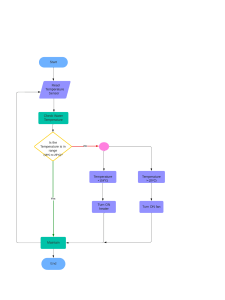

Journal of Global Sport Management 2024, VOL. 9, NO. 3, 545–574 https://doi.org/10.1080/24704067.2022.2155210 A Multi-Method Analysis of Sport Spectator Resistance to Augmented Reality Technology in the Stadium Kim Uhlendorf and Sebastian Uhrich Department of Sport Business Administration, Institute of Sport Economics and Sport Management, German Sport University Cologne, Cologne, Germany ABSTRACT Past research in sports marketing examining technological innovations has predominantly focused on their acceptance by sport spectators. However, theoretical and empirical arguments suggest that investigating innovation resistance provides a distinct and complementary perspective to understanding spectators’ responses to technological innovations. Therefore, the present study examines spectator resistance toward augmented reality (AR) technology used within the stadium. We explore adoption barriers to in-stadium AR, and empirically test their influence on three forms of resistance (postponement, rejection, and opposition). The study used a mixed-method approach comprised of qualitative in-depth interviews (N = 22) and a cross-national online survey (N = 1,206) targeting spectators in Germany and the UK. The study identified seven adoption barriers to in-stadium AR: distraction from the live experience, interference with fan rituals supporting the team, reduced social interactions, reduced emotionality in discussions, risk of personal image damage, fan identity incongruence, and loss of stadium atmosphere. These barriers mainly influenced the resistance forms of rejection and opposition, while the relation to postponement was weaker. Beyond AR technology, this research is the first to examine innovation resistance among sport spectators highlighting the importance to consider downsides of technological innovations and their consequences as well. ARTICLE HISTORY Received 30 March 2022 Revised 1 November 2022 Accepted 15 November 2022 KEYWORDS Innovation resistance; adoption barriers; augmented reality; sport fans; technology 1. Introduction Augmented reality (AR) is an emergent technology that attracts increasing attention from both practitioners and researchers (Wedel et al., 2020). A central promise of AR technology is its ability to enhance consumption experiences by blending the real-world environment with computer-generated elements (Berryman, 2012). Industry reports forecast that the (mobile) AR market will grow to US$13 billion by 2022 and over US$26 by 2025 (Artillery, 2022). Service settings, like museums or art galleries, use AR to create unique experiences for their audience, by integrating the exhibits with digital illustrations or background information. CONTACT Kim Uhlendorf k.uhlendorf@dshs-koeln.de Department of Sport Business Administration, Institute of Sport Economics and Sport Management, German Sport University Cologne, Cologne, Germany. © 2022 Global Alliance of Marketing & Management Associations (GAMMA) 546 K. UHLENDORF AND S. UHRICH AR technology is also increasingly employed in sport consumption settings (Goebert & Greenhalgh, 2020). The prospect of stadia equipped with 5G networks, which enable advanced connectivity and low latency needed for real-time applications like AR, has prompted several professional sport leagues and clubs to incorporate AR directly at the venue to enhance the in-stadium experience of spectators. In stadia, AR features are mostly integrated into existing or new applications for mobile devices, and provide spectators with a virtual extension of the stadium environment by adding digital elements (e.g. live statistics, objects, and graphics). For example, Germany’s premier football league, the Bundesliga, is currently introducing a league app that includes AR-generated real-time statistics to enhance the live game experience (DFL, 2019). Moreover, the US football team Dallas Cowboys recently utilized AR features for in-stadium activations, such as the presentation of a virtual mascot and the opportunity to take pictures with a virtual integration of the team’s players (Forbes, 2019). Given the increasing popularity of this technology in the sport industry, the question arises: how do sport spectators evaluate technological innovations such as AR? Anecdotal evidence suggests ambivalent responses. Market research indicates that spectators are generally inclined to use new technologies in the stadium to increase their enjoyment (Capgemini Research Institute, 2020). However, skepticism has also often accompanied the introduction of new technologies. For instance, market research found that the majority of spectators would refuse the opportunity to use AR applications in the stadium (Facit Digital, 2018). Spectators fear that the technology could harm the traditional stadium atmosphere, and perceive it as part of sports’ undesired commercialization (Forbes, 2020). In the past, spectator resistance even led to innovations being shut off. One example is Fox and the NHL’s innovation FoxTrax, a puck tracking system that highlights the puck, enabling better visibility of it. The innovation was heavily criticized by spectators for being distracting and inauthentic (The Wall Street Journal, 2016). To anticipate and avoid such undesired responses to technological innovations, sport properties need to have a detailed understanding of the antecedents of spectator resistance and the manifestations of this behavior. However, despite the frequent problems with introducing technological innovations, past research has largely overlooked spectator resistance and its drivers. The extant work focused on positive innovation characteristics and analyzed the drivers of adoption decisions, mainly utilizing the technology acceptance model (e.g. Kang, 2014; Kim et al., 2017). One exception is Uhrich’s (2022) work on fan experience apps. This study distinguished between reasons for and reasons against adopting innovations and showed that both factors independently influence adoption behavior. While the study makes an important contribution in differentiating drivers and barriers of adoption, it does not consider spectator resistance as a unique outcome variable. However, doing so is important as research shows that resistance and non-adoption should be considered as distinct concepts (Kleijnen et al., 2009). That is because resistance refers to different behavioral facets that go beyond simply not using an innovation. For example, non-adopters may generally like an innovation, but still not use it at this point because they perceive it as not sufficiently developed. However, other non-adopters may be strongly opposed to the innovation and show Journal of Global Sport Management 547 adversarial behaviors like spreading negative word-of-mouth or engaging in protests (Szmigin & Foxall, 1998). Seeing such different behavioral reactions simply as the opposite of adoption with not further differentiation impedes a nuanced understanding of negative spectator responses to technological innovations. Against this background, this study makes the following contributions: First, we explore adoption barriers related to AR technology in the stadium using in-depth interviews with spectators from different sports. This qualitative exploration reveals key factors leading to AR technology resistance and, hence, extends previous literature that investigates factors for AR adoption in the sport spectator setting (Goebert & Greenhalgh, 2020; Rogers et al., 2017). The exploration of such barriers is important, because besides pro-adoption factors, innovation-specific barriers may exist which drive spectator resistance (Uhrich, 2022; Winand et al., 2021). Such barriers must be analyzed in addition to adoption drivers, because they are often not simply the opposite of those factors that cause acceptance or non-acceptance of an innovation (Heidenreich & Spieth, 2013; Kleijnen et al., 2009). For example, people may appreciate the advantages of an innovation, but still not adopt it because of cost or image barriers. Second, we use quantitative data to validate and empirically link the adoption barriers to spectator resistance. The quantitative study confirms that all factors identified in the qualitative phase are significant reflections of why spectators resist AR. Further, we test and confirm the generalizability of the results across several important fan segmentation variables (i.e. fan identification, season ticket ownership, favorite sport) as well as two different nations (UK and Germany). Third, our study is the first to address the concept of innovation resistance as a dependent variable in the sport marketing literature, hence, identifying a novel category of sport spectator responses to technological innovations. Drawing on existing innovation resistance theory (Kleijnen et al., 2009), we conceptualize sport spectator resistance in terms of three dimensions: postponement, rejection, and opposition. This is important because sport spectators often publicly voice their concerns, and engage in active rebellion when they are dissatisfied with managerial decisions (Merkel, 2012). Thus, an in-depth understanding of spectator resistance is particularly important for sport properties. Knowledge of the drivers of spectator resistance is a prerequisite for sport managers to take effective countermeasures before introducing the innovation. 2. Theoretical Background and Literature Review 2.1. Defining and Conceptualizing Innovation Resistance The innovation management literature broadly defines consumer resistance to innovations as a form of negative attitude toward new products and services that trigger change or conflict within the status quo (Ram & Sheth, 1989; Szmigin & Foxall, 1998). A growing stream of literature in this field (e.g. Gatignon & Robertson, 1989; Kleijnen et al., 2009; Szmigin & Foxall, 1998) stresses the importance of distinguishing between innovation adoption and innovation resistance as these are distinct concepts and innovation resistance ‘is not the mirror image of adoption, but a 548 K. UHLENDORF AND S. UHRICH different form of behavior’ (Gatignon & Robertson, 1989, p. 47). Thus, innovation resistance must be examined separately from, or in addition to, innovation adoption to account for these distinct underlying behavioral patterns (e.g. Kleijnen et al., 2009). Thus, the rationale for this distinction is twofold. First, there are often unique factors driving consumers’ decisions to reject an innovation (Ram & Sheth, 1989). This means that in addition to adoption drivers, such as perceived usefulness or entertainment (Davis, 1989), distinct factors may exist that cause resistance to innovations (Claudy et al., 2015; Ram & Sheth, 1989). These factors are referred to as adoption barriers, namely, they are factors that ‘paralyze the desire to adopt innovations’ (Ram & Sheth, 1989, p. 7). Knowledge of the adoption barriers relating to a specific innovation is important because consideration of them alone is often insufficient to explain consumers’ responses to innovations. The second reason why resistance must be distinguished from adoption is that resistance is more than simply non-adoption. Innovation resistance is a broad concept that embraces different attitudinal and behavioral patterns different from