Movement in Japanese Bunraku and Kabuki Theatre

advertisement

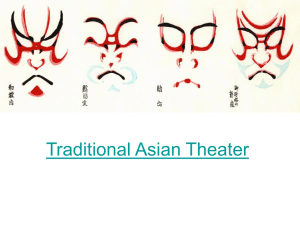

Kaitlyn Wren THEA4400 Richmond Objective: to take a comparative look at how the movement styles of the Bunraku and Kabuki theatres were mutually influenced through their competitive, interdependent historical development. The intricacy of the relationship between these two art forms can be seen in the degree of the stylization of movement. This form of puppet theatre was originally known as Ningyo-shibai, or “doll-theatre” It is known today as Bunraku because of the revival of the doll-theatre from the Bunraku-za of Kyoto It is a product of collaboration of three aspects: 1- joruri: the narration of the text in a stylized form of chanting 2- the accompanying musical styles of the twang of the samisen 3-ningyōtsukai: the skillful life-long training of puppet manipulation More chanter-centered: the audience goes to the theatre to mainly hear the tayū (chanters) perform their skillful portrayal of the texts Literal meaning “off beat” This theatrical art form developed out of the lower class. There is a general motif of erotic love and its history is generally acknowledged with prostitution It is known for being grandiose in nature. Large scale: This term encompasses the concepts of (“ka”) song, (“bu”) dance, and (“ki”) skill stylized makeup, outlandish costuming, and extravagant movement, colorful music, sculpture-like poses, and rigidly choreographed fighting much of kabuki was taken from puppet theatre, so the gestures are much like them, just on a larger scale Actor-centric: the audience generally flock to see the expertise and precision of the actor As the histories of these two art forms show, they were in constant competition for favor among the Japanese audience. This battle naturally paved the way for an overlap of textual content, musical chanting style, and movement technique. The Keicho Era (1596-1614): The History of Kabuki can be attributed to a woman, O Kuni, a ceremonial dancer from the great Izumo Shrine. About the eighth year O Kuni performed her historical dance on a river bed that lead to the ignition of popularity for the artfrom and to her creating the first school of Kabuki. At this time the performers were mostly women, 1629- The Shogunate bans Women from the stage and Wakashu (young Men’s Kabuki) takes precedence. 1652- Wakashu suppressed by Shogunate and Kabuki was forced to change from its primarily erotic draw In this same year the inclusion of the rhythmic movement from the influence of doll theatre began to trickle onto the Kabuki stage Genroku Era (1688-1703): Golden Era of Japanese Culture Older men took on all of the roles (male and female) to decrease eroticism of the performances The distinct form of Kabuki began to develop and it started to become a highly respected art form Development of schools of Kabuki and time of Danjuro I Similar to Kabuki, the roots of the Doll-theatre were known as something low and vulgar (Kincaid) The rise of puppet theatre as its known today came out of the eventual fusion of the nomadic puppeteer with the music of the samisen in the late 16th century that became known as the popular music-ballad drama known as Joruri (Kincaid) Edo-period (1603-1868): Doll theatre existed prior to the formation of the Kabuki, but it was not until the early years of the Kanei Era (1624-43) that puppets had a permanent stage. 1684: Development of the theatre Takemoto za in Osaka by Takemoto Gidayu in collaboration with Japan’s most famous playwright Chikamatsu Monzaemon For the next 80 years, fame of puppet theatre completely eclipsed that of Kabuki During these 80 years, due to the overwhelm of Bunraku influence, Kabuki developed similar technique of production actors emulated movements and gestures of the dolls Thematic substance for the plays began to overlap The overall concept of realism previously attributed to Kabuki now merged with the stylization of the puppet theatre in production and movement “How the doll-actors took their rise, how for them the best theatre talent of the land was concentrated, and how these gorgeously costumed puppets of wood, animated by pulleys and strings, influenced the actors of flesh and blood, forms a unique chapter in the history of the Japanese theatre.” (Kincaid p. 144) “The movements of the dolls were so spirited, the doll-handlers so creative in the variety of gestures that they invented to express a whole world, gay and grave, that the actors came at last to acknowledge the puppets as a source of inspiration.” (Kincaid 149) The Yedo actors of Kabuki had to venture into the Kyoto and Osaka theatre in order to understand how to play the characters of the en vogue doll theatre plays. An example of the extreme interdependence of the two forms can be illustrated by the story of the famous puppeteer and puppet costumer Bunsaburo. It is said that one evening in the puppet theatre, when the audience was scattered with Kabuki artists, one of the puppets was one the verge of falling over in mid performance. Bunsaburo quickly came to its rescue and as he did so, the puppet moved in an awkward fashion that was different than that of regulatory movement and the audience broke into laughter. From then on, this became the norm for this particular puppet production. Very soon after, down the street in the Kabuki