Analyzing Poetry - Mounds View School Websites

advertisement

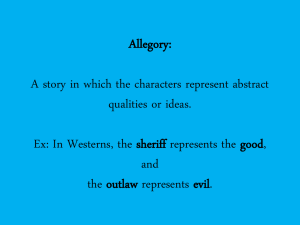

Analyzing Poetry “Poetry is nearer to vital truth than history” (Plato) And Dr. Seuss uses it, too! Prose The ordinary form of spoken or written language, without metrical structure, as distinguished from poetry or verse. Prose is the form of written language that is not organized according to formal patterns of verse. It may have some sort of rhythm and some devices of repetition and balance, but these are not governed by regularly sustained formal arrangement. The significant unit is the sentence, not the line. Hence it is represented without line breaks in writing. Novels, short stories, articles, works of nonfiction Poetry The art of rhythmical composition, written or spoken, for exciting pleasure by beautiful, imaginative, or elevated thoughts. Literary work in metrical form; verse. Poetry is language spoken or written according to some pattern of recurrence that emphasizes relationships between words on the basis of sound as well as meaning. This pattern is almost always a rhythm or meter (regular pattern of sound units). This pattern may be supplemented by ornamentation such as rhyme or alliteration or both. Poetry project due April 21 This partner-optional project will challenge you to use both your left and right sides of the brain. The left side, which is analytical, tends to see sequences, causes and effects, and differences. The right side, however, looks for patterns, emotions, images, analogies, and pictures. For this assignment, you will select a poem that is 12-30 lines long from poetryoutloud.org. On a sheet of tag board, you will arrange the poem and poet in the center and arrange the right- and leftbrain parts around it. The project will be worth 50 points. Please refer to the below rubric as you construct your project. The assignment is due Thursday, April 21, in the library (do not bring it to 259 on that day). Left-Brain Components Left-brain components include the following: an analysis of the poem (see sample on page 7 and TPCASTT explanation in packet), five key facts about the poet that are phrases IN YOUR OWN WORDS (give credit for this information) and three defined words (more credit). Submit all three parts to turnitin.com. Right-Brain Components Right-brain components consist of images from the poem and connections to your life (films, songs, or literature the poem reminds you of; colors; reactions; your original efforts inspired by the poem you’ve chosen. These should not just be images printed off the Internet. Be creative! Vary textures, colors, shapes, sizes. Poetry Project Rubric (Remember that the analysis must be submitted to turnitin.com, and the key facts need documentation! See rubric for expectations Use a flat piece of tag board (2 x 3 feet) Use a variety of textures and colors (unless black and white for artistic effect) Do not roll up the project to bring to school (please keep flat) Begin in the middle and work your way to the edges Document your sources—OR NO CREDIT. Rhythm in Poetry While not all poetry has rhyme, rhythm, or both, some does. The basic “beat” of poetry is called a FOOT. A foot could have one, two, or three syllables. Only one syllable is stressed for each foot. A stressed syllable = / An unstressed syllable = U Rhythm devices with three syllables Anapestic: three-syllable foot made of two unstressed syllables followed by a stressed syllable. An example of this would be comprehend (com-pre-HEND). Hmmm…how would Dr. Seuss handle the anapestic foot? If I Ran the Zoo by Dr. Seuss U U / U U / "So I'd open each cage. U U / U U / I'd unlock every pen. U U / U U / Let the animals go U U / U U / And start over again." Rhythm devices with three syllables Dactylic: three-syllable foot made of a stressed syllable followed by two unstressed syllables. An example of this would be merrily (MER-ri-ly). This is like the waltz beat: ONE two three, ONE two three (think pterodactyl doing the waltz) The Lorax by Dr. Seuss / U U / U U / U U / "I am the Lorax. I speak for the trees." Rhythm devices with two syllables Iambic: two-syllable foot made of an unstressed syllable followed by a stressed syllable. An example of this would be regard (re-GARD). Shakespeare used this, and so did Robert Frost. What about Dr. Seuss? U / U / U / U / “I do not like green eggs and ham. U / U / U / U / I do not like them, Sam I Am." Rhythmic devices with two syllables Trochaic: two-syllable foot made of a stressed syllable followed by an unstressed one. Think Poe's The Raven! An example would be raven (RAV-en). So Poe liked this. Did Dr. Seuss? What do YOU think? / U / U / U / U "One fish, two fish, red fish, blue fish.." Name the rhythmic device “And to think that I saw it on Mulberry Street.” Anapestic U U / U U / U U / U U / “And to think that I saw it on Mulberry Street.” Name that rhythmic device “I saw a pair of pale green pants With nobody inside them.” Iambic U / U / U / U / I saw a pair of pale green pants Name the TWO rhythmic devices “Now Sam McGee was from Tennessee, Where the cotton blooms and blows” Iambic and anapestic U / U / U U / U / Now Sam McGee was from Tennessee Name the rhythmic device “Tyger! Tyger! Burning bright In the forest of the night!” Trochaic / U / U / U / Tyger! Tyger! Burning bright! Name the rhythmic device Had I but all of them, thee and thy treasures, What a wild crowd of invisible pleasures! Anapestic / U U / U U / U U / U Had I but all of them, thee and thy treasures What’s a foot in poetry? The number of stressed beats in a line of poetry is a foot. Most poems have more than one foot per line: Dimeter (two beats) Trimeter (three beats) Tetrameter (four beats) Green Eggs and Ham by Seuss Pentameter (five beats)—SHAKESPEARE! Hexameter (six beats) Septameter (seven beats) Octameter (eight beats)—”The Raven” by Poe How many feet in these lines? Robert Service’s “The Cremation of Sam McGee”: Now Sam McGee was from Tennessee, where the cotton blooms and blows. Emily Dickinson’s “Because I Could Not Stop for Death”: Because I could not stop for Death, he kindly stopped for me. Robert Browning’s “The Laboratory”: Had I but all of them, thee and thy treasures. Dr. Seuss’ The Sneetches: Now the star-bellied Sneetches had bellies with stars, But the plain-bellied Sneetches had none upon thars. William Blake’s “The Tyger”: Tyger! Tyger! burning bright In the forests of the night SOUND DEVICES--what helps with rhyme? sound pictures? Alliteration: Repetition of initial sounds of words in a row. Example: Peter Piper picked a peck of pickled peppers. (Of course, alliteration is not always so concentrated) Assonance: Repetition of internal vowel sounds of words close together in poetry. Example: I made my way to the lake. Consonance: Repetition of internal or ending consonant sounds of words close together in poetry. Example: I dropped the locket in the thick mud. Onomatopoeia: Words that sound like their meaning. Example: splash, boom, whizz Rhyme True rhyme: words that rhyme with all ending sounds: Example: trouble and bubble. Sight rhyme: words that look alike but do not rhyme. Example: though and bough; good and food End rhyme: words that rhyme and occur at the ends of different lines of poetry Internal rhyme: two words that rhyme within one line of poetry ex. “We were the first that ever burst” Rhyme Scheme: the pattern of rhyme in a poem. To get the rhyme scheme, each line in the poem is assigned a letter. The first line gets an "A". If the next line rhymes with the first, give it an "A" also. If not, give it a "B". Continue throughout the poem, following the same rules: if the end word rhymes with anything before, match that letter. If not, give it the next unused letter of the alphabet. “Alone” by Edgar Allen Poe From childhood’s hour I have not been As others were; I have not seen As others saw; I could not bring My passions from a common spring. From the same source I have not taken My sorrow; I could not awaken My heart to joy at the same tone; And all I loved, I loved alone. a a b b c c d d What is the scansion (type of rhythm and number of feet)? Iambic tetrameter Beyond simile, metaphor, hyperbole, and personification Apostrophe Words that are spoken to a person who is absent or imaginary, or to an object or abstract idea. The poem "God's World" by Edna St. Vincent Millay begins with an apostrophe: “O World, I cannot hold thee close enough!/Thy winds, thy wide grey skies!/Thy mists that roll and rise!” Conceit A fanciful poetic image that likens one thing to something else that is seemingly very different. An example of a conceit can be found in Shakespeare's sonnet “Shall I compare thee to a summer's day?” and in Emily Dickinson's poem “There is no frigate like a book.” Litotes A figure of speech in which a positive is stated by negating its opposite. Some examples of litotes: no small victory, not a bad idea, not unhappy. Litotes is the opposite of hyperbole. Metonymy A figure of speech in which one word is substituted for another with which it is closely associated. For example, in the expression The pen is mightier than the sword, the word pen is used for “the written word,” and sword is used for “military power.” Synecdoche A figure of speech in which a part is used to designate the whole or the whole is used to designate a part. For example, the phrase “all hands on deck” means “all men on deck,” not just their hands. The reverse situation, in which the whole is used for a part, occurs in the sentence “The U.S. beat Russia in the final game,” where the U.S. and Russia stand for “the U.S. team” and “the Russian team,” respectively. Which type of figurative language? "for life's not a paragraph and death I think is no parenthesis" (e.e. cummings). “I should have been a pair of ragged claws Scuttling across the floors of silent seas” (T.S. Eliot) “But the hand! Half in appeal, but half as if to keep The life from spilling” (Robert Frost) “Twinkle, twinkle, little star, how I wonder what you are” (Mother Goose) “This flea is you and I, and this Our marriage bed, and