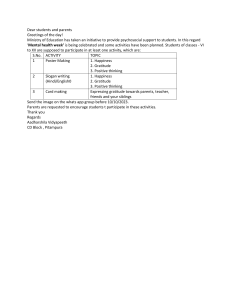

Luo et al. BMC Psychology (2025) 13:6 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-024-02337-w BMC Psychology Open Access RESEARCH The effect of responsible leadership on organizational citizenship behavior: double mediation of gratitude and organizational identification Jia Luo1,2, Lee-Peng Ng1* and Yuen-Onn Choong1 Abstract Background Organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) is a non-compulsory but beneficial behavior for effective organizational operation. OCB can be largely determined by the type of leadership style, among which responsible leadership has been attracting considerable attention in the organizational context nowadays. The objective of this study was to examine the parallel mediating effect of gratitude and organizational identification between responsible leadership and OCB among the academic staff in China. Methods This study employed a cross-sectional design by distributing self-administrative questionnaires to 317 faculty members from higher education institutions in China. SmartPLS 4.0 statistical software was employed to perform Partial Least Squares-Structural Equation Modelling, in which hypotheses were tested. Results The findings indicated that responsible leadership had a positive direct relationship with employees’ gratitude and organizational identification but not with OCB. Meanwhile, gratitude and organizational identification were found to improve OCB significantly. Furthermore, the results revealed that gratitude and organizational identification functioned as mediators between responsible leadership and OCB. Conclusions This study theoretically expanded existing research by employing a parallel mediation model between responsible leadership and OCB within an Asian higher education setting. Moreover, this study also presented practical suggestions for management and policymakers to devise strategies that can cultivate responsible leadership in higher education institutions to enhance employees’ gratitude and organizational identification, ultimately promoting OCB. Keywords Responsible leadership, Gratitude, Organizational identification, Organizational citizenship behavior *Correspondence: Lee-Peng Ng nglp@utar.edu.my 1 Faculty of Business and Finance, Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman, Kampar, Perak 31900, Malaysia 2 School of Business Administration, GuiZhou University of Finance and Economics, Guiyang, Guizhou 550025, China © The Author(s) 2024. Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creati vecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Luo et al. BMC Psychology (2025) 13:6 Introduction In the age of the knowledge-based economy, universities are expected to take on more prominent roles, broaden their missions, and actively fulfill social responsibility [1]. Chinese higher education institutions have made great strides in recent decades. However, it is still necessary to keep improving education quality, encouraging innovation and research, boosting the country’s university reputation internationally, and adapting to changing labor market demands [2, 3]. Therefore, the engagement of leaders and academic staff is essential to enable Chinese higher education institutions to confront these challenges. Responsible leadership is defined as leaders’ behavior of addressing stakeholder needs, balancing stakeholder interests, and building trust and reliability with stakeholders [4, 5]. In higher education, responsible leaders are essential for enhancing employees’ knowledge-sharing behavior [6], psychological contract [7], psychological safety [8], and work engagement and career success [9]. However, scandals about university leaders, including academic corruption and academic fraud, have become a problematic issue [10, 11]. Irresponsible leaders in educational institutions are primarily motivated by their own egomaniacal needs. Instead of empathizing, inspiring, and resolving conflicts, irresponsible leaders are more likely to inhibit moral development and discourage employees’ efforts and creativity [12]. Given the dark sides of irresponsible leadership, the call for responsible leadership is indispensable to respond to the constantly changing educational environment and promote the institution’s performance [13]. Meanwhile, academic staff is the most valuable human resource in the university. With the rising competition among higher education institutions, academic staff are expected to take on a broader range of responsibilities beyond teaching, including research, publication, consultancy, supervision, tutoring, and community services [14, 15]. The academic staff possesses the knowledge, creativity, and autonomy; thus, their organizational citizenship behavior (OCB), which refers to discretionary, nonreward-based behavior that improves the organization, is valuable to the university development, students’ learning process and the delivery of quality education [11, 16– 18]. Promoting OCB is essential given its favorable effect on academic staff ’s sense of fulfillment, job satisfaction, students’ achievements, students employability, as well as the overall effectiveness, sustainable competitive advantage, and image of the institution [19–21]. University leaders need to play a more critical role than previously in stimulating the momentum for extra-role behavior among academic staff beyond their formal required job functions. Notably, responsible leadership is a valuebased leadership that focuses on promoting meaningful Page 2 of 14 value and fostering a mutually beneficial leader-stakeholder relationship [22]. Therefore, responsible leadership is vital to encourage academic staff ’s self-driven, extra-role, and beneficial behaviors in today’s higher education landscape. The first objective of this study is to examine the relationship between responsible leadership and OCB among academic staff. While researchers generally advocate a positive relationship between responsible leadership and OCB [23, 24], inconsistent results were found between the two variables in past studies. For instance, Khanam and Tarab [25], as well as Freire and Gonçalve [26] found no significant direct effect of responsible leadership on OCB based on the samples of employees from the healthcare and hospitality sectors, respectively. This inconsistency suggests that the connection between responsible leadership and OCB needs further investigation in country-specific and industry-specific circumstances. There is still a research gap regarding the connection of these variables in the context of Chinese higher education. Moreover, the mixed findings suggest the significance of exploring the complex mechanism for how responsible leadership is related to OCB. Thus, the second objective is to examine the role of gratitude in mediating the relationship between responsible leadership and OCB. According to Affective Event Theory [27], employees’ attitudes and behaviors can be shaped by emotional responses that arise from workplace events. As an integral component of workplace interactions, leaders’ behavior can induce employees’ emotional reactions and shape their work attitudes and behaviors [27]. Thus, responsible leaders who prioritize employees’ interests and benefits will likely evoke feelings of gratitude and inspire their willingness to engage in OCB [28]. In recent years, organizational researchers have emphasized the need for more evaluations related to gratitude, as it is a positive psychology concept [29] known to benefit both employees and organizations [30]. Research has discovered different leadership styles that effectively elicit gratitude in employees, thus impacting their work behaviors. Examples include servant leadership [31, 32], inclusive leadership [33], sustainable leadership [34], and leaders’ forgiveness [35]. However, the extent to which responsible leadership can be a valuable stimulator of academic staff gratitude needs further validation. Meanwhile, the literature still lacks an assessment of the mediating effect of gratitude between responsible leadership and OCB. Existing research has mainly focused on the mediating role of gratitude between servant leadership and outcomes such as interpersonal citizenship behavior, upward voice, creativity, and organizational success [31, 32]. Therefore, investigating how responsible leadership explains OCB indirectly through gratitude deserves researchers’ attention. Luo et al. BMC Psychology (2025) 13:6 Third, we examined organizational identification as a mediator between responsible leadership and OCB. Previous research suggests that identification serves as a mediator between responsible leadership and various employees’ attitudes and behaviors [36], such as responsible leadership and employees’ creative idea-sharing [37], responsible leadership and organizational commitment, responsible leadership and work engagement [36], and responsible leadership and OCB [26]. Drawing on the Theory of Social Identity, leadership can be related to followers’ self-perception and sense of identification with the organization [38]. Responsible leaders prioritize ethical standards and the welfare of stakeholders, which foster a positive perception of the organization among employees [39]. In such a situation, employees will have a greater tendency to internalize the organization’s core values, nurturing a feeling of pride and a strong sense of belonging to the organization. More specifically, responsible leaders cultivate employee identification by demonstrating traits such as trustworthiness, openness, proactivity, and virtuousness. Consequently, employees who identify with the organization may feel personally connected to it and be more inclined to exert extra effort to contribute to its success [40]. Thus far, the extent to which organizational identification can be an effective mediator on the linkage between responsible leadership and OCB among academics in the Chinese higher education sector has yet to be established. Understanding this connection is essential in developing a supportive academic environment. Taken together, this study is positioned to make several significant contributions. Theoretically, the parallel mediation research model employed here provides a deeper understanding of the relationship between responsible leadership, gratitude, organizational identification, and OCB within the Chinese higher education context. This enhances the body of knowledge in organizational behavior literature. From a practical standpoint, this study is expected to offer valuable guidance to university administrators regarding the importance of cultivating responsible leadership to nurture a culture of gratitude among academic staff and enhance their sense of organizational identification. These efforts, in turn, can stimulate academic staff to engage in OCB. Literature review Underpinning theory The suggested model is underpinned by two theories: Affective Events Theory (AET) and the Social Identity Theory (SIT). AET describes the logical chain of emotional responses among organizational members to specific work events, ultimately leading to various outcomes. It elucidates the underlying reasons for emotional reactions and predicts subsequent behaviors [27]. AET has Page 3 of 14 been extensively embraced by numerous academics, particularly in studies focusing on gratitude [35]. According to AET, a leader’s conduct within the work environment can elicit emotions among individuals or teams, thereby shaping their subsequent behavior. Responsible leadership fosters positive emotions among subordinates by addressing the needs of diverse stakeholders and establishing a fair and ethical working environment [41]. Hence, it can be posited that responsible leaders’ behavior has the potential to evoke specific positive emotions, such as gratitude. On the other hand, SIT suggests that individuals often categorize themselves and others based on factors such as organizational belonging, religious affiliation, gender, and age group [42]. SIT has frequently served as a foundational framework for leadership studies [26, 40]. It posits that individuals’ identity is shaped by their awareness of belonging to social groups and the emotional significance they attribute to this membership [43]. According to SIT, promoting employees’ identification with the organization fosters positive behavior among the members [44]. Organizational identification refers to the alignment between an individual’s beliefs and objectives with those of the organization [45], hence resulting in greater involvement and more substantial commitment to the organization [46]. Responsible leadership and OCB A responsible leader is defined as someone who carefully considers the potential impact of decisions on all parties involved. They actively engage in stakeholder dialogue, assessing and balancing diverse interests [5]. This type of leadership has received significant attention due to growing concerns about organizational sustainability and responsibility [22, 26]. In higher education, an essential aspect of responsible leadership is cultivating collaborative relationships with various stakeholders, covering students, professors, parents, and the broader community [39]. Several empirical studies in the higher education realm show that responsible leadership is related to organizational dynamics. For example, responsible leadership is associated with the knowledge-sharing behavior of Chinese faculty members directly and indirectly through person-organization fit [6]. Research in Egypt suggests that the connection between organizational inclusion and psychological contract among academics was mediated by responsible leadership [7]. In Ugandan public universities, responsible leadership was found to positively correlate with psychological safety and supporting employee well-being [8]. Additionally, responsible leadership elevates work engagement and leads to career success, especially among employees with strong selfenhancement motives in Pakistan’s education sector [9]. Luo et al. BMC Psychology (2025) 13:6 On the other hand, OCB is defined as “individual behavior that is discretionary, not directly or explicitly recognized by the formal reward system, and that, in the aggregate, promotes the effective functioning of the organization” [47, p.4]. Williams and Anderson [48] further categorize OCB into two components: OCBI represents OCB directed towards specific individuals, and OCBO reflects a broader sense of conscientiousness towards the larger organization. The job nature of academic staff is relatively complex as they must deal with a wide range of duties, such as teaching, administration, student mentoring, and research. These required academic staff to be creative, flexible, and highly professional. In such diverse and demanding work conditions, the OCB of academic staff within the university becomes crucial [49]. Generally, past studies in non-academic settings, such as the pharmaceutical sector [24] and the Red Crescent Society [23], affirm that responsible leadership promotes OCB among employees. However, thus far, research examining the underlying relationship between responsible leadership and OCB, especially within the higher educational context, is currently limited. An extensive review revealed that while the existing body of research in higher education recognizes the importance of various leadership styles in shaping extra-role behavior among academic staff, the primary focus was on inclusive leadership [50], benevolent leadership [51], ethical leadership [52, 53], change leadership [54], transformational leadership [55], and servant leadership [56], with responsible leadership being overlooked. Responsible leaders, considering the well-being of multiple stakeholders, promote employees’ OCB by serving as role models and advocating for socially responsible initiatives, inspiring individuals to engage in behaviors that benefit both the organization and the community [57]. Leading by example fosters a sense of team awareness, altruism, and internal motivation among employees, which corresponds to the feature of OCB [49]. Responsible leadership encourages employees to focus on the interests of internal and external stakeholders and promotes workers’ sense of responsibility, including helping new colleagues, spending extra time tutoring students, and contributing to the community [51]. In light of this, it is proposed that responsible leadership can improve the OCB of academic staff. Responsible leadership, gratitude, and OCB Gratitude is defined as a discrete positive emotion with a dispositional component [58]. It manifests as a positive emotion that arises when an individual receives a benefit and attributes the event favorably [35, 59]. Employees may experience gratitude due to events involving leadership or helpful actions from colleagues [30]. Page 4 of 14 Past research has demonstrated that various factors, such as servant leadership [31, 32], employees’ perceived trust in their supervisor [58], leaders’ forgiveness [35], and perceived corporate social responsibility [60], can evoke feelings of gratitude among employees. Responsible leadership, characterized by its emphasis on fostering ethical and moral relationships with stakeholders [4, 61], involves considering the interests of all relevant stakeholders in decision-making [62]. This leadership approach also entails ensuring ethical employment practices, providing a safe work environment, prioritizing employees’ professional development, and ensuring job meaning