Neighborhoods and Health

POPULATION RESEARCH SEMINAR SERIES

Sponsored by the Statistics and Survey Methods Core of the U54 Partnership

Neighborhoods and Health

Reginald Tucker-Seeley, ScD

Assistant Professor of Social and Behavioral Sciences

Center for Community Based Research, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute/

Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences, Harvard School of Public Health

Overview

• Background

• Challenges to research on the association between neighborhoods and health

• Interventions at the neighborhood level

– Intervening on the residents

– Intervening on the place/space

– Intervening on the residents and the place/space

• Summary/Conclusions

Background

• Where we live matters

Background

• Characteristics of places associated with health/health behavior:

– Safety (Tucker-Seeley, et al. 2009; Bennett, et al.

2007)

– Aesthetics (Hoehner, et al. 2005)

– Physical structure (Brownson, et al. 2009)

– Food stores (Sharkey, et al. 2009)

Background

• Proximity and the density of liquor stores associated with health behavior and health status of residents (Cunradi, 2010; Romley, et al, 2007; LaVeist et al, 2000)

• Association between minority concentration, alcohol outlet density, and alcohol problems

(Alaniz, 1998)

Source: RWJF Commission to Build a Healthier America, Where we live matters to our health

What is a neighborhood?

• Block(s)

• Administrative boundary (e.g. census)

• Area between natural/man-made barriers

What is a neighborhood?

What is a neighborhood?

Neighborhood Definition

• The definition of “neighborhoods” is a difficult one to capture; as “neighborhoods” have emergent properties that are created and defined both by larger structural forces AND by the residents within them.

Neighborhood Definition

(Sampson, 2012)

• Neighborhoods are “spatial units with variable organizational features, and…are nested within..larger communities. Neighborhoods vary in size and complexity depending on the social phenomenon under study and the ecological structure of the larger community.”

(Sampson, 2012, pg. 54).

What is a “good” neighborhood?

• Safe to walk to destinations

• Aesthetically pleasing (attractive features, well-maintained buildings)

• Trust fellow neighbors

• Can count on neighborhoods to help keep neighborhood well-maintained

• Stable/long-term residents

What is a “bad” neighborhood?

• Not safe (fearful of crime)

• Transient residents

• Dilapidated buildings

• Unfavorable retail

– liquor stores

– alternative financial institutions (check cashers, pawn shops)

– Empty storefronts

Neighborhood environment

• Where we live matters

– Quality of the neighborhood environment influences health and health behavior

– Safety

– Aesthetics

– Physical structure

• Neighborhood service environment

– What are the options available to the residents for services?

– Are there specific mixes of services associated with resident behavior?

– Is the current mix of services what the residents want?

Sampson (2012)

• “What happens in one neighborhood is tightly connected to adjacent neighborhoods, creating a “ripplelike” effect that encompasses the entire city.”

Neighborhood Boundaries

• Perceived “neighborhood” boundaries may vary between residents in an area (Coulton, et al, 2013)

• Different neighborhood sizes used in research may work differently across variables and behaviors (Lee and Moudon, 2006)

• “the effects of area-based attributes could be affected by how contextual units or neighborhoods are geographically delineated and the extent to which these areal units deviate from the true causally relevant geographic context” (Kwan, 2012)

Neighborhoods and Health Theory

• No widely accepted theory that clearly outlines constructs, describes mechanisms and links to health behavior/health

– Ross (2000) hypothesizes that neighborhoods can affect behavior through a contagion mechanism where people’s behavior is influenced by those around them and a structural mechanism where neighborhood environments organize the opportunities and resources available to the residents that can influence health behavior.

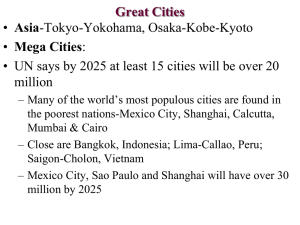

Sampson (2012)

• “How do individual choices combine to create social contexts that then constrain choices?”

– At multiple levels

– How do we capture the individual choices and social contexts and their influence on constrained choices in our theories and methods?

