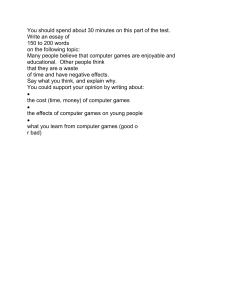

How to WRITE THE PERFECT PERSONAL ESSAY for U.S. colleges Contents 01 02 03 04 05 06 Introduction Making your essay work Writing crash course 101 The purpose of the essay A checklist: Essay types Finding your voice: Basic grammar and style Self-edit your work Take your time What to avoid in your essay Essay Case Studies Final Thoughts Six examples of essays used in successful applications Closing statements Important things to keep in mind when writing your essay 2 01 Introduction The US college application process is stressful for anyone. But it’s especially stressful if you don’t know what your dream school is looking for. Elite colleges recognise that they are responsible for making you feel the overwhelming pressure of being beyond perfect. Are your scores high enough? Are your extracurriculars diverse enough? Are your grades good enough? While academics are still very important, many US colleges now focus on a more balanced application process. They emphasize what you as an individual have to offer to their school. The insane levels of competition to get into elite US colleges serve only to heighten those anxieties. Maybe you’ve helplessly wondered to yourself, “What chance do I have when Ivy League schools accept 8.5% of applicants on average?” You’ve probably concluded that if you don’t have a perfect 1600 or 36 ACT and perfect extracurriculars, then you don’t have a chance, right? They don’t just care about your scores or your lists of accomplishments. They care about what makes you tick, what makes you think, what makes you cry or celebrate. They care about who you are. The best way to communicate who you are in your application is through your personal essay. Wrong. As you probably already know, you won’t get accepted to college on the strength of your essay alone. The entire application process is changing. But it is also the only way that your voice can be heard by admissions officers. Without it, all colleges have to help them make their decisions are your numbers - numbers of activities, numbers of A’s, and SAT numbers, to name a few. These application criteria are the metrics used to compare you to other applicants. The essay gives those metrics colour. It can also make a significant difference to your application at highly-competitive schools, particularly if you fall just short of the expected admissions metrics or if your metrics align with those of another applicant. A great essay might leapfrog you over other candidates with superior test scores and grades because it shows, for example, your strong moral compass and leadership abilities, making you ultimately more attractive than someone with a higher SAT score than you have. The essay can also help colleges understand why you’ve chosen to apply to their school and why you’d make a great addition on campus. Accordingly, this eBook will cover the most important factors in a college essay, including: • What colleges look for when reading personal statements • Crafting your own personal statement • Becoming a better writer • What successful essays look like And finally, we’ll give you six – yes, SIX – unique personal statements from successful applicants. All of these examples are originals from our archives, which haven’t been shared online before. The guidance in this eBook will work to make you a much more competitive applicant, as long as you take our advice to heart and don’t forget to put in plenty of work on your own! In this way, you can get a leg-up on being accepted to your dream school. 3 02 Making your essay work Before you start hammering away on the keyboard about the time that you saved a kitten from a tree, you need to understand what makes your essay work. Work, in this instance, means an essay that meets, or even exceeds, the expectations of the admissions officer. So how do we help you make your essay work? 4 Yale’s admission officer Current Harvard student Top Crimson admissions consultant Here’s what Yale’s admissions officer has to say on this subject: A current Harvard student emphasized other essential aspects of the essay: “We know that no one can fit an entire life story into two brief essays, and we don’t expect you to try. Pick a topic that will give us an idea of who you are. It doesn’t matter which topic you choose, as long as it is meaningful to you. We have read wonderful essays on common topics and weak essays on highly unusual ones. Your perspective – the lens through which you view your topic – is far more important than the specific topic itself. “Good writing is essential. A wellwritten essay can take a mediocre topic and turn it into something compelling. It doesn’t have to be written like Hemingway either – lyrical, playful, or artistic writing is great, but not necessary. Don’t forget to include the key takeaways from whatever experience you write about – the better the insight, the better the admissions officer’s perception of the applicant will be. Finally, make sure you justify your application to some degree. Does your essay clarify why you want to go to college? And what you’ll contribute to the campus when you arrive?” And finally, a quotation from a top admissions consultant at Crimson Education, who has helped students gain admission to Harvard, Stanford, and MIT: In the past, students have written about family situations, ethnicity or culture, school or community events to which they have had strong reactions, people who have influenced them, significant experiences, intellectual interests, personal aspirations, or – more generally – topics that spring from the life of the imagination.” “Exhibiting personal growth is a key element of a great essay. An interesting personal experience is a solid starting point, but without bringing the narrative to a fulfilling conclusion – a lesson learned, improvements made, a mission to do better in the future or help improve others – the essay will seem incomplete.” 31,445 Yale applicants 1,373 Admissions 39,041 Harvard applicants 2,106 Admissions 5 Key indicators Soft indicators Let’s unpack These comments reveal three key indicators of a strong essay: But we also found four soft indicators that you won’t see quoted from any admissions officer. These are features of an application that admissions officers seek out in general – but you can include them in the essay to give your application an extra edge. What have we got here? They are: What do they mean exactly and how can you demonstrate them in your essay? They are: 1. Individuality, relevance, and novelty when choosing your topic 2. Insight, reflection, and personal growth from the central theme or experience 3. Careful, compelling, and wellconstructed writing 1. Intellectual curiosity 2. Passionate involvement in a certain area, or a special talent, and how it has impacted your worldview 3. What you’ll take from and bring to your college campus (especially in supplementary essays) 4. Your most important relationships – with a parent, a sibling, your religion, or your culture It’s a checklist for writing a strong personal essay. So, let’s put a little more meat on the bones of these indicators. 