The History of Humor

By Don L. F. Nilsen

and Alleen Pace Nilsen

42

1

Two Visual Anachronisms

42

2

42

3

The History of Comedy

• “Greek comedies were often bawdy or

ribald and ended happily for everyone.”

• “To Chaucer, Shakespeare, and other

writers of the Middle Ages and

Renaissance, a comedy was a story

(but especially a play) with a happy

ending, whether humorous or not.

• (Triezenberg [2008]: 525)

42

4

Homer (9th-8th Century BC)

• “Aristotle’s Poetics, includes Homer in his

discussion of the comic:”

• “A poem of the satirical kind cannot indeed

be put down to any author earlier than

Homer; though many such writers probably

there were.”

• “But from Homer onward, instances can be

cited—his own Margites, for example.”

• Triezenberg [2008]: 525)

42

5

Old Comedy, Middle Comedy and New Comedy

• Old Comedy of the 6th & 5th Centuries BC often made

fun of a specific person and of current political

issues.

• Middle Comedy of the 5th & 4th Centuries BC made

fun of more general themes such as literature,

professions, and society.

• New Comedy of the 4th & 3rd Centuries BC usually

revolved around “the bawdy adventures of a

blustering soldier, a young man in love with an

unsuitable woman, or a father figure who cannot

follow his own advice.”

(Triezenberg [2008]:

525)

42

6

Aristophanes (c450-c388 BC)

• “Of the Old and Middle comedies, the only ones that have

survived complete are eleven plays of Aristophanes.”

• “The Clouds lampoons Socrates in heaven, in the Old tradition,

while Lysistrata makes fun of human nature in general.”

• In Plutus both the wealth and the poverty in Athens are

personified. The citizenry are so distracted that they neglect

the gods.

• Plutus is considered to be Middle comedy.

• (Triezenberg [2008]: 525)

42

7

Titus Maccius Plautus (c254-184 BC)

Plubius Terentius Terence (185-c159 BC)

• “Comedy in the Roman Empire is generally

reduced to the works of Plautus and Terence,

the former of whom lived at about the same

time as Menander, the latter about a century

later.”

• Both Plautus and Terence wrote plays of the

old Greek sort—“farces involving the same

stock characters (father, soldier, slave) and

which, unlike the plays of Aristophanes,

offended no on in particular.”

• (Triezenberg [2008]: 526)

42

8

Menander (fl. 160-135 BC)

• “The author of New comedy whose work has

best survived the ages is Menander.”

• Menander’s Dyskolos (The Grouch) was

discovered in 1957.

• “Many other long pieces of Menander’s work

have survived in Latin translations by

Terence and Plautus.”

• (Triezenberg [2008]: 525)

42

9

Dante Alighieri (1265-1321)

• Most of Dante’s “The Divine Comedy” is not at all funny.

• It is about “Paradiso” as contrasted with “Purgatorio” and the

“Inferno.”

• It was called a comedy because it is “a story about the

powerless vs. the powerful, or the little man vs. the big man, or

even about the perils and pitfalls of social pretence.”

• And thus, “The Divine Comedy” was indeed a “comedy” only in

the classical sense of the word.

(Triezenberg [2008]: 525)

42

10

• “The Inferno, the first installment of

Dante’s The Divine Comedy, describes

damned souls engaging in bawdy

behavior and word play.”

• The second and third installments of

The Divine Comedy are however

distinctly not funny, and demonstrate

that in the fourteenth century “a

comedy need do nothing more than end

happily”

(Triezenberg [2008]: 526).

42

11

Giovanni Boccaccio (1313-1375)

• Boccaccio’s Decameron is “a collection of

stories told by a group of ten nobles who

have fled the Black Death by shutting

themselves up in a lonely castle.”

• Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales were influenced

by Boccaccio’s Decameron, and they have

basically the same structure.

• (Triezenberg [2008]: 526)

42

12

Geoffrey Chaucer (c1342-1400)

• “In the Middle Ages, the farces, bawdies, and

satires of Greek and Roman literature

continued to be popular.”

• “Chaucer is best known for his Canterbury

Tales, some of which (e.g. The Miller’s Tale)

are both bawdy and still funny by today’s

standards.”

• (Triezenberg [2008]: 526)

42

13

• “Chaucer also penned The Romaunt of

the Rose, a satire on love and courtship,

and The House of Fame which seems to

spoof Dante’s idea of the narrator and

the guide.”

• “In Chaucer’s version, the narrator

would rather not listen to the guide.”

