Periods_Arabic_Poetry

advertisement

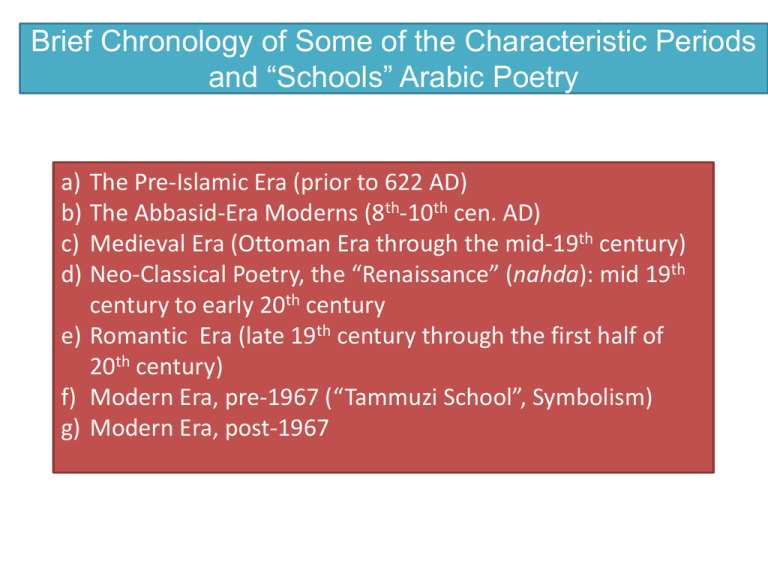

Brief Chronology of Some of the Characteristic Periods and “Schools” Arabic Poetry a) The Pre-Islamic Era (prior to 622 AD) b) The Abbasid-Era Moderns (8th-10th cen. AD) c) Medieval Era (Ottoman Era through the mid-19th century) d) Neo-Classical Poetry, the “Renaissance” (nahda): mid 19th century to early 20th century e) Romantic Era (late 19th century through the first half of 20th century) f) Modern Era, pre-1967 (“Tammuzi School”, Symbolism) g) Modern Era, post-1967 Pre-Islamic Era (before 622 AD) • • • • • Formal qasida structure (rhyme, meter, hemistichs) Formulaic thematic structure Oral composition and transmission Poet articulates a collective identity Poems address specific event or occasion, already known to audience • Poetry serves a vital function: praise, boast, invective, mourning, etc. • Repository of Arabs’ knowledge (history, geography, society, etc.) The Abbasid-Era Moderns (8th-10th cen. AD) • • • • Maintains formal requirements of traditional qasida Clear, lucid diction Thoughtful interaction of form, language and meaning News ideas expressed, some of which subvert conventional themes and topics of Arabic poetry • Both sentimental and “occasional” (ie, event based), yet always thought provoking. • Abu Nuwas, Abu Tammam, al-Ma’arri, etc. “Conventional” Classical/Medieval Poetry, (Ottoman Era to mid-19th century – “The Era of Literary Decadence”) • Strict maintenance of formal requirements • Complicated word-play, verbal virtuosity, obscure vocabulary • Poetry written for and by the cultural elite; “an exercise of wit” (Jayysui, p. 1) • Conventional topics (primarily praise poems) or detailed – nearly microscopic – descriptive poems • “[neglect] for the existential dimensions of the human condition” (Jayyusi, p. 1) Neo-Classical Poetry, the “Renaissance” (nahda): mid 19th century to early 20th century • Inspired, somewhat, by perceived gap between Western political, military, technological, and cultural progress and Arab cultural, political, etc. “stagnation” • Awakened interest in Arab poetic heritage; reinvigorate traditional poetics • Maintenance of classical-era, formal requirements (rhyme, meter, hemistichs) • Rejection of obscure and overwrought lexical and metaphoric diction • Address topics pertinent to the lived existence of modern (19th-early 20th century) Arabs • Political content; at times critical of authorities (political and religious), yet never “revolutionary”; renewal, not rejection, of indigenous social and political systems • Balance between form and function, beauty and clarity, emotion and reason; strong, clear, and direct oratorical style • Ahmad Shawqi, “Prince of the Poets” Romantic Era (late 19th century through the first half of 20th century) • • • • • • • • • Took root amongst Arab poets living abroad (in the US/NYC and South America) – the mahjar (“ex-pat community”) Inspired from Western romantic-era poetry and American transcendentalism (Walt Whitman, for instance), and adapted themes and ideas from non-Arab sources Dissatisfaction with conventional formal requirements of Arabic poetry (uniform meter, uniform rhyme, hemistich line structure); rejection of “sterile” and “moribund” conventions Emphasis on emotional world of the poet, rejection of material, Earthly matters – poetry a reflection of the poet’s soul, not his corporeal state Deeply sentimental, dealt with existential matters (often in a heavy-handed manner); unremittingly sincere and earnest Imbued with spiritualism and contemplation, “Eastern spiritualism” vs. “Western materialism”; a yearning for spiritual transcendence, often expressed through the metaphoric language of the lover and beloved. Diction that is “modern, elegant, and original”; “imagery that was evocative and imbued with a healthy measure of emotion (Jayyusi, p. 5). Revolutionary