6 Key Indicator #1 Individuality, relevance, and novelty when choosing your topic. “ ” Remember: Setup, Conflict, Resolution. What life experiences up to this point have had a profound impact on you? What have you done, seen, read, or created that changed how you see the world? The conflict delves into the story’s point of inflection, when things begin changing because of some central challenge or event. Character development is essential here. The experience you choose to write about must be relevant to how you have become the person you are today, and it should give your reader an idea about what matters most to you. What relationships in your life have most powerfully shaped you? Your topic will be engaging to the reader if it’s engaging to you. The story’s resolution brings everything to a close, but it doesn’t have to be conclusive, considering you are trying to take the next steps of your journey in college! You should aim to provide a reader with a solution to the conflict or challenge you described, and some sort of closure or vision for the future. Your essay can be a narrative – it can tell a meaningful story. In fact, having a clear storyline can be very valuable. Remember the classic narrative form: setup, conflict, and resolution. • A defining experience you’ve had at home, at school, or abroad • How you learned some new truth about the world • A time when you failed miserably and what it meant to you • A lesson taught to you by a family member or member of the community The setup introduces the main characters and foreshadows the upcoming conflict or main issue – this could be a point of growth for you. With that in mind, your essay shouldn’t read like a résumé; it should read like a person wrote it. Show what you’ve learned by describing your insights. Don’t tell what you’ve done by listing events in an aimless sequence. You might write a story about: 7 Key Indicator #2 Insight, reflection, and personal growth from the central theme or experience. You need more than a compelling topic. You need more than a description of an experience. You need to demonstrate your ability to gain insight into your experience; to learn, grow, and reflect. “ ” Show your understanding, don’t retell an event. An event in your life may have been very significant to you, but if you haven’t learned anything about yourself or the world, then the experience will come across as meaningless. The construction of an insight is fairly straightforward. Your essay should demonstrate a clear progression of past, present, and future. In the past, I had this experience. In the present I now have this insight, and in the future I want to do that differently. This is in line with the storytelling framework we established above. It is crucial that your insights be appropriate in scope. Your insights should be personal, reflective, and specific. No one expects you to suddenly understand mankind or the meaning of life – “now I see that all people are connected” or some other cliché – but rather, what you have learned about yourself, your family, or your neighborhood. to overcome a childhood stutter, or the understanding that you can use your struggle to teach and help others in the community, or the awakening that came from finding parts of the character in yourself. It is also important to illustrate how your topic – an experience, a relationship, or something else – has driven your personal growth. What personal growth really translates to is gaining perspective: contextualizing yourself and your experiences in the world around you, how your actions impact others, and how your experiences contribute to a richer understanding of who you are. With that in mind, consider this: the topic of the essay isn’t as important as the insight you draw from it. The essay can be about shopping at a supermarket, but if it tells your story, or it reveals something profound about your character, then it’s a successful essay. Remember that this essay is about you and what you’ve experienced, not about the experience itself. For example, an essay about a first-place performance of a Shakespearean monologue should not focus on the performance itself, or the accolade, or what the judges thought. Instead, it should prioritize the struggle 8 Key Indicator #3 Careful, compelling, and wellconstructed writing. Your writing needs to be clean. “ ” Give meaning to every line and stay on topic. You need to clearly communicate the main idea of your essay. Whatever your key insight or big takeaway is, your writing must be clear and organized to get the idea across. Each sentence must have clear meaning and should clearly relate to your topic. Do not generalize the thoughts or feelings that you describe: you should use detailed descriptions. Do not vaguely mention your experience – “the Shakespeare competition made me appreciate theater”. Do specifically describe your insights – “the competition made me realize that theater gives me more than a basic understanding of others; the constant character work has pointed me towards a deeper familiarity with my own character, and how I relate to others”. Your essay should stay on-topic throughout. A well-structured essay means a logical progression of descriptions, ideas, and conclusions. Do the work of organizing for your reader – do not make them wonder how one paragraph relates to another. Your essay should not be confusing to read. Your writing also needs to be checked perfectly for spelling and grammar. This means no typos, appropriate use of syntax, and correct grammar. Your essay should clearly communicate that it is a product that you have put significant time and thought into. It should not appear sloppy, careless, or thrown together, because the reader will project those qualities onto you. 9 Supplementary essay types Usually, each college you apply to requires you to submit one or two additional essays on top of the Common App that specifically focus on their school: these are called supplements. There are three general types of prompts for supplement essays, each of which requires a different approach. to write about one of the stronger aspects of your application. This topic is an opportunity to discuss your insights into an experience or event in your life different from the one you described in your Common App. Focus on one or two of your central values or goals. Do not try to tell your entire life story. Be personal and vulnerable. No clichés. The three types of essay: Here’s an example. 1. Be wary of the open-ended prompt since it may be difficult to cover cohesively. You can’t describe everything about yourself that might “contribute to our community” in one essay, but you can certainly talk about one thing in great depth. Make sure to stay structured and on-topic. The ‘you’ essay: this essay asks you to tell the university about yourself. The college wants to know you better and understand how your specific characteristics and experiences align with the college’s culture and values. Example: “The University of Texas at Austin values a diversity of interests. What contributions might you make to our community outside of academic excellence?” This is your chance to distinguish yourself from other applicants. Since there are no specific guidelines, you can choose 2. The ‘why us?’ essay (only for supplemental essays): this essay asks why you’ve chosen to apply to this particular college and what your goals are if you study at this campus. Example: “How did you become interested in Swarthmore?” Whereas the previous essay type gave you an opportunity to speak broadly about your abilities, this topic provides a chance to narrow in on why and how this college aligns with your path. It also allows you to show off your specific knowledge of the college, and why its majors, programs, and campus culture fit your interests perfectly. Make sure you thoroughly research this section. Factual blunders will almost surely eliminate you. It can be difficult to align your unique qualities with generic university requirements, so make sure to be specific. If possible, visit the college in person to get a sense of the campus and its resources. But the college’s website is also a great starting point. Look for one or two programs that align with your interest. Your mission is to find a reason why only this school can truly fulfill your goals and interests. These programs should be unique to that school. For example, you don’t just want to go to Duke because of their great economics major – every comparable school has the same major. Instead, you’re interested in the specific opportunity that Duke provides to combine the B.S. in Finance 10 with the B.A. in Econ because you want to study market implications of industrial labor decisions. Be careful not to tell the college things they already know. The essay is about you, not about the college. Don’t talk about the programs themselves; talk about how your values or goals specifically align with the programs. 