File

advertisement

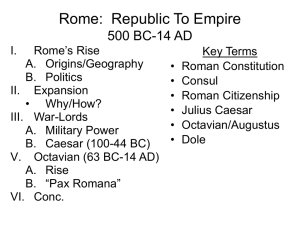

VIRGIL AND THE AENEID Publius Vergilius Maro was born in 70 B.C. at Mantua in Cisalpine Gaul (i.e. the plains of the River Po, which were at that time not regarded as part of Italy). He was the son of a farmer wealthy enough to send him later for education in Cremona, Milan and Rome. A view of Mantua in 1575 and of part of the city centre as it apears today. Although Rome was now mistress of the Mediterranean world, the previous sixty years had seen bitter internal conflict and the year before Virgil was born, a slave revolt led by Spartacus had been put down with great difficulty. During Virgil’s infancy, the political scene was dominated by Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (`Pompey the Great’), who was consul for the first time in the year of his birth. In 67 B.C. Pompey was given extraordinary power to put down pirates then plaguing the Mediterranean and in 65 he gained final victory over Rome’s old enemy, King Mithridates of Pontus in Asia Minor (modern Turkey). In 63 B.C., when Virgil was 7 years old, Cataline,a bankrupt young aristocrat, attempted to seize control of the government but his plans were detected in advanced and thwarted by the consul Cicero, depicted here denouncing him whilst he is shunned by his fellow senators. Julius Caesar was an ally of Pompey in the early 50s, when Caesar began the conquest of Gaul (modern France), but growing tensions between them led in 49 B.C. to civil war, won by Caesar, who became dictator perpetus (`dictator for life’) only to be assassinated in 44 B.C. Brutus and Cassius, leaders of the conspiracy against Caesar, were themselves defeated in the Battle of Philippi in 41 B.C. The victors, Marcus Antonius (`Mark Anthony’) and Caesar’s great-nephew and heir, Octavian (Augustus) confiscated land in Cisalpine Gaul to reward their demobilised troops. Virgil himself may have lost his estate in the process but recovered it afterwards. Virgil’s first major work, completed around 38 B.C., was the Eclogues, modelled on Greek poetry about shepherds and their music-making amidst an idealised countryside, but also including references to the confiscation of farms by Octavian (Augustus) and Anthony after their victory at Philippi. (Illustration from http://www.crystalinks.com/virgil.html) At around this time, Virgil came to the notice of Augustus’s friend Maecenas, who was a generous patron of writers and eager to enlist them in the service of the new regime. Virgil is depicted here standing on the left, with Macenas on the right and two other writers, Horatius (`Horace’) and Varus between them. Despite cooperating successfully to defeat Brutus and Cassius, Octavian and Mark Antony soon fell out. Anthony, like Julius Caesar before him, had become the lover and political ally of Cleopatra, the Greek queen of Egypt. Claiming to be defending Roman values against the decadent East, Octavian declared war on her and defeated Cleopatra and Anthony’s fleet at Actium in 31 B.C. Virgil’s Georgics, a poem on agriculture, probably appeared in 29 B.C. This was two years after Octavian had defeated Anthony and Cleopatra at the Battle of Actium. Although containing much technical information (and therefore hard work to read!), the poem was intended primarily to praise the virtue of a simply country life, which fitted Octavian’s agenda of restoring traditional virtues. Praise of Augustus in the Georgics Dī patriī Indigetēs et Rōmule Vestaque māter, quae Tuscum Tiberim et Romāna Palātia servās, hunc saltem ēversō iuvenem succurrere saeclō nē prohibēte. satis iam prīdem sanguine nostrō Lāomedontēae luimus periūria Troiae; iam prīdem nōbīs caelī tē rēgia, Caesar, invidet Gods of our fathers, local gods, Romulus and mother Vesta, Who guard Tuscan Tiber and the Roman Palatine, At least do not prevent this young man from saving a world Turned upside down. For quite long enough now have we paid The price of Trojan Laomedon’s perjury; For quite long enough, Caesar, has heaven Begrudged you to us. (Georgics I, 498-504) Also in 29 B.C. Octavian (Augustus) began the construction of a full-scale Roman colony – Colonia Iulia Concordia Carthago - on the site of the ancient city, a project which Julius Caesar had envisaged earlier. This dramatic move may have influenced Virgil’s decision to place the relationship between Rome and Carthage at the heart of the national epic he probably began working on the same year. The Aeneid consists of 9,895 lines of hexameter verse, divided into 12 books. The first six, modelled on Homer’s Odyssey, describe Aeneas’ journey from Troy to Italy, where he is fated to found a new city, and his descendants later to found Rome itself. The second six, roughly corresponding to Homer’s Iliad, describe the war the Trojans had to fight to establish themselves in Latium. P. VERGILIĪ MARŌNIS AENĒIDOS, LIBER I Arma virumque canō, Trōiae quī prīmus ab ōrīs Arms man-also sing-I Troy’s who first from shores Ītaliam, fātō Italy profugus, Lāvīniaque vēnit by-fate refugee Lavinian-also came-he lītora, multum ille et terrīs iactātus et altō coasts much he both on-land troubled and at-sea vī superum saevae memorem Iūnōnis ob īram; by-force of-gods of-cruel memorable Juno’s because-of anger multa quoque et bellō passus, dum conderet urbem, much also and in-war suffered until found-could-he city īnferretque deōs Latiō, genus unde Latīnum, carry-could-he-also gods to-Latium race from-whom Latin Albānīque patrēs, atque altae moenia Rōmae. Alban-also fathers and high walls Rome’s Virgil begins by setting out his theme and particularly the hostility to Aeneas and the Trojans of Juno, queen of the gods and patroness of Carthage, the city which will become Rome’s most dangerous enemy. The narrative then starts with Aeneas’s fleet leaving Sicily to sail to Italy but caught in a storm arranged by Juno and swept to the coast of North Africa where they are kindly received by Queen Dido, in newly-founded Carthage. Books 2 and 3 present earlier events as told by Aeneas himself to Dido. Aeneas describes how Sinon, pretending to be a fugitive from his own Greek people, tricked the Trojans into bringing the Wooden Horse within their city. The priest Laocoon suspected the Horse was a trick but, after he struck it with his spear, great serpents appeared from the sea and killed both him and his sons, convincing the Trojans that it was the gods’ will that they accept the horse. After the Greeks emerged from the Horse and began to kill and burn, Aeneas tried to resist them but finally obeyed the warnings of the ghost of Hector and of his own mother, the goddess Venus, to flee, taking with him the sacred images that embodied the city. He escaped with his father and son but his wife was lost in the chaos.