in its confrontation of social taboos; not, however, overtly political. Strong advocacy for women’s rights. Khalil Gibran, Mikha’il Nu’ayma, Amin al-Rihani (all based in NYC, originally from Lebanon) Modern Era, pre-1967 (“Tammuzi School”, Symbolism) • • • • • • • Outright rejection of formal strictures of the qasida: no more unifying rhyme, no more unifying meter, no more hemistich lines (The Free Verse Movement – Nazik Mala’ika) Addresses present through Islamic and Near Eastern mythological motifs (inspired by Frazier’s The Golden Bough to look for primordial themes that undergird all human experience) Consciously experimental; “The directness, rationality, and traditionalism of the neoclassical school were transcended, as were the dilution, flabbiness, sentimentality and spleen of Romanticism” (Jayyusi, p. 7) In dialogue with Western literary theory and poetic models (T.S. Eliot, Yeats, etc.); happily draws from a broader human poetic culture – East and West. “Conjured meaning through the musicality of words” (Jayyusi, p. 6), i.e., language integration (see Culler, p. 29); “”calm pace, gemlike selection of words, harmonious compositions, and gentle rhythms” (Jayyusi, p. 11); clarity of language (even if references to mythology or western literary figures remained beyond the ken of casual readers). Topically and thematically fragmented; deliberate opacity evokes sense of disorientation and confusion of Arab world; however, atmosphere of gloom leavened by potential for rebirth and renewal; inspired by the successes of Arab nationalist movements in the face of foreign colonization; “a deep faith in the in the possibility of human struggle to bring about the final triumph of freedom and justice” (Jayyusi, p. 21) Abd al-Wahhab al-Bayati, Adonis, Badr Shakir al-Sayyab Modern Era, post-1967 • • • • • • • • Disillusionment with political condition after failure of the Arab nationalist project under Gamal Abd al-Nasser, continued foreign intervention and local repression; commitment to present affairs; expression of life as lived by all Arabs, not merely privileged classes Thematically grim, a reflection of general pessimism in Arab political affairs after 1948 and 1967: “an atmosphere haunted by feelings of sorrow, disgust, shame, anger, frustration, apathy, and alienation” (Jayyusi, p. 16) Like earlier Modern poetry, text, narrative and narrator are fragmented, and contradictory – a reflection of pervasive “existential malaise”; unlike earlier poets, very little hope for political and social renewal. Ambiguity and irregularity of modern life reflected in poetic lexicon, sentence structure and metaphor (Jayyusi, p. 28) Very few poets maintain formal strictures of the traditional qasida “Poetry…abandoned the songs of weddings and festivals, the prayers of lovers, and the private longings of the soul, in favor of a more communal expression rife with anger and frustration” (Jayyusi, p. 16) – the poet resumes his communal role from the pre-Islamic era? Paradox of social commitment, even as “Arab poetry has delved deeper and deeper into new realms of obliquity and metaphorical adventure” (Jayyusi, p. 16) The Arabic poetic heritage questioned and attacked; indeed, all dogmas and doctrine (including those of language and the poetic traditions itself) become subjects of critique. Nizar al-Qabbani, Mahmoud Darwish, Saleh al-Sabur Modernism in a nut shell “The major attainments of modernist Arabic poetry have been toward complexity and coherence, esthetic sophistication and originality, together with a deep commitment to the cause of human justice and freedom. This has always been poetry’s greatest aspiration, its most arduous task. The success of some major experiments must be seen as phenomenal in view of the fact that it comes on two levels which are not mutually compatible: esthetic complexity and social commitment” (Jayyusi, p. 37).