and work-family balance [61]. Employees typically perceive these actions of responsible leadership as actively caring for and benefiting them, which is expected to stimulate their feelings of gratitude [59, 62]. Based on AET, leaders’ conduct during work events can be associated with the emotional responses of subordinates, thereby shaping their work attitudes and behaviors [27]. Employees’ psychological states, attitudes, and behaviors in the workplace are often associated with situational factors or events [27]. The intensity of these emotions may vary depending on the specific event. Previous research has identified that gratitude can positively relate to various types of OCBs, such as interpersonal citizenship behaviors [32], helping behaviors [63], and OCBO [64]. Employees who experience feelings of gratitude in the workplace are more inclined to engage in prosocial behaviors, including OCB, within the organizational context [58]. Therefore, it is hypothesized that gratitude, as a positive emotion, could serve as an indirect mechanism through which responsible leadership is related to employee voluntary behavior. Responsible leadership, organizational identification, and OCB Organizational identification refers to individuals’ cognitive connection between self-definition and the organization’s definitions [65]. It signifies a sense of unity with the organization, as well as a perception of the organization’s successes and failures as personally significant [66]. It involves individuals defining themselves based on their affiliation with a specific organization, making it a form of social identification [67]. Employees form a perception of their organization based on the behavior and voices of their leaders [36]. Effective leadership operates within the framework of shared goals and values [38], which are associated with followers’ sense of identification with the organization [67]. Employees modify their beliefs and behaviors by observing the behaviors of their leaders, especially those who are responsible [68]. Value-based leadership, such as ethical leadership [40, 69], transformational leadership [70, 71], and responsible leadership [36] have been Luo et al. BMC Psychology (2025) 13:6 testified to elicit organizational identification. Responsible leadership is also a value-based leadership that prioritizes the core values of integrity, honesty, courage, patience, trust, and respect [72]. By establishing a work environment that upholds ethical and supportive values, responsible leadership enhances employees’ satisfaction with their jobs and fosters a sense of obligation [73, 74]. To put it another way, responsible leaders prioritize transparency and open communication. This form of leadership fosters and maintains a trustworthy relationship with internal and external stakeholders [36]. Practice by responsible leaders, such as delegating and involving employees in decision-making and offering opportunities for employee development, can significantly increase employee engagement and commitment, which may yield a sense of identification and belongness among them [36]. Meanwhile, empirical evidence indicates that employees’ identification with the organization relates to its socially responsible practices [26]. For instance, socially responsible human resource management initiatives can enhance employee engagement in OCB by fostering a stronger sense of organizational identification [75]. Organizations perceived as socially responsible may be viewed as prestigious and reputable by employees, fulfilling their need for meaning and self-esteem and consequently favorably impacting their organizational identification [44, 76]. In a similar vein, the idea of responsible leadership was conceptualized by combining corporate social responsibility and leadership literature [77]. Their concern, care, and attention toward a range of stakeholders showed an overall responsibility [61]. Empirically, the connection between responsible leadership and organizational identification has been verified in the studies that involve participants from the hospitality industry and nonprofit organizations [26, 36]. Relatedly, we speculated that responsible leadership could enhance employees’ organizational identification. Employees with high organizational identification may experience a strong connection and alignment with the goals and demands of their organization [78]. Such alignment results in employees’ increased involvement and willingness to compromise with the organization [46]. They prioritize the interests of their organization as their own and make job-related decisions based on what is most beneficial for the organization [79]. Besides, employees with high organizational identification are more prone to contributing to the organization by making financial donations, encouraging others to join, and participating in organizational activities such as attending events [66]. Organizational identification has the potential to yield numerous positive outcomes for both employees and organizations. These include a greater dedication to the organization, higher staff retention Page 5 of 14 rates, reduced turnover intention, increased OCB, higher employee well-being and satisfaction, organizationalfriendly decision-making, and improved employee performance [26, 75, 80, 81]. Given the discussion mentioned above, we hypothesized that organizational identification could serve as a mediator in the relationship between responsible leadership and OCB. Hypotheses development Aligned with the research objectives, we aim to investigate whether responsible leadership predicts OCB. Besides, we contended that responsible leadership is indirectly related to OCB through the mediating mechanism of gratitude and organizational identification. Therefore, the hypotheses are presented as follows: Hypothesis 1 Responsible leadership is positively related to OCB. Hypothesis 2 Responsible leadership is positively related to gratitude. Hypothesis 3 Gratitude is positively related to OCB. Hypothesis 4 Responsible leadership is positively related to organizational identification. Hypothesis 5 Organizational identification is positively related to OCB. Hypothesis 6 Gratitude will mediate the relationship between responsible leadership and OCB. Hypothesis 7 Organizational identification will mediate the relationship between responsible leadership and OCB. Research model Figure 1 presents an overview of the research model. Research methodology Procedure and sample This study adopted a quantitative approach with a crosssectional design. The quota sampling technique was utilized to ensure the data’s representativeness and generalizability. The study was conducted in Guizhou, a culturally and economically diverse province in southwestern China. Data from the Ministry of Education China [82] shows Guizhou is home to 75 higher education institutions, including 28 universities. For this study, participants were selected from 10 prominent universities across the province, which offer broad academic disciplines, including finance and economics, education, Western and traditional Chinese medicine, engineering, science, and policing studies. Luo et al. BMC Psychology (2025) 13:6 Page 6 of 14 Fig. 1 Conceptual framework We employed self-administered questionnaires to collect data from the participants. To be eligible, respondents needed to be full-time academic staff members at universities. Additionally, respondents were required to have worked at the university for more than one year to ensure they had sufficient interaction with their leaders. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the university’s Scientific Review Committee, and consent was obtained from the management of each university. Subsequently, academic staff members were contacted and approached to participate in the survey from January 2024 to February 2024. A total of 400 questionnaires were distributed to academic staff who volunteered to participate in the survey. We included a cover letter in each questionnaire to minimize common method bias in data collection for self-report questionnaires. The cover letter outlined the survey’s purpose and assured respondents of both anonymity and confidentiality of their responses. Additionally, in the instructions, we urged the participants to respond truthfully and highlighted no correct or incorrect answers for their responses. Data collection was conducted using the Drop-off and Pick-up (DOPU) method. As an acknowledgment of participation in the paperbased survey, each respondent received a token of appreciation valued at 10 Chinese Yuan (CNY). Out of the 355 surveys returned, 317 were deemed usable. The remaining 38 surveys were incomplete, resulting in an effective response rate of 89%. The participants of this study consisted of 106 (33.4%) male and 211 (66.6%) female academic staff. Out of the entire survey sample, 1.6% of respondents were 25 years old and below, 35% were between the ages of 26 and 35, 51.4% were between the ages of 36 and 45, 10.4% were between the ages of 46 and 55, and 1.6% were 56 years old and above. On the other hand, 66.9% of the academic staff possessed a master’s degree, 24.6% held a doctorate degree, and 8.5% were with other qualifications. Finally, 11% of the respondents were assistant lecturers, 47% were lecturers, 29% were associate professors, 8% were professors, and 5% were classified in other categories. Research instrument Responsible leadership was assessed using the scale developed by Voegtlin [83], which comprises 5 items. Participants were asked to reflect on the leader with whom they interacted most frequently and rate that leader on a five-point Likert scale. The scale developed by Voegtlin [83] is widely recognized and frequently utilized in academic research. A minor adjustment was made to one item to enhance clarity regarding the concept of stakeholders in the university context. The adapted scale Luo et al. BMC Psychology (2025) 13:6 Page 7 of 14 demonstrates good internal consistency, as well as discriminant and predictive validity, across various studies [84–86]. An example item from the scale is “My immediate superior will thoroughly consider the impact of his/ her decision on the stakeholders”. Gratitude was operationalized by adapting the State Gratitude Scale developed by Spence et al. [58]. This five-item scale is commonly used to evaluate employees’ affective states in the workplace [58]. Modifications were applied to the original items to reflect employees’ feelings of gratitude more accurately toward their leader. Sample items include “I feel grateful for my immediate superior” and “I am happy to have been helped by my immediate superior”. Organizational identification was assessed using a sixitem scale adapted from the original work of Mael and Ashforth [66]. Sample items from this scale include “I consider it a personal offense when someone criticizes the university I work for” and “The achievements of the university I work for are my own successes”. Organizational citizenship behavior was assessed by adapting the scale developed by Williams and Anderson [48]. This scale comprises two dimensions: organizational citizenship behavior towards individuals (OCB-I) and organizational citizenship behavior towards the organization (OCB-O). Each dimension of OCB—OCB-I and OCB-O—consists of seven items, totaling 14 items. This scale has demonstrated validity and reliability across various studies [87–89]. Sample items are “I find it is a personal offense when someone criticizes the university I work for” and “The successes of the university I work for are my successes”. All adapted measurement items in this study were evaluated using a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 for strongly disagree to 5 for strongly agree. The questionnaire was translated into Chinese following the guidelines of [90] using the back-translation method. To ensure the appropriateness of the survey instrument, a pre-test was conducted by inviting five academic staff who are experts in the field to assess the content validity of the questionnaire. Subsequently, a pilot study involving 30 respondents was conducted, and the reliability of each measure used in this study was found to be satisfactory. Data analysis The data collected for this research were first analyzed using SPSS version 27, which involved descriptive analysis, correlation analysis, and evaluation of common method bias. Subsequently, SmartPLS version 4.0.9.9 was used to perform Partial Least Squares-Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM) to ascertain the path relationships among variables. PLS-SEM is well-suited to evaluate a complex model consisting of diverse constructs and indicators [91]. Besides, in contrast to covariance-based structural equation modeling, PLS-SEM possesses greater predictive capabilities; it not only can deal with small datasets but also works well for large sample sizes and does not have a strict requirement for normal data [92, 93]. In sum, PLS-SEM is suitable for evaluating multiple mediation analyses in this study and enabling the understanding of the structural relationships between the latent variables. In the analysis of PLS-SEM, the measurement model was first examined by applying the PLS algorithm technique to confirm the model’s convergent and discriminant validity. Subsequently, the structural model was assessed using a bootstrapping approach to test the hypotheses. Result Descriptive and correlation analysis Table 1 presents the means, standard deviations, and inter-correlations among the key variables of the study. Responsible leadership, gratitude, and organizational identification were positively correlated with OCB. Conversely, no significant correlations were found between the control variables (age, gender, level of education, and academic position) and OCB. Table 1 Mean, standard deviation, and inter-correlations No 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Construct Gender Age Level of education Academic position Responsible leadership Gratitude Organizational identification OCB Mean Standard Deviation 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 − 0.112* − 0.175** − 0.036 − 0.123* − 0.149** − 0.137* 0.007 N/A N/A 0.037 0.372** − 0.068 − 0.114* 0.053 − 0.046 N/A N/A 0.277** − 0.072 − 0.051 − 0.024 − 0.094 N/A N/A − 0.064 − 0.069 0.050 − 0.048 N/A N/A 0.819** 0.352** 0.369** 3.548 0.972 0.456** 0.468** 3.559 1.031 0.478** 3.762 0.781 3.985 0.502 Note. N/A: Not applicable, OCB: Organizational citizenship behavior Luo et al. BMC Psychology (2025) 13:6 Page 8 of 14 Preliminary analysis Measurement model analysis Common method bias (CMB) was assessed due to the self-report nature of the data. Harman’s single-factor test, a statistical method, was employed to detect the presence of CMB. The results from unrotated factor analysis indicated that the first factor accounted for 40.839% of the total variance, which is below the 50% threshold. This suggests that our data does not exhibit significant CMB [94]. Besides, we conducted a full collinearity assessment to detect CMB in PLS-SEM analysis [95]. A variance inflation factor (VIF) exceeding 3.3 would indicate the presence of CMB. Based on the results from the PLS algorithm, the VIF values for responsible leadership, gratitude, organizational identification, and OCB were 2.928, 3.226, 1.159, and 1.148, respectively, indicating that CMB was not present in our data. The measurement model was evaluated using the PLS algorithm technique. This study employed a two-stage approach to estimate the higher-order construct of OCB, which follows a reflective-reflective hierarchical component model (HCM). In the initial phase of the two-stage approach, the focus was on the fundamental elements of OCB in the path model. This involved computing the latent variable scores for the two dimensions of OCB (OCB-I and OCB-O). These dimensions were then utilized as indicators for the higher-order construct in the second stage [96]. The reliability and convergent validity results for each construct of the measurement model are displayed in Table 2. The average variance extracted (AVE) for all key constructs, including the first-order dimensions of OCB, exceeded 0.5. As demonstrated in Table 2, the composite reliability (CR) exceeded 0.7 for all key constructs in this study [96]. Additionally, the values Table 2 Measurement model –convergent validity and internal consistency Variable Responsible Leadership Gratitude Organizational Identification OCB-I (first-order) OCB-O (first-order) OCB (second-order) Indicators RL1 RL2 RL3 RL4 RL5 G1 G2 G3 G4 G5 OI1 OI2 OI3 OI4 OI5 OI6 OCB1 OCB2 OCB3 OCB4 OCB5 OCB6 OCB7 OCB8 OCB9 OCB10 OCB11 OCB12 OCB13 OCB14 OCB-I OCB-O Factor loadings 0.902 0.926 0.877 0.942 0.92 0.959 0.959 0.956 0.943 0.944 0.807 0.876 0.842 0.854 0.921 0.916 0.754 0.851 0.745 0.762 0.852 0.866 0.812 0.584 0.661 0.77 0.731 0.689 0.824 0.814 0.895 0.876 Note. OCB-I = organizational citizenship behavior towards individuals, OCB-O = organizational citizenship behavior towards organization AVE 0.835 Cronbach’s alpha 0.95 Composite reliability (rho_c) 0.962 0.907 0.974 0.98 0.758 0.936 0.949 0.652 0.911 0.918 0.532 0.854 0.879 0.784 0.725 0.879 Luo et al. BMC Psychology (2025) 13:6 Page 9 of 14 Table 3 Discriminant validity based on HTMT Criterion Construct Gratitude OCB Organizational Identification Responsible Leadership Gratitude OCB Organizational Identification 0.567 0.479 0.851 0.597 0.451 0.374 Responsible Leadership Table 4 Results of direct and indirect hypothesis testing