theatre, the actors were seen portraying the same characters, in the same costumes, imitating this same awkward falling style. In 1757, prior to the first year of Horeki, the doll theatre was at its height. However, after this, it began its decline. Bunraku gradually diminished by the end of 1770s with the death of some of the best narrators, playwrights and puppeteers. Although Bunraku flourished during the Meiji period (1868-1912), it experienced difficulties in the early part of the twentieth century and during the war years, and it lost public interest. However, Bunraku revived remarkably over recent decades with a growing younger audience. Bunraku is once again a popular form of entertainment in Japan and performs to soldout crowds. (4) “The principle of movement in Kabuki is that if at any moment it were photographed, the result would be a charming and pleasing picture.” (5 p.191) Kabuki moves from pose to pose, or from “tension to tension” through the fluidity of time. Aside from the dance element which is present in virtually all of Kabuki, there are three prime elements of movement that make the spectacle of Kabuki more effective and to increase its variety of actionpossibilities. These are: pantomime human imitation of the puppets and the pose. (5) Pantomime It is part of the straight drama of Kabuki Is known as “dumb show” in that is makes little since aside from the addition of beauty and spectacle At the end of the pantomime sequence the starring male role makes his grand exit called roppo or (“six directions” movement by Danjuro I) as he makes his exit down the hanamichi to the back of the theatre. (5 p.186) On a comparative note: This is something that can obviously not be replicated in Bunraku because it would destroy the spectacle. The fantastical gestures of pantomime are known as “living pictures.” The overall effect heightens the decorous fashion of the Kabuki theatre and of Asian artistic appreciation in whole. Imitation of Puppets “The large proportion alone of plays of basic action of the actors must be influenced by puppet styles of movement.” (5 p. 190) In these puppet action plays, there is always a narration and music (similar to the Bunraku) that frees the actor to move and take on the puppet-like motion. There is often the motif of flash back or monogatari (“Narration”) where the actor announces “I will now tell you a story” that allows the audience to know that a narration is to begin. The actor then uses puppetlike gestures and poses to tell the story. (190) Toyata Monogatari- as he begins to tell his story, all semblance of human action dissolves into the irregular and jerky movements of a puppet. “to accentuate the effect, another actor, dressed in black like an old fashioned puppeteer, appears on the stage and goes through the simulated motions of manipulatipulating the human “puppet”’. (5 p.190) Kabuki dance also does not fall under our idea of constant fluidity. Instead, it is constantly moving from tableau to tableau. The basis of all Kabuki is dance, and an actor must undergo extensive training in this area in order to rise in the strict hierarchical system, and shosagoto are generally made up of a combination of mai, a circling movement with the heels kept close to the floor, odori, folkinfluenced gestures and turns, and furi, use of mime often involving props such as fans. kabuki dance – “buyo”- has some elements taken from both Noh and Bunraku forms Kabuki dance cannot be understood within the rigid framework of our western thinking. Our idea of dance typically involves the concept of purely representational movement, however, Kabuki dance lies somewhere along the spectrum of representational movement and true realism The different genres of Kabuki literature clearly call for different forms of movement. Jidaimono: history plays Usually set in historical periods like the Heian Period(794-1185) or the Kamakura Perio (11851336) Often depict times of civil war between Heike and Genji clans of the late 12th century The use of the historical distance allowed the Kabuki theatre to avoid censorship by the Shogunate through depicting war heroes, samurai, lords, princesses, and empresses Sewamono These were the plays of the common people Came out of the period surrounding 1679 when Chikamatsu Monzaemon was at his writing prime. He wrote for both the Kabuki and puppet theatre. This genre depicts low level characters of premodern Japanese society such as prostitutes, shopkeepers, firemen, and the like The plays generally involve conflict derived from either giri (duty vs. family) or ninjo (human emotions). The Love Suicides at Sonezaki falls under this category The styles of the plays call for two main kata or “forms” of movement that are used to play character types in Kabuki. They are: aragoto, or rough stuff, and wagoto, soft stuff. Aragoto characters Typically they are the superhero and warrior types seen in jidaimono They are recognized by their distinctive kumadori make-up, painted in stripes of red, black and blue on the face, arms and legs. The aragoto actors perform with powerful exaggerated voices that resemble bellowing and braying their often nonsensical lines. Their wigs and costumes are just as overscaled, and include padding in order to enlarge the actor’s physical presence. Ichikawa Danjuro I (1660-1704) was the first known aragoto