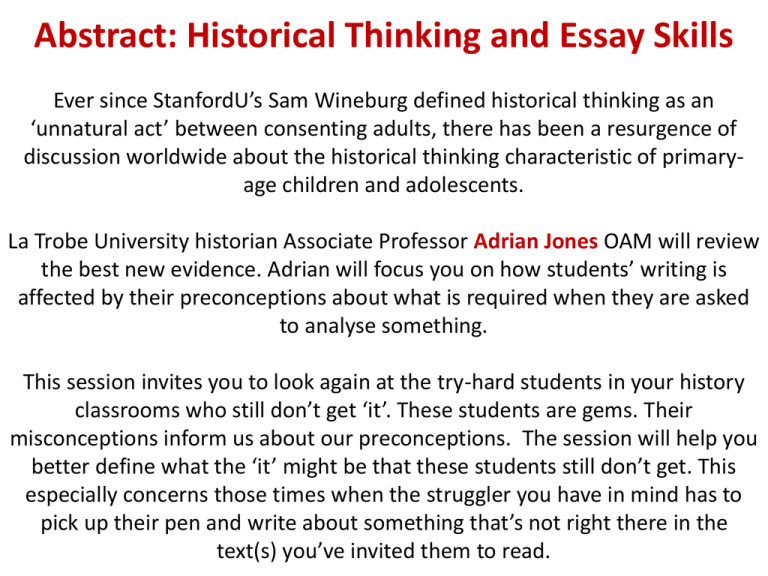

Abstract: Historical Thinking and Essay Skills

Ever since StanfordU’s Sam Wineburg defined historical thinking as an

‘unnatural act’ between consenting adults, there has been a resurgence of

discussion worldwide about the historical thinking characteristic of primaryage children and adolescents.

La Trobe University historian Associate Professor Adrian Jones OAM will review

the best new evidence. Adrian will focus you on how students’ writing is

affected by their preconceptions about what is required when they are asked

to analyse something.

This session invites you to look again at the try-hard students in your history

classrooms who still don’t get ‘it’. These students are gems. Their

misconceptions inform us about our preconceptions. The session will help you

better define what the ‘it’ might be that these students still don’t get. This

especially concerns those times when the struggler you have in mind has to

pick up their pen and write about something that’s not right there in the

text(s) you’ve invited them to read.

Cracking the Code (Analysis & Essays in History)

Decoding the Discipline (History)

The sustained feats of analysis required in the history essay can

seem to students arcane, unnatural and a teacher’s whim:

1.

Learning practices are too often implicit. Glib

comprehension may seem to have been just fine in school

before, so why do those damn teachers and academics

want analysis now?

2.

Attending more to learning outputs than inputs.

Teachers and academics worry more about grading essays

than they worry about how students learn to analyse

things in history.

3.

Agendas for learning give mixed messages. The essay as

key training venue for arriving at deeper learning is

distorted because it often doubles as an external and/or

summative assessment tool. Students have to learn how

to think just when they are learning how to write.

Which of these are really examined in essays?

Reference (1): “Decoding the Disciplines”

as practised by Indiana U historians:

Arlene Díaz, Joan Middendorf, David Pace & Leah Shopkow, “The History

Learning Project: A Department ‘Decodes’ its Students”, The Journal of

American History, 94(4) 2008, 1211-24; David Pace, “Decoding the

Reading of History: An Example of the Process” in Decoding the

Disciplines: Helping Students Learn Disciplinary Ways of Thinking in New

Directions for Teaching and Learning, 98 (summer 2004), ch. 2.

http://www.ntlf.com/issues/v16n2/v16n2.pdf

Reference (2): “Decoding the

Disciplines” as practised by Australian

based academic historians:

http://bit.ly/1maZNXd

a site under development I’ve been

working on with Prof. Jennifer Clark at

UNE, and with other Humanities

people in six other Australian

universities.

Form groups of four by pairing and turning

back. Swap stories for four minutes; one

minute each. Think about a try-hard

student in your class who still gets essay

researching and writing all “wrong”.

Define one error. Be specific. Text me.

Free text message to +61427541357,

and then on the message line enter

648603 first so the system knows to

which poll to send your response.

THINKING ABOUT YOUR STUDENTS, WHAT DO YOU THINK ARE THEIR

KEY BOTTLENECKS TO THEIR LEARNING OF HISTORY?

The quest: Release our students’ hidden History smarts!

In the same groups over the next four minutes, think

again about those try-hard students in your classes

who get essay researching and writing all “wrong”.

Decode together the nature or the source of the

student misconception prompting one such error.

Text me that. Be specific.

Another free text message to the same

number +61427541357, but on the

message line now enter 648633 first so

the system knows to which poll to send

your response.

