Uploaded by

suresamuel9

ME 414 Mechanical Measurements: Transducer Sensitivity & Error Analysis

advertisement

Content

Required

Required

Required

Required

Required

Required

Short Name

01.01

01.02

01.03

01.04

01.05

01.06

Section 01 Handouts

Original (Full) File Name

01.01_RubberBar_ForceTransducer_SensitivityExample.pdf

01.02_4‐20mA_Pressure_Transducer_Example_WSoln.pdf

01.03_PressureGage_CombinedError_Example.pdf

01.04_FourierSeries_SquareWaves_Example.pdf

01.05_FourierSeries_EvenOddFunction_Examples.pdf

01.06_FourierSeries_SquareWave_OTLab_UsingExcel.pdf

ME 414 – MECHANICAL MEASUREMENTS

Example – Rubber Block With Strain Gage – Force Transducer Sensitivity Example

A rubber bar has a single strain gage applied to it and is subjected to a load P as shown at right.

The strain gage is placed in a suitable Wheatstone bridge such that the strain measured by the

strain gage leads to an output voltage – further details of the setup are not important for this

example. The load P is increased while the Wheatstone bridge voltage is measured. The

resulting data is shown in the graph below as the open diamonds. This data has been fit with a

3rd order polynomial trendline (curve fit) whose equation and goodness of fit (R2) is shown.

We use this rubber bar as a device to measure an unknown load P applied to the bar based on

the resulting voltage (we usually call this a force transducer). Please answer the following:

a) What is the input and what is the output of this device?

b) What do we call the trendline (curve fit) of the data shown on this chart?

c) What is the sensitivity K of this device when P = 0 kN and P = 20 kN? (give units)

d) Suppose this device generates a voltage of 5.50V – estimate the load P

Load P

ME 414 – MECHANICAL MEASUREMENTS

Example – Rubber Block With Strain Gage – Force Transducer Sensitivity Example

A rubber bar has a single strain gage applied to it and is subjected to a load P as shown at right.

The strain gage is placed in a suitable Wheatstone bridge such that the strain measured by the

strain gage leads to an output voltage – further details of the setup are not important for this

example. The load P is increased while the Wheatstone bridge voltage is measured. The

resulting data is shown in the graph below as the open diamonds. This data has been fit with a

3rd order polynomial trendline (curve fit) whose equation and goodness of fit (R2) is shown.

We use this rubber bar as a device to measure an unknown load P applied to the bar based on

the resulting voltage (we usually call this a force transducer). Please answer the following:

a) What is the input and what is the output of this device?

b) What do we call the trendline (curve fit) of the data shown on this chart?

c) What is the sensitivity K of this device when P = 0 kN and P = 20 kN? (give units)

d) Suppose this device generates a voltage of 5.50V – estimate the load P

a) The load P is the input (what we are measuring) and the voltage is the output.

b) This curve fit is called the calibration curve of the instrument – relates output to input.

c) The sensitivity K is the derivative of the output relative to the input which becomes:

K

dV

d

4.6144 105 P3 5.8476 103 P 2 4.9842 101 P

dP dP

K 1.3843 104 P 2 1.1695 102 P 4.9842 101 V

P 0 K 0.49842 V

kN

;

kN

P 20 K 0.31989 V

kN

d) Read across from 5.50V and then down to estimate the load P as approximately 12.75 kN.

Load P

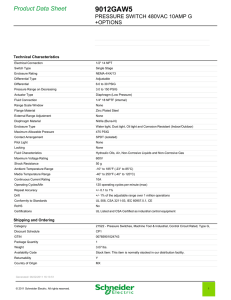

Instrument Error and Values – 4-20 mA Pressure Transducer

ME 414, Roger Bradshaw

A pressure transducer is needed to measure system pressures ranging from 0 to 120 psig

(gage pressure). Specifications for the Omega Engineering PX309 series unit are provided

on the back. The instrument needs to have a cable output and is to be used in a 4-20 mA

system; this means that full scale output (FSO) corresponds to 20 mA while 4 mA is for the

smallest output value. The measurement system example from the course slides related to

amplification and zero offset is also provided below. Please do the following:

a) State the model number for 150 psig FSO and briefly review the specifications

b) Determine the values of B and C per the equation below for the 150 psig unit

c) Determine the pressure that corresponds to a current reading of 17.2 mA

d) State the psig range for the true value corresponding to the result in part (c)

