What is the use of lectures

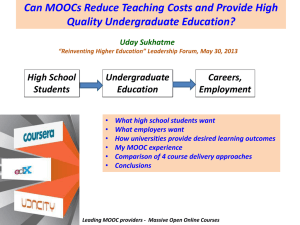

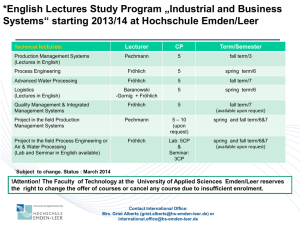

advertisement

Revisiting Donald Bligh in the 21st century Dave Laughton Sheffield Business School “Donald Bligh first published ‘What’s the Use of Lectures’ in 1972. Bligh outlined both the problems of using lectures in teaching and learning as well as some of the potential of this mode of instruction. But how has our practice responded to this pioneering work? In this session I will explore the notion of ‘boredom in the lecture theatre’ and introduce some pod casts with students reflecting on their lecture experiences. This will lead to a general discussion of how we can design and structure lectures for educational impact within the context of the overall pedagogical approach of modules.” 14th century image of a school, from Wikipedia “Scholastic schools had two methods of teaching. The first was the lectio: a teacher would read a text, expounding on certain words and ideas, but no questions were permitted; it was a simple reading of a text: instructors explained, and students listened in silence.” Wikipedia “The second was the disputatio, which goes right to the heart of scholasticism. There were two types of disputationes: the first was the "ordinary" type, whereby the questions (quaestiones) to be disputed were announced beforehand; the second was the quodlibetal, whereby the students proposed a question to the teacher without prior preparation. The teacher advanced a response, citing authoritative texts to prove his position. Students then rebutted the response, and the quodlibetal went back and forth. Someone took notes on what was said, allowing the teacher to summarise all arguments and present his final position the following day, riposting all rebuttals.” Wikipedia Universities now research and study a huge number of subjects – not just religion – are lectures universally useful as a teaching approach? Pedagogical competition – from experiential learning, activity-based learning, student centred learning, transformational learning etc “Boredom in the lecture theatre” – attention spans in the digital age Lectures as effective as other methods for teaching information but no more effective; forty studies reviewed suggested that unsupervised reading is better than lecturing Lectures ineffective in stimulating higher order thinking Lectures cannot be relied upon to inspire or change students’ attitudes favourably Students like really good lectures, but as a rule prefer groupwork "The findings suggest that 59% of students find at least half their lectures boring with 30% claiming to find most or all of their lectures boring" p253. Student coping strategies (rank order): daydream, doodle, switch off, colour in letters on the handout, talk to next person, text, write notes to friend etc. Rank order boredom ratings of teaching methods: Lab work Computer sessions Online lecture notes Copying overheads in lectures Powerpoint without handout Workshops Video presentations Group work outside of lectures Powerpoint with handout Do we need lectures at all – should we just get rid of them? If we have them could they be 30 rather than 60 minutes long? Can they be a small part of an integrated lecture/seminar approach Could they be less about ‘transmitting’ knowledge and more about: ◦ Exploring a problem ◦ Telling a story ◦ Mapping the intellectual landscape around a particular issue/topic ◦ Edutainment Could they be made truly interactive? Could they avoid the use of Powerpoint (the weapon of mass instruction)? Feedback to students and lecturer is needed Rehearsal (in the lecture) is needed Encourage deep processing Reduce the intensity with self-pacing Active learning (in the lecture) is better Maintain high levels of attention Foster motivation by activity Accept and use human nature - small group discussions are natural Teach thought and feeling via discussion How do you design lectures to maximise student learning? Bligh, D. (1998) "What's the Use of Lectures?", Intellect, Exeter, England. Mann, S. and Robinson, A. (2009) "Boredom in the Lecture Theatre: an Investigation into the Contributors, Moderators and Outcomes of Boredom Amongst University Students", British Educational Research Journal, vol. 35, No. 2, April 2009, pp. 243-258.