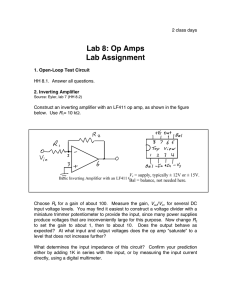

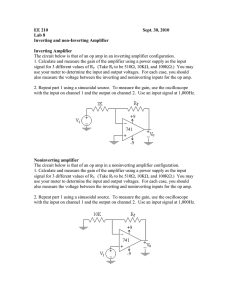

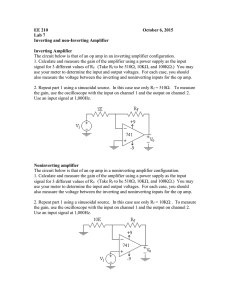

Electronics I (電子學一) Chapter II: 2.1 – 2.4 Transferred Electron Devices, and Sensors Prof. Tzu-Hsuan Chang Thurs & Friday 14:20 ~ 16:20 EEII 103 Fall 2024 TA: Dai-Jan Hu (r11k43033@ntu.edu.tw) Assist. TA: Ben-Yi Chu (r11k43033@ntu.edu.tw) 1 CHAPTER 2 Operational Amplifier • Chapter Outline 2.1 The Ideal Op Amp 2.2 The Inverting Configuration 2.3 The Noninverting Configuration 2.4 Difference Amplifiers 2.5 Integrators and Differentiators 1.6 DC Imperfections (skip) 2.7 Effect of Finite Open-Loop Gain and Bandwidth on Circuit Performance 2.8 Large-Signal Operation of Op Amps NTU 901 24110 (EE2009) Electronics (I) 2 Chapter 2.1 ~2.4 Summary ▪ IN THIS CHAPTER YOU WILL LEARN - The terminal characteristics of the ideal op-amp. - How to analyze circuits containing op-amps, resistors, and capacitors. - How to use op-amps to design amplifiers having precise characteristics. - How to design more sophisticated op-amp circuits, including summing amplifiers, instrumentation amplifiers, integrators, and differentiators. - Important non-ideal characteristics of op-amps and how these limit the performance of basic op-amp circuits. NTU 901 24110 (EE2009) Electronics (I) 3 Operational Amplifier (op amp) • • • • A circuit building block: op amp. One can do almost anything with op amps! Early op amps were constructed from discrete components and their cost was prohibitively high (tens of dollars). In the mid-1960s the first integrated circuit (IC) op amp was produced. Example: 𝜇A 709, 𝜇A 741, now tens of cents each. An IC op amp is made up of a large number (tens) of transistors, resistors, and (usually) one capacitor connected in a rather complex circuit. We will treat the op amp as a circuit building block and study its terminal characteristics and its applications. NTU 901 24110 (EE2009) Electronics (I) 4 Square Signal Generator with uA741 • With a circuit simulator, a quick analog circuit with output of a square wave signal can be generated https://www.circuitschools.com/square-wave-generator-circuit-with-op-amp-ic-741/ Circuit Symbol • Two input terminals (1 and 2) and one output terminal (3). • Terminal 4 and 5 (usually not explicitly shown): dc power supplies VCC and –VEE • More terminals: frequency compensation or offset nulling p.54 Ideal gain is defined: 𝑣3 = 𝐴(𝑣2 − 𝑣1) NTU 901 24110 (EE2009) Electronics (I) 6 Ideal OP AMP and its function: Function and Characteristics of an ideal OP AMP • An op amp senses the voltage difference between two input terminals 1 and 2 (i.e. 