Psychosis and Spirituality

advertisement

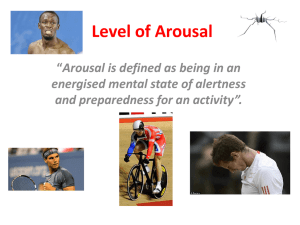

Psychosis and Spirituality Isabel Clarke Consultant Clinical Psychologist Southern Health Foundation NHS Trust Outline of the Session Introduce the idea of 2 ways of experiencing Leading into a psychological understanding of spirituality – using Interacting Cognitive Subsystems (Teasdale & Barnard 1993). Leading into a new way of understanding the human being Applying this clinically: The ‘What is Real Programme’ Some Questions What are the characteristics of spiritual experience ? What are the characteristics of psychotic experience ? Two Ways of Experiencing The other one! Characteristics of the other way of experiencing Metaphor come to life Dissolution of boundaries Cosmic significance – terrible or wonderful Confusion about the self Coincidence rules OK Threat (cosmic) Link with trauma O the mind, mind has mountains; cliffs of fall Frightful, sheer, no-manfathomed. Hold them cheap May who ne’er hung there. Gerald Manley Hopkins (from ‘No worst, there is none, pitched past pitch of grief’) Travel into the strange places of the mind Not mind safely locked inside the skull; No!: mind that envelopes us; Mind that is sea we swim in Travel across the threshold – the Transliminal – but never to let go of Ariadne’s thread! Spirituality and Relationship As people, we make sense only within our context of relationship –we are held in a web of relationship Important others; our family; our social group; ethnic group etc. Spirituality is about relationship with that which is beyond; with the whole – the widest circle of the web At times of breakdown, that wider context becomes important Different types of experience: psychosis and spirituality revisited. Mental health breakdown is a common human experience Comes from a combination of Individual vulnerability/sensitivity Life circumstances – losses etc. Leading to unmanageable feelings It often happens at times of transition Why can some people manage to adust to difficult transitions Whereas other people find themselves in a different dimension? How is it that for some people this experience is creative and transformative? Whereas for others it is the opposite? What can we learn about this other dimension – and how can this help us to stand beside the journier? What is going on here? The levels of processing problem Being human is difficult because our brains have 2 main circuits – they work together most of the time, but not always. There is one direct, sensory driven type of processing and a more elaborate and conceptual one. The same distinction can be found in the memory. Direct processing is emotional and characterised by high arousal. The other one filters our view to make it more manageable The direct processing system is the default system – the one that dominates if the other gets disconnected – in which case we lose that filter – and land up ACROSS THE THRESHOLD –THE TRANSLIMINAL Getting a scientific grip on the transliminal The split between realities comes from the split in us! Interacting Cognitive Subsystems provides a way of making sense of this ‘crack’.(Teasdale & Barnard 1993). An information processing model of cognition Developed through extensive research into memory and limitations on processing. A way into understanding the “Head/Heart split in people. Interacting Cognitive Subsystems. Body State subsystem Implicational subsystem Implicational Memory Auditory ss. Visual ss. Propositional subsystem Propositional Memory Verbal ss. Linehan’s STATES OF MIND (from Dialectical Behaviour Therapy) – Maps onto Interacting Cognitive Subsystems REASONABLE WISE MIND EMOTION MIND MIND (Propositional (Implicational subsystem) subsystem) WISE MIND IN THE PRESENT IN CONTROL Important Features of this model Our subjective experience is the result of two overall meaning making systems interacting – neither is in control. Each has a different character, corresponding to “head” and “heart”. The IMPLICATIONAL Subsystem manages emotion – and therefore relationship. The verbal, logical, PROPOSITIONAL ss. gives us our sense of individual self. Two Ways of Knowing Good everyday functioning = good communication between implicational/relational and propositional At high and at low arousal, the implicational ss becomes dominant This gives us a different quality of experience – one that can be either valued and sought after, or shunned and feared A Challenging Model of the Mind The human being is a balancing act as the two organising systems pass control back and forth: there is no boss. The mind is simultaneously individual, and reaches beyond the individual, when the implicational ss. is dominant. This constant switch between logic and emotion gives us human fallibility The self sufficient, billiard ball, mind is an illusion In our implicational/relational mode we are a part of the whole. ‘That’s How the Light gets in’ (and the dark) The Relational part of our mind is embedded in relationship; in the whole (the older part) The newer, self conscious, part holds our individuality Temporary control passing backwards and forwards between the two organising ss is experienced as normality When the ‘relational’ takes over for any length of time, the character of experience changes The person is no longer grounded in their individuality – boundaries dissolve – they are open to any influences – positive and negative. The Everyday Ordinary Clear limits Access to full memory and learning Precise meanings available Separation between people Clear sense of self Emotions moderated and grounded A logic of ‘Either/Or The Transliminal Numinous Unbounded Access to propositional knowledge/memory is patchy Suffused with meaning or meaningless Self: lost in the whole or supremely important Emotions: swing between extremes or absent A logic of ‘Both/And’ Managing the threshold Awareness of vulnerability – of openness to transliminal experience Grounding when the experience is overwhelming. Grounding activity. Grounding food. Mindfulness to manage the threshold Challenge of facing unshared reality mindfully – both pleasant and unpleasant Transliminal state of mind = most accessible at high and low arousal Managing arousal – breathing control to reduce arousal; mindful activity in the present to prevent it slipping. Web of Relationships In Rel. with earth: non humans etc. primary care-giver In Rel. with wider group etc. Self as experienced in relationship with primary caregiver Sense of