Lecture 5

advertisement

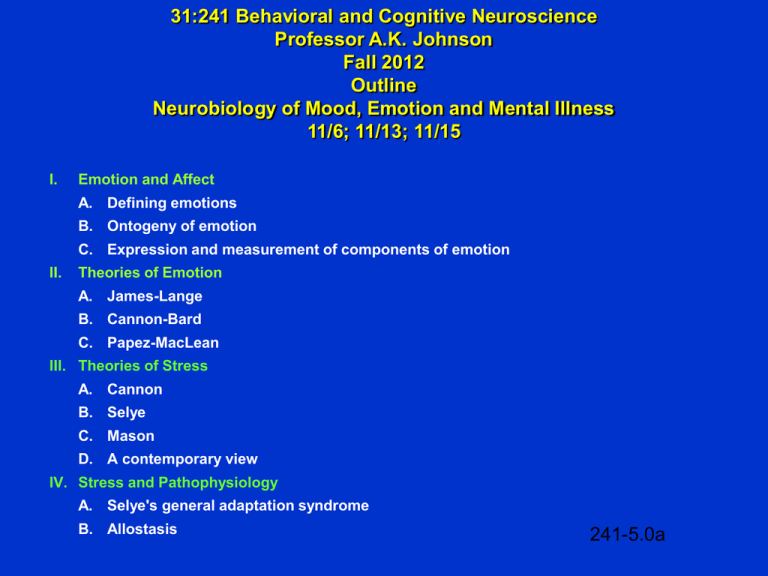

31:241 Behavioral and Cognitive Neuroscience Professor A.K. Johnson Fall 2012 Outline Neurobiology of Mood, Emotion and Mental Illness 11/6; 11/13; 11/15 I. Emotion and Affect A. Defining emotions B. Ontogeny of emotion C. Expression and measurement of components of emotion II. Theories of Emotion A. James-Lange B. Cannon-Bard C. Papez-MacLean III. Theories of Stress A. Cannon B. Selye C. Mason D. A contemporary view IV. Stress and Pathophysiology A. Selye's general adaptation syndrome B. Allostasis 241-5.0a Neurobiology of Mood, Emotion and Mental Illness (Continued) V. Neural and Neurochemical Substrates of Fear and Anxiety A. B. C. D. VI. The defense response and the conditioned emotional response (CER) 1. Neural pathways Neurochemistry 1. CRH 2. GABA Anxiety Disorders Somatic disease, stress and the defense response Depression A. Mood disorders introduction B. Epidemiology and genetics of depression C. Physiological and biochemical correlates of depression 1. Autonomic and cardiovascular changes 2. Endocrine and cytokine 3. Biological rhythms - Seasonal affective disorder D. Theories of Depression 1. Biogenic-amine 2. Stress and the brain–pituitary-adrenal dysfunction 3. Sickness behavior, inflammatory cytokines and depressive symptomatology 4. Stress-Impaired neurogenesis E. Antidepressant drugs and electroconvulsive shock 241-5.0b Key Terms and Concepts Anhedonia Allostasis Allostatic load Amygdala Arousal Basic emotions Brain-deprived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) Cannon-Bard theory of emotion Conditioned emotional response (CER) Corticotropic releasing hormone (CRH) or factor (CRF) Defense response Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) Emotional response General adaptation syndrome (GAS) Generalized anxiety disorder Leukocytes MacLean's visceral brain (limbic system) theory of emotion Median forebrain bundle Monamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOI) antidepressants Nociceptors Nucleus accumbens Panic disorder Papez theory of emotion Periaqueductal gray (PAG) Post-traumatic stress syndrome Simple phobia Social phobia Stress Stress response Stressor Subjective feelings Tricyclic/polycyclic (TCA) antidepressants William James' theory of emotion 241-5 KTC Examples of Lists of Basic Emotions • • • • Surprise Interest Joy Rage • Surprise • Happiness • Anger • • • • Fear Disgust Shame Anguish • Fear • Disgust • Sadness 241-5.1 A Scheme Proposed by Bridges for the Development of Emotions 241-5.2 Types of Emotional Responses Emotional Action Feelings Feelings Emotional Expression Subjective Feelings 241-5.3 Darwin's Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals 241-5.4 Commonality of Emotional Expression in the Faces of Animals and People 241-5.5 William James' Theory of Emotion 241-5.6 Cannon-Bard Theory of Emotion 241-5.7 The Papez Circuit Theory of Emotion 241-5.8 MacLean's Visceral Brain (Limbic System) Theory of Emotion 241-5.9 Originators and Popularizers of the Concept of Stress W.B. Cannon Cannon (1920's) used the term "stress" to characterize the physical impact of averse stimuli on an organism much as an engineer uses the term stress and strain to characterize the effect of a load placed on steel structures. Hans Selye Selye (1936) used the term stress to account for the generalized physiological response to different averse insults to the body. 241-5.10 Evolution of the Concept of Stress 241-5.11 Adaptive Effects of the Stress Response Immediate increase of metabolic fuel Increased oxygen intake Optimization of blood flow to key tissues Inhibition of digestion, growth immune function, reproduction and pain perception Enhancement of sensory intake and memory 241-5.12 Selye's General Adaptation Syndrome (GAS) and the Consequence of Another Stressor Original Stress Normal New Stress 241-5.13 Pathological State Associated with Chronic Stress Fatigue, myopathy; steroid diabetes Hypertension Peptic ulcers Psychosocial dwarfism Impotence; anovulation; loss of libido Impaired disease resistance; cancer Accelerated neural degeneration during aging 241-5.14 