Model of the influence of neighborhood and individual level resources on health

Residential segregation by race/ethnicity and socioeconomic position

Neighborhood physical environments

Environmental exposures

Food and recreational resources

Built environment

Aesthetic quality/natural spaces

Services

Quality of housing

Behavioral mediators

Stress

Inequalities in resource distribution

Neighborhood social environments

Safety/violence

Social connections/cohesion

Local institutions

Norms

Health

Personal Characteristics

Material resources

Psychosocial resources

Biological attributes

Source: Diez-Roux and Mair, 2010

Model of the influence of neighborhood and individual level resources on health

City level policies

•Zoning

Historical housing/ mortgage practices

•“Redlining”

Residential segregation by race/ethnicity and socioeconomic position

Neighborhood physical environments

Environmental exposures

Food and recreational resources

Built environment

Aesthetic quality/natural spaces

Services

Quality of housing

Behavioral mediators

Stress

Inequalities in resource distribution

Neighborhood social environments

Safety/violence

Social connections/cohesion

Local institutions

Norms

Health

Personal Characteristics

Material resources

Psychosocial resources

Biological attributes

Source: Diez-Roux and Mair, 2010

Model of the influence of neighborhood environment

Neighborhood

Environment

• Land Use

• Public services

• Health care resources

• Financial

Resources

• Retail/Commercial

Experience of the

Neighborhood

• Attachment

• Sense of Community

• Feeling of relegation

• Residential captivity

• Internalized Stigma

• Perceived Safety

Psychological

Well-Being

• Stress

• Anxiety

• Depressive

Symptoms

Social Cognitive

Factors

• Life Values

• Knowledge/beliefs

• Self-esteem

• Self-efficacy

• Locus of Control

Health Behaviors

• Physical activity o

Recreation o

Transportation

• Diet

• Smoking

• Alcohol

Consumption

• Health care utilization

Other Risk Factors

• Obesity

Based on Chaix, 2009

What do we really mean by

“neighborhood effects”?

• What are “neighborhood/place effects” really capturing?

Segregation and Place

“The research literature documents that “places” which are racially segregated with high concentrations of blacks or Hispanics tend to be places with limited opportunities and failing infrastructure, resulting from a lack of investment in social and economic development. The result is a community that produces bad health outcomes. So, racial inequalities in health status and outcomes are predominantly the result of place. Race helps to determine place, and in turn, place influences health.”

(Segregated Spaces, Risky Places: The Effects of Racial

Segregation on Health Inequalities by the Joint Center for Political and

Economic Studies)

Methodological challenge

• Selection bias

– “the selection issue (the fact that persons may be selected into neighborhoods based on individual attributes which are themselves related to health) is the key problem in observational studies of neighborhood effects.” (Diez-

Roux, 2004)

– “the ‘‘selection’’ of people to neighborhoods induces systematic difference in the background composition of residents across neighborhoods” (Oakes,

2004)

Selection

• Explicating the sorting process is [should be] an important aspect of research on neighborhoods and health

– “Selection bias in neighborhood effects research is more than a statistical error and…understanding selection into and out of neighborhoods is at the heart of understanding neighborhood effects.”

(Hedman and van Ham, 2012)

Interventions

• Focused on moving residents out of disadvantaged neighborhoods

– Moving to Opportunity (MTO) Demonstration Project:

“Households chosen for the demonstration's experimental group receive housing counseling and vouchers for rental housing in areas with less than 10 percent poverty.”

Source: http://portal.hud.gov/hudportal/HUD?src=/programdes cription/mto www.mtoresearch.org

Interventions

• Moving residents out of disadvantaged neighborhoods

– What about the residents left behind?

– What about the neighborhoods the residents leave?

Interventions

• Focused on changing the place

– Increased physical activity after walking path and playground installed (Gustat et al, 2012)

Interventions

• Focused on residents and the place

– RESIDential Environments (RESIDE) Project (Perth,

Australia) (Foster, et al, 2013)

• Residents relocated to new housing developments across Perth. New areas designed to create safe, pedestrian friendly neighborhoods.