(assume ±0.25% FSO error due to linearity, hysteresis and repeatability alone)

Instrument Error and Values – 4-20 mA Pressure Transducer

ME 414, Roger Bradshaw

A pressure transducer is needed to measure system pressures ranging from 0 to 120 psig

(gage pressure). Specifications for the Omega Engineering PX309 series unit are provided

on the back. The instrument needs to have a cable output and is to be used in a 4-20 mA

system; this means that full scale output (FSO) corresponds to 20 mA while 4 mA is for the

smallest output value. The measurement system example from the course slides related to

amplification and zero offset is also provided below. Please do the following:

a) State the model number for 150 psig FSO and briefly review the specifications

b) Determine the values of B and C per the equation below for the 150 psig unit

c) Determine the pressure that corresponds to a current reading of 17.2 mA

d) State the psig range for the true value corresponding to the result in part (c)

(assume ±0.25% FSO error due to linearity, hysteresis and repeatability alone)

Note: Total error band including thermal / other errors is stated as ±1.0% FSO. If this is

applicable, the true value lies within the pressure range 122.25 – 125.25 psig.

ME 414 – MECHANICAL MEASUREMENTS

Example – Pressure Gage Combined Error Example

A pressure gage has an operating range from 0 – 200 psig. It is attached to a digital readout that reports

the pressure in increments of 0.5 psi. The manufacturer states that the pressure gage has a linearity error

of 0.15% FSO, a hysteresis error of 0.10% FSO and a sensitivity error 0.20% FSO. Assume that all

errors are intended to signify +/– error values.

Please answer the following:

a) What does FSO stand for and what it its value for this pressure gage?

b) What is the instrument uncertainty (uc) (in psig)?

c) What is the design stage uncertainty (ud) (in psig)?

d) Suppose the pressure gage digital readout reports a pressure of 144.5 psig.

What is the range of values in which the true pressure value is located?

ME 414 – MECHANICAL MEASUREMENTS

Example – Pressure Gage Combined Error Example

A pressure gage has an operating range from 0 – 200 psig. It is attached to a digital readout that reports

the pressure in increments of 0.5 psi. The manufacturer states that the pressure gage has a linearity error

of 0.15% FSO, a hysteresis error of 0.10% FSO and a sensitivity error 0.20% FSO. Assume that all

errors are intended to signify +/– error values.

Please answer the following:

a) What does FSO stand for and what it its value for this pressure gage?

b) What is the instrument uncertainty (uc) (in psig)?

c) What is the design stage uncertainty (ud) (in psig)?

d) Suppose the pressure gage digital readout reports a pressure of 144.5 psig.

What is the range of values in which the true pressure value is located?

Solution

a) FSO stands for “full scale output” – it is 200 psig for the pressure gage

b) Begin by determining the magnitude of individual error:

ulin 0.0015 200 psig

ulin 0.300 psig

uhys 0.0010 200 psig

uhys 0.200 psig

usens 0.0020 200 psig

usens 0.400 psig

Use these values to find the instrument uncertainty (uc) usingn the RSS (root-sum-squares) method:

uc

0.300 0.200 0.400 0.2900

2

2

2

uc 0.5385 psig

c) Begin by determining the zero–order uncertainty (u0). Since the resolution of the digital

readout is 0.50 psig (i.e. the readout steps in increments of 0.50 psig), this becomes:

1

u0 0.50 psig

2

u0 0.250 psig

Use this value along with the instrument uncertainty (uc) to find the design stage uncertainty (ud):

ud

0.5385 0.2500 0.3525

2

2

ud 0.5937 psig

d) The pressure gage reads 144.5 psig but the true value lies within ±ud of this value:

Readout 144.5 psig | True Value Range eadout 143.91 - 145.09 psig (rounded to 0.01 psig)

Alternate Solution

You can also do your calculations entirely using % FSO error and then convert at the end – same result:

0.15% 0.10% 0.20% 0.2693% FSO

uc 0.002693 200 psig uc 0.5385 psig

uc

2

2

2

You would need to rewrite u0 as 0.1250% FSO (= 0.250 psig / 200 psig) to continue for ud calculation:

0.2693% 0.1250% 0.2969% FSO

ud 0.002969 200 psig ud 0.5938 psig

ud

2

2

Converting Periodic Function To A Fourier Series

Roger Bradshaw, ME 414

Consider the following function that has a period T = 6 seconds It is 40 for 1 ≤ t ≤ 2 and 100 for 3 ≤ t ≤ 5 and 0 otherwise.