𝒗𝟐 − 𝒗𝟏), then multiply this by its gain 𝑨, then output 𝒗𝟑 = 𝑨(𝒗𝟐 − 𝒗𝟏) at terminal 3. • # Here 𝑣1, 𝑣2, 𝑣3 should have same reference ground. • Infinite input impedance: ✓ no input currents are drawn from signals. • Zero output impedance: ✓ independent of the current delivered to the load. ✓ The output voltage will always be 𝑣3 = 𝐴(𝑣2 − 𝑣1) no matter what load is connected. NTU 901 24110 (EE2009) Electronics (I) 7 Inverting and Non-Inverting Input Terminal: With output 𝑣3 = 𝐴(𝑣2 − 𝑣1), • • The output 𝑣3 is in phase with 𝒗𝟐 and is out of phase with 𝒗𝟏. So there is a “+” sign before terminal 2 and a “−” sign before terminal 1. • Input terminal 1 – ➢ Inverting input terminal (−). • Input terminal 2 – ➢ noninverting input terminal (+). • • Differential-input, single-ended output A: differential gain (open-loop gain without Load) NTU 901 24110 (EE2009) Electronics(I) 8 Ideal Op Amp 𝟐 Infinite open-loop gain A Infinite bandwidth (from dc to infinite frequency) Zero common-mode gain Infinite common-mode rejection Q: But, is an amplifier with infinite gain of any use? NTU 901 24110 (EE2009) Electronics (I) 9 Differential and Common-Mode Signals • An amplifier’s input is composed of two components… – differential input (vId) – is difference between inputs at inverting and non-inverting terminals – common-mode input (vIcm) – is input present at both inverting and non-inverting terminals common-mode input (vIcm ) differential input (vId ) vI = (10 + 1) − (10 − 1) = (10 − 10 ) + (1 + 1) • Similarly, two components of gain exist… – differential gain (A) – gain applied to differential input ONLY – common-mode gain (Acm) – gain applied to common-mode input ONLY e.g. v1 =10+1 e.g. v2 =10−1 common-mode output differential output vo = ( Acm 10 + A1) − ( Acm 10 − A1) = Acm (10 − 10 ) + A (1 + 1) NTU 901 24110 (EE2009) Electronics (I) 10 • Q: How is common-mode input (vIcm) defined in terms of v1 and v2? inverting input Common-mode input signal: 𝑣 𝐼𝑐𝑚 = 12(𝑣1 + 𝑣2) Differential input signal: 𝑣𝐼𝑑 = 𝑣2 − 𝑣1 • Internal circuit of a op amp can be modeled by the circuits shown below: 𝑣1 = 𝑣 𝐼𝑐𝑚 − 𝑣𝐼𝑑/2 𝑣2 = 𝑣 𝐼𝑐𝑚 + 𝑣𝐼𝑑/2 non- inverting input p.57 𝑣3 = 𝜇𝐺𝑚𝑅(𝑣2 − 𝑣1) NTU 901 24110 (EE2009) Electronics (I) 11 2.2 Inverting Configuration and Negative Feedback R2 closes the loop around the op amp. • • • • • R2: connected from the output terminal of the op amp, terminal 3, back to the inverting or negative input terminal, terminal 1 (−). We speak of R2 as applying negative feedback. If R2 were connected between terminals 3 and 2 (+) we would have called this positive feedback. R1: connected between input signal and op amp at terminal 1 Input 𝒗𝑰: input signal from terminal 1 (−) → Inverting Configuration Output 𝒗𝑶: voltage between terminal 3 and ground. (ideal output impedance = zero) It’s independent of current supplied to the load (if any). Closed-Loop gain G≡ 𝑣𝑂 𝑅2 =− 𝑣𝐼 𝑅1 “−” sign: phase shift of 180o with