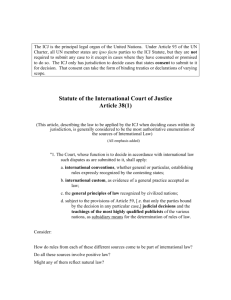

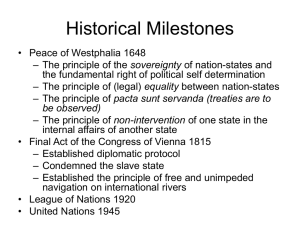

The International Court of Justice (1) Ritsumeikan Asia Pacific University (APU) – College of Asia Pacific Studies AY2025 Spring Semester – International Law: Lecture 11 Shinya Ito 1. General Remarks Located in the Peace Palace (the Hague, the Netherlands). Established in 1945 as “the principal judicial organ of the United Nations” (Article 92 of the UN Charter). The Statute of the International Court of Justice (ICJ Statute). The Statute “forms an integral part of the [UN] Charter” (Article 92 of the UN Charter). All UN members States are ipso facto parties to the Statute (Article 93 of the UN Charter). “Since 1945, in total, 169 contentious cases and 31 advisory proceedings have been filed [to the ICJ]. There are currently 26 cases pending before the Court, involving States from all five regional groups of the United Nations. The Court faces an extraordinarily high workload – a sign of the continuing trust that States place in it.”1 2. ICJ Judges 2.1. The Composition of the Court “The Court shall be composed of a body of independent judges, elected regardless of their nationality from among persons of high moral character, who possess the qualifications required in their respective countries for appointment to the highest judicial offices, or are jurisconsults of recognized competence in international law.” (Article 2 of the ICJ Statute) “The Court shall consist of fifteen Members, no two of whom may be nationals of the same State.” (Article 3 (1) of the ICJ Statute) “The members of the Court shall be elected for nine years and may be re-elected” (Article 13 (1) of the ICJ Statute). 1 ‘Speech of HE Judge Iwasawa Yuji, President of the International Court of Justice, on the Occasion of the Eightieth Anniversary of the Charter of the United Nations’ (26 June 2025) < https://www.icj-cij.org/sites/default/files/press-releases/0/000-20250626-sta-01-00-en.pdf> para. 13. 1 In short, 15 permanent (full-time) judges, elected in their individual capacity (and not as country representatives) for renewable nine-year terms. The ICJ almost always sits as a full Court. Decisions are taken by all judges, emphasising collective deliberation. While the Court ultimately decides by majority, its decisions record votes in favour and against the various operative paragraphs of judgments and advisory opinions. Moreover, judges can express their views in declarations or in separate/dissenting opinions. 2.2. The Election of ICJ Judges Candidates are elected by absolute majorities in both the UN General Assembly and Security Council (Article 10 (1) of the ICJ Statute). “While the [ICJ] Statute emphasizes the individual qualities that are to be looked for in candidates, States are the key actors and without their campaigning, even the best qualified stand no chance of election.”2 Seats must be “the representation of the main forms of civilization and of the principal legal systems of the world should be assured.” (Article 9 of the ICJ Statute) In practice, the allocation of seats informally entails geographical considerations. - Africa (3), Asia-Pacific (3), Western European and Others Group (5), Group of Latin America and Caribbean Countries (2), and Eastern European Group (2). All five permanent members of the UN Security Council traditionally secured seats at the ICJ. However, this is no longer the case in recent years (no British judge since 2017 and no Russian judge since 2023). 3. Contentious Cases The ICJ’s primary task. The Court’s “function … to decide in accordance with international law such disputes as are submitted to it” (Article 38 (1) of the ICJ Statute). When deciding disputes submitted to it, the ICJ facilitates one of the key objectives of the UN – “[t]o maintain international peace and security” (Article 1 (1) of the UN Charter). This aim includes “to bring about by peaceful means, and in conformity with the principles of justice and international law, adjustment or settlement of international disputes” (Article 1 (1) of the UN Charter). 2 Christian Tams, ‘The International Court of Justice’ in Malcolm Evans (ed), International Law (6th edn, Oxford University Press 2024) 555-591, 558. 2 In this respect, “the rule of law [in the international society] is not a static achievement, but a continuous and collective endeavour. The [UN] Charter provides the framework for this pursuit and the Court is instrumental to it.”3 3.1. An Inter-State Court “Only states may be parties in cases before the Court.” (Article 34 (1) of the ICJ Statute) Given the near-universal membership of the UN, the ICJ is presently a court at the disposal of almost all States in the international community. Non-State actors (e.g., individuals, investors, international organizations) do not have standing before the ICJ. They cannot become a party to contentious proceedings. 