Uploaded by

muhtadyahnaf

The Worlds of the Fifteenth Century: Global Civilizations & Columbus's Impact

advertisement

C H A P T E R

1

2

T h e W o r l d s o f the

Fifteenth C e n t u r y

The Shapes o f Human Communities

Paleolithic Persistence: Australia and

North America

Agricultural Village Societies: The

Igbo and the Iroquois

Pastoral Peoples: Central Asia and

West Africa

Civilizations of the Fifteenth

Century: Comparing China and

Europe

?Columbus was a perpetrator o f genocide

.

. . , a slave trader, a thief,

a pirate, and most certainly n o t a hero. To celebrate Columbus is to

congratulate the process and history of the invasion.? This was the

view of Winona LaDuke, president of the Indigenous Women's Netw o r k , on the occasion in 1992 of t h e 500th anniversary o f Columbus?s arrival in the Americas. Much of t h e commentary surrounding

t h e event echoed t h e same themes, citing t h e history o f death, slavery, racism, and exploitation t h a t f o l l o w e d in t h e w a k e o f Columbus's

Ming Dynasty China

first voyage t o w h a t was f o r him an altogether New W o r l d . A century

European Comparisons: State

Building and Cultural Renewal

earlier, in 1892, t h e t o n e o f celebration had been very different. A

European Comparisons: Maritime

Voyaging

Civilizations of the Fifteenth

Century: The Islamic World

In the Islamic Heartland: The

Ottoman and Safavid Empires

On the Frontiers of Islam: The

Songhay and Mughal Empires

Civilizations of the Fifteenth

Century: The Americas

The Aztec Empire

The Inca Empire

Webs of Connection

A Preview of Coming Attractions:

Looking Ahead t o the Modern

Era, 1500-2015

Reflections: What If? Chance and

Contingency in World History

Zooming In: Zheng He, China's

Non-Chinese Admiral

Zooming In: 1453 in Constantinople

Working w i t h Evidence: Islam and

Renaissance Europe

presidential proclamation cited Columbus as a brave ?pioneer o f

progress and enlightenment? and instructed Americans t o ?express

h o n o r to the discoverer and their appreciation o f t h e great achievements of four completed centuries o f American life.? The century t h a t

f o l l o w e d witnessed the erosion of Western d o m i n a n c e in t h e w o r l d

and the discrediting of racism and imperialism and, w i t h it, t h e reputation o f Columbus.

his sharp reversal o f opinion about Columbus provides a

reminder that the past is as unpredictable as the future. Few

Americans in 1892 could have guessed that their daring hero could

emerge so tarnished only a century later. A n d few people living in

1492 could have imagined the enormous global processes set i n

motion by the voyage o f Columbus?s three small s h i p s ? t h e Atlantic slave trade, the decimation o f the native peoples o f the A m e r i cas, the massive growth o f w o r l d population, the Industrial R e v o -

lution, and the growing prominence o f Europeans on the w o r l d

stage. N o n e o f these developments were even remotely foreseeable

in 1492.

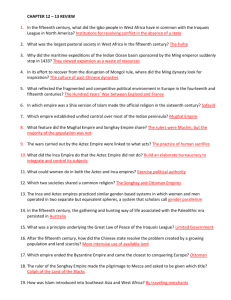

The Meeting of Two Worlds = This n ineteenth-century painting shows Columbus on his first voyage to the New World. He

is reassuring his anxious sailors by pointing to the first sight of land. In light of its long-range consequences, this voyage represents a major turning point in world history.

499

500

CHAPTER 12 / THE WORLDS OF THE FIFTEENTH CENTURY

£ Columbus was arguably the single

Thus, i n historical hindsight, that voyage © B u t i t was n o t the o n l y significant

most i m p o r t a n t event o f the fifteenth century.

m a r k e r o f that century. A C e n t r a l Asian T u r k i c w a r r i o r

n a m e d T i m u r l a u n c h e d the

sia e m e r g e d f r o m t w o cen-

s o n o f a d j a c e n t c i v i l i z a t i o n s . R uusss i a

j o r pastoral invasio

y

ao d i n g p r o j e c t across n o r t h e r n A c i n

:

turies o f M o n g o l rule to begin a huge empire~

.

+

last m a

.

.

.

ge

*

3

A n e w European i u i l i z a t i o n was taking shape i n the R e n a s s a n

In 1405, a n

enormous Chinese fleet, d w a r f i n g that o f C o l u m b u s ,s e t o u t across the o n e Indian

Ocean basin, o n l y to v o l u n t a r i l y w i t h d r a w t w e n t y - e i g h t years later. T h e Islamic

O t t o m a n E m p i r e p u t a final end t o C h r i s t i a n B y z a n t i u m w i t h t h e

Constantinople i n 1453, even as Spanish Christians c o m p l e t e d the

c o n q u e s t of

reconquest

of

the Iberian Peninsula f r o m the M u s l i m s i n 1492. A n d i n t h e A m e r i c a s , theA z t e c

and Inca empires gavea final and spectacular expression t o M e s o a m e r i c a n and

A n d e a n civilizations before they were b o t h s w a l l o w e d u p i n t h e b u r s t o f European

imperialism that f o l l o w e d the arrival o f C o l u m b u s .

Because the fifteenth century was a hinge o f major historical change on many

fronts, it provides an occasion f o r a bird?s-eye view o f the world

througha kind o f global tour. This excursion around the world

____

f

W h a t predictions about the future

might a global t r a v e l e r in the fif-

teenth century have reasonably

made?

-cibapbssinitaat

w i l l serve to briefly review the human saga thus far and to

~

§

{

:

.

establish a baseline from w h i c h the enormous transformations

of the centuries that followed m i g h t be measured. H o w , then,

might we describe the world, and the worlds, o f the fifteenth

century?

The Shapes o f H u m a n C o m m u n i t i e s

One way to describe the world o f the fifteenth century is to identify the various

types o f societies that it contained. Bands o f hunters and gatherers, villages o f agricultural peoples, newly emerging chiefdoms or small states, pastoral communities

established civilizations and e m p i r e s ? a l l o f these social or political formsw o u l d

have been apparent to a widely traveled visitor i n the fifteenth century. Representing alternative ways o f organizing human life, all o f them were l o n g established by

the fifteenth century, but the balance among these distinctive kinds o f societies in

1500 was quite different than it had been a thousand years earlier

P a l e o l i t h i c Persistence: A u s t r a l i a a n d N o r t h A m e r i c a

Despitem i l e n a o f agricultural advance, substantial areas o f the w o r l d still hosted

gathering and hunting societies, k n o w n to historians as Paleolithic ( O l d Stone Age)

P e n

t

a U of

A m

Australia, m u c h o f Siberia, t h e arctic coastlands, a n d parts o f Africa

}

?

:

bygone age?They t00 hat che weed ony These peoples were not simply relics of a

.

ad

changed

o v e r time, , t h o u ggh h m o r e slowly th

cultural counterparts, and they too interacted w i t h their neighbors

had

.

h o e?hey

a hihistory, although most history books largely ignore them after the age

ad a

.

of agri-

:

THE SHAPES OF H U M A N C O M M U N I T I E S

501

A M A P OF T I M E

1345-1521

A z t e c E m p i r e in M e s o a m e r i c a

" 1368-1644 Ming dynasty in China

rne

e

4 370-1405

Conquests o f T i m u r

15th c e n t u r y

Spread o f Islam in Southeast Asia

Civil w a r a m o n g Japanese w a r l o r d s

Rise o f H i n d u state o f Vijayanagara in southern India

E u r o p e a n Renaissance

F l o u r i s h i n g o f A f r i c a n states o f Ethiopia, K o n g o , Benin,

Zimbabwe

can t

1405-1 4 3 3

1415

1438-1533

1453

1464-1591

1492

n

e

ce

e n

Nee t e

B e g i n n i n g o f Portuguese e x p l o r a t i o n o f West African coast

I n c a E m p i r e a l o n g t h e Andes

O t t o m a n seizure o f C o n s t a n t i n o p l e

S o n g h a y E m p i r e in W e s t Africa

C h r i s t i a n r e c o n q u e s t o f Spain f r o m Muslims completed;

Columbus's first transatlantic voyage

pa

n

1497-1520s

e

Chinese m a r i t i m e voyages

n

e

m

t

a

Portuguese e n t r y into the IndianO c e a n w o r l d

1501

F o u n d i n g o f Safavid E m p i r e in Persia

1526

F o u n d i n g o f M u g h a l E m p i r e in India

culture arrived. Nonetheless, this most ancient way o f life still had a sizable and

variable presence i n the w o r l d o f the fifteenth century.