Plot this function over the period 0 ≤ t ≤ 6 to see what it looks like but as a single period and over several periods.

k 0 1200

110

100

90

80

70

60

f tk 50

40

30

20

10

0

10

t 0.005 k

tp 4 t 6

k

0

k

k

1

2

3

4

5

6

tk

The form of f(t) used above (not shown) is not periodic and is incorrect outside of 0 ≤ t ≤ 6. It can be made periodic by

using a "mapping time" s that converts time t to the corresponding moment in the period 0 ≤ t ≤ 6 then use f(t) as above.

s( t) t 6 floor

t

This maps any time t into the corresponsing value s in the range 0 ≤ t ≤ 6

6

The periodic function then becomes (for -6 ≤ t ≤ 18 or 4 periods total):

110

100

90

80

70

60

f s tpk 50

40

30

20

10

0

10

6

4

2

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

16

tpk

Now determine the Fourier series coefficients using the Euler formulas. Since the function is defined over the period from

0 ≤ t ≤ T, use the limits 0 to 6 in the Euler formulas (rather than -T/2 to T/2).

Substitute T = 6 and also simplify 2nπ / T = 2nπ / 6 = nπ / 3. Rrecognize that we only need to integrate from 1 to 2 (when

f(t) = 50) and from 3 to 5 (when f(t) = 100) as f(t) = 0 at all other times and the resulting integral will be 0. For A0 we find:

1

40 dt 100 dt

6

2

A0 =

1

5

3

which becomes

A0 =

1

6

( 40 200 )

or

A0 40

18

The remaining terms for An and Bn proceed similarly except the cos and sin terms complicate the integration. Use the An

and Bn expressions with the constants (40 for 1 ≤ t ≤ 2 and 100 for 3 ≤ t ≤ 5) pulled out in front of the integral. Also note

that the leading term is 2/T for An and Bn (it was 1/T for A0) - this becomes 2/6 = 1/3.

n π t

cos n π t dt

d

100

An =

40 cos

t

3

3

3

2

5

1

3

1

n π t

sin n π t dt

d

100

Bn =

40 sin

t

3

3

3

2

5

1

3

1

These are each easily evaluated to find:

An =

5 n π 5

5

2 n π sin n π

sin

sin( n π) sin

n π 2

3 2

3

3

Bn =

5

5 n π

5

n π cos 2 n π

cos( n π) cos

cos

n π 2

2

3

3

3

40

40

We can simplify a bit further by recognizing that n is an integer. Therefore sin(nπ) is always 0 and can be eliminated.

We can also simplify cos(nπ) = (-1)n since it alternates 1, -1, 1, -1, etc. We could further simplify some other terms

if we wanted (not required though). With this, we can now write each of the constants An and Bn as functions of n as:

A( n )

5 n π

5

2 n π sin n π

sin

sin

n π 2

3

3

3

where n = 1, 2, 3, ...

B( n )

5

5 n π

5

n

n π cos 2 n π

( 1 ) cos

cos

n π 2

2

3

3

3

where n = 1, 2, 3, ...

40

40

Now show each of the first 20 terms of An and Bn evaluated numerically in MathCad - these are stored in vectors Av, Bv.

i 0 30

m 0 10

Av A( r)

Bv B( r)

r

r

p 10 20

q 20 30

Av A0

r 1 30

Define each Fourier series coefficient

set as a vector (Av0 = A0, Bv0 = 0)

Bv 0

0

Define terms for plots and calcs below

0

List the first 30 terms - these are the only ones used in plot of f(t) below (note that the 10th, 20th terms are repeated):

