Point of View Powerpoint

advertisement

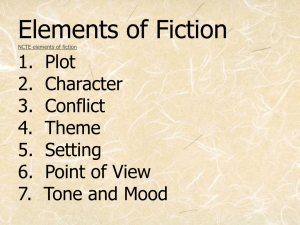

7 Point of View Literature: Craft & Voice Nicholas Delbanco and Alan Cheuse Literature: Craft & Voice | Delbanco and Cheuse | Chapter 7 Point of view refers to the perspective from which a story is told. At the end of Chapter 7 in Literature: Craft & Voice, Nicholas Delbanco and Alan Cheuse outline the numerous points of view from which authors may tell their story. ● First-Person Narrator ● Second-Person Narrator ● Naïve Narrator ● Limited Omniscient Narrator ● Editorial Omniscience ● Interior Monologue ● Third-Person Narrator ● Unreliable Narrator ● Omniscient Narrator ● Objective Point of View ● Impartial Omniscience ● Stream of Consciousness Literature: Craft & Voice | Delbanco and Cheuse | Chapter 7 Point of view is just about everything in fiction. Consider an event or incident that you have witnessed. – In discussions with other eyewitnesses, did versions of the “facts” differ? – Did the other eyewitnesses consider themselves objective? – Did their interpretation of the event or incident depend on their positioning or their vantage point? – Did their interpretation depend on their past experiences and their character? In fiction, as in actuality, the story is shaped by the author’s creation of a narrative voice and the positioning of the voice in relation to the story’s events. Literature: Craft & Voice | Delbanco and Cheuse | Chapter 7 Point of view is just about everything in fiction. Two people, like two characters, can relate the same incident and characterize the same person in entirely different ways with different emphases and details, and therefore different conclusions. When interpreting fiction it is important to identify the narrative voice. Literature: Craft & Voice | Delbanco and Cheuse | Chapter 7 Note the importance of point of view not only to the story “Brownies,” but also to ZZ Packer’s writing process: I found it very good to begin with that [first person] voice because I felt as though I could just tell the story the way I thought that Laurel/Snot would. … And then I put it in third person so that I could see some of my blind spots. This particular third person could see some things about the rest of the world but might not have access to everything that Laurel had access to. So then that allowed me to see beyond Laurel’s point of view. So switching the point of view for me enabled me to get the voice, which I wanted, which was the first person voice, but also to get the knowledge and range of information that sometimes authors can only get when they travel into the third person point of view. ─ Z. Z. Packer Literature: Craft & Voice | Delbanco and Cheuse | Chapter 7 Most Commonly Used Points of View First-Person Narrator – • • • The story is narrated by a character in the story Identified by use of the pronoun I or the plural first-person, we. Consider, for example, Updike’s “A & P” and Faulkner’s “A Rose for Emily.” Third-Person Omniscient – • • • • • A narrator who is outside the story. The narrator refers to all the characters in the story with the pronouns he, she, or they. This narrator observes the thoughts and describes the actions of multiple characters in the story with allknowingness and all-access. This narrator can reveal the characters’ inner most thoughts and emotions and most secretive actions. Consider Malamud’s “The Magic Barrel” and Ha Jin’s “Saboteur.” Third-Person Limited Omniscient Narrator – • • • A third person who enters into the mind of only one character at a time. This narrator serves more as an interpreter than as a source of the main character’s thoughts. Consider Porter’s “The Jilting of Granny Weatherall” and Hawthorne’s “Young Goodman Brown.” Literature: Craft & Voice | Delbanco and Cheuse | Chapter 7 Variations As previously noted, there are other points of view and variations on those just mentioned. Consider, for example the following: The Naïve Narrator – • A narrator, generally unreliable, who is unaware of the full complexity of events in the story, due to youth, innocence, or cultural awareness. • Are the narrators naïve in Mahfouz’s “The Conjuror Made Off with the Dish” and Ellison’s “Battle Royal”? The Unreliable Narrator – • A narrator who cannot be trusted to present an undistorted account of the action because of inexperience, ignorance, personal bias, intentional deceptiveness, or even insanity. • Are the narrators reliable in Poe’s “The Fall of the Usher” and Welty’s “Why I Live at the County P.O”? Are these narrators honest? The Editorial Omniscient Narrator – • A narrator who inserts his or her own commentary about characters or events into the narrative. • Consider the narrator of Tolstoy’s “The Death of Ivan Ilych.” Literature: Craft & Voice | Delbanco and Cheuse | Chapter 7 In this quotation from John Updike, consider how a shift in point of view affects the author’s imagination and the writing process: “Once you break with the first person, then you do discover the wonderful world of multiple view points, and you can fly through space, and go from head to head, and you get out and you become a character in your own right, you become the omniscient author presiding.” ─ John Updike Literature: Craft & Voice | Delbanco and Cheuse | Chapter 7 Point of View in “Brownies” “‘Brownies’ actually started out in the first person point of view,” explains Z. Z. Packer, “and then I changed it to the third person point of view, and then I changed it back to the first person point of view. … The first [person] can oftentimes be the most personal point of view that a writer can employ, but it’s also deceptively simple.” The narrator of “Brownies,” Laurel but called Snot, looks back at a trip to camp when she was in the fourth grade and when she and her African-American brownie troop were almost pressured into a fight with another troop of white, mentally disabled campers. Packer uses a somewhat common but complex perspective. The narrative voice is that of a mature woman remembering and depicting her awareness and sensibilities as a nine-year old. Consider how this perspective shapes the telling of the story. How would the story be different if it were told by a nine-year old who experienced the events only a few weeks or months ago? Would the observations be different? Would the vocabulary change? Would the tone be different? Literature: Craft & Voice | Delbanco and Cheuse | Chapter 7 “Brownies” continued … The slightest shift in point of view has significant implications on the telling of the story Packer, for instance, has her adult narrator withhold information from the reader, not to simply set up a surprise ending but rather to present the consciousness of a child at a pivotal event in her life. We are not told, for instance, of the disability of the white girls until the climax. Until then, the reader and the narrator only see them “from afar,” and we are “never within their orbit enough to see whether their faces were the way all white girls appeared on TV.” As a result, the reader can more fully experience the dramatic impact this experience had on the narrator, as Laurel begins to consider the complexity of life, specifically racial relations, her father’s bitterness, authority and submission, and her own humanity. Other stories in Literature: Craft & Voice use this same perspective. Compare Packer’s use of this technique with that of Alice Munro’s in “An Ounce of Cure,” Amy Tan’s in “Two Kinds,” and James Joyce’s in “Araby.” Literature: Craft & Voice | Delbanco and Cheuse | Chapter 7 Point of View in “The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber” Ernest Hemingway makes judicious use of the third-person limited omniscient point of view in “The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber.” We can argue that the story’s power results from his crafty use of this perspective. Hemingway looks mostly into the consciousness of Robert Wilson. His unspoken thoughts on American men and women, for instance, and his seemingly endless calculating make him a fascinating figure. Throughout the story, we watch Wilson restrain himself in conversation. Hemingway also peers into the consciousness of Macomber, so the reader can watch his profound transformation take shape and reveal itself. Consider his thoughts and actions just before the lion hunt: his nervousness during the preceding night as the lion roars, and his nervousness the next morning and while hunting. Then, note his thoughts and actions after he shoots the buffalo: his “drunken elation,” that “in his life he had never felt so good,” that “for the first time in his life he had a feeling of definite elation,” that he felt “a wild unreasonable happiness that he had never known before,” and his “new wealth.” Literature: Craft & Voice | Delbanco and Cheuse | Chapter 7 “Macomber” continued … Hemingway even tells us what the lion is thinking during the hunt, which establishes sympathy for the animal and complicates notions of courage. However, he examines Margot’s inner works to a far lesser extent than the other principal characters – revealing her fear of her husband’s change but not exposing her reason for firing the gun or her thoughts at the end of the story. Through the use of point of view, Hemingway creates a story with action as dramatic internally as externally and gives us an ending with a question and no definitive answer: Did Margot shoot her husband intentionally? Literature: Craft & Voice | Delbanco and Cheuse | Chapter 7 Point of View in “How to Become a Writer Or, Have You Earned This Cliché” Lorrie Moore’s “How to Become a Writer” is about the development of a young girl into a writer. In a way, the narrator writes a kind of advice or “how-to” manual drawing from her own experiences. Like a “how-to” manual, she uses the second-person point of view. The use of a second-person point of view is rare in fiction. Here, it fits the unusual form and content of the story and underscores its theme and the narrator’s quest to establish a unique fictional voice. Moore makes use of non-traditional presentations of plots and finds some humor in what might be called literary pretensions. She develops humor through sentence rhythms, language, tone, and self-deprecation. The conflict might be defined as the narrator against what seems like a continued unsympathetic and unaccepting readership, beginning with her mother, high school teacher, college professor, classmates, and so on, and her fight against literary conventions. Her decision to write in the second person helps establish her commitment to struggle against conventional