How did this all come about?

The first British novel was published in 1719 =

Robinson Crusoe by Daniel Defoe

As a new invention, these novelists

experimented with form and content.

Epistolary

structure

Amorous & Gothic fiction

Popular but shameful!

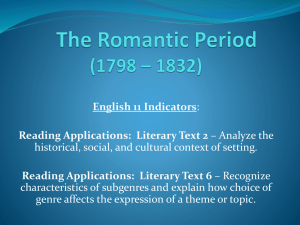

Shift from order and reason to emotion and

imagination

If science explains our existence, where is there

space for feeling, reflection, thinking,

exploration, and emotion?

Romantics believed that science could NOT fully

grasp the essence of “human.”

“head vs. heart” OR “sense vs. sensibility”

• Jane Austen novel- Sense and Sensibility 1811

Lyrical Ballads- 1798/ Wordsworth & Coleridge

“Big 6”

•

•

•

•

•

•

Shelley

Keats

Byron

Coleridge

Wordsworth

Blake

“Satanic School”- Byron & Shelley

• People saw Romantic writing as morally reproachable!

Past- return to Medieval Times & Knight’s tales

Imagination- what man can create with his mind

that cannot be created with science

Common Man- everyday life/ not just stories

about aristocrats

Idealization of Women- a return to the chivalry of

the Medieval Times

Nature- growing Industrialization & the Industrial

Revolution makes man appreciate nature even

more

Emotion- feelings as more true to the human

experience than scientific formulas

“Gothic

vs. Romantic” by Hume

“Shift

from Neoclassical ideals of order and

reason toward Romantic belief in emotion

and imagination”

Refers

to Burke’s essay on the sublime“‘terror is the author’s principal engine’ to

grip and affect the reader”

“one

of a kind treatment of the

psychological problem of evil”

“the

Gothic form had a curious appeal in

terms of weaving a beauty of the

unpleasant, the horrifying and even

grotesque”

• This had a powerful impact on the human senses

which Romantic fiction was all about.

• Gothic fiction gave way to Romantic fiction

Writers and critics in this period treated

Gothic works like The Castle of Otranto—

at the time, collectively referred to as

“terrorist literature,” for their ability to

induce feelings of horror—both as

objects of scorn, and as (often

unacknowledged) sources of inspiration.

The Gothic was a matter of particular

concern for writers and critics in the late

eighteenth and early nineteenth-centuries

primarily because it was a phenomenally

popular literary genre, particularly for

women readers.

Ex. Catherine Morland in Jane Austen’s

Northanger Abbey hiding The

Mysteries of Udolpho by Anne Radcliffe

One of the most common accusations against the Gothic was that it was

fundamentally immoral: Gothic romances were said to corrupt their readers’ minds

and encourage social disorder. The pedagogical effect of the genre on children was

thought to be especially dangerous. An anonymous critic, who wrote a polemic

against “Terrorist Novel Writing” in The Spirit of the Public Journals for 1797,

denounced the Gothic for illustrating grotesque fantasies that defied the limits of

common sense, claiming that these fantasies were bad moral lessons, which

“carr[y] the young reader’s imagination into such a confusion of terrors, as must be

hurtful. Unlike “useful” novels, which accurately depict “human life and manners,

with a view to direct the conduct in the important duties of life, and to correct its

follies,” Gothic romances illustrate bizarre situations “reaped from the distorted

ideas of lunatics.”

In this critic’s view, Gothic romances were hardly idle enjoyments: they were

insidious implements of chaos that would ruin young people’s capacity for labour

and for public service. This all-too-common “taste for the marvelous and the

terrible” was, as the Monthly Review stated in 1796, akin to a plague, “an infection,”

that must be stamped out for the health of the nation (qtd. in Epstein 205).

The effect of the Gothic on women was thought to be, if anything, even more

frightening. Terrorist fiction was accused of producing a cohort of mannish women,

who would rather dream of death-defying adventures and thrilling romances than

settle down, get married, and attend to their feminine duties.

