Uploaded by

台師大王映晴

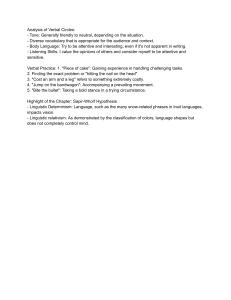

Humor, Interactional Rules, and Grice's Maxims in Language Learning

advertisement

in the ridiculous and destructive situation of having attempted to tell a joke, while afterward having to explain to his learners why and when they should have laughed? ← 214 | 215 → We are all familiar with the benefits of humor in the classroom – the precious moments of complicity; wittiness and fun: the teacher who proposes role-playing games, tells funny stories, and is even self-mocking. Humor in the language classroom gives rise to a host of pedagogical practices, as play and knowledge are intimately linked. Ludic resources can contribute to apprehending and consolidating the content. Languages manifest a great deal of inventiveness and contain a number of strategies in the manipulations of the signifier. The competence of being able to play with language is an indicator of linguistic and cultural competence. Rather than create humor, learners need to identify it, to understand it, and to react to it in an appropriate manner. In order to attain these objectives, teachable segments, in particular scripts proper to the target culture, should be taught (Szirmai, 2012). Humor in the language classroom, this relational emollient, not only serves to loosen up the atmosphere, it makes grammatical commentary as well as the transfer of knowledge more learner-friendly. It also constitutes a subject of study and a means of allowing the learner to perceive culture. It is also a form of detachment with respect to one’s own practice of humor. One must admit that humor in language textbooks all too often simply has an ornamental status. Far from being a simple form of entertainment, however, laughter is essential to understanding ordinary communication in media and literature. Humor challenges standardized visions of the world, which should incite the teacher to show prudence: as what is purely ludic to some may be cynical or offensive to others, in view of their social norms. Humor raises the question of taboos and limits which cannot be transgressed. 5.9 Interactional Rules 5.9.1. Cooperation – Competition Any speaker participating in interaction respects culturally sensitive rules and responds to his interlocutor’s expectations, based on the objectives of the exchange. Grice (1975: 45–46 & 52) demonstrates: our verbal exchanges cannot be reduced to a series of disconnected remarks. Communication is only possible because its protagonists tacitly adhere to a ← 215 | 216 → “cooperative principle” which implies the mastery of a certain number of rules that, echoing Kant, he calls “maxims of conversation”: Quantity, Quality, Relation and Manner. Quantity: 1. Make your contribution as informative as is required. 2. Do not make your contribution more informative than is required. Quality: 1. Do not say what you believe to be false. 2. Do not say that for which you lack adequate evidence. Relation: Be relevant. Manner: 1. Avoid obscurity of expression. 2. Avoid ambiguity. Clearly, in a communication situation (conversation not constituting more than a particular case), maxims can be strategically violated (and this in order to conceal or obtain information). In the following example, instead of strictly conforming to these rules, the communication dynamics rest on voluntary transgression: “A is writing a testimonial about a pupil who is a candidate for a philosophy job, and his letter reads as follows: ‘Dear Sir, Mr. X's command of English is excellent, and his attendance at tutorials has been regular. Yours, etc.’ A does not refuse to play the game, but he does however make light of the rule of quantity in order to imply: X is not competent on a philosophical level (Grice, 1975: 52). The opposition cooperation / competition is, upon first glance seductive in establishing a typology of interactions. Reality is more complicated, however. No interaction exists that cooperates absolutely perfectly while, conversely, in the most polemic interactions possible, there is always room for a minimum of cooperation (Vion, 2000: 126; Maingueneau, 2009: 38–39). The most banal of events allow for observing verbal interaction: “What is said exactly in such and such a situation?”; “What poses problems in foreign language communication?”. Berrier (2001) incites his learners to discover a verbal corpus confronting mini-dialogues leading speakers of different cultural origins to intervene. Conversational analysis provides an interesting line of thought in language teaching and learning theory, likely to result in a deeper reflection concerning the communicative norms that are proper to different societies: the conception of interpersonal relations, the degree of ritualization, or the place of speech and silence, etc. The adaption of linguistic forms and behavior to the communication situation is closely linked to the manner in which, inside the culture in question, objects are named and events are described. The act of naming does, however, constitute a complex relationship between linguistic expression and elements