High Fantasy

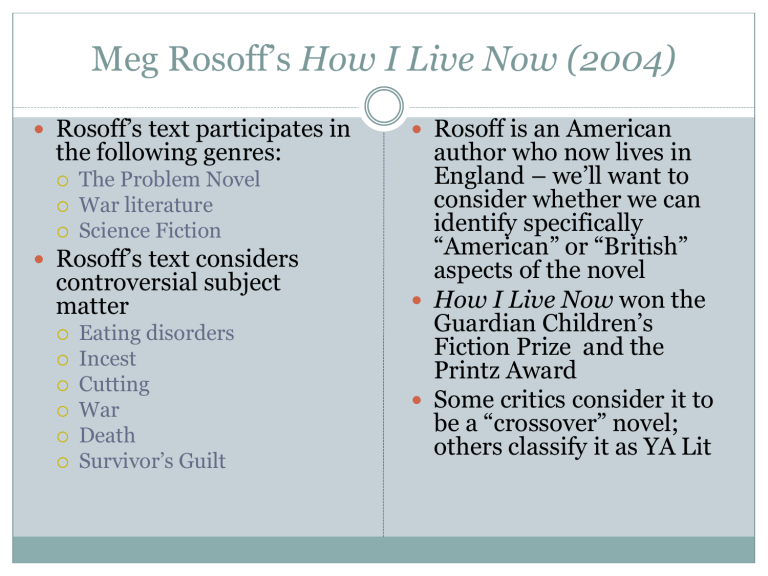

Meg Rosoff’s How I Live Now (2004)

Rosoff’s text participates in the following genres:

The Problem Novel

War literature

Science Fiction

Rosoff’s text considers controversial subject matter

Eating disorders

Incest

Cutting

War

Death

Survivor’s Guilt

Rosoff is an American author who now lives in

England – we’ll want to consider whether we can identify specifically

“American” or “British” aspects of the novel

How I Live Now won the

Guardian Children’s

Fiction Prize and the

Printz Award

Some critics consider it to be a “crossover” novel; others classify it as YA Lit

Reviews

Publishers Weekly:

Teens may feel that they have experienced a war themselves as they vicariously witness Daisy's worst nightmares. Like the heroine, readers will emerge from the rubble much shaken, a little wiser and with perhaps a greater sense of humanity.

The School Library Journal:

Though the novel has disturbing elements, Rosoff handles the harshness of war and the taboo of incest with honest introspection. This Printz award winner is a good choice for book discussions as it considers the disruption of war both physically and emotionally and should be on every high school and public library shelf.

Reviews

Critic John McLay:

Rosoff's writing style is both brilliant and frustrating. Her descriptions are wonderful, as is her ability to portray the emotions of her characters. However, her long sentences and total lack of punctuation for dialogue can be exhausting. Her narrative is deeply engaging and yet a bit unbelievable. The end of the book is dramatic, but too sudden. The book has a raw, unfinished feel about it, yet that somehow adds to the experience of reading it.

Why did the Problem Novel Become Popular in the 1960s?

Critic Gail Murray suggests:

[A] new construction of childhood emerged during the

1960s…. It recognized that children could not always be protected from the dangers and sorrows of real life; they might be better prepared to cope with pain if adults did not try to protect them from it.… The boundaries that had protected children and adolescents from adult responsibilities throughout the 19th century and the first half of the 20th century became much more permeable.… Such previously defined adult issues as sexuality and suffering entered the realm of childhood.

Sheila Egoff’s Definition of The Problem Novel

The protagonist is alienated and hostile toward adults.

Some relief from unhappiness comes from a relationship with an adult outside the family.

The story is often told in the first person and is often confessional and self-centered.

The narrative is told from the point of view of an ordinary child, often in the vernacular; vocabulary is limited; tone is often flat, and emotionally detached.

Dialogue predominates.

The settings are urban.

Sexuality is openly and frequently discussed.

Parents are absent, either physically or emotionally.

Children’s Literature and War

On May 1st 2004, at Froebel College, Roehampton, in partnership with NCRCL*, Action for Children’s

Arts ran an Inspiration Day entitled Children’s

Literature and War.

The main speakers were the Children’s Laureate

Michael Morpurgo, Elizabeth Laird, Michael

Foreman, Charles Way - all prize winning writers who have written fictional stories set against a background of war; academic Geoff Fox; and special guest Philip Pullman.

*National Center for Research in Children’s Literature

Conclusions of the NCRCL Participants

Children deserve psychological depth in the depiction of war they need to see and understand the enemy as human.

Fiction acts as a bridge between the fantasy of warfare (as for example in the filmed battle scenes of the Lord of the Rings) and the brutal reality of news coverage seen almost daily by children on the television.

The imagination has a transfiguring effect and some hope can be presented even within the bleakest and most poignant of stories.

