Uploaded by

Jerome Cardillo

Basic Statistical Concepts: Introduction to Statistics & Data Types

advertisement

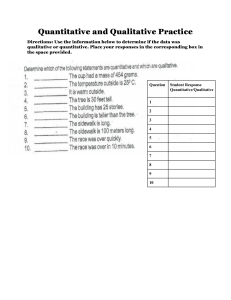

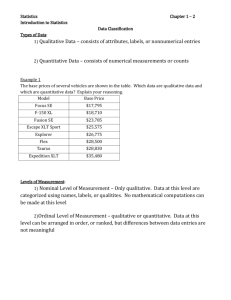

LESSON 1: Basic Statistical Concepts 1.1 CONCEPTS AND NATURE OF STATISTICS The purpose of this lesson is to convince the learner that information resulting from a good statistical analysis is always concise, often, precise and never useless! The spirit of statistics is, in fact, very well captured by the quotation from John Maynard Keynes “It is better to be roughly right than precisely wrong”. Statistics is a science that helps us make better decisions in business and economics, as well as, in the other fields. Today, the field of statistics is widely recognized as an important tool for testing concepts and for perceiving new directions in various fields of specialization. Almost daily, we take “educated guesses” concerning the future events in our lives in order to plan new situations or experiences. As these experiences occur, we are sometimes able to confirm or support our ideas. In some other times, however, we are not so lucky and must experience some unpleasant consequences. Sometimes we win, sometimes we lose. Thus, we must make a sound investment in the stock market, but so sorry about our voting decision; win money at a game, but discover we have taken the wrong medicine for our illness; do well on a final exam, but have a miserable defense of the marketing plan. We now need statistical thinking, or the ability to weigh the merits of different options based on whatever available data we have. Statistical analysis often involves an attempt to generalize from the data. Our data are summarized, displayed in meaningful ways and analyzed. Deriving statistical information requires tedious work and boring descriptions of society and nature by means of a set of numbers. The collection, organization, presentation, analysis and interpretation of numerical data must be done with accuracy and precision in order to arrive at a valid and reliable statistical information. Actually, without noticing it, people often apply statistics in their everyday lives. A worker in any field, such as education, social sciences, behavioral sciences, applied sciences, engineering, research, business and economics, is expected to have at least statistical literacy. Today, college students in almost all disciplines, including business and economics are required to take at least one statistics subject. In fact, it is virtually impossible to practice one’s profession without a minimal understanding of statistics. In business and economics, statistics plays an important role in market feasibility studies for new products, forecasting of business trends, control and maintenance of high-quality products, improvement of employer-employee relationship and analysis of data concerning insurance, investment, sales, employment, transportation, communication, auditing and accounting procedures. In research, methods for statistical design of surveys and experiments are valuable to researchers. Causes and effects of factors affecting experiments may lead to discoveries which have to be supported by statistical data obtained from repeated trials. 1.2 DEFINITION OF STATISTICS Statistics is defined as a branch of mathematics/science which deals with the collection, organization, presentation, analysis and interpretation of numerical data for the purpose of assisting in making a more effective decision. Like almost all fields of study, statistics has two aspects: theoretical and applied. Theoretical or mathematical statistics deals with the development, derivation and proof of statistical theorems, formulas, rules and laws. Applied statistics involves the applications of these theorems, formulas, rules and laws to solve real world problems. 1.3 DIVISIONS OF APPLIED STATISTICS There are two divisions of applied statistics which help decision-makers extract the maximum usefulness from limited information. These areas of applied statistics are descriptive statistics and inferential statistics. DESCRIPTIVE STATISTICS. It is concerned with collecting, organizing, summarizing and presenting data; utilizing techniques to summarize values that describe group characteristics of data. This technique distinguishes the important regularities and patterns of variation from the nonsystematic component of data. The most common values are the measures of central tendency, variation, skewness and kurtosis. Preparation of tables, construction of graphs and computation of measures, such as averages and percentages, fall within this area of statistics. Examples of situations involving the use of descriptive statistics: According to the Human Resource Department of a certain company, the total number of employees is 5,000. The figure 5,000 merely describes the company’s total employment. Thus, the 5,000 is considered descriptive statistics. 2. The guard in a department store records the number of buying customers daily for the past 7 days. 3. The market researcher of a manufacturing company constructs a graph showing the fluctuations in sales for a major product line during the last 3 years. 1. INFERENTIAL STATISTICS. Another facet of statistics is inferential statistics. It is concerned with the predictions and inferences gathered based on pre-selected samples and help make predictions about a population. Selection of a single most desirable course of action from among a set of alternative actions is the concern of this technique. For example, a new product, introduced by a manufacturer, is dependent on the size of the market and its marketing cost. Another example, suppose a company receives a shipment of parts from a manufacturer that are to be used in DVD players manufactured by the company. To check the quality of the whole shipment, the company will select a few items from the shipment, inspect them and make a decision. The area of statistics that deals with such decision in drawing conclusions is referred to as inferential statistics. Examples of situations involving the use of inferential statistics. The manager of a department store records the number of buying customers daily for seven consecutive weeks and then estimates the average number of buying customers for the following weeks. 