Path Beta Standard deviation t- statistics H1 RL -> OCB H2 RL -> G H3 G -> OCB H4 RL -> OI H5 OI -> OCB H6 RL-> G -> OCB H7 RL-> OI-> OCB -0.034 0.820 0.342 0.365 0.353 0.082 0.025 0.082 0.061 0.066 0.068 0.031 0.418 32.974 4.164 6.012 5.306 0.280 0.129 4.151 4.177 p-values Bootstrapping confidence interval 5%LL 95%UL 0.338 -0.169 0.100 0.000 0.775 0.859 0.000 0.203 0.475 0.000 0.265 0.464 0.000 0.245 0.465 0.000 0.167 0.392 0.000 0.083 0.184 Note. RL: responsible leadership, OCB: Organizational citizenship behavior, G: gratitude, OI: organizational identification, LL: Lower level, UL: Upper level of Cronbach’s alpha (α) ranged from 0.725 to 0.974, indicating high internal reliability of all variables. Given that the average variance extracted (AVE) and internal consistency for every construct met the required cut-off values, items with factor loadings between 0.5 and 0.7 were retained, and none of the indicators were removed. To assess the discriminant validity between different indicators, the Heterotrait-Monotrait ratio of correlations (HTMT) values were examined, as presented in Table 3. None of the HTMT correlation values exceeded the threshold value of 0.9 [97]. Consequently, the main latent variables of the study were demonstrated to be distinct concepts. Structural model analysis A bootstrapping approach with 5000 resamples was utilized to evaluate the structural model. In this subsection, the results of direct hypotheses are presented first, followed by the results of indirect hypotheses. Direct hypotheses The results of the direct hypothesis testing are displayed in Table 4. The result shows that responsible leadership is not significantly related to OCB (β=-0.034, t = 0.418, p = 0.338). As a result, H1 is not supported by the data. On the other hand, responsible leadership is positively related to gratitude (β = 0.820, t = 32.974, p < 0.001). Likewise, significant positive relationships are found between gratitude and OCB (β = 0.342, t = 4.164, p < 0.001), responsible leadership and organizational identification (β = 0.365, t = 6.012, p < 0.001), as well as organizational identification and OCB (β = 0.353, t = 5.306, p < 0.001). Hence, H2 to H5 are supported by the data. Indirect hypotheses As shown in Table 4, the results from the evaluation of mediating analyses revealed that responsible leadership indirectly predicts OCB through gratitude (β = 0.280, t = 4.151, p < 0.001) and organizational identification (β = 0.129, t = 4.177, p < 0.001). Hence, H6 and H7 were well-supported by the data. Based on the results, both gratitude and organizational identification were found to fully mediate the indirect effect between the variables since the direct effect (RL --> OCB) was found to be insignificant but the indirect effect appears to be significant. Discussion This study investigated an integrated model that explores the dual mediating mechanism of gratitude and organizational identification in the relationship between responsible leadership and OCB. Surprisingly, the findings revealed that responsible leadership has no direct significant relationship with OCB. This result contradicts previous studies such as Guo and Su [98] and Thakur and Sharma [24] while aligning with findings from Freire and Gonçalves [26] and Khanam and Tarab [25]. The inconsistency in results could be attributed to various contextual factors that potentially alter the strength of the relationship. These factors include organizational culture, industry norms, and individual differences among employees and occupations [99]. For example, the study by Guo and Su [98] was conducted in China, with data collected from private sector companies and constructs measured using Chinese scales. Conversely, Freire and Gonçalves [26] examined the framework by collecting data from frontline employees in Portuguese high-end hotels, with item scales adapted from a Western context. Therefore, context specificity and the choice of Luo et al. BMC Psychology (2025) 13:6 scales have a certain impact on the relationship between responsible leadership and OCB. Besides, our findings confirm that gratitude significantly mediates the relationship between responsible leadership and OCB. As hypothesized, responsible leaders consistently demonstrate moral and ethical conduct, taking into consideration the interests of all stakeholders [4, 5, 61]. These positive leadership behaviors are often perceived by employees as genuine concern for their well-being [100]. Consequently, employees will likely develop a sense of gratitude towards the leader. Employees who experience gratitude in the workplace are inclined to engage in prosocial behaviors, including OCB [58]. According to Affective Events Theory, the relationship between employees’ perception of trust in their supervisor and their work engagement is mediated by gratitude [59]. Similarly, responsible leadership, which often exhibits ethical and considerate behavior, can evoke employees’ gratitude, thereby promoting OCB [27, 101]. Lastly, this study’s findings further confirm that the relationship between responsible leadership and OCB is significantly mediated by organizational identification. This finding is supported by Freire and Gonçalves [26] in the context of the hospitality industry. Responsible leadership demonstrates concern, care, and attention toward employees, fosters reliable relationships with employees [61], and engages in socially responsible organizational activities [75, 76], thereby increasing organizational identification among employees [36]. When employees have a high level of organizational identification, they tend to feel a strong connection and alignment with their organization and strive for its success [79]. Implications Theoretical implications This research contributes significantly to the understanding of organizational behavior by examining leadership, gratitude organizational identification, and OCB. First and foremost, the insignificant relationship between responsible leadership and OCB in higher educational institutions is consistent with findings from previous studies conducted in service industries such as hotel and healthcare sectors [25, 26]. In contrast, research conducted in pharmaceutical firms has shown a different relationship [24]. This variation indicates that the link between responsible leadership and OCB may be highly context-dependent, determined by unique organizational characteristics and sector-specific norms. This context-specific gap suggests that responsible leadership, while valuable, may not drive OCB directly in higher education as it does in some other sectors. Instead, this leadership style may related to OCB indirectly by fostering an environment where gratitude and organizational identification serve as mediating mechanisms. Unlike Page 10 of 14 more hierarchical or commercially focused industries, higher education emphasizes autonomy, intellectual freedom, and individual initiative among employees. Consequently, responsible leaders in this context can better trigger the desire of academic staff to engage in OCB by creating an environment that promotes gratitude and organizational identification within the institutions. Secondly, this study fills a crucial gap in the literature by examining the mediating role of gratitude between responsible leadership and OCB. This relationship is grounded in Affective Events Theory [27], which suggests that leaders’ behavior can determine subordinates’ emotional responses and subsequently shape their work attitudes and behavior. In this regard, our research sheds light on the role of responsible leadership in fostering feelings of gratitude, which consequently drives OCB among academic staff. Previous research has demonstrated that servant leadership [31, 32] and leaders’ forgiveness [35] evoke feelings of gratitude among employees, leading to specific behavioral outcomes. Our study emphasized that gratitude is a key mechanism connecting responsible leadership and employees’ voluntary behavior. By demonstrating that responsible leadership promotes gratitude, which in turn enhances OCB among academic staff, our findings contribute to a theoretical understanding of how positive emotions function within a higher educational context to encourage desired behaviors. This insight encourages further exploration of responsible leadership as a strategic approach to fostering gratitude and enhancing OCB, especially in sectors where ethical conduct and employee well-being are highly valued. Another significant theoretical contribution is demonstrated by confirming that organizational identification plays a crucial mediating role in the relationship between responsible leadership and OCB in the higher education context. This enriched the existing literature by extending the contextual