Consider, f o r example, Australia. That continent?s many separate groups, some

250 o f them, still practiced a gathering and hunting way o f life i n the fifteenth century, a pattern that continued well after Europeans arrived i n the late eighteenth

century. O v e r many thousands o f years, these people had assimilated various material items o r cultural practices from o u t s i odu ter i gr gse r canoes, fishhooks, com?

plex nettirig techniques, artistic styles, rituals, and mythological i d e a s ? b u t despite

the presence o f farmers i n nearby N e w Guinea, no agricultural practices penetrated

the Australian mainland. Was it because large areas o f Australia were unsuited for

the k i n d o f agriculture practiced in N e w Guinea? O r did the peoples o f Australia,

enjoying an environment o f sufficient resources, simply see no need to change their

w a y o f life?

.

.

Despite the absence o f agriculture, Australia?s peoples hadmastered and manipulated their environment, in part through the practice o f ?firestick farming,? a

pattern o f deliberately set fires, which they described as ?cleaning up the country.?

@

Comparison

In what ways did the gath-

ering and hunting people of

Australia differ from those

of the northwest coast of

North America?

502

CH

APTER 12 / THE WORLDS OF THE FIFTEENTH CENTURY

These controlled burns served to clear the underbrush, thus a t i n g v l i d o n e n s ii e

and encouraging the g r o w t h o f certain plant and animal P e

° dredso f

i ,

Australians exchanged goods among themselves o v e t distances 4 u n ,

? es,

created elaborate mythologies and ritual practices, and develope h e , 8h e t trabasis o f

ditions o f sculpture and r o c k painting. T h e y accomplisheda l l o f this o n

cee

the

an e c o n o m y and t e c h n o l o g y r o o t e d i n the distantP a l e o l i t h i c past.

hed

in

th

A very different k i n d o f gathering and h u n t i n g society flourishe

. the f i f .

t e e n t h c e n t u r y along the northwest coast o f N o r t h A m e r i c a a m o n g ene Cl inookan,

T u l a l i p , Skagit, and other peoples. W i t h some 3 0 0 edible a n i m a l species and an

abundance o f salmon and other fish, this extraordinarily b o u n t e o u s o c e a n

p r o v i d e d the f o u n d a t i o n for w h a t scholars sometimes call ?complex? o r ?affluent?

g a t h e r i n g and h u n t i n g cultures. W h a t distinguished the n o r t h w e s t coast peoples

f r o m those o f Australia w e r e permanent village settlements w i t h large a n d sturdy

houses, considerable e c o n o m i c specialization, r a n k e d societies t h a t sometimes

i n c l u d e d slavery, chiefdoms dominated by p o w e r f u l clan leaders o r ?big men,? and

?ay:

extensive storage o f food.

A l t h o u g h these and other gathering and h u n t i n g peoples persisted still i n the

fifteenth century, both their numbers and the area they inhabited had contracted

greatly as the Agricultural Revolution unfolded across the planet. That relentless

advance o f the farming frontier continued in the centuries ahead as the Russian,

Chinese, and European empires encompassed the lands o f the remaining Paleolithic

peoples. By the early twenty-first century, what was once the only human way of

life had been reduced to minuscule pockets o f people whose cultures seemed

doomed toa f i n a l extinction.

Agricultural Village Societies: The Igbo and the Iroquois

Far more numerous than gatherers and hunters were those many peoples who,

though fully agricultural, had avoided incorporation into larger empires or civilizations and had not developed their o w n city- or state-based societies. L i v i n g usually

i n small village-based communities and organized i n terms o f kinship relations, such

people predominated during the fifteenth century i n m u c h o f N o r t h America; in

most o f the tropical lowlands o f South America and the Caribbean; in parts o f the

Amazon R i v e r basin, Southeast Asia, and Africa south o f the equator; and througho u t Pacific Oceania. Historians have largely relegated such societies to the

periph-

© perip

ery of warld history,

ye

viewing, them as marginal to the cities, states, and large-scale

civilizations that predominate in most accounts of the global past. Viewed from

m Change

What kinds of changes

.

were transformingt h e societies o f the West African

Igbo and the North Ameri.

can jroquois aS the fifteenth

century unfolded?

w i t h i n their own circles, though, these societies were at the center o f things each

w i t h its o w n history o f migration, cultural tran

s f o r m a t i o n , social c o n f l i c t , i n c o r p o -

ration o f new people, political rise and fall,

and interaction with strangers. In short,

they too changed as their histories took sh

ape.

en

Niger Raver in the heavily forested region o f West Africa lay the

of she Igbo (EE-boh) peoples, By the fifteenth century, their neighbors, the

ps

of

he

503

THE SHAPES OF H U M A N C O M M U N I T I E S

Yoruba and Bini, had begun to develop small states and urban centers. But the

Igbo, whose dense population and extensive trading networks might well have

given rise to states, declined to follow suit. The deliberate Igbo preference was to

reject the kingship and state-building efforts o f their neighbors. They boasted on

occasion that ?the Igbo have no kings.? Instead, they relied on other institutions to

maintain social cohesion beyond the level o f the village: title societies in which

wealthy men receiveda series o f prestigious ranks, women?s associations, hereditary ritual experts serving as mediators, and a balance o f power among kinship

groups. It was a ?stateless society,? famously described in Chinua Achebe?s

Things Fall Apart, the most widely read novel to emerge from twentiethcentury Africa.

But the Igbo peoples and their neighbors did not live in isolated, selfcontained societies. They traded actively among themselves and w i t h more

distant peoples, such as the large Aftican kingdom o f Songhay (sahn-GEYE)

far to the north. Cotton cloth, fish, copper and iron goods, decorative

objects, and more drew neighboring peoples into networks o f exchange.

C o m m o n artistic traditions reflected a measure o f cultural unity in a

politically fragmented region, and all o f these peoples seem to have

changed from a matrilineal to a patrilineal system o f tracing their descent.

Little o f this registered i n the larger civilizations o f the Afro-Eurasian

world, b u t to the peoples o f the West African forest during the fifteenth

A

4 a 4 N. \

;

century, these processes were central to their history and their dailylives. Soon, however, all o f them w o u l d be caught up in the transatlantic

slave trade and w o u l d be changed substantially in the process.

Across the Atlantic i n what is n o w central N e w Y o r k State, other agricultural village societies were also in the process o f substantial change during the several centuries preceding their incorporation into European trading

networks and empires. The Iroquois-speaking peoples o f that region had only

recently become fully agricultural, adopting maize- and bean-farming techniques

that had originated centuries earlier in Mesoamerica. As this productive agriculture

took hold by 1300 o r so, the population grew, the size o f settlements increased, and

distinct peoples emerged. Frequent warfare also erupted among them. Some schol-

Igbo A r t

Widely known for their masks,

used in a variety of ritual and

ceremonial occasions, the Igbo

were also among the first to

ars have speculated that as agriculture, largely seen as women?s w o r k , became the

produce bronze castings using

the ?lost wax? method. This

primary economic activity, ?warfare replaced successful food getting as the avenue

to male prestige.?

exquisite bronze pendant in the

form of a human head derives

Whatever caused it, this increased level o f conflict among Iroquois peoples triggered a remarkable political innovation around the fifteenth century: a loose alliance

or confederation among five Iroquois-speaking p e o p l e s ? t h e M o h a w k , Oneida,

Onondaga, Cayuga, and Seneca. Based on an agreement k n o w n as the Great Law

o f Peace (see M a p 12.5, page 523), the Five Nations, as they called themselves,

agreed to settle their differences peacefully through a confederation council o f clan

leaders, some fifty o f them altogether, w h o had the authority to adjudicatedisputes

and set reparation payments. Operating by consensus, the Iroquois League o f Five

from the Igbo Ukwu archeological site in eastern Nigeria and

dates t o the ninth century c.e.

