The period of Rationalism

Rationalism and Its Impact on

Music

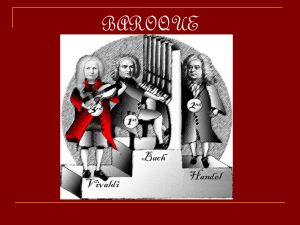

“Baroque”

• Used to identify period in art and music history before

1600 to about 1750

• Originally a pejorative word — overornamented, distorted, grotesque — used by critics from later periods

– does not apply to all arts of that period — e.g., French academic dramatists Pierre Corneille (1606–1684) and Jean

Racine (1639–1699), painter Jan Vermeer (1632–1675)

– certainly does not reflect artists’ ideas in the period

– music includes a variety of styles over long period

Rationalist principles

• Reason supersedes received authority from church or ancients

– Francis Bacon (1561–1626) — clearing away errors in thinking

– René Descartes (1596–1650)

• Discourse on Method (1637) — principles of rationalism

• The Passions of the Soul (1649) — important for aesthetics

• Aesthetic presuppositions

– Humanism — to portray the idea, “imitate” the “sense” of words

• Gioseffe Zarlino, Istitutione armoniche (1558)

• Thomas Morley, A Plaine and Easie Introduction to Practicall

Musicke (1597)

– Rationalism — to move the audience, imitate rhetorical speech

• pathos rather than ethos; affetto rather than virtù

• Vincenzo Galilei, Dialogo della musica antica e della moderna

(1581)

Historical factors in the seventeenth century

• Courts — important for arts

– major powers

• France, absolutism under Bourbons in Paris

• Hapsburg empire — centered in Austria

– principalities in Germany (electors for Holy Roman

Empire) and Italy

– constitutional monarchy in England

• Civil War, 1642

• Commonwealth, 1649

• Stuart Restoration, 1660

• Church — important for the arts

– Roman Catholicism — Jesuitism

– Lutheranism (Orthodox Lutheran and Pietist branches)

– Church of England

Important commercial cities in the seventeenth century

• Venice — port (Adriatic)

• Hamburg — port (North Sea)

• Leipzig — center for publishing

• London — capital and trade center

Monody and basso continuo

Camerata — amateurs in Florence interested in Classical antiquity

• Giovanni de’ Bardi (1543–1612) — host, nobleman, writer

(Discourse on ancient and modern singing, ca. 1578)

• Girolamo Mei (1519–1594) — scholar in Greek literature; lived in Rome, letters to Florence

• Vincenzo Galilei (late 1520s to 1591) — lutenist and singer, theorist (Dialogo della musica antica e della moderna, 1581)

– objection to polyphonic song on principle

– monodic texture based on Mei’s information about Greek drama

– rhetoric as model for moving affections

Monodic texture — homophony

• Vocal part

– declamation influenced by existing formulas for singing strophic poems, Camerata’s theories

– ornamentation (derived from Renaissance improvisation in polyphony)

• Bass treatment

– Renaissance basso seguente — essentially lowest line

– basso continuo from ca. 1590s

• real, independent part as polar opposite of melody, freeing vocal bass

• addition of figures — practical, but optional

• Giulio Caccini (ca. 1545–1618) — singer and composer

– Le nuove musiche (1602) — explained and illustrated new style

Caccini, Le nuove musiche (1601)

Concertato scoring

• New ideal — exploit heterogeneous performers

– from Latin concertare — to contend or fight

– unlike humanist ideal of homogeneous, a cappella sound

• Usages of term

– sixteenth century — colla parte (e.g., Cristoforo Malvezzi,

1589, reports that a madrigal was “concertato” with instruments)

– 1587 — Gabrieli collection — first use in title

• polychoral, voices and instruments

– 1602 — Lodovico Grossi da Viadana, Cento concerti ecclesiastici

• one or more singers with organ basso continuo

– 1610 — Monteverdi, 1615 Giovanni Gabrieli

• voices and instruments, independent, idiomatic roles

Seconda pratica harmony

• Sixteenth-century harmonic style — panconsonance

– theorist — Zarlino, Istitutione harmoniche (1558)

• Mannerism — chromaticism and cross-relations

– e.g., Carlo Gesualdo (ca. 1561–1613)

• Seconda pratica

– new dissonances permitted — including accented passing tones and neighboring tones, appoggiaturas, escape tones

– G. M. Artusi (ca. 1540–1613) — attacked dissonances in new style with score (no text) examples from madrigals by

Monteverdi, 1600

– Claudio Monteverdi (1567–1643) — reply in Foreword prefacing Madrigals, Book 5 (1605), amplified by

Dichiarazione in Scherzi musicale (1607) by his brother Giulio

Cesare Monteverdi (1573 to ca. 1630), justifying unusual harmony as rhetorical expression of text’s affect

Questions for discussion

• How does the change from Humanist to Rationalist aesthetics and musical style compare to the change at the beginning of Humanism?

• How are rational and passionate aspects of musical experience kept in balance or synthesized in seventeenth-century musical thought and style?

• Compare basso continuo texture to earlier textures in

Western music.