Particularly challenging is the task of representing current conflicts rather than past conflicts - even those of the more recent past (World War

2) which, although vivid to most of the writers represented in these discussions, nevertheless remain distant to the present generation of children.

As artists, the clearest responsibility that they saw was to present a personal vision of the truth.

Science Fiction: Sub-genre of Fantasy

Science Fiction is a sub-genre of Fantasy, so let’s begin by defining the genre:

A work of fantasy is one in which at least one element of the story does not conform to natural laws.

When discussing fantasy, we distinguish between the primary world and the secondary world. The primary world refers to the world we live in, where natural laws are observed. The secondary world refers to another place, where one or more of the natural laws have been suspended.

Science Fiction: Primary v. Secondary World

In some works of fantasy, characters only know a primary world, but it is a world in which something happens that does not conform to natural laws. For instance, the Harry Potter series takes place in the primary world, as witches and wizards live alongside

Muggles in modern day Britain. Sometimes they are able to shroud their actions from Muggles by hiding

Hogwarts in a mist or placing the Ministry of Magic underground in London – however, there is not a separate magic world.

Science Fiction: Primary v. Secondary World

In other works of fantasy, characters begin in the primary world, but find some way to enter the secondary world. In the C.S. Lewis Narnia series, for instance, the characters find a portal to a secondary world through a disused wardrobe.

Finally, there are fantasy texts in which the characters live in a secondary world throughout the novel. A good example of this sort of text would be

Lois Lowry’s The Giver, which takes place in an entirely fictional society.

Types of Fantasy

Most scholars agree that there are four subgenres of

Fantasy:

animal fantasy time fantasy

high fantasy science-fiction fantasy

Animal Fantasy

Judith Hillman notes: Animal fantasies derive from one of the oldest forms of literature – the beast fable.

“Fables, folktales, and other forms of traditional literature showed human affinity to animals in the many depictions of anthropomorphism.” In modern fantasy, “the best examples of children’s literature show a careful blend of human characteristics with animal qualities.”

Time Fantasy

Judith Hillman’s definition: “The notion that time runs in several directions has long fascinated authors, scientists, and philosophers. Is time cyclical or is it linear? Do other worlds exist in different time schemes? In time fantasies, authors construct parallel worlds that touch our primary world in places, allowing time travel back and forth. Another world running simultaneously to our presents all sorts of possibilities in literary invention. In addition, there are historical time fantasies in which a character from the present can go back in time, or a character from long ago can come to the present.”

High Fantasy, Part I

High Fantasy: High fantasy evolved from an earlier form of literature, the medieval romance of the 11 th and

12 th centuries. In this form, the exploits of hero figures such as King Arthur and his knights were featured, and the plots centered on a quest that would prove the worthiness – or lack thereof – of the central characters.

In recent years, a number of novels have been set during this time period, but the medieval world has gone from being a primary world setting to a secondary world setting – its emphasis on the exploits of heroic, its focus on the code of chivalry, and its setting all mark its difference from the modern world.

High Fantasy, Part 2

In High Fantasy, the battle between good and evil is fought on a physical level, but also on a philosophical one – as Hillman notes, “the main character is often a common person who is called on to perform beyond his or her capabilities, but somehow summons the strength to do it.”

Science Fiction Fantasy

In s-ff, the secondary world is typically set in the future or in an unspecified “now.”

The best science fiction balances technological concerns, a solid storyline, and a compelling vision of the future. If it is successful, it leads us to rethink our current society, its values, and its very construction.

Pre-reading Questions

As you read Rosoff’s How I Live Now, you should consider these questions:

Why might Rosoff want to juxtapose a problem novel with a war novel? What insights might young readers take away by comparing their own life issues with broader world issues?

Is there a normative center in this novel? If you feel that there is, identify it and explain WHY you feel it to be a place where ideal human interaction occurs.

In what ways does Daisy grow throughout the narrative? What do you find to be her strengths? Her weaknesses?

Pre-reading Questions

More questions:

Betcha didn’t know that it’s legal to marry your 1 st cousin in

Michigan! It’s also legal in England. But it’s a controversial scenario, as even Daisy recognizes. What did you make of this aspect of the novel? Do you agree with The School Library

Journal reviewer, who comments: “Rosoff handles the…taboo of incest with honest introspection”?

Some critics have argued that Rosoff makes the unreal seem real and the real seem unreal. In other words, she creates a situation in which everyday life becomes strange and unfamiliar, and where strange things become normal. As you read through the text, select at least one or two instances where you think that this happens.

Pre-reading Questions

Still more questions:

The massacre scene is extremely powerful, as is the murder scene earlier in the text. Consider how these scenes are presented – what techniques does Rosoff use to engage her readers with what is incredibly disturbing material?

Read the final section of the novel very carefully. What do you make of the description of the garden? Do you find any symbolism in the description?

Finally, for extra credit, can you identify any places in the text where Rosoff is creating intertextuality with earlier classics of children’s literature?