3.2. The ICJ’s Contentious Jurisdiction 3.2.1. A Court of Potentially General Jurisdiction The ICJ is the only international court of potentially general jurisdiction. The ICJ can address any issues under international law, if States request it to do so. It has no special area of competence (e.g., trade, human rights, sea). 3.2.2. Two Main Ways of Submitting Cases to the ICJ 3.2.2.1. Joint Approaches The traditional mode of establishing the ICJ’s jurisdiction. Parties jointly submit an existing dispute to the Court for it to decide. “The jurisdiction of the Court comprises all cases which the parties refer to it and all matters specially provided for in the Charter of the United Nations or in treaties and conventions in force.” (Article 36 (1) of the ICJ Statute) Such ‘reference’ is typically contained in a special agreement (compromis), which defines the dispute and often outlines the procedure to be followed by the ICJ. 3 ‘Speech of HE Judge Iwasawa Yuji, President of the International Court of Justice, on the Occasion of the Eightieth Anniversary of the Charter of the United Nations’ (26 June 2025) < https://www.icj-cij.org/sites/default/files/press-releases/0/000-20250626-sta-01-00-en.pdf> para. 18. 3 In the case of joint approaches, challenges to the ICJ’s jurisdiction are uncommon. Moreover, parties’ compliance with a judgment rarely becomes a problem. 3.2.2.2. Unilateral Applications Typically, when submitting a unilateral application, the applicant State claims that the respondent State has, in advance, consented to the ICJ’s jurisdiction. (Alternatively, the applicant invites the respondent to give an ad hoc consent to the jurisdiction of the ICJ.) The applicant seeks to rely on the respondent’s pre-existing expression of consent. Such a consent usually covers a generally-defined category of disputes, rather than a particular dispute. The applicant arguably contends that the dispute concerned falls within such a general category. Yet, the respondent may insist that that the dispute falls outside the scope of its expression of advance consent. In such situations, the ICJ must determine whether or not it has jurisdiction over the dispute, and it is competent to interpret the scope of the consent that has been granted. Under Article 36 of the ICJ Statute, it is envisaged that unilateral applications are based on either of the following two types of pre-existing expressions of consent – (i) compromissory clauses or (ii) optional clause declarations. 3.2.2.2.1. Compromissory Clauses “The jurisdiction of the Court comprises all cases which the parties refer to it and all matters specially provided for in the Charter of the United Nations or in treaties and conventions in force.” (Article 36 (1) of the ICJ Statute) E.g., Article IX of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide “Disputes between the Contracting Parties relating to the interpretation, application or fulfilment of the present Convention, including those relating to the responsibility of a State for genocide or for any of the other acts enumerated in article III, shall be submitted to the International Court of Justice at the request of any of the parties to the dispute.” The State’s decision to join a treaty with a compromissory clause is the manner in which it expresses its consent. 4 3.2.2.2.2. Optional Clause Declarations “The states parties to the present Statute may at any time declare that they recognize as compulsory ipso facto and without special agreement, in relation to any other state accepting the same obligation, the jurisdiction of the Court in all legal disputes concerning: a. the interpretation of a treaty; b. any question of international law; c. the existence of any fact which, if established, would constitute a breach of an international obligation; d. the nature or extent of the reparation to be made for the breach of an international obligation.” (Article 36 (2) of the ICJ Statute) E.g., Japan’s Optional Clause Declaration “[I]n conformity with paragraph 2 of Article 36 of the Statute of the International Court of Justice, Japan recognizes as compulsory ipso facto and without special agreement, in relation to any other State accepting the same obligation and on condition of reciprocity, the jurisdiction of the International Court of Justice, over all disputes arising on and after 15 September 1958 with regard to situations or facts subsequent to the same date and being not settled by other means of peaceful settlement. This declaration does not apply to: (1) any dispute which the parties thereto have agreed or shall agree to refer for final and binding decision to arbitration or judicial settlement; (2) any dispute in respect of which any other party to the dispute has accepted the compulsory jurisdiction of the International Court of Justice only in relation to or