(The British Museum, London, UK/

Werner Forman/Art Resource, NY)

504

CHAPTE

R 12 / THE WORLDS OF THE FIFTEENTH CENTURY

Nations effectively suppressed the blood feuds and tribal conflicts that had only

r e c e n t l y been so widespread. I t also coordinated their peoples? r e l a t i o n s h i p W i t h

outsiders, i n c l u d i n g the Europeans, w h o arrived i n g r o w i n g numbers i n the centuries after 1500.

es o f limited government, social

gave expression to valu

The Iroquois League

equality,a n d nersonalfreedom, concepts that some European colonists foundhighly

attractive. One British colonial administrator declared i n 1749 that the Iroquois

had ?such absolute Notions o f Liberty that they allow noK i n d of Superiority of

one over another, and banish all Servitude from their Territories.?* Such equality

extended to gender relationships, for among the Iroquois, descent was matrilineal

(reckoned through the woman?s line), married couples lived w i t h the wife?s family,

and w o m e n controlled agriculture and property. While men were hunters, warriors, and the primary political officeholders, women selected and could depose

those leaders.

Wherever they lived in 1500, over the next several centuries independent agricultural peoples such as the Iroquois and Igbo were increasingly encompassed in

expanding economic networks and conquest empires based i n Western Europe,

Russia, China, o r India. In this respect, they replicated the experience o f many other

village-based farming communities that had much earlier found themselves forcibly

included in the powerful embrace o f Egyptian, Mesopotamian, Roman, Indian,

Chinese, and other civilizations.

Pastoral Peoples: Central Asia and West Africa

Pastoral peoples had long impinged more directly and dramatically on civilizations

than did hunting and gathering or agricultural village societies. T h e M o n g o l incursion, along w i t h the enormous empire to which it gave rise, was one in a l o n g series

o f challenges from the steppes, but it was not quite the last. As the M o n g o l Empire

disintegrated, a brief attempt to restore it occurred i n the late fourteenth and early

fifteenth centuries under the leadership o f a T u r k i c warrior named T i m u r , bom

i n what is n o w Uzbekistan and k n o w n in the West as Tamerlane (see Map 12.1,

m@

Significance

What role did Central Asian

and West African pastoralists play in their respective

regions?

page 506).

W i t h a ferocity that matched or exceeded that o f his model, Chinggis Khan,

Timur?s army o f pastoralists brought immense devastation yet again to Russia,

Persia, and India. T i m u r himself died in 1405, while preparing for an invasion of

China. Conflicts among his successors prevented any lasting empire, although his

descendants retained control o f the area between Persia and Afghanistan for the rest

o f the fifteenth century. That state hosted a sophisticated elite culture, combining

T u r k i c and Persian elements, particularly at its splendid capital o f Samarkand, as its

rulers patronized artists, poets, traders, and craftsmen. Timur?s conquest proved to

be the last great military success o f pastoral peoples f r o m Central Asia. In the cent u r i e st h a tf o l l o w e d , their homelands were swallowed up i n the expanding Russian

and Chinese empires, as the balance o f power between steppe pastoralists o f inne!

Eurasia and the civilizations o f outer Eurasia turned decisively i n favor o f the latter.

C I V I L I Z A T I O N S OF THE FIFTEENTH C E N T U R Y : C O M P A R I N G C H I N A A N D E U R O P E

I n Africa, pastoral peoples stayed independent o f established empires several

centuries longer than those o f Inner Asia, f o r n o t until the late nineteenth century

were they incorporated into European colonial states. The experience o f the Fulbe,

West Africa?s largest pastoral society, provides an example o f an African herding

people w i t h a highly significant role in the fifteenth century and beyond. From

their homeland i n the western fringe o f the Sahara along the upper Senegal River,

the Fulbe had migrated gradually eastward i n the centuries after 1000 c.g. (seeM a p

12.3, page 514). U n l i k e the pastoral peoples o f Inner Asia, they generally lived

i n small communities among agricultural peoples and paid various grazing fees and

taxes f o r the privilege o f pasturing their cattle. Relations w i t h their farming hosts

often w e r e tense because the Fulbe resented their subordination to agricultural

peoples, whose w a y o f life they despised. That sense o f cultural superiority became

even more p r o n o u n c e d as the Fulbe, i n the course o f their eastward m o v e m e n t ,

slowly adopted Islam. Some o f t h e m i n fact d r o p p e d o u t o f a pastoral life and settled

i n towns, w h e r e t h e y became highly respected religious leaders. In the eighteenth

and nineteenth centuries, the Fulbe were at the center o f a wave o f religiously

based uprisings, o r jihads, w h i c h greatly expanded the practice o f Islam and gave

rise to a series o f n e w states, ruled b y the Fulbe themselves.

Civilizations o f the Fifteenth Century:

C o m p a r i n g C h i n a and Europe

B e y o n d the foraging, farming, and pastoral societies o f the fifteenth-century w o r l d

were its civilizations, those city-centered and state-based societies that w e r e far

larger and m o r e densely populated, more p o w e r f u l and innovative, and m u c h m o r e

unequal in terms o f class and gender than other forms o f human c o m m u n i t y . Since

the First C i v i l i z a t i o n s had emerged between 3500 and 1000 B.c.z., b o t h t h e geographic space they encompassed and the n u m b e r o f people they embraced had

g r o w n substantially. B y the fifteenth century, a considerable majority o f the world?s

population lived w i t h i n one o r another o f these civilizations, although most o f these

_people no d o u b t identified m o r e w i t h local communities than w i t ha larger civilization. W h a t m i g h t an imaginary global traveler notice about the world?s major c i v i lizations in the fifteenth century?

M i n g Dynasty China

Such a traveler m i g h t well begin his o r her j o u r n e y i n China, heir to a l o n g tradition

o f effective governance, Confucian and Daoist philosophy, a major Buddhist presence, sophisticated artistic achievements, and a highly productive economy. T h a t

civilization, h o w e v e r , had been greatly disrupted b y a c e n t u r y o f M o n g o l rule, and

its p o p u l a t i o n had been sharply reduced b y the plague.

During

t h e Min

(1368-1644), however, C h i n a recovered (see M a p 12.1). T h e early decades o f that

dynasty witnessed a n e f f o r t toeliminate a l lS igns ¢o f foreign rule, discouraging the

u s oef Mongol names and dress, while promoting Confucian leat ninga n d orthodox

? ?

?

?

?

505

506

C H A P T E R 1 2 , THE W O R L D S OF THE FIFTEENTH C E N T U R Y

Gh ?"

PACIFIC

TAIWAN O C E A N

A r a b i a n

S e a

MALDIVE: |

ISLAN|

u

.

I N D I A N

O C E A N

[ [ _ ] M i n g dynasty C h i n a

Timur?s e m p i r e about 1405

H B

Delhi Sultanate

Vijayanagara

?

M a p 12.1

Routes of M i n g dynasty voyages

Asia in the Fifteenth Century

The f i f t e e n t h century in Asia witnessed t h e massive M i n g dynasty voyages i n t o t h e Indian Ocean,

the last major eruption of pastoral power in Timur?s empire, and the flourishing of the maritime city

of Malacca.

gender roles, based o n earlier models f r o m the Han, Tang, and Song dynasties.