2. The dean recorded enrolment statistics of the college for the last 6 semesters and then determined if there will be a relative increase or decrease in the enrolment for the next semester. 3. A market researcher wants to find out the relationship of the product cost and the number of products. 4. A market researcher asked a sample of 1,960 consumers to try a newly developed frozen bangus dinner by a Bonoan called Bangus Delight. Out of the 1,960 sampled, 1,176 said they would purchase the dinner if it is marketed. 1. 1.4 BASIC STEPS IN CONDUCTING A STATISTICAL INQUIRY 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. There are basically 5 steps in conducting a statistical investigation. These are: Defining the problem Collecting and organizing relevant information Presenting the data Analyzing the data Interpreting the results 1.5 VARIABLE AND TYPES OF DATA A variable is an observable characteristic or attribute associated with the population or sample being studied which makes one different from the other. It is represented by a set of values that may arise from counting and/or from measurement. It may differ in kind or in degree among various elementary units. A variable may be classified as quantitative or qualitative. 1.5.1 QUANTITATIVE VARIABLES Quantitative variables are variables that are classified according to numerical value. These are expressed numerically because they differ in degree rather than in kind among members of the group. The data collected about a quantitative variable is called quantitative data. Age, height, test scores, weight, prices of cars, number of cars owned, annual income, market sales and stock prices are examples of quantitative variables that can be classified as either discrete or continuous. 1.5.1.1 Discrete Variables Discrete variables can assume values only at specific points on a scale of values with gaps between them. They are obtained by counting and, hence, are countable. Examples of discrete variables are the number of days in a week, the number of children in the family, the number of students in the classroom, the number of teachers in school, the number of house and lots sold on a particular day, the number of people visiting a bank, the number of cars in a parking lot, the number of poultry owned by a farmer and the number of employees of a company. 1.5.1.2 Continuous Variables A continuous variable may take any value within a defined range of values. The possible values of the variable belong to a continuous series. Between any two values of the variable, an indefinitely large number of in-between values may occur. Examples of continuous variables are values obtained by measurement such as weight, height, volume, temperature, distance, area, density, age and price of commodity. 1.5.2 QUALITATIVE OR CATEGORICAL VARIABLES A qualitative or categorical variable is not normally expressed numerically because it differs in kind rather than in degree among elementary units. It is also referred to as attribute variable. This variable can be classified into two or more non-numeric categories according to its characteristics or attributes. The data collected about such a variable are called qualitative data. Data falling under this category cannot be added, subtracted, multiplied or divided. Qualitative variables can be dichotomous or multinomial. Observations about a dichotomous qualitative variable can be made only in two categories; yes or no, defective or non-defective, present or absent, etc. Observations about a multinomial qualitative variable can be made in more than two categories such as educational attainment, nationality, religion, type of colleges and universities, regions, brand of soft drinks, name of companies, occupation, level of job performance, level of job satisfaction, etc. Qualitative data are often summarized in charts and bar graphs. The types of variables are shown in the following diagram: 1.6 PARAMETER AND STATISTICS A parameter is a value or measurement obtained from a population. If one uses the mean, median, mode and standard deviation to differentiate the achievement of one class from another class, he/she uses these measures called parameters. Statistics is any value or measurement obtained from a sample. It is an estimate from the parameter. 1.7 POPULATION AND SAMPLE A population consists of a complete set of individuals, objects, places, items, or events or measurements of interest whose characteristics are being studied. The population that is being studied is called the target population. Like any other set, a population (also known as universe) is classified as either finite or infinite. The distinction is sometimes made between the finite population and infinite population. The children attending school in Butuan City, the percentage of all females who earn less than 100,000.00 a year, the 2007 gross sales of all companies in Metro Manila, the prices of all mathematics books published in the Philippines during the past three years and the cards in a deck are examples of finite populations. The number of such population can presumably be observations in any specific experiments are samples of infinite or indefinitely large population. The number of rolls of a dice or the number of scientific observations may, at least theoretically, be