respect to input signal → Inverting configuration NTU 901 24110 (EE2009) Electronics (I) 12 Negative Feedback Connection 𝑣3 = 𝐴(𝑣2 − 𝑣1) In the following few pages, we will consider two cases: 1. Ideal Op AMP connected in negative feedback & inverting configuration 2. Ideal Op AMP with limited Gain A (A is not unlimited) connected in negative feedback & inverting configuration Case 1: Ideal Op AMP connected in negative feedback & inverting configuration differential input If vO is finite 𝑣𝑂 𝑣2 − 𝑣1 = =0 𝐴 A: infinite gain 𝑣2 = 𝑣1 → Virtual short circuit terminal 1: virtual ground 𝑖1 ≡ 𝑣𝐼 − 𝑣1 𝑣𝐼 − 0 𝑣𝐼 = = 𝑅1 𝑅1 𝑅1 Ideal op amp has infinite input impedance (no current going to op amp), so 𝑖1 can only flow through R2 to terminal 3. 𝑣0 = 𝑣1 − 𝑖1 𝑅2 = 0 − 𝑣𝐼 𝑅 𝑅1 2 𝑣𝑂 𝑅2 =− 𝑣𝐼 𝑅1 Gain depends entirely on external passive components! NTU 901 24110 (EE2009) Electronics (I) 14 • • • We can make the closed-loop gain as accurate as we want by selecting passive components of appropriate accuracy. The closed-loop gain is (ideally) independent of the op-amp gain. Negative feedback: We started out with an amplifier having very large gain A, and through applying negative feedback we have obtained a closed-loop gain R2/R1 that is much smaller than A but is stable and predictable. That is, we are trading gain for accuracy. Case II: Effect of Finite OpenLoop Gain Assume we have finite open-loop gain A 𝑣𝑂 𝑣𝑂 𝑣− = − ≠0 𝐴 𝐴 𝑣 𝑣1 − (− 𝐴𝑂 ) 𝑣1 + 𝑣𝑂 /𝐴 𝑖1 = = 𝑅1 𝑅1 𝑣+ − 𝑣− = infinite input impedance → 𝑖1 flow through 𝑅2 𝑣 𝑣𝐼 + 𝐴𝑂 𝑣𝑂 𝑣𝑂 𝑣𝑂 = − − 𝑖1 𝑅2 = − − 𝑅2 𝐴 𝐴 𝑅1 𝑣 −𝑅2 /𝑅1 𝑅2 Closed-loop gain: G ≡ 𝑂 = → − 𝑅 (ideal gain) 𝑅2 𝑣𝐼 1+ (1 + )/𝐴 1 𝑅1 (non-ideal gain) 𝑅 1 + 𝑅2 ≪ 𝐴 1 If A → infinite, inverting terminal→ virtual ground 𝑣𝑂 − →0 𝐴 11 Percentage error 𝜀 ≡ 𝐺 − 𝑅2 /𝑅1 × 100(%) 𝑅2 /𝑅1 Input and Output Resistances of a Closed-loop Amplifier (Inverting Configuration) • • Input resistance: R1 (ideal amp has infinite input resistance) Output resistance: 0 (output is a ideal voltage 𝑣𝑂 = 𝐴(𝑣2 − 𝑣1)) Page.59 This assumes that ideal op-amp and external resistors are considered “one unit” 𝑣𝐼 𝑣𝐼 𝑅𝑖 ≡ = = 𝑅1 𝑖1 (𝑣𝐼 − 0)/𝑅1 𝑣𝑂 𝑅2 =− 𝑣𝐼 𝑅1 • Remember we want high input resistance (R1) for fully deliver of source signal to our amplifier. What if we also need high gain? • R2 needs to be very large. (~ megaohms) → not very practical! • Inverting configuration suffers from a low input resistance. NTU 901 24110 (EE2009) Electronics (I) 16 Example 2.1 Consider the inverting configuration with 𝑅1 = 1 𝑘Ω and 𝑅2 = 100 𝑘Ω. (a)Find the closed-loop gain for the cases A = 103 , 104 , and 105 . In each case determine the percentage error in the magnitude of G relative to the ideal value of R2/R1(obtained with A = ∞). Also determine the voltage v1 that appears at the inverting