acceptance behaviors (Kleijnen et al., 2009; Szmigin & Foxall, 1998). Thus, adoption barriers can influence consumers’ decisions in different ways than adoption drivers (Gatignon & Robertson, 1989). As a result, resistance cannot simply be captured by non-adoption behavior or not-trying an innovation (e.g. Gatignon & Robertson, 1989; Kleijnen et al., 2009). It is a multi-faceted phenomenon that can embrace different and very distinct behaviors (Kleijnen et al., 2009). For example, opposing an innovation by spreading negative word-of-mouth is not the same as non-adoption, in the sense of not-trying it. There are behavioral patterns underlying resistance, which cannot be captured when considering it as the opposite of adoption. Based this notion, Kleijnen et al. (2009) define three specific dimensions of innovation resistance embracing different behavioral patterns, namely postponement, rejection and opposition. Postponement is a temporal form of resistance where consumers consider an innovation acceptable in principle, but decide not to adopt it until the circumstances are more suitable. For example, sport spectators can be initially reluctant to adopt AR in the stadium because they may be uncertain as to whether using the technology is compatible with the group consumption norms. This barrier can be overcome at a later stage if others’ use of AR signals acceptance of the social environment. However, spectators can also exhibit a lasting negative attitude toward AR, resulting in the deliberate decision to refuse it, regardless of its further development. This is a stronger form of resistance, which is referred to as rejection. Rejection implies an active evaluation on the part of the consumer, resulting in a strong reluctance to accept the innovation (Kleijnen et al., 2009). The main difference to postponement is that spectators rejecting AR are unlikely to be convinced of its use, by changes regarding its features or other circumstance, as their attitude toward the technology is relatively persistent over time. In addition, since many sport spectators are highly identified with their role as fans and emotionally connected with their favorite club, they tend to be actively opposed to what they perceive as undesired interventions in their consumption habits (Merkel, 2012). Journal of Global Sport Management 549 Thus, another relevant manifestation of resistance includes active rebellion and boycotts of AR. This is the strongest form of resistance and is labeled opposition (Kleijnen et al., 2009). In the case of opposition, consumers are convinced that the innovation is unsuitable, and decide to take action against its introduction or presence on the market. In contrast to rejection, which refers to passive refusal, opposition means that consumers actively express their dissatisfaction with the respective innovation. Although this three-dimensional conceptualization allows a fine-grained analysis of innovation resistance and highlights its distinct characteristics compared to acceptance, the majority of empirical research does not distinguish between different manifestations of the construct (e.g. Antioco & Kleijnen, 2010; Kuisma et al., 2007; Laukkanen et al., 2007). This is a shortcoming because it is unlikely that adoption barriers influence all facets of resistance to the same extent. 2.2. Adoption Barriers Research in the field of innovation resistance has proposed several models defining adoption barriers for technological innovations. The majority of studies draw on the established model by Ram and Sheth (1989), which suggests five general adoption barriers relating to technological innovations (i.e. usage, value, risk, tradition, and image barrier). These are further divided into functional and psychological barriers. Functional barriers relate to usage patterns, the perceived value and risks associated with using a new product or service. These barriers emerge when consumers perceive that the adoption of an innovation leads to significant changes in these areas. Psychological barriers arise when the innovation is in conflict with consumers’ prior beliefs. These beliefs relate to traditions and norms, as well as to the image of an innovation. As a result of its broad applicability, Ram and Sheth’s (1989) conceptualization is widely used to explain resistance toward technological innovations across various contexts (e.g. Antioco & Kleijnen, 2010; Kuisma et al., 2007; Laukkanen, 2016; Laukkanen et al., 2007). However, as with any higher-level theory, this broad conceptualization is somewhat limited in explaining consumer resistance to specific innovations like AR technology. Simply transferring these general adoption barriers to AR might result in neglecting the innovations’ unique characteristics, and leave specific factors driving resistance undisclosed. With this limitation in mind, several studies explore innovation-specific barriers, for instance, in relation to Internet of Things devices (Mani & Chouk, 2018) or autonomous vehicles (Casidy et al., 2021). This research highlights the importance of studying specific innovations because consumer resistance is often driven by unique barriers. For example, Claudy et al. (2015) find that availability is an important barrier in the context of car-sharing services; De Bellis and Johar (2020) identify the barrier of reduced social connectedness for autonomous shopping systems; and Mani and Chouk (2018) show that resistance to Internet of Things devices is driven by self-image incongruence. However, research on resistance to in-stadium innovations is almost non-existent. An exception is Uhrich’s (2022) exploration of drivers and barriers of fan experience 550 K. UHLENDORF AND S. UHRICH app adoption. The study identifies several reasons against using such apps in the stadium, including distraction from the game, negative impact on the atmosphere, security concerns, and social risk. While this study provides an initial insight into innovation adoption barriers that may also be relevant for AR technology, it does not examine how such barriers influence spectator resistance. In addition, since adoption barriers are context-specific, different barriers might exist for the distinct technology of AR compared to fan experience apps in general. Further, studies have found that reduced opportunities for emotional debates are a reason for spectators to reject video assistant referee technology in stadia (Winand et al., 2021; Winand & Fergusson, 2018). Forslund (2017) notes that technological innovations conflicting with long-established traditions and social consumption norms of the sport consumption context are likely to face resistance from spectators. For in-stadium AR technology, only adoption drivers, such as perceived usefulness, have been examined (e.g. Goebert & Greenhalgh, 2020). In general, consumer evaluations relating to AR are still largely unexplored (Wedel et al., 2020). In the broader marketing context, AR is mostly studied in retail settings (e.g. Tan et al., 2022), or the e-commerce sector and here especially for product experiences (e.g. Hilken et al., 2017). This research centers on pro-adoption factors of this technology (e.g. Castillo & Bigne, 2021), a shortcoming that has recently been pointed out as consumers can encounter several distinct challenges when using AR, for instance, privacy concerns (Cowan et al., 2021; Wedel et al., 2020). Thus, adoption barriers inhibiting the introduction of AR technology, in particular in the sport consumption context, are yet to be examined. In view of these research gaps, we set out to explore adoption barriers to AR technology in the stadium. To achieve this, we conducted a qualitative study that is presented in the next section. 3. Study 1: Exploration of AR Adoption Barriers 3.1. Method As the paper is the first to focus on spectator resistance, a qualitative study intended to explore barriers driving resistance toward AR technology in the stadium from the perspective of sport spectators. To this end, we conducted semi-structured in-depth interviews with team sport spectators (N = 22). 3.1.1. Study Context, Participants, and Procedure Professional team sport leagues in Germany served as the empirical setting for the study. AR technology is currently being widely discussed among German clubs and leagues. The football league Bundesliga recently initiated tests to introduce the technology in stadia (DFL, 2019). Given that AR is predominantly integrated into mobile apps (eMarketer 2020), we focus on smartphone-based AR in our analyses. The sampling procedure consisted of two steps. We initially defined general criteria participants must meet to be eligible as interview partners. For example, they had to be a fan of a professional sports team and regularly attend live games in the stadium. Moreover, fans of one of Germany’s four most popular team sports in Journal of Global Sport Management 551 Table 1. Participants of Study 1 and their characteristics. Participant Age Gender Sport Fan category Attendance frequency Season Preferred (homes games) ticket ticket category Jonathan 23 m Soccer Active fan 25-49% Yes Standing area Mario 24 m Soccer Active fan 50-74% No Standing area Sophie 24 f Soccer Fan 25-49% No Seating area Henning 67 m Soccer Casual supporter 75-100% Yes Seating area Lennart 23 m Soccer Active fan 50-74% No Seating area Joscha 22 m Soccer Active fan 75-100% Yes Seating area Achim 66 m Soccer Active fan 0-24% Yes Seating area Conny 57 f Soccer Active fan 0-24% Yes Seating area Lara 25 f Soccer Casual supporter 0-24% No Standing area Peter 58 m Soccer Fan 0-24% No Seating area Josi 24 f Handball Fan 0-24% No Seating area Mirco 38 m Soccer Fan 75-100% Yes Standing area Volker 69 m Ice Hockey Fan 75-100% Yes Both Helena 23 f Handball Fan 0-24% No Seating area Angelika 61 f Handball Fan 75-100% Yes Seating area Basti 27 m Ice Hockey Fan 0-24% No Seating area Bene 32 m Basketball Casual supporter 0-24% No Both Anton 23 m Ice Hockey Active fan 50-74% No Both Bjarne 24 m Basketball Fan 25-49% No Both Florian 25 m Ice Hockey Fan 75-100% Yes Seating area Uwe 56 m Basketball Fan 25-49% No Standing area Florian R. 32 m Ice Hockey Fan 25-49% Yes Seating area Notes: Fan categories are defined as follows: Casual supporter = sympathizes with a team; Fan = regular fan, but not a member of a supporters’ club; Active Fan = engaged fan who is a member of a supporters’ club. terms of attendance (i.e. soccer, ice hockey, handball, basketball) were eligible to participate in the study (Presseportal, 2017). As the data collection progressed, we applied theoretical sampling because the selection of participants became more purposive (Charmaz, 2006; Fischer & Guzel, 2022). We targeted spectators who varied in attendance frequency, season ticket ownership, preferred ticket category, fan category, and gender and age to represent different spectator segments. The consideration of these potentially conceptually relevant variables served the purpose to develop a comprehensive classification of drivers of in-stadium AR technology resistance. Participants were recruited via personal contacts. A short questionnaire covered the demographics of the participants and assessed the selection criteria before the interviews. All participants had at least basic knowledge of AR technology