expectations. She has dedicated herself to becoming a writer and to tolerating discouragement Literature: Craft & Voice | Delbanco and Cheuse | Chapter 7 Hemingway’s Response to the Question Hemingway was asked the question several times and provided contradictory answers: “Francis’ wife hates him because he’s a coward. But when he gets his guts back, she fears him so much she has to kill him – shoots him in the back of the head.” But, another time, he said, “No, I don’t know whether she shot him on purpose any more than you do. I could find out if I asked myself because I invented it and I could go right on inventing. But you have to know where to stop.” This is one of those times when we must trust the tale and our interpretation of the tale, not the teller. Literature: Craft & Voice | Delbanco and Cheuse | Chapter 7 Point of View in “The Yellow Wallpaper” “The Yellow Wallpaper” is written from the perspective of a firstperson narrator. However, is the narrator reliable? Not all of the narrator’s conclusions seem accurate. For instance, she says that the home used to be a “colonial mansion” and her room a nursery. Yet there are “walls and gates that lock” and “separate little houses,” and her room has iron window bars, wall rings, a bed permanently attached to the floor, and gnawed bedposts. It sounds more like a former institution for the psychologically ill. Of course, too, we can question the narrator’s certainty about the woman behind the yellow wallpaper and the group of women creeping around the garden. If we agree that the narrator is unreliable, does this mean that she is dishonest? Although the narrator may lie to her husband about writing, overall, we will agree that she is honest. However, she is emotionally unbalanced, which makes her unreliable. Literature: Craft & Voice | Delbanco and Cheuse | Chapter 7 “How to Become a Writer” continued … Above all, the narrator values originality and a unique voice. She opens her imagination and lets out what might be if not meaningful at least creative situations and unusual plots. Very importantly, she realizes that “writers are merely open, helpless texts with no real understanding of what they have written.” This realization helps her retain her uniqueness. She does not try to analyze her stories and then rewrite them in more conventional ways at the expense of originality. Her originality is revealed in, among other elements, her deadpan tone (which can be humorous, facetious, cynical, sarcastic, and frustrated), her comically bizarre storylines, and the use of the second-person narrative voice. To an extent, the story is a satire on writing classes, writing instructors, and audiences, all of whom, Moore says, might praise an original voice in Melville but discourage an original voice in a young writer. Compare the style of Moore’s “how-to” manual with that of the narrator’s in Junot Diaz’s “How to Date a Browngirl, Backgirl, Whitegirl, or Halfie.” Literature: Craft & Voice | Delbanco and Cheuse | Chapter 7 “Yellow Wallpaper” continued … But what has driven her into a state of neurosis or even psychosis? This question is crucial to understanding the story. When we consider her life, we realize that she has never been permitted to explore her identity and be herself. As a wife in the late nineteenth century, particularly a wife of a physician, she was expected to fulfill certain obligations, which are derived from her husband and his profession. However, these obligations have left her unfulfilled and empty. The narrator’s life is very much like the yellow wallpaper in her room. The wallpaper, like her life, is deteriorating from lack of attention. Furthermore, the pattern of her life has been as vague and disconnected as the pattern in the design of the wallpaper. She promises to follow “that pointless pattern to some sort of a conclusion.” The woman she sees behind the wallpaper represents an image of herself. Like the woman, the narrator is trapped behind a pattern or way of life that someone else (a husband, a culture) has designed for her. Her deepest self and individuality yearn for expression and freedom. Literature: Craft & Voice | Delbanco and Cheuse | Chapter 7 “Yellow Wallpaper” continued … Compare for reliability the narrator in “The Yellow Wallpaper” and the narrators of Poe’s “The Fall of the House of Usher” and Welty’s “Why I Live at the County P.O”? Are Poe’s and Welty’s narrators also unreliable but honest? Are they unreliable for different reasons? Literature: Craft & Voice | Delbanco and Cheuse | Chapter 7 For Further Consideration 1. Explain how point of view can be used to add suspense and ambiguity in “Brownies,” “The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber,” and “The Yellow Wallpaper.” 2. Explain how “Brownies,” “How to Become a Writer,” and “The Yellow Wallpaper” are stories about writing. What do they tell us about the birth or development of a writer? What do they say about the importance of writing to the author? 3. Rewrite an excerpt from one of these stories in a different point of view. You might, for example, write “Brownies” from Daphne’s perspective, “Francis Macomber” from Margot’s, the husband’s in “Yellow Wallpaper,” and “How to Become a Writer” from he third person. Literature: Craft & Voice | Delbanco and Cheuse | Chapter 7