Pre-AP English-5-S Strategies

advertisement

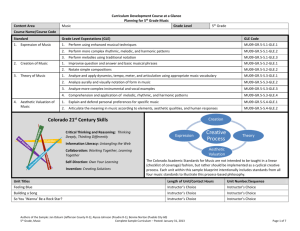

Pre-AP English: The 5-S Strategies for Passage Analysis Author: Connie Shelnut 1 Why Pre-AP and the 5-S Strategies? To introduce AP terminology and analysis strategies gradually in grades 6 through 12. To provide the building blocks for writing success to ALL college bound students. To provide teachers and students tools to efficiently target important components of poetry or prose for analysis. To provide teachers and students a structure to develop close reading skills in all grade levels and all subjects. 2 Apply three basic literary terms (Diction, Syntax and Imagery) used in passage analysis to a short poem to gain a deeper sense of how, through close reading, such terminology can focus and deepen the quality of any analysis. 3 Helpful Hints for Beginning Analysis: Have dictionaries handy for students to look up unfamiliar words. Choose a word definition appropriate for the context of the passage. Re-read the passage or poem and seek answers for what is unusual or significant in the diction, syntax or imagery? 4 Opportunity by Edward Sill This I beheld, or dreamed it in a dream:-There spread a cloud of dust along a plain; And underneath the cloud, or in it, raged A furious battle , and men yelled, and swords Shocked upon swords and shields. A prince’s banner Wavered, then staggered backward, hemmed by foes. A craven hung along the battle’s edge, And thought, “Had I a sword of keener steel – That blue blade that the king’s son bears – but this Blunt thing!” he snapt, and flung it from his hand, And lowering crept away and left the field. Then came the king’s son, wounded, sore bestead, And weaponless, and saw the broken sword, Hilt-buried in the dry and trodden sand, And ran and snatched it, and with battle-shout Lifted afresh he hewed his enemy down, And saved a great cause that heroic day. 5 Activity with the poem, Opportunity Circle words that you think are significant or important and ask yourself why this use of diction is important. Underline places in the passage that contain significant syntax and ask yourself why it is important. What does it do? Put an asterisk over words or phrases that evoke imagery. Ask yourself what creates this imagery. Discuss with group and share results 6 Review basic literary terms most often used in analysis Become familiar with the 5-S Strategies for Passage Analysis and reflect on the skills that effective close reading entails 7 Basic Terms for Passage Analysis Allusion – reference to a famous person or fictional character, 8 assuming the reader knows the connection Crux – the most crucial line(s) in a poem or prose passage that shows the main point Dialogue - conversation between two or more characters set off by quotation marks Diction – an author’s choice of words, i.e. denotation, connotation, slang, etc. Figures of Speech – states something that is not literally true in order to create an effect, i.e. comparisons such as similes, metaphors, and personification OR tropes such as allusions, apostrophes, oxymorons and hyperboles Imagery – descriptive words that appeal to the five senses Irony – surprising, interesting or amusing contrast between reality and expectation Basic Terms for Passage Analysis continued Meter – the rhythmic pattern of poetry: iambic, anapest, dactyl, 9 trochee and spondee; and number of measures: tetrameter, pentameter, hexameter, etc. Mood – feeling created by the passage or poem Motif – a thematic pattern repeated in the passage Organization – the means by which the passage is presented: chronological, thematic, etc. Plot – the sequence in which the author arranges the story events – developed by conflict, flashback, foreshadowing, suspense Point of View – from whose view is the passage related – note any shifts of speakers Punctuation – dashes, commas, italics, etc. Sentences (Syntax) – types, functions, patterns Sentence Variety – short, long, openings, order Basic Terms for Passage Analysis continued Setting – the place and time period of the story Sound Devices – alliteration, assonance, consonance, 10 onomatopoeia, rhyme, rhythm Style – a writer’s typical way of expressing himself, including his choice of diction, syntax and imagery Syntax Techniques – anaphora, antithesis, ellipsis, juxtaposition, parallelism, repetition, inversion, rhetorical question, punctuation, etc. Symbolism – a physical object that stands for an idea, i.e. our flag represents American ideals Theme – the unifying idea of the story that answers the question, “What is the work about?” Tone – author’s attitude toward the subject (shown by the diction used) – any shifts are very important Voice – the speaker or narrator telling the story, 1st, 2nd or 3rd person, omniscient, etc. Activity with the poem, Opportunity Reflect on the list of terms and check the ones that you use with your own students. Place check marks next to the terms used regularly and place a tentative grade level next to those terms. Working with the table group, compare annotations, discuss order and level for introduction of the top 10 terms One person serves as the recorder to share table results with the whole group 11 Activity with the poem, Opportunity Reflect upon on your own teaching to determine the aspects of diction, syntax and imagery that you should emphasize with their students. Write out your list and share it at your table One person serves as the recorder to share table results, in grade level order, with the whole group 12 Purpose of 5-S training: To provide students the building-blocks needed to develop reliable close-reading and analysis skills To give students using the 5-S close- reading skills an edge for better reading and analysis in any class 13 5-S Strategies for Passage Analysis 1. Discover the key sentences. Preview the passage by reading the first sentence, the last sentence, and by skimming the text in between to determine the scope of the work. By carrying out this step first, you gain an overview that allows for effective pacing. 