3. The Creative essay: this essay evaluates your ability to think beyond the scope of the two other more common essay formats, testing whether you’re merely copying your essays from other schools’ prompts. Example: “What is square one, and can you actually go back to it?” (University of Chicago, class of 2021 admissions) This essay type is an opportunity to shine a light on your personality, views, and creativity. Not only does it make you think outside the box [pardon the pun] of traditional prompts, but it forces you to link your traditional insights to more abstract concepts or questions. These essays can be difficult because they often lead to confusing, obtuse, or unspecific writing. Make sure you make an argument about why your experience or insight connects to the topic. Remember to backup your argument with sufficiently clear detail. Think creatively, sure, but don’t let your essay drift off into the realm of fantasy. Stay informed and accurate. Exercise common sense. Avoid selfindulgence and eccentricity. No one cares about you pontificating on highminded subjects or bragging about your experience to exotic locales. Don’t forget: at top schools, admissions officers read thousands of essays. If yours is boring, impersonal, or badly written, they may not even read the whole thing. The University of Chicago is renowned for its provocative extended essay questions. Take a look at some of their mind-cookers from 2016-2017: • Alice falls down the rabbit hole. Milo drives through the tollbooth. Dorothy is swept up in the tornado. Neo takes the red pill. Don’t tell us about another world you’ve imagined, heard about, or created. Rather, tell us about its portal. Sure, some people think of the University of Chicago as a portal to their future, but please choose another portal to write about. • Vestigiality refers to genetically determined structures or attributes that have apparently lost most or all of their ancestral function, but have been retained during the process of evolution. In humans, for instance, the appendix is thought to be a vestigial structure. Describe something vestigial (real or imagined) and provide an explanation for its existence. —Inspired by Tiffany Kim, Class of 2020 11 03 Writing crash course 101 An important function of your application essay is proving that you can write. Not just that you can put words on a page, but that you capably weave a narrative arc through a personal experience that doesn’t repeat itself, utilizes syntactic diversity (not just “I did this,” then “I did that”), and exhibits precise word choice (did you say “it was loud in the theater” when you meant “the theater broke out into pandemonium”?). You’re going to be writing a lot in college, so it’s paramount that your essay shows you can efficiently and effectively communicate written ideas. Bring your A-game. This section is dedicated to giving you a booster course in the solid fundamentals for writing a high quality essay. 12 Finding your voice Writing, like music, makes people feel. Powerful prose can raise goose bumps on your skin. Yet, the choice of words, or their order, are not the cause of the emotions. The tone and voice are paramount. Tone is how a passage of writing makes you feel. Ask yourself when trying to identify the tone of the writing: is the language formal or informal? Is it complex or simplified? Am I the target audience? These questions can assist you in identifying tone. Voice is a quality that lets the reader know you wrote it. Ever tried to tell somebody else’s story? It’s wildly difficult to do because you will always add your own flavour to the story. Same with writing: voice is your unique personality shining through the words and igniting your reader’s imagination. You know when you’re reading Hemingway. They don’t waste time, are smart, and hate things that are overcomplicated. And you know when you’re reading a Buzzfeed article. Because each has a defined voice. Voice is utterly crucial to your personal essay because it conveys your personality–exactly what admissions officers are looking for. 4. Write down five publications or authors that you like to read and examine them. What are their similarities and differences? How does their writing intrigue you? 5. List your favourite artistic or cultural influences. They can be bands, painters, YouTubers, or anything in-between. How do they express themselves? Why do you like them? 6. Ask your friends and family to describe your voice. What impression do you give others? 7. Sit down and just write anything for 5 minutes. Literally anything. Then read it and ask: “When I write, do I sound like this or do I censor myself?” 8. Make yourself vulnerable. You should feel nervous, afraid, or worried when you submit your writing. If you feel calm about your writing, then nothing personal is at stake. Every writer has a voice. It is inseparable from you as a person. How do I find my voice? It’s simple. Here are eight easy exercises to help you identify your voice. 1. Describe yourself in three adjectives: e.g. ambitious, fun, and charismatic. 2. Read something you wrote a while ago and ask yourself: “Is this how I talk?” 3. Describe your ideal reader, someone who’d come back to read more from you. For example: my ideal reader has a sense of humour, understands pop culture, and loves technology. Once you’ve found your voice . . . Continue to develop it. Starting early on your college application is important, so that you have enough time to develop your voice in the essay. 13 Basic grammar and style Grammar Now that you have found your voice, let’s look at some of the fundamentals of grammar and style. You can find resources on grammar at the end of this chapter, which will help if you’re struggling with more intense areas of the subject, such as verb mood, subordinate clauses, and coordinate versus non-coordinate adjectives. Is the clause that I’m using essential to the sentence? We’ll also skip the basics, like what is a sentence and what is a clause, as you’ve probably got them covered. For example: The car that I want is out of my price range. (essential) For example: The car, which is only two years old, sold for $2,000. (non-essential) Like any good coach will tell you, solid fundamentals are the building blocks of talent. As an example, Picasso spent his early years as an artist mastering traditional styles and techniques, such as realism, portraits, and landscapes, before he pioneered Cubism. Grammar is the system and structure behind language – the source code. It’s a series of “rules” that guide the composition of words and help readers to understand your message in the writing. Style is the effective expression of thought through writing. It’s your choice of words, sentence structure, and paragraphing; style helps to convey meaning. Instead, let’s look at some of the things that trip most people up; knowing about them will dramatically improve your writing. That vs. which This one can be confusing. Where do you put that or which in a multi-clause sentence? Let’s look at their definitions: If yes, THAT If no, WHICH For example: The kitten that has white paws is the one I want (essential) For example: The kitten, which was my favourite, greedily ate her dinner (nonessential clause) Improper commas Some writers use far too many commas, and some barely use them at all. That introduces a restrictive clause. Correct comma placement subtly shows the reader that you know your stuff. Which introduces a non-restrictive clause. Let’s look at some examples: Confused? Well, that’s grammar for you. The easiest way to remember this information is replace the word restrictive with essential. • Introductory words, phrases and clauses need commas. 