and were given detailed explanations about its application in the stadium context by the interviewer. Table 1 displays the characteristics of the informants. We developed an interview guide based on the recommendations given by Creswell (2013) that addressed five major topics (see Appendix A). The first section included an introduction to the topic, a detailed definition of AR technology and its applications in the stadium context as well as explanations concerning the interview process. Second, photo-elicitation was used to familiarize participants with the technology again and further assess participants’ general thoughts about the technology. Afterwards, they were asked about potential problems regarding this technology. Specifically, respondents replied to questions such as what factors would prevent them from using AR technology, and what difficulties they would encounter when using it in the stadium. Next, the informants were asked to report situations in the stadium and during the game in which they would experience AR as disturbing. Fourth, a set of questions dealt with the social component of the stadium 552 K. UHLENDORF AND S. UHRICH visit. For example, informants were asked to what extent friends and other fans might play a role in their decision to use AR. Finally, the perceived image of the technology was addressed by asking respondents what kind of people they imagined would use AR technology and what might differentiate these individuals from themselves. To conclude the interviews, the interviewer provided a summary of the answers and respondents were asked to confirm that their view had not been misinterpreted. Initially, test interviews were conducted to refine the interview guide and check the technical requirements. The interviews lasted between 25 and 45 minutes and were conducted either as video calls or face to face. Participants filled out a consent form to approve the recording of their interviews. When theoretical saturation was reached no further interviews were conducted (Charmaz, 2006). All interviews were transcribed verbatim, resulting in 212 pages of text with 1.5 line spacing. The average number of words per interviews was 4,217 (ranging from 2,828 to 6,900 words). 3.1.2. Analysis The qualitative analysis followed the steps suggested by Creswell (2013), and used the software package MAXQDA to process the text material. We read through all transcripts to get an overview of the data, and a general sense of the information contained in them. Next, a mix of deductive and inductive coding was used to identify categories of possible barriers. Existing conceptualizations of technology resistance barriers (e.g. Ram & Sheth, 1989) provided initial guidance for broad categories, such as usage or image barriers. Inductive coding was then predominant when establishing specific barriers of in-stadium AR technology resistance. For this purpose, we developed a codebook with coding rules to establish the respective categories. These categories were then described in more detail, and distinct barriers toward AR were generated. Finally, the findings’ meaning was interpreted and put into the context of previous literature. We followed previous work (e.g. Mani & Chouk, 2018), and juxtaposed the identified barriers of adopting AR technology in the stadium with barriers included in Ram and Sheth’s (1989) conceptualization. This was done to explore whether our findings indicated specifics and notable differences (e.g. new categories of adoption barriers) compared to the Ram and Sheth (1989) model. Thus, the theory was tested and refined regarding its application to the context of in-stadium AR. To establish validity, the findings were constantly compared and discussed among the authors. 3.2. Results The data analysis yielded seven barriers driving resistance toward smartphone-based AR in the stadium. Figure 1 displays the seven barriers and their categorization according to the Ram and Sheth (1989) model. Further, Table B1 in Appendix B presents a full overview of the barriers’ definitions, exemplary quotes, and their relation to Ram and Sheth’s (1989) barriers. In line with Uhrich’s (2022) finding for app usage, the first barrier to using AR refers to concerns about being distracted from the game and the live experience, Journal of Global Sport Management 553 Figure 1. Model of in-stadium AR technology resistance juxtaposed against Ram and Sheth’s (1989) classification of adoption barriers. labeled distraction from the live experience. AR causes sport spectators to move their focus away from the game and toward the technology. However, fully focusing on the live action on and off the pitch is considered a core activity by most spectators. Using AR technology strongly conflicts with this activity and, therefore, this aspect represents a key barrier driving resistance. Using AR also interferes with established fan rituals performed during the game in support of the fans’ own team (e.g. singing, clapping, shouting). Thus, the second barrier is called interference with fan rituals supporting the team. AR negatively affects—or even completely prevents—fans’ engagement in such rituals. Since fan rituals can be a crucial element of the stadium experience, spectators are reluctant to change or even give up such rituals to use AR. The barrier of reduced social interactions reflects the fear of having reduced interactions with other fans in the stadium through the use of AR technology. Since using the innovation requires spectators’ full attention, they would not be able to interact with others during this time. Interacting with the people around them is important to spectators and, hence, they are not willing to reduce such behavior. Next, the barrier reduced emotionality in discussions refers to the fear that the information provided by AR technology, specifically live statistics and data about the match, reduces heated discussions among spectators. Engaging in emotionally charged conversations with others is a desirable activity in stadia. Spectators are concerned that the character of such discussions would shift from being emotional 554 K. UHLENDORF AND S. UHRICH and speculative to data-based objectivity. This would decrease spectators’ enjoyment of the stadium visit. This is in line with Winand et al.’s (2021) finding that sport spectators are dissatisfied with video assistant refereeing technology because it inhibits controversial discussions. The barrier risk of personal image damage is related to the social component of the stadium setting. Fans were concerned that they would be perceived as rude or disrespectful when they disturbed others in their experience of the game through AR usage. Additionally, they feared direct criticism like unfriendly comments from friends and other relevant people around them. Next, the barrier loss of stadium atmosphere refers to spectators’ fear of losing the traditional atmosphere in the stadium. This could be the case if fans were to replace cheering for their team by excessive use of AR technology in the stands. This barrier is consistent with Uhrich’s (2022) finding that concerns about a decline in stadium atmosphere is a reason against using in-stadium apps during games. Lastly, fan identity incongruence describes spectators’ perception that their own values and beliefs about sport fandom are inconsistent with the image of using AR. Using this technology in the stadium is seen as a component of undesired commercialization processes, which change the way spectators consume sport. This stands in contrast to many spectators’ identity. Thus, respondents feel a distance between themselves and the prototypical user of in-stadium AR technology, which is seen as inauthentic fan behavior. This barrier is similar to Mani and Chouk’s (2018) self-image incongruence barrier, which refers to the perceived incompatibility between the consumer’s self-image and the image of the innovation and/or the image of the innovation’s typical users. 3.3. Discussion of Study 1 Study 1 identifies seven barriers that can cause sport spectators to resist using AR in the stadium. The findings confirm the theoretical notion that adoption barriers must be distinguished from adoption drivers because the identified barriers represent distinct aspects that are not simply the opposite of adoption drivers. Thus, the barriers can co-occur with factors that drive AR adoption (e.g. perceived fun). While the seven barriers are unique aspects leading to resistance to in-stadium AR adoption, they can be assigned to the higher-level barriers included in Ram and Sheth’s (1989) general classification, as displayed in Figure 1. Thus, our study offers a context-specific version of this broader theory. However, it is still unclear if, and to what extent, these barriers influence spectator resistance. Studies 2 and 3 address this issue by analyzing the relationships between the barriers and the three suggested manifestations of resistance based on quantitative data. 4. Study 2: Assessment of Measurement Properties Study 2 aimed to evaluate the measurement properties of the self-developed scales for the seven adoption barriers. The study employed two consecutive surveys as Journal of Global Sport Management 555 pretests targeting team sport spectators who regularly attend the stadium. We chose to conduct two surveys in order to increase the generalizability of the measurement properties using two different samples. 4.1. Method 4.1.1. Item Development Measures for the adoption barriers were developed based on the text material of the exploratory study. To achieve content validity, the item generation was closely linked to the definitions of the constructs, as established in Study 1. In addition, expressions and statements from the interview participants were considered to develop items that match the wording of the targeted population. A few participants of the qualitative study were contacted again, and the measures of all constructs, as well as their overall definitions, were presented to them. The participants were asked to state if the items represented the respective constructs clearly and unambiguously. The majority of respondents confirmed the items as good reflections of the constructs and only small adjustment were made. Further refinements were made to the item formulations based on the results of Study 2. Table 4 presents the final items used in the main study. 4.1.2. Data Collection and Analysis As in the qualitative study, we used the four most popular team sport leagues in Germany as our empirical setting. Data were collected via an online survey using a convenience sampling approach for both samples. The links to the respective surveys were spread via social media channels of team sport clubs and leagues, as well as by online discussion boards and supporters’ clubs. Regular stadium visitors were identified using a pre-screening question asking respondents to indicate whether they attended live games in the stadium from time to time. To ensure that participants were familiar with AR technology and its usage in the stadium, the first part of the survey included an explanation of the technology, its characteristics and specific features for in-stadium use. Pictures of sport spectators using the technology complemented the text-based explanations. Respondents were excluded if they did not pass the attention checks included in the study (e.g. tick ‘2′ and go to the next question) and/or finished the questionnaire after a break. Survey 1 was run in March 2021, resulting in 280 valid responses, and Survey 2 in April 2021, resulting in 286 valid responses. Both samples included predominantly male respondents (Survey 1: 74.6% male; Survey 2: 85.0% male) with an average age of 37.1 years (SD = 14.53) and 29.5 years (SD = 10.85), respectively. The respondents were mainly fans of soccer teams (Survey 1: 72.9%; Survey 2: 92.7%). Confirmatory factor analyses using SPSS AMOS (version 27) tested the measurement properties of the seven adoption barriers. 