developed and typically requires additional supports and learning opportunities over an extended period of time. Maladaptive behavior is present in a significant minority and causes social problems. Intellectual Developmental Disorder (IDD)[23] Severe Severity Level for IDD Conceptual Domain Attainment of conceptual skills is extremely limited. Person may understand use of objects as tools, may be able to complete simple cause and effect actions with objects. Intellectual Developmental Disorder (IDD)[24] Severe Severity Level for IDD Conceptual Domain (Cont.) Person lacks understanding of written language. Person lacks concepts involving number, quantity, time, money. Caretakers provide all supports for this area throughout life. Intellectual Developmental Disorder (IDD)[25] Severe Severity Level for IDD Social Domain Persons generally use nonverbal communication to initiate and respond to social attention and interactions. Language, if used or understood, involves names of objects and people and simple phrases tied to everyday events. Intellectual Developmental Disorder (IDD)[26] Severe Severity Level for IDD Social Domain (Cont.) Persons may respond to direct emotional communications and understand simple social cues but in general lack understanding of social context. Relationships involve family, caretakers and other long term ties and are more typical of attachment relations than of reciprocal friendships. Intellectual Developmental Disorder (IDD)[17] Severe Severity Level for IDD Practical Domain Person requires support for all activities of daily living, including meals, dressing, bathing, elimination. Person requires supervision at all times. Intellectual Developmental Disorder (IDD)[17] Severe Severity Level for IDD Practical Domain (Cont.) Person may make choices for preferred objects, activities, and people. Person cannot make responsible decisions regarding wellbeing of self or others. As an adult, participation in practical and vocational activities requires ongoing support and assistance. Intellectual Developmental Disorder (IDD)[17] Severe Severity Level for IDD Practical Domain (Cont.) Recreational activities require long-term teaching and ongoing support. Maladaptive behavior, including self injury, is present in a significant minority. Strategies Useful for Coping with Stress [1] Exercise, Nutrition, and Sleep Strategies Recognize and monitor any symptoms of stress by listening to your body and mind Breathe deeply, with regular slow breathing Exercise (take walks, participate in sports that you enjoy, work in your garden) Strategies Useful for Coping with Stress [2] Exercise, Nutrition, and Sleep Strategies (Cont.) Eat a balanced diet, with plenty of fruits and vegetables Get sufficient sleep Strategies Useful for Coping with Stress [3] Social and Personal Strategies Maintain a sense of humor Devote time to hobbies or other activities that you love Make friends; do not be a social isolate Strategies Useful for Coping with Stress [4] Social and Personal Strategies (Cont.) Know your limits, stick to them, and learn how to say “no” Make your home environment as pleasant as possible (and your work environment as well) Express your feelings to a good friend or therapist (if needed) Strategies Useful for Coping with Stress [5] Social and Personal Strategies (Cont.) Adjust your standards if you are a perfectionist Don’t try to control events (or other people) in your life that are uncontrollable Take a moment to reflect on the positive things in your life Strategies Useful for Coping with Stress [6] Social and Personal Strategies (Cont.) Manage your time effectively Change your pace, making a conscious effort to slow down and not do too much at once or during a day Set aside some time to relax (and learn relaxation techniques as needed) Strategies Useful for Coping with Stress [7] Social and Personal Strategies (Cont.) Take breaks as needed Spend time in nature Play with a pet Watch a comedy Strategies Useful for Coping with Stress [8] Work-Related Strategies Give yourself plenty of time to complete tasks and assignments Reduce overtime Make efforts to create a manageable workload, resisting the temptation to volunteer for additional work or responsibility Strategies Useful for Coping with Stress [9] Work-Related Strategies (Cont.) Consult with colleagues whenever you have questions about how to handle a difficult case Keep your work goals realistic Clarify ambiguous work assignments Strategies Useful for Coping with Stress [10] Work-Related Strategies (Cont.) Keep lines of communication with other staff members open Vary your work activities and the types of clients you work with, if possible Strategies Useful for Coping with Stress [11] Work-Related Strategies (Cont.) Attend lectures, seminars, or conferences, where you can renew your energy for the job and meet others in your field who confront similar problems Take a vacation, during which you ignore your emails, and give yourself time to disengage and unwind Strategies Useful for Coping with Stress [12] Sources Corey, G., Corey, M. S., & Callanan, P. (1993). Issues and ethics in the helping professions (4th ed.). Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole. Helpguide.org. (2008). Stress management: How to reduce, prevent, and cope with stress. Retrieved from http://grad.auburn.edu/cs/stress.pdf Strategies Useful for Coping with Stress [13] Sources Holland, J. C. (1989). Stresses on mental health professionals. In J. C. Holland & J. H. Rowland (Eds.), Handbook of psychooncology: Psychological care of the patient with cancer (pp. 678–682). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. Strategies Useful for Coping with Stress [14] Sources Mateer, C. A., & Sira, C. S. (2008). Practical rehabilitation strategies in the context of clinical neuropsychology feedback. In J. E. Morgan & J. H. Ricker (Eds.), Textbook of clinical neuropsychology (pp. 996–1007). New York, NY: Psychology Press. Children Learn What They Live by Dorothy Law Nolte [1] If children live with criticism, They learn to condemn. If children live with hostility, They learn to fight. If children live with ridicule, They learn to be shy. If children live with shame, They learn to feel guilty. If children live with encouragement, They learn confidence. Children Learn What They Live by Dorothy Law Nolte [2] If children live with tolerance, They learn to be patient. If children live with praise, They learn to appreciate. If children live with acceptance, They learn to love. If children live with approval, They learn to like themselves. Children Learn What They Live by Dorothy Law Nolte [3] If children live with honesty, They learn truthfulness. If children live with security, They learn to have faith in themselves and others. If children live with friendliness, They learn the world is a nice place in which to live.