A0To10 Av

m

B0To10 Bv

m

m

m

A10To20

B10To20

p 10

p 10

Av

Bv

p

p

A20To30

B20To30

q 20

q 20

Av

q

Bv

q

T

A0To10 ( 40.00000 27.56644 24.80980 0.00000 12.40490 5.51329 0.00000 3.93806 6.20245 0.00000 4.96196 )

T

A10To20 ( 4.96196 2.50604 0.00000 2.12050 3.54426 0.00000 3.10123 1.62156 0.00000 1.45087 2.48098 )

T

A20To30 ( 2.48098 0.00000 2.25544 1.19854 0.00000 1.10266 1.90845 0.00000 1.77213 0.95057 0.00000 )

T

B0To10 ( 0.00000 35.01409 23.87324 8.48826 11.93662 7.00282 0.00000 5.00201 5.96831 2.82942 4.77465 )

T

B10To20 ( 4.77465 3.18310 0.00000 2.69339 3.41046 1.69765 2.98416 2.05965 0.00000 1.84285 2.38732 )

T

B20To30 ( 2.38732 1.21261 2.17029 1.52235 0.00000 1.40056 1.83640 0.94314 1.70523 1.20738 0.00000 )

Note that the coefficients remain significantly non-zero even out to 30 terms. This is because of the discontinuities in

the function f(t) at t = 1, t = 2, t = 3 and t = 5. In general, discontinuous terms will require more coefficients to achieve a

good agreement with the original function due the rapid change in function value in the region of the discontinuity.

Plot the Fourier series (function fa at right) and compare to the

exact function. As defined, fa permits plots using different

numbers of terms - the first plot below is for N = 30 (used below).

N

fa( t N) A0

i π t

i π t

5

6

A(i)cos 3 B(i)sin 3

i 1

110

Exact

Fourier Series N=30

100

90

80

70

f tk

60

fa tk 30

50

40

30

20

10

0

10

0

1

2

3

4

tk

This is fairly good yet still shows some differences. For comparison, the graph below uses N =100 - much better.

110

Exact

Fourier Series N=100

100

90

80

70

f tk

60

fa tk 100

50

40

30

20

10

0

10

0

1

2

3

4

5

tk

Recall that the bunching of spikes observed in the region of the discontinuity is called "Gibbs phenomenon" (see slides).

6

Amplitude An

We refer to the collection of the Fourier series constants as a spectrum (or amplitude spectrum). Recall that each

coefficient An, Bn is associated with a certain frequency (n ω = 2 π n / T = π n / 3when expressed in rad/s). The

amplitude spectrum shows the coefficients An, Bn on the vertical axis and their associated frequency on the

horizontal axis. For the first 30 terms, this leads to the following amplitude spectrum for the An, Bn terms:

(Note: note that A0 = 40 can be thought of as occurring at a frequency of 0 (constant) but it is not shown on this graph:

14

12

10

8

6

4

2

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

16

18

20

22

24

26

28

An Value

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

16

18

20

22

24

26

28

30

32

Amplitude Bn

Frequency (n pi/3) (rad/s)

27

24

21

18

15

12

9

6

3

0

3

6

9

12

15

18

21

24

27

30

33

36

Bn Value

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

16

18

20

Frequency (n pi/3) (rad/s)

22

24

26

28

30

32

ME 414- Mechanical Measurements

To simplify the work, the work requi

integral solution is provided (easiest

to use integration by parts twice ins

J ()

tcos nt dt =

cos ( n t) + n t sin ( n

n2

0

For an even function of period T,

the Euler formulas for

the constants become:

7r

Ao == ~

J r J-1: •

2

O

.J_ ( ..!. ..I. 2) ),r

7'

.2'""

0

1i

An ~

1../

[

271

JT/2y(t)dt A,, = T4IT/2y(t')cos 2 i ,rt dt

Ao = T

711

f. cos (-z n2 .,,. d-t-

0

O

- -\ ( ,r"2.

-o )

,r

.2..

-

-

0

~4

A

'v"W\."' la.. 04.J,oo v-e p..-,"v; d~..s. ~ So Iv1'~11\. f;"' -rk ll;\..fe.(11,-~ I :a. o

_

f"' ('I -

,!_

,r

C:.O S (n._~)

-

+ t\'t S M.(~t) / 1T"'

- - n -a.