14 Style Incorrect: To become a good writer I must practice. Correct: To become a good writer, I must practice. • Non-essential information can be cordoned off with commas. Incorrect: Manu Ginobli who was born in Argentina is a shooting guard for the San Antonio Spurs. Correct: Manu Ginobli, who was born in Argentina, is a shooting guard for the San Antonio Spurs. • Essential information does not require commas. Incorrect: The boys, who vandalised the garden, are in police custody. Correct: The boys who vandalised the garden are in police custody. • Commas before direct quotation. Incorrect: Descartes said “I think, therefore I am.” Correct: Descartes said, “I think, therefore I am.” Hyphenation Always hyphenate adjectives that describe nouns. It helps clarify your meaning. Okay, so what is good style? Well . . . Good style expresses your message to the reader simply, clearly, and concisely. It keeps the reader attentive, engaged, and interested. And it shows your writing skills, knowledge, and ability. Bad style fails at one, two, or all three of these areas. For example: I put on my taped-together black horn-rimmed glasses. Keep this in mind as you write. You make stylistic choices for the reader, not your ego. If the reader doesn’t understand your message, your style has failed. Don’t forget to include a hyphen even if a word interrupts your descriptors. The basics of good style include: For example: The decision will impact our short- and long-term financial prospects. • Using straightforward and simple language. • Writing trim, lean, and punchy sentences balanced with the occasional long sentence for flavour. • Avoiding redundancies. For example: ready, willing, and able all mean the same thing. • Cutting out excessive qualification. For example: I have very many reasons for this. These lists can go on forever, so . . . • Comma splice: A comma can’t join two main clauses. Incorrect: Circumstances forced me into homelessness, nevertheless I kept up my studies. Correct: Circumstances forced me into homelessness; nevertheless, I kept up my studies. Here are some online resources with great search functions that can further assist with grammar and style. Daily Writing Tips GrammarBook • Using parallel forms. • Using the active over passive voice. E.g. “I loved Sally”; not “Sally was loved by me”. Also, style differs from voice. Style is how you choose and position your words on the page to convey the overall message, while voice is what makes your writing distinctly you. People can imitate your style, but they can’t imitate your voice. 15 How to self-edit Editing your work is crucial to cleanly convey your message. A first draft is never good and it will never get you into a top college. To give you an idea, most writers, editors, and organisations recommend at least two to four rounds of edits before publishing. Editing also requires an analytical type of brainpower that differs from the creative side of writing. Think of yourself as switching on a program in your brain called wordsweep. exe. Here are five quick tips to help you edit your own essay before you get someone else to review it: 1. Trim filler words. Common culprits include: There, it, here. They refer to nouns in your sentence, which means the sentence can be rewritten. Words like this rely on other filler words to help your sentence make sense – such as who, that and when. If college application isn’t “very scary”; it’s “terrifying”. you’re seeing these words a lot, then rewrite that sentence. • Example: There are writers who seem to think prose is easy. 4. • Correction: Some writers think prose is easy. Get your words to the gym and burn off that fat. • Example: It’s fun to go to college. • Correction: College is fun. 2. Make your verbs punch. Example: She is writing her application. • Correction: She writes her application. • Example: People are in love with yo-yos. • Correction: People love yo-yos. 3. Kill flimsy adjectives. Weak adjectives drain the power of your words. The writer isn’t “really bad”; the writer is “terrible”. Your Example: Alcohol is the cause of hangovers. • Correction: Alcohol causes hangovers. • Example: But the fact of the matter is, Pepsi tastes better. • Correction: But Pepsi tastes better. • Example: You’re going to have to edit your work. Inexperienced writers tend to soften their words. They let various verb forms (predominately to be) weaken the impact of their writing, instead of letting the verb do what it does best – show ACTION. • Burn flabby words. • • Correction: You must edit your work. • Example: Due to the fact that editing takes time... • Correction: Because editing takes time... 5. Get to the point. This is called nominalisation. It’s when the writer uses a weaker noun when a stronger verb or adjective replacement would make things much clearer and more punchy. • Example: Give your essay a proofread. • Correction: Proofread your essay. 16 Take your time Most applicants neglect their essay when preparing their college application. So essentially, allow 6 to 12 hours to work on each essay. To give yourself a head start, don’t make that mistake. Depending upon the colleges that you apply to, you may have to prepare up to 5 essays. It’s going to take some time to craft a tailored response for your targeted college. Follow these steps when crafting your essay: • Brainstorm ideas and develop core messages (3–6 hours) • Write your first draft (up to 4 hours) • Edit the second draft (1.5 hours of intense work) • Get your second draft reviewed (variable) • Write your final copy (1–2 hours) That will give you a full week’s worth of work to do, even if you only focus on writing essays! So remember, take your time. Plan and prepare. 26.2% College-level students’ writing classed as ‘deficient’. <50% College seniors say their writing improved during college. 17% College freshman need remedial writing class. Skip any step and you’ll lower the quality of your final output and, therefore, your chances of success. 17 04 What to avoid in your essay It is all too easy to flub your admissions essay. Admissions officers can smell a bad topic choice and weak writing from a mile away. The first three chapters of this eBook were dedicated to making sure that doesn’t happen to you. However, we should take a closer look at what would immediately disqualify your essay from contention. 18 Being too personal Showing bad judgement Being overconfident Admissions officers want to see your personality, but they don’t want you to cross personal boundaries. As much as taking an illicit substance may have changed your perspective on life, it’s definitely not material for the personal essay. You can believe in yourself, but no one likes a show-off. Your achievements are self-evident in the rest of your application. It’s far better to talk about a moment of doubt or a setback than to pat yourself on the back. You’ll find it hard to believe, but far too often, essays can wander into the realm of TMI (Too Much Information!). Admission officers have read essays from students where they have talked about losing their virginity, love interests or partners, and illegal activities. Use common sense. Ask yourself: does this topic, or do the details I’ve included, actually help a reader understand me better? Would I feel comfortable with someone I only just met reading this? If the answer is no, then you should choose a different approach. Don’t do it. However, it’s not just stories about drugs that show bad judgement. Making up a story about yourself or copying someone else’s work does too. Admissions officers, who have read tens of thousands of essays, can sense fraud when they encounter it. Also try to refrain from talking directly about your personality or traits in the first-person tense. For example, “I’m the type of person who likes...” or “I’m the hardest worker I know…” are definitely not good approaches to take when writing about yourself, as you quickly begin to seem like a narcissist. If you waffle on about your achievements, then you show no self-awareness of context and their actual scope. Even though Bill Gates founded Microsoft and rid the Americas of rubella, it would still be uncomfortable to hear him brag about it. So why would you? 19 Falling into the cliché trap This happens to thousands of applicants every year, whether