Mexican Americans - Humanities Texas

advertisement

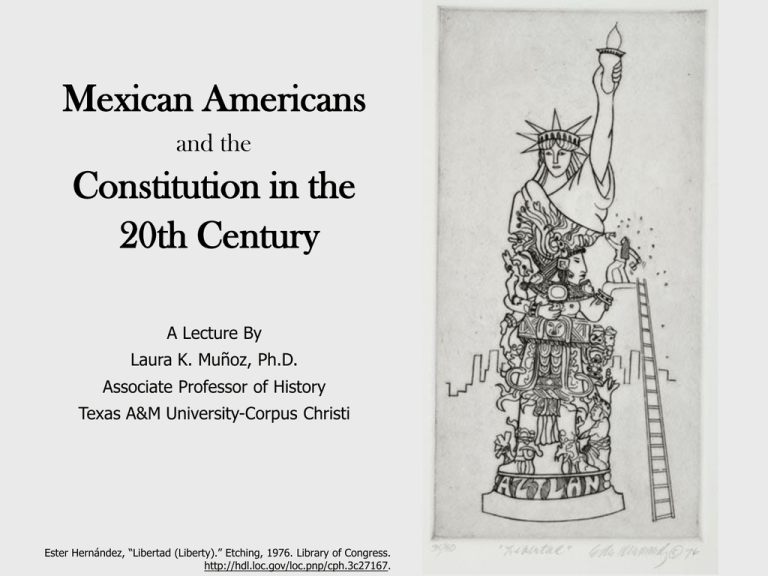

Mexican Americans and the Constitution in the 20th Century A Lecture By Laura K. Muñoz, Ph.D. Associate Professor of History Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi Ester Hernández, “Libertad (Liberty).” Etching, 1976. Library of Congress. http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/cph.3c27167. 1st Amendment Freedom of Speech, Press, Religion & Petition Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances. 14th Amendment - Citizen rights not to be abridged Passed by Congress June 13, 1866. Ratified July 9, 1868 1. All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor to deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws. Relevant TEKS 1. The Celebrate Freedom Week standard, and 2. 11th-grade U.S. History standards, specifically (c)(9). (c)(9) History. The student understands the impact of the American civil rights movement. (A) trace the historical development of the civil rights movement in the 19th, 20th, and 21st centuries, including the 13th, 14th, 15th, and 19th amendments; (B) describe the roles of political organizations that promoted civil rights, including…Chicano…civil rights movements; (C) identify the roles of significant leaders…Hector P. Garcia;… (I) describe how litigation such as the landmark cases of…Mendez v. Westminster…Delgado v. Bastrop I.S.D., Edgewood I.S.D. v. Kirby…played a role in protecting the rights of the minority during the civil rights movement. Phoenix, Arizona December 22, 1915 "Segregation of Mrs. Luther Stover Williams, Arizona School Children. Dear Mrs. Stover: Mexican Children Not Embraced in Segregation Law." Biennial Report of the Attorney General of Arizona, 1915-1916 Your letter of December 30th, addressed to the Attorney General has been received, in which you ask whether or not Mexican children can legally be segregated from the white children in the public schools. In reply thereto will say that Subdivision 2 of Paragraph 2733, Revised Statutes of Arizona, 1913, in prescribing the powers and duties of the Board of Trustees of School Districts, provides: "...They shall segregate pupils of the African race from pupils of the white race, and to that end are empowered to provide all accommodations made necessary by such segregation." You will therefore see that our law empowers trustees to segregate children of the African race, but does not empower the trustees to segregate children of the Mexican race unless, of course, children of the Mexican race might also be of African descent, by being intermingled with African blood through birth. I am therefore of the opinion that we have no law empowering trustees to segregate Mexican children from white children in our public schools. Very truly yours, GEORGE W. HARBEN Asst. Attorney General Sign painted on exterior restaurant wall… “We serve Whites only No Spanish or Mexicans,” 1949. Source: Courtesy of Center for American History, University of Texas, Russell Lee Photograph Collection, 1935-1977. “You would go and sit down in a restaurant that didn’t have the sign…and they would come and tell you: ‘We don’t serve Mexicans here.’ Those were the conditions we were fighting. You couldn’t go to barbershops. You couldn’t go to an Anglo theatre.” John C. Solís, founder Order Sons of America Source: Quoted from Cynthia E. Orozco, No Mexicans, Women or Dogs Allowed (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2009). Alameda Theater, San Antonio. Source: Center for American History, University of Texas, Russell Lee Photograph Collection, 1935-1977. “I found conditions worse that [sic] those in San Antonio. There [in Corpus Christi] they had a Mexican school. You couldn’t eat in the Anglo restaurants. You couldn’t bathe in North Beach because you were a Mexican. There were signs that said: ‘No Mexicans allowed.’” John C. Solís, founder Order Sons of America North Beach, Corpus Christi, Texas, circa 1930. Source: McGregor Digitized Photograph Collection, Corpus Christi Museum of Science and History. Source: Quoted from Cynthia E. Orozco, No Mexicans, Women or Dogs Allowed (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2009). A Sampling of Early 20th-Century Mexican American Civil Rights Groups Includes mutual aid associations (mutualistas), social clubs, and unions. Name Locations Founding Concerns Date 1 Alianza Hispano Americana AZ, CA, CO, NM, 1898 TX, Old Mexico 2 Masons (such as Logia Masónica