E m p e r o r Yongle ( Y A H N G - l e h ) (r. 1402-1422) sponsored an enormous Encyclopedia o f some 11,000 volumes. W i t h contributions f r o m more than 2,000 scholars,

this w o r k sought to summarize or compile all previous w r i t i n g o n history, geography, philosophy, ethics, government, and more. Y o n g l e also relocated the capital

to Beijing, ordered the building o f a magnificent imperial residence k n o w n as the

Forbidden C i t y , and constructed the Temple o f Heaven, where subsequent rulers

performed Confucian-based rituals to ensure the w e l l - b e i n g o f Chinese society.

T w o empresses wrote instructions for female behavior, emphasizing traditional

expectations after the disruptions o f the previous cent

China was l o o k i n g to its past.

ury. C u l t u r a l l y speaking,

;

a

pescription

id you define the

~ How wou

major achievements of

China?

Politically, the

dynasty r e e s t a b l i s h e d t h e c i v i l s e r v i c e e x a m i n a t i o n system

Mi

that

n had

e been

g l e c u nt d e reMongol

d

i z e d government. Po

tule and went on to create a highly central:

n n e of - r o w e r was concentrated in the hands o f the emperor himself,

(castrated men) personally loyal to the emperor exercised

w

1

Oe

chs

50 7

CIVILIZATIONS OF THE FIFTEENTH CENTURY: COMPARING CHINA A N D EUROPE

great authority, m u c h to the dismay o f the official bureaucrats. The state acted vigorously to repair the damage o f the M o n g o l years by restoring millions o f acres to

cultivation; rebuilding canals, reservoirs, and irrigation works; and planting, according to some estimates, a billion trees in an effort to reforest China. Asa result, the

economy rebounded, both international and domestic trade flourished, and the

population grew. D u r i n g the fifteenth century, China had recovered and was perhaps the best governed and most prosperous o f the world?s major civilizations.

China also undertook the largest and most impressive maritime expeditions

the w o r l d had ever seen. Since the eleventh century, Chinese sailors and traders

had been a major presence in the South China Sea and i n Southeast Asian port cities, w i t h m u c h o f this activity in private hands. B u t now, after decades o f preparation, an enormous fleet, commissioned by Emperor Yongle himself, was launched

in 1405, f o l l o w e d over the next t w e n t y - e i g h t

years by six more such expeditions. O n board

more than 300 ships o f the first voyage was a

crew o f some 27,000, including 180 physicians, hundreds o f government officials, 5

astrologers, 7 h i g h - r a n k i n g o r grand eunuchs,

carpenters, tailors, accountants, merchants,

translators, cooks, and thousands o f soldiers

and sailors. Visiting many ports in Southeast

Asia, Indonesia, India, Arabia, and EastA f r i c a ,

these fleets, captained by the M u s l i m eunuch

Z h e n g H e ( U H N G - h u h ) , sought to enroll

distant peoples and states in the Chinese t r i b ute system (see M a p 12.1). Dozens o f rulers

accompanied the fleets back to China, where

they presented tribute, performed the required

rituals o f submission, and received i n return

abundant gifts, titles, and trading o p p o r t u nities. Chinese officials were amused b y some

o f the exotic products to be found a b r o a d ?

ne

oe

*

?

m

i

Dey

x]

.

ostriches, zebras, and giraffes, f o r example.

Officially described as ?bringing order to the

world,? Z h e n g He?s expeditions served to

establish Chinese p o w e r and prestige in the

Indian Ocean and to exert Chinese control

over foreign trade in the region. T h e Chinese,

however, did n o t seek to conquer new terri-

Temple of Heaven

tories, establish Chinese settlements, o r spread

early fifteenth century. in Chinese thinking,

|

t h e i r c u l t u r e , t h ough t h ey d i d intervene i n

a

n u m b e r o f local disputes. (See Z o o m i n g In:

Z h e n g H e , page 508.)

set ina forest of more than 650 acres, the

Temple of Heaven was constructed in the

inn

it was the primary place where Heaven

and Earth met. From his residence in the Forbidden City, the Chinese emperor led a

imploredthe g t s f o r e g e e a i n e e e o t S sacred site, where he offered sacrifices,

performed the rituals that maintained the

cosmic balance. (Imaginechina for AP Images)

mane.

508

life.

his

the

of

trajectory

this

have

Zheng

surely

in

a in

He for

the

aof

decisively

altered

China's turning

point

major

not

had

history

end

the

of

Mongol

coincided

with

His

resistwas

father

own

killed

rule.

tradition

continued

century.

would

devout father

to

had

and

his now

Both

the who

what

Asia Central

family

in

his

pilgrimage

Mecca.

made

Mongol

China

rulers

local

also

had

The

high family

serving

prominence

officials

as

achieved

Muslims

were

grandfather

is

in

Uzbekistan.

were

roots

China,

southwestem

Yunnan region

person

named

unusual

frontier

1371

Born Zheng

He.*

the

in

of in

in

aearly A of

the

the

in

century

most

was

fifteenth

helm

massive

China?s

expeditions

Maritime

it

Zheng

birth,

He's

as

happened,

The

as

he his

also

than Zheng

his

he

But

lost

their along

and

was

Ming

that

the

the

He

with

He Zheng

ing

in

a a lost

from the

of

of

in

becoming

castration,

eunuch.

underwent

organs

sex

male

freedom;

more

Chrispractice

China

history

long

well

as

had

supporters.

Muslim

young

Mongols

prisoner

hundreds

taken

Mongols

1382.

dynasty

ousted

forces

new

Eleven-year-old

Yunnan

world

a

khad

hundred

years,?

ever

ex

allowed

and

this

and

enormous

China?s

Non-Chinese

they

authoritie:

Chinese

1433,

After

ended.

were

seen

officials

Many

long

the

had

high-ranking

enterprise.

because

was

believed,

China,

self-suficie

the

they

resources

African

giraffe.

a?

emperor

\ordered

nown

been

who

Yongle,

death

into

had

had

involved

the

theitself

historian

recent

wrote

extinction

t of

interest

Chinese

court

excited

none

more Among

the

an He?s

than

Zheng

the

in

expeditions,

of

Zheng

He,

acquisitions

of

Admiral

deliberately

abruptly

voyages

surprising

was

these

feature

most

and

how

The

NY

of

Philadelphia

Resource,

(1977-42-1)/The

Museum

Art/Art

photo:

Giraffe

Dynasty

Tribe

China,

1414,

Ming

with

and

the

his

the

of

confidence

eventually

master,

(1368-1644),

Attendant,

won

John

on

and

of

ink

T.

(1403-1424),

the

almost

eunuch

himself

in proved

an

skirmishes

various

military

against

Mongols

leader

Dotrance,

Yongle

1977

Period

silk/Gift

color

He

Chinese

northern

around

soon

region

Zheng

Beijing.

effective

seven-foot-tall

deteriorate

port.

than

less

fleet

pensive

?In

to

in

wealth.

and

prestige,

of

greatest

voyages,

navy

?the

these

the

then

the

in

establishing

himself

s

expeditions

stopped

simply

such

nt

kingdom,?