input terminal when 𝑣𝐼 = 0.1 V. (b)If the open-loop gain A changes from 100,000 to 50,000 (i.e., drops by 50%), what is the corresponding percentage change in the magnitude of the closed-loop gain G? (a) 𝑣 −𝑅2 /𝑅1 G ≡ 𝑣𝑂 = 𝑅 1+ (1 + 2 )/𝐴 𝐼 𝑣1 = − 𝑅1 𝜀≡ (b) 𝑣𝑂 = −|𝐺|𝑣𝐼 /𝐴 𝐴 𝑣𝐼 = 0.1𝑉 𝐺 − 𝑅2 /𝑅1 × 100(%) 𝑅2 /𝑅1 Page.62 A |G| 𝜀 𝑣𝟏 103 90.83 -9.17 % -9.08 mV 104 99.00 -1.00 % -0.99 mV 105 99.90 -0.10 % -0.10 mV For A=50,000, |G|=99.80. Thus a -50% drop of the open-loop gain results in a change of only -0.1% in the closed-loop gain. NTU 901 24110 (EE2009) Electronics (I) 17 Low input resistance of negative feedback network 𝑅𝑖 ≡ 𝑣𝐼 𝑣𝐼 = = 𝑅1 𝑖1 (𝑣𝐼 − 0)/𝑅1 𝑣𝑂 𝑅2 =− 𝑣𝐼 𝑅1 The Gain of negative feedback op AMP comes from the ratio of −𝑅2 /𝑅1 To have high input resistance → 𝑅1 needs to be high (ex: 1MΩ) To have gain & low percentage error → 𝑅2 needs to be higher (ex: 100MΩ) Either power draining or heating Inverting configuration suffers from a low input resistance • We can resolve this issue using circuit design → check Example 2.2 Example 2.2 Assuming the op amp to be ideal, derive an expression for the closed-loop gain 𝑣𝑣𝑂 of the circuit 𝐼 shown in Fig 2.8. Use this circuit to design an inverting amplifier with a gain of 100 and an input resistance of 1 MΩ. Assume that for practical reasons it is required not to use resistors greater than 1 MΩ. Compare your design with that based on the inverting configuration of Fig. 2.5. Virtual ground → 𝑣− = 𝑣+ = 0 Page.63 𝑖1 = 𝑣𝐼 − 0 = 𝑖2 𝑅1 𝑣𝑥 = 0 − 𝑖2 𝑅2 = − 𝑖3 = 𝑣𝑂 = 𝑣𝑥 − 𝑖4 𝑅4 = 𝑣𝑥 − 𝑖2 + 𝑖3 𝑅4 = − 𝑅2 𝑣 𝑅1 𝐼 0 − 𝑣𝑥 𝑅2 = 𝑣 𝑅3 𝑅1 𝑅3 𝐼 𝑅2 𝑣𝐼 𝑅2 𝑣𝐼 − ( + 𝑣 )𝑅 𝑅1 𝑅1 𝑅1 𝑅3 𝐼 4 𝑣𝑂 𝑅2 1 𝑅2 =− −( + )𝑅 𝑣𝐼 𝑅1 𝑅1 𝑅1 𝑅3 4 NTU 901 24110 (EE2009) Electronics (I) 19 𝑣𝑂 𝑅2 1 𝑅2 =− − + 𝑅 = −100 𝑣𝐼 𝑅1 𝑅1 𝑅1 𝑅3 4 Let 𝑅2 = 1 MΩ Let 𝑅4= 1 MΩ For input resistance 𝑅1= 1 MΩ Page.59 1 1 + )𝑅4 = 99 1𝑀 𝑅3 ( 1𝑀 = 98 𝑅3 𝑅3 =10.2KΩ In comparison with the inverting configuration, if 𝑅1= 1 MΩ, we will need 𝑅2= 100 MΩ to achieve the gain of 100! No high resistance is needed! • 𝑅2 is in parallel with 𝑅3 due to virtual ground. • If 𝑖2 = 𝑖1 , the 𝑖3 = (𝑅2 /𝑅3 )𝑖2 , carrying 𝑘 = (𝑅2 /𝑅3 ) times of current of 𝑅2 • So 𝑖4 is (k+1) times of 𝑖2. This large current flows across the resistance 𝑅4 and gives a large voltage drop, hence a large 𝑣𝑜, without using a large resistance of 𝑅4. NTU 901 24110 (EE2009) Electronics (I) 20 Compare with the two negative feedback design: 1MΩ 1MΩ 1MΩ 10.2KΩ 100MΩ 1MΩ These two have the same close-loop voltage gain of 100 ! Application: The Weighted Summer • • • Rf : in the negative feedback path Different inputs vi with Ri connecting to inverting terminal Ri: “feed-in” resistor We have “virtual ground,” and by ohm’s law each branch will have a current of 𝑖𝑖 : 𝑣 𝑖= 𝑅𝑖 Total 𝑖 = 𝑖1 + 𝑖2 + ⋯ + 𝑖𝑛 forced to flow through 𝑅𝑓 will be 𝑅𝑓 𝑅𝑓 𝑅𝑓 𝑣𝑂 = 0 − 𝑖𝑅𝑓 = −𝑖𝑅𝑓 = −( 𝑣1 + 𝑣2 + ⋯ + 𝑣 ) 𝑅1 𝑅2 𝑅𝑛 𝑛 • • The output voltage is a weighted sum of the input signals 𝑣1, 𝑣2, ... 