increased without any finite limit. The 92 million or so people living in the Philippines constitute a large but finite population. This population is so large that for many types of statistical inference it may be assumed to be infinite. Because of the large size of the population, it may be either impracticable or impossible for the investigator to gather statistics from all the members. If a population is indefinitely large, it is of course impossible to produce complete population statistics. Under circumstances such as these, the investigator selects what is called a sample. A sample is a portion, or part, of the population selected for study drawn by some appropriate methods from the population. Please note, however, that the method used in drawing the sample from the population is very important. A survey is a collection of information from the elements of a population or a sample. Decisions are based on the sample information. To conduct a survey, we usually select a sample and collect the required information from the elements included in the sample. It is the most common method of generating data not only in business and economics, but also in many other fields. A census is a survey that includes every element of the target population. A sample survey is a technique of collecting information from a portion of the population. The purpose of conducting a sample survey is to make a decision about the corresponding population. The results obtained from the sample survey should closely match with the results obtained in conducting the census. For example, to find the average income of families living in Davao City, the sample must come from all the families having different income groups. This means that the proportions used for the income groupings in the sample must be the same as the groupings in the population. A representative sample represents the characteristics of the population because inferences derived from this sample are more reliable. 1.7.1 REASONS FOR TAKING A SAMPLE Why take a sample instead of studying every member of the population? There are good reasons why surveys are conducted using only a sample from the population. One good reason is that it is not practical or feasible to use the entire population considering factors such as cost, time, staff requirement, difficulty in reaching the respondents, etc. Some of the common reasons for using a sample instead of the population are the following: 1. Some tests are destructive in nature. If wine testers at the La Tondeña Distillery will drink all the wines to evaluate the wine, they will consume the entire stock of wines and none will be available for sale. In the area of industrial production, for instance, steel plates, wires and similar products must often have a certain minimum tensile strength. To ensure that the products meet the minimum standard, a relatively small sample is selected. 2. Considering all the items in the population is impossible. For instance, there is a way we can count the population of fish, birds, snakes, mosquitoes and the like because they are too large and are constantly moving from one place to another, some are born, the others died. Instead of even attempting to count all the ducks in the Philippines or all the fish found in Lake Lanao, we can make estimates using various techniques such as counting all the ducks in a pond picked at random or setting nets at predetermined places in the lake. 3. The cost of studying all the items in a population is often prohibitive. Public opinion polls and consumer testing organizations, such as the Pulse Asia, Social Weather Stations and Ibon Facts and Figures, usually contact fewer than 2,000 persons out of approximately 92 million people in the Philippines. One consumer panel-type organization charges about 1,600,000 to mail out samples and tabulate the responses in order to test a product such as rice variety, dog food or perfume. The same product test using 92 million persons would cost about 9 billion. 4. Sample results are adequate. Even if funds were available, it is doubtful whether the additional accuracy of 100% sample that is, studying the entire population is essential in most problems. Cited for preferring sampling have something to do with reducing the cost of getting a given type of information or with increasing the quality or quantity of information are needed and they can be better trained and more effectively supervised. 1.7.2 SPECIFIC USES OF SAMPLING Taking a sample to find out something about a population is done extensively in business, agriculture, politics, and government. Some examples are the following: Before an election, professional polling organizations such as the Pulse Asia and the Social Weather Stations take a sample of about 2,000 registered voters from the millions of eligible voters. Based on their sample results, general inferences are made regarding how all the voters cast their ballots on election day. Historically, the actual election results have always been remarkably closed to the sample results. 2. The Department of Labor and Employment constantly monitors data on employment, unemployment, salaries, and labor turnover based on sample surveys. 1. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. Television networks regularly monitor the popularity of their programs by hiring the AGB Nielsen and the other organizations to conduct surveys using sample data to find out the preferences of TV viewers. These program ratings are used to determine advertising rates as well as to cancel programs. Marine biologists tag few seals to chart migrating patterns. Wine tasters sip few drops of wine to make a decision with respect to all the wines waiting to be released for sale. The accounting department checks only a few invoices to find out something about the accuracy of all the invoices. Consumers sample pizzas and other products at the grocery store to decide whether to purchase the whole pizza or not. 1.8 SCALES (or LEVELS) OF MEASUREMENT Data can also be classified based on levels of measurements or scales of measurement. There are four levels of measurement used in preparing data for analysis, namely: nominal, ordinal, interval, and ratio level. The nominal level data are of the lowest level, the most primitive or the most limited type of measurement while the ratio levels are classified under the highest level. 