intentional or not. Let’s give you a list of clichéd essays, so you know what avoid in your essay. Things to avoid • • • • Transcribing your résumé or talking about your main extracurricular activity: don’t repeat yourself. Admissions officers can read your résumé as well as you can. Community service or a trip to a third-world country that “moved you”: these essays tend to lack empathy, sound over-privileged, and be downright condescending. Unless you have a new or valuable insight – for example, if the lesson you learn actually indicates how little you were able to accomplish through your volunteer trip – then don’t write about this stuff. Whoa, I’m going meta or postmodern with it, maaan: the admissions officer thought it was clever the first thousand times that they read it. How I can fix the world: thinking that you, barely more than a teenager, can fix the world shows a lack of self-awareness, maturity, and perspective. There’s a fine line between being inspiring and being naive. • Starting with a famous quote: just don’t. If it’s an obscure quote that is superbly relevant to your essay, then an exception might be made. But Gandhi, Churchill, and Mark Twain are definite no-go’s. • Don’t compare yourself to an inanimate object: comparing yourself to a flower, or a tree, or your grandmother’s rocking chair doesn’t really give the reader insight into who you are as a person. It usually just comes across like a gimmick. • The dead dog essay: everyone has had some ‘tragedy’ in their lives. That’s not to minimize your personal tragedy — it’s just true. But writing about it in a college essay is all too common, and once again, unless it was a determinative moment in your life (which it might have been!), then it shouldn’t be written about. • The “I’m so well rounded” essay: colleges want to see your ‘personal narrative’, a compelling and focused account of what you most love or how you are best defined. Do not write an essay that leaps from one quality or activity to another without clear purpose. • The “look at how much I know” essay: the fact that you took an English class doesn’t mean you suddenly possesses a deep understanding of Aristotle. Your essay should be absolutely free of pure bragging. If you want to talk about how good you are at something, then you should tell the story of what it took for you to achieve that; never simply write, “I am great at _______” or “I am really passionate about _______.” • And finally, from a Harvard admissions officer: “Don’t make your essay sound like a lengthy recitation or a thesaurus. The essay is not a vocabulary test! Don’t feel the need to consult a thesaurus to impress us with your vocabulary. We want to get a glimpse of who you are, not who you think we want you to be. Relax; we just want to get to know you better.” 20 Failing to show personality Don’t be a jerk Applicants sometimes forget to inject feelings into their essays. They avoid sharing their emotions and end up writing a statement that reads like an end-of-month report from the corporate world. Don’t talk down to the reader: the only thing you really know is yourself and your own experience, so don’t try to tell them how the world works (or how anything works, really). Splash some colour on the page! Explore how the situation made you feel, and go into detail too. Avoid whining about your problems and how the world is out to get you. Don’t be pessimistic, cynical, or depressive – the future is bright, remember? Keep humour minimal – self-deprecating humour is probably the only type of comedy that translates on paper to a stranger, and unless you’re actually funny (meaning more than just your mom has told you that you are), it just isn’t a good idea. 21 05 Essay case studies The main event! We’ve compiled six personal essays from our students that were used in successful applications. Top US colleges accepted the students who wrote these essays. While we’ve redacted certain information to ensure privacy, these schools were in the top 100 US News rankings, including the Ivy Leagues. Our expert admissions officers review each essay and provide an analysis as to why it works. So without further delay . . . 22 Example 01 Word Count: 646 Children love what is simple, clear-cut, and absolute; they like primary colours and the pure, sugary rush of Coke. But adults prefer subtlety. Adults see the beauty of the shades between black and white. They recognize the multiple layers of scents and flavours in a single glass of wine. For me, adulthood means the ability to appreciate nuance. My journey into adulthood began as a quarrel with my mother, a fight about a treasured journal I had received for my 12th birthday. It was my most precious possession. The simple brown covers bound by black metal contained my every thought; I wrote in it every day. I was rapidly seeing a lot of things in the world that I hadn’t noticed before, especially with regards to authority. My teacher consistently chastises Jason for talking in class, but does not do so when Jane chatters. My church pastor tells me that God is allpowerful and loves everyone–so why do my friends still suffer from bullying? Ooh, my friend got a trampoline. Such was the jumbled nonsense that lay between the covers of my little brown journal. Yet these half-sensical sentences were the beginnings of my analysis of the world, documenting when I started to question what I had previously simply accepted. My time with my journal was priceless. These scribbles allowed me to process my questions and try to answer them. It was crucial that the contents of this journal were private. I needed to know that I could write anything without fear of being reprimanded, suffering social consequences, or annoying others. I was experimenting with the concept of keeping secrets for myself. Then I came home from school one day and had a huge fight with my mum. I cannot remember why we even started fighting, but I will always remember what she said. “And you, wasting so much of your time, writing in that stupid diary of yours? Do something useful for once!” My anger was immediately replaced by shock. Then, I realized how much I was hurt. Sure, I had argued with Mum before, but mostly over my laziness or a misunderstanding. This was the first time I honestly thought she was wrong. I asked myself, over and over again in my head, why she was doing this. Why did she want to take away my little world, rob me of the one place where I kept my own thoughts? What was wrong with having a little space, a little privacy? Mum had always been in my corner; she was the “good cop” who supported me through hard times. So why was she doing this to me? I struggle to reconcile these two opposing figures—the mother who always encouraged me to pursue my dreams and this mother who was trying to take away my greatest passion. I had previously observed and noted the paradox of a good person doing bad things, but this was the first time I was forced to resolve that cognitive dissonance. I now realize that the catalyst for our fight was a fundamental disagreement between Mum and me about personal boundaries. My mum has made huge sacrifices to allow me to follow my ambitions and become the person I want to be. I respected and still respect that. 23 She is a good person. However, the fact that she is my mother does not mean she is always right. After that fight, I learned to distinguish between being an “authority” and being correct. Ironically, I am glad that this happened because it was the first of a set of discoveries about morality. I came to understand that someone is never always right or wrong, that sometimes there is no such thing as an absolute, “right” answer. In other words, I began to appreciate the nuanced shades of grey between white and black. It was the beginning of my journey to maturity. Admissions Officer Analysis “ The student has shown here an awareness about their place in the world; even from the early examples out of the diary, we can see that the student makes keen observations about how we as people treat