Allostasis and Allostatic Load Idea evolved from concepts of homeostasis and stress. Bruce McEwen P. Sterling and J. Eyer were the originators of the concept. Allo – prefix meaning variable. Allostasis = maintaining stability through change; the active process of maintaining a physiological function in the face of a challenge by old control systems adjusting level of function or "new" systems being activated. Systems involved in the stress response show dramatic responses. Allostatic load = wear and tear on the body that results from repeated or sustained activation of processes that maintain homeostasis. Popularizer of Allostasis and Allostatic Load 241-5.15 The Cardiovascular Defense Response 241-5.16 Brain Stimulation-Induced Defense Response Behavioral • Piloerection • Hissing • Halloween Posture Cardiovascular • • • • • Cardiac Output ( HR) Blood Pressure Skeletal Muscle Blood Flow Renal Blood Flow Mesenteric Blood Flow 241-5.17 The Conditioned Emotional Response (CER): A Rat Undergoing Fear Conditioning 241-5.18 Neural Pathways Mediating the Cardiovascular (A) and the Behavioral (Freezing) (B) Components of the Defense Response 241-5.19 The Amygdala and Fear 241-5.20 Stress Pathways and the Control of Glucocorticoids 241-5.21 The Physiological Effects of CRF 241-5.22 Putative CRF Pathways and CRF1 (a) and CRF2 (b) Receptor Localization 241-5.23 Effects of Amygdala Lesions on the CRF Enhancement of the Startle Response 241-5.24 The Projections of the Amygdala That Mediate Behavioral, Physiological and Endocrine Responses to Fear Stimuli 241-5.25 There is a Key Role for GABA in Controlling Activity of the Amygdala 241-5.26 The GABA Synapse 241-5.27 GABA Synthesis COOH COOH CH2 CH2 Glutamic Acid CH2 H2N + CO2 Decarboxylase CH COOH Glutamic Acid CH2 H2 N CH2 GABA 241-5.28 The Interplay Between Neurons and Glia in GABA Metabolism 241-5.29 Schematic Model of the GABAA Receptor Complex BDZ, benzodiazepine 241-5.30 Anxiety Disorders 241-5.31 The Defense Response as an Inducer of Chronic Hypertension Björn Folkow Hypothalamic Stimulation Producing the Defense Response and Chronic Hypertension About 50 years ago, Folkow hypothesized that sustained or repeated activation of the defense response predisposes towards developing chronic hypertension. 241-5.32 Multiple Environmental Stressor-Induced Hypertension 241-5.33 Mood Disorders 241-5.34 Major Depression • Major depression is the leading cause of disability in the U.S. and worldwide. • Depressive disorders affect an estimated 9.5% of adult Americans ages 18 and over in a given year, or about 18.8 million people in 1998. 241-5.35 Distribution of Mood Disorders in the U.S. Population 241-5.36 Symptoms and Signs of Major Depression* • Must include either pervasive depressed mood (verbal report) or pervasive loss of ability to experience pleasure or interest in other things (anhedonia). • Must include at least five of the following: - Depressed mood (require verbal report) - Feelings of worthlessness or guilt (require verbal report) - Diminished concentration (require verbal report) - Recurrent thoughts of death or suicide (require verbal report) - Weight change - Sleep disturbance - Psychomotor agitation or retardation - Fatigue or loss of energy - Loss of pleasure (anhedonia) or interest *Adapted form DSM-IV-RT 241-5.37 DSM-IV-RT Diagnostic Criteria for Dysthymic Disorder A. B. C. D. E. F. G. H. Depressed mood for most of the day, for more days than not, as indicated either by subjective account or observation by others, for at least 2 years. Note: In children and adolescents, mood can be irritable and duration must be at least 1 year. Presence, while depressed, of two (or more) of the following: • Poor appetite or overeating • Insomnia or hypersomnia • Low energy or fatigue • Low self-esteem • Poor concentration or difficulty making decisions • Feelings of hopelessness During the 2-year period (1 year for children or adolescents) of the disturbance, the person has never been without the symptoms in Criteria A and B for more than 2 months at a time. No Major Depressive Episode has been present during the first 2 years of the disturbance (1 year for