Learning objectives

Describe pre-1980s concept of masculinity

Describe concept of multiple masculinities

Understand how generalized notions of masculinity (and,

by extension, femininity) are problematic

Describe how boys learn masculinity through socialization

Describe how gender affects power/position in society

Infer how feminism and masculinity studies interact

Masculinity pre-1980s

Prior to the 1980s, masculinity and femininity were often

considered tied to one’s physical sex.

Masculinity and femininity were seen as personality traits

and behaviors and were associated with sex roles.

What was left out

of the pre-1980s discussions?

Discussion of power and subordination in gender roles

What men actually do in groups and as individuals that

helps them identify as men

Plurality & its problems

Definitions as used by Schrok and Schwalbe:

Male—biological state based on reproductive anatomy.

Men—Males who claim rights and privileges of the “dominant gender group.”

Masculinity—the individual’s self-concept as male and the signification of that

possession.

Post-1980s, scholars began to describe specific versions of

masculinity—i.e., black, Jewish, working-class, and gay. While

this moved the concept of masculinity and manhood away from a

singular model (usually white middle class heterosexual males), it

still described male experience within the various groups in

generalized terms and didn’t accommodate the actual diversity of

male experience (i.e. a gay man with multi-racial roots).

Signifying the

masculine self

Socialization of roles starts with external affirmations—for

example, adults praising “big boy” behavior in toddlers.

Parents, teachers, and peers reinforce gender roles—boys

are directed toward trucks and clothes designed for boys.

The boy who experiments with nail polish is scolded or

teased.

By elementary school, boys and girls self-segregate or, when

playing together, boys often engage in play that emphasizes

the difference between boys and girls and an assumed

superiority of boys over girls—e.g., a game of dodge ball

where physical power and speed are essential.

Signifying the

masculine self

Young males learn to control their emotions, a behavior that is

enforced by both peers and parents. For example, boys who cry

are ostracized by peers.

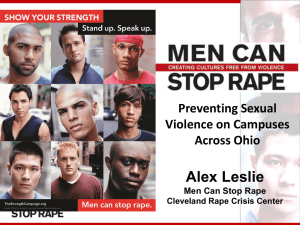

Boys and young men are encouraged to present themselves as

aggressively heterosexual. They use homophobic taunting to

regulate each other’s behavior.

Aggression and violence is admired in males; young boys may

express this in imaginative “good vs. evil” play.

Males learn to read and play to an audience’s expectations of them

as men—i.e., a physical laborer who prides himself on strength,

endurance, and resistance to being bossed around.

Learning from the Media

Boys in elementary school may concentrate on superheroes.

In middle school, boys may switch to discussing and

emulating male heroes in movies.

Power is glorified in children’s media designed for boys.

Media aimed at adolescent and young men often roots

manhood in a voracious heterosexual appetite, work, and

hypermasculine bodies.

Media also tends to idealize the white heterosexual monied

man. Men of other backgrounds or groups are marginalized

in mainstream media.

Manhood Acts

Research on transsexuals—particularly the female-to-male—

showed that when biological females adopt the gestures,

clothing, and mannerisms of males, they often gain social

power (especially if they present themselves as traditional

heterosexual men and happen to be white).

Middle- and upper-class men often invoke their position as

the family provider to avoid childcare and housework.

Even in lower-class households, men use strategies such as

violence to maintain control of the relationship; men of all

classes may use emotional withdrawal as a form of control.

Manhood acts

In the workplace, men in management may use a

paternalistic demeanor or strive to show rationality, resolve,

and competitiveness.

Men in lower positions may assert their masculinity by

refusing to be bossed around.

Women are sexualized as a way to assert male

heterosexuality, both to maintain power and to avoid being

abused by peers.

Openly gay men may value muscularity and macho fashion

as a way to retain a position of power that does not rely on

sexuality.

Reproducing gender

inequality

In traditional expression of masculinity, men strive to show

a capacity for exerting control over self, the environment,

and other people.

Manhood acts are how men distinguish themselves from

women, establishing their eligibility for gender-based

privilege.

The hegemonic ideal may serve men in the workplace as

they seek promotion and privileges afforded to men.

In political and social realms, men benefit from appearing to

conform to the hegemonic ideal of masculinity.

Suggestions for research

Manhood acts can be detrimental to men as high-risk

behaviors put them at higher risk of death, suicide, or to be

without social and emotional support.

Research needs to make distinctions between anatomy, sex,

and gender categories.

Studying how manhood acts are institutionalized may shed

light on how men collaborate to construct masculinity in

changing times.

Discussion ideas

How does the digital age change manhood? For example, do

social networks or online gaming change how young men

collaborate and regulate each other’s behavior?

How can we discuss masculinity in terms that don’t automatically

negate the feminine? For example, why does “male” or

“masculine” often automatically equal “not-female” (i.e., using

phrases like “you throw like a girl” or “he cried like a little school

girl” to belittle a man)?

In the four years since this article was originally published, we

have seen more diverse visions of masculinity in mainstream pop

culture. In what ways has this changed the definition of

“manhood” and “manhood acts” as used by the authors?