value comes from rel. with the spiritual Unpacking the Web We learn about ourselves from the way the important people around us treat us from babyhood on. The function of emotions is the organisation of relationship: relationship with others, but also our relationship with ourselves. Emotions communicate directly between people, bypassing the verbal-logical (they are catching). Looking Beyond the Individual – to understand Spirituality We are defined by relationships that go beyond our current human bonds These include relationship with our ancestors and those who will come after us Moving out to relationship with our group, nation, other peoples, humanity Our relationship with the non human creatures is deep and significant for us Further dimensions of relationship Relationship with place, with the earth, our planet Relationship with that which is deepest and furthest – which is beyond our naming capacity, but is sometimes called God, Goddess, Spirit etc. Relationship is something we experience – so it can be beyond propositional knowledge – we can feel more than we know. Psychosis and Relationship Psychosis might be about getting lost on the wrong side of the threshold – the place of relationship But we need our propositional to manage immediate human relationships – and life in general It is no accident that it is those people diagnosed as psychotic who are often most concerned with the spiritual I suggest we need to respect their connection with that valued part of human experience – while developing ‘threshold management’ Taking Experience Seriously in Psychosis Acknowledging that psychosis feels different Normalising the difference in quality of experience as well as the continuity Positive side as well as vulnerability • Helping people to manage the threshold – mindfulness is key Sensitivity and openness to anomalous experience – continuum with normality: Gordon Claridge’s Schizotypy research. Understanding the role of emotion – the feeling is real even though the ‘story’ can be suspect. Evidence for a new normalisation Schizotypy – a dimension of experience: Gordon Claridge. Mike Jackson’s research on the overlap between psychotic and spiritual experience. Emmanuelle Peter’s research on New Religious Movements. Caroline Brett’s research: having a context for anomalous experiences makes the difference between whether they become diagnosable mental health difficulties and whether the anomalies/symptoms are short lived or persist. (New chapters by Brett and Jackson in Psychosis and Spirituality: consolidating the new paradigm – along with new qualitative research) Wider sources of evidence – e.g.Cross cultural perspectives; anthropology. Richard Warner: Recovery from Schizophrenia. The What is Real and What is Not Programme First : Form an Alliance. Validate their reality Introduce the idea that their reality is only one way of looking at it: shared and unshared reality (negotiate the language). The individual’s experience is taken seriously and valued – at the same time as working on a better relationship to shared experience It is possible to get away from illness language – and arguments about diagnosis Normalising openness to unshared reality – idea of the schizotypy spectrum Advantages and disadvantages of openness to unshared reality – e.g. of people who have used unshared reality positively. Characteristics of unshared reality. Idea of the line/ the threshold. Importance of being able to manage the line Motivational aspect – pros and cons. Coping skills to manage the line When is unshared reality most powerful; in charge? Arousal as a means of being in control; Stress management Being alert and concentrated – watch out for drifting states Grounding in the present Wise mind and mindfulness Focusing/mindfulness v. distraction Session 2. The role of Arousal shaded area = anomalous experience/symptoms are more accessible. Level of Arousal High Arousal - stress Ordinary, alert, concentrated, state of arousal. Low arousal: hypnagogic; attention drifting etc. Making sense of the experience Discussion: Why do people click into/get lost in unshared reality/the transliminal? Discussion of Different meanings for the experience Meaning for the individual Place in their life – what was happening in their life when it all started? Address and validate the emotion – that is reliable. 'Problem Solving' idea – Mike Jackson’s research. Touching on the transformative potential of the transliminal. A way of working with psychosis that normalises the spiritual dimension. Validating the person’s experience, and helping them to manage the threshold between the two ways of experiencing. Mobilising and nurturing strengths Persuasion to join “shared reality” – need to be honest about the risks. “Sensitivity” – normalisation based on Claridge’s work on schizotypy. The person’s important context of relationships needs attending to – a lifeline. Creative expression Helping someone get their bearings by mapping the 2 states. These sorts of experiences can be very confusing and disorienting – it helps it someone can come up with a map. Explain that there are 2 states, and some people are more open than others Find a way of describing this that works for your client (e.g. ‘Your Reality’ and ‘Shared Reality’ Draw out two columns Sort out the person’s story into the two – being very tactful where you are suggesting that it lies in the nonshared side – hint: Non-shared reality has a ‘both-and’ logic – 2 incompatible things can be true at the same time! This can be used as a framework for future sessions. Contact details, References and Web addresses Isabel.Clarke@hantspt-sw.nhs.uk AMH Woodhaven, Calmore, Totton SO40 2TA. Clarke, I. (Ed.) (2010) Psychosis and Spirituality: consolidating the new paradigm. Chichester: Wiley Clarke, I. ( 2008) Madness, Mystery and the Survival of God. Winchester:'O'Books. Clarke, I. & Wilson, H.Eds. (2008) Cognitive Behaviour Therapy for Acute Inpatient Mental Health Units; working with clients, staff and the milieu. London: Routledge. Durrant, C., Clarke, I., Tolland, A. & Wilson, H. (2007) Designing a CBT Service for an Acute In-patient Setting: A pilot evaluation study. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy. 14, 117-125. Wilson, H, Clarke, I & Phillips,R.,(in submission) Evaluation of an Inpatient Group CBT for Psychosis Program Designed to Increase Effective Coping and Address the Stigma of Diagnosis Psychosis. www.isabelclarke.org www.SpiritualCrisisNetwork.org.uk