children and adolescents); i.e., the disturbance is not better accounted for by chronic Major Depressive Disorder, or Major Depressive Disorder, In Partial Remission. Note: There may have been previous Major Depressive Episode provided there was a full remission (no significant signs or symptoms for 2 months) before development of the Dysthymic Disorder. In addition, after the initial 2 years (1 year in children or adolescents) of Dysthymic Disorder, there may be superimposed episodes for Major Depressive Disorder, in which case both diagnoses may be given when the criteria are met for a Major Depressive Episode. There has never been a Manic Episode, a Mixed Episode, or a Hypomanic Episode, and criteria have never been met for Cyclothymic Disorder. The disturbance does not occur exclusively during the course of a chronic Psychotic Disorder, such as Schizophrenia or Delusional Disorder. The symptoms are not due to the direct physiological effects of a substance (e.g., a drug of abuse, a medication) or a general medical condition (e.g., hypothyroidism). The symptoms cause clinically significant distress or impairment in the social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning. Specify if: Early Onset: if onset is before age 21 years Late Onset: if onset is age 21 years or older Specify (for most recent 2 years of Dysthymic Disorder): 241-5.38 With Atypical Features Criteria for Manic Episode A. A distinct period of abnormally and persistently elevated, expansive, or irritable mood, lasting at least 1 week (or any duration if hospitalization is necessary). B. During the period of mood disturbance, three (or more) of the following symptoms have persisted (four if the mood is only irritable) and have been present to a significant degree: • Inflated self-esteem or grandiosity • Decreased need for sleep (e.g., feels rested after only 3 hours of sleep) • More talkative than usual or pressure to keep talking • Flight of ideas or subject experience that thoughts are racing • Distractibility (i.e., attention too easily drawn to unimportant or irrelevant external stimuli) • Increase in goal-directed activity (either socially at work or school, or sexually) or psychomotor agitation • Excessive involvement in pleasurable activities that have a high potential for painful consequences (e.g., engaging in unrestrained buying sprees, sexual indiscretions, or foolish business investments) C. The symptoms do not meet criteria for a Mixed Episode. D. The mood disturbance is sufficiently severe to cause marked impairment in occupational functioning or in usual social activities or relationships with others, or to necessitate hospitalization to prevent harm to self or others, or there are psychotic features. E. The symptoms are not due to the direct physiological effects of a substance (e.g., a drug of abuse, a medication, or other treatment) or a general medical condition (e.g., hyperthyroidism). Note: Manic-like episodes that are clearly caused by somatic antidepressant treatment (e.g., medication, electroconvulsive therapy, light therapy) should not count toward a diagnosis of Bipolar 1 Disorder. 241-5.39 Male/Female Prevalence of Affective Disorders 241-5.40 Genetic Component of Behavioral/Mental Disorders 241-5.41 Confirmed Linkages in Bipolar Disorder Genomic Location Principle Report Independent Confirmations 18p11.2 Berrettini et al., 1994 (38) and 1997 (39) Stine et al., 1995 (40); Nothen et al., 1999 (41); Turecki et al., 1999 (42) 21q22 Straub et al., 1994 (44) Detera-Wadleigh et al., 1996 (45); Smythe et al., 1996 (46); Kwok et al., 1999 (47); Morissette et al., 1999 (48) 22q11-13 Kelsoe et al., 2001 (49) Detera-Wadleigh et al., 1997 (50) and 1999 (51) 18q22 Stine et al., 1995 (40) Mcinnes et al., 1996 (52); McMahon et al., 1997 (53); De Bruyn et al., 1996 (54) 12q24 Morissette et al., 1999 (48) Ewald et al., 1998 (56); Detera-Wadleigh et al., 1999 (51) 4p15 Blackwood et al., 1996 (57) Ewald et al., 1998 (58); Nothen et al., 1997 (59); Detera-Wadleigh et al., 1999 (51) 241-5.42 Physiological and Biochemical Signs in Depression Vegetative • • • • Increased heart rate Decreased heart rate variability