PowerPoint Presentation - Abstraction in the Art and Architecture of

advertisement

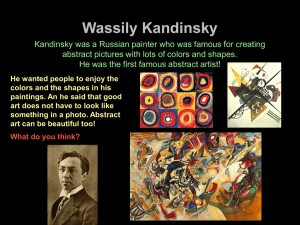

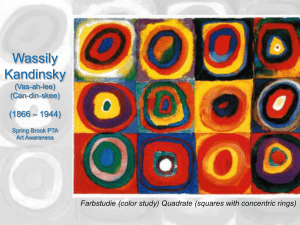

Abstraction in the Art and Architecture of Early 20th-century Russia Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944) The figure of Wassily Kandinsky is seminal in the history of early 20th-century painting. Kandinsky studied law from 1886-92 and then served on the law faculty of the University of Moscow from 1892 to 1896. However, he was increasingly drawn to painting. In 1896, he left Russia and went to Munich in order to study painting there. He painted in a broad and eclectic stylistic range from 1896 until 1909, a range that reflected the changes in European painting in general in the mid to late 19th century. Beach Cabins in Holland, 1902 This painting reveals Kandinsky's understanding of the postimpressionist painters who, after the dissolution of subject matter by light in the impressionist period, sought to re-introduce structure. Here, structure is found not only in the composition of the work, i.e. the arrangement of forms, but in the use of color and the reality of the paint and even the brushstrokes. Historically, from the Renaissance through the late 19thcentury, western art had conceived of the canvas or painted surface as a window or imaginary plane through which another world, usually an ideal world, could be viewed. The ability to arrange that ideal world mathematically through one-, two-, and three-point perspective from the 15th century on reinforced the concept of illusion that underlay the imaginary window. Although the quality of the paint itself on the surface of the canvas had fascinated the baroque painters of the 17th century because of its sensuous nature, the post-impressionists began to treat the painted surface and the paint on the surface as a reality of equal or even greater value than the subject matter represented. The post-impressionist characteristics of Beach Cabins in Holland also permeate Bavarian Mountains. The structure of this painting is dependent in large part on the geometry of the forms as they are arranged across the picture plane. Color likewise is used to emphasize the composition while the brushstrokes further articulate the paint as the surface of the work. There is a tension between the flat, two-dimensonal qualities and the illusionistic three-dimensional qualities that enlivens the work. Bavarian Mountains, 1909 Beginning in 1909, Kandinsky began to work on three series of paintings which he named "improvisations," "compositions," and "impressions,." Each series had a specific definition. • Impressions: paintings which retain an impression of exterior nature • Improvisations: paintings which arise from an inner emotion • Compositions: paintings built up from preliminary studies and into whose construction the painter's consciousness enters Improvisation 9, 1910 In this work, the illusionistic qualities begin to subside, somewhat subordinated by the almost vibrating quality of the brushstrokes and the rich harmony of the color palette. Line-whether as outline, as separator between forms, or as an active agent of movement-becomes an important expressive vehicle along with color and shape. Composition 2, 1910 The considerable number of figural components in the composition along with the very active sense of movement is amplified by the sense of rapid brushstrokes, the lack of an organizing "gravity" or spatial orientation, and by the strong color constrasts. The complex nature of the painting suggests that it fulfills the definition of the "composition" as a painting "built up from preliminary studies." However, the rest of the definition says, "...into whose construction the painter's consciousness enters." This suggests that the painting is very directly expressive of the mind, soul or spirit of the painter; and that somehow an element of the consciousness of the painter is the real subject of the work, not the recognizable forms that the viewer can observe. The expressive value of the elements that make up the painting seem now to dominate Kandinsky's notions about what the activity of painting means. Of course, Kandinsky was not just a theorist. His writings were widely read and may have reached more people than his paintings, but he was nevertheless a painter of significance. In 1910, before he published Concerning the Spiritual in Art, Kandinsky took the decisive step in the direction he had been moving by painting the first work that totally eliminated recognizable subject matter and relied on abstract form and the "vibrating" power of color to construct its composition. As with most theory, Kandinsky's writing is an effort to explain what he achieved in his work, not a formula for making the work happen. In assessing his own motivations and passions, he came up with the critical apparatus by means of which he could evaluate even his own work, let alone offer a critique of the art around him. First Abstract Water Color, 1910 Autumn, 1914 In 1914, Kandinsky returned to Moscow, where he remained until 1921. In 1918, after the October Revolution, he became a member of the Fine Arts Division of the Commissariat for Public Instruction and Professor in the Government Art Workshops. He left Russia and returned to Germany in 1921 where, in 1922, he became a member of the faculty at the Bauhaus in Weimar. Not only did Kandinsky pursue painting in his studio; but he also tried to formulate his ideas in writing. During 1912, his two principal texts appeared in the form of a book (Concerning the Spiritual in Art) and an article ("On the Question of Form"). In these, he laid the theoretical groundwork for a purely abstract art, an art that is devoid of traditional illusionism and recognizable subject matter. In Concerning the Spiritual in Art, Kandinsky suggests that true art comes of inner necessity and must not only speak to and for its own time but must lead its time into the future. That is beautiful which is produced by internal necessity, which springs from the soul. He posits that just at the beginning of the 20th century humanity is at a turning point in which the effects of 19thcentury materialism will have to be combatted by soul-sensitive artists who recognize the power of the spiritual. The spiritual life to which art belongs, and of which it is one of the mightiest agents, is a complex but definite movement above and beyond, which can be translated into simplicity. This movement is that of cognition. He compares the elements of painting to the elements of music, defining some compositions as "melodic" and others as "symphonic," and to the elements of poetry. He further points to French painting--especially Matisse for color and Picasso for form--as the "great signposts pointing toward a great end." Kazimir Malevich (1878-1935) Russian artists in the early 20th century were well aware of western European developments through periodicals, travels to France, italy, Germany, and Holland and by contact with the works produced in western Europe that were owned by private Russian collectors. Although Russian music and ballet were highly developed in the 19th century and had a strong theoretical base as well as a good tradition and reputation, the visual arts remained more derivative. Twentieth-century artists saw the need to participate in the revolutionary experiments of the cubists and other western European groups. Kazimir Malevich studied art in Moscow and visited the private collections of important collectors. By 1911, he had experimented with painting in the cubist mode. For two years, he explored cubism and futurism (the radical movement led by Marinetti in Italy). Cow and Violin, 1913 Cow and Violin of 1913 reflects Malevich's interest in cubism as well as his appreciation of the power of folk art. It was common among many late 19th-century and early 20thcentury artists, such as Picasso, to seek new energies within old and so-called primitive art. Here, Malevich draws on the compositional and formal strategies of cubism while retaining the subject matter of folk art. Bather, 1911 In this work, Malevich explores the possibilities of giving the painting structure by virtue of its color, line, and brushstroke, stressing the flatness of the canvas and the primacy of the act of placing the paint on the canvas. This painting still derives from western influences but begins to explore aspects of western styles that lead to more important achievements in Malevich's work. Nevertheless, Malevich was plagued by the persistence of subject matter in these works, even if the subject matter was only residual. He finally took the decisive step in 1913 by completing eliminating recognizable subject matter. He drew a black square on a white field, a pencil work and the first example of the style that he suprematism.