NewIntrotoBhagavadGita

advertisement

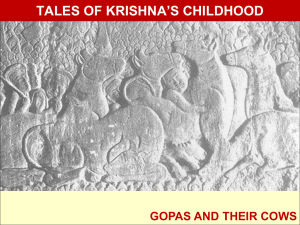

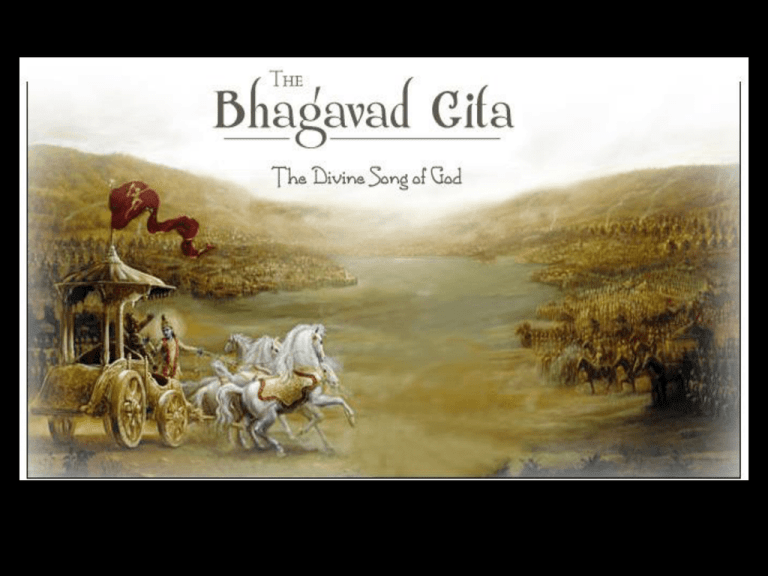

The Bhagavad Gita is a part of a larger text called the Mahabharata. At 200,000 verses (1.8 million words), the Mahabharata is about ten times longer than Homer’s Illiad and Odyssey combined, and three times the length of the Christian Bible. Mahabharata: An epic tale of war between the Kauravas and Pandavas, rival factions of the royal Kuru family in India. Date of the Mahabharata War: Perhaps as early as the 3138 BCE; maybe as late as the 9th century BCE. The written text of the Mahabharata epic originated around the 6th century BCE. Authorship is traditionally given to seer Vyasa, who is also a character in the story. The Seer Vyasa Date of the Mahabharata War: Perhaps as early as the 3138 BCE; maybe as late as the 9th century BCE. Some western scholars have argued that the Gita may have been added to the Mahabharata at a later date, but the text is most likely no later than the 2nd century BCE and grounded in an older oral tradition. The Seer Vyasa The Mahabharata War The seer Vyasa (traditional author of the Mahabharata) was the father of Prince Pandu, who became the emperor of Hastinapur near the end of the 4th millennium BCE. Pandu was appointed ruler instead of his brother Dhritarastra because Dhritarastra was born blind. However, after accidentally killing a sage and his wife while love making, Pandu renounced his royal status, handed over his kingdom to his blind brother Dhritarastra, and retired to the forest to live as an ascetic with his two wives Kunti and Madri. Dhritarastra Through his two wives Pandu became the father of five sons: Nakula, Bhima, Yudhisthira, Arjuna, and Sahadeva. After Pandu’s early death, Kunti brought the boys back to Hastinapur where they were raised by Dhritarastra. All of the boys were trained as warriors (ksatriya). The Pandava boys were raised together with Dhritarastra’s sons (the Kauravas) but their relationship was tense and marked by increasing hostility. Duryodhana (Dhritarastra’s ruthless son) was especially hateful of the Pandavas and jealous of their popularity from his youth. Under pressure from the people, Dhritarastra appointed Pandu’s son Yudhisthira as prince. Filled with rage, Duryodhana began plotting the death of the Pandavas. After a failed attempt at burning the Pandavas alive, the Pandavas fled to the forest and Dhritarastra crowned his son Duryodhana as prince. Dhritarastra eventually divided the kingdom, retaining Hastinapur for himself and his son, and giving the Pandavas an undeveloped part of the territory (Khandavaprastha), which the Pandavas developed into the great city Indraprastha (modern day Delhi). Duryodhana was again enraged at the prospects of sharing the kingdom with the despised Pandavas and plotted to acquire their half of the kingdom. With assistance from an evil uncle (Shakuni), Duryodhana tricked Yudhisthira to wager the Pandava kingdom in a series of dice games that Duryodhana rigged to guarantee that Yudhisthira would lose. Yudhisthira lost the games and forfeited his kingdom, wealth and his wife (Draupadi). Yudhisthira The Pandavas accepted their defeat and were sent into exile in the forest for 13 years. According to the terms of their defeat, they would regain their kingdom after 13 years. However, after 13 years Duryodhana denied the Pandavas the kingdom that was rightfully theirs. Duryodhana: “If they want as much land as fits under a pin, they will have to fight for it.” The Pandava-Kaurava conflict quickly escalated in the direction of inevitable war. The Justification of the War Six Specific Crimes Attributed to the Kauravas • Administering poison Duryodhana attempted to kill Bhima by feeding him poisoned cake. • Burning the homes of others Duryodhana burned down the Pandavas’ large residence while the Pandava family inside. • Theft • Illegal occupation of land belonging to others Kauravas stole land from the Pandavas on multiple occasions. • Kidnapping another man’s wife Duryodhana took Yudhisthira’s wife from him after the rigged dice game. • Attacking with deadly weapons The Unjust Rule of the Kauravas In addition to their criminal treatment of the Pandavas, the Kauravas ruled their subjects with harshness and injustice, for example, by imposing unfair taxes to raise money to strengthen their armies. “Just War” according to the Vedas • The Mahabharata depicts the Kauravas as aggressors engaged in crimes (atatayi) that merit capital punishment under the authority of the Vedas. • The Manu-Samhita 8:350-1 states that aggressors who commit the crimes attributed to the Kauravas must be killed to preserve the integrity of the social order. The Warrior Class (Ksatriyas) • The Vedas grant ksatriyas (warriors) the right to carry out punishment for criminal behavior. • The ksatriya’s actions must be in accordance with the moral and social law of the Vedas. • The ksatriya is not a person who instigates harm or injury but one who protects society from harm and violence. The Pandavas attempted peaceful resolution and reconciliation with the Kauravas, but the Kauravas refused and pushed for a military confrontation. Yudhisthira’s attempt at avoiding war is set forth in his powerful speech in Udyogaparvan 70.55-58 of the Mahabharata. Lord Krishna: The Descent of God (Avatara) Krishna, of the Vrishni family (cousin to the Pandavas and Kauravas) had already established himself as a powerful warrior and prince in Mathura, where he had re-established righteousness after destroying the evil ruler King Kamsa and establishing a kingdom in Dwaraka. ★ ★ Krishna befriended Arjuna in Mathura. He had been watching the evolving conflict between the Pandavas and Kauravas. He eventually intervenes to arbitrate the conflict and becomes the focal point of the war. Krishna is revealed to be God manifested on earth, delivering a message of universal salvation. Krishna is one of the most important and widely worshipped deities in the Indian religious traditions. Although the modern worship of Krishna has been strongly shaped by the evolution of devotional theism from the 9th century CE onwards, • ancient texts from Greece provide evidence of the worship of Krishna as a divine being in the 5th/4th century BCE. • archeological evidence for the worship of Krishna dates at least to the end of the 2nd century BCE. In the fabric of contemporary Indian devotional religion (tracing back to at least the 9th century CE), Vaishnavas worship Krishna as an avatar of Vishnu, “Vishnu” (meaning “all pervasive”), one of the names that refers to the Supreme Being. Gaudiya Vaishnavism (early 16th century), along with the sampradayas associated with Vallabha and Nimbarka, regard Krishna as svayam bhagavan (the original form of God) and Vishnu is merely an expansion from the being of Krishna. Textual Sources on the Life of Krishna • Bhagavada Gita (Mahabharata text, circa 400-200 BCE) • Srimad Bhagavatam (Purana literature, 4th-6th century CE) • Harivamsa (lengthy appendix to Mahabharata, 5th century CE) • Vishnu Purana (Purana literature, 5th century CE) * The dates above are assigned for the composition of the texts. The material in the text is generally believed to originate from a significantly earlier period. I. Krishna’s Birth Aware that unrighteousness had spread throughout Bharatavarsha (India) under the influence of evil rulers, Vishnu (the Supreme Being and source of all universes) decided to incarnate himself on earth to destroy evil rulers and restore righteousness on earth. I. Krishna’s Birth So Vishnu incarnated himself in the city of Mathura, which was under the control of the evil ruler King Kamsa. Vishnu decided to take human form as the 8th son of Devaki, the sister of King Kamsa. His name was Krishna – “the all-attractive one.” After being born in Mathura, Krishna was quickly taken to the nearby pastoral town of Vrindavana to escape the murderous plotting of King Kamsa. There he was raised by foster parents Nanda and Yashoda. II. Young Krishna of Vrindavan (Vraj) The Krishna of Vrindavana is a flute playing cow herder who attracts the men (gopas) and women (gopis) of the pastoral town by his playful activities and beauty. Krishna would play the flute and dance with the multitude of gopis along the Yamuna river. They fell madly in love with Krishna. As a youth in Vraj, Krishna sometimes engaged in highjinx, for example, stealing the clothes of the gopis while they bathed naked. The gopis had previously asked the goddess Durga to have Krishna as their husband. Since only husbands were permitted to view a woman naked, Krishna’s high-jinx was a way of his proclaiming that he loved the gopis with conjugal love and accepted them as his own wives. The gopis’ love for Krishna was so great that they cursed brahma (the creator) for creating them with eyes that blinked. Every time they blinked, it was a second in time that they could not look upon the beauty of Krishna. “Their hearts had been stolen by Govinda, so they did not return back when husbands, fathers, brothers, and relatives tried to prevent them. They were in a state of rapture. Some gopis, not being able to find a way to leave, remained at home and thought of Krishna with eyes closed, completely absorbed in meditation.” Srimad Bhagavata, 10.29.9-10 When they were prevented from seeing Krishna because of their household duties, Krishna said: “Love for me comes from hearing about me, seeing me, meditating