𝑣 𝑛. Summing coefficients are of the same sign. NTU 901 24110 (EE2009) Electronics (I) 22 Application: The Weighted Summer with summing coefficients of both signs 𝑣𝑥 𝑅𝑎 𝑅𝑎 𝑣𝑥 = − 𝑣 + 𝑣 𝑅1 1 𝑅2 2 𝑣𝑂 = −(𝑣𝑥 𝑣𝑂 = 𝑣1 𝑅𝑐 𝑅 𝑅 + 𝑣3 𝑐 + 𝑣4 𝑐 ) 𝑅𝑏 𝑅3 𝑅4 𝑅𝑎 𝑅𝑐 𝑅 𝑅 𝑅 𝑅 + 𝑣2 𝑎 𝑐 − 𝑣3 𝑐 − 𝑣4 𝑐 𝑅3 𝑅4 𝑅1 𝑅𝑏 𝑅1 𝑅𝑏 NTU 901 24110 (EE2009) Electronics (I) 23 2.3 The Noninverting configuration Remember: 1. Ideal op amp: infinite gain 2. Virtual short circuit between two input terminals 3. Current input is zero 4. Voltage output is always 𝑣𝑜 • • • • Input 𝒗𝑰: input signal from terminal 2 (+) → Noninverting Configuration Output 𝒗𝑶: voltage between terminal 3 and ground. (ideal output impedance = zero) It’s independent of current supplied to the load (if any). R1: grounded 𝑣𝑂 𝑅2 Inverting: G ≡ = − R2: closed-loop negative feedback 𝑣𝐼 𝑅1 NTU 901 24110 (EE2009) Electronics (I) 24 𝑣 𝐼𝑑 = 𝑣𝑜 𝐴 = 0 for 𝐴 → ∞ 𝑣−= 𝑣+ = 𝑣𝐼 𝑣𝐼 −0 𝑣𝑂 − 𝑣− 𝑖1= = 𝑖2 = 𝑅1 𝑅2 𝑣𝑜 = 𝑣𝐼 + Closed-loop gain voltage divider: Degenerative feedback: G≡ 𝑣𝑜 𝑣𝐼 𝑣𝐼 𝑅2 𝑅2 = 𝑣𝐼 (1 + ) 𝑅1 𝑅1 =1+ 𝑣𝐼 = 𝑣𝑂( 𝑅2 𝑅1 𝑅1 ) 𝑅1 + 𝑅2 𝑣𝐼+ ↑, 𝑣𝐼𝑑 ↑, 𝑣𝑂 ↑↑, voltage divider → 𝑣𝐼− ↑, 𝑣𝐼𝑑 ↓ back to zero → degenerative action NTU 901 24110 (EE2009) Electronics (I) 25 Effect of Finite Open-Loop Gain Assume we have finite open-loop gain A 𝑖2 𝑣𝑂 ≠0 𝐴 𝑣𝐼 − 𝑣− = 𝑖1 𝑣− 𝑖1 = 𝑣− = 𝑣𝐼 − 𝑣− − 0 𝑣𝐼 𝑣 𝑣 − 𝑣− = − 𝑂 = 𝑖2 = 𝑂 𝑅2 𝑅1 𝑅1 𝐴𝑅1 𝑣𝑜 = 𝑣− + 𝑖2 𝑅2 = 𝑣𝐼 − 𝑣𝑜 1 + In the inverting case: G≡ 𝑣𝑂 −𝑅2/𝑅1 = 𝑣𝐼 1 + (1 + 𝑅2)/𝐴 𝑅1 Same denominator → due to same feedback loop 𝑣𝑂 𝐴 G≡ 𝑣𝑂 𝑣𝐼 𝑣𝑂 +( − )𝑅 𝐴 𝑅1 𝐴𝑅1 2 1 1 𝑅2 𝑅2 + = 𝑣𝐼(1 + ) 𝐴 𝐴 𝑅1 𝑅1 𝑅 1 + (𝑅 2) 𝑣𝑂 1 = 𝑣𝐼 1 + (1 + 𝑅2)/𝐴 𝑅1 𝑅 → 1 + 𝑅2 (ideal gain) 1 (non-ideal gain) If 1 + R2 ≪ A (→ ∞) 𝑅 𝐼 Percent gain error 𝐺 − (1 + 𝑅2) 1 + 𝑅2 𝑅1 𝑅1 𝜀= =− × 100 (%) 𝑅 𝑅 2 2 (1 + ) 𝐴+1+ 𝑅1 𝑅1 NTU 901 24110 (EE2009) Electronics (I) 26 Input and Output Resistances of a Closed-loop Amplifier (Noninverting Configuration) • • Input resistance: infinite (ideal amp has infinite input resistance) Output resistance: 0 (output is a ideal voltage 𝑣𝑂 = 𝐴(𝑣2 − 𝑣1)) ◆ Voltage Follower (buffer amplifier) • • • • • Equivalent circuit model Buffer amplifier: no need to provide gain, only an impedance transformer If we set R1 = ∞, R2 = 0 → unity-gain amplifier or voltage follower (output “follows” input) If R2/R1 ≠ 0 → follower with gain Ideal case: 𝑣𝑂 = 𝑣𝐼, Rin = ∞, Rout = 0 100% negative feedback NTU 901 24110 (EE2009) Electronics (I) 27 2.4 Difference Amplifier • A difference amplifier is one that responds to the difference between the two signals (𝑣 𝐼𝑑) applied at its input and ideally rejects signals that are common to the two inputs (𝑣 𝐼𝑐𝑚). In practical