• (Triezenberg [2008]: 526)

42

14

Erasmus (1466-1536)

• “Erasmus has very clear political and

religious objectives in The Praise of Folly,

where Folly is nursed and instructed by Self

Love, Flattery, Intemperance, and a number

of other personified sins, and goes on to

criticize the Catholic Church.”

• “Oddly enough, the joke was on Erasmus,

who was a staunch Catholic, but whose work

became a major catalyst of the Protestant

Reformation.”

(Triezenberg [2008]: 527)

42

15

François Rabelais (c1483-1553)

• Rabelais published a series of five books

collectively known as Gargantua and

Pantagruel.

• “Gargantua and his son Pantagruel are two

giants of unfixed size, who can sometimes fit

into a normal building and sometimes hold

whole civilizations inside of their mouths.”

• Triezenberg [2008]: 526)

42

16

“These books contain satires on the

Roman Catholic church, bawdy stories,

and scatological humor as well as plain

silliness that reminds the modern reader

of Monty Python’s Flying Circus.

• “Rabelais’ brand of silliness and

freedom from the laws of physics and of

logic was discussed by the critic

Bakhtin, who calls this atmosphere the

‘carnival’ world.”

(Triezenberg [2008]: 526)

42

17

William Shakespeare (1564-1616)

• “Shakespeare’s plays are sometimes divided into

Comedy, Tragedy, and History.”

• “The history plays are, obviously, those based on

historical personages such as Richard III and Henry

IV.”

• “The difference between comedy and tragedy is still

very much the same as in Greek plays—comedies

have happy endings and tragedies have sad ones;

tragic heroes are larger than life, while comic heroes

are flawed.”

• (Triezenberg [2008]: 527)

42

18

• “Shakespeare’s comedies are also usually

funny, but unlike the Greek bawdy plays and

satires, their humor lies in word play—puns,

allusions, and double-entendres that are very

often lost on today’s audience.”

• “Careful perusal of an annotated version of

Love’s Labours Lost or All’s Well That Ends

Well will reveal the surprising density of jokes

in these plays, which are supposed to have

had Elizabethan audiences roaring with

laughter”

(Triezenberg [2008]: 527).

42

19

• Falstaff, a great comic and humorous

character demonstrates Bakhtin’s “carnival.”

• Falstaff appears not in comedy plays, but in

history plays--Henry IV parts I and II.

• Shakespeare’s tragedies, too, often include a

figure of a clown or fool. His job is not so

much to provide mirth or laughter as it is to

provide commentary that is sometimes satiric

and very often funny.

• (Triezenberg [2008]: 527)

42

20

Court Jesters: From the Middle Ages to the Renaissance

During the Middle Ages the kings

had court jesters.

The jester’s septer was a

ludicrous representation of the

king’s septer, which represented

power.

Because They were not supposed

to be in competition with the king,

they tended to be deformed

In Shakespeare’s plays, the

midgets with humped backs and

king’s fool represents these

bug eyes.

midieval traditions.

And they were not very smart.

But in King Lear the fool is

smarter than the king.

They also wore cap and bells and

motley clothes, and funny shoes.

And they carried the “jester’s

septer” containing an image of

the jester’s face.

42

And often smart fools, because

they were so “marked” could say

things to the king that noone else

was allowed to say.

21

Fools during the Renaissance, and beyond

There are many foolish fools in

Shakespeare’s plays.

And out of these Renaissance

traditions came the street jugglers

and street musicians,

There are also many wise fools in

Shakespeare’s plays.

And the Punch and Judy shows,

Not only is there the wise fool in

King Lear, but there is also the

dead fool named Yorrick in Hamlet,

and the wise foolish women in The

Taming of the Shrew, and Much

Ado about Nothing.

And Italy’s Commedia d’el Arte

And France’s Comedie Française,

And England’s “Comedy of

Humours,” and “Comedy of

Manners.”

And America’s ventriloquists and

editorial cartoonists.

42

22

The Eighteenth Century

• “The eighteenth century saw the rise of

a new kind of humorous author: the

wit.”

• “A wit is usually a person who can

make quick, wry comments in the

course of conversation.”

• (Triezenberg [2008]: 528)

42

23

Jonathan Swift (1667-1745)

• Swift is best known for his novel Gulliver’s Travels

“in which sailor Lemuel Gulliver recounts his visits

to strange lands inhabited by fantastic peoples.”

• “Gulliver’s last voyage finds him in a land where

horses are the dominant species, and keep dumb,

barbaric humans (called Yahoos) as beasts of

burden.”

• This novel is a humorous reflection on the failings of

civilization.

(Triezenberg [2008]: 528)

42

24

• Swift’s A Modest Proposal is an essay

which suggests that the problems of

overpopulation and starvation in the

lower classes (especially in Ireland) would

be readily solved if they would eat their

own children.”