?middle

of of

civil

shaped

was

the

of trading

their

for

possibility

power,

achieving

castration,

After

pure

chance

his

Chinese

voluntarily

men

became

eunuchs,

manhood

China?s

Strangely

service.

the

at

officials,

especially

central

substantial

numbers

enough,

Zheng

as

He?s

life

who

the

of

Di,

Zhu

to

the he

emperor,

reigning

was

assigned

son

fourth

imperial

court,

utter

their

where

theemperor

of

gained

the upon

loyalty

the

and

to

hostility

scholar~bureaucrats

lion

eunuchs

served

Chinese

the(1368-1644),

civilizations.

tian

Islamic

and

1mil. of

dynasty

years

someDuring

Ming

276

the

the

number

powerful

became

Asmall

members

emperor

and

elite,

the

of

enduring

themdependence

chief

Part

as

the

he the

a of

of

of?>

peditions

waste

patron

reason

a

elephants,

ostriches,

giraffe.

lions,

zebras,

and

empire

maritime

Indian

Ocean

basin.

the

in

they

But and

also

world

have

1433

and

the

role

his

2,000

Once

of

in

led

largely

effort

no

with

those

or going.

to

mold

an

not

punish

or

who

Chihe

the

for

to Zheng

trade,

on

force

used

knew

While

in

a of

of

in he piracy

a

He

ally

he and

his

he of

for

history.

something

revealed

man

his religion

he

age

hardly

Thus

that

not

Islamic

since

lived

in

the

at

he

his

adopted

ioft setting

is

a

in

voyage

During

Ceylon,

mon

China.

third

gifts

a

trilingual

recording

praise

erected

tablet

lavish

and

surprising

eleven.

posture

eclectic

more

coward

com-

the

capture

primarily

with

to

fascinating,

court

retuming

imperial

found

China

Zheng

also

He?s

The

relivoyages

changing

disclose

exotica

interior

eye

keen Ceylon.

had

also

He

kind

the

that

against

soldiers

miler

hostile

the

the

personally

overtures.

nese

Chinese

suppress

resisted

colonies

establish

peaceful,

occasions

several

control

journeys

were

was

where

in

Columbus,

ususailed

waters

well-traveled

fHe

ar

Zheng

himself

found

more

soon

with

But

?huge

of a

assignment

commander

China's

ambitious

Chinese

defined

himself.

Clearly,

explorer

was

than

blue

to

the

lower-ranking

assigned

eunuchs.

one

the

he

rather

robe,

could

Now

don

red

prestigious

vants.

voyages

Zheng

1405

between

seven

The

that

led

He

With

his

in as

of as

the

that

to

Zhu

civil

and

Di

the

in

Palace

Director

served

Zheng

SerGrand

as

first

He

Yongle

emperor,

emperor

master

1402.

power

brought

war

In

deliberately

large-scale

Philippines,

Taiwan, prevailed,

voices

Chinese

private

merchants

Chinese

craftsproject

eunuchs,

court

these

whom

despised.

officials

from

they

from

their

real

back

turned

what

surely

was

within

Asia,

support

without

their

state men

settle

Japan,

trade

andvoyages

as

as north,

Even

the

the little

the

the

to

quite

reach

on

itsgovernment.

they

but

so

did

the

The

to

and

the

andthese

the

the

?itsa of in of of

Chinese continued

Southeast

officialdom

constantly

barbarians

where

Finally,

threatened,

viewed

requiring

outside

eyes,

danger

world.

came

China

the

in

present.

shape

lite?

tion

his

AND

509

THE

OF

COMPARING

CIVILIZATIONS

EUROPE

CENTURY:

CHINA

FIFTEENTH

hfe.

his

an

of

In

meaning

insenption

own

essenoal

describe

Questions;

Zheng

might

How

life?

He's

of

arc

the

you

What

castraZheng

points?

tuming

major

were

He's

How

its

did

symbol

poution

global

growing

China's

peaceful

ways,

such potent

as century,

however,

resurrected voyages.

remarkable

past

Zheng

first

been rwenty-

a He

has the

those

carly

rely

and

their

in pure

and

could

of

In of

led

ihad

n unusual

Zheng

the

after

But

the

from

record,

largety

counrry

his

and

1¢

a3

about

forgot

even

from

we

the

thn,

sea,

most

who

man

a

cal

the

s He

tChinese

hande his

of

and

its

the

ts

intentions.

appropriated,

proves

distorted,

tomenmes

useful

withdrew

death,

vamshed

hisron-

upon

safety.?

them formgn

became

peaceful

pcuples

pursue

occupations

recklessly

routes

sea

Because

extermunated.

barbanan

countries,

kings

ressted

who

transformation

prior

just

Zheng

last

his

to

He

voyage.

erected

summa-

the

at

his

foreign

arnved

?When

rized

we

achievernents:

He

his

the

to

of

journeys

succes

credited

Zheng

the

said

relic

And

ain

be

to

of

the

a

Buddha.

tooth

famous

and

Allah.

form

local

to

the

the

to

to

aHindu

of

Buddha,

510

CH

A P T E R 12 / THE W O R L D S OF THE FIFTEENTH CENTURY

European Comparisons:

State Building and Cultural Renewal

A t the other end o f the Eurasian continent, similar processes o f demographic recov.

ery, p o l i t i c a l consolidation, cultural flowering, and overseas expansion were under

way. Western Europe, having escaped M o n g o l conquest b u t devastated by the

plague, began to r e g r o w its p o p u l a t i o n during the second h a l f o f thef i f t e e n t h cent u r y . As i n C h i n a , the infrastructure o f civilization p r o v e d a durable f o u n d a t i o n for

@ Comparison

W h a t political and cultural

differences stand o u t in

t h e histories of fifteenth-

d e m o g r a p h i c and e c o n o m i c revival.

Politically too Europe j o i n e d C h i n a in c o n t i n u i n g earlier patterns o f state building. In C h i n a , h o w e v e r , this meant a unitary and centralized g o v e r n m e n t that

encompassed almost the w h o l e o f its civilization, w h i l e i n E u r o p e a d e c i d e d l y frag-

Europe? W h a t similarities

m e n t e d system o f m a n y separate, independent, and h i g h l y c o m p e t i t i v e states made

f o r a sharply d i v i d e d Western civilization (see M a p 12.2). M a n y o f these s t a t e?s

are apparent?

Spain, Portugal, France, England, the city-states o f Italy ( M i l a n , V e n i c e , and Flor-

c e n t u r y China and Western

ence), various G e r m a np r i n c i p a l i t i e s ?learned

to tax t h e i r citizens m o r e efficiently,

t o create m o r e effective administrative structures, and to raise s t a n d i n g armies. A

small Russian state centered o n the city o f M o s c o w also e m e r g e d i n the fifteenth

c e n t u r y as M o n g o l rule faded away. M u c h o f this state b u i l d i n g was d r i v e n b y the

needs o f war, a frequent occurrence i n such a fragmented and c o m p e t i t i v e political

e n v i r o n m e n t . England and France, for example, f o u g h t i n t e r m i t t e n t l y f o r more

t h a n a c e n t u r y i n the H u n d r e d Years? W a r ( 1 3 3 7 - 1 4 5 3 ) o v e r r i v a l claims to territ o r y in France. N o t h i n g remotely similar disturbed the i n t e r n a l l i f e o f M i n g dynasty

China.

A renewed cultural blossoming, known in European history as the Renaissance,

likewise paralleled the revival o f all things Confucian in M i n g dynasty China. In

Europe, however, that blossoming celebrated and reclaimed a classical GrecoRoman tradition that earlier had been lost or obscured. Beginning in the vibrant

commercial cities o f Italy between roughly 1350 and 1500, the Renaissance

reflected the belief o f the wealthy male elite that they were living in a wholly new

era, far removed from the confined religious world o f feudal Europe. Educated citizens o f these cities sought inspiration in the art and literature o f ancient Greece and

Romie; they were ?returning to the sources,? as they put it. Their purpose was not

so much to reconcile these works with the ideas o f Christianity, as the twelfth- and

thirteenth-century university scholars had done, but to use them as a cultural standard to imitate and then to surpass. The elite patronized great Renaissance artists

such as Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Raphael, whose paintings and sculptures were far more naturalistic, particularly in portraying the human body, than

those o f their medieval counterparts. Some o f these artists looked to the Islamic

world for standards o f excellence, sophistication, and abundance. (See Working

w i t h Evidence: Islam and Renaissance Europe, page 536.)