and judge each other in our society and what the student believes to be right and wrong. That being said, the student has also done a good job of ‘keeping it real’ with the trampoline excerpt and avoids coming across as trying too hard. On a more serious note, the applicant’s ability to analyze the root cause of a disagreement and to put themselves in the other’s shoes is a highly appealing trait to see in an applicant. It implies that the student is willing to listen to others’ opinions and consider different perspectives. At the same time, the student’s example of disagreeing with an authoritative figure also hints that this applicant will not be afraid to challenge professors in the classroom and provide intellectual discussion and discourse. ” 24 Example 02 Word Count: 649 I only realized the degree to which China’s governmental system needed to change when a woman came into my office crying. Volunteering at the Nantong Legal Consultancy Center, my job was noting people’s problems and referring them to the right lawyer. So far, I had met irate neighbors, calmed cheated workers, and reasoned with drug addicts and even a schizophrenic who shouldn’t have been out of the hospital. But calming this sobbing was still a little out of my comfort zone. Amidst her tears, I slowly pieced together her story. She had undergone a forced abortion fourteen years before, when she was nineteen and six months along. Yes, her pregnancy was against government policies at that time. Nineteen is below the legal age for marriage. No, there weren’t any records. And yes, there was lasting harm done. The procedure had left her unable to have children. I felt appalled. But the lawyer I sent her to spread his hands in a gesture of helplessness. Apparently, without records, he could prove nothing and was therefore unable to help. She left soon after, but I wasn’t about to let it go. That such a thing could happen and go so long without remedy was almost inconceivable to me, so I set out to try and right this wrong. I spoke with the lawyer again only to be discouraged gently. “You know, she comes every so often. She knows she won’t be compensated and doesn’t care much about that anyway. She comes here only for an acknowledgment of her pain.” Undeterred, I looked for ways to help beyond legal aid. That sweltering summer saw me searching high and low for a possible solution. To my dismay, the Compensation Fund of the Birth Control Bureau was a dead end. They couldn’t help because the protocols required proof for remuneration to be granted. And doctors, shaking their heads, informed me that medical reports alone wouldn’t be accurate enough to link her childlessness to an undocumented abortion fourteen years ago. In my research, I found that this woman, heartrending as her story was, was only a drop in the national bucket. Countless others shared her fate. Meanwhile, working at the Center opened my eyes to myriad other unacknowledged problems faced by the less fortunate: housing demolition, industrial conflicts, brutal law enforcement –the list went on. The little office I received these people in stood as a grim testament to their disillusionment with the impartiality of the law. Too often, these people were denied redress due to loopholes or outright injustice, proof that an adequate legal system does not yet exist in China. Petitioners listened to lawyers’ advice, nodded, and left, too weary to waste time and money on lawsuits with little hope of achieving anything. Too often, laws only applied if they benefited the state, not the countless victims entrapped in its shackles. Eventually, I saw that there could be no solution to the woman’s case and so many others, so long as the law wasn’t more credible in Chinese society. I realized that the Chinese people had to join together in calling for a stronger rule of law enforced by a system worthy of trust–only then could these forgotten cases be redressed. Sadly, this end is decidedly more than I can accomplish at this stage in my life; I can only hope 25 that the little I am currently able to do will raise awareness and help towards this goal. At this juncture, I realized that the best I can do is lend a sympathetic ear. At the end of summer, I saw the woman again. I made my way towards her, handed her a cup of tea, and sat down. “Hi, I was here the last time you came. I know your situation. Do you want to talk more about it?” I watched as her eyes softened and she began her story once more. Admissions Officer Analysis “ I personally appreciate the student’s quiet conviction and compassion that she has for the woman in the essay. Also, a large part of what makes this essay work here is that the student doesn’t go over-the-top - like so many of these types of essays often do - in pushing the student’s newfound interest in a social justice-related issue. The student’s voice is coherent, though their personality could afford to come through a little more. The student’s resilience, resourcefulness, and willingness to attack this issue from multiple angles also doesn’t go unnoticed here; through the narrative, the applicant demonstrates problem solving skills and the mental plasticity that gives the admissions officer an idea of how the student will contribute to intellectual discourse on issues on campus and in the surrounding community. ” 26 Example 03 Word Count: 650 I remember seeing them coming one by one, the army patrol vehicles thundering through the heart of the park, shattering the atmosphere of peace and harmony. Children stopped laughing and adults pointed and spoke in hushed tones, one lamenting “here they come again”. The smell of grease, intimidating sight of machine guns, and roar of heavyduty diesel engines sent a shiver down my spine. These were military national servicemen, patrolling the coastal region of Sembawang and guarding it against seaborne threats. At the back of my mind, I remember reminding myself that, in Singapore, military service is mandatory, and that I may one day be on those very patrol vehicles, something I dreaded. When I grew older, we moved to New Zealand, and thoughts of things back in Singapore faded. As I progressed in school, I discovered history, which I studied in in-depth terms. From Mesopotamia to the Cold War, I relished learning how people built on what came before, how individual nations added to the greater macroscopic trajectory of mankind. Being far from where most of what I studied transpired, I could approach historical concepts without bias and I felt that I gained the most insight on warfare. Whether it was the RAF bravely fighting for the sovereignty of the UK during the Battle of Britain or the colonists’ struggles for American Independence, I learned that warfare is sometimes essential if a nation is to exist. I became enamored of the “great man” theory of history, awed by the determination of figures such as Washington and Churchill. Seeing the necessity of the military for a nation’s peace and security, and naively resolved to become a great man in my own right, I returned home and did the thing that my younger self dreaded most: enlisted in the Singapore Armed Forces. Initially, the process of becoming a soldier was every bit as grueling and dehumanizing as I had once feared. I struggled to reassemble my M-16 with the requisite speed and was screamed at by the Sergeant Major, feeling flecks of his warm, angry spit as he excoriated me nose to nose. During the first road marches, I felt pushed to the physical breaking point and sometimes lagged, earning me more abuse that left me feeling further diminished. In these first months, I began to realize that I was not so special as I had once thought in high school, that the world had challenges that were larger than me, that I would have to grow more capable if were to be of any use to my country or myself. Fortunately, though, I made friends amongst those in my squad, brothers in arms in the original sense of the word. Everything I suffered, they suffered. When I flagged, they had a kind word, and