Increased cardiovascular reactivity to psychosocial stressors Increased susceptibility to heart disease Endocrine • • • • Increased plasma norepinephrine Increased cerebrospinal fluid CRF Increased plasma corticosterone Altered cytokines in depressed mood Circadian • • • • • • Altered sleep cycles Increased REM Decreased REM onset latency Sleep deprivation and depression Altered CRF cycle Seasonal affective disorder 241-5.43 Average Plasma Cortisol Concentrations 241-5.44 Patterns of the Stages of Sleep of a Normal Subject and of a Patient with Major Depression 241-5.45 Changes in the Depression Rating of a Depressed Patient Produced by a Single Night's Total Sleep Deprivation Mean Mood Rating of Responding and Non-Responding Patients Deprived of One Night's Sleep as a Function of the Time of Day 241-5.46 Seasonal Affective Disorder (SAD) • Distinctive constellation of symptoms including - Overeating - Oversleeping - Carbohydrate craving • Triggered by light deficiency • Responds to phototherapy • Theories accounting for the antidepressant effects of phototherapy - Melatonin hypothesis - Circadian phase shift - Circadian rhythm amplitude 241-5.47 Light Box Therapy May Ameliorate Seasonal Affective Disorder (SAD) 241-5.48 Biological Theories of Depression I. Monoamine Theory of Depression • The monoamine theory, proposed in 1965, suggests that depression results from functionally deficient monoaminergic (norepinephrine and/or 5-HT) transmission in the CNS. • The theory was based on the ability of known antidepressant drugs (TCA and MAOI) to facilitate monoaminergic transmission, and of drugs such as reserpine to cause depression. • Other pharmacological evidence fails to support the monoamine hypothesis. • Biochemical studies on depressed patients do not, in general, support the monoamine hypothesis, except that consistently low concentrations of 5-HIAA in the CSF are found. • Though the monoamine hypothesis in its simple form is no longer tenable as an explanation of depression, pharmacological manipulation of monoamine transmission remains the most successful therapeutic approach. 241-5.49 Pharmacological Evidence Relating to the Monoamine Hypothesis of Depression Drug Principal Action Effect in Depressed Patients Effects consistent with the hypothesis Reserpine Inhibits NE and 5-HT storage Mood Tricyclic antidepressants Block NE and 5-HT re-uptake Mood MAO inhibitors Increase stores of NE and 5-HT Mood -methyltyrosine Inhibits NE synthesis Mood ; calming of manic patients Methyldopa Inhibits NE synthesis Mood Electroconvulsive therapy Increases CNS response to NE and 5-HT Mood 241-5.50 Pharmacological Evidence That Does Not Support the Monoamine Hypothesis of Depression Drug Principal Action Effect in Depressed Patients Amphetamine Releases NE and blocks re-uptake None. Euphoria in normal subjects Cocaine Inhibits NE re-uptake None. Euphoria in normal subjects Tryptophan (5-hydroxytryptophan) Increases 5-HT synthesis Mood? but only in some studies - and -adrenoceptor antagonists Blocks actions of NE Mood slightly ↓ with -adrenoceptor antagonists; No effect on manic patients Methysergide 5-HT receptor antagonist None L-dopa Increases NE synthesis None Iprindole No effect on amine metabolism Mood 241-5.51 Stahl's Hypothesis for Specific Syndromes Associated with Different Kinds of Monoamine Deficiencies Norepinephrine Deficiency Syndrome • • • • • • • Depressed mood Impaired attention Problems concentrating Deficiencies in working memory Slowness of information processing Psychomotor retardation Fatigue Serotonin Deficiency Syndrome • • • • • Depressed mood • Food craving; bulimia Anxiety Panic Phobia Obsessions and compulsions 241-5.52 Biological Theories of Depression II. Evidence for a CRF-HPA Theory of Depression Corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) in cerebrospinal fluida,b Blunted adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) -endorphin to CRF stimulationa Density of CRF receptors in frontal cortex of patients who commit suicide Pituitary gland enlargement in depressed patientsb Adrenal gland enlargement in depressed patients and patients who commit suicideb Cortisol production during depressiona Plasma glucocorticoid, ACTH, and -endorphin non-suppression after dexamethasone administrationa Urinary free cortisol concentrations aState-dependent bSignificantly correlated to post-dexamethasone cortisol concentrations 241-5.53 Biological Theories of Depression III. Macrophage Theory of Depression -- R.S. Smith Medical Hypotheses 35:298-306, 1991 Seven Lines of Support 1. Volunteers given monokines (IL-1; INF-; TNF) develop symptoms of a major depressive episode. 