actor An excerpt from the Yoshitsune Senbon Zakura. It was originally written for the puppet theatre in 1747 and premiered in the Kabuki theatre the following year. It is an example of the jidaimono genre on of the stylized choreography that accompanies the fight scenes. Along with the concept that Kabuki is actor-centric, the actors were the primary directors and choreographers. This video also shows the difference between Kabuki and Bunraku performance scale. From this audience member’s viewpoint, they would not be able to read this amount of detail into a Bunraku performance that can be seen in this grandiose Kabuki performance . Wagato characters are the foil of the aragoto characters. They are often played by onnogata (“women roles”) They are sensitive and romantic and the movement is vastly more understated than that of the aragoto. This type of movement exemplifies emotion Sakata Tojuro I (1647-1709) is credited with the development of this kata This is an example of the wagato, “soft stuff” acting style that is found in the sewamono genre. This is a clear depiction of the “onnogata” (woman role) Just as kabuki took from the doll theatre form, we can conversely see how the doll theatre also took on the gestures and style of living actors, modeling their specialties, young women, heroes, heroes and villains. This video provides the doll theatre’s take on femininity as a contrast to that of the previous Kabuki video. It also provides a beautiful example of the puppet depiction of grief. The concept of stillness is incredibly powerful in the theatre, especially of these two forms where the stylized movement is so visually alluring. The contrast of stillness in Bunraku and Kabuki is striking. Kott states that the most difficult task for actors is to embody stillness and silence on stage. Conversely, when the puppets are left alone by their puppeteers, they are frozen in immobility. This simple concept allows the effect of sorrow and woe to be isolated within the moment and within the seeming lifeless body of the puppet corpse. “One of the puppets' most profound effects is their posture at rest. When communication along a marionette's strings is halted, the figure simply goes limp. It appears to have fallen into a primeval quiet. Since the Bunraku doll's connection to its handlers remains uninterrupted, the puppet never reaches that point. A human hand and mind are actively involved in the stillness, thus it is calculated, more akin to a held breath. This elegant maneuver in particular conveys a haunting implication of Bunraku: Someone, or something, is always watching.” (Jacobs) The use of stillness in the Kabuki theatre is likewise effective. For example, the aragato performance includes the renowned mie. The mie is the highly stylized pose that absorbs the central meaning of the particular character in the height of emotion. The phrase that accompanies this action is mie o kiru, or to "cut a mie." The moment is intensely built up. Wooden clappers are beaten and the actor performs grandiose movement, a dramatic head roll, then they are entirely frozen in a statuesque pose with one or both eyes crossed. Often it's preceded by a head roll. The idea is to capture the highest moments of tension into one physical gesture and to more or less hold the actor and the audience in a breathless trance. After a few seconds, the actor relaxes and the play continues. A mie can be cut in various specified positions, depending on the character and the moment. When exiting, an aragoto character may perform a roppo exit, which combines several of these poses in rapid succession, before leaving the stage. The mie is not a realistic pose, but rather it is “a static attitude preceeded by increasingly rhythmic movement which reaches an equilibrium in this pose…its essential quality is that of balanced, sculptural tension.” Depiction of mie (in real time the actors are just about this still. When watching it on video I though my computer froze when the actor cuts a mie. But it is just an example of the utter skill in discipline and sheer control of every fiber of one’s being into the frozen display of character.) Omozukai-head and left arm operator Hidarizukaiassistant who manipulates right arm Ashizukai- third handler who operates feet Yet another illustration of the triune puppet manipulation system. A depiction of the mechanics of puppet facial expression. Though much of the spoken information is redundant with the rest of this presentation, this video provides an excellent view of the mechanics of puppetry in creation and action. “Those stately moves, those yowling falsetto voices, those delectably coloured sets of wisteria-clad teahouses or cedar-strewn mountains, above splendid origami outfits and hairdos - they turn the human being into an esoteric puppet on divine strings.” Ismene Brown “The piece depicts a love affair between the 19 year old courtesan Ohatsu and the 25 year old clerk Tokubei. They commit suicide to be united in death. It's a love story, emblematic of Kamigata kabuki, which emphasizes realism. The affair ending in shinju (double suicide) is a romantic ideal in Japan.” For your entertainment pleasure, I found an additional puppet video. Though this is not the typical manner in which Bunraku is performed, I thought it was an absolutely exquisite display of bringing a puppet to life.