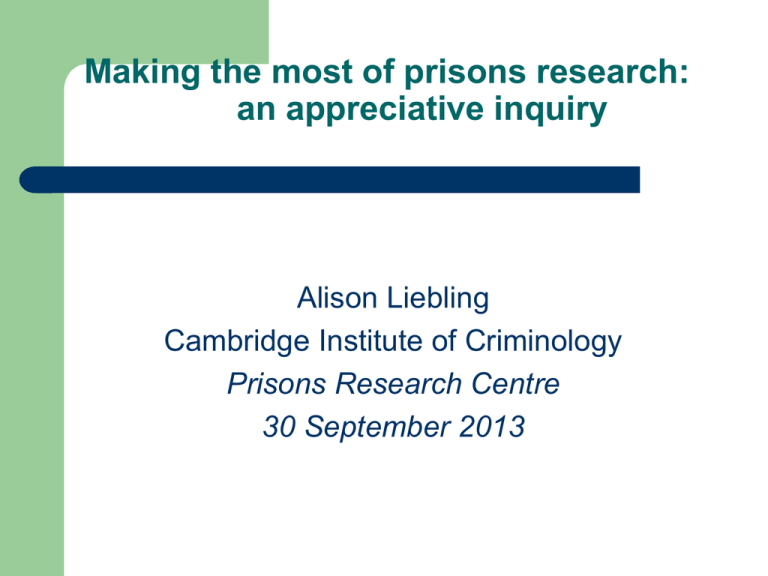

MQPL I: Limitations - Global Centre for Evidence

advertisement

Making the most of prisons research: an appreciative inquiry Alison Liebling Cambridge Institute of Criminology Prisons Research Centre 30 September 2013 Questions What is a Prisons Research Centre (or a Global Centre for Evidence-Based Corrections and Sentencing Research)? What is a Prisons Research Centre for ..? (‘Grow a generation of highly competent prisons research scholars’); quality and outcomes What does good prisons research look like? What ‘goes on..’ on a good research day? What sorts of structural, intellectual and organisational arrangements support good research? What is the (vital) role of PhD students? How does research become cumulative? What has worked for us… ‘This is high-risk research. We want an exploratory piece of work. We don’t want mechanical research. We don’t like the designs we have seen. We want to know, have we got a problem, and if so, what sort of problem? We want someone like you to do it. Your kind of thinking and previous work.’ (MOJ). Harding’s endorsement: instantly recognisable carefully conducted combined qualitative/quantitative methodology .. Throughcare, suicide (4), difficult prisoners (2), privatisation (3), staff-prisoner relationships, the work of prison officers, IEP, leadership and faith identity .. Miles Raymond on Pinot Noir (“Sideways”):- Maya: Why are you so in to Pinot?... I mean, it's like a thing with you. Miles Raymond: [laughing softly] Miles Raymond: Uh, I don't know, I don't know. Um, it's a hard grape to grow, as you know. Right? It's uh, it's thin-skinned, temperamental, ripens early. It's, you know, it's not a survivor like Cabernet, which can just grow anywhere and uh, thrive even when it's neglected. No, Pinot needs constant care and attention. You know? And in fact it can only grow in these really specific, little, tucked away corners of the world. And, and only the most patient and nurturing of growers can do it, really. Only somebody who really takes the time to understand Pinot's potential can then coax it into its fullest expression. Then, I mean, oh its flavors, they're just the most haunting and brilliant and thrilling and subtle and... ancient on the planet. Appreciative Inquiry Discovers what is life affirming in indiv/organisation Exceptional but real experiences: the positive core of experience ‘Tell me about an aspect of yourself, or your life that you are most proud of..’ ‘What is the most rewarding experience you have had since coming here?’ ‘Tell me about the most positive experience you have had with a member of staff since coming here…’ Builds trust. ‘Asking such questions, in the darkest places, can “significantly influence the destiny of our social theory ..”’ (Ludema et al 2001; Liebling, forthcoming) The unconditional positive question ‘ignites transformative dialogue and action’, and enriches understanding. Builds ‘grounded generative theory’, language of possibility. 6 Some models: e.g. Richard Sparks and Will Hay Doing time in Wakefield, Albany Long Lartin Sparks, Bottoms and Hay (1996) Prisons and the Problem of Order A sociologically imaginative exploration A dialogic model Outcome: changes of perspective and selfunderstandings Operationalisation and quantification follows later .. (legitimacy and order/well-being) 7 Qu: What research (or piece of writing) has most helped you in your professional practice? Does anything in particular stand out? the original Whitemoor work on the work of prison officers Sarah Tait’s work on care in prison officers Prisons and their moral performance Various suicide prevention studies Charles Elliott’s work on AI and change management Our work on values and practices in leadership Shadd/Fergus’ work on desistance (‘Desistance theory now underpins everything we do’; Senior manager) ‘The fact that we systematically, through MQPL, ask prisoners whether they feel they have been treated with kindness seems to me to be hugely symbolic both of the way we still seek to manage prisons and a historic willingness to apply research 8 intelligently to that task’. (Senior manager) Good prisons research ‘Good research is getting as close as you can to understanding, describing and explaining the experience of others/the organisation without anyone getting hurt’. 