In the eyes of conservative critics, a whole generation of women—

and, by extension, a whole generation of wives and mothers, the

very future of England—was in danger of contamination by the

Gothic. The sanctity of matrimony itself was threatened by these

books, which trained women to imagine marriage not as a solemn

union before the watchful eyes of Church and State, but as a

dramatic spectacle, in which bride and groom would pass

“through long and dangerous galleries, where the lights burn

blue, the thunder rattles, and the great window at the end presents

the hideous visage of a murdered man” (“Terrorist” 601). In a

world where women preferred to fantasize about confronting hosts

of ghouls and nightmares with a dashing young man than

marrying the proper gentleman selected for them by their

parents, it was not hard for conservatives to imagine that social

decay was imminent. By “emphasizing power relations and

entaglements, and developing themes of veiling and entrapment,”

the Gothic taught women to do the unthinkable: suspect the men in

their lives—husbands, fathers, and priests—of potentially

harbouring malevolent intentions towards them (Epstein 205).

Gothic romances were disparaged not only for filling women’s

heads with impossible dreams and potentially turning females

against their male rulers, but also for touting profligacy and

indolence.

Anyone wanting to make a quick dollar

could successfully write a bestselling

Gothic romance. Gothic authors were

accused of being less artists than

manufacturers, less writers than druggists

following pre-made prescriptions, pushing

vast quantities of mass-produced novels

onto the market. The entire genre was

effectively maligned by such attacks as a

bourgeois conspiracy: a secret

moneymaking pact between greedy

booksellers, printers, and hack writers.

Coleridge held a derogatory opinion of Gothic novels. His friend

and literary collaborator William Wordsworth took many

malicious, in-direct snipes at the Gothic in the preface to the

second edition of Lyrical Ballads, the foundational work of English

Romanticism. Wordsworth derided the Gothic—which he

pejoratively foreignized as “frantic novels, sickly and stupid

German tragedies”—for stirring up overly strong, forceful

emotions like terror and despair (Wordsworth 267). In his view,

Gothic novels were textual drugs, which numbed human faculties

of sympathy and imagination, and their devoted readers were

addicts possessed by a “degrading thirst after outrageous

stimulation” (Wordsworth 267). The genre employed a plethora of

“gross and violent stimulants,” which obscured, rather than

revealed, the nature of reality (Wordsworth 266). Stylistically, the

Gothic was overwrought in its prose and melodramatic in its

themes, littered with “gaudiness and inane phraseology”

(Wordsworth 264). In many respects, Wordsworth theorized what

he and Coleridge were doing in their poems—i.e. using

unadorned, simple language to meditate “in tranquility” upon

powerful emotions that were experienced by ordinary, “rustic”

men and women, and induced by everyday situations in nature—

as the polar opposite of the Gothic. Romantic poetry was akin to a

twelve-step program for weaning society off its addiction to

extravagant Gothic romances.

What Romantic and Gothic literature share is a belief that the chief

role of literature should be to arouse and channel primal human

affects and emotions like fear, wonder and eroticism. Such

sentiments are powerful and potentially transgressive, having the

capacity to unsettle rigid hierarchical social divisions, which is

why both Gothic and Romantic authors were, at times, considered

deviant by England’s establishment. While Gothic works like The

Castle of Otranto, which are notorious for having wooden, stock

characters and predictable situations, focus on surfaces,

externalities and seemingly superficial details, Romantic works

tend to focus on depths—the rich, lively, complex depths of the

natural world and the human psyche in particular. We can interpret

the Gothic, and all of the complicated responses to it, as the

symptoms of a society struggling to think through the implications

of a great many significant changes: changes in the extent and

meaning of literacy, and changes in how humans understand their

own lives and the lives of people around them.

1764

Generally

regarded as the first Gothic

novel ever written

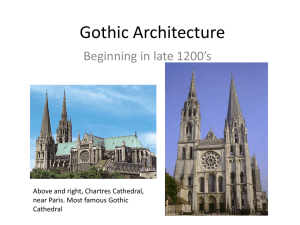

Built a home called Strawberry Hill in the

classic Gothic architecture before his

Victorian successors would adopt the

style