circuit: • 𝑣𝑜 = 𝐴 𝑑 𝑣 𝐼𝑑 + 𝐴 𝑐𝑚 𝑣 𝐼𝑐𝑚 𝐴 𝑑 : amplifier differential gain 𝐴 𝑐𝑚 : common-mode gain (ideally zero) • Efficacy: the degree of its rejection of commonmode signals • Common-mode rejection ratio (CMRR) CMRR = 20 log │A d │ │A cm │ • • • Ideally, CMRR = infinity… The difference amplifiers are needed in the instrument front end to avoid directly measuring a small signal (e.g., 1mV) under a large interference signal (e.g., 1V) of instrument. Q: The op amp itself is differential in nature, why cannot it be used by itself? A: It has an infinite gain, and therefore cannot be used by itself. One must devise a closed-loop configuration which facilitates this operation. NTU 901 24110 (EE2009) Electronics (I) 28 Why we should not directly use a op AMP to amplify signal? • • • The difference amplifiers are needed in the instrument front end to avoid directly measuring a small signal (e.g., 1mV) under a large interference signal (e.g., 1V) of instrument. Q: The op amp itself is differential in nature, why cannot it be used by itself? A: It has an infinite gain, and therefore cannot be used by itself. One must devise a closed-loop configuration which facilitates this operation. Case 1 Case 2 What is the output 𝑣3 in this case? Suppose A ~ infinite NTU 901 24110 (EE2009) Electronics (I) 29 Difference Amplifier Under resistor matching condition: 𝑅4 𝑅 2 = 𝑅3 𝑅1 𝐴𝑐𝑚 = 0 1 𝑅4 𝐴𝑑 = ቊ 2 𝑅3 + 𝑅4 1+ 𝑅2 𝑅2 𝑅2 + ቋ= 𝑅1 𝑅1 𝑅1 𝑅2 𝑣𝑂 = 𝐴𝑑 𝑣𝐼𝑑 = 𝑣 𝑅1 𝐼𝑑 = 𝑅1 = 𝑅2 NTU 901 24110 (EE2009) Electronics (I) 30 Superposition Analysis P.73 Reduce 𝑣𝐼2 to zero Reduce 𝑣𝐼1 to zero P.74 𝑅4 𝑅2 = 𝑅3 𝑅1 P.74 𝑣𝑂1 = − 𝑅2 𝑣 𝑅1 𝐼1 matching 𝑣𝑂2 = 𝑣𝐼2 𝑅4 𝑅4 + 𝑅3 1+ 𝑅2 𝑅2 = 𝑣 𝑅1 𝑅1 12 Superposition 𝑅2 𝑅2 𝑣𝑜 = 𝑣𝑂1 + 𝑣𝑂2 = 𝑣 − 𝑣𝐼1 = 𝑣 = 𝐴𝑑 𝑣𝐼𝑑 𝑅1 𝐼2 𝑅1 𝐼𝑑 𝐴𝑑 = 𝑅2 𝑅1 To make this matching requirement a little easier to satisfy, we usually select 𝑅4 = 𝑅2 and 𝑅3 = 𝑅1 NTU 901 24110 (EE2009) Electronics (I) 31 Common-mode gain: apply common-mode signal to the input P.75 1 𝑅4 𝑣𝐼𝑐𝑚 − 𝑣 𝑅4 + 𝑅3 𝐼𝑐𝑚 𝑅1 𝑅3 1 = 𝑣 𝐼𝑐𝑚 = 𝑖2 𝑅4 + 𝑅3 𝑅1 𝑖1 = 𝑣𝑜 = 𝑅4 𝑣 − 𝑖 2𝑅 2 𝑅4 + 𝑅3 𝐼𝑐𝑚 𝑣𝑂 = 𝑅4 𝑅2 𝑅3 𝑣𝐼𝑐𝑚 − 𝑣 𝑅4 + 𝑅3 𝑅1 𝑅4 + 𝑅3 𝐼𝑐𝑚 Thus 𝐴 𝑐𝑚 = 𝑣𝑜 𝑅4 𝑅 𝑅 = (1 − 2 3 ) 𝑅4 + 𝑅3 𝑅1 𝑅4 𝑣 𝐼𝑐𝑚 = 𝑅4 𝑅4 + 𝑅3 1− 𝑅2 𝑅3 𝑣 𝑅1 𝑅4 𝐼𝑐𝑚 Design the resistor ratio to make 𝐴𝑐𝑚 = 0. Any mismatch can make it nonzero and CMRR finite. 𝑅4 𝑅 2 = 𝑅3 𝑅1 NTU 901 24110 (EE2009) Electronics (I) 32 Finding input resistance: apply difference signal to the input (seen by 𝑣𝐼𝑑) 𝑅𝑖𝑑 : differential input resistance Here we have predetermined the values of resistors: 𝑅4 = 𝑅2 and 𝑅3 = 𝑅1 P.75 𝑅𝑖 ≡ 𝑣𝐼𝑑 𝑖𝐼 Potential loop (virtual short) 𝑣𝐼𝑑 = 𝑅1𝑖𝐼 + 0 + 𝑅1𝑖𝐼 = 2𝑅1𝑖𝐼 𝑅𝑖𝑑 = 2𝑅1 • If we want a large differential gain (𝑅2/ 𝑅1), then 𝑅1 has to be relatively small → Low input resistance (drawback). • Q: And, what does this mean (practically)? → A: That