Galileo

advertisement

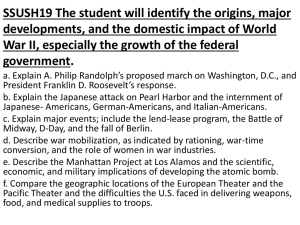

Understanding Theatricalism and Epic Theater 2010.05.20 The stage as platform • Expressionism in Germany as early as 1912 was highly influential in the arts, most especially in writing and performance styles for the theater. • The stage was treated as a platform and was used to comment on the social, economic and political issues of the times. Bertolt Brecht (1898–1956) Georg Kaiser (1878-1945) From Morning to Midnight (1913) The oppressive restrictions of life lead to a banker’s suicide Ernst Toller (1893 - 1939) Epic theory and practice • As evolved by Erwin Piscator and Brecht, epic theory was both a new way of writing for the theater and a different style of performance. • Developed over 40 years, Brecht’s own ideas of “epic theater” were more complex and ambitious than those of Erwin Piscator(1893 -1966 ) was Piscator. German theatre • As a playwright, Brecht thought of dramaadirector and producer who, as episodic and narrative: a sequence of with Bertolt Brecht, was the incidents or events narrated without foremost exponent of epic artificial restrictions as to time, place, or theatre, a form that emphasizes the sociopolitical content of formal plot. drama, rather than its emotional manipulation of the audience or on the production's formal beauty. Galileo Bertolt Brecht The play Galileo by Bertolt Brecht, translated by Charles Laughton and directed by Gary M. English, opened at UConn’s Harriet S. Jorgensen Theatre. Bertolt Brecht • 1898-1956 • A German poet, playwright, and theatre director. An influential theatre practitioner of the 20th century, Brecht made equally significant contributions to dramaturgy and theatrical production, the latter particularly through the seismic impact of the tours undertaken by the Berliner Ensemble—the post-war theatre company operated by Brecht and his wife and long-time collaborator, the actress Helene Weigel—with its internationally acclaimed productions. Critical introduction to Galileo • Brecht’s only play based on a historical figure, the 17th century Italian astronomer and physicist, Galileo Galilei (1564-1642), who challenged prevailing notions of astronomy by suggesting that the earth was not the center of the universe but rather revolved around the sun, was written in three versions over a period of 19 years. • The play embraces such themes as the conflict between dogmatism and scientific evidence, as well as interrogating the values of constancy in the face of oppression. Critical introduction to Galileo • The second version opened at • The first version of the play was the Coronet Theatre in Los written between 1937 and 1939; Angeles on 30 July 1947. This was the second (or 'American') version directed by Joseph Losey and was written between 1945–1947, Brecht, with set-design by Robert in collaboration with Charles Davison. Laughton played Galileo, Laughton. The play received its with Hugo Haas as Barberini first theatrical production at and Frances Heflin as Virginia. This the Zurich Schauspielhaus, production opened at the Maxine opening on 9 September 1943. Elliott's Theatre in New York on 7 This production was directed December of the same year. A third by Leonard Steckel, with setproduction, by the Berliner design by Teo Otto. The cast Ensemble with Ernst Busch in the included Steckel himself (as title role, opened in January 1957 Galileo), Karl Paryla and Wolfgang at the Theater am Langhoff. Schiffbauerdamm and was directed by Erich Engel, with set-design by Caspar Neher. The play was first published in 1940. Critical introduction to Galileo • As a playwright, Brecht used historical material – what he called historification – drawn from other times and places in order to get audiences to reflect on oppressive social and political problems and events of the present time. • As a historical scientific figure, Galileo’s life embraced a two fold responsibility: to thee work to be achieved and then Portrait of Galileo Galilei by Giusto Sustermans to humankind. Epic device • Brecht described his ideal theater as using three key devices: historification, epic and alienation. Brecht’s theory of epic staging included progressive scenes with no act divisions to show the ascending or declining fortunes of the central figure. • The epic devices allow Brecht to express his political, sociological and economic arguments, such as the connections between science and industry, individuals and governments and the ultimate victimization of common humanity by both. • The inner makeup of Brecht’s Galileo is determined by a hedonistic indulgence of life’s pleasures and an excessive joy in scientific experimentation and discovery. 