the sight of their perseverance inspired me to persevere with them. From their example, I came to realize that our commitment was not a burden, but a sacred honor. Inspired by my fellow soldiers, I improved and was selected for officer training. It was in Officer Cadet School that I finally realized that history, despite the pages devoted to individuals, is a collective process. We emphasize the genius of one or two commanders each century while losing sight of the thousands who served with valor and ensured that campaigns would succeed. I realized that, if I were to truly lead, I would have to take all of my fellow soldiers into account. Where my passion for history 27 had completely transformed my view on the military, my newfound passion for the military now changed my view of history. Whereas once I felt fear, and later ambition, I now feel a sense of duty to serve my fellow citizens of our small city state, keep them safe amidst the world’s powers, to ensure that our nation’s future, its history as yet unwritten, is one of stability and peace. Admissions Officer Analysis “ The reader is given a very clear idea of how the student’s time in military has shaped his worldview. The last paragraph in particular emphasizes how the student demonstrates interdisciplinary thinking - something that many colleges are emphasizing in their curricula today. The student has also used a number of vivid descriptions - one thing that admissions officers often look for in an essay. The other essay idea that the student could have considered writing about is the student’s transition back ‘home’ to Singapore after having spent a significant time away in New Zealand and how that experience has shaped his identity and worldview, especially when the applicant is living in such close quarters with other Singaporeans who had spent their entire lives in Singapore. ” 28 Example 04 Word Count: 647 Laugh if you will, but my most important possession is a simple sketchbook that I received on my sixth birthday. To most the book might appear plain, but I felt immediately mesmerized by its myriad leaves and the cinnamon brown cover –it was beautiful in its simplicity. Receiving it felt almost like a rite of passage, an introduction to some future adulthood, but in retrospect, this book constituted a perfect reflection of my life at the time: blank yet filled with infinite possibility. Over the years my sketchbook became more of a place than a thing, a cave on whose walls past selves left paintings reflecting their days and preoccupations, crude smudges that advanced gradually to vibrant scenes teeming with movement and life. This cave served not only as a place for expression but also shelter: I ventured there often when I was young because I was lonely and felt I had no place else to go. Upon moving from China to New Zealand, my parents were always busy with designing and renovating houses in order to build a life here, literally. At school, I struggled to learn English and struggled even harder to make friends. The language barrier seemed too much, and I became a reclusive boy who wasn’t keen on talking to those around me. However, in this time of darkness, drawing was my salvation. Even if my peers couldn’t understand or communicate with me, they could decrypt my simple doodles. In elementary school, these little moments of acceptance gave me a newfound happiness, a happiness that showed that despite all the awkwardness and inexpression, I was valued in this new and foreign environment. Time went by and I repeatedly changed schools. After the initial victories from sketching cartoon characters wore off, I slowly went back to the shy boy that I had always been. While my English had improved, my self-esteem did not improve with it. I was different, and wherever I went people didn’t really seem to accept that. In a total of three primary schools, I can only really recall four real friends. At times, the pent-up frustration and sadness really got to me, and it was then that I returned to my cave, on whose walls on I could express everything without limitations. Secluded there, I was free from the constraints of the outside world. Then came high school, and the day I entered secondary education also became a watershed. I made friends, friends that I could talk to and rely on. My friends and I exchanged ideas and thoughts at human rights conferences and online film review platforms; we learned how to be leaders while organizing different competitions and camps in and outside of school; we even decided to go on service trips to the other side of the world. Soon, I came to see my cave as more akin to the one in Plato’s famous analogy than Lascaux, and I never looked back once I ventured forth into life with all its complexity. As extracurricular activities and schoolwork piled up, free moments became increasingly scarce. More and more I neglected my sketchbook, which had so faithfully recorded my journey. It lay at the bottom of my study drawer, forgotten for years, the cave’s entrance sealed with the advance of time. When I rediscovered my sketchbook late in high school, all the memories came flooding back like images in an archaeologist’s flashlight. The miniature 29 cartoons drawn as a little boy led to the detailed sketches from later, documenting a personal evolution towards the present day that I was scarcely aware of at the time. In that moment, I saw that the cave had not held me back from life, but instead afforded a place where I was free to grow. I was no longer that quiet, lonesome boy who struggled to make friends. Thanks to my sketchbook, I had changed. Admissions Officer Analysis “ The sketchbook is a nice vehicle that gives us an insight to the student’s background, but unfortunately doesn’t fully give us a window into who the student is today and who they could have been (apart from the student being your average stressed out high school student balancing schoolwork and extracurriculars). The student starts off well here in using the sketchbook to connect to others when they were younger, but the essay’s overall message gets lost towards the end. I would have much preferred a vivid telling of this evolution by the student in the last paragraph instead of simply telling me that they have changed. ” Once again, you want to show as much as possible, not tell. What this essay does well is convey a personal story followed by its impact on the student today. 30 Example 05 Word Count: 624 Sitting in my makeshift darkroom, I shut off the water spilling into the developing tank. My prize perches languorously in a bath of chemicals. I uncoiled the film, and see memories strangely unfamiliar in their plastic permanence. Pictures accentuate life. An image of soldiers dug in a dystopian wasteland was one of the earliest to lodge itself in my memory. After asking where the place in the photo was, I was told “overseas”. Soon after, I felt uneasy upon learning that Dad also intended to move our family from Hubei, China to overseas. For days after, I was convinced that New Zealand embodied the hellscape I’d seen in the picture. My fears were quelled by the sight of suburbs, pūkekos, and greenstone when Mum and I and landed there. We never really unpacked, In the twelve years since, I’ve changed houses ten times. I took lots of pictures with my digital camera, but as I was picked up and dropped off at new thresholds over the years, I lost touch with the places of my childhood. With each new place, best friends faded into memory, lost amidst hundreds of pictures on my desktop and cell phone. If one picture spoke a thousand words, then I carried millions of words all spoken at once; their competing clamor ensured that none had a chance of achieving meaning. As reality seemed to slip away with no sense of continuity save that of the calendar, I was rescued when my mum gave me her old Nikon and a single roll of film. I rationed that roll over a whole summer, became selective guardian of thirty-six tiny moments, armed with the means to etch my viewpoints into