of reality. Every culture categorizes acts and things: indeed, language is turned towards the world in order to capture it. In her terminology, Pavlenko (2011: 199–200) calls 1) “word-to-referent mapping” the ← 216 | 217 → process of linguistic elements and patterns mobilization, through which speakers can refer to the world, and 2) “re-naming the world” the act of naming in a foreign language. Computer-mediated communication, on the other hand, is supposed to conform to a certain number of interactional norms: identification of writers and of recipients, pertinence, clarity, brevity, network technical constraints, use of smileys, etc. Personal communicative profiles aside, is the communicative behavior of Internet users conditioned by their cultural origins? Atifi & Marcoccia (2006) focus on the existence of a cultural variable in digital styles, beyond the behavior assumed to constitute universal netiquette schemas, and submit the hypothesis of appropriation by every culture of a global and standardized model. The comparative analysis of interactions allows for the description of the functioning of the exchanges attested within our societies, and the identification of regularities and cultural (as well as transcultural) variabilities linked to the interactions studied, in more or less formal contexts. Such a procedure necessitates linking the manifestations of one single genre of interaction within several communities. Traverso (2006: 47–55) considers interactive radio programs in Syria and in France: the host welcomes a guest, whom the audience can talk with, by calling in. It is a well established genre in both countries. (Otherwise, globally speaking, the format of the programs is similar.) However, important asymmetries appear in the usages attested by the corpus: 1) appellatives – in French the only category that is used is the pronoun associated with “vouvoiement” (the respectful “vous” form of address, in the plural); in Arabic nine appellative categories are attested; 2) ritual interpolated clauses and wishes – in Arabic the interaction procedure is regularly interrupted by exchanges such as “May God protect your daughter”; in the French corpus there does not seem to be any exchange of this type. Another example is to be found in commercial interaction. The transactional exchange takes place in a business, and the participants assume complementary roles as client and vendor. Windmüller (2011: 113–134) proposes drawing a parallel between two dialogues, taking place in French and German pharmacies, respectively. The interactions are partially ritualized, and not only the opening and closing salutations: giving a prescription, explanations on the taking the medication, advice, in certain countries the pharmacist asks if he should write down the information on the boxes. In language pedagogy, such an analysis constitutes “disruption in daily life”: i.e., social action proper to a pharmacy is part of ordinary daily events that ← 217 | 218 → repeat themselves regularly without having to be challenged at any given moment; it becomes interesting only if the teacher confronts this action with a similar situation in a different cultural environment. 5.9.2 Speech Acts – Social Usages To Hymes (1972a: 56), a “speech situation” is composed of “speech events”, governed directly by rules and norms of use that are shared within a community, themselves made up of “speech acts”. A central concept of pragmatics, the speech act (or communication act, or also the language act) is based on the conviction that the unit of human communication is not the sentence but the completion of certain social acts destined to modify the interlocutors’ situation. In a good number of cases, in speaking, or in writing, and with respect to his intentions of communication, the speaker resorts to language in order to, at the same time, carry out a precise action (announce a fact, take leave, give orders, pass judgment on, etc.). One describes reality and, at the same time, one acts on reality. Following such a point of view, one may estimate that the linguistic forms are not solicited in themselves, but for the social operations that they can implement in communication situations, that are often stereotypical. A Niveau-Seuil (1976: 18) regroups speech acts according to five social domains of language activity: 1) family relations; 2) professional relations; 3) gregarious relations (contact with friends, neighbors); 4) commercial and civil relations; 5) frequenting of the media. Threshold Level (1990: 8) refers more particularly to three sectors: a) “situations, including practical transactions in everyday life, requiring a largely predictable language use”; b) “situations involving personal interaction, enabling the learners to establish and to maintain social contacts, including those made in business contacts”; c) “situations involving indirect communication, requiring the understanding of the gist and/or pertaining to details of written or spoken texts”. For each act there are rules of social usage. Using speech acts that are combinations of linguistic and