A l t h o u g h religious themes remained p r o m i n e n t , Renaissance artists n o w included

p o r t r a i t s and busts o f w e l l - k n o w n c o n t e m p o r a r y figures, scenes f r o m ancient

CIVILIZATIONS OF THE FIFTEENTH CENTURY: COMPARING CHINA AND EUROPE

ATLANTIC

OCEAN

Corsic

s e i n e

_. 2 ° ? NORTH AFRIGA-~

abet

i g

M e d i t e r r a n e a n

Sea

L 7 °

M a p 12.2

Europe in 1500

By the end o f the fifteenth century, Christian Europe had assumed its early modern political shape

@5 a s y s t e

of competing states threatened by an expanding Muslim Ottoman Empire.

mythology, and depictions o f Islamic splendor. In the work o f scholars, k n o w n as

humanists, reflections on secular topics such as grammar, history, politics, poetry,

thetoric, and ethics complemented more religious matters. For example, Niccold

Machiavelli?s (1469-1527) famous work The Prince was a prescription for political

success based on the way politics actually operated in a highly competitive Italy o f

rival city-states rather than on idealistic and religiously based principles. T o the

question o f whether a prince should be feared or loved, Machiavelli replied:

O n e ought to be both feared and loved, b u t as it is difficult for the t w o to go

together, it is m u c h safer to be feared than loved.

.

.

.

For it may be said o f men

in general that they are ungrateful, voluble, dissemblers, anxious to avoid danger,

511

512

C H A P T E R 12 / THE W O R L D S OF THE FIFTEENT

H CENTURY

The W a l d s e e m i i l l e r M a p of 1507

which was created by the German

Just fifteen years after Columbus landed in the Western Hemisphere, this map,

f the planet's global dimensions and

cartographer Martin Waldseemiiller, reflected a dawning European awareness 0

the location of the world?s major landmasses.

(bpk, Berlin/Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, Stiftung PreussischerKulturbesitz/Photo:

Ruth Schacht/Art Resource, NY)

and covetous o f gain.

.

. . Fear is maintained by dread o f punishment w h i c h never

fails. . . . In the actions o f men, and especially o f princes, f r o m w h i c h there is

no appeal, the end justifies the means.®

While the great majority o f Renaissance writers and artists were men, among

the remarkable exceptions to that rule was Christine de Pizan (1363-1430), the

daughter o f a Venetian official, who lived mostly i n Paris. H e r writings pushed

against the misogyny of so many European thinkers o f the time. In her City of

Ladies, she mobilized numerous women from history, Christian and pagan alike, to

demonstrate that women too could be active members o f society and deserved an

education equal to that of men. Aiding in the construction o f this allegorical city is

Lady Reason, who offers to assist Christine in dispelling her poor opinion o f her

own sex. ?No matter which way I looked at it,? she wrote, ?I could find no evidence from my own experience to bear out such a negative view o f female nature

and habits. Even so . . . 1 could scarcely find a moral work by

didn?tdevote some chapter or paragraph to attacking the femal

any

hich

or W

auth

y _

H e a v i l y influenced by classical models, Renaissance fi

€ Sex.

?sance

ested i n capturing the unique qualiti

figures were m o r e i n t e r .

UnIqUe

describing

qt ities o f particular individuals and

th

-_

world as it was than in portraying or explori

in describing te

ploring eternal religious truths. In its focus

in

CIVILIZATIONS OF THE FIFTEENTH CENTURY: COMPARING CHINA AND EUROPE

513

on the affairs o f this world, Renaissance culture reflected the urban bustle and commercial preoccupations o f Italian cities. Its secular elements challenged the otherworldliness o f Christian culture, and its individualism signaled the dawning o f a

more capitalist economy o f private entrepreneurs. A new Europe was in the making,

one more different from its own recent past than M i n g dynasty China was from its

pre-Mongol glory.

European Comparisons: MaritimeVoyaging

A global traveler during the fifteenth century might be surprised to find that Europeans, like the Chinese, were also launching outward-bound maritime expeditions.

Initiated in 1415 by the small country o f Portugal, those voyages sailed ever farther

down the west coast o f Africa, supported by the state and blessed by the pope (see

Map 12.3). As the century ended, two expeditions marked major breakthroughs,

although few suspected it at the time. In 1492, Christopher Columbus, funded by

Spain, Portugal?s neighbor and rival, made his way west across the Atlantic hoping

to arrive in the East and, in one o f history?s most consequential mistakes, ran into

the Americas. Five years later, in 1497, Vasco da Gama launched a voyage that took

him around the tip o f South Africa, along the East African coast, and, w i t h the help

o f a Muslim pilot, across the Indian Ocean to Calicut in southern India.

The differences between the Chinese and European oceangoing ventures were

striking, most notably perhaps i n terms o f size. Columbus captained three ships and

a crew o f about 90, while da Gama had four ships, manned by perhaps 170 sailors.

These were minuscule fleets compared to Zheng He?s hundreds o f ships and a crew

in the many thousands. ?All the ships o f Columbus and da Gama combined,?

according to a recent account, ?could have been stored ona single deck o f a single

vessel in the fleet that set sail under Zheng He.?8

Motivation as well as size differentiated the two ventures. Europeans were seeking the wealth o f Africa and Asia? gold, spices, silk, and more. They also were i n

search o f Christian converts and o f possible Christian allies w i t h w h o m to continue

their long crusading struggle against threatening Muslim powers. China, by contrast,

faced no equivalent power, needed no military allies i n the Indian Ocean basin, and

required little that these regions produced. N o r did China possess an impulse to

convert foreigners to its culture or religion, as the Europeans surely did. Furthermore, the confident and overwhelmingly powerful Chinese fleet sought neither

conquests nor colonies, while the Europeans soon tried to monopolize by force the

commerce o f the Indian Ocean and violently carved out huge empires in the

Americas.

T h e most s t r i k i n g difference i n these t w o cases lay i n the sharp contrast b e t w e e n

China?s decisive e n d i n g o f its voyages and the c o n t i n u i n g , indeed escalating, E u r o pean effort, w h i c h soon b r o u g h t the world?s oceans and g r o w i n g numbers o f the

world?s people u n d e r its c o n t r o l . T h i s is w h y Z h e n g He?s voyages w e r e so l o n g

neglected i n China?s historical m e m o r y . T h e y led n o w h e r e , whereas the i n i t i a l

@ Comparison

In what ways did European

maritime voyaging in the

fifteenth century differ

from that of China?

What accounts for these

differences?

514

CHAP

TER 12 / THE WORLDS OF THE FIFTEENTH CENTURY

.

Sem!

M e d i t e r r a n e a n Sea

5 . Mogadishu

at

Ake

v i rr y

,

o n$82)

) )

at

Mombasa

i?

alindi

(1498)

Lake

BANTU-SPEAKING

(1498)

?glanganyika?.

ZIMBABY

MWENE-MUITAPA

KALAHARI

DESERT

< =

Portuguese voyages o f exploration

< = = Chinese m a r i t i m e voyages to EastA f r i c a

< =

M o v e m e n t o f Fulbe people

Map 12.3

=

Africa in the Fifteenth Century

By the fifteenth

:

century, / Africa was a virtual museum

iti

of political

and cul

iversi

*

ing large empires, such as Songhay; smaller kingdoms, such as Kongo; s t y states cmon othe Yoruba,

1

Hausa,a n d Swan peoples; village-based societies w i t h o u t States ata l l as among the i bo; and

pastoral peoples, such as the Fulbe. Both European and Chinesemaritime expeditions touched on

Africa during that century,: even as Islam conti n

continent.

ued to find acceptance in the northern half of the

European expeditions, so much smaller and less promisi

were but the first step?

on a journey to world power. But why did the Euro ine

peans continue a process that

the Chinese had deliberately abandoned?

In the first place, Europe h

.

werinhee ad no unified political authority w i t h the power °

an

order

end to its

utreach. Its system o f competing states, so unlike

?

