Gilgamesh

advertisement

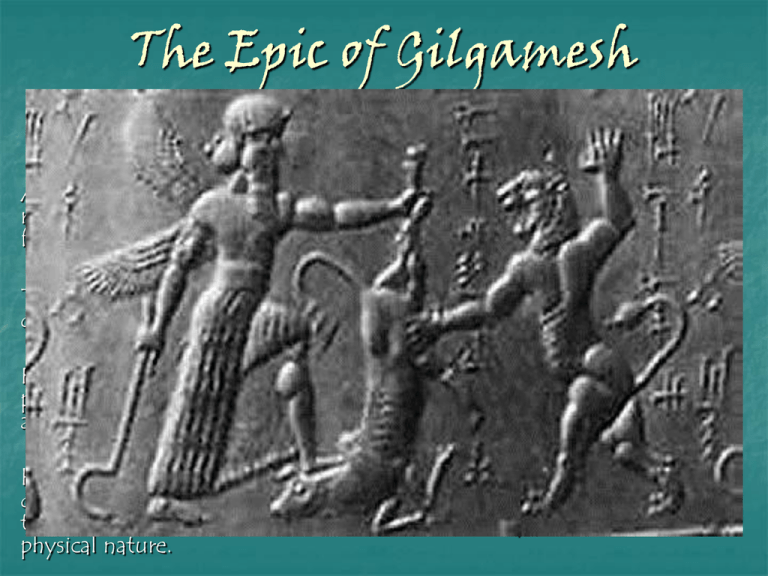

The Epic of Gilgamesh Timor mortis conturbat me “The fear of death consumes me” All of the episodes in the poem share this common theme--how the realization of death is a motivation for the hero’s actions and a defining feature of our search for identity. The poem expresses a very pessimistic view of human life and the world-due in part to the insecurity of life in Mesopotamia. From the start of the poem, we see Gilgamesh with an over-riding preoccupation with fame, reputation, and the revolt of mortal man against the laws of separation and death. His 2/3 divinity yoked with his mortal third becomes an internal dilemma which drives much of the movement; it is a conflict that lies at the heart of all mankind: to reconcile our divine aspirations with our physical nature. Gilgamesh’s completer, Enkidu, shares many of the hero’s traits, and he also stands as his opposite. Enkidu’s part-man, part-beast nature is the reverse of Gilgamesh’s human-divine mix. The relationship of Gilgamesh and Enkidu is an essential element in Gilgamesh’s growth. Enkidu’s death is the primary motivational force that propels Gilgamesh on his journey for eternal life. It is important to note that Gilgamesh sets out on his quest for SELFISH REASONS. He is not trying to revive Enkidu from the dead. Rather, he is now intimately aware of the consequences of death, and he wants to avoid a similar fate. Gilgamesh’s journey is away from the center. He leaves civilization and enters the wilderness. Uruk is the seat of civilization and law. Entering the wilderness represents the movement away from what makes us human. In such, Gilgamesh regresses into a primal being, wearing lion skins and looking worn and weary. Paradoxically, in trying to gain everlasting life, he rejects the qualities that define what he should be--the King of Uruk Gilgamesh’s journey is also a journey into the past. He figuratively travels back in time to encounter a man who lived before the Flood. Most significantly, Gilgamesh’s journey is a journey into self. As a common archetypal pattern, Gilgamesh must lose all the trapping and symbols of his position in order to strip down to his essential self. That is his most harrowing test: to face who he really is. All of these patterns illustrate the growth of identity. Prologue Extols Gilgamesh’s traits & accomplishments: Knowledge Wisdom Quest Ability to Write Divine/Human Composition Grandeur of Uruk—particularly its WALLS (p. 13) The city represents safety, civilization, and law. The qualities of the King are reflected in the qualities of the city, and vice versa. The Coming of Enkidu Enkidu is Gilgamesh’s Rival/ Companion Alter Ego/Doppelganger Reflector/Foil Completer. The two heroes together form one unified whole. Enkidu’s growth demonstrates the archetype of innocence leading to experience (often through sexual awareness). Wisdom replaces innocence. Civilization replaces the wild. Enkidu proclaims, “I have come to change the old order” (pp. 15 & 17). His interactions with Gilgamesh dissipate Gilgamesh’s selfish, hedonistic drives (p. 17). Symbols to note: Face Dreams Clothing Gates The Forest Journey This passage emphasizes how civilization overcomes the wilderness. How Law (the qualities of Mankind) replaces Chaos (the features of the Beast). Also the domain of Humbaba is associated with evil (p. 18), giving Gilgamesh’s adventure a moral dimension. It is also blessed by the Sungod, Shamash (p. 18). The section also examines Man’s “restless desire” (p.19) and his “restless heart” (p. 20). The hero must perform deeds to prove himself, and the deeds must be of epic size. This TEST is the hallmark of the hero. Through these acts, the hero acquires personal Fame, which is very important to the earliest cultures, and he elevates the entire culture and human race. So both the individual and society profit from the contest. Enkidu at first fears Humbaba because Enkidu has experience in the wilderness (pp. 18, 21, & 23). But his companionship with Gilgamesh overcomes the dread, and they are able to vanquish the giant TOGETHER. The Forest Journey Gilgamesh’s heart is “moved with compassion” when Humbaba pleads to him (p. 24). Now Enkidu questions Gilgamesh’s judgment, and the two slay the Guardian of the Cedar Forest. Although the heroes are aided by the Sun-god Shamash who supplies them with the winds, other gods are angered over the death of Humbaba. Enlil, the god of earth, wind and spirit, curses the pair (p. 25). The gods do not like this New Cosmic Order that has been establish in which Man betters the Natural World. Symbols to Note: Journey/Quest The Forest Faces Dreams Sleep Gates Test Ishtar & Gilgamesh The