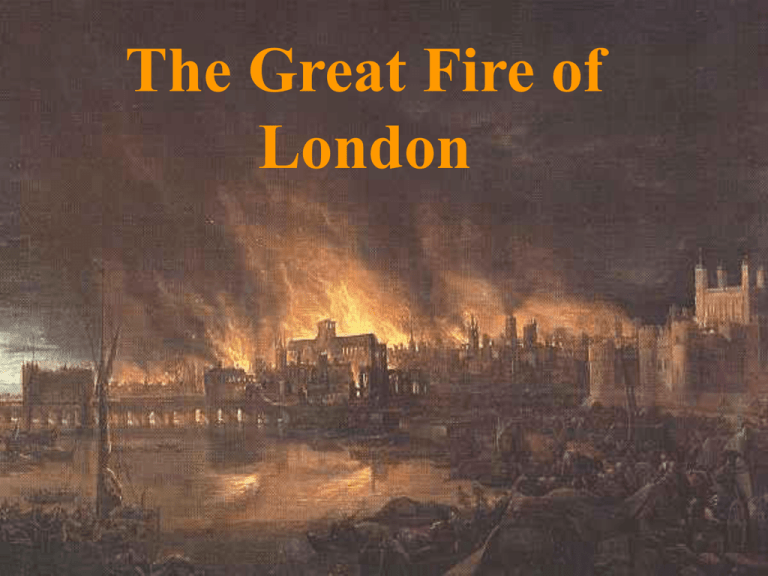

The Great Fire of London

advertisement

The Great Fire of London The fire started on a Sunday morning, in 2 September 1666 in the king's own bakery in Pudding Lane in the City. It took hold in Thomas Farryner's bakery kitchen that night,and it spread swiftly. A journeyman living above the bakery raised the alarm. The household jumped to safety from the roof – except for one maid who became the fire's first victim. the fire burned fiercely, spreading to buildings in Thames Street in the south, St Botolph's Lane in the east and Fish Street Hill. SUNDAY By Sunday morning, 300 buildings were in ashes, the fire had raged down to the river and the lord mayor was alternately ordering and begging people to pull down houses in its path. Many property owners refused, and even where buildings were pulled down, the heat of the fire was now so intense that it could 'jump' over firebreaks and ignite timbers on the far side. There was no central firebridge, this way local people tried to stop the fire using axes and iron fire hooks. This was quite inefffective so the fire, assisted by the strong winds burnt out of control. Buildings were full of burnable materials (oil, pitch (szurok)) which fuelled (táplál) the fire. Lord Mayor of London, Sir Thomas Bloodworth hesitated a lot which resulted in mayhem. MONDAY The fire raged for four nights and days. On Monday the fire spread to north (City), south (Thames street), east (St. Botolph’s Lane and Fish street). King Charles, fearful of public disorder, gave control of the metropolis to his brother, the duke of York, who set guards to control looting. Londoners poured out of their homes in a mass exodus, carrying what possessions they could away from the advancing fire. The price of a cart (talicska) rose from Ł3 to Ł30 and all boats were packed. Lots of them tried to escape with boats, but the river boats soon got packed. Those who left by road went to the high ground of Moorfields, Islington and Parliament Hill, where they camped and watched the City burn. A diarist, Samuel Pepys wrote that some families saved their musical instruments. TUESDAY On Tuesday, the fire burned westward and northward and, after midnight, consumed two great buildings, the Guildhall and Old St Paul's cathedral. The stones of Paul's flew like granados’ ' the melting lead running down the streets in a stream and the very pavements glowing with fiery redness.‘-wrote another diarist. The fire was checked in the east by gunpowder explosions, which created large firebreaks and saved the Tower of London. In the east: checked by gunpowder explosions, which created large firebreaks and saved the Tower of London. In the west: fire leapt the river Fleet, threatened to spread to Whitehall and the royal palaces. WEDNESDAY On Wednesday morning, the wind dropped , the fire lost intensity and broke up. It became possible to douse the flames, but people battled for another 36 hours before the last of the fires were finally extinguished on Thursday night. The fire destroyed more than 13,000 houses, 87 parish churches, 6 chapels, 44 Company Halls, the Royal Exchange, the Custom House, St Paul's Cathedral, the Guildhall, the Bridewell and other City prisons, the Session House, four bridges across the Thames and Fleet rivers, and three city gates. Amazingly, only five deaths were documented, but up to 200,000 people were left destitute. the total damage was estimated at over £10 million. At least 65,000 and perhaps almost 80,000 Londoners were made homeless. The fire is said to have also helped to get rid of the Great Plague which had hit London in 1665, and killed about 70,000 of the 90,000 population. The extent of the Great Fire of London 1666 Why could the fire spread so fast? Timber was the most common building material, and straw was laid on floors and stored in stables and outhouses. Pudding Lane was a narrow street of timbered buildings and wattleand-daub shelters, many of them housing cook shops. It backed on to Fish Street Hill, which led to London Bridge, itself lined with buildings made of plaster and wood. Many of the buildings housed storerooms full of combustible materials such as oil, pitch, hemp and tar. These fuelled the fire, and the heat was so intense that no one could get close enough to fight the flames. There was no central fire brigade. It had traditionally been up to local people themselves to deal with blazes, dousing the flames with leather buckets of water and beating them out with staves. Where fires threatened to spread, people would use axes, ropes and iron fire hooks to drag down wood-frame buildings and create firebreaks. Firehooks 17th century fire engine Contemporary accounts of the fire Acount of the Great Fire in the London Gazette St. Paul's Cathedral in flames. Oil painting ca. 1670. THE HERITAGE OF THE GREAT FIRE After the Great Fire of London in 1666, a massive rebuilding programme was needed. At first, it was seen as an opportunity to improve the layout of the City. As the images below indicate a number of people like Christopher Wren and John Evelyn submitted plans for a much more modern city, in 17th century terms, with wide streets and grand squares. A positive effect of the fire was that the 1665 plague stopped spreading, saving many thousands of lives. The flames destroyed unsanitary housing, killing rats and purging the capital of infection. The aftermath of the fire resulted in the building of 9000 new homes, which cused a labour shortage. Immigrant workers from other parts of Britain and from abroad came to the city and stayed there London’s population rose, by 1700 it was the largest city in Northern Europe. One further consequence of the fire was that by the end of the 17th century: London had three firebridges: The Fire Office (1680), The friendly Society (1683), the Hand-in-Hand Office (1696). Why were there so few deaths from the fire? The most important factor was that the fire took hold slowly and lasted only 4 days leaving plenty of time for people to save not only themselves but many of their belongings, too. Records of only five dead (nevertheless the number of the real dead may have been higher): Thomas Farryner's maidservant; Paul Lowell, a Shoe Lane watchmaker; an old man who went to rescue a blanket from St Paul's and was overcome by smoke; and two others who fell into cellars while rescuing their belongings. The main memorial to the fire is the famous Monument, designed by Sir Christopher Wren. It is 202ft tall, being the exact distance from the baker's house where the fire began in Pudding Lane. Visitors can climb the 311 steps to the top and enjoy spectacular views of London.