situational information, also signifies awareness of their degree of optionality and their possible combinations in the given cultural environment. Who should / should not, who may / may not say what? Is such and such an act optional, is its absence tolerated according ← 218 | 219 → to the norms in force? It seems essential to know which acts are likely to be articulated and combined together and, if so, in what order. For example, what are the (possible) justifications that precede or follow an information request? In a number of languages, the use of the masculine / feminine reflects the impact of social models: “lawyer, “president”, “doctor” represent – depending on the context – as much men as they do women. How are our interactions structured? In the framework of exchanges, Moeschler & Auchlin (2009: 200–201) identify – a) a series of “interventions”: immediate constituents of the exchange, and b) “discursive acts”: smaller structure units providing information that modifies the state of knowledge mutually shared by interlocutors (statement, nodding of head, shrugging of shoulders). The succession of interventions and of discursive acts, in the course of exchanges, more particularly reveals that the actors respect the role that they are in the midst of playing; e.g., “confirming exchanges” typically having a binary structure, or “repairing exchanges” serving as a remedy to language-induced ruptures, having a minimally ternary structure. In their reality, exchanges are not limited to two or three constituent systems: they result in pre-sequences, post-sequences, multiple ruptures, hesitations, extensions and variations (e.g., proposition followed by an unfavorable reaction, proposition renewal followed by a favorable reaction, etc.). The sequential structuring is infinitely more difficult to grasp in activities such as “storytelling”. Working on a corpus of “transactional” conversations held in a sewing supplies store, Moirand (1990: 72) attempts to take inventory of opening markers (“Who’s next?”, “What can I do for you?”), closing markers or markers of transactional resumption (“Will that be all”, “That will be…”), and observes to what extent it is frequent, including with new clients, for the exchange to go beyond simple transaction, to involve conjunctural elements with a barely predictable character. 5.9.3 The Most Appropriate Formulation How does one express one’s ideas through expressions that are consistent with specific contexts? How can one be aware of the game rules regarding standard behavior? How can one belong to a group? Hall raises these question (1981: 132–133), notably in observing experienced speakers ← 219 | 220 → whose exchanges are ever so swift and smooth, when they say “Two first to Land’s End returning”, instead of “Would you please sell me two round-trip tickets, first class, to Land’s End for today?” In order to express the same content, languages require a host of phrases which appear to the speaker as formulating more or less the same thing. As Bourdieu suggests (1982: 80–81), expressions that may appear substitutable (“Come!”; “Please come.”; “You will come, won’t you?”, etc.), actually are not, as each of them endeavor to attain the optimal form, following a compromise between an expressive intention and the censure imposed by a more or less dissymmetrical social relationship. Every language may elaborate its clarification expressions, aiming for conversation resumption: “excuse me, I didn’t quite catch that”, “could you repeat that, please?” In social formalism, sometimes there is only one typical expression that is suitable and which embodies all the sociologically pertinent features of the situation. One can, as such, observe that in the most diverse of languages, the reply to a question may take on the ritualized form of an admission of ignorance (Kerbrat-Orecchioni, 2005a: 93), e.g. (Table 30): Table 30: I have no idea!. The speaker seeks to retain the formulation that is the most appropriate for the communicative situation. For example, in a shop the client expresses his ← 220 | 221 → request differently depending on whether he is there for a very ordinary item (Kerbrat-Orecchioni, 2005a: 43): “Je voudrais un petit bifteck” (I’ll have some steak, please) or a product whose availability is less certain: “Vous avez des rognons de veau ?” (Would you happen to have veal kidneys?). On the basis of a corpus of interactions in a bookshop, Roulet (2005: 33–35) remarks that a bookseller does not behave in the same way if he is dealing with an isolated order, as compared to several students coming in successively to purchase the same book. Likewise, the client does not display the same behavior when he buys a book for himself, as opposed to for somebody else. The description of the actional framework necessitates not only that one define, with considerable precision, the social statuses and the respective roles of the interactants (provider or seeker of services) but also their activity program (e.g., fulfilling school obligations) and the discursive / operational organization which results from