C I V I L I Z A T I O N S OF THE FIFTEENTH CENTURY: THE I S L A M I C W O R L D

China?s single unified empire, ensured that once begun, rivalry alone would drive

the Europeans to the ends o f the earth. Beyond this, much o f Europe?s elite had an

interest in Overseas expansion. Its budding merchant communities saw opportunity

for profit; its competing monarchs eyed the revenue from taxing overseas trade o r

from seizing overseas resources; the Church foresaw the possibility o f widespread

conversion; impoverished nobles might imagine fame and fortune abroad. InC h i n a ,

by contrast, support for Zheng He?s voyages was very shallow in official circles, and

when the emperor Yongle passed from the scene, those opposed to the voyages

prevailed within the politics o f the court.

Finally, the Chinese were very much aware o f their own antiquity, believed

strongly in the absolute superiority o f their culture, and felt with good reason that,

should they desire something from abroad, others would bring it to them. Europeans too believed themselves unique, particularly in religious terms as the possessors

o f Christianity, the ?one true religion.? In material terms, though, they were seeking out the greater riches o f the East, and they were highly conscious that Muslim

power blocked easy access to these treasures and posed a military and religious threat

to Europe itself. All o f this propelled continuing European expansion in the centuries that followed.

The Chinese withdrawal from the Indian Ocean actually facilitated the European entry. It cleared the way for the Portuguese to penetrate the region, where

they faced only the eventual naval power o f the Ottomans..Had Vasco da Gama

encountered Zheng He?s massive fleet as his four small ships sailed into Asian waters

in 1498, world history may well have taken quite a different turn. As it was, h o w ever, China?s abandonment o f oceanic voyaging and Europe?s embrace o f the seas

marked different responses to a common problem that both civilizations s h a r e?d

growing populations and land shortage. In the centuries that followed, China?s ricebased agriculture was able to expand production internally by more intensive use o f

the land, while the country?s territorial expansion was inland toward Central Asia.

By contrast, Europe?s agriculture, based on wheat and livestock, expanded primarily by acquiring new lands i n overseas possessions, which were gained as a consequence o f a commitment to oceanic expansion.

Civilizations o f the Fifteenth Century:

T h e Islamic W o r l d

Beyond the domains o f Chinese and European civilization, our fifteenth-century

global traveler would surely have been impressed w i t h the transformations o f the

Islamic world. Stretching across much o f Afro-Eurasia, the enormous realm o f

Islam experienced a set o f remarkable changes during the fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, as well as the continuation o f earlier patterns. The most notable

change lay in the political realm, for an Islamic civilization that had been severely

fragmented since at least 900 now crystallized into four major states or empires (see

Map 12.4). A t the same time, a long-term process o f conversion to Islam continued

515

516

CHAPTER 12 / THE WORLDS OF THE FIFTEENTH CENT

URY

t h w i t h i n a n d b e y o n d these

?oti

he

transformation o f A f r o - E u r a s i a n societies b o

cultural

t h e cultural t r a n s t o r m

n e w states.

.

In the Islamic Heartland:

The Ottoman and Safavid Emptres

?-

states was the Ottoman

T h e most impressive and e n d i n g Ot

from e a v o u r t e e n t h to the early twen-

W h a t differences can you

Empire, w h i c h lasted i n one form o r anothe!

N s o n y T u r k i c w a r r i o r groups that

identify among the four

major empires in the tslamic

world of the fifteenth and

sixteenth centuries?

tieth century. I t was the creation o f one 0 i thy. i n the sever.al centuries follow.

had migrated into Anatolia, slowly and sporaaic ceoman vrarks had already carved

@ Comparison

i n g 1000 c.£. B y the mid-fifteenth century, these e e n i n s u l a and had pushed deep

o u t a state that encompassed m u c h o f theA n a t o

h e process 2 substantial C h r i s

into southeastern Europe (the Balkans); S o e t h e O t t o m a n E m p i r e extended its

Africa,

tian population, D u n n g the sixteenth o N

the lands s u r r o u n d i n g the

c o n t r o l to much o f the M i d d l e East, coastal N o r t h

ca,

j

rope.

BlackSea, a n v e spire w s

vateo f n o e n o u s significance i n thew o r l d o f the

fifteenth century and beyond. In its huge territory, l o n g duration, i n c o r p o

m a n y diverse peoples, and economic and cultural sophistication, it v e

on

i

o e

great empires o f w o r l d history. In the fifteenth century, o n l y M i n g y e s t

and the Incas matched it i n terms o f wealth, p o w e r , and splendor. T h e empire

represented the emergence o f the Turks as the d o m i n a n t people o f the Islamic

w o r l d , ruling n o w over many Arabs, who had initiated this n e wf a i t h morethan

800 years before. In adding ?caliph? (successor to the Prophet) t o t h e i r other titles,

O t t o m a n sultans claimed the legacy o f the earlier Abbasid E m p i r e . T h e y sought to

b r i n g a renewed unity to the Islamic world, while also serving as p r o t e c t o r o f the

faith, the ?strong sword o f Islam.?

The Ottoman Empire also represented a new phase in the long encounter between

Christendom and the world of Islam. In the Crusades, Europeans had taken the

aggressive initiative in that encounter, but the rise of the Ottoman Empire reversed

their roles. The seizure of Constantinople in 1453 marked the final demise o f Chnistian Byzantium and allowed Ottoman rulers to see themselves as successors to the

Roman Empire. (See Zooming In: 1453 in Constantinople, page 518.) Italso opened

the way to further expansion in heartland Europe, and in 1529a rapidly expanding

Ottoman Empire laid siege to Vienna in the heart of Central Europe. The political

and military expansion o f Islam, at the expense o f Christendom, seemed clearly undef

way. Many Europeans spoke fearfully of the ?terror o f the Turk.?

In the neighboring Persian lands to the east of the Ottoman Empire, another

Islamic state was also taking shape in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centur i e s ? t h e Safavid (SAH-fah-vihd) Empire. Its leadership was also Turkic, but in

this case it had emerged from a Sufi religious order founded several centuries eatliet

by Safi al-Din (1252-1334). The long-term significance o f the Safavid Empire,

which was established in the decade following 1500, was its decision to forcibly

C I V I L I Z A T I O N S OF THE FIFTEENTH CENTURY: THE I S L A M I C W O R L D

0

5 0 0 ? - 1,000 m i l e s

0

500 1,000 kilometers

M a p 12.4

Empires of the Islamic World

The most prominent political features of the vast Islamic world in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries were f o u r large states: the Songhay, Ottoman, Safavid, and Mughal empires.

impose a Shia version o f Islam as the official religion o f the state. Over time, this

form o f Islam gained popular support and came to define the unique identity o f

Persian (Iranian) culture.

This Shia empire also introduceda sharp divide into the political and religious

life o f heartland Islam, for almost all o f Persia?s neighbors practiced a Sunni form o f

the faith. For a century (1534-1639), periodic military conflict erupted between

the Ottoman and Safavid empires, reflecting both territorial rivalry and sharp religious differences. In 1514, the Ottoman sultan wrote to the Safavid ruler in the

most bitter o f terms:

You have denied the sanctity of divine l a w ... you have deserted the path of

salvation and the sacred commandments... you have opened to Muslims the

gates o f tyranny and oppression . . . you have raised the standard of irreligion

517

518

the

of

ascendency

Ottoman

to

all

Roman,

chings

had

heir

more

shrunk

the

than

little

to

city

1453,

that steady

the

By

of

Ottomans.

advance

empire,

once-great

Empire

been

had

certain

inevitathe retreating

for Byzantine

about acquired

bility

the

air

Empire.

event

this

for

the

and

Empire

Byzantine

nople,

marked

event

that

the

end an

final

the

of

Roman/

it, aof In

before

two

centuries

almost

great

city

II

of

of the

retrospect,

Mehined

control

seized

Christian

Constanti-

29,

O May

of

:

forces

1453,

the

Ottoman

Muslim

sultan

hoped

more,

assistance

very

end,

until

had

the sieges.

he

for

great

sides

on

third,

two

on

many

and

wall

had

and by

a

water

repeatedly

withstood

attacks

Further-

protected

aware

odds

faced.

city,

great

his

Yet

great

vast

amid

effort

human

with

and

uncertainty

the

he

of

So

in

ithet

in

about

was

1453.

outcome.