on me and reciting my glories, not in this way, by physical proximity. Therefore, return to your homes.” Srimad Bhagavata, 10.29.27 Among the gopis, one stood supreme, the particular object of Krishna’s most intense love and devotion – Radha. Radha is depicted as the model devotee, one whose love for Krishna was unrivaled. She thought of Krishna constantly, even in her dreams. Her love was so powerful that it controlled and subjugated Krishna himself. He lost himself so completely in her love that he even forgot that he was God. To signify the depth of their union, they are often spoken of as one God: Radha-Krishna. As an adolescent, Krishna had to leave Vraj for Mathura to destroy the evil King Kamsa. Radha and Krishna part with deep sadness. After Krishna’s departure from Vraj, the gopis search for him with intensity, inquiring of the plants and trees if they have seen Krishna. Their love, like Radha’s, was intensified through separation. The Moods of Vrindavan Krishna • Vrindavan Krishna cultivates diverse moods (rasa) of closeness and intimacy through his many attractive features and activities (rasa lilas), for example: – Friendship: a person relates to Krishna as to a close friend. – Romantic Love: a person relates to Krishna as to a lover. • Krishna’s madhurya qualities form the basis of such moods of intimacy. “Madhurya” means “sweet.” Krishna’s madhurya qualities are his human qualities that attract devotees to a close relationship with him. These qualities are III. Lord Krishna of Mathura and Dwaraka While Vraj Krishna is the playful youth who cultivates moods of intimacy with his devotees, the Krishna of Mathura and Dwaraka cultivates the mood of awe and reverence through the overt display of divine qualities (e.g., omnipotence, omniscience). Krishna’s Godhead was only implicit in Vraj. The Vraj devotees were so attracted to Krishna’s human qualities that they suppressed their knowledge of his Godhead. They regarded his supernatural powers displayed in Vraj as bestowed on him by Narayana (God Vishnu). The Godhead of Krishna is emphasized at Kurukshetra and is a central theme in the Gita text. The Krishna of the Gita is overtly God manifested in human form on earth to reinstate moral order and provide spiritual guidance to humanity. As avatara (“the descent” of God in human form) Krishna manifests madhurya and aishvarya qualities. • Madhurya (sweetness): human qualities that attract and cultivate modes of intimacy • Aishvarya (opulence): divine qualities that instill awe and reverence. Love of Krishna may take various forms: love of intimacy, love of reverence, and love that unites both. Krishna’s Role in the Mahabharata War • Krishna intervenes in the Pandava-Kaurava conflict. • Krishna refused to fight in the war, but he offered himself as charioteer (for one side) and his invincible army (for the other side). • The Kauravas chose to accept Krishna’s army. • The Pandavas chose Krishna himself, even though his role would be confined to guiding the chariot of his cousin and friend Arjuna. Beginning of Bhagavad Gita King Dhritarashtra of the Kauravas requests that his assistant Sanjaya give an account of the clash between the Kauravas and Pandavas at Kuru. Sanjaya proceeds to tell the story, which focuses entirely on a conversation between Arjuna and Krishna as the forces are about to clash on the field of Kurukshetra (“field of righteousness”). Arjuna is first driven to the frontline of the battlefield by Krishna. The chariot halts in the middle of the battlefield, and Arjuna struggles with the moral dilemma of having to fail in his duty as a warrior or kill members of his own family. Gripped by anxiety and despair, Arjuna seeks the advice of Krishna. Krishna assumes the role of Arjuna’s guru and speaks to him Upanishadic wisdom. He leads Arjuna out of his despair to a higher state of consciousness that culminates in Arjuna’s ultimate act of surrender . . . to Krishna himself References • Bryant, Edwin (trans). Krishna: the Beautiful Legend of God, Srimad Bhagavata Purana, Book X. Penguin Books, 2003. • Menon, Ramesh (trans). The Mahabharata : a modern rendering. New York: iUniverse, Inc., 2006. • Prabhupada, A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami. Krishna: The Supreme Personality of the Godhead. Bhaktivedanta Book Trust, 1970. • Rosen, Steven (ed). Holy War: Violence and the Bhagavad Gita. Deepak Heritage Books, 2002. • Rosen, Steven. The Hidden Glory of India. Bhaktivendanta Book Trust, 2002. • Singer, Milton (ed). Krishna: Myths, Rites, and Attitudes. University of Chicago Press, 1966. • Tripurari, Swami B.V.. Aesthetic Vedanta. Mandala, 1998. • Vanamali, Devi. The Play of God: Visions of the Life of Krishna. Blue Dove Press, 1998.