this, including non-verbal constituents. What can the pedagogical potential of such an analysis be? The non-native speaker may learn to construct and interpret sentences and texts, but does he need to acquire an “actional” competence which would allow him to carry out operations such as “entering into a bookshop”, “pay the required sum”, etc.? Does he not possess such capacities through his first language and his previous social practices? In numerous situations, the learner can, and is able to, re-exploit his actional knowledge. However, the structure of such events may vary from one cultural milieu to another. As such, language teaching cannot choose to ignore the question of the social organization of various types of discourse, beyond the inventory of their linguistic dimensions per se. 5.9.4 Prefabricated Scripts A set of raw linguistic material can become a precious object of research, notably to explain that every language possesses its own operations, allowing it to defend its ideas, to persuade its interlocutor, and to tell a story. Based on the Oral History Corpus, a large collection of spoken texts, Sealey (2010) conducted research to better understand the links between language and identity. Exploring a great variety of testimonies (144 interviews recorded in Birmingham on the occasion of the third millennium), the author firstly confirms that every person interviewed has his own “psycho-biography”. In the testimonies of men, obviously we are hardly ← 221 | 222 → surprised by the very frequent evoking of topics such as “football” and “films”, just as we might expect “children” or “nursery” to be preferred themes amongst women. This compilation of data becomes particularly interesting when it comes to the analysis of the discursive regularities likely to be observed in the “self-narration” – the latter abounding in the linguistic schemas underlying the social models. In more than 100 interviews, one finds recurrences of sequences such as “I think it was”, “I was born in”, “and I used to”, or “and we used to”. The broadening of the analysis of the combinatorics towards the discursive level is imposed: all people living in a social world are prone to have face to face or mediatized contacts with others, and during these contacts the individual tends to exteriorize a line of conduct, that is to say an outline of verbal and non-verbal acts allowing him to express his point of view on the situation. Whether or not he has the intention of adopting such a line of conduct, the individual always ends up realizing that he did indeed adopt one (Goffman, 1974: 9) because every society is based on a system of procedural practices, conventions and rules serving to orient and to organize the flow of the messages transmitted (Goffman, 1974: 32). Some submit the hypothesis that interactions are a series of, at times, complex praxeograms. These are defined as pragmatic units (Ehlich & Rehbein, 1972) or schemas of conceptual, verbal and gestural actions, governing daily or professional activities (Moirand, 1995). What does the capacity to interact consist in? What is this skill that one needs to possess, beyond knowledge that is strictly linguistic, in order to communicate efficiently? The idea that social interaction is elaborated through an ensemble of microtasks and situational constraints, that the learner needs to manage in L2 opens up promising research and pedagogical perspectives. Identifying and describing typical interactive processes initially implies minute observation of local practices as possible places of knowledge construction, as well as the micro-analysis of interactions between non-native and native speakers, for example (Pekarek Doehler, 2000). According to Gumperz (1969), defending a thesis, as a language activity, is not unlike a political activity: it involves the ability to reach a consensus on the definition of key terms. If the latter enjoy a negotiated meaning, they allow the participants to express their own point of view and that of the group without risking entering into a conflict with one another. The jury members know what, how and when something can be said. Ritualization is the fruit of the coproduction that is undertaken by ← 222 | 223 → the participants, while figuring in the mix are also the official and the informal elements (conversational resources of ordinary language: “good job”, “enjoyable”; anecdotes, private conversations, etc.), which recourse to prosodic conventions can help distinguish. If, corresponding to every type of interaction, there is a script that is specific and binding to various degrees, certain scripts (e.g., informal exchanges) at the speaker’s disposal are however reduced to vague template status, while others (more protocollike exchanges) provide the interactants with nothing more than a limited level of flexibility. As a panel of pertinent verbal and non-verbal knowledge that is proper to typical communication situations, the script “is a structure that describes appropriate sequences of events in a particular context” (Schank & Abelson, 1977: 41). The script is outlined