PS: We have been in-servicing by practising

“decoding the disciplines”. The next step (we won’t

take here) is to ask what you can do as a teacher to

move the students through and past each particular

common misconception. Most often it requires being

much more explicit about everything we do.

Teachers and academics don’t do enough “read

alouds” for instance. “Decoding” was designed for

academics. They suffer more from hubris, but they

are dumber about student learning than teachers.

BOTTLENECKS IDENTIFIED BY HISTORIANS AT INDIANA U

1. MISUNDERSTANDING THE ROLE OF FACTS

INTERPRETATION ≠ ACCUMULATION

2. INTERPRETING PRIMARY SOURCES

SOURCES COME FROM CONTEXTS AND FROM ACCIDENTS OF DELIVERY

3. MAINTAINING EMOTIONAL DISTANCE

BEING RESPECTFUL OF A PAST, YET STILL SCEPTICAL & CRITICAL

4. & 5. UNDERSTANDING THE LIMITS OF HISTORICAL ACTORS & IDENTIFYING WITH

PEOPLE IN ANOTHER TIME AND PLACE

MY KNOWLEDGE ≠ THEIR KNOWLEDGE – STUDENTS’ READINESS TO

RELATIVISE

THOUGHTS AND EXPERIENCES OF THE HISTORICAL SUBJECTS THEY

STUDY

AND INDEED THEMSELVES

6. CONSTRUCTING AND EVALUATING ARGUMENTS

REALISING LINES OF ARGUMENT AREN’T FOUND, THEY ARE CONSTRUCTED

BY AN HISTORIAN OUT OF EVIDENCE, YET ALSO NOT SURRENDERING TO THE

RELATIVISMS INTEGRAL TO THAT REALISATION

7. LINKING SPECIFIC DETAILS TO A BROADER CONTEXT

DIFFICULTIES STUDENTS HAVE WITH LINKING SPECIFIC STUFF THEY KNOW

ABOUT A PAST TO WIDER “ISSUES” OR LINES OF ARGUMENT ABOUT PASTS

Theodore de Bry

(1528-98) satirical

woodcut (1569) of a

schoolroom from his

emblem book:

“Emblemata

nobilitate et vulgo

scitu digna

(Emblems suitable

for the nobility and

the common people

to know)”

You succeed

in nothing

and you

learn nothing

against your

inclination

Frankfurt-am-Main 1569

or 1590s.

The Newberry Library,

Chicago, or Wake Forest

University, Winston-Salem,

USA, item PC1935.7:

http://www.newberry.org/ &

http://www.wfu.edu/academi

cs/art/pc/images/pc-bryinvita.jpg

Dai Hounsell on student conceptions about essays

“Learning and Essay Writing” in The Experience of Learning, eds Ferenc Marton et al., Edinburgh, Scottish Academic Press, ch. 7

;“Toward and Anatomy of Academic Discourse: Meaning and Context in the Undergraduate Essay” in The Written World, ed. Roger

Säljö, Berlin, Springer, 1988, ch. 10; “Reappraising and Recasting the History Essay” in The Practice of University History Teaching, eds

Alan Booth et al., Manchester, Manchester University Press, 200, ch. 14.

• Essays just seek an arrangement of stuff I know

– Facts speak for themselves. Knowledge is a bucket. People

with the most facts win in life. You just re-arrange the stuff.

• Essays just offer an occasion to give my point of view

– Tweak the facts so they speak my way. Essays just want to

know what I think. When teachers ask me for evidence that

just means they want me to describe better what I think.

• Essays task me to develop a line of argument

– I have to order facts and make them speak something (else).

I know different people can write differently about the same

things and still be “right”. There just has to be evidence and

an evident and balanced pattern to everything I mention.

How might a teacher develop

students' confidence and capacities to

write evidence-based essays? Offer

something short and specific.

Confer for another four minutes in the same

group, and then send me another free text

message to the same number +61427541357,

but on the message line now enter 650433 first

so the system knows to which poll to send your

response.

Chauncey Monte-Sano (U Michigan) on what makes a

difference in learning evidence-based historical writing

“Qualities of Historical Writing Instruction: A Comparative Case Study of Two Teachers’ Practices”, American

Educational Research Journal, 45(4) 2008, pp. 1045-79.

• “approaching history as evidence-based interpretation”

• “reading historical texts and considering them as

interpretations”

• “supporting reading comprehension and historical

thinking”

• “asking students to develop interpretations and

support them with evidence”

• “using direct instruction, guided practice, independent

practice, and feedback”

• “The act of writing alone is not sufficient for growth in

evidence-based historical writing.”