• (Triezenberg [2008]): 528)

42

25

William Congreve (1670-1729)

• William Congreve was a contemporary of

Jonathan Swift and Alexander Pope.

• His The Old Batchelor (1693), The Double

Dealer (1693), Love for Love (1695), and The

Way of the World (1700) are all satires filled

with ironies and paradoxes.

• (Triezenberg [2008]: 528)

42

26

Alexander Pope (1688-1744)

• While Jonathan Swift was writing satirical novels,

Alexander Pope was writing satirical poetry.

• Pope’s “Imitations of Horace satirizes the policies of

George II and Horace Walpole while imitating the

form of a classical poet.”

• Pope’s Moral Essays are works more of ridicule

than of satire, and are not considered humorous by

everybody.

• Pope’s most celebrated satire was named Dunciad.

• (Triezenberg [2008]: 528)

42

27

Voltaire (François-Marie Arout (16941778)

• Voltaire dabbled in many different

literary forms—“from novels to plays,

history, poetry, letters, and essays.”

• “His signature wit is present in all, and

some are expressly meant to be satires,

especially on the Catholic church,

censorship, and French civil liberties

(or lack of)” (Triezenberg [2008]: 528).

42

28

Henry Fielding (1707-1754)

• Tom Jones is a light-hearted tale of

adventure, containing many hilarious

episodes and ends happily for

everyone who deserves to so end.”

• (Triezenberg [2008]: 528)

42

29

Charlotte Lenox (1720-1804)

• Charlotte Lenox’s The Female Quixote

“tells the story of Arabella, a young

woman whose only education and

contact with the outside world has

consisted of reading romance novels,

and the adventures she has when she

becomes independently wealthy and

comes face to face with the outside

world.” (Triezenberg [2008]: 528)

42

30

Jane Austen (1775-1859)

• Jane Austen’s characters are

“simultaneously true-to-life and

ridiculous.”

• “All of her novels can simultaneously

be read as scorching satires of human

nature and society manners.”

• (Triezenberg [2008]: 529)

42

31

Nikolay Vasilyevich Gogol (1809-1852)

• Some of Gogol’s short stories like The

Nose are “bizarre, almost to the point

where humor is lost to wonder and

confusion.”

• In The Nose “a man’s nose goes AWOL

and walks about the city causing

trouble.”

42

32

• But some of Gogol’s short stories are

“so dark and horrible that, while the

story is most certainly a joke with a

punch line, the reader is loathe to

laugh.”

• For example, in The Overcoat “a poor

clerk starves himself to buy a new coat,

which is stolen from him on the first

night he wears it.”

• (Triezenberg [2008]: 529)

42

33

William Makepeace Thackeray (1811-1863)

• Both Charles Dickens and William

Makepeace Thackeray “became enormously

popular for sympathetic portrayals of

eccentric characters.”

• There are many straightforward jokes and

much satire in their novels, which can be

considered comedies because they end well

for almost everyone.

• (Triezenberg [2008]: 529)

42

34

Charles Dickens (1812-1870)

• Charles Dickens is famous for the eccentrics

that he portrays in his novels.

• For example, “the characterizations of Silas

Wegg and Mr. Venus in Our Mutual Friend

“make us laugh in delight at the recognition

and exaggeration of a ‘type’ of person that

we ourselves have met in real life.”

• (Triezenberg [2008]: 529)

42

35

Mid 19th Century

• James Russell Lowell’s Birdofreedum Sawin said,

“at any rate, I’m so used up I can’t do no more

fightin’ / The only chance thet’s left to me is politics

or writin’.”

• “On the western frontier, wise fools, con-men, and

tricksters like Johnson J. Hooper’s Simon Suggs

and George Washington Harris’s Sut Lovingood

were employed to portray the rough and

unsophisticated American as an ironic hero. Suggs

was lazy and dishonest, and he knew it was “good to

be shifty in a new country.”

(Mintz in Raskin [2008] 287)

42

36

Sut Lovingood (1814-1869

• Sut Lovingood expressed a rude racism and

sexism.

• He argued in favor of drinking, sex,

roughhousing, and a deep mistrust of

preachers, widows, and other guardians of

civilization.

• His freedom, joy of life, and cynicism

supported the counter culture.

(Mintz in Raskin [2008] 287)

42

37

Mark Twain (1835-1910)

• Like Charles Dickens in England, Mark

Twain in America wrote vernacular

novels with eccentric characters.

• Twain wrote stories about characters

that are “more real than real life, more

true to type than any true person could

be.”

