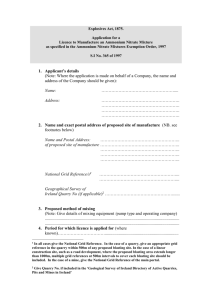

SAPIENZA UNIVERSITÀ DI ROMA DIPARTIMENTO DI SCIENZE DELL’ANTICHITÀ SCIENZE DELL’ANTICHITÀ 26.3 – 2020 EDIZIONI QUASAR SAPIENZA UNIVERSITÀ DI ROMA DIPARTIMENTO DI SCIENZE DELL’ANTICHITÀ SCIENZE DELL’ANTICHITÀ 26 – 2020 Fascicolo 3 EDIZIONI QUASAR La Rivista è organo del Dipartimento di Scienze dell’Antichità della Sapienza Università di Roma. Nella sua veste attuale rispecchia l’articolazione, proposta da Enzo Lippolis, in tre fascicoli, il primo dei quali raccoglie studi e ricerche del Dipartimento, gli altri due sono dedicati a tematiche specifiche, con la prospettiva di promuovere una conoscenza complessiva dei vari aspetti delle società antiche. Le espressioni culturali, sociali, politiche e artistiche, come le strutture economiche, tecnologiche e ambientali, sono considerate parti complementari e interagenti dei diversi sistemi insediativi di cui sono esaminate funzioni e dinamiche di trasformazione. Le differenti metodologie applicate e la pluralità degli ambiti presi in esame (storici, archeologici, filologici, epigrafici, ecologico-naturalistici) non possono che contribuire a sviluppare la qualità scientifica, il confronto e il dialogo, nella direzione di una sempre più proficua interazione reciproca. In questo senso si spiega anche l’ampio contesto considerato, sia dal punto di vista cronologico, dalla preistoria al medioevo, sia da quello geografico, con una particolare attenzione rivolta alle culture del Mediterraneo, del Medio e del Vicino Oriente. I prossimi fascicoli del volume 27 (2021) accoglieranno le seguenti tematiche: 1. Ricerche del Dipartimento. 2. Roma e la formazione di un’Italia “romana”. 3. Pratiche e teorie della comunicazione nella cultura classica. DIPARTIMENTO DI SCIENZE DELL’ANTICHITÀ Direttore Giorgio Piras Comitato di Direzione Anna Maria Belardinelli, Carlo Giovanni Cereti, Cecilia Conati Barbaro, Maria Teresa D’Alessio, Giuseppe Lentini, Laura Maria Michetti, Francesca Romana Stasolla, Alessandra Ten, Pietro Vannicelli Comitato scientifico Graeme Barker (Cambridge), Martin Bentz (Bonn), Corinne Bonnet (Toulouse), Alain Bresson (Chicago), M. Luisa Catoni (Lucca), Alessandro Garcea (Paris‑Sorbonne), Andrea Giardina (Pisa), Michael Heinzelmann (Köln), Mario Liverani (Roma), Paolo Matthiae (Roma), Athanasios Rizakis (Atene), Avinoam Shalem (Columbia University), Tesse Stek (Leiden), Guido Vannini (Firenze) Redazione Laura Maria Michetti con la collaborazione di Martina Zinni SAPIENZA UNIVERSITÀ DI ROMA SAPIENZA UNIVERSITÀ DI ROMA 14-15 DICEMBRE 2017 LA MACEDONIA ANTICA E LA NASCITA DELL’ELLENISMO ALLE ORIGINI DELL’EUROPA a cura di Francesco Maria Ferrara, Pietro Vannicelli Per Enzo Lippolis, con il quale questo convegno è stato pensato e organizzato INDICE F.M. Ferrara, Premessa . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1 J.K. Davies, The Impact of Macedonia . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3 I Sezione. Atene e la Macedonia P. Vannicelli, Tucidide e il modello erodoteo: la spedizione di Sitalce in Macedonia del 429/8 a.C. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 25 M. Mari, Anfipoli diventa macedone: Filippo II e le lezioni della storia . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 39 M. Faraguna, Una città in attesa: Atene, Alessandro e la Macedonia tra realtà presente e memoria del passato . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 51 F. Landucci, Atene tra Cassandro, Demetrio e Lisimaco . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 69 II Sezione. Lo sviluppo della Macedonia: città e territorio A. Kyriakou, The Sanctuary of Eukleia at Vergina / Aegae: Aspects of the Development of a Cult Place in the Heart of the Macedonian Kingdom . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 85 A. Koukouvou – I. Psarra †, Ancient Mieza: a Macedonian City from the Perspective of its Public Space . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 99 A. Koukouvou, Building Cities in Macedonia. The Stone Quarries and the Urban Development of the Kingdom . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 119 S. Drougou – C. Kallini, The Metroon at Aegae (Modern Vergina). Archaeological Evidence of the Cult of the Mother of the Gods . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 133 B. Tripodi, La II tomba reale di Vergina quarant’anni dopo. Qualche riflessione ‘extravagante’ . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 143 VIII Sc. Ant. III Sezione. La Macedonia nella Grecia settentrionale: la Tessaglia e l’Epiro G. La Torre, Skotoussa e il regno di Macedonia tra IV e II sec. a.C. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 157 L. Campagna, Il linguaggio architettonico della Tessaglia in età tardo-classica ed ellenistica: considerazioni preliminari a partire dal caso di Skotoussa . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 173 G.M. Gerogiannis, Larisa di Tessaglia e la Macedonia. Monumentalità e trasformazioni della città . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 191 E. Santagati, Pirro: un velleitario epigono di Alessandro in Occidente . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 207 L.M. Caliò – R. Brancato, Sviluppo urbanistico, fortificazioni e viabilità nell’Epiro ellenistico: il caso della Valle del Fiume Vjosa (Albania meridionale) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 217 IV Sezione Spazi, comportamenti, contatti, influenze F.M. Ferrara, Società e architettura privata nella Macedonia ellenistica . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 247 S. Guidone, Dalla Macedonia all’Italia meridionale: forme e modelli dell’architettura privata . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 265 R. Graells i Fabregat, Hellenistic Cuirasses: Shapes, Decorations and Influences Between Macedonia and Southern Italy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 281 J. Thornton, Gli ultimi Antigonidi nella tradizione storiografica: cenni sull’ostilità di Polibio a Filippo V . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 299 A. Sassù, Ex Macedonia et De Rege Perse: il bottino di Lucio Emilio Paolo in Grecia . . . . . 311 Angeliki Koukouvou BUILDING CITIES IN MACEDONIA. THE STONE QUARRIES AND THE URBAN DEVELOPMENT OF THE KINGDOM The tremendous growth in urban life in Macedonia in the 4th century BC, as new urban centres were founded1, old ones re-developed and ambitious building projects carried out all over the kingdom2, is a phenomenon whose technical aspect has often been ignored in related studies. How were all these cities built? This is the question we will try to answer, in an attempt to partially cover the large gap in research in this field. The important archaeological remains revealed from 1999 to 2002 in the rescue excavation carried out during the construction of the new Egnatia highway in Emathia prefecture placed a new, hitherto unknown, site on the archaeological map. These remains, brought to light on a natu‑ ral plateau near the modern settlement of Asomata between Vergina (ancient Aigeai) and Beroia on the south-eastern slopes of Mount Vermion, span a broad chronological period: from the Late Neolithic to the post-Byzantine era (Fig. 1). For the most part they consisted of grave clusters, with some buildings and remains of workshops, most probably belonging to farmhouses. In ad‑ dition, two ancient poros quarries (Quarries 1 and 2) came to light on the slope of the plateau. Another ancient quarry (Quarry 3) came to light 1.7 km away, near the modern entrance of the city of Beroia3 (Figs. 2-4). The Asomata quarries (as we shall name them for the sake of brevity) are the first building-stone quarries to be excavated in Macedonia and among the very few in the whole of Greece4. Quarry no. 2 offered the most extensive evidence regarding ancient quarrying activity. It was the largest and the best preserved and, most importantly, it had been filled in soon after the cessation of quarrying operations in ancient times, thus providing a unique opportunity to study quarrying techniques at firsthand, unaffected by weathering. The site preserved piles of quarry rubble, stone chips, dumped cut blocks in situ, unfinished blocks still attached to the bedrock, their extraction never completed, as well as many tool marks in excellent condition5 on the quarry 1 Hatzopoulos 1996, I, pp. 105-123. Hatzopoulos 1997, pp. 11-16. For an overview of the settlements in the Ma‑ cedonia region and their status (e.g. poleis, komai, etc), see Hansen - Nielsen 2004, pp. 794-809 (M.B. Hatzopoulos - P. Paschidis). 2 Koukouvou - Psarra in this volume. 3 On the excavation at the site of Asomata, Emathia (Macedonia, Greece) see Koukouvou 2000; 2001; 2004, pp. 58-70; 2012, pp. 123-134. On the archaic cemetery of the site see Kefalidou 2009. 4 On the rarity of excavations of quarries, see BESSAC 1996, pp. 83-84. See also the remarks of Lazzarini (during the concluding discussion of the colloquium on the building stone (Domikos Lithos 2002, pp. 352-353) about the need to excavate ancient quarries. The lack of systematic research is especially evident in the Greek region, most notably for quarries of building stone, see Koukouvou 2012, pp. 45-51. On the Asomata quarries see Koukouvou 2012. See also the proceedings of ASMOSIA I-XII. The mission of the Association for the Study of Marble and Other Stones in Antiquity (ASMOSIA) is to promote the study of marble and other stones of art historical or archaeological interest, mainly by organizing conferences and publishing their proceedings. From 1988 till 2018 twelve meetings have been organized, promoting interdisciplinary cooperation and research, dealing with themes as provenance and use of marbles and other stones, quarrying techniques and transport, identification, restoration, and several more. 5 For Quarry 2 in Asomata see Koukouvou 2012, pp. 145-163. 120 A. Koukouvou Sc. Ant. Fig. 1 – Aerial photograph. The excavation near the Asomata village and the city of Beroia in the background (© Greek Ministry of Culture & Sports). Fig. 2 – Asomata, quarry 1 (© Greek Ministry of Culture & Sports). 26.3, 2020 Building Cities in Macedonia Fig. 3 – Asomata, quarry 2 (© Greek Ministry of Culture & Sports). 121 Fig. 4 – Asomata, quarry 3 (© Greek Ministry of Culture & Sports). faces and beds (Figs. 5-6). It is confirmed that quarrying hit the bottom of healthy parent rock in many places, reaching cavities