source impedance will have an effect on gain. • Q: What is the solution? → A: Placement of two buffers at the input terminals, amplifiers which transmit the voltage level but draw minimal current. NTU 901 24110 (EE2009) Electronics (I) 33 A Superior Circuit: The Instrumentation Amplifier • • • The low-input-resistance problem of the difference amplifier can be solved by buffering the two input terminals using voltage followers. But, can we get some voltage gains from them than just impedance buffering? OK, the original idea is like this: we add two more op amps as the first stage and use them as voltage followers to fix the low input impedance problem. We leave the amplification and rejection of common-mode to the second stage op amp. 1st stage: Noninverting configuration P.76 2nd stage: difference amplifier • Output of 1st stage op amp: (1 + 𝑅𝑅2)𝑣𝐼1 , (1 + 𝑅𝑅2)𝑣𝐼2 • 1 1 Input of 2nd stage diff amp: 1+ 𝑅2 𝑅1 𝑣𝐼2 − 𝑣𝐼1 𝑅2 𝑣𝐼𝑑 𝑅1 • Output of 2nd stage diff amp: = 1+ Equivalent differential gain NTU 901 24110 (EE2009) Electronics (I) 𝑣𝑜 = 𝑅4 𝑅 (1 + 2)𝑣 𝐼 𝑅3 𝑅1 𝐴𝑑 = 𝑅4 𝑅 (1 + 2) 𝑅3 𝑅1 34 • • The common-mode signal will be rejected by 2nd stage amplifier. OK, now we can high input resistance (ideally infinite) and high differential gain. So far so good….but there are some issues… The input common-mode signal 𝑣 𝐼𝑐𝑚 is amplified in the first stage by a gain equal to that experienced by the differential signal 𝑣𝐼𝑑. This is a very serious issue, for it could result in the signals at the outputs of 𝐴1 and 𝐴2 being of such large magnitudes that the op amps saturate. But even if the op amps do not saturate, the difference amplifier of the second stage will now have to deal with much larger common-mode signals, with the result that the CMRR of the overall amplifier will inevitably be reduced. The two amplifier channels in the first stage have to be perfectly matched, otherwise a spurious signal may appear between their two outputs. Such a signal would get amplified by the difference amplifier in the second stage. To vary the differential gain 𝐴 𝑑, two resistors have to be varied simultaneously, say the two resistors labeled 𝑅1. At each gain setting the two resistors have to be perfectly matched, a difficult task. • • Q: What can we do to solve these issues? Simply disconnect the node between the two resistors labeled 𝑅1, node 𝑋, from ground. NTU 901 24110 (EE2009) Electronics (I) 35 Here we have lumped two R1. 1. Virtual short of A1, A2 2. No current into A1, A2 P.77 𝑣𝑂2 = 𝑣𝐼2 + 𝑣𝐼 𝑅 2𝑅1 2 𝑣𝐼𝑑 𝑅 𝑣𝑂1 = 𝑣𝐼1 − 2𝑅1 2 P.77 𝑅2 𝑅 𝑣𝑂2 − 𝑣𝑂1 = (𝑣𝐼2 − 𝑣𝐼1 ) + 𝑣𝐼𝑑 = 𝑣𝐼𝑑 (1 + 2) 𝑅1 𝑅1 This is the difference input of A3 𝑅4 𝑣𝑜 = 𝑣 − 𝑣𝑂1 𝑅3 𝑂2 = 𝐴𝑑 ≡ NTU 901 24110 (EE2009) Electronics (I) 𝑅4 𝑅 (1 + 2) 𝑣 𝐼 𝑅3 𝑅1 𝑣𝑜 𝑅4 𝑅 = (1 + 2) 𝑅3 𝑅1 𝑣𝐼𝑑 36 • Two 𝑅2 don’t need to be perfectly matched now. Indeed, if one of the two is of different value, say 𝑅2 ′ , the expression for 𝐴𝑑 becomes 𝑅4 𝑅2 + 𝑅2′ ) 𝐴𝑑 = (1 + 𝑅3 2𝑅1 • How about common-mode signals input? 