Summary/Conclusion

• Disparities in health are complex

– With individual level and contextual determinants

• Research on the association between the neighborhood environment and health and interventions at the neighborhood level is complex

References

1. Tucker-Seeley RD, Subramanian SV, Li Y, Sorensen G. Neighborhood

Safety, Socioeconomic Status, and Physical Activity in Older Adults. Am J

Prev Med 2009;37(3):207-213.

2. Bennett GG, McNeill LH, Wolin KY, Duncan DT, Puleo E, Emmons KM.

Safe to walk? Neighborhood safety and physical activity among public housing residents. PLoS Med 2007;4(10):1599-1606.

3. Brownson RC, Hoehner CM, Day K, Forsyth A, Sallis JF. Measuring the built environment for physical activity: state of the science. Am J Prev Med

2009;36(4 Suppl):S99-123.

4. Sharkey JR, Horel S, Han D, Huber JC, Jr. Association between neighborhood need and spatial access to food stores and fast food restaurants in neighborhoods of colonias. Int J Health Geogr 2009;8:9.

5. Cunradi CB. Neighborhoods, alcohol outlets and intimate partner violence: addressing research gaps in explanatory mechanisms. Int J

Environ Res Public Health 2010;7(3):799-813.

References

6. Romley JA, Cohen D, Ringel J, Sturm R. Alcohol and environmental justice: the density of liquor stores and bars in urban neighborhoods in the United States. J Stud Alcohol Drugs

2007;68(1):48-55.

7. LaVeist TA, Wallace JM, Jr. Health risk and inequitable distribution of liquor stores in African American neighborhood. Soc

Sci Med 2000;51(4):613-617.

8. Alaniz ML. Alcohol availability and targeted advertising in racial/ethnic minority communities. Alcohol Health Res World

1998;22(4):286-289.

9. Sampson RJ. Great American City: Chicago and the Enduring

Neighborhood Effect. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 2012.

10. Coulton CJ, Jennings MZ, Chan T. How big is my neighborhood?

Individual and contextual effects on perceptions of neighborhood scale. Am J Community Psychol 2013;51(1-2):140-150.

References

11. Lee C, Moudon AV, Courbois JY. Built environment and behavior: spatial sampling using parcel data. Ann Epidemiol 2006;16(5):387-394.

12. Kwan MP. The uncertain geographic context problem. Annals of the

Association of American Geographers 2012;102(5):958-968.

13. Ross CE. "Walking, exercise, and smoking: Does neighborhood matter? Social science & medicine 2000;51(2):265-274.

14. Diez Roux AV, Mair C. Neighborhoods and health. Ann N Y Acad Sci

2010;1186:125-145.

15. Chaix B. Geographic life environments and coronary heart disease: a literature review, theoretical contributions, methodological updates, and a research agenda. Annu Rev Public Health 2009;30:81-105.

16. LaVeist TA, Gaskin D, Trujillo AJ. Segregated Spaces, Risky Places: The

Effects of Racial Segregation on Health Inequalities. Joint Center for

Political and Economic Studies, 2011

References

17. Diez-Roux AV. Estimating neighborhood health effects: the challenges of causal inference in a complex world. Soc Sci Med 2004;58(10):1953-1960.

18. Oakes JM. The (mis)estimation of neighborhood effects: causal inference for a practicable social epidemiology. Social science & medicine 2004;58(10):1929-

1952.

19. Hedman L, van Ham M. Understanding Neighbourhood Effects: Selection

Bias and Residential Mobility. In: van Ham M, Manley D, Bailey N, Simpson L,

Maclennan D, editors. Neighbourhood Effects Research: New Perspectives.

Springer Netherlands; 2012:79-99.

20. Gustat J, Rice J, Parker KM, Becker AB, Farley TA. Effect of changes to the neighborhood built environment on physical activity in a low-income African

American neighborhood. Prev Chronic Dis 2012;9:E57.

21. Foster S, Wood L, Christian H, Knuiman M, Giles-Corti B. Planning safer suburbs: Do changes in the built environment influence residents' perceptions of crime risk? Soc Sci Med 2013;97:87-94.

POPULATION RESEARCH SEMINAR SERIES

Sponsored by the Statistics and Survey Methods Core of the U54 Partnership