by Dewaele (2012: 208–218) as a fairly rudimentary draft of a cinema screenplay, stocked at a conceptual level and containing possible directing instructions, and potential discourses, according to a pre-determined chronology. According to its communicative objectives, an interaction is the place of a particular category of conventionalized expressions whose aim is to convey praise, blame, support, or affection…while the force of these language acts derives, in part, from the sentiments that are projected (Goffman, 1987: 27). Whatever the culture may be, certain prefabricated scripts can be observed with relative ease. Let us consider all the scenarios of routine communication acts, bearers of conventions such as greeting, thanking, excusing oneself, authorizing, or commanding, for example, that the communities of native speakers adhere to. Language is inseparable from the performing of social practices, such as: telling a story, participating in verbal exchanges, being mutually categorized as members of a group, etc. (Pekarek Doehler, 2006). These are operations that the learner is able to carry out in his native language. It can, moreover be observed that native speakers are capable of recognizing a scenario even if there are “gaps” in the discourse sequence, while the sub-groups (e.g., social, generational, ethnic) that they form within the community may equip themselves with specific scenarios – which does not prevent them from understanding one another (Dewaele & Wourm, 2002). One example suffices here to emphasize the scope of this idea (Table 31). In races, for example, competitors are invited to take position on the ← 223 | 224 → starting line and to take off when the “starter” traditionally gives them the classic three commands, which date back to ancient Greek civilization: πόδα παρά πόδα! “poda para poda” (foot by foot), ἔτοιμοι “etimi” (ready!), άπιτε! “apité” (go!). Table 31: On your marks…!. In ordinary language usage, we may perfectly well forget one of the terms, or replace it with a gesture, and our initiated interlocutors will have no difficulty understanding us. The routine scripts that allow us to navigate without a hitch can be very different from one culture to another, and are a part of the shared knowledge of a social group. The declaration of love, for example, appears to be a particularly difficult script to acquire. Indeed, the speakers who are hardly familiar with the emotional value of the words and expressions of love in L2 risk not recognizing the launching function of the script during the first phase of courting. In an intercultural situation, the interactants may not share the same conception of the ideal script (Kerbrat-Orecchioni & Traverso, 2004). “Good morning, may I help you?” How many, even very advanced, non-native L2 learners know with certainly what the polite and ritualized response is to the vendor’s (at times insistent or wary) question, that the client is supposed to give as a “defense mechanism”: “no, thank you, I’m just looking …” = I just want to look without anybody bothering me (Table 32). Table 32: I’m just looking. As is the case with expressions of politeness, an utterance of this type, which is a part of the foreigner’s survival kit, illustrates perfectly well the cultural variations that affect the actual course of micro-acts. There is no doubt that the discursification of communication acts does not only depend ← 224 | 225 → on the specificities of the linguistic system, but is rooted in the manner in which the speakers of every community construct their representations concerning objectives and progression of this or that social micro-event. Any major deviation from the script risks disturbing the completion of an exchange project. Also, the capacity to properly manage daily interactions necessitates the sequencing mastery of speech acts. The sequences of actions and the schemas of discursive organization are, in part, common to the different languages that participate in the same cultural area. With the help of the media, one can often find the same recurring images, and the same narrative scenarios in the different western cultures: “the act of discreetly pouring poison into the glass of an enemy”, “the fact of stepping aside at the door so the ladies can pass”, “an Indian attack / those besieged put up a desperate fight / arrival at the last minute of the cavalry”, etc. (Dufays, 1997: 316– 317). However, from one language to another, events do not necessarily involve the same number of steps. The interpretation of most of the utterances supposes the knowledge of the sequence of stereotypical verbal or non-verbal actions relative to an activities’ domain. To understand the utterance “I got stranded at the airport. My visa had expired.” one has to be aware of airport formalities (Maingueneau, 2009: 113–114). Certain genres involve relatively rigid scripts: the purchase of an airline ticket, police questioning, political speech, etc. (Maingueneau, 2009: 35). The affirmation that cultural differences appear at the interaction level leads us to the hypothesis that, depending