1971 Berliner Ensemble production I am become death, the destroyer of worlds • The 1945-46 version of Galileo only slightly masks the theme of the relationship of scientific research to the most profound moral and social questions illuminated by the explosions on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. J. Robert Oppenheimer. We knew the world would not be the same. A few people laughed, a few people cried, most people were silent. I remembered the line from the Hindu scripture, the Bhagavad-Gita... "Now, I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds." I am become death, the destroyer of worlds • Brecht’s concept of alienation is at work on two principal levels in the play: Galileo himself finds his world of 1600 to be unfamiliar, outdated and in need of explanation • Despite the epic devices, Galileo remained an old-fashions play centered on the central figure’s choices under pressure during which he has campaigned to change the world and has capitulated unheroically when faced with physical pain. Eric Bentley called the play a tragicomedy of “heroic combat followed by unheroic capitulation.”” Dialectical theater • Between 1948-1956, Brecht referred to his theater and plays as “dialectical,” further stressing the collision of conflicting ideas and social forces in his plays. • Galileo is an important document as the last aesthetic testament of Bertolt Brecht as a playwright and director. Dramatizes Galileo’s conflict with the church over his assertion that the earth revolves around the sun • Beatrice Manley as a Party Guest in Galileo by Bertolt Brecht. SFAW. Directed by Herbert Blau, l962. • Beatrice Manley as the Housekeeper in The Life of Galileo by Bertolt Brecht, SFAW. Directed by Herbert Blau, l962. • - Robert Symonds as Galileo and Beatrice Manley as the Housekeeper in The Life of Galileo by Bertolt Brecht, SFAW. Directed by Herbert Blau, l962. • The CRT performance of Bertolt Brecht's "Galileo" at UConn through Dec. 12. • Dudley Knight as Galileo Galileo and Gretchen Goode as his daughter, Virginia Galileo, in the CRT production of Bertolt Brecht’s “Galileo,” playing Dec. 3 – 12 in the Harriet S. Jorgensen Theatre. Synopsis • Galileo is short of money. A prospective student tells Galileo about a novel invention, the telescope ("a queer tube thing"), being sold in Amsterdam. Galileo replicates it, but then sells it to the Venetian Republic as his own creation. • Galileo uses the telescope to substantiate Copernicus' heliocentric model of our solar system, which is highly incompatible with both popular belief and church doctrine, and which he publishes in vernacular Italian, rather than traditional scientific Latin, so that it is accessible by the common people. His daughter's marriage to a well-off young man (with whom she is genuinely in love) fails because of Galileo's reluctance to distance himself from his unorthodox teachings. Synopsis • Galileo is brought to the Vatican for interrogation. Upon being threatened with torture, he recants his teachings. His students are shocked by his surrender in the face of pressure from the church authorities. • Galileo, old and broken, living under house arrest, is visited by one of his former pupils, Andrea. Galileo gives him a book (Two New Sciences) containing all his scientific discoveries, asking him to smuggle it out of Italy for dissemination abroad. Andrea now believes Galileo's actions were heroic and that he just recanted to fool the ecclesiastical authorities. However, Galileo insists his actions had nothing to do with heroism but were merely the result of self-interest. Historical background • The play stays generally faithful to Galileo's science and timeline thereof, but takes significant liberties with his personal life. Galileo did in fact use a telescope, observe the moons of Jupiter, advocate for the heliocentric model, observe sun spots, investigate buoyancy, and write on physics, and did visit the Vatican twice to defend his work, the second time being made to recant his views, and being confined to house arrest thereafter. Historical background • One significant liberty that is taken is the treatment of Galileo's daughter Virginia Gamba (Sister Maria Celeste), who, rather than becoming engaged, was considered unmarriageable by her father and confined to a convent from the age of thirteen (the bulk of the play), and, further, died of dysentery shortly after her father's recantation. However, Galileo was close with Virginia, and they corresponded extensively. Allusions • There are a number of allusions to Galileo's science and to Marxism which are not further elaborated in the play; some of these are glossed below. • The discussion of price versus value was a major point of debate in 19th economics, under the terms "value in use" (value) versus "value in exchange" (price). Within Marxian economics this is discussed under the labor theory of value. • More subtly, Marx is sometimes interpreted as advocating technological determinism (technological progress determines social change), which is reflected in the telescope (a technological change) being the root of the scientific progress and hence social unrest. Allusions • The mention of tides refers to Galileo's theory that the motion of the earth caused the tides, which would give the desired physical proof of the Earth's movement, and which is discussed in his Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems, whose working title was Dialogue on the Tides. In the event this theory was a failure - Kepler's suggestion that the moon's gravity caused the tides instead being correct. • The