for the purpose of the dispute; or where the acceptance of the Court's compulsory jurisdiction on behalf of any other party to the dispute was deposited or notified less than twelve months prior to the filing of the application bringing the dispute before the Court; (3) any dispute arising out of, concerning, or relating to research on, or conservation, management or exploitation of, living resources of the sea.” 5 According to Tams, “[w]hereas compromissory clauses are standard features of binding international dispute settlement, optional clauses declarations are peculiar to the ICJ… Devised during the drafting of the PCIJ Statute, they were the substitute for a true system of automatic jurisdiction (which was not considered acceptable at the time, and remains unacceptable). Optional clause declarations enable States to agree, as between themselves, to a system of quasi-compulsory jurisdiction.”4 In practice, however, optional clause declarations often entail reservations. As a result, “[i]nstead of enabling quasi-compulsory litigation between ‘coalitions of willing’, the Court’s jurisdiction under Article 36(2) has become a complex network of bilateral relationships. Unless both acceptances are entirely without reservations (which they rarely are), it is necessary to find the lowest common denominator of the jurisdiction not excluded by the reservations on either side, and then to consider whether the particular dispute falls within it. Unsurprisingly, many cases brought on the basis of optional clause declarations are shaped by lengthy jurisdictional argument and detailed discussion of the effects of reservations.”5 3.3. Discussion In your view, should all States issue optional clause declarations so as to facilitate any dispute being litigated before the ICJ? Why or why not? 3.4. The Handling of Contentious Cases 3.4.1. General Remarks Written pleadings and oral proceedings. Several Steps6 - The finding of facts. - The identification/ascertainment of relevant rules of international law (whether rules exist). - The interpretation of relevant rules of international law (determining the meaning of rules, in particular, clarifying the definition and scope of the treaty term concerned). - The application of relevant rules of international law to the facts (bringing about the consequences of international legal rules to the facts). 4 Christian Tams, ‘The International Court of Justice’ in Malcolm Evans (ed), International Law (6th edn, Oxford University Press 2024) 555-591, 561. 5 Christian Tams, ‘The International Court of Justice’ in Malcolm Evans (ed), International Law (6th edn, Oxford University Press 2024) 555-591, 562. 6 See also Danae Azaria, ‘“Codification by Interpretation”: The International Law Commission as an Interpreter of International Law’ (2020) 31 (1) European Journal of International Law 171-200, 175-177. 6 A quasi-arbitral element in the contentious cases before the ICJ. If a party (applicant/respondent) to a dispute does not have its national on the bench of the ICJ, it can nominate a judge ad hoc for that particular case (Article 31 of the ICJ Statute). 3.4.2. Finding Facts E.g., whether a respondent State acted with genocidal intent, caught whales for the purposes of scientific research (and not eating them as sashimi), etc. The ICJ expects each party to adduce evidence to establish its facts. The Court does not investigate the facts for itself. Essentially, its task is to evaluate such submitted evidence with procedural fairness. Typically, parties present evidence in their written documents, and such evidence is subsequently tested at the oral hearings. In addition to evidence submitted by the parties, the ICJ may also rely on assessments produced by other actors that appear impartial (e.g., UN organs). 3.4.3. Applying International Law As before all judicial bodies, the bulk of an ICJ case is devoted to the application of law to facts (ascertain the meaning of legal rules and to apply them to varied sets of facts). While the ICJ applies all of the sources of international law, most of its work is focused on treaties. A large number of cases are brought on the basis of a treaty clause and are limited to disputes concerning the interpretation and application of that treaty. The ICJ can only address disputes between the parties. A dispute refers to a disagreement on a point of law or fact, or a conflict of legal views or of interests. It is evidenced by prior diplomatic correspondence or statements that reflect an opposition of views on matters within the jurisdiction of the Court. The indispensable third party rule. Even if the ICJ has jurisdiction over a particular dispute, it does not entertain claims that affect interests of a third State which is not party to the proceedings, when those interests form the very subject matter of the proceedings before the Court. 7