something tangible. As I selected, condensed, and stitched together intermittent points in time, I practiced deliberate reflection in each moment. With so few possible pictures, I was forced to live first and photograph second. I grounded myself in reserving space for analogue in a digital world. Like the light hitting the gelatine coating with no filter in its path, I took to directly imprinting people and emotions onto my consciousness. This mindful sensitivity made me feel, finally in control. At the end of this summer, I scanned and examined the negatives and saw concrete proof of life and memory. Here, the apples swell on our tree the first time. My father holds a pumpkin up amongst the branches, chortling like he found it growing there. Here are the globs of stardust I enjoy observing, the tennis courts on which I drill serves until it feels like drumming a rhythm. And here, Upper Tama Lake greets me when I finally arrive, drenched and windburned. On our sixth and final day, a question had divided our hiking group: agree to the uphill detour, or decline in favour of a shower? The blue glass water urges me to continue. The truest snippets are the frames that aren’t meant to be there, or at least not meant to look how they do. The strikingly framed picture of a twisting tree is marred by my startled face darting out of the top corner. I find that I had blackened my frames from a twilight walk in Queenstown, because I hadn’t adjusted my exposure for the settling dusk. Here, I realize that actual memory will have to suffice. The beauty of taking pictures with this camera, for me, comes from the realization that the frame doesn’t need me inside to show me who I am. With every frame, I am 31 reminded of the things that constitute myself: who and what I love. With these images I have proof, however slight, of the moments I value, and a timeline, as my life unfolds in a roll of film. Admissions Officer Analysis “ The student here has used the photo as a vehicle to convey a number of details to the admissions officers that they would not have known otherwise (i.e. moving 10 times in 12 years). The essay also demonstrates to the reader the student’s critical thinking abilities when analyzing the power of the photo while never neglecting its importance to the applicant, making the essay on a fairly common topic highly personal and unique to the student. The usage of vivid verbs and adjectives also help to transport the reader to the student’s mind and give the reader an insight to the student’s worldview. One thing I’d like to see more is to see the student’s personal growth and maturation through photo. ” 32 Example 06 Word Count: 624 I entered my summer internship in the corporate industry expecting to learn from successful people in a business setting. But here I was, sitting at a rough-hewn table in a cabin deep in the Tūwharetoa region with four other men, waiting for the clock to strike ten. While in the office these men were prim creatures, impeccably suited and lowkey, now, in the night, in the woods, they had undergone a sort of lycanthropic transformation: they were coarser, animated by competitive machismo and the prospect of the hunt. I watched the minute hand drag itself across the face of an ancient cuckoo clock with unease. Whereas beforehand I was excited for the trip, viewing it as an invaluable opportunity to experience the business world, now, as the journey’s ostensible purpose drew near, I was definitely having second thoughts. The clock groaned out the hour and the plumpest, most senior man of the bunch shot to his feet yelling: “Dinner ay boys!” I looked at the leftovers in front of us: we didn’t need any more food. Shouldering our rifles in unison we piled into a 4X4 SUV whose spotlights flooded the night. I sat amongst two middleaged men who questioned me about my plans for the future in tones of beery camaraderie. In one movement, one of the men swiftly raised his ancient Mauser and pulled the trigger. Conversation ceased. Alarmed, I peered out of the front window. A deer lay dying: its head twitching and sides rising up and down in an ever-slowing rhythm. “He’s a top-notch violinist– I went to his charity recital. Will you further that then, eh?” one commented. “Do it!” One of the men dropped a gun in my hands and beckoned towards a second one, standing motionless in the blinding beam of the floodlights. “But he is an athlete. With the brains!” the man on my left added in a husky voice. Soon, conversation quickly shifted to the matters at hand. “This is really important,” one said, “Hunting is embedded in the way we live.” If hunting was embedded in the way these men lived, it was embedded in it much the same way that their sailboats or Maseratis were, a non-essential that they took for granted. These men were some of the most influential business figures in the country. The truck came to an abrupt halt, and there was a silent whir as the sunroof opened to reveal the glittery night sky. I looked down the barrel for a moment towards the deer–its eyes glistening like some outsized mouse. With reluctance, I ejected the live shell into the dark night and dropped the gun, creating a loud “thunk” that I hoped would scare it away. It didn’t. The man next to me shot the deer without hesitation. My whole body was numb as I hauled the still-warm carcasses to the carving shed. As the thick blood soaked through my shirt, I felt an overwhelming sense of regret wash over me. Why did they need to kill these deer? More importantly, why didn’t I stop them? These men could have or do anything, yet here we were killing for sport masquerading as necessity. 33 Monday when I strode into the office, greeted by cool air-conditioning and the usual “good mornings,” I saw two of the men from that weekend and realized something had changed. Last Friday I had wanted to be just like them; today, I didn’t. Although they were financially successful, that wasn’t enough. I realized that my idea of success had nothing to do with money, and everything to do with how one approaches the world around him. I resolved that in the future, no matter what position I was in, I would act according to my conscience, take no more than I needed, and show mercy always. That would be success. Admissions Officer Analysis “ The main issue is this piece comes across as overly narrative. The hunting story takes up a large chunk of the essay only to make the student’s point at the end of what their idea of success looks like. I’d personally be more interested to see the student’s idea of success in action post-‘hunting story’; you want to show, not tell, your point as much as possible. Also, while I generally do not advocate using ‘SAT-type’ words in your personal essay for a myriad of reasons, this student has managed to use a number of fairly advanced words that - most importantly - remains consistent with the student’s voice in this essay. This is not necessarily a bad essay, but it is not one that would ‘seal the deal’ other aspects of the application likely played a role here in the decisions to admit the student. ” 34 06 Final thoughts There you have it, folks - an introductory crash course in how to write a personal essay to a US college. We learnt admissions officers measure successful essays with three key indicators, with splashes of other soft indicators. If you write to these indicators and to the types of essays colleges expect, it’ll improve your chances of success. We had a brief look at what makes writing good and what makes it a disaster. And we closed the show with six successful essays. It doesn’t seem that hard now does it? If you’d like to learn more, or how to tailor your essay to a specific college, please call for a free consultation where we’ll assess your candidacy to particular schools and how to improve your chances of getting accepted. Also, stay tuned for part two of this guide - so much to cover. We gave a basic overview of grammar, style, voice and tone. We showed you what you utterly need to avoid. 35 Made with by Crimson 36