4.2. Results and Discussion of Study 2 The scales for all adoption barriers were tested regarding their internal consistency by assessing Cronbach’s alpha. In both surveys, the values for Cronbach’s alpha 556 K. UHLENDORF AND S. UHRICH Table 2. CFA results and construct descriptives for Study 2 (both surveys). Ma SD #Items CR AVE 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 1. Interference with fan rituals supporting the team Survey 1 4.58 1.83 .88 2 0.88 0.79 0.89 Survey 2 3.63 1.29 .90 2 0.90 0.82 0.91 2. Distraction from the live experience Survey 1 5.23 1.62 .94 3 0.95 0.85 0.77 0.92 Survey 2 3.96 0.97 .90 3 0.90 0.75 0.75 0.86 3. Reduced social interactions Survey 1 4.77 1.87 .93 3 0.93 0.82 0.83 0.79 0.90 Survey 2 3.81 1.10 .90 3 0.90 0.75 0.80 0.80 0.86 4. Reduced emotionality in discussions Survey 1 4.42 1.46 .81 3 0.80 0.58 0.70 0.59 0.68 0.76 Survey 2 3.40 1.02 .79 3 0.78 0.55 0.56 0.59 0.66 0.74 5. Risk of personal image damage Survey 1 3.88 1.56 .92 6 0.92 0.67 0.70 0.57 0.67 0.48 0.82 Survey 2 3.23 1.08 .90 5 0.90 0.64 0.73 0.60 0.66 0.51 0.80 6. Fan Identity Incongruence Survey 1 4.51 1.57 .90 5 0.90 0.63 0.76 0.70 0.79 0.65 0.68 0.80 Survey 2 3.36 1.09 .85 4 0.86 0.61 0.80 0.78 0.82 0.64 0.75 0.78 7. Loss of stadium atmosphere Survey 1 4.70 1.80 .94 3 0.94 0.83 0.81 0.76 0.83 0.68 0.66 0.87 0.91 Survey 2 3.64 1.14 .92 3 0.92 0.79 0.81 0.82 0.84 0.63 0.70 0.90 0.89 Note: all correlations were significant (p < .001). a the seven barriers were measured on a seven-point rating scale in Survey 1 and a five-point rating scale in Survey 2. indicated good reliability for all barriers, ranging from .79 to .94. Table 2 displays the mean values, standard deviations, number of items, and Cronbach’s alpha of all constructs for both surveys. Regarding the remaining measurement properties, results indicate a good overall fit for both the model of Survey 1 (χ2 = 533.982, df = 254, p < .001; χ2/df = 2.18; RMSEA = 0.065; CFI = 0.95; SRMR = 0.036; TLI = 0.95) and the model of Survey 2 (χ2 = 410.321, df = 209, p < .001; χ2/df = 1.96; RMSEA = 0.058; CFI = 0.96; SRMR = 0.039; TLI = 0.95). All factor loadings were highly significant (p < .001) and above the cut-off criterion of 0.5. Further, all seven barriers indicated high reliability and convergent validity as the values for construct reliability and average variance extracted (AVE) exceed the recommended thresholds of 0.7 and 0.5, respectively (Bagozzi & Yi, 2012). Moreover, for all but one scale, the square root of the AVE was higher than the highest correlation with any other construct, supporting discriminant validity (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). The exception is the correlation between loss of stadium atmosphere and fan identity incongruence, which was slightly higher than the square root of the AVE for fan identity incongruence in both surveys. However, as all other measurement properties were satisfactory for these constructs, they remain in the subsequent analyses. Table 2 displays the results of the respective CFAs in more detail. 5. Study 3: Test of Structural Model The goal of Study 3 was to test the relationships between the adoption barriers and the three manifestations of resistance (postponement, rejection, opposition). Journal of Global Sport Management 557 5.1. Method 5.1.1. Study Context, Data Collection, and Participants For Study 3, we recruited team sport fans from two countries, namely Germany and the UK. The cross-national sample aimed to increase the generalizability of our findings. Like the German team sport industry, AR also proliferates in the UK, and has been introduced by several professional clubs (e.g. Arsenal FC, Manchester City, Tottenham Hotspur). Further, the total attendance-per-capita of professional live sports is among the highest worldwide (Two Circles, 2019). Thus, the UK market provides an appropriate setting for our study. The data were collected from 10 to 30 June, 2021, using online surveys. We applied quota sampling (age, gender, favorite team sport) to match our sample with the characteristics of team sport spectators in Germany and the UK, respectively. UK respondents were recruited via the online panel provider Talk Online Panel, while German participants were recruited by research assistants who distributed the link to the survey among potential participants using social media channels, as well as emails. In order to meet the quotas in Germany, we regularly checked the data, and implemented pre-screening questions that ensured fulfillment of the criteria. We included soccer, ice hockey, basketball, and handball spectators from Germany as well as soccer, rugby, cricket, and ice hockey spectators from the UK because these sports are the most popular live sports in terms of attendance figures in their respective countries (Presseportal, 2017; Two Circles, 2018). The quotas for age and gender were selected based on several sources, including previous surveys and statistics on sport spectators in the two countries (e.g. EFL Report, 2019). The data collection yielded 503 valid responses from the UK and 703 valid responses from Germany with both samples fulfilling the targeted quotas (see Table 3). As detailed in the preregistration,1 two initial screening questions filtered out respondents who never attended live games at the stadium or who did not have German or British citizenship, respectively. Further, participants were eliminated if they did not pass the three attention checks (e.g. tick ‘6′ and go to the next question) and/or finished the questionnaire after a break. The preregistration included all details regarding the research questions, methods, measures, and exclusion criteria. 5.1.2. Measures and Analysis The dependent variables postponement (3 items [Kleijnen et al., 2009]; α = .61), rejection (3 items [Mani & Chouk, 2018]; α = .93), and opposition (3 items [Kleijnen et al., 2009]; α = .92) were measured using a seven-point rating scale (1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree). Further, we included innovativeness, age, gender, and knowledge about AR as control variables, as previous studies show that these constructs predict innovation resistance (e.g. Laukkanen et al., 2007; Szmigin & Foxall, 1998). The scale for innovativeness (3 items, α = .88) stems from Kim et al. (2017), and the measures of knowledge about AR (3 items, α = .91) were adapted from Bang et al. (2000), both using the above mentioned seven-point rating scale. Table 4 displays the items, Cronbach’s alpha, means, and standard deviations for all constructs used in the main study. 558 K. UHLENDORF AND S. UHRICH Table 3. Sample characteristics of Study 3. UK (n = 503) n % Germany (n = 703) Quotas 1 n Gender Male 424 84.3% 85% 486 Female 79 15.7% 15% 211 Othera – – 6 Age 16-24 53 10.5% 10% 253 25-34 105 20.9% 20% 198 35-44 104 20.7% 20% 88 45-54 131 26.0% 25% 88 55-64 78 15.5% 15% 68 > 65 32 6.4% 10% 8 Education No degree 96 19.1% 2 Certificate of secondary educationa – – 108 A-Level 170 33.8% 282 University degree 208 41.1% 293 Doctoral degree 29 5.8% 18 Favorite team sport Soccer 433 86.1% 85% 491 Rugby (Ice Hockey)b 42 8.3% 9% 121 Cricket (Handball)b 19 3.8% 4% 49 Ice hockey (Basketball)b 9 1.8% 2% 42 Fan group membership Active fan (member in a 118 23.5% 91 supporter’s club) Fan (not a member in a supporter’s 289 57.5% 444 club) Casual fan/supporter 96 19.1% 168 Season ticket holder Yes 115 22.9% 185 No 388 77.1% 518 Attendance frequency (home games) 0-24% 261 51.9% 353 25-49% 84 16.7% 104 50-74% 73 14.5% 61 75-100% 85 16.9% 185 Previous usage of AR applications Yes 163 32.4% 280 No 340 67.6% 423 Frequency of previous used AR applications 1 to 4 times 91 55.8% 130 5 to 9 times 31 19.0% 73 10 to 14 times 19 11.7% 33 15 to 19 times 11 6.7% 11 20 times and more 11 6.7% 33 a only queried in German questionnaire. b Sports for the German sample are displayed in brackets. 1 References: Two Circles, 2018; EFL Report, 2019; FSA National Supporters Survey, 2017. 2 References: Grau et al., 2016; Ziesmann et al., 2017. % Quotas2 69.1% 30.0% 0.9% 75% 25% 36.0% 28.2% 12.5% 12.5% 9.7% 1.1% 35% 25% 15% 10% 10% 5% 0.3% 15.4% 40.1% 41.7% 2.6% 69.8% 17.2% 7.0% 6.0% 75% 10% 10% 5% 12.9% 63.2% 23.9% 26.3% 73.7% 50.2% 14.8% 8.7% 26.3% 39.8% 60.2% 46.4% 26.1% 11.8% 3.9% 11.8% Regarding the analyses, we first tested for measurement invariance before collapsing the samples from the two different countries for further analyses, following the steps suggested by Cheung and Rensvold (2002) and Chen (2007) for large sample sizes. We also relied on their recommended thresholds for the goodness-offit indices (i.e. CFI, RMSEA, and SRMR). First, we conducted a CFA separately with all focal measures of the study for both countries (Models 1 and 2 in Table 5) to test configural invariance. Second, metric invariance was tested by running a CFA Journal of Global Sport Management 559 Table 4. Constructs and items used in Study 3, mean values, standard deviation, and Cronbach’s alpha. Construct Distraction from the live experience Interference with fan rituals supporting the team Reduced emotionality in discussions Reduced social interactions Risk of personal image damage Fan identity incongruence Loss of stadium atmosphere Items Mean SD Cronbach’s alpha The use of AR technology during the game distracts me from the game and the stadium environment ( e.g. fan actions within the stands). The use of AR technology during the game leads to missing something important from the game. The use of AR technology during the game prevents me from focusing on the game highlights and the stadium environment. The usage of AR technology during the match will hinder me from cheering for my team within the stadium ( e.g. singing, clapping, waving scarves). The usage of AR technology during the match will prevent me from supporting my team. The facts, data, and statistics presented by AR technology reduce emotional discussions with other fans and friends. The facts, data, and statistics presented by AR technology lead to data-driven rather than emotional discussions. The facts, data, and statistics presented by AR technology reduce joint debates about controversial match decisions. The use of AR technology during the game means that I interact less with other fans/ friends in the stadium. The use of AR technology during the game means that I cheer less with other fans/ friends around me. The use of AR technology during the game means that visiting the stadium becomes more impersonal. If I used AR technology during the game other fans would think badly of me because I disturb their game experience. If I used AR technology during the game other fans would think of me as being rude/ disrespectful because I obstruct their view. If I used AR technology during the game my friends/other fans in the stadium would not perceive it well. If I used AR technology during the game, I would fear negative feedback from other fans. Fans who use AR technology are different fans than I am. AR technology is something for casual spectators, but not for me. I do not identify with the typical user of AR technology. AR technology represent a part of the commercialization which I reject. When using AR technology during the game the stadium atmosphere gets lost. When using AR technology during the game the stadium atmosphere changes for the worse. When using AR technology during the game the stadium and fan culture suffers. 