applicability, as empirical evidence on this mediating mechanism has only been testified in the hospitality sector [26]. By establishing that responsible leadership can enhance organizational identification, which subsequently fosters OCB among academic staff in higher education, our study delivers valuable insights into how responsible leadership operates in this unique setting. Practical implications This study highlights the crucial role of responsible leadership in fostering feelings of gratitude and organizational identification among employees, ultimately encouraging them to engage in OCB. These findings offer important practical insights for universities, particularly in shaping their human resource practices. University administrators should consider these results when making decisions Luo et al. BMC Psychology (2025) 13:6 related to leadership recruitment, development, and performance evaluation. In higher education, it is essential to strategically recruit leaders who not only have the necessary academic and administrative qualifications but also demonstrate strong ethical standards and moral integrity. This can be achieved by incorporating personality assessments and performance simulation tests during the recruitment process to identify candidates who exhibit responsibility, empathy, and fairness. Additionally, integrating OCB-related criteria into faculty performance appraisals can encourage staff to engage more actively in behaviors that benefit the institution beyond their formal job descriptions. To further promote OCB, universities should foster a supportive and collaborative environment through initiatives such as team-building activities and professional development programs. Furthermore, numerous enterprises advocate for a culture of gratitude and emphasize the role of employee gratitude. Gratitude is recognized as a valuable positive emotion that can lead to several beneficial effects on employees, their interpersonal relationships, and the organization as a whole [30]. The findings of this study indicate that continuously improving the quality of responsible leadership can stimulate employee gratitude. For example, in the absence of gratitude, employees might not fully appreciate their colleagues’ efforts and the support from the organization, leading to these contributions being undervalued or taken for granted. In the context of higher education, it is crucial for university leaders to actively cultivate a culture of gratitude by demonstrating genuine care for the well-being of faculty and staff. This can be achieved through consistent, responsible leadership practices that acknowledge and appreciate employees’ contributions, both individually and as a group. By raising awareness of gratitude and encouraging behaviors that recognize and celebrate the efforts of others, university leaders can foster a more positive and supportive work environment. Finally, responsible leaders shape the behavior of their followers by promoting the organization’s mission, values, culture, and ethical standards. Organizational identification enhances the bonding between individuals and their organization, leading to the formation of strong emotional and affective attachments among academic staff to both their university and work roles. Therefore, the mediating role of organizational identification suggests that university administrations should recruit individuals whose personal beliefs closely align with those of the educational institution. Additionally, university leaders should actively demonstrate socially responsible behaviors, such as ethical decision-making, transparency, and a commitment to social good, to serve as role models for their staff. When leaders demonstrate these values, they encourage employees to internalize the Page 11 of 14 institution’s mission, thereby strengthening their emotional attachment to the university and enhancing overall organizational cohesion. This sense of identification can lead to greater employee engagement, improved morale, and a more collaborative and productive academic environment. Limitations and future research Our study has several limitations. Firstly, this study employs a cross-sectional design, which limits the ability to establish causality. Longitudinal design, on the other hand, is a better approach that can be employed by future researchers to effectively determine the cause-andeffect relationship among these variables by tracking the changes over time. As such, future researchers can further evaluate the current research model with a longitudinal research design to verify the findings of this study, ultimately improving our understanding of the interactions between the variables. Secondly, the data were collected via a self-reported survey, which may introduce potential CMB. While Harman’s single-factor test and full collinearity assessment were performed, this does not guarantee the complete elimination of bias effects. Future studies could gather data on predictors and outcome variables separately from employees and leaders, which is regarded as a better way to mitigate or evade CMB. Thirdly, this research solely focused on a single leadership style, namely responsible leadership, in evaluating its interplay with gratitude, organizational identification, and OCB. Future research can further enrich the present research framework by incorporating additional leadership styles, such as charismatic and spiritual leadership, to predict the outcomes. The extension of the current research model facilitates future research to make meaningful comparisons between different leadership styles and their respective outcomes, especially in a longitudinal research setting. Finally, our study focused on academics in higher education institutions in China. It is essential to recognize that employees from diverse cultural backgrounds may hold distinct perspectives. Therefore, future research might consider including employees from different cultural backgrounds in their study, such as those from Western countries, as well as from multi-ethnic societies like Malaysia, to enhance the generalizability or comparability of our findings. Conclusion This study developed a research framework based on Affective Event Theory and Social Identity Theory to investigate the relationships among responsible leadership, gratitude, organizational identification, and OCB. The findings highlight that gratitude and organizational Luo et al. BMC Psychology (2025) 13:6 identification among academic staff are key mediators linking responsible leadership to OCB. Our study enhances the understanding by showing the significance of emotional dynamics in shaping workplace behaviors. As such, higher education institutions should prioritize cultivating responsible leadership to enhance employee gratitude and organizational identification, ultimately benefiting both individuals and the organization. Abbreviations OCBOrganizational Citizenship Behavior OCB-IOrganizational citizenship behavior towards individuals OCB-OOrganizational citizenship behavior towards the organization AETAffective Events Theory SITSocial Identity Theory PLS-SEMPartial Least Squares-Structural Equation Modelling CMBCommon method bias VIFVariance inflation factor AVEAverage variance extracted CRComposite reliability HTMTHeterotrait-Monotrait ratio of correlations Acknowledgements The authors would like to extend their heartfelt gratitude and appreciation to all the participants of this study. Author contributions Luo, J. was responsible for the design of the study, literature review, data collection, data analysis, and preparing the manuscript. L.-P. Ng and Y.-O. Choong provided supervision and guidance, as well as reviewed and edited the paper. All authors reviewed the final manuscript. Funding This work was supported by the China Scholarship Council “National and Regional Research Talent Support Program [2022] 708” [CSC NO. 202208520022]. Page 12 of 14 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. Data availability The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available because they are required to be kept confidential, which is requested by the third party, but they are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. 17. Declarations 19. Ethical approval This study received ethical approval from the Scientific and Ethical Review Committee of Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman (Reference No. U/ SERC/306/2023). All procedures performed in the study that involved human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. 18. 20. 21. Consent for publication Not applicable. 22. Competing interests The authors declare no competing interests. 23. Received: 3 August 2024 / Accepted: 30 December 2024 24. 