2. Discover the speaker. Look for such things as the number of speakers and the narrator’s point of view – this is most often either first-person (omniscient, limited omniscient, or objective). Unless otherwise specified, analyze from the speaker’s vantage point. Note anything that gives a clue about the speaker’s attitude 14 5-S Strategies for Passage Analysis 3. Discover the situation. What is happening? State the situation in one clear sentence. Be sure to examine the title of the piece and its relevance to the situation. 4. Discover the major shifts in structure, syntax, or diction, such as wording that evokes certain connotations and sudden changes in tone, attitude of the author, sentence length, rhythm, punctuation, or patterns of imagery. Find areas of the passage where you can locate the most dramatic changes, and closely annotate them. 15 5-S Strategies for Passage Analysis 5. Discover obvious concentrations of unusual or otherwise significant syntax and its purpose. Look for changes in sentence length, sentence order, use of punctuation, and typographical elements such as italics, sentence inversion, or rhetorical questions, etc. that create emphasis. Mark the predominant syntax. Often it will guide the reader to the part of the passage that conveys the most meaning – the crux. 16 Activity with the poem, Opportunity Participants need to extend the list of elements that cause a sudden change – or shift – within a passage. Shifts are the clues to meaning that students must recognize to successfully “decode” writing. Participants should brainstorm ways that shifts occur – for instance, changes in sound is a helpful beginning Using the list of terms as a guide, work at each table to find shifts in the poem and the effect produced 17 Purpose: To demonstrate how the 5-S Strategies may be applied to poetry analysis Activity with the poem, Richard Cory Read the E. A, Robinson poem, Richard Cory, aloud. A second and even a third reading aloud is helpful to students unused to or afraid of poetry Write out your responses to the 5-S’s of the poem and share with your group 18 Richard Cory by E.A. Robinson Whenever Richard Cory went down town We people on the pavement looked at him: He was a gentleman from sole to crown, Clean favored, and imperially slim. And he was always quietly arrayed, And he was always human when he talked; But still he fluttered pulses when he said, “Good-morning,” and he glittered when he walked. And he was rich – yes, richer than a king, And admirably schooled in every grace: In fine, we thought that he was everything To make us wish that we were in his place. So on we worked, and waited for the light, And went without the meat, and cursed the bread; And Richard Cory, one calm summer night, Went home and put a bullet through his head. 19 There are 3 basic rules for Poetry or Prose Analysis: All of the details within the poem must be accounted for in the interpretation – none should contradict the interpretation. The best interpretation is that which requires the fewest assumptions – but that allows for reasonable and logical inferences to be made from word clues. If you run out of supporting evidence from the poem, stop interpreting – some things may be left unknown. We cannot know why Richard Cory killed himself, just that he was distraught enough to do so. 20 When creating an “Analysis” prompt for students to address, don’t forget – “Analysis” comes in two varieties: The “What – How” type that requires the student to identify a “What”, such as the author’s attitude or purpose, or the effect of the passage upon the reader, and “How” the author achieved the “What”, such as with the rhetorical strategies of diction, syntax, imagery, personification, irony, satire, humor, punctuation, allusion, etc.. The “Compare – Contrast” type that requires the student to read two passages and compare them for similarities and differences in such areas as noted above in the “What” and “How” discussion. 21 An Example Prompt of the “What – How” sort: Read the excerpt from “A Day in the Life of a Writer”. Then, analyze the author’s attitude toward the subject of the passage (what) and its effect upon the reader (what). Discuss the rhetorical strategies used to achieve both (how) and (how). 22 Students should begin their paragraph or essay with a claim that broadly answers the “what” and the “how”, then go on to prove it with evidence and explain what is revealed. Of course, students are expected to provide specific examples from the text of the poem or passage to support both the “what” and the “how” that they claim is true. 23 Activity– Prose Analysis The following passage contains wording that connotes speed, but the syntax does not enhance the effect of diction. Think of some syntactical tools you could use – i.e., punctuation, repetition, or clauses and phrases linked together in different patterns and orders. Then experiment with syntax to create a fast pace, so the reader feels the rush of the wind and the racing vehicle. Change any diction that you feel would add to the pacing. Share your ideas with your table group and choose one sample to read aloud to the whole group. 24 Around the bend sped the yellow racecar. Sparks darted from the wheels. The car tilted slightly at the bend. Roaring was everywhere. The driver felt the whoosh of wind flatten the skin on her face. She navigated yet another hairpin turn and kept on zooming around the track. The wheels appeared to hover above the ground. The crowd soon became dizzy with motion. 25 Excellent 26 Sentences -accurate forecast -examples Speaker -accurate forecast -pt of view effect Situation -accurate -connect to title Shifts -examples -thorough -devices Syntax -examples -discussion -connection Crux -main message Good Needs Work