Benito Juárez) TX 3 Orden Caballeros de Honor y los TX Talleres (Order Knights of Honor) 1911 Fraternal 4 U.S. National 1911 Fraternal 5 Woodmen of the World (WOW, Los Leñadores del Mundo or Los Hacheros) Gregorío Cortéz Defense Network TX 1906 Legal Defense Committee 6 Agrupación Protectora Mexicana TX 1911 Lynchings 7 Primer Congreso Mexicanista TX 1911 Lynching 8 Liga Femenil Mexicanista TX 1911 Education, Volunteerism 9 Liga Protectora Mexicana Tx (Austin) 1917 Working Poor People 10 Order Sons of America (Orden Hijos de América) TX (San Antonio) 1920 Civil Rights 11 Club Protector México-Texano TX (San Antonio) 1921 Civil Rights 12 Order Sons of Texas TX (San Antonio) 1921 Civil Rights Life Insurance, Civil Rights Fraternal Source: Cynthia E. Orozco, No Mexicans, Women or Dogs Allowed (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2009). “South Texas map showing the Order Sons of America and League of Latin American Citizens councils, 1920s.” Source: Cynthia E. Orozco, No Mexicans, Women or Dogs Allowed (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2009). Mexican American School Desegregation Cases, 1925 to 1983 Source: Reprinted from Richard R. Valencia, Chicano Students and the Courts: The Mexican American Legal Struggle for Educational Equity (New York: New York University Press, 2008). Limited School Curricula Housekeeping Basic education for Mexican American girls emphasized homemaking and domestic skills. Tempe Normal School Bulletin, ca. 1915. Cookery Class Limited School Curricula Gardening Mexican American boys learned subsistence skills, such as farming and carpentry. Tempe Normal School Bulletin, ca. 1915. Woodshop Courtesy of Arizona State Archives, Phoenix. Separate Schooling Segregated Class, Gilbert Public Schools, Eastern Phoenix Metro Area, Arizona, circa 1920s Courtesy of Arizona State Archives, Phoenix. Separate Schooling “1st and 2nd Mexican, Miss Goldie Olsen, teacher. 1923” Peoria School District #11, Western Phoenix Metro Area, Arizona Courtesy of Arizona State Archives, Phoenix. Separate Schooling – “Mexican Schools” Segregated School, Twin Cities of Ray and Sonora, Arizona Romo v. Laird (1925) The first Mexican American school desegregation case Separate Schools Conditions “Modern Brick Structure,” at South Edcouch Elementary (Anglo). Note concrete foundation. “Old Army Barracks” at Elsa Elementary School (Mexican American). Note pier foundation. Source: Richard R. Valencia, Chicano Students and the Courts: The Mexican American Legal Struggle for Educational Equity (New York: New York University Press, 2008). Separate Schools Conditions “Indoor Drinking Fountain with Electric Cooler,” at South Edcouch Elementary (Anglo). Note indoor plumbing. “Outdoor Drinking Fountains” at North Edcouch Elementary School (Mexican American). Source: Richard R. Valencia, Chicano Students and the Courts: The Mexican American Legal Struggle for Educational Equity (New York: New York University Press, 2008). Source: Richard R. Valencia, Chicano Students and the Courts (New York: New York University Press, 2008). “Shields on Bulbs for Diffused Lighting” at South Edcouch Elementary (Anglo) “Bare Bulbs” at North Edcouch Elementary (Mexican American) Separate Schools Conditions Mathis High School, Mathis, Texas, circa 1946. “Mexican Ward Schools,” Mathis, Texas, circa 1946. Source: Richard R. Valencia, Chicano Students and the Courts: The Mexican American Legal Struggle for Educational Equity (New York: New York University Press, 2008). Mendez v. Westminster (1946) The first successful challenge to Mexican American school desegregation. Goal: To end statewide school segregation of Mexican American children. School districts argued that segregation was language based. The court ruled segregation violated the “guarantees of equal rights under the 14th Amendment.” Sylvia Mendez received the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2010. Source: “O.C. civil rights icon Mendez awarded Medal of Freedom,” OC Register, 15 February, 2011, accessed at http://www.ocregister.com/articles/mendez-288377-medal-case.html; Delgado v. Bastrop ISD (1948) “Delgado was to Texas as Mendez was to California: the goal in both cases was to bring an end to statewide school segregation.” – Dr. Ricardo R. Valencia. Bastrop “Mexican school,” a single story, wood frame building with makeshift “privies” attached to back of building. Sources: Richard R. Valencia, Chicano Students and the Courts: The Mexican American Legal Struggle