25. References 1. Compagnucci L, Spigarelli F. The third mission of the university: a systematic literature review on potentials and constraints. Technol Forecast Soc Change. 2020;161:120284. 26. Hu J, Liu H, Chen Y, Qin J. Strategic planning and the stratification of Chinese higher education institutions. Int J Educ Dev. 2018;63:36–43. Bodenhorn T, Burns JP, Palmer M, Change. Contradiction and the state: higher education in Greater China. China Q. 2020;244:903–19. Maak T, Pless NM. Responsible leadership in a stakeholder society – A relational perspective. J Bus Ethics. 2006;66:99–115. Voegtlin C, Patzer M, Scherer AG. Responsible leadership in global business: a new approach to leadership and its multi-level outcomes. J Bus Ethics. 2012;105:1–16. Haider SA, Akbar A, Tehseen S, Poulova P, Jaleel F. The impact of responsible leadership on knowledge sharing behavior through the mediating role of person–organization fit and moderating role of higher educational institute culture. J Innov Knowl. 2022;7:100265. Mousa M. Organizational inclusion and academics’ psychological contract: can responsible leadership mediate the relationship? Equal Divers Incl Int J. 2019;ahead-of-print. Kyambade M, Namuddu R, Mugambwa J, Namatovu A. I can’t express myself at work: encouraging socially responsible leadership and psychological safety in higher education setting. Cogent Educ. 2024;11:2373560. Li M, Yang F, Akhtar MW. Responsible leadership effect on career success: the role of work engagement and self-enhancement motives in the education sector. Front Psychol. 2022;13:888386. De Souza-Daw T, Ross R. Fraud in higher education: a system for detection and prevention. J Eng Des Technol. 2023;21:637–54. Liu A. Why are Chinese university faculty reluctant to participate in school governance based on the theory of organizational citizenship behavior. High Educ Explor. 2020;:30–5. Oplatka I. Irresponsible leadership and unethical practices in schools: a conceptual framework of the dark side of educational leadership. In: Normore A, Tony H, Brooks JS, editors. Advances in Educational Administration. Emerald Group Publishing Limited; 2016. pp. 1–18. Carini C, Rocca L, Veneziani M, Teodori C. Sustainability regulation and global corporate citizenship: a lesson (already) learned? Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag. 2021;28:116–26. Su F, Wood M. What makes a good university lecturer? Students’ perceptions of teaching excellence. J Appl Res High Educ. 2012;4:142–55. Wan CD, Sirat M, Razak DA. Academic governance and leadership in Malaysia: examining the national higher education strategic initiatives. J Int Comp Educ JICE. 2020;91–102. Alfagira Sgdwar, Zumrah A, Noor ARB, Rahman KBM. OBA. Investigating the factors influencing academic staff performance: a conceptual approach. 2017. https://doi.org/10.21276/sjebm.2017.4.11.13 Guo L, Huang J, Zhang Y. Education development in China: education return, quality, and equity. Sustainability. 2019;11:3750. Qiu S, Alizadeh A, Dooley LM, Zhang R. The effects of authentic leadership on trust in leaders, organizational citizenship behavior, and service quality in the Chinese hospitality industry. J Hosp Tour Manag. 2019;40:77–87. Butt A, Lodhi RN, Shahzad MK. Staff retention: a factor of sustainable competitive advantage in the higher education sector of Pakistan. Stud High Educ. 2020;45:1584–604. Donglong Z, Taejun C, Julie A, Sanghun L. The structural relationship between organizational justice and organizational citizenship behavior in university faculty in China: the mediating effect of organizational commitment. Asia Pac Educ Rev. 2020;21:167–79. Oplatka I. Organizational citizenship behavior in teaching: the consequences for teachers, pupils, and the school. Int J Educ Manag. 2009;23:375–89. Haque A, Fernando M, Caputi P. Responsible leadership and employee outcomes: a systematic literature review, integration and propositions. Asia-Pac J Bus Adm. 2021;13:383–408. Akbari M, Hemmatinejad M, Azimian O, Hosseinzadeh A. The impact of responsible leadership on organizational citizenship behavior through the mediating role of organizational justice and organizational commitment (case study: Guilan Red Crescent Society employees). Biannu J Psychol Res Manag. 2021;6:33–71. Thakur DJ, Sharma D. Responsible leadership style and organizational citizenship behavior: a relationship study. Pac Bus Rev Int. 2019;12:21–9. Khanam Z, Tarab S. A moderated-mediation model of the relationship between responsible leadership, citizenship behavior and patient satisfaction. IIM Ranchi J Manag Stud. 2023;2:114–34. Freire C, Gonçalves J. The relationship between responsible leadership and organizational citizenship behavior in the hospitality industry. Sustainability. 2021;13:4705. Luo et al. BMC Psychology (2025) 13:6 27. Weiss HM, Cropanzano R. Affective events theory. Res Organ Behav. 1996;18:1–74. 28. Bartlett MY, DeSteno D. Gratitude and prosocial behavior: helping when it costs you. Psychol Sci. 2006;17:319–25. 29. Emmons RA, McCullough ME, Tsang J-A. The assessment of gratitude. 2003. 30. Fehr R, Fulmer A, Awtrey E, Miller JA. The grateful workplace: a multilevel model of gratitude in organizations. Acad Manage Rev. 2017;42:361–81. 31. Baykal E, Zehi̇R C, Köle M. Effects of servant leadership on gratitude, empowerment, innovativeness and performance: Turkey example. J Econ Cult Soc. 2018;:29–52. 32. Sun J, Liden RC, Ouyang L. Are servant leaders appreciated? An investigation of how relational attributions influence employee feelings of gratitude and prosocial behaviors. J Organ Behav. 2019;40:528–40. 33. Xia J, Xu H, Xie L. Inclusive leadership and employee involvement in proactive behavior at the workplace: the mediating role of gratitude. Balt J Manag. 2024;19:200–17. 34. Ashfaq F, Abid G, Ilyas S, Elahi AR. Sustainable Leadership and Work Engagement: exploring sequential mediation of Organizational Support and Gratitude. Public Organ Rev. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11115-024-00778-w. 35. Lu L, Huang Y, Luo J. Leader forgiveness and employee’s unethical proorganizational behavior: the roles of gratitude and moral identity. Front Psychol. 2021;12. 36. Gomes JFS, Marques T, Cabral C. Responsible leadership, organizational commitment, and work engagement: the mediator role of organizational identification. Nonprofit Manag Leadersh. 2022;33:89–108. 37. Batool S, Izwar Ibrahim H, Adeel A. How responsible leadership pays off: role of organizational identification and organizational culture for creative idea sharing. Sustain Technol Entrep. 2024;3:100057. 38. Van Knippenberg D, Hogg MA. A social identity model of leadership effectiveness in organizations. Res Organ Behav. 2003;25:243–95. 39. Stone-Johnson C. Responsible Leadership. Educ Adm Q. 2014;50:645–74. 40. Kia N, Halvorsen B, Bartram T. Ethical leadership and employee in-role performance: the mediating roles of organisational identification, customer orientation, service climate, and ethical climate. Pers Rev. 2019;48:1716–33. 41. Han Z, Wang D, Ni M. A review of the responsible leadership research and its prospects from the vision of China. Acad J Bus Manag. 2022;4:27–37. 42. Tajfel H, Turner JC. The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. Political psychology. Psychology; 2004. pp. 276–93. 43. Tajfel H. Social categorization, social identity and social comparison. Differ Soc Group. 1978;:61–76. 44. Glavas A, Godwin LN. Is the perception of ‘goodness’ good enough? Exploring the relationship between perceived corporate social responsibility and employee organizational identification. J Bus Ethics. 2013;114:15–27. 45. Mesmer-Magnus JR, Asencio R, Seely PW, DeChurch LA. How organizational identity affects team functioning: the identity instrumentality hypothesis. J Manag. 2018;44:1530–50. 46. Ashforth BE, Rogers KM, Corley KG. Identity in organizations: exploring crosslevel dynamics. Organ Sci. 2011;22:1144–56. 47. Organ DW. Organizational citizenship behavior: the good soldier syndrome. Lexington, MA: Lexington.; 1988. 48. Williams LJ, Anderson SE. Job satisfaction and organizational commitment as predictors of organizational citizenship and in-role behaviors. J Manag. 1991;17:601–17. 49. DiPaola MF, Hoy WK. Organizational citizenship of faculty and achievement of high school students. High Sch J. 2005;88:35–44. 50. Aboramadan M, Dahleez KA, Farao C. Inclusive leadership and extra-role behaviors in higher education: does organizational learning mediate the relationship? Int J Educ Manag. 2021;36:397–418. 51. Ho HX, Le ANH. Investigating the relationship between benevolent leadership and the organizational citizenship behaviour of academic staff: the mediating role of leader-member exchange. Manag Educ. 2023;37:74–84. 