Constantinople

last

well

XI,

the

emperor,

Byzantine

Constantine

was

only

itself,

50,000

active

8,000

only

with

and

some

inhabitants

On

othe

f

Frontiers

Islam:

and

Empires

Mughal

Songhay

The

has

to

|the

hostility

continued

Sunni/Shia

divide

This

in

1453.

Constantinople

firstthe

century.

twenty:

the

and

aand

pronounced

[Therefore]

...

senhave

doctors

heresy.

our

alana

Image

photo:

Works

bild/The

ullstein

©

Turks

walls

the

.of

Ottoman

storm

to

to

himself

one

going

back

the

who

Muhammad

a

of

Doing

city.

also

could

him

the

so

rid

conquered

very

not

as

regarded

promising.

Furthermore,

some

II, aof

Ottoman

1451,

new

came

sultan

throne

to

the

only

old the

prophesies

promised

mined

honor young

Islamic

detersultan

gain

to

the

the

in onBut

among

court

officials

about

attack

the

had

an

Constantinople.

seemed

Mehmed

nineteen

Empire,

years

widely

and

reservations

of

In

no

promising

union

with

the

assurance

success.

ensured

that

Constantinople

effort

with

mous

expended

was

Ottoman

enorside,

the

On

ofof

andthe

the

in

half

the

blasphemer.?

tence century

fifteenth

perjurer

you,

against

death

Empire

Songhay

nas,

second

rose

eae e e e e n e

The

such

no

make

But

help

at it,

to

though

to

of probfleet

of

afrom a least

not

in

powers

Western

lems

the

between

OrthoEastern

Catholicism

Roman tility

doxy

and

as

hosgs

well

the

long-standing

persisted.

internal

arrived,Roman

Church

obtain

difference,

rumors

Venice

Western

even

Christians,

from

quantities

sufficient

:its

would

meet

alone.

end

c e e

project.

offer

finally

but

the

he

seriously,

declaring,

refused,

evening,

emperor

Byzantine

ordered

about

relics

icons

entered

the

Holy

and Sophia,

sins

his

the procession

then

and

for

seeking

church

ancient

the

Hagia

for- city

giveness

receiving

Communion.

of began

early

then,

And

final

day,

the

forces

walls

as

the

Constantinople

breached

Ottoman

of of a

Christian

next

assaule

have

?We

will.?

free

our

with

die

to

all

a an

of

After

of

decided

own

declared

May

day

on

had

28.

descended

Mehmed

prayer

and

rest

next

assaule

final

before

That

day.

the

the

if

apparently

Constantine

surrendered.

considered

they

furious

weeks

silence

bombardiment,

onunous

to

the

his

spare

emperor

people

offered

times

three

and

expensive

simply

pay

very

not

could

afford

this

to

for

law,

for

As

by

fifty-seven

Islamic

Mehmed

days.

required

number

could

which

one

huge

hurl

control

cannon

constructed

named

builder

Orban,

had

the

on

a

sequently

devastating

surroundeffect

walls

late

to

toy and

bIn

began

on

an

so

And

for

and huge

fleet,

a

city.

aThe the

Constantinople

water.

access

ter

a who

of

a

cannons,

first

who

the

to

his

emperor,

Byzantine

offered

services

materials,

constructed

gathered

fortress

men

the

a

of

Hungarian

Mehmed

1452,

services

massecured

preparations

assault

once-great

assembled

Ottomans

Leo

as

city

the

of

Africanus

remarked

Timbuktu:

known

on

and

style

and

early

the

tohad

the

Ali to

aofinvisaaand

atohisalso

benjoyed

in

u r for

its

of

(r.

by

A ible

ain ofof of

aa

in

routes

much

derived

revelargest

impressive

recent

most

series

operated

states

crucial

trade

that

and

thei

and

that

at

that

but the

the

commerce

century.

sixteenth

Songhay

Nonetheless,

enemies.

become

center

Islamic

reputation

magician

possessed

thought

charm

render

soldiers

fasted

proper

Ramadan

Islamic1465-1492),

religious

behavior

fifteenth-century

Sonniaccounts

monarch

largely

limited

urban

culeural

This

elites.

Songhay

divide

largely

withintaxing

from

nue

growing

Islam

was

Songhay

faith

was

learning

North

African

traveler

their

major

as

gave

who

during

alms

commerce.

intersection

crans-Saharan

It

.the

i

ifteenth

was

possible?

THE

THE

OF

519

CIVILIZATIONS

WORLD

ISLAMIC

CENTURY:

FIFTEENTH

had

that

the

occurred.

destruction

retake

city

the

for

to

Teappear

Chnstendom.

a

what

different

might

been

have

circumstances

outcome

massacred

any

longer

no

was

there

and

had

resstance,

the in

of

the and

A

a

between

Christendom.

world

that

and

Islam

change

relanonship

occurred

mosque.

Ottoman

became

had

Empire,

Sophia

Haga

Hagia

wept

altar

tian

at

Chnisat men,

the

che

he

monks,

When killing,

taking

town

of city.

Sophia,

reportedly

seeing

momentous

to

What

Under

Questions:

contributed

factors

victory?

Mehmed?s

of

capital

city,

a

the

Constanunople

Mushm

now

was

praying

entered

himself

Mehmed

captive

pness.""?

children,

women,

raping,

disrobing,

pillaging,

stealing,

to

marble

into

cured

that

buried

and

from

him angels

plundering

one

so,

Even

limited

aftermath

day.

the

he

a

in

nearby

eventually

would

which

cave

of

plundering

Mehmed

reluctant,

was

spoils,

days

the

but

Constanune

took

and

their

like

The

the

2 his city.

A

suggested

soldier.

legend

fighting

later regalia

discarded

Constantine

royal

city,

died

and

common

Chnstians

defended

bravely

C H A P T E R 12 / T H E W O R L D S OF THE F I F T E E N T H C E N T U R Y

Ottoman Janissaries

the Janissaries became the elite infantry force of the Ottoman Empire. ComOriginating in the fourteenth century,

d marching music, they were the first standing army in the region since the days

an

plete with uniforms, cash salaries,

of the Roman Empire. When gunpowder technology became available, Janissary force s soon were armed with muskets, grenades, and handheld cannons. This Turkish miniature painting dates from the sixteenth century. (Turkish

miniature, Topkapi Palace Library, Istanbul, Turkey/Album/Art Resource, NY)

Here are great numbers o f [Muslim] religious teachers, judges, scholars, and

o t h e r learned persons w h o are b o u n t i f u l l y maintained at the king?s expense.

H e r e too are brought various manuscripts o r w r i t t e n books f r o m Barbary

( N o r t h Africa] w h i c h are sold for more money than any o t h e r merchandise.. .

.

Here are very rich merchants and to here j o u r n e y c o n t i n u a l l y large n u m b e r s

o f negroes w h o purchase here cloth f r o m Barbary and Europe..

.

. It is a w o n -

d e r to see the quality o f merchandise that is daily b r o u g h t here and h o w costly

and sumptuous everything is."!

See W o r k i n g with Evidence, Source 7.3, page 318, for more from Leo Africanus

about West Africa in the early sixteenth century. Sonni Ali?s successor made the

pilgrimage to Mecca and asked to be given the title ?Caliph o f the Land o f the

Blacks.? Songhay then represented a substantial Islamic state on the African frontier