"

- ..;::fl-.. [ .::..,,s (" lT)+ n 'Tr l'>"" (nTr) -

c.., • (•)

-

~ s_, \M..P.( l~~C S tV\<..e

~ M(V\ir) -=o

a..v,..J CP .S. \l\,r '=' (- !) " O.VI. d

..f't f'I O : 0

o.~d.

~l{

_,

Co...V\.

A" :;;

:n•[(-

I) I\ -

/ ]

% - /. S ':/-o ":fA, .: -'Yr - - /. 2-1j 2

Az = o

A 3-:. - 4/91, =- - O . J"/15

II 'I =o

As-= - ~~T =- -- o, o5"o 'l

ltt, := 0

Ao =

••

I

o ~""" ( 0 )

J

[

ME 414- Mechanical Measurements

~ r: t

Fourier Series Example - Odd Function (Period T = 21t)

!o simp lify th_e w~rk, thedwdork required, the fobllo":"i~g

lfi.

l.

2,.

mtegra1 so1ut1on 1s provi e (easiest way too tam 1s

to use integration by parts twice in sequence).

. ( ) sin(nt)-ntcos(nt)

n

ft sm nt dt

===

~ .,." 0

y,

O

-K

2

For an odd function of period T,

the Euler formulas for

the constants become:

O~ t · i f

f ~t1 r

!.,...

n,

2

4

Bn = -

Jr/2

y(t)sin

T o

21tr t dt

7i 1-1 s ( 2. 11 rr-t:

) d t -= ;:

2. ['Tr

8 ,, : -'-; s

.:J .s,~ (n,t) d-b.,,.

2

,11,.

v

2. tr C

o

+w.s I I'\ re>

5KA.k.

.2.

'1 ;,~Js - -ti,.e_ .l

I Y,.

"o/:2.

0

rid, , s

.S f ll\.Ce

:sn ~ i I -c s,"'" c~) dt + ?r r o s ,~ (Y\.-t.J

'% ;'

0

' "f'ct".~I

V..~ -f-'~.e

f "° "" J.. d

ell.

s,_ ::: ;;,.,_ [ .5,.,.. (¥ ) Fa..do..-

o \A.-+

B~ =

-r:.h~[ 2

'"fh~i.e. \s

.,. 0

'Ti

V\.>

°'-'

h: C.oS ( " : " ) -

Y;z.. +o

.s1-.f l ~

:J~ ( ~

) -

niT ~ 0

t.~..

0 -

S t ~ t .. ~ ~ $ '

~ = ~ [ z sl~( rr) - 2:rr c::.~.sbr)J =

B'I =

SM.

So I \J e..

I'\• 0

«...s;

= s. (<>_)j

~ (T )]

B, = ~ [1. !>,~(1D - ir ~ s lf )] ~

f!>a ::: ~ [ .Z S 1V\ ( ~ ) - .nr

-h,

1f 0-.s.

H~O.. -+,o

c:.l~'-Y

~b-,v-e

f

t

<=.o~(¥)] :: - ~

I

so c.,.r.e a.s , ~

~

--.

-+

13.3-= -o. o;. o 'f

1~,,- [ Z s ,~ (27r) - t/1, c=..o.s. (21rJJ = - ~

~

8,s- = - o. Z~oo

Z.s,V\.(f!") - S7r ~o ~ (~")-j

_.

B5::: z~ 1i [

e.+c

d° :

l"'tt:: \ ~~-.. [

2 &,~ (

~

) -

h 1r

;r;

2

~

c,,..(~ )J s "'· rd:·

Square Wave - Fourier Series Example Using Excel

Roger Bradshaw - ME 414

Recall the square wave example at the end of the Section 01 slides from the Oscilloscope Training (OT) lab:

y t

1.40

1

1

1

1

sin 2p 1250 t sin 2p 3750 t sin 2p 6250 t sin 2p 8750 t sin 2p 11250 t

p

3

5

7

9

Suppose we want to plot the square wave using the Fourier series partial sum consisting of only 5 terms (i.e. only using

the ones show above). I typically use MathCad for such calculations but there are many other approaches. The example

below shows how to use Excel for this calculation and then plots the result to the right.