for Educational Equity (New York: New York University Press, 2008); Digitization of the photographs from the George Isidore Sanchez Papers, University of Texas at Austin, available at http://www.lib.utexas.edu/photodraw/sanchez/inde x.html. Delgado v. Bastrop ISD (1948) Mexican school, outdoor drinking fountain. Two-story, brick building for Anglo children. The War Against Racial Prejudice Gonzales v. Sheely (1951) TX attorney Gus García, AZ attorney Ralph Estrada, UT-Austin professor Jorge Ramírez; Lauro Montaño of Alianza Lodge #52 Los Angeles; Arturo Fuentes and J. I. Gandarilla, Alianza supreme president and Alianza supreme vice-president; and Fred Okrand, ACLU attorney from Los Angeles. Source: Alianza Magazine, Vol. XLV, No 4 (April 1952), 5. Edgewood ISD v. Kirby (1984) tackled funding disparities between property-rich and property-poor school districts, and the effect of this difference on educational quality. School districts are funded through collected property taxes. Disparities emerged as a result of property values. The Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund (MALDEF) sued state commissioner of education William Kirby on behalf of Edgewood ISD in San Antonio, Texas. The case was preceded by Rodriguez v. San Antonio ISD (1971). Source: Richard R. Valencia, Chicano Students and the Courts: The Mexican American Legal Struggle for Educational Equity (New York: New York University Press, 2008) Edgewood ISD v. Kirby (1984) The disparities… Example 1 : In 1985-1986, the difference between funding per pupil in Texas schools ranged from $2,112 to $19,333. Example 2: The richest Texas school district had over $14M in property wealth PER PUPIL, while the poorest district had $20K in property wealth PER PUPIL (a 700:1 ratio). Initially the court ruled in Edgewood’s favor, deciding: a) Education is a fundamental right. b) Wealth is a suspect classification. c) Texas’ school finance scheme is unconstitutionally inefficient. d) The Constitution of Texas demands fiscal neutrality in the funding of public schools. Source: Richard R. Valencia, Chicano Students and the Courts: The Mexican American Legal Struggle for Educational Equity (New York: New York University Press, 2008) Edgewood ISD v. Kirby (1984) - The final verdict The Court of Appeals of Texas reversed the “Edgewood 1” ruling. The court challenged the Equal Protection (14th Amendment) analysis used by the lower court and disagreed that “education is a fundamental right under the Texas Constitution.” The Texas Supreme Court, however, reversed the Court of Appeals decision on two points in particular: a) School funding disparities. “Property-poor districts were ‘trapped in a cycle of poverty’ from which there was no opportunity to escape.” b) An efficient school system. “The Texas Constitution required an ‘efficient,’ not ‘simple’ or ‘cheap’ public school system. The framers of the state’s Constitution did not intend a school system with huge funding disparities, but rather a system that provided a ‘general diffusion of knowledge.’” Source: Richard R. Valencia, Chicano Students and the Courts: The Mexican American Legal Struggle for Educational Equity (New York: New York University Press, 2008) Conclusions Mexican Americans have engaged the Constitution, particularly the 1st and 14th Amendments, to secure equality in America. Their civil rights efforts began in the late 19th- and early 20th-century, suggesting a consistent and “long civil rights movement’.” They established national and statewide organizations such as the Order Sons of America (in addition to LULAC, the American GI Forum, and MALDEF) to challenge inequality, especially “segregation” in public life and in the public schools. Once segregation was outlawed, they continued to challenge economic inequities affecting their children’s educational access and opportunity. Mexican Americans and the Constitution in the 20th Century Contact Information: Laura K. Muñoz, Ph.D. Associate Professor of History Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi 6300 Ocean Drive, Unit 5814 Corpus Christi, TX 78412-5814 laura.munoz@tamucc.edu (361) 825-3975 Acknowledgements: Thank you to Humanities Texas and the Education Service Center, Region 2. I appreciate the time, energy, and courtesy you have shown me. I owe special thanks to the Department of Humanities, College of Liberal Arts at Texas A&M UniversityCorpus Christi, and the following individuals: Eric Lupfer, Rachel Spradley, and Natasha Crawford.