2. IL-1 can account for hormonal abnormalities (e.g., ACTH; GH). 3. Diseases and cohorts characterized by macrophage activation are associated with high rates of depression. 4. Brain macrophages (microglia) secrete monokines. 5. Estrogen increases IL-1 secretion by macrophages. 6. Eicosapentaenoic acid suppresses macrophages, whereas linoleic acid activates them. 7. Substantial epidemiology is consistent with this hypothesis. 241-5.54 Biological Theories of Depression IV. Stress-Induced Neurodegeneration 241-5.55 Drugs Used in Affective Disorders: Antidepressants Reuptake Inhibition Drug Name Generic (Trade) Sedative Activity Tricyclic Compounds Imipramine (Tofranil) Moderate Desipramine (Norpramin) Low Trimipramine (Surmontil) High Protriptyline (Vivactil) Low Nortriptyline (Pamelor, Aventil) Moderate Amitriptyline (Elavil) High Doxepin (Adapin, Sinequan) High Clomipramine (Anaframil) Low Second-Generation (Atypical) Compounds Amoxapine (Asendin)b Low Maprotiline (Ludiomil) Moderate Trazodone (Desyrel) Moderate Bupropion (Wellbutrin) Low Venlafaxine (Effexor) None Serotonin-Specific Reuptake Inhibitors Fluoxetine (Prozac) None Sertraline (Zoloft) None Paroxetine (Paxil) None Citalopram (Celexa) None Fluvoramine (Luvox) None Dual-Action Antidepressant Mirtazapine (Remeron) High MAO Inhibitors: Irreversible Phenelzine (Nardil) Low Isocarboxazid (Marplan) None Tranylcypromine (Parnate) None MAO Inhibitor: Reversible Moclobemide (Aurorix)d None Norepinephrine-Specific Reuptake Inhibitor Reboxetine (Edronax) None Anticholinergic Activitya Elimination Half-Life (hr) NE Serotonin Dopamine Moderate Low Moderate Moderate Low High High Low 10-20 12-75 8-20 55-125 15-35 20-35 8-24 19-37 ++ +++ + +++ ++ ++ ++ ++ ++ + + + ++ ++ ++ ++++ 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Moderate Moderate Low Low None 8-10 27-58 6-13 8-14 3-11 ++ +++ 0 0/+ ++ + 0 ++ 0/+ ++++ 0 0 0 ++ 0 None None None None None 24-96 26 24 33 15 0 0 + 0 0 ++++ ++++ ++++ ++++ ++++ 0 0 0 0 0 Low 20-40 ++ ++++ 0 None None None 2-4c 1-3c 1-3c 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Low 1-3c 0 0 0 Low 13 ++++ 0 0 aAnticholinergic side effects include dry mouth, blurred vision, tachycardia, urinary retention, and constipation. bAlso has antipsychotic effects due to blockage of dopamine receptors. cHalf-life does not correlate with clinical effects. dNot available for use in the US. 0=no effect; +=mild effect; ++=moderate effect; +++= strong effect; ++++=maximal effect. 241-5.56 Changes in Adrenergic Receptors and in Norepinephrine Synthesis and Release with Chronic Antidepressant Treatment (Reuptake Inhibitors) 241-5.57 Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors Drugs • Fluoxetine • Sertraline Advantages • Fewer anticholinergic and cardiovascular side effects • However relatively new and long-term effects need to be evaluated 241-5.58 Changes Induced with Chronic Treatment with Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors 241-5.59 Long-Term Adaptations to Antidepressant Treatment 241-5.60 Progression of Changes in the Pharmacological Treatment of Major Depressive Disorder 241-5.61 Electroconvulsive Therapy (ECT) • 1900's observed that spontaneous seizures improved psychiatric state • Early seizures induced with camphor and oil • 1938 ECT • ECT generally used on depressed patients unresponsive to pharmacotherapy • Its efficacy is 80% to 90% which is higher than conventional therapies • Technically difficult and expensive • Must be administered several times a week for several weeks • Mood changes are due to cortical seizures and not to peripheral results • Mechanisms are not known 241-7.62