goddess of fertility is attracted to Gilgamesh though his deeds. His Fame has consequences. Ishtar’s advances are an honor--Gilgamesh will be taken into the cycle of renewal and be elevated even further, such as Dimuzi had been. Yet, Gilgamesh refuses the offer which slights the goddess--the hero is always pushing the envelop, redefining Man’s relationship with his surroundings, with the divine, and within the Cosmic Order. Ishtar threatens the release of chaos (p.26), so the gods relent and give her the Bull of Heaven to punish Gilgamesh. Bulls are sacred animals in many Middle Eastern and Mediterranean cultures. The killing of the Bull of Heaven and the subsequent insult to Ishtar is an affront to the divine--Man does have limits, as the epic proves over and over again. Enkidu is cursed, and his body (his defining feature and most mortal aspect) becomes his destruction. The Death of Enkidu Enkidu’s Dream of the Underworld is a frightening glimpse into the Sumerian Afterlife. This dark world inhabited by vampire-faced creatures where the dead are slaves who eat dust and clay reveals much about Sumerian existence since the stories of our Afterlife are based on our Earthly life. Gilgamesh’s Lament (pp. 30-31) is formulaic and ritualistic. At Enkidu’s death (p. 31) Gilgamesh’s anguish is unbounded (as is fitting the hero), and he begins his regression. Symbols to Note: Dreams Sleep Gates Clothing The Worm The Search for Everlasting Life Gilgamesh sets out for purely selfish reasons (p. 31). His journey is a regression--a reverse of the evolution of man. His encounter with the pride of lions shows a primordial response to the natural world (31-32). The Scorpion-Men, fitting guardians for the 12 leagues of darkness under the Mountain of Mashu (a descent image), advise against the journey. Gilgamesh responds, “still I must go” (p. 32)--life lessons have to be experiential. Shamash begins a series of encounters in which everyone tells Gilgamesh essentially the same thing: “You will never find the life for which you are searching” (p. 33). Remember, Shamash is the Sun-God, and he is “distressed” by Gilgamesh’s appearance, showing that there is something amiss with the hero’s adventure. The Search for Everlasting Life Siduri, the wine goddess who lives in an Eden-like Garden of the Gods, tells Gilgamesh to enjoy life--an early proponent of carpe diem (seize the day). The passage over the Waters of Death is reverse birth images. The island is often a symbol of the womb, and as such, Gilgamesh is returning to a prebirth state. Urshanabi, the ferryman, is a common mythological figure to take people to a new reality--usually after death. Utnapishtim, the Sumerian Noah, tells Gilgamesh the futility of his adventure after Gilgamesh asks the epic question: “how shall I find the life for which I am searching?” (p. 36) Symbols to Note: Darkness & Blindness vs Light & Sight Ferryman Water Garden The Island The Story of the Flood The story contains obvious parallels with the biblical Flood story. Yet, the actions and influence of the gods are quite different, indicating the different attitudes the Sumerians and Hebrews had toward the divine and our human responsibilities for our fate. The Ark is an archetype of survival. In both the Sumerian and biblical accounts, the destruction of the world is achieved through a reversal of the creation process, and chaos is loosed. The greatest difference is in the end of the story. In the Bible, God and Noah (who represents all Mankind) are reconciled and form a covenant. In Gilgamesh, Mankind is still punished for his actions--these Sumerian gods are not forgiving deities. The Return The Test to stay awake. Human consciousness (identity) is an on-going theme within the poem. We often see Gilgamesh falling asleep (e.g. prior to the battle with Humbaba, and the test with the loaves of bread). This pattern illustrates the growth of mankind into a conscious ego. Yet, the human consciousness is still limited. Once Gilgamesh fails the Test, he is sent to clean and renew himself (p. 40). He is re-born into a fully realized human being and is given clothing as a sign of his humanity. Gilgamesh has learned the limits imposed by our mortality. The plant that restores youth--The Old Men Are Young Again--is not the same as immortality; that has already been lost to us. This plant is a sort of consolation prize. Its importance lies in Gilgamesh’s altruism (pp. 40-41). He has gained wisdom instead of his original goal of immortality. Of course, the snake--a suitable archetype of evil--steals even this prize. On his return to Uruk, Gilgamesh is proud of his city, indicting the degree of his growth. The closing lines (p. 41) hearken back to the “Prologue.”