(Triezenberg [2008]: 529)

42

38

Oscar Wilde (1854-1900)

• Oscar Wilde is “a great comic playwright

whose only joke, it seems, was to contrast

the honest, industrious morés of the public

world with the lazy selfish motivations of his

elegant heroes”

• “Wilde’s plays exhibit a gift for word play

and repartée, as well as cultivation of

ridiculous situations.” (Triezenberg [2008]:

529)

42

39

P. G. Wodehouse (1881-1975)

• Wodehouse wrote many novels about

the nitwit Bertie Wooster and his

gentleman’s gentleman, Jeeves.

• “Wodehouse’s works usually hinge

around a ridiculous social situations

created by the characters themselves.”

• (Triezenberg [2008]: 530)

42

40

E. B. White (1899-1985)

• In 1941, E. B. White wrote, “Humor can

be dissected as a frog can, but the

thing dies in the process and the

innards are discouraging to any but the

pure scientific mind.”

• (Triezenberg [2008]: 530)

42

41

George Orwell (1903-1950)

• Orwell’s Animal Farm is an allegory.

• On the surface it is a story about

personified farm animals.

• But it is probably also about the

Russian revolution. (Triezenberg

[2008]: 535)

42

42

Isaac Asimov (1920-1992)

• Isaac Asimov is famous as a science

fiction writer, but he also published two

books of jokes, one in 1971, and one in

1993.

• These joke books contain commentary

on why the jokes are funny, and

suggestions on how to become a good

joke teller. (Triezenberg [2008]: 530)

42

43

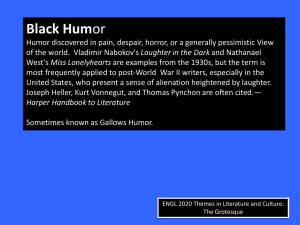

Joseph Heller (1923-)

• Joseph Heller wrote gallows humor in which he tried

to make people laugh and then feel like fools for

having laughed.

• He wrote Catch 22 in which Yosarian had to prove

that he was insane in order to get out of the army,

but by trying to get out of the army he was proving

that he was sane.

• Another “catch 22” in the novel was that they had to

fly a certain number of missions before returning

home, but the number kept increasing.

42

44

Television Humor

• Television opened huge new vistas for

performing arts in general, and humor in

particular.

• Early TV featured humorous variety shows

like Laugh In, and Saturday Night Live.

• There was also much sketch humor in such

shows as Monty Python’s Flying Circus.

• (Triezenberg [2008]: 530)

42

45

The First Comic Strips

• “The early strips such as ‘The Yellow Kid’ were

curious combinations of down-to-earth slapstick,

topical joking, and rather abstract referencing.”

• “In the hands of a Windsor McCay (‘Little Nemo in

Slumberland,’ ‘The Adventures of the Rare-bit

Fiend,’) they were creative indeed, and could border

on the surreal and handle social satire at the same

time.”

• George Herriman’s “Krazy Kat’ mostly “settled for a

domestic humor involving marital conflict and bratty

kids.”

(Mintz in Raskin [2008] 288)

42

46

The Golden Age of Humor

• “The golden age of humor” was often

considered to be the 1920s but would be

more accurately placed from the end of WWI

to the early 30s.

• During this golden age, we see the

development of the “little man” in Casper

Milquetoast, Andy Gump, Jiggs, Mutt (of

“Mutt and Jeff”), and Dagwood (of “Blondie

and Dagwood”).

(Mintz in Raskin [2008] 288)

42

47

Blondie and Dagwood

• “Dagwood loses battles to the illogic of his

wife, Blondie, his kids, the dog, his boss, and

the neighborhood bridge club (intruding on

his bath). His defense is napping as often as

he can, eating everything in sight [“Dagwood

Sandwiches”], and knocking down the

mailman as he rushes off to work in the

morning.”

• “It was a comic counter-balance to American

arrogance, self-confidence, and unrealistic

self-understanding.”

• (Mintz in Raskin [2008] 288-289)

42

48

The 1940s

• The humorous comic strips that were revived

after the Second World War included Walt

Kelly’s “Pogo,” and Al Capp’s “Li’l Abner.”

• “Kelly’s swamp fables were allegorical

‘swamps’ themselves, loaded with social

and political commentary lurking behind the

antics and interactions of the familiar cast of

animal characters.”

• Al Capp’s “hillbillies” gave access to Capp’s

views on topical events, government, and

American values.

(Mintz in Raskin [2008] 289)

42

49

Charles Schulz’s Eccentrics

•

The “Peanuts” comic strip uses kids to reflect adult neuroses:

•

“Lucy uses her meanness to compensate for the unrequited love she

has for Schroeder (who keeps trying to play Beethoven on a toy piano

with painted on black keys).”

