Māori children and asthma - Asthma Foundation New Zealand

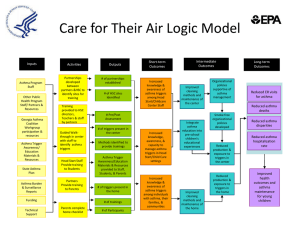

advertisement

Maori Children with Asthma Presented by Sue Armstrong RN BN PG Cert Introduction “Asthma affects Maori disproportionately to other children in New Zealand” (Best Practice Journal, 2008, p. 2). •Contributing factors •Focus on Te Whare Tapa Wha •Nurses recognise the specific needs •Healthcare appropriate & effective •Nurse-led clinics •Role of Asthma Nurse in Primary Healthcare Maori Health Status •NZ has highest rate of childhood asthma:1 in 4 •Greater prevalence in Maori children •More days off school • Presenting with more severe asthma •Maori 2-3 times more likely to be hospitalised •Death from asthma uncommon / preventable – Maori 4 x more likely to die (Ministry of Health, 2010) Barriers to Healthcare •Socio economic– affordability housing and education •Inadequate Access •Lack of Asthma education •Illness perception •Household priorities (Buetow, Richards et al, 2004) (Cram, Smith & johnstone, 2003) •Past bad experiences (Ellison-Loschmann, Gray, Cheng & Pearce, 2008) Risk Factors Environmental Exposure to second hand smoke greater disease severity (Neogi & Neher, 2012) Smoking most prevalent in Maori popn •Half of Maori smoke, 60% women •Maori 2 x more likely to smoke inside house (Ash, 2012) • Damp / cold housing (Etzel,2003) Non-adherence with preventer medications (Seeleman, Stronks, Van , Aalderen & Bot, 2012) Disparities in Clinical Care •Lower rate of ‘easy to understand education / action plans •Less likely to have regular GP • Less likely to receive ICS / Rx not collected •Maori children more likely to not have action plan / spacer/ PF meter (Best Practice Journal, 2008) (Ministry of Health, 2012) Spiritual has very broad meaning Here we use it as a sense of identity and place. (Cram, Smith & Johnstone, 2003) Improved asthma management allows the child to feel a sense of well-being. Best Practice Journal, 2008) Reflects on the emotional toll that comes from having serious and a potentially life threatening illness. The level of emotional support in responding to such a health risk can play a significant part in the outcome (Cram, Smith & Johnstone, 2003) Improved asthma management gives confidence to the child and whanau for managing future asthma exacerbations and relieves anxiety. (Best Practice Journal, 2008) Reflects the need to prevent exposure to the physical risks. Promoting smoking cessation & warm housing. (Cram, Smith & Johnstone, 2003) Improved asthma management increases the ability of the child to participate in physical activities. ie. Playing with other children. (Best Practice Journal, 2008) Prevention education such as medication adherence are far less likely to succeed if they are done individually. By taking into account the family or social environment there is a greater likelihood of success. Given the genetic links of asthma it is likely that asthma clusters in families so identification of the development in one individual should encourage screening and prevention programmes to the family as a matter of good practice. (Cram, Smith & Johnstone, 2003) Improved asthma management results in less distress for the family and can also result in more participation in family activities. (Best Practice Journal, 2008) Role of the Nurse Large role to play in reducing barriers Unique position providing 80% of direct care Role of advocating for patients becoming ‘defender and promoter’ Eg. Questioning Drs as to why pt not on a preventer providing recommendations Eg. Referring pt on to appropriate services Practising opportunistic nursing The need to perform critical self-reflections on personal practice - identify and resolves attitudes that put Maori at risk of cultural harm (Smye, Josewski & Kendall, 2010 cited in Theunissen, 2011). Nurse-led Clinics Nurse-led interventions are the MOST suitable (Theunissen, 2011) NZ studies shown benefits of clinics in increase patient satisfaction, improved patient education & health outcomes (Manson, 2012) Asthma education critical to effective self management Dedicated time with clients to build rapport Te Whare Tapa Wha - Discuss social issues affecting whanau, smoking cessation, transport issues, housing concerns Kaipara Asthma Nurse MOH funded – free Strong education focus / interactive •Asthma assessments - recommendations •Booked appointments / opportunistic / School visits / Te Ha/ Public Health nurses RAPPORT -key facilitator of Maori access to Healthcare. (Cram, Smith & Johnstone, 2003) Smoking cessation Healthy Homes Transport – health shuttle Tyrone Nana 12yr old Youngest of 6 Abusive home / low self esteem New to Dargaville Living with Grandparents 55 yr old Cx / CVD nurse Smoking cessation programme Health shuttle Te Ha services Preventer Meds Flu vaccine Self management / Action Plan Healthy Homes Programme IMMS updated Smoking education Tyrone’s cousin School visit Social Worker Male mentoring programme 10yr old Asthma assessment / IMMS Preventer meds Auntie 45 yr old Smoking cessation programme Referral for spirometry Conclusion •Barriers & risks factors identified •Te Whare Tapa Wha widely recognised •Nursing role / Nurse led clinics crucial Be kind Be clear Be loyal Keep promises and Say sorry Ash, action on smoking and health. (2012). Maori smoking. Retrieved from http://www.ash.org.nz/site_resources/library/Factsheets/09_Maori_sm oking_ASH_NZ_factsheet.pdf Asthma and chronic cough in Maori children. (2008). Best Practice Journal, 13, 20-24. Buetow, S., Richards, D., Mitchell, E., Gribben, B., Adair, V., Coster, G. & Hight, M. (2004). Attendance for general practitioner asthma care by children with moderate to severe asthma in Auckland, New Zealand. Social Science & Medicine, 59, 1831-1842. Doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.02.025 Cram, F., Smith, L. & Johnstone, W. (2003). Mapping the themes of Maori talk about health. The New Zealand Medical Journal, 116 (1170) 1-7. Ellison-Loschmann, L., Gray, M., Cheng, S & Pearce, N. (2008). Asthma severity in Maori adolescents. Australasian Epidemiologist, 15(2) 4-10. Etzel, R. (2003). How environmental exposures influence the development and exacerbation of asthma . Pediatrics. 112(1) 236-239. Inequalities in asthma prevalence, morbidity and mortality. (2008). Best Practice Journal: Special Edition, 2-3. Manson, L. (2012). Racism compromises Maori Health. Kai Tiaki Nursing New Zealand,18(3)30. Ministry of Health. (2012) Maori health models. Retrieved from http://www.health.govt.nz/our-work/populations/maorihealth/maori-health-models Ministry of Health, (2010). Tatau Kahukura: Māori Health Chart Book 2010 ( 2nd ed.). Retrieved from http://www.health.govt.nz/publication/tataukahukura-maori-health-chart-book-2010-2nd-edition Neogi, T., Safranek, S. & Kelsberg, G. ( 2012). How does smoking in the home affect children with asthma? The Journal of Family Practice, 61(5), 292-293 Practical solutions for improving Maori health. (2008). Best Practice Journal, 13, 10-14. Seeleman, C., Stronks, K., van Aalderen, W. & Essink Bot, M. (2012). Deficiencies in culturally competent asthma care for ethnic minority children: a qualitative assessment among care providers. BMC Pediatrics, 12(47) 1-8. doi:10.1186/1471-2431-12-47 Theunissen, K. (2011). The nurse’s role in improving health disparities experienced by the indigenous Maori of New Zealand. Contemporary Nurse: A Journal For The Australian Nursing Profession, 39(2), 281-286.