marriage temple is” (John Donne). TPCASTT: A way to analyze poetry Title Paraphrase Connotation Attitude Shifts Title Theme Title Ponder the title before reading the poem. Make up questions about the title. There are two kinds of titles: interactive titles and naming titles. Interactive titles are have some sort of interplay with poem itself and can affect its meaning. Naming titles may give less crucial information. If a poem lacks a title, you can do this step with the first line of the poem or skip it. Paraphrase Translate the poem into your own words. And I mean translate! Word for word! Find synonyms for every possible word. Summarizing is NOT paraphrasing (see page 7 of the packet for a sample). Connotation Contemplate the poem for meaning beyond the literal. Identify and figure out the figurative language. Look for symbols and conceits (extended metaphors). Here also is where you will examine the form (rhythmic devices, for example). Attitude After identifying a subject/topic of the poem, figure out how the speaker (and/or the poet) feels about it. Look at word choice. Is the diction formal or informal? Look at tone. Is the poem ironic? Don’t assume the speaker and the poet are the same. Who is the narrator of the poem? Male or female? Young or old? Shifts Note transitions in the poem. Shifts in subject, attitude, or mood. Look for words like but or then. Look at the punctuation, like questions and answers Look for a change in verb tense (said to says) or person ( I to you, or I to he or she?) Look for a change in time Title (second time) Examine the title again, this time on an interpretive level. Answer your questions. Figure out how the title illuminates the poem. Remember a "naming title" may not mean much. Remember you can do this with the first line of a poem if it lacks a title or you can skip this step altogether. Theme (NOT A MORAL!) After identifying a subject/topic of the poem, determine what the poet thinks about the subject. What is the poet saying about life? Remember, it cannot be a command (no bossing the reader). Theme: Imagination can be powerful. Moral: Let your child daydream. Sample paraphrase—no figurative language allowed—and no big words! I enjoy seeing it drink up the miles and use its tongue to consume the valleys. Then it pauses to eat at a watering tank. After that it takes a gigantic step around some mountains while haughtily peeking into some crudely built huts on the roadsides. It slices through an open pit of rocks just enough to squeeze itself through. It complains constantly with a repetitive sound and then speeds down the hill, making a thunderous noise. Right on time it stops, nicely and powerfully, at its shed. Sample connotation—analyze! “I Like To See It Lap the Miles” is an extended metaphor because the train is compared to a horse. In fact, train engines were referred to as “iron horses,” which is probably where Dickinson got the idea for this poem. The feeding tanks are the water and coal needed to fuel the engine, the complaints and neighs are the sounds a train makes as it goes up and down hills or toots its whistle. The “stable door” is the station. In order to make the engine seem like a living creature, Dickinson uses personification. A train engine does not have a tongue, so it can’t “lap the Miles” or “lick the Valleys up.” It doesn’t have a mouth or stomach, so it could not “feed itself at Tanks.” The language gives the engine many attributes of a horse: mouth, stomach, eyes, legs, and vocal chords. Dickinson also uses an allusion in the phrase “neigh like Boanerges.” Boanerges means “son of thunder” and is what Jesus called James and John, the sons of Zebedee, in the New Testament. Besides imagery, the poet uses sound devices. The second and fourth lines of each verse either rhyme or have near rhyme: “up” and “step,” “Star” and “door.” The entire poem is iambic, with the first and third lines in tetrameter and the second and fourth lines in trimeter. Dickinson also uses alliteration: “like to see it lap” and “horrid—hooting.” Sample attitude The speaker of the poem seems to be a child with a good imagination. Many of the words are simple, though “supercilious,” “prodigious,” “Boanerges” and “omnipotent” require most people to find a dictionary. Still, a child growing up in a religious household in the nineteenth century would have been familiar with these words. The speaker may have been describing this scene to a friend or to a parent—or may have simply been wondering aloud. Sample shift The poet uses "then" four times. Each time the train stops what it has been doing and begins another activity. This is similar to the many stops a train makes during the day. In fact, steam engines had to stop every seven miles, which is why so many towns in rural areas are only seven miles apart. Sample theme The theme seems to be the power of imagination or wonder of a child. Just as the speaker is able to compare a steam engine to a horse, children have the capability of pretending that one object is really something else.