3.71 1.13 .93 3.38 1.23 .83 3.42 1.02 .84 3.62 1.11 .89 3.13 1.11 .89 3.15 1.10 .89 3.50 1.02 .93 (Continued) 560 K. UHLENDORF AND S. UHRICH Table 4. Continued Construct Postponement Rejection Opposition Items Mean SD Cronbach’s alpha At the moment, using AR technology is out of the question for me; I would rather wait to use it. Currently, I cannot imagine using AR technology, but maybe later I will. Right now, I would not use AR technology, but I can imagine using it in the future. Generally, I reject AR technology. I am against the use of AR technology. AR technology is not for me. I would take action to oppose the introduction of AR technology. I would participate in fan protests against the introduction of AR technology. I would support initiatives against AR technology. 4.24 1.40 .61 3.52 1.97 .93 2.44 1.70 .92 Table 5. Results of measurement invariance testing for Study 3. Model CFI ΔCFI RMSEA ΔRMSEA SRMR ΔSRMR Model 1 (UK): Model 2 (Germany): Model 3 (combined baseline model of free factor loadings & intercepts) Configural invariance established Model 4 (fixed factor loading against Model 3) Metric invariance established Model 5 (fixed factor loadings and intercepts against Model 4) Scalar invariance established .972 .969 .970 – – – .048 .048 .034 – – – .032 .037 .032 – – – .969 .001 .034 0.0 .032 0.0 .960 .009 .038 .004 .034 .002 with specifying equality constraints on the factor loadings across both groups (Model 4 in Table 5). Third, in addition to the factor loadings, the items’ intercepts were fixed (Model 5 in Table 5) to test scalar invariance. If all thresholds are met across the five models, measurement invariance is established. Afterwards, we conducted a CFA using the full sample to test additional measurement properties of all constructs (i.e. seven barriers and three resistance dimensions). We employed several measures to prevent and test for the occurrence of CMV because the data for all variables stem from the same cross-sectional source (Podsakoff et al., 2003). We followed the guidelines of the methodological literature (Hulland et al., 2018; Williams et al., 2010). First, the dependent and independent variables were separated in the questionnaire, and were measured using different scale formats (five-point vs. seven-point rating scales). Further, filler variables interrupted the response flow. For example, we included measures of adoption drivers, such as ease of use, to have not only a physical, but also a content-based separation. Second, three attention checks were integrated ensuring that respondents carefully read through the items. Third, a marker variable was included capturing respondents’ global identity (3 items [Tu et al., 2012]; α = .68) to statistically test the occurrence of CMV (Williams et al., 2010). To further account for CMV at the item level, an unobserved latent method factor was integrated into a CFA with all items loading on both their respective construct and the method factor (Podsakoff et al., 2003). Journal of Global Sport Management 561 Finally, the second-order structure of the barriers was tested conducting a CFA. Next, a structural equation model with barriers as the independent variable, and the three dimensions of resistance as dependent variables, as well as innovativeness, age, gender, and knowledge about AR as control variables, tested the relationships among the constructs. 5.2. Results 5.2.1. Measurement Properties and Common Method Variance (CMV) Table 5 presents the results of the measurement invariance tests in detail. Configural invariance, metric invariance and scalar invariance were established and we collapsed both samples for further analyses. The results of the CFA with the full sample indicated a good overall model fit (χ2 = 1167.69 df = 333, p < .001; χ2/df = 3.51; RMSEA = 0.046; CFI = 0.97; SRMR = 0.033; TLI = 0.97) (Bagozzi & Yi). All factor loadings were statistically significant (p < .001) and above 0.5. Construct reliability (ranging from 0.83 to 0.94) was established for all measures as their values exceeded 0.70 (Bagozzi & Yi, 2012). Further, the AVE values for all constructs (ranging from 0.63 to 0.83) exceeded 0.50, indicating good convergent validity (Hair et al., 2010). Moreover, for most constructs the square root of the AVE was higher than the highest correlation with any other construct, hence supporting discriminant validity (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). Only the correlation between loss of stadium atmosphere and fan identity incongruence was marginally higher than the square root of the AVE for fan identity incongruence. Regarding CMV, the marker variable showed several significant (p < .01) correlations with the study’s focal constructs (r ranging from 0.11 to 0.21), indicating the occurrence of a small to medium amount of CMV. The model with the unobserved latent method factor fitted the data very well (χ2 = 743.23, df = 304, p < .001; χ2/df = 2.45; RMSEA = 0.035; CFI = 0.99; SRMR = 0.018; TLI = 0.98) and a χ2-difference test indicated that adding the latent method factor significantly improves the model fit (χ2 = 424.46, df = 29, p < .001). Thus, the method factor was integrated into the structural model. 5.2.2. Second-Order Structure We considered a second-order structure as an appropriate modeling approach for the seven adoption barriers. Measurement theory recommends using second-order models when lower-order dimensions are highly correlated, and when these dimensions can be interpreted as reflections of a higher-order construct (Bagozzi & Yi, 2012). There are substantial correlations among all barriers, indicating empirical overlap. In addition, the barriers can be seen as belonging to a higher-level construct because all barriers represent reasons to resist the adoption of AR. This is in line with the conceptualizations of specific barriers in previous innovation resistance studies (e.g. Claudy et al., 2015). Thus, the second-order construct of barriers comprises all seven specific barriers to AR as first-order constructs. The CFA indicated a good model fit (χ2 = 754.036, df = 202, p < .001; χ2/df = 3.73; RMSEA = 0.048; CFI = 0.98; SRMR = 0.033; TLI = 0.97), and all first-order and second-order loadings are statistically significant (p < .001). 562 K. UHLENDORF AND S. UHRICH Table 6. Results for the structural model of Study 3. Paths Barriers → Interference with fan rituals supporting the team Barriers → Distraction from the live experience Barriers → Reduced social interactions Barriers → Reduced emotionality in discussions Barriers → Risk of personal image damage Barriers → Fan identity incongruence Barriers → Loss of stadium atmosphere Barriers → Postponement Barriers → Rejection Barriers → Opposition Control1: Innovativeness → Postponement Control1: Innovativeness → Rejection Control1: Innovativeness → Opposition Control2: Age → Postponement Control2: Age → Rejection Control2: Age → Opposition Control3: Knowledge about AR → Postponement Control3: Knowledge about AR → Rejection Control3: Knowledge about AR → Opposition Control4: Gender → Postponement Control4: Gender → Rejection Control4: Gender → Opposition R2 Postponement Rejection Opposition Std. Estimates p 0.86 0.87 0.88 0.61 0.76 0.91 0.92 0.53 0.85 0.84 −0.16 −0.17 −0.07 0.05 −0.01 −0.05 0.02 0.02 0.09 0.03 −0.02 0.01 < .001 < .001 < .001 < .001 < .001 < .001 < .001 < .001 < .001 < .001 < .001 < .001 .084 .069 .701 .043 .485 .442 .038 .162 .241 .861 0.35 0.81 0.71 5.2.3. Structural Model The results of the structural model indicated a good model fit (χ 2 = 1641.08, df = 566, p < .001; χ2/df = 2.90; RMSEA = 0.04; CFI = 0.97; SRMR = 0.036; TLI = 0.97). Adoption barriers were positively and significantly related to the resistance dimensions of postponement (β = .53, p < .001), rejection (β = .85, p < .001), and opposition (β = .84, p < .001). All seven first-order adoption barriers are significantly (p < .001) associated with the higher-order construct of barriers. As indicated by the second-order loadings, the barriers loss of stadium atmosphere (γ = .92), fan identity incongruence (γ = .91), reduced social interactions (γ = .88), distraction from the live experience (γ = .87), and interference with fan rituals supporting the team (γ = .86) exhibit very strong associations with the higher-order construct. While also being significantly associated with the higher-order construct, reduced emotionality in discussions (γ = .61) and risk of personal image damage (γ = .76) are the weakest reflections of barriers. Table 6 displays the results in more detail. Further, we tested the relationships between adoption barriers and the three resistance forms across typical fan segmentation variables (i.e. fan identification, season ticket ownership, favorite sport) and two countries (UK and Germany) using multigroup analyses in AMOS. These additional analyses aimed to explore whether our findings generalize across different spectator groups. The results indicate that the influence of barriers on the resistance dimensions are consistent over different levels of fan identification (high vs. low), different sports (soccer vs. other), and types of ticket owners (season ticket ownership yes vs. no) and, thus, similar to the overall sample. The findings are also widely robust across the two countries, although Journal of Global Sport Management 563 the relationship between barriers and postponement was slightly stronger in the German sample (β = .59) compared to the UK sample (β = .44). 5.3. Discussion of Study 3 The study reveals that AR adoption barriers are significantly related to the three dimensions of spectator resistance. The finding that the strongest relationship occurred between barriers and the dimensions rejection and opposition is plausible because rejection appears to be the most straightforward representation of resistance, and spectators tend to actively oppose what they perceive as undesirable changes in their consumption habits (Merkel, 2012). Further, all specific adoption barriers significantly reflect the higher-order barriers construct. Thus, these findings confirm the result of the qualitative study, as the barriers identified represent distinct drivers of spectator resistance to AR technology. 