The square wave example in the textbook (Example 2.3) is an odd function so it is expressed by a Fourier sine series - the

only entries we need are the Bi terms (and, if calculated, the other terms A0 and all Ai would be 0). For the terms above

we complete the partial sum through N = 9 (i = 1 - 9) and we do not need to do anything for the even values of i since all

of the coefficients with even values of i are 0 (i.e. B2 = B4 = B6 = B8 = 0).

Begin by building a column of time values spanning one period - in this case, I will use -T/2 to T/2 to look like the

textbook example. The frequency of the square wave in the OT lab is 1250 Hz (cycles/second) which corresponds to a

period T= 0.00080 seconds/cycle (= 1/1250). To avoid very small numbers, the time column below is expressed in

-3

milliseconds (1 ms = 10 s) - these will be divided by 1000 to convert to seconds for the functions. Use enough points to

accurately capture the nature of the curve - in this case, I used 401 points evenly spaced between -0.40 ms and 0.40 ms.

Now build a column for each term in the Fourier sine series. The first row is the value of i for each column. The second

row is the amplitude Bi for each column and it is given by 1.40 / (i p) - for the OT lab, the units of the square wave were

volts so that will the units of each Bi term. The second row is the frequency fi (in Hz) for each term in the Fourier sine

series - it is simply the base frequency (1250 Hz) multiplied by i. Excel does it sine and cosine calcutions in radians [check

sin(p/4) = 0.7071... to verify this if you like] so the 3rd row is the frequency in wi in radians/second (simply multiply fi by

2p).

Now evaluate each term in the Fourier sine series individually (each one in its own column). The function in each column

is Bi sin (wi t) where t is the time value in the leftmost column (divide by 1000 to convert to seconds). The rightmost

column adds the columns for each of the individual sine terms to complete the summation. This is plotted on the right.

You could do additional terms in the Fourier sine series by simply adding more columns.

i

Bi (V)

1

0.44563

3

0.14854

5

0.08913

7

0.06366

9

0.04951

fi (Hz)

1250.0

3750.0

6250.0

8750.0

11250.0

wi (rad/s)

Time t (ms)

-0.40000

-0.39800

-0.39600

-0.39400

-0.39200

7854.0

y1

0.00000

-0.00700

-0.01400

-0.02099

-0.02798

23561.9

y3

0.00000

-0.00700

-0.01398

-0.02093

-0.02783

54977.9

y7

0.00000

-0.00699

-0.01389

-0.02062

-0.02711

70685.8

y9

0.00000

-0.00698

-0.01381

-0.02038

-0.02653

Sum y

0.000

-0.035

-0.070

-0.104

-0.137

0.39200

0.39400

0.39600

0.39800

0.40000

0.02798

0.02099

0.01400

0.00700

0.00000

0.02783

0.02093

0.01398

0.00700

0.00000

39269.9

y5

0.00000

-0.00699

-0.01394

-0.02081

-0.02754

…

0.02754

0.02081

0.01394

0.00699

0.00000

0.02711

0.02062

0.01389

0.00699

0.00000

0.02653

0.02038

0.01381

0.00698

0.00000

0.137

0.104

0.070

0.035

0.000

OT Lab Square Wave (Partial Sum N = 9)

0.500

0.400

0.300

Voltage (V)

0.200

0.100

0.000

-0.100

-0.200

-0.300

-0.400

-0.500

-0.40

-0.30

-0.20

-0.10

0.00

Time (ms)

0.10

0.20

0.30

0.40

Oscilloscope Training (OT) Lab – Square Wave

Oscilloscope Training (OT) lab has several sections

• Steps 48 – 57 perform Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) on a square wave

• Square wave is 1250 Hz (T = 0.80 ms) with 700 mVpp and a 50% duty cycle

(half of the time it is –0.350 V and half of the time it is +0.350 V)

• Textbook Example 2.4 – square wave, modify to get Fourier series for above

(textbook: period is 10 s, 2 Vpp | OT lab: period 0.00080 s, 0.7 Vpp)

y t

1.40

1

1

1

1

sin 2 1250 t sin 2 3750 t sin 2 6250 t sin 2 8750 t sin 2 11250 t

3

5

7

9

1250 Hz

3750 Hz

6250 Hz 8750 Hz 11250 Hz

1-52

1