𝑣𝑂1 = 𝑣 𝐼𝑐𝑚 P.77 𝑣 𝐼𝑐𝑚 The diff input is zero, no common-mode output! 𝑣𝑂2 − 𝑣𝑂1 = 0 𝑖=0 𝑣𝑂 = 0 𝑣𝑂2 = 𝑣 𝐼𝑐𝑚 • The difference amplifier in the second stage now has a much improve situation at its input: The difference signal has been amplified by (1 + R2/R1) while the common-mode voltage remained unchanged. • The gain can be varied by changing only one resistor, 2R1. NTU 901 24110 (EE2009) Electronics (I) 37 A Single-Op-Amp Difference Amplifier 𝑖2 𝑣+ = 𝑅4 𝑣𝐼2 = 𝑣− 𝑅3 + 𝑅4 𝑖1 𝑖 2 = 𝑖1 𝑣− 𝑣𝑂 − 𝑣− 𝑣− − 𝑣𝐼1 = 𝑅2 𝑅1 𝑣+ 𝑣− − 𝑣 𝐼1 𝑣𝑂 = 𝑣− + 𝑅2( ) 𝑅1 𝑅4 ( 𝑅4 𝑅 𝑅4 𝑅 𝑅3 + 𝑅4 𝑣𝐼2 − 𝑣𝐼1) 𝑣𝑂 = 𝑣𝐼2 + 𝑅2 = − 2 𝑣𝐼1 + ( )(1 + 2)𝑣𝐼2 𝑅3 + 𝑅4 𝑅1 𝑅1 𝑅3 + 𝑅4 𝑅1 𝑅4 𝑅2 𝑅 𝑣𝑂 = − (𝑣𝐼𝑐𝑚 − 𝑣𝐼𝑑 /2) + ( )(1 + 2)(𝑣 𝐼𝑐𝑚 + 𝑣𝐼d/2) 𝑅1 𝑅3 + 𝑅4 𝑅1 = 𝑅4 𝑅3 + 𝑅4 1+ 1 𝑅2 − 𝑅2 𝑣𝐼𝑐𝑚 + 2 𝑅1 𝑅1 𝑅4 𝑅3 + 𝑅4 1+ 𝑅2 + 𝑅2 𝑣 𝑅1 𝑅1 𝐼𝑑 𝐴𝑑 𝐴 𝑐𝑚 = 𝐴 𝑐𝑚 𝑣 𝐼𝑐𝑚 + 𝐴 𝑑 𝑣 𝐼𝑑 NTU 901 24110 (EE2009) Electronics (I) 38 We want the difference amplifier to reject common signals, so set common-mode gain = 0 𝐴𝑐 𝑚 = 𝑅4 𝑅3 + 𝑅 4 1+ 𝑅4 𝑅3 + 𝑅4 1+ 𝑅2 − 𝑅2 →0 𝑅1 𝑅1 𝑅2 = 𝑅 2 𝑅1 𝑅1 Matching condition 𝑅4 𝑅2 = 𝑅3 + 𝑅4 𝑅1 + 𝑅2 𝑅4 𝑅 2 = 𝑅3 𝑅1 Let’s take a look at the difference amplifier again. How do we connect it in this way? Inverting voltage divider |𝐺| = 𝑅2 𝑅1 Noninverting |G| = (1 + 𝑅2 ) 𝑅1 It’s a combination of inverting input (𝑣𝐼1 ) and noninverting input (𝑣𝐼2 ) configuration. We want the difference between them, and reject the common-signal of them. Inverting gain: 𝑅2 𝑅1 Noninverting gain: (1 + 𝑅2)( 𝑅4 ) (through the voltage divider → to attenuate gain (1 + 𝑅2 𝑅1 𝑅1 𝑅3+𝑅4 ) and make it equal to inverting gain 𝑅2, to reject common-mode signals) 𝑅1 NTU 901 24110 (EE2009) Electronics (I) 39 Example 2.3 Design the instrumentation amplifier circuit in Fig. 2.20(b) to provide a gain that can be varied over the range of 2 to 1000 utilizing a 100-kΩ variable resistance (a potentiometer, or "pot" for short) p.77 First stage: to get required gain Second stage: amplify difference signal and reject common-mode signal. Gain can be 1. 2R1: series combination of a fixed resistor R1f and the variable resistor R1v obtained using the 100-k Ω pot : To ensure the maximum available gain is limited We select all the second-stage resistors to be equal to a practically convenient value, say 10 k Ω. The problem then reduces to designing the first stage to realize a gain adjustable over the range of 2 to 1000. 𝐴𝑑 = 𝑅4 𝑅3 1+ 2𝑅2 = 1000 𝑅1𝑓 1+ 2𝑅1 = 𝑅1𝑓 + 𝑅1𝑣 1+ 𝑅2 𝑅1 =1+ 2𝑅2 =2 𝑅1𝑓 + 100 𝑘Ω NTU 901 24110 (EE2009) Electronics (I) 𝑅2 2𝑅2 =1+ 𝑅1 𝑅1𝑓 + 𝑅1𝑣 𝑅1𝑓 = 100.2 Ω (100 Ω) 𝑅2 = 50.050 𝑘Ω (49.9 𝑘Ω) Standard 1%-tolerance metal-film resistor 40