Reference (3): New US work on

adolescents’ historical thinking. There is

fine Dutch, Spanish and British work too!:

Sam Wineburg’s students: Susan de la Paz et al. “Adolescents’ Disciplinary Use of Evidence,

Argumentative Strategies and Organizational Structure in Writing about Historical

Controversies”, Written Communication, 29(4) 2012: 412-54; Monte-Sano & de la Paz, “Using

Writing Tasks to Elicit Adolescents’ Historical Reasoning”, Journal of Literacy Research, 44(3)

2012: 273-99.

Stuart Greene, “The Problems of Learning to Think like an Historian”, Educational Psychologist,

29(2) 1994: 89-96 and “Students as Authors in the Writing of History” in Teaching and Learning

in History, eds Gaea Leinhardt et al., New York, NY: Routledge, 2009.

Kathleen McCarthy Young and Gaea Leinhardt, “Writing from Primary Documents: A Way of

Knowing in History”, Written Communication, 15(1) 1998: 25-68.

Lorraine Huggins, “Reading to Argue: Helping Students Transform Source Texts” in Hearing

Ourselves Think, eds Ann Penrose & Barbara Sitko, New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1993,

ch. 5.

Other researched perspectives

on historical thinking

Peter Lee & Rosalyn Ashby (Institute of Education, University of London)

‘Progression in Historical Understanding among Students ages 7 to 14’ in Knowing, Teaching and Learning

History: National and International Perspectives, eds Peter Stearns, Peter Seixas & Sam Wineburg, New York:

New York University Press & The American Historical Association, 2000, ch. 11.

1. Nonsense. ‘The Blind Monkey.’ We can’t know about history. We

weren’t there – unless they’re dinosaurs. Does icky-picky history

stuff matter? Wonder is better anyway. (Junior Primary?)

2. Evidence. ‘Left-Overs’. Literalism. Only with what’s here and now,

can we possibly know about history. (Senior Primary?)

3. Bias. ‘Bulldust!’ Someone else with an axe to grind selected what

we know about history. It’s all baloney anyway. (Mid-Secondary?)

4. Orientation. Me! Me! Me!. That might be interesting, but it really

all depends on the individual. Arguments and evidence are just

points of view: mine and theirs. My views are better. (Senior

Secondary?)

5. Relativity. ‘Me Tarzan, You Jane’. The stuff I know oddly depends

on me. Questions we ask prompt evidence we find which shape

what we know about history. I therefore need to be open to new

Denis Shemilt (University of Leeds)

‘Adolescent Ideas about Evidence and Methodology in History’ in The History Curriculum for Teachers, ed.

Christopher Portal, London, Falmer, 1987, ch. 3, a study of 167 15-year-olds in 24 English schools who had to

keep on explaining why and how we know stuff about History.

1

2

3

4

The

Past

is

a

given.

Sources

mean

one

thing.

What

the

teacher

told

us is

true.

Historians

are

expert

memory

people

who

know

everything

about

the

past.

What

could

I possibly

know?

Ionly

go

with

the

flow.

The

Past

is

“out

there”

to

be

found.

Sources

still

only

mean

one

thing,

but

different

people

privilege

different

information.

That’s

why

there’s

bias.

Historians

sort

the

wheat

from

the

chaff.

We

just

look

for

the

bias

we

prefer.

The

has

to

be

nutted

out

by

The

information

inandin

sources

isactually

indeed

“out

there”,

only

when

itcan’t

been

critiqued

evidence.

Historians

draw

inferences

from

evidence.

Historians

will

differ

what

and

how.

This

uncertainty

annoys.

Why

they

work

itfor

out?

The Past

Past

is

aanswers.

Historian’s

Reconstruction

using

ahas

Method.

We

can’t

know

about

the

past

for

sure,

but

webut

can

infer

itssomeone.

characteristics

using

different

methods

to

interrogate

sources.

It’s

fun

to

compare

sources,

methods

results,

even

if there’s

no

single

right

answer,

only

lots

ofjust

wrong

or

incomplete

Jörn Rüsen (Zentrum für interdisziplinäre Forschung, Bielefeld and

Kulturwissenschaftliches Institut, Essen)

Rüsen, ‘Historical Consciousness’ (1989, 1997) in Peter Seixas, ed., Theorizing Historical Consciousness, Toronto,

The University of Toronto Press, 2006, pp. 63-85 @ 70-79.

1 Traditional-Biblical. Ways lives are/were lived

are/were pre-ordained and obligatory.

2 Traditional-Exemplary. Timeless rules and values

shape past and present lives.

3 Critical. Pasts are a problem for me: my times now

relativise theirs in their past. The past is either

perpetually in deficit or looking rather nostalgic.

4 Genetic. O.M.G. Everything’s in flux: my own familiar

now actually depends on my particular time and

context, and so were they back in their then, and so

is time itself. Is there any meaning in anything?