•

“Linus has his blanket to comfort him when his childhood fears and

fantasy get in the way of his intellect,”

•

“and the dog, Snoopy, deals with the limitations of his ‘dogness’ by

pretending to be the Red Baron, or a lawyer, writer, hockey player,

detective and resident of a deluxe doghouse complete with a pool

table and rare paintings.”

•

“Charlie Brown, the consummate loser, little man character, reflects all

the fears, weaknesses, and failures of modern man. He knows that

Lucy will pull the football away from him when he tries to kick it, yet

every year he tries again.” (Mintz in Raskin [2008] 289)

42

50

History of International Humor Conferences

1976: Cardiff Wales

1982: Los Angeles, CA

1984: Tel Aviv, Israel

1985: Cork, Ireland

1982-1987: Tempe, AZ

1988: West Lafayette, IN

1989: Laie, HI

1990: Sheffield, England

1991: St. Catharines, Canada

1992: Paris France

1993: Luxembourg

1994: Ithaca, NY

1995: Birmingham, England

1996: Sydney, Australia

1997: Edmond, OK

1998: Bergen, Norway

1999: Oakland, CA

2000: Osaka, Japan

2001: College Park, MD

2002: Forli, Italy

2003: Chicago, IL

2004: Dijon, France

2005: Youngstown, OH

2006: Copenhagen, Denmark

2007: Newport, RI

2008: Alcala, Spain

2009: Long Beach, CA

2010: Hong Kong

2011: Boston, MA

2012: Krakow, Poland

(Carrell in Raskin [2008] 318)

42

51

History of the

International Society for Humor Studies

History of America:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aLdQ4DUnnw4&feature=fvw

Don L. F. Nilsen, Linguistics & Humor:

http://www.public.asu.edu/~dnilsen

The Fifties:

http://oldfortyfives.com/TakeMeBackToTheFifties.htm

International Society for Humor Studies

(Martin Lampert, Web Master):

www.humorstudies.org

42

52

Related PowerPoints

• History of English

42

53

References (2000-2012):

Adams, Bruce. The Revolutions in Russia, Twentieth Century Soviet and

Russian History in Anecdotes. New York, NY: Routledge Curzon, 2005.

Boskin, Joseph. Corporal Boskin’s Cold War: A Comical Journey.

Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2011.

Bryant, Chad. “The Language of Resistance: Czech Jokes and JokeTelling under Nazi Occupation, 1943-1945.” Journal of Contemporary

History 41.1 (2006): 133-151.

Carrell, Amy. “Historical Views of Humor” in Raskin (2008) 303-332.

Davies, Christie. “Humour and Protest: Jokes under Communism.”

International Review of Social History 52 (2007): 291-305.

42

54

Dekker, Rudolf. Humour in Dutch Culture of the Golden Age.

Basingstoke, England: Palgrave, 2001.

Eberhart, Cy. Will Rogers: Discovering the Soul of America.

Bangor, ME: Book Locker, 2010.

Ehrenreich, Barbara. Dancing in the Streets: A History of

Collective Joy. New York, NY: Holt, 2006.

Graban, Tarez Samra. “Feminine Irony and the Art of Linguistic

Cooperation in Anne Askew’s Sixteenth-Century

Examinacyons. Rhetorica 25.4 (2007): 385-413.

Holcomb, Chris. “‘A Man in a Painted Garment’: The Social

Function of Jesting in Elizabethan Rhetoric and Courtesy

Manuals.” HUMOR: International Journal of Humor Research

13.4 (2000): 429-456.

42

55

Lewis, Paul. Cracking Up: American Humor in a Time of Conflict. Chicago,

IL: University of Chicago Press, 2006.

Mintz, Lawrence E. “Humor and Popular Culture” in Raskin (2008) 281-302.

Nilsen, Alleen Pace, and Don L. F. Nilsen. Encyclopedia of 20th Century

American Humor. Westport, CT: Greenwood/Oryx, 2000.

Nilsen, Don L. F. Humor Twentieth-Century British Literature. Westport,

CT: Greenwood Press, 2000.

Olson, S. Douglas, ed. Broken Laughter: Select Fragments of Greek

Comedy. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 2007.

Raskin, Victor, ed. Primer of Humor Research. New York, NY: Mouton de

Gruyter, 2008.

Triezenberg, Katrina E. “Humor in Literature” in Raskin [2008]: 523-452.

42

56

![[Lecture 19] studio system 2 for wiki](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/005217793_1-c296c1b3b7b87d52a223478e417a702f-300x300.png)