9 And finally… some questions: What are the most important research questions? what kinds of relationships should good prison scholars have with the field, with gatekeepers, and the consumers of research? Who are the key consumers of research? What grows professional trust? Are there ways in which the funding or organisation and management of prisons research could secure more of the most useful and insightful variety? What would a ‘best’ future prisons research agenda look like? There are identifiable aspects of prison life and quality that differ significantly and that promote or impede personal development or human flourishing. Personal development is a meaningful goal for prisons to pursue. It is not easily achievable. It is possible that increased personal development might build resilience against fundamentalist or extremist belief systems as well as reduce the risk of offending in general, and prison suicide. It is important to define, operationalise and test the concept of personal development (or human flourishing) and what supports it more precisely. A risk-based penal system is unlikely to support personal development, as risk management strategies tend to communicate disrespectfully and negatively about the offender’s ‘being’, to be past-centred rather than futureoriented and to constrain potentially important relationships with change agents. And in the community…? 11 ‘Transformation’ effects of imprisonment Suicide Disorder Reoffending Radicalisation psychological survival a reduction in the risk of harm to others improved mental health or well-being; resilience to extremist ideologies linked to violence. 12 The more damaging prisons in each case share certain characteristics: Disorganised Staff are resistant to positive work with offenders (and often in conflict) Regimes are impoverished The culture is indifferent or worse. Fear (among both staff and prisoners) and violence. Preoccupations with safety and survival dominate; Opportunities are few 13 Negative emotional states are common. Revised dimensions measuring the moral quality of prison life (Liebling, Crewe and Hulley 2011) Harmony Entry into custody Respect/courtesy Staff-Prisoner relationships Humanity Decency Care for the vulnerable Help and assistance Professionalism Staff professionalism Bureaucratic legitimacy Fairness Organisation and consistency Security Policing and security Prisoner safety [Prisoner adaptation] [Drugs and exploitation] Conditions and Family Contact Regime decency Family contact Wellbeing and Development Personal development Personal autonomy Wellbeing 14 The distinctive characteristics of our study (ethnography-led measurement) are: (i) the prisoner-led identification of the dimensions and wording of the items; (ii) the cumulative nature of the work and its grounding in specific investigations of outcomes such as suicide; iii) the taking into account of contemporary developments in the prison experience; iv) an emphasis on good uses of power, and the operationalisation of this, rather than an exclusive focus on quantity v) an avoidance of any reliance upon official statistics; and vi) our work does not have its origins in psychiatric treatment or management studies but is primarily sociological. 