6. General Discussion 6.1. Theoretical Implications Previous research on spectators’ evaluations of technological innovations in general, and AR in particular, has taken a positive view and examined the influence of adoption drivers that facilitate technology acceptance (e.g. Goebert & Greenhalgh, 2020; Rogers et al., 2017). While such research offers important insights, our focus on spectator resistance provides a complementary perspective that is needed for a full understanding of spectators’ responses to technological advancements such as AR. Specifically, our work explores adoption barriers relating to smartphone-based AR usage within the stadium, and examines how these barriers are linked to spectator resistance. In doing so, we make a contribution by complementing existing work on the drivers of AR adoption (Goebert & Greenhalgh, 2020; Rogers et al., 2017). Our study provides detailed insight into the factors that lead sport spectators to resist AR technology in the stadium. The qualitative study identified seven barriers representing different facets of the stadium visit that are in conflict with AR usage. While these seven dimensions can be subsumed under the general adoption barriers included in Ram and Sheth’s (1989) classification, our exploration recontextualizes this model, and reveals some notable amendments and extensions. First, we show the particular relevance of usage barriers for in-stadium AR technology, because four of the seven identified barriers represent factors that contrast with spectators’ existing consumption practices and routines. This is in line with previous innovation-specific research showing that not all of Ram and Sheth’s (1989) general adoption barriers are equally important for all innovations (De Bellis & Johar, 2020; Mani & Chouk, 2018). Second, we extend the Ram and Sheth (1989) model by relating the adoption barriers to three different forms of resistance. This model has only considered the concept of resistance in general and subsequent applications examining different forms of resistance are restricted to qualitative inquiries (Kleijnen et al., 2009). Thus, we do not only show that AR adoption barriers relate to resistance, but also delineate specific effects on different manifestations of resistance, hence providing more theoretical nuance. 564 K. UHLENDORF AND S. UHRICH The present research also makes a broader contribution beyond AR technology by offering the first inquiry regarding innovation resistance in the sport consumer behavior literature. Uhrich’s (2022) work on fan experience apps included adoption barriers, but these were only linked to adoption attitudes, intentions, and behavior, and showed negative relationships. By considering sport spectator resistance and its three manifestations as the dependent variables, our study extends this previous work because it shows that adoption barriers can have unique consequences beyond simply negative attitudes and non-adoption, thus providing a more granular view of the consequences of AR adoption barriers. These consequences range from temporal uncertainty about adopting the technology to negative word of mouth, or even spectator protests. We show that barriers are strongly related to the resistance dimension of rejection, which represents an enduring negative attitude, and which appears to be conceptually close to the general concept of non-adoption. However, importantly, we find that barriers are also strongly related to opposition, a resistance dimension that reflects active engagement of the spectators in behaviors (e.g. negative word-of-mouth) aimed at preventing the diffusion of AR. This provides support for the notion that sport fans tend to actively express their opinions against undesired changes, and may engage in boycotts and protests (Cocieru et al., 2019). Further, we find that barriers are also related to postponement, although the magnitude of this relationship is lower compared to rejection and opposition. This comparatively weak link is not unexpected because it is likely that other factors also drive postponement in addition to adoption barriers. For example, Szmigin and Foxall (1998) suggest that situational factors (e.g. temporary budget constraints on the consumers’ side) often influence postponement. We further show that these relationships are robust across different levels of fan identification, different sports, and ticket categories, which speaks to the generalizability of the findings. Thus, the negative consequences that come with adoption barriers manifest within sport spectators, regardless of different fan characteristics. 6.2. Managerial Implications Our research offers important managerial implications. Broadly, the study advises marketers to not only focus on the benefits and advantages of AR, but also to consider its downsides. Two aspects of our study’s results are particularly important for marketers to incorporate in their marketing decisions regarding the introduction of AR. First, sport spectators have technology-specific reasons against the use of AR that marketers must address as early as possible in the technology’s introduction process. Second, these barriers lead to distinct forms of spectator resistance associated with different behaviors on the spectator side. Here, marketers must take effective countermeasures to mitigate these consequences. Regarding AR-specific adoption barriers, our work highlights that technology features creating these barriers should be addressed before introducing the technology. Thus, clubs and leagues should already be taking into account these features when app developers or agencies present their products and thoughts on introducing AR. This means they should ask, in particular, to what extent the developers are able to evade possible barriers Journal of Global Sport Management 565 and subsequently evaluate countermeasures. For example, the issue of distracting supporters from the live experience might be tackled by restricting AR visualizations to only some parts of the game (e.g. during a break for the video assistant referee) and by showing individual statistics at a time (e.g. the speed of the players). Considering such elements before introducing AR enables the development of a technology design that minimizes barriers and fits the consumption context with its traditions, routines, and rituals. Our study further demonstrates that AR adoption barriers have a distinct influence on different manifestations of spectator resistance. For example, barriers have a substantial influence on the resistance form of opposition, where responses include spreading negative word of mouth or calling for boycotts. Such detrimental behaviors may have consequences for clubs and leagues that go beyond AR technology. That is, oppositional reactions might damage the image of the club or league, and may even diminish the spectators’ identification with the sports property. This is because adoption barriers do not only relate to consumption practices, but also to spectators’ identity as sport fans. This highlights the importance of considering technology resistance and developing effective countermeasures. 6.3. Limitations and Future Research First, our study is only the beginning of understanding spectator resistance to AR and its drivers. While we tested the generalizability of our results across important fan segmentation variables, we did not explore other potential boundary conditions. For instance, fans who often take action against undesired changes initiated by the club might also be more likely to show oppositional behavior compared to fans who do not show such tendencies. Future studies can address this limitation by integrating possible moderating factors into the model of spectator resistance that go beyond the segmentation variables we used, thus further enriching understanding of this complex construct. Second, we developed measures for the identified AR adoption barriers based on the qualitative data and tested the scales using two pretests that provide wide support for their discriminant validity. Despite taking care in the development of the measures, it remains uncertain as to whether the need to model the barriers as a second-order construct rests on the theoretical fact that a higher-order concept accounts for the barriers, or if the measures were simply unable to capture the unique aspects of each barrier. The fact that several previous innovation resistance studies (e.g. Claudy et al., 2015; Tandon et al., 2020; Uhrich, 2022) found the empirical necessity to model barriers as a second-order construct supports the notion of barriers being a second-order construct. Moreover, both Ram and Sheth (1989) in their original work and subsequent studies based on this work do not provide empirical evidence for the independence of the adoption barriers (e.g. Joachim et al., 2018; Laukkanen et al., 2007). Further, it might be possible that in the current early stage of AR diffusion consumers are able to differentiate several barriers in in-depth interviews, while this seems more difficult when responding to a quantitative survey. Whatever might cause the empirical overlap, things may change as AR technology 566 K. UHLENDORF AND S. UHRICH diffusion increases. This is because with more experience, spectators may be better able to recognize the distinct features of specific barriers, and separate them from other barriers. This offers opportunities for interesting future research. Studies could examine whether adoption barriers are a higher-order construct in the early stages of innovation diffusion, while clearly separable dimensions occur in later stages. It would then be interesting to delineate individual influences of specific barriers on the three manifestations of resistance. Finally, we asked respondents to report their level of agreement with the three manifestations of resistance. Since the majority of spectators have not had the chance to use in-stadium AR technology, the answers represented intentions and opinions regarding a very early stage innovation. Since to this day, in-stadium AR technology is only available to a selected group of spectators for testing purposes in the examined countries, we were unable to capture actual behavior. Thus, we cannot be confident that the intentions reported by the participants will turn into behavior. Future studies conducted when in-stadium AR technology is more widely available will be able to assess resistance in a way that better reflects spectators’ actual evaluations and behaviors, rather than their predictions. Note 1. The preregistration document is available at https://aspredicted.org/8qe7j.pdf Disclosure Statement No potential conflict of interest has to be reported. Funding This work was supported by the Internal Research Funds of the German Sport University Cologne under Grant L-11-10011-235-061000. Notes on contributors Kim Uhlendorf (M.Sc.) is a PhD Student at the Institute of Sport Economics and Sport Management at the German Sport University Cologne in Germany. Her research interest focuses on the marketing of technological innovations from a consumer perspective. She has published in the Journal of Global Sport Management. Sebastian Uhrich (Ph.D.) is a Professor at the Institute of Sport Economics and Sport Management at the German Sport University Cologne in Germany. His research centers on consumer behavior in sport and has been published in various journals, including Journal of Business Research, Psychology and Marketing, Journal of Sport Management, European Sport Management Quarterly, Sport Management Review, among others. ORCID Kim Uhlendorf Sebastian Uhrich http://orcid.org/0000-0002-7815-0768 http://orcid.org/0000-0003-1099-1795 Journal of Global Sport Management 567 References Antioco, M., & Kleijnen, M. (2010). Consumer adoption of technological innovations. European Journal of Marketing, 44(11–12), 1700–1724. https://doi.org/10.1108/ 03090561011079846 Artillery. (2022). Mobile AR global revenue forecast, 2021–2026. Retrieved August 8, 2022, from https://artillry.co/artillry-intelligence/mobile-ar-global-revenue-forecast-2021-2026/ Bagozzi, R. P., & Yi, Y. (2012). Specification, evaluation, and interpretation of structural equation models. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 40(1), 8–34. https://doi. org/10.1007/s11747-011-0278-x Berryman, D. (2012). Augmented reality: A review. Medical Reference Services Quarterly, 31(2), 212–218. https://doi.org/10.1080/02763869.2012.670604 Capgemini Research Institute. (2020). Emerging technologies in sports: Reimagining the fan experience. Retrieved July 21, 2021, from https://www.capgemini.com/de-de/wp-content/ uploads/sites/5/2020/01/Studie_Emerging-Technologies-in-Sports_2020_Capgemini.pdf Casidy, R., Claudy, M., Heidenreich, S., & Camurdan, E. (2021). The role of brand in overcoming consumer resistance to autonomous vehicles. Psychology & Marketing, 38(7), 1101– 1121. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21496 Castillo, S., M J., & Bigne, E. (2021). A model of adoption of AR-based self-service technologies: A two country comparison. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 49(7), 875–898. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJRDM-09-2020-0380 Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory. Sage. Chen, F. F. (2007). Sensitivity of goodness of fit indexes to lack of measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 14(3), 464–504. https://doi. org/10.1080/10705510701301834 Cheung, G. W., & Rensvold, R. B. (2002). Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 9(2), 233–255. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_5 Claudy, M. C., Garcia, R., & O’Driscoll, A. (2015). Consumer resistance to innovation - a behavioral reasoning perspective. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(4), 528–544. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0399-0 Cocieru, O. C., Delia, E. B., & Katz, M. (2019). It’s our club! From supporter psychological ownership to supporter formal ownership. Sport Management Review, 22(3), 322–334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2018.04.005 Cowan, K., Javornik, A., & Jiang, P. (2021). Privacy concerns when using augmented reality face filters? Explaining why and when use avoidance occurs. Psychology & Marketing, 38(10), 1799–1813. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21576 Creswell, J. W. (2013). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Sage. Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly, 13(3), 319–340. https://doi.org/10.2307/249008 De Bellis, E., & Johar, G. V. (2020). Autonomous shopping systems: Identifying and overcoming barriers to consumer adoption. Journal of Retailing, 96(1), 74–87. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.jretai.2019.12.004 DFL. (2019). Kick-off for 5G: Latest mobile communications technology activated in the first Bundesliga stadium. Retrieved January 12, 2022, from https://www.dfl.de/en/news/kick-of f-for-5g-latest-mobile-communications-technology-activated-in-the-first-bundesliga-stadium/ EFL. (2019). English football league report. Retrieved August 3, 2021, from https://www.efl. com/contentassets/5fd7b93168134ee0b9da11fa8e30abd0/efl-supporters-survey-2019-report.pdf eMarketer. (2020). US virtual and augmented reality users 2020. Retrieved August 3, 2021, from https://www.emarketer.com/content/us-virtual-and-augmented-reality-users-2020 Facit Digital. (2018). Digitales Stadionerlebnis [Digital Stadium experience]. Retrieved September 26, 2021, from https://www.facit-group.com/content/dam/facit/facit-digital-com/studien/ Report_Digitales%20Stadionerlebnis.pdf 568 K. UHLENDORF AND S. UHRICH Fischer, E., & Guzel, G. T. (2022). The case for qualitative research. Journal of Consumer Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcpy.1300 Forbes. (2019). Dallas cowboys use augmented reality in popular new fan activation ‘pose with the pros’. Retrieved July 27, 2021, from https://www.forbes.com/sites/simonogus/2019/09/13/ dallas-cowboys-use-augmented-reality-in-popular-new-fan-activation-pose-with-the-pros/ Forbes. (2020). AI and AR tech lets soccer fans digitally attend matches behind closed doors. Retrieved October 21, 2021, from https://www.forbes.com/sites/stevemccaskill/2020/05/22/ ai-and-ar-tech-lets-soccer-fans-attend-matches-behind-closed-doors/ Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi. org/10.1177/002224378101800104 Forslund, M. (2017). Innovation in soccer clubs–the case of Sweden. Soccer & Society, 18(2–3), 374–395. FSA. (2017). National Supporters Survey 2017. Retrieved August 3, 2021, from https://thefsa. org.uk/news/national-supporters-survey-2017-more-results/ Gatignon, H., & Robertson, T. S. (1989). Technology diffusion: An empirical test of competitive effects. Journal of Marketing, 53(1), 35–49. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224298905300104 Goebert, C., & Greenhalgh, G. P. (2020). A new reality: Fan perceptions of augmented reality readiness in sport marketing. Computers in Human Behavior, 106, 106231. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.106231 Grau, A., Hövermann, A., Winands, M., & Zick, A. (2016). Football fans in Germany: A latent class analysis typology. Journal of Sporting Cultures and Identities, 7(1), 19–31. https:// doi.org/10.18848/2381-6678/CGP/v07i01/19-31 Hair, J. F., Anderson, R. E., Babin, B. J., & Black, W. C. (2010). Multivariate data analysis: A global perspective. Pearson. Heidenreich, S., & Spieth, P. (2013). Why innovations fail—The case of passive and active innovation resistance. International Journal of Innovation Management, 17(05), 1350021– 1350042. https://doi.org/10.1142/S1363919613500217 Hilken, T., de Ruyter, K., Chylinski, M., Mahr, D., & Keeling, D. I. (2017). Augmenting the eye of the beholder: Exploring the strategic potential of augmented reality to enhance online service experiences. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 45(6), 884–905. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-017-0541-x Hulland, J., Baumgartner, H., & Smith, K. M. (2018). Marketing survey research best practices: Evidence and recommendations from a review of JAMS articles. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 46(1), 92–108. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-0170532-y Joachim, V., Spieth, P., & Heidenreich, S. (2018, May). Active innovation resistance: An empirical study on functional and psychological barriers to innovation adoption in different contexts. Industrial Marketing Management, 71, 95–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2017.12.011 Kang, S. (2014). Factors influencing intention of mobile application use. International Journal of Mobile Communications, 12(4), 360–379. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJMC.2014.063653 Kim, Y., Kim, S., & Rogol, E. (2017). The effects of consumer innovativeness on sport team applications acceptance and usage. Journal of Sport Management, 31(3), 241–255. https:// doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2015-0338 Kleijnen, M., Lee, N., & Wetzels, M. (2009). An exploration of consumer resistance to innovation and its antecedents. Journal of Economic Psychology, 30(3), 344–357. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.joep.2009.02.004 Kuisma, T., Laukkanen, T., & Hiltunen, M. (2007). Mapping the reasons for resistance to Internet banking: A means-end approach. International Journal of Information Management, 27(2), 75–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2006.08.006 Laukkanen, T., Sinkkonen, S., Kivijärvi, M., & Laukkanen, P. (2007). Innovation resistance among mature consumers. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 24(7), 419–427. https://doi. org/10.1108/07363760710834834 Journal of Global Sport Management 569 Laukkanen, T. (2016). Consumer adoption versus rejection decisions in seemingly similar service innovations: The case of the Internet and mobile banking. Journal of Business Research, 69(7), 2432–2439. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.01.013 Mani, Z., & Chouk, I. (2018). Consumer resistance to innovation in services: Challenges and barriers in the Internet of things era. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 35(5), 780–807. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpim.12463 Merkel, U. (2012). Football fans and clubs in Germany: Conflicts, crises and compromises. Soccer & Society, 13(3), 359–376. https://doi.org/10.1080/14660970.2012.655505 Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. The Journal of Applied Psycholog y, 88(5), 879–903. https://doi. org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879 Presseportal. (2017). Eishockey, Basket- oder Handball - Was kommt eigentlich nach König Fußball? [Ice hockey, basketball or handball – What comes after king soccer?]. Retrieved August 3, 2021, from https://www.presseportal.de/pm/122186/3637647 Ram, S., & Sheth, J. N. (1989). Consumer resistance to innovations: The marketing problem and its solutions. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 6(2), 5–14. https://doi.org/10.1108/ EUM0000000002542 Rogers, R., Strudler, K., Decker, A., & Grazulis, A. (2017). Can augmented-reality technology augment the fan experience? A model of enjoyment for sports spectators. Journal of Sports Media, 12(2), 25–44. https://doi.org/10.1353/jsm.2017.0009 Szmigin, I., & Foxall, G. (1998). Three forms of innovation resistance: The case of retail payment methods. Technovation, 18(6–7), 459–468. https://doi.org/10.1016/ S0166-4972(98)00030-3 Tan, Y. C., Chandukala, S. R., & Reddy, S. K. (2022). Augmented reality in retail and its impact on sales. Journal of Marketing, 86(1), 48–66. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022242921995449 Tandon, A., Dhir, A., Kaur, P., Kushwah, S., & Salo, J. (2020). Behavioral reasoning perspectives on organic food purchase. Appetite, 154, 104786. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2020.104786 The Wall Street Journal. (2016). The NHL’s infamous glow puck returns with a new ambition. Retrieved September 26, 2021, from https://www.wsj.com/articles/the-nhls-infamous-glo w-puck-returns-with-a-new-ambition-1474930368 Tu, L., Khare, A., & Zhang, Y. (2012). A short 8-item scale for measuring consumers’ local– global identity. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 29(1), 35–42. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.ijresmar.2011.07.003 Two Circles. (2018). Sport grows leisure share with 2018 attendance and spending records. Retrieved August 3, 2021, from https://twocircles.com/gb-en/articles/sports-golde n-decade-takes-attendance-and-spending-records-into-2018/ Two Circles. (2019). UK claims world capital of live sport title with record 2019 attendance. Retrieved August 3, 2021, from https://twocircles.com/gb-en/articles/uk-named-world-capita l-of-live-sport-following-new-attendance-analysis/ Uhrich, S. (2022). Sport spectator adoption of technological innovations: A behavioral reasoning analysis of fan experience apps. Sport Management Review, 25(2), 275–299. https:// doi.org/10.1080/14413523.2021.1935577 Wedel, M., Bigné, E., & Zhang, J. (2020). Virtual and augmented reality: Advancing research in consumer marketing. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 37(3), 443–465. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijresmar.2020.04.004 Williams, L. J., Hartman, N., & Cavazotte, F. (2010). Method variance and marker variables: A review and comprehensive CFA marker technique. Organizational Research Methods, 13(3), 477–514. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428110366036 Winand, M., & Fergusson, C. (2018). More decision-aid technology in sport? An analysis of football supporters’ perceptions on goal-line technology. Soccer & Society, 19(7), 966–985. Winand, M., Schneiders, C., Merten, S., & Marlier, M. (2021). Sports fans and innovation: An analysis of football fans’ satisfaction with video assistant refereeing through social 570 K. UHLENDORF AND S. UHRICH identity and argumentative theories. Journal of Business Research, 136, 99–109. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.07.029 Ziesmann, T., Amtsberg, J., Dierschke, T., Erll, C., Heyse, M., & Weischer, C. (2017). Daten aus der Kurve [Data from the grandstand]. Forschungsgruppe BEMA Institut für Soziologie Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster. Retrieved October 19, 2020, from https://repositorium.uni-muenster.de/document/miami/f6952966-d933-4884-9670-bbb08e8a8935/ working_paper_bema_2017_3.pdf Journal of Global Sport Management 571 Appendix Appendix A: Interview Guide for Study 1 Note: The interviews were conducted in German. What follows is a translation of the original interview guide. Introduction: • Short description of the general topic discussed in the interview (including definition of and explanations regarding AR technology) • Description of the interview process and its length • Privacy statement • Demographic questions regarding the respondents’ age and occupation • General questions about the respondents’ relationship toward team sports (e.g. Which team do you support? How often do you attend home games of the team? Do you have a season ticket?) Photo-elicitation: • Respondents were shown pictures of smartphone-based AR applications (different angles and contexts presented, e.g. live statistics, player figures) in the stadium context with clear explanations and indications regarding its usage (e.g. hold smartphone towards pitch) • After viewing the pictures with enough time, participants were asked to state general thoughts about the technology when seeing them. Block I: Perceived problems with the innovation in general • What problems do you see when using such a technological innovation? Can you specify these problems? Why would you not use AR in general? What reasons would you have to not use AR technology? Block II: Perceived problems during specific situations within the stadium • In which specific situations within the stadium and during the game would you experience the most problems using the technology? Why does it disturb you in these situations? What are concrete problems that you would encounter during such a situation? Block III: Influence of social components within the stadium • To what extent do friends and other fans around you in the stadium influence your opinions about AR? To what extent do they play a role in your decision to use the innovation during the game? Block IV: Perceived problems concerning the image of the innovation • What kind of people do you expect would use such an innovation? What makes these people different from you? Conclusion • How exactly would you express possible criticism toward such an innovation? • Summary of the interview’s conversation topics 572 Appendix B General Barrier Usage Barrier Definition (Ram & Sheth, 1989) Perception that the innovation is in contrast with existing practices and routines consumers regularly enact. Specific Barrier Definition Distraction from the live experience The innovation prevents supporters from watching the game and other actions happening within the stadium uninterruptedly. Exemplary quotes ‘I'm just afraid that I'll miss some crucial scenes, and especially in ice hockey there are many goals, a lot of offensive actions, shots, or spectacular tackles, and that’s what you want to see, that’s why you go to the arena, and that’s why I'd not use it [AR technology] during the game.’ (Basti) ‘While using the innovation, things are going on [in the stadium] that I might have been much more interested in, so for me that’s a reason not to use it at all. I visit the stadium to watch the game […] and this technology would simply distract me from it.’ (Achim) ‘I personally prefer to be very close to the playing field and all the action, but I don’t want to be distracted by a technology. I want to see everything directly, analog, so to say.’ (Uwe) Interference with fan The use of the innovation is ‘[…] clapping, singing, shouting, or doing a La Ola wave all these are rituals supporting the incompatible with rituals I typically engage in during a match and I would find it team engaging in typical fan annoying to use this technology while keeping on cheering for my rituals related to cheering team.’ (Conny) for the team. ‘I mean, typically there is a lot of chanting, clapping and stuff going on, and I just can’t participate if I have a smartphone in my hand to use the innovation. I simply can’t hold it and clap at the same time.’ (Lara) ‘I also show a fan behavior during the 90 minutes, where I get upset sometimes and where you just support the team almost continuously and I wouldn’t do that with a smartphone in my hand which is why such an innovation would only disturb me in this situation.’ (Peter) Reduced social The adoption of the ‘You don’t go to the stadium to just watch the game; you also want to interactions innovation causes a chat and share the excitement with your friends. I could imagine by reduction of social using AR technology the whole time […] you would not talk with interactions with other fans your friends anymore and enjoy the experience together.’ (Anton) in the stadium. ‘I mean, it is normal that you get to talk to everyone around you in the stands, there are even a few fans that you see again and again every game and this typical personal exchange would be completely missing if they are all concentrated on using AR.’ (Mirco) ‘I think this technology would cause the stadium visit to become very impersonal.’ (Peter) (Continued) K. UHLENDORF AND S. UHRICH Table B1. Classification of barriers, their integration into Ram and Sheth’s (1989) model, definitions, and exemplary quotes resulting from the qualitative study. Table B1. Continued General Barrier Consumers’ fear that the innovation is not accepted by relevant others. Specific Barrier Definition Reduced emotionality in discussions The information provided by the innovation alters heated discussions about critical match decisions toward data-driven, rational conversations. Risk of personal image damage Exemplary quotes ‘I want to form my own opinion about match decisions and discuss it among friends. But, if that is objectified by data, and by analyses, then the possibility of this emotional, subjective discussion with others about this scene is weakened or somewhat not possible anymore.’ (Bene) ‘I’m afraid that conversations would probably go in a completely different direction, it would be more like "did you see how fast he just ran", so really related to the stats that the app gives you, but not like currently where you’re having emotional discussions together and know everything better about what happened on the field.’ (Bjarne) ‘It’s typical to have heated exchanges, like: "That was such a crappy pass", and then you expect others to be like: "Yeah, really, he’s been playing like crap all season". But if you have this innovation and then say: “Wait a minute I'll have a look at his stats”, I don’t want to know that in this moment as it would take away all these typical emotions.’ (Lennart) Sport spectators’ fear of being ‘If other fans notice that I'm using this technology, I can imagine that I perceived as rude and/or could be a disruptive factor. The fans who are directly next to me earning direct criticism would certainly say something like “Don’t you want to watch the from relevant people game? You aren’t here for the team, but only for your innovation.” within the stadium. Such comments are common in my block and I’d not want to disturb others.’ (Mirco) ‘I'm afraid that the spectators sitting around me would grumble very quickly. Therefore I’d rather not use it.’ (Angelika) ‘I would certainly feel ashamed myself using it [the innovation] too often if I knew that the person sitting behind me would see worse as a result.’ (Florian R.) (Continued) Journal of Global Sport Management Social Risk Definition (Ram & Sheth, 1989) 573 574 General Barrier Definition (Ram & Sheth, 1989) Specific Barrier Tradition Barrier Evaluation that the innovation causes a deviation from established norms of a social group relevant to the consumer. Loss of stadium atmosphere Image Barrier The degree to which an Fan identity innovation is perceived incongruence as having an unfavorable image. Definition Exemplary quotes Sport spectators’ concern that ‘I think that it would develop toward a typical fan who sits, doesn’t using the innovation would participate in fan-actions, and deals with the technology rather than cause the typical stadium contributing to the atmosphere. I fear that at some point people will atmosphere to be lost or only have their smartphones in their hands using AR, and as a result, changed for the worse. the atmosphere will be lost.’ (Jonathan) ‘That’s exactly what I'm afraid of, if suddenly the spectators instead of having the scarf in their hand, have their smartphones in their hand, I think the whole stadium atmosphere would get lost this way.’ (Mario) ‘What I find most problematic about it is, if at some point everyone stands there with their smartphone using AR technology and just stares at it, then a lot of the typical atmosphere itself could get totally lost.’ (Lennart) Incongruency between the ‘I think it [the innovation] would mostly be used by people who aren’t sport spectators’ fan interested in the game. But fans, like me, who are there for the identity (i.e. beliefs, values, game, the team, and the whole stadium experience, would for sure etc.) and the image of the not use this.’ (Lara) innovation as it stands for ‘For me, using a technology like this is not part of the fan behavior I commercialization and typically exhibit, nor is it part of what I see next to me.’ (Uwe) inauthentic fan behavior. ‘People who don’t go to the stadium often and don’t know what’s going on there would probably use it, but spectators like me who are authentic fans, who follow the action, they wouldn’t accept it.’ (Mario) K. UHLENDORF AND S. UHRICH Table B1. Continued Copyright of Journal of Global Sport Management is the property of Taylor & Francis Ltd and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.