1.8.1 NOMINAL SCALE It is a measurement scale that involves the process of naming or labeling the items by placing cases into categories and counting their frequency of occurrences. While the numbers indicate that the elements are different, such difference is not according to order or magnitude. Each case must be placed in one and only one category, but the categories must be equal with respect to some of their attributes or properties. The categories must be non-overlapping or mutually exclusive. There are no measurements and no scales involved. Instead, these are just counts. Examples under nominal scale are gender (male or female), political affiliation (Team Unity, Genuine Opposition, KBL, Lakas CMD, Laban, Kampi, Liberal Party), mode of adaptation (conformity, innovation, ritualism, retreatism, and rebellion), time orientation (past, present, future), religion, region, civil status, names of companies, dichotomous responses or preferences, car makers (Toyota, Honda, Ford, Kia Pride, Hyundai, Volkswagen, BMW). These data are not graded, ranked or scaled for qualities such as better or worse, higher or lower, more or less. They are merely labeled with no meaningful ranking of the categories is applied. This indicates that for the nominal level of measurement, there is no particular order for the groupings. The numbers may not be added, subtracted, multiplied, or divided. Only the frequency and percentage of observations falling into each category are usually computed. While we can also determine the mode under this scale of measurement, we cannot do it for the mean and median. Data under nominal level are often summarized in charts and bar graphs. 1.8.2 ORDINAL SCALE It is a measurement scale that yields information about the ordering of categories. The magnitude of numerical differences between and/or among cases are not determined though. The intervals between the points or ranks in an ordinal level are not known. Therefore, it is not possible to assign scores to cases located at points along the scale. Examples are ranking of honor students, assessment of levels of job performance (poor, average, excellent), ranking of faculty members (instructor, assistant professor, associate professor, professor), hardness of material, IQ (low, average, high), ranking of candidates in a beauty contest, graded response to a certain issue (weak, moderate, strong), rating of a company commander (inferior, poor, average, good, superior) and evaluation of a product (poor, good, excellent). In this scale, one case is said to be greater than or less than the other using a criterion rather than saying that it is only equal or different from the others as what is meant in the nominal scale of measurement. 1.8.3 INTERVAL SCALE It is a measurement scale that shows order of cases into categories considering and indicating the exact differences between and among the cases. It uses constant units of measurement, for example, pesos, centavos, Fahrenheit, Celsius, yards, feet, minutes, seconds, which yield equal intervals between points on the scale. Calendar time is an interval variable with an arbitrary defined zero point. An interval variable does not have a “true zero” point, but a zero point may be arbitrarily defined for convenient purposes only. A temperature of 30 degrees Celsius in Manila cannot be compared to a 15 degrees Celsius in Baguio. It does not make sense, therefore, to talk of a temperature of 0 degrees Celsius indicating the absence of heat or the absence of temperature in a particular place. Scores on a SAT examination and scores in a history or a mathematics examination are also examples of interval scale of measurement. 1.8.4 RATIO SCALE It is a measurement that possesses all the characteristics of interval scale and for which the interval size and the ratio of two values have meanings. In ratio scale, it is appropriate to speak of one number in relation to another. Measurement of weights, heights, lengths and ages appropriately use the ratio scale. Examples of comparisons of measurement such as, a tree 6 meters tall is twice as tall as the other 3-meter-tall tree, a baby girl which weighs 10 lbs. is twice as heavy as a baby girl weighing 5 lbs., could mean that one variable value, or measurement, may be spoken of as double or triple the other variable. An absolute zero is always implied. Any number used represents a distance from a natural origin. One object may be twice as long, three times as heavy or four times as numerous as the other object. The essential difference between the ratio and an interval level variable is that measurements of the former are made from a true zero point, whereas, the latter measurements are from arbitrarily defined zero point of origin. Therefore, the ratio variable is formed directly from the variable values from which meaningful interpretations are done. 1.9 SUMMATION NOTATION The most commonly used notation in statistics is the summation notation which is used to denote the sum of values. The uppercase Greek letter (reads “sigma”) shall be employed to signify that the sum of the values of the variables that follow is desired. Using the notation, we can write the sum as follow: 20 x = x +x + ... + x i i =1 1 2 20