15 A – ‘Poor’ B – ‘Average’ C – ‘Good’ D – ‘Very Good’ Private Trainer Private Trainer Private Local Public Local Public Trainer Private Trainer Private Local Dovegate Rye Hill Forest Bank Bullingdon Garth Lowdham Grange Altcourse Respect/ courtesy 3.01 Prisoner safety 3.24 Respect/ courtesy 3.07 Care for the vulnerable 3.01 Prisoner safety 3.32 Drugs and exploitation 3.02 Respect/ courtesy 3.18 Staff-prisoner relationships 3.10 Care for the vulnerable 3.10 Staff professionalism 3.18 Prisoner safety 3.32 Respect/ courtesy 3.24 Staff-prisoner relationships 3.15 Care for the vulnerable 3.27 Help and assistance 3.22 Staff professionalism 3.24 Policing and security 3.35 Prisoner safety 3.46 Respect/ courtesy 3.29 Staff-prisoner relationships 3.17 Humanity 3.08 Care for the vulnerable 3.15 Help and assistance 3.05 Staff professionalism 3.25 Policing and security 3.26 Prisoner safety 3.36 Personal development 3.04 Personal autonomy 3.04 Entry into custody 3.21 Respect/courtesy 3.47 Staff-prisoner relationships 3.27 Humanity 3.17 Decency 3.30 Care for the vulnerable 3.24 Help and assistance 3.20 Staff professionalism 3.27 Policing and security 3.22 Prisoner safety 3.57 Drugs and exploitation 3.22 Personal development 3.07 Personal autonomy 3.14 Wellbeing 3.19 Entry into custody 3.10 Respect/courtesy 3.48 Staff-prisoner relationships 3.45 Humanity 3.27 Decency 3.38 Care for the vulnerable 3.44 Help and assistance 3.37 Staff professionalism 3.53 Fairness 3.15 Organisation and consistency 3.08 Policing and security 3.27 Prisoner safety 3.48 Personal development 3.28 Personal autonomy 3.22 Wellbeing 3.07 Personal Development (α = .875). An environment that helps prisoners with offending behaviour, preparation for release and the development of their potential. Item no rq25 rq87 rq17 rq146 rq133 rq114 rq46 qq65 Item Corr. My needs are being addressed in this prison. I am encouraged to work towards goals/targets in this prison. I am being helped to lead a law-abiding life on release in the community. Every effort is made by this prison to stop offenders committing offences on release from custody. The regime in this prison is constructive. My time here seems like a chance to change. This regime encourages me to think about and plan for my release. On the whole I am doing time rather than using time. (removal α = .877) .690 .689 .683 .660 .650 .655 .592 .477 17 Dimensions with the most significant variation between prisons Staff professionalism (p) Organisation and consistency) (p) Staff-prisoner relationships (h) Fairness Decency Help and assistance (h) Bureaucratic legitimacy (p) Well being (w) Personal development (w) 2.62 - 3.53 .91 2.23 - 3.08 .85 2.74 - 3.45 .71 2.46 - 3.15 .69 2.72 – 3.38 .66 2.74 - 3.37 .63 2.35 - 3.97 .62 2.57 – 3.19 .62 2.69 – 3.28 .59 Figure 4. Personal Development: An in-prison model 1 BUREAUCRATIC LEGITIMACY HUMANITY ‘THE TRANSPARENCY AND RESPONSIVITY OF THE PRISON/PRISON SYSTEM AND ITS MORAL RECOGNITION OF THE INDIVIDUAL’ (3.97) ‘AN ENVIRONMENT CHARACTERISED BY KIND REGARD AND CONCERN FOR THE PERSON’ .144 *** (3.27) .166 *** STAFF PROFESSIONALISM ‘STAFF CONFIDENCE AND COMPETENCE IN THE USE OF AUTHORITY’ PERSONAL DEVELOPMENT (‘HELP WITH THE DEVELOPMENT OF POTENTIAL’) .145 *** (3.53) R2 = 69.2 (3.28) HELP AND ASSISTANCE ‘SUPPORT AND ENCOURAGEMENT FOR PROBLEMS, INCLUDING DRUGS, HEALTHCARE + PROGRESSION’ .413 *** .101 *** (3.37) ORGANISATION + CONSISTENCY ‘THE CLARITY, PREDICTABILITY AND RELIABILITY OF THE PRISON’ (3.08) 19 1 Controlling for function, + public/private ownership/management Further reading Liebling, A (2013) ‘Legitimacy under pressure’ in high security prisons in J. Tankebe and A. Liebling (eds) Legitimacy and Criminal Justice Oxford: Oxford University Press, in press. Liebling, A; assisted by Arnold, H (2004) Prisons and their Moral Performance: A Study of Values, Quality and Prison Life Oxford: Clarendon Press. Liebling, A., Hulley, S. and Crewe, B. (2011), ‘Conceptualising and Measuring the Quality of Prison Life’, in Gadd, D., Karstedt, S. and Messner, S. (eds.) The Sage Handbook of Criminological Research Methods. London: Sage. Hulley, S., Liebling, A., and Crewe, B. (2012) 'Respect in prisons: Prisoners’ experiences of respect in public and private sector prisons', Criminology and Criminal Justice, 12 (1), 3-23. Liebling, A., Arnold, H and Straub, C (2012) An Exploration of Staff-Prisoner Relationships at HMP Whitemoor: Twelve Years On, London: National Offender Management Service Liebling, A Tait, S (2005) ‘Revisiting prison suicide: the role of fairness and distress’, in A Liebling and S Maruna 20 (eds) The Effects of Imprisonment Willan