52. Shareef RA, Atan T. The influence of ethical leadership on academic employees’ organizational citizenship behavior and turnover intention: mediating role of intrinsic motivation. Manag Decis. 2019;57:583–605. 53. Taamneh M, Aljawarneh N, Al-Okaily M, Taamneh A, Al-Oqaily A. The impact of ethical leadership on organizational citizenship behavior in higher education: the contingent role of organizational justice. Cogent Bus Manag. 2024;11:2294834. 54. Ghavifekr S, Adewale AS. Can change leadership impact on staff organizational citizenship behavior? A scenario from Malaysia. High Educ Eval Dev. 2019;13:65–81. Page 13 of 14 55. Al-Mamary YHS. The impact of transformational leadership on organizational citizenship behaviour: evidence from Malaysian higher education context. Hum Syst Manag. 2021;40:737–49. 56. Mahembe B, Engelbrecht AS. The relationship between servant leadership, organisational citizenship behaviour and team effectiveness. SA J Ind Psychol. 2014;40:10. 57. De Ruiter M, Schaveling J, Ciulla JB, Nijhof A. Leadership and the creation of corporate social responsibility: an introduction to the special issue. J Bus Ethics. 2018;151:871–4. 58. Spence JR, Brown DJ, Keeping LM, Lian H. Helpful today, but not tomorrow? Feeling grateful as a predictor of daily organizational citizenship behaviors. Pers Psychol. 2014;67:705–38. 59. Wang C. Antecedent, influence and boundary conditions of state gratitude. China Acad J. 2019;16:1640–9. 60. Guzzo RF, Wang X, Abbott J. Corporate social responsibility and individual outcomes: the mediating role of gratitude and compassion at work. Cornell Hosp Q. 2022;63:350–68. 61. Stahl GK, Sully de Luque M. Antecedents of responsible leader behavior: a research synthesis, conceptual framework, and agenda for future research. Acad Manag Perspect. 2014;28:235–54. 62. Voegtlin C, Greenwood M. Corporate social responsibility and human resource management: a systematic review and conceptual analysis. Hum Resour Manag Rev. 2016;26:181–97. 63. Kim YJ, Van Dyne L, Lee SM. A dyadic model of motives, pride, gratitude, and helping. J Organ Behav. 2018;39:1367–82. 64. Ford MT, Wang Y, Jin J, Eisenberger R. Chronic and episodic anger and gratitude toward the organization: relationships with organizational and supervisor supportiveness and extrarole behavior. J Occup Health Psychol. 2018;23:175–87. 65. Dutton JE, Dukerich JM, Harquail CV. Organizational images and member identification. Adm Sci Q. 1994;:239–63. 66. Mael F, Ashforth BE. Alumni and their alma mater: a partial test of the reformulated model of organizational identification. J Organ Behav. 1992;13:103–23. 67. Ashforth BE, Mael F. Social identity theory and the organization. Acad Manage Rev. 1989;14:20. 68. Hogg MA, van Knippenberg D. Social identity and leadership processes in groups. Adv Exp Soc Psychol. 2003;35:1–52. 69. Walumbwa FO, Mayer DM, Wang P, Wang H, Workman K, Christensen AL. Linking ethical leadership to employee performance: the roles of leader– member exchange, self-efficacy, and organizational identification. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 2011;115:204–13. 70. Buil I, Martínez E, Matute J. Transformational leadership and employee performance: the role of identification, engagement and proactive personality. Int J Hosp Manag. 2019;77:64–75. 71. Herman HM, Chiu WC. Transformational leadership and job performance: a social identity perspective. J Bus Res. 2014;67:2827–35. 72. Haque A, Fernando M, Caputi P. The relationship between responsible leadership and organisational commitment and the mediating effect of employee turnover intentions: an empirical study with Australian employees. J Bus Ethics. 2019;156:759–74. 73. Haque A, Fernando M, Caputi P. How is responsible leadership related to the three-component model of organisational commitment? Int J Prod Perform Manag. 2021;70:1137–61. 74. He J, Morrison AM, Zhang H. Being sustainable: the three-way interactive effects of CSR, green human resource management, and responsible leadership on employee green behavior and task performance. Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag. 2021;28:1043–54. 75. Newman A, Miao Q, Hofman PS, Zhu CJ. The impact of socially responsible human resource management on employees’ organizational citizenship behaviour: the mediating role of organizational identification. Int J Hum Resour Manag. 2016;27:440–55. 76. De Roeck K, El Akremi A, Swaen V. Consistency matters! How and when does corporate social responsibility affect employees’ organizational identification? J Manag Stud. 2016;53:1141–68. 77. Doh JP, Quigley NR. Responsible leadership and stakeholder management: influence pathways and organizational outcomes. Acad Manag Perspect. 2014;28:255–74. 78. Blader S, Patil S, Packer D. Organizational identification and workplace behavior: more than meets the eye. Res Organ Behav. 2017;37. 79. Bullis CA, Tompkins PK. The forest ranger revisited: a study of control practices and identification. Commun Monogr. 1989;56:287–306. Luo et al. BMC Psychology (2025) 13:6 80. Riketta M. Organizational identification: a meta-analysis. J Vocat Behav. 2005;66:358–84. 81. Scott CR, Stephens KK. It depends on who you’re talking to… predictors and outcomes of situated measures of organizational identification. West J Commun. 2009;73:370–94. 82. Ministry of Education China. Number of higher education institutions. http:// www.moe.gov.cn/jyb_sjzl/moe_560/2021/gedi/202301/t20230117_1039557 .html (2021). Accessed 15 May 2023. 83. Voegtlin C. Development of a scale measuring discursive responsible leadership. Responsible Leadersh. 2011;:57–73. 84. Afsar B, Maqsoom A, Shahjehan A, Afridi SA, Nawaz A, Fazliani H. Responsible leadership and employee’s proenvironmental behavior: the role of organizational commitment, green shared vision, and internal environmental locus of control. Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag. 2020;27:297–312. 85. Dong W, Zhong L. Responsible leadership fuels innovative behavior: the mediating roles of socially responsible human resource management and organizational pride. Front Psychol. 2021;12:5885. 86. Xiao X, Zhou Z, Yang F, Qi H. Embracing responsible leadership and enhancing organizational citizenship behavior for the environment: a social identity perspective. Front Psychol. 2021;12:632629. 87. Tan LP, Yap CS, Choong YO, Choe KL, Rungruang P, Li Z. Ethical leadership, perceived organizational support and citizenship behaviors: the moderating role of ethnic dissimilarity. Leadersh Organ Dev J. 2019;40:877–97. 88. Teng C-C, Lu ACC, Huang Z-Y, Fang C-H. Ethical work climate, organizational identification, leader-member-exchange (LMX) and organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) a study of three star hotels in Taiwan. Int J Contemp Hosp Manag. 2020;32:212–29. 89. Yang C, Chen Y, Chen A, Ahmed SJ. The integrated effects of leader–member exchange social comparison on job performance and OCB in the Chinese context. Front Psychol. 2023;14. 90. Brislin RW. The wording and translation of research instruments. Field Methods Cross-Cult Res. 1986;:137–64. 91. Hair J, Alamer A. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) in second language and education research: guidelines using an applied example. Res Methods Appl Linguist. 2022;1:100027. Page 14 of 14 92. Dash G, Paul J. CB-SEM vs PLS-SEM methods for research in social sciences and technology forecasting. Technol Forecast Soc Change. 2021;173:121092. 93. Hair J, Risher JJ, Sarstedt M, Ringle CM. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur Bus Rev. 2019;31:2–24. 94. Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee J-Y, Podsakoff NP. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol. 2003;88:879–903. 95. Kock N. Common Method Bias in PLS-SEM: a full collinearity Assessment Approach. Int J E-Collab. 2015;11:1–10. 96. Sarstedt M, Hair JF, Cheah J-H, Becker J-M, Ringle CM. How to specify, estimate, and validate higher-order constructs in pls-sem. Australas Mark J. 2019;27:197–211. 97. Gold AH, Malhotra A, Segars AH. Knowledge management: an organizational capabilities perspective. J Manag Inf Syst. 2001;18:185–214. 98. Guo YX, Su Y. The double-edged sword effect of responsible leadership on subordianates′ organizational citizenship behavior. Res Econ Manag. 2018;39:90–102. 99. Rudolph CW, Katz IM, Lavigne KN, Zacher H. Job crafting: a meta-analysis of relationships with individual differences, job characteristics, and work outcomes. J Vocat Behav. 2017;102:112–38. 100. Kelemen TK, Matthews SH, Breevaart K. Leading day-to-day: a review of the daily causes and consequences of leadership behaviors. Leadersh Q. 2020;31:101344. 101. Voegtlin C, Frisch C, Walther A, Schwab P. Theoretical development and empirical examination of a three-roles model of responsible leadership. J Bus Ethics. 2020;167:411–31. Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.