bent wooded rail in scene 13 and the discussion that the quickest distance between two points need not be a straight line (the path of fastest descent of a rolling ball being a curve, not a straight line (which is the shortest path)) alludes to Galileo's investigation of the brachistochrone (in the context of the quickest descent from a point to a wall), which he incorrectly believed to be given by a quarter circle. Instead, the brachistochrone is a half cycloid, which was only proved much later with the development of calculus. A Portrait of Galileo As Coward • Brecht wrote the play partly because he believed that theatrical works must provoke the audience into thinking critically about the world they lived in. And since the intellectual and working life of the 20th century has been dominated by science, the so-called father of modern science, Galileo, was a perfect figure to be represented on stage. • Brecht first wrote the play in 1938 and originally the final scene was sympathetic to Galileo -- he came across as a cunning scientist who recanted before the authorities in order to promote the long-term interests of science. While in exile in the United States during the war, however, Brecht rewrote the play and the major change concerned the final scene. For the dropping of the atomic bomb developed by allied scientists led Brecht to see in Galileo the first instance in the modern era of a scientist giving in to political authority. • Modern science, in other words, was tainted from the very beginning. Galileo became for Brecht a symbol of the tendency of scientists to collaborate with authority in order to protect its narrow interests rather than to align itself with the best interests of humanity as a whole. A Portrait of Galileo As Coward • Andrea: Galileo’s former student who turned against Galileo when he recanted. He is passing through and visits Galileo who passes him a book he has been secretly writing to take out of the country. • Virginia: Galileo’s daughter, whose live has been ruined by her father’s bad career moves and now looks after him during his house arrest. • Galileo: The aged, nearly blind scientist seems to regret his decision to recant even though he has been able to complete a revolutionary work in physics. In this final speech, he reflects on the value of scientific truth in the lives of ordinary people. Building up a part: Laughton’s Galileo • In America, Laughton worked closely with Bertolt Brecht on a new English version of Brecht's play Galileo. Laughton played the title role at the play's premiere in Los Angeles on 30 July 1947 and later that year in New York. This staging was directed by Joseph Losey. • The processes by which Laughton painstakingly, over many weeks, created his Galileo – and incidentally, edited and translated the play along with Brecht – are detailed in an essay by Brecht, "Building Up A Part: Laughton's Galileo.“ Brecht's essay is a testament to Laughton's greatness as an actor, and is remarkable for the sympathetic and detailed portrait it gives of an actor at work. Revisiting epic theater • The work of Erwin Piscator and Bertolt Brecht changed the course of modern European theater. • Although many of the concepts and practices involved in Brechtian epic theatre had been around for years, even centuries, Brecht unified them, developed the style, and popularized it. Epic theatre incorporates a mode of acting that utilizes what he calls gestus. • The epic form describes both a type of written drama and a methodological approach to the production of plays: "Its qualities of clear description and reporting and its use of choruses and projections as a means of commentary earned it the name 'epic'." Brecht later preferred the term "dialectical theatre. Revisiting epic theater • Brecht’s experiment with epic writing and staging resulted in both episodic and narrative plays, the aims of which were to show social and political contradictions at work in the world. • Writing styles that revolted against the “illusion of the real” in the theater spap a period from the early 1900s to the present. Youtube Links • A documentary on the theatre of Bertold Brecht. – Brecht on Stage - 1/3 – Brecht on Stage - 2/3 – Brecht on Stage - 3/3 • Saggio Vita Di Galileo B.Brecht • The Wilma Theater presents The Life of Galileo • 1-BERTOLT BRECHT GALILEO un film de JOSEP LOSEY • Rehearsal for Theatre Pro Rata's production of "Galileo" by Bertolt Brecht References • Brecht, Bertolt. 1952. Galileo. Trans. Charles Laughton. Ed. Eric Bentley. Works of Bertolt Brecht Ser. New York: Grove Press, 1966. ISBN 0802130593. p. 43–129. • Brecht, Bertolt. 1955. Life of Galileo. In Collected Plays:Five. Trans. John Willett. Ed. John Willett and Ralph Manheim. Bertolt Brecht: Plays, Poetry and Prose Ser. London: Methuen, 1980. ISBN 0413699706. p. 1–105. • Danter, Matej. 2001. "History of changes of Brecht's Galileo". Online: New Mexico State University. (accessed 18 March 2006) • Willett, John. 1959. The Theatre of Bertolt Brecht: A Study from Eight Aspects. London: Methuen. ISBN 041334360X. • British Royal National Theatre's web page about its production of Galileo