on his level, the non-native has ← 225 | 226 → the tendency to use in L2 the scripts of his native language. Foreign students who, on replicating their social models, address Professor Dominique de Salins inside a Parisian university by calling her “Mme Dominique” (de Salins, 1992: 67), do not realize that this form connotes a very specific social situation, that is demeaning in status. Knowledge of the L2 interactional norms and scripts results from our previous experience of the world. This acquired knowledge also allows anticipating and filling in the gaps during L2 learning. Ranney (1992) focuses his analysis less on speech acts than on speech events; e.g., “medical consulting”, in the course of which the non-native speakers – in this case refugees from South-Eastern Asia – marked by a traditional conception of disease and medicine, are confronted with the American medical model. Among the numerous language learning multimedia products on line, one can observe the site “Dancing with Words. Strategies for Learning Pragmatics in Spanish”, animated by the Center for Advanced Research on Language Acquisition (CARLA)4. It provides a range of resources aimed at facilitating the approach to, and the analysis of, language acts and interaction in Spanish. It is committed to capitalizing on research in pragmatics, this concept being defined as the manner in which “we convey meaning through communication.” Despite the fact that the examples focus on one particular language (and its variants), the ensemble of the program clarifies, through pedagogical commentary and pertinent examples, (e.g., strategies in greeting, thanking, apologizing, inviting, requesting, etc.), the use of language acts and ritualized expressions – the mastery of which is a delicate point in any foreign language. Knowledge of stereotypical sequences can be indispensable in grasping a message. What follows is the summary of a film cited by Maingueneau (2007: 22): “A., an ordinary-looking young veterinarian, hosts a radio program. One of her correspondents, impressed by her advice, invites her out for a drink. A, however, describes herself borrowing the features of her best friend, a striking blond. One can imagine the misunderstanding that this situation can produce …”. In order to understand this text, it is necessary to activate in one’s memory the script of radio programs (activities pursued by the radio host, flow of the programs), as well as that of flirting (having a drink, seduction operation). ← 226 | 227 → 5.9.5 Framing Sequences Gülich & Krafft (1997) draw attention to the prefabricated character of certain types of discourse (advertisements, announcements, cooking recipes, word of welcome, recommendation letters, scientific reports) comprising particular discursive structures that they call “typical texts” (formelhafte Texte), considering them as solutions that are elaborated by a social group for recurring communicative tasks purposes. The authors remark that in having recourse to preformed elements of this type of discourse, even at a very low level of L2 competence, speakers manage to produce correct sequences, sometimes without any hesitation. A typical model is an ensemble of instructions that one can choose to follow and to exploit. A discourse that is composed according to a model refers to collective knowledge concerning the production of such texts. A good number of errors can be explained through the insufficient mastery of means by which one’s ideas are structured, as well as the manner in which the relationship between the sentences is articulated. Considering that the analysis of a corpus consisting of student’s written work constitutes the surest way to apprehend interlanguage, for the implementation of a more “focused” type of teaching, Anastassiadis-Syméonidis & alii (2009: 297) propose to a group of foreign students learning Greek, in Greece, simple communicative tasks (e.g., describing their classroom to a friend who is in their country of origin). The quantitative breakdown of systematic errors in this written production corpus confirms that textual organization is “very problematic”, more particularly due to markers of connectivity. Among the most ritualized elements there are “framing” sequences that allow entry into interaction, and exit from it. The opening, pre-closing and closing of a conversation or of a written text are delicate stages: in a good number of cases, a language offers speakers ready-made and immediately reusable solutions. The opening part serves to get the interaction started, cf. ritual exchanges on time, health, etc. Meetings begin with the expression: “Let this session/meeting/deliberation, etc. open.” In emails, one can note sentences such as: “I hope all is well”, “I hope you are doing well”, “I hope everything is going well for you”, “I hope this email finds you well”, etc. The pre-closing orients the interaction towards the closing (announcing the separation, the project to meet again, etc.), while the closing marks the separation (“the meeting is ← 227 | 228 → adjourned”). The interview – strongly present in our culture – constitutes an interactional form practiced in a multiplicity of heterogeneous contexts, according to an interactional pattern which seems permanent and tends to restrict the range of communicative resources: e.g., series of adjacent question/answer pairs, variable but non-arbitrary question order, opening modalities – greetings, justification, permission request. Interviews often start with “You were born, Sir, in[…] on […]” (Dufays, 1997: 316–317). 5.9.6 The Common Mental Context Language users are alternately speakers and listeners. As such, all interaction includes both production and reception activities. The particularity of the interaction resides in the collective construction of meaning by the establishment of a common mental context. The latter notably includes ideas, sentiments, impressions, as well as expectations, in light of previous experiences, conditions and constraints that limit the choice of action (CEFR, 4.1.4. & 4.4.3.5.) The issues of genres, elaborated essentially with a view to the written word (and literature, in particular) also concern oral production. Certain exchanges, e.g., administrative, technical, official, etc., follow a relatively predictable procedure. Ordinary conversational interactions barely lend themselves to analysis in terms of discourse genre. The analysis of conversations, and in particular casual dialogue, illustrate the extreme variability of genres implemented in such exchanges. Indeed, every interactional event between two speakers is unique: all exchanges take place in a determined place and time, between specific partners who, themselves, are not identical to what they were just previously. Nothing is ever preset, even in what appears to be the most constrained of situations (Arditty & Vasseur, 2002: 254–255). One can observe that instead of speaking through mechanical turn-taking, the interactants are not passive targets: through their varied reactions, they guide, encourage or slow down one another, with respect to social rules. Interaction imposes positiontaking on a permanent basis, and a distribution (and redistribution) of the participants’ places, given the physical and mental framework in which the exchange takes place. Language production is integrated in a progressive verbal elaboration: every participant reacts to the previous manifestation, while his reaction testifies to the interpretation that he has constructed through this manifestation (Moeschler & Auchlin, 2009: 195). ← 228 | 229 → Language users adopt strategies in order to obtain the floor and to keep it, as well as to choose an adequate expression in a current repertoire of discursive functions. Having “the word” (the first and/or the last word) as a general rule signifies winning the game. Morel (2004) followed the authentic dialogue of an “inveterate speaker”, and of the “listener”, by taking into account intonative clues, as well as head and gaze movements of the two interlocutors talking in an asynchronous manner. Such an investigation aptly illustrates that “the struggle for the right to speak” is a discursive strategy, to be acquired by all non-native speakers. While taking place within a flexible framework, dialogue, a common form of interpersonal communication, is a more or less organized structure in a speech turntaking context that is dependent on the speakers’ L1 culture: “conversation is a structured activity …many speech events are very similar […] the wording may not be identical from one performance to the next, but the sequential organization is more or less constant” (Coulmas, 1981: 1 & 3). In the most varied of communication situations (in everyday life and in the language classroom), one needs a certain number of indispensable skills, both to monitor one’s own discursive actions, as well as the discursive actions and intentions of the Other. If engaging in dialogue involves the co-construction of systems dictated in a certain way by the environment, foreign language teaching should take interest in it by more particularly drawing the learners’ attention to the deeper cultural roots of the most banal of language practices, and the necessity to reflect on their naturalness. In order to succeed in constructing a conversation – the prototypical form of verbal interactions – exchanges must agree on a certain number of rules and resort to mechanisms of mutual adjustments that can be called “negotiation” (Kerbrat-Orecchioni, 2005b: 94). In every culture there are negotiation resources that preexist with respect to a given interaction. As such, respective cultures have conversation scenarios that are different. Case in point, multiple visits to a French company based in Australia, and the recording of candid office exchanges, allowed Béal (1993) to observe conversational strategies between the French and the Australians. These strategies seem to reflect specific cultural norms. For example, Australians have a tendency to close exchanges rapidly, practically without preparing the ground, while the French interlocutor is caught off guard. The closing procedures of the French tend to be elaborate and are regularly preceded by “false starts”. ← 229 | 230 → The Australian adjourns as soon as possible, thus regaining his autonomy from the exchange; he does not want to impose his presence on the other (occupy his territory) longer than is necessary. Cf. also the frequent use of expressions such as “Thanks for your time”, “Thank you. That's all I wanted to know”, etc. The phraseology of authentic conversation is a vast and evanescent reality. The nonnative, overwhelmed by the target-society’s “mechanisms of profound thought”, has little chance of spontaneously producing utterances that do not correspond between the source and target languages involved (Bidaud, 2002: 1–11): the rules governing the communicative exchanges in L1 are acquired unconsciously, through imitation,. 5.9.7 Exploring the Customary How can access be gained to the interactive wealth (with all its data and expressive options mobilizing ordinary gestures and words) that culture, down to the smallest detail, provides its speakers? “In what way can what is not shown, photographed, archived, restored, or staged, be captured?” – this is the question raised by author G. Perec (1989: 11) who is committed to recording the real, in a raw, ethnographic, manner. Regarding the most ordinary items that he calls “the infra-ordinary ”, he expresses himself thus: “What takes place every day, and recurs every day, the banal, the daily, the obvious, the common, the ordinary, the infra-ordinary, the noise in the background, the habitual – how can they be recounted, and described? As exploring the customary. For, precisely, we are used to all of this: we do not examine it, it does not make us wonder, it does not seem to pose a problem, we experience it without thinking about it […] However, how does one speak about these common thing”, how does one track them down, detect them, extract them from the mass of rock in which they are embedded, how does one lend them meaning, a language: let them speak, finally, of what is, of what we are.” In the introduction of his “Tentative d’épuisement d’un lieu parisien”, Perec (1975: 11 & 12) enumerates the main attractions of Place Saint-Sulpice (town hall, revenue service, police station, three cafés, one of which sells tobacco…), before becoming more precise: “The purpose of the following pages is rather to describe the rest: whatever one does not generally note that which is not noticed, that which has no importance: that is, whatever is happening when nothing is happening, if not time, people, automobiles and clouds”. Perec hastens to ← 230 | 231 → observe: “an old man with his demi-baguette, a lady with a pack of small pyramid-shaped cakes” (17), “pigeons flying around the square, coming back to land on the eavestroughs of the town hall” (24) while “a parish priest returns from a journey (there is an airline tag hanging from his handbag”, 25), etc. What is the knowledge range mobilized by the speaker in such and such a communication situation? Daily interaction combines with multiple elements of factual, linguistic and gestural knowledge. Galisson (1999b: 485) postulates that in every life situation there are “behavioral and verbal operations”. His objective: to find the appropriate words to say, the appropriate gestures to express, the appropriate attitudes that should be displayed at the doctor’s or in a lineup, etc. What is banal and goes without saying to the native constitutes the basic “socio-cultural viaticum” of a foreigner wishing to practice the language and culture of Another (Table 33). Table 33: Surprise! In order to illustrate these operations, socially constructed in this or that specific experiential domain, Galisson proceeds by “universe fragments” ← 231 | 232 → and attempts to reproduce the mini-process that each of them covers. Case in point: “Ordering something in a café, at the counter”: – deciding to enter, – approaching the counter, – waiting until the waiter is available, – placing the order, – consuming on the spot, – asking for the bill, – paying, – leaving, etc. (Galisson, 1991, 162–163). This genre of investigation and “theatricalization” leads to the discovery of something complex and surprisingly organized, an ensemble made up of banal and varied types of know-how: the sequencing and the realization of different phases (visible and audible) of the mini-processes are conditioned by culture. The identification of the most elementary social habits, and the mastery of series of particular verbal / non-verbal operations carrying the micro-domains of experience aim to facilitate linguistic and social insertion. 5.10 The Non-Verbal and the Paraverbal 5.10.1 The Speaking Body Communicative resources cannot be reduced to a purely linguistic corpus; they include verbal and paraverbal (physical appearance, attitudes, hand gestures, body language, facial expressions, distances, physical contact with others) or paraverbal (articulation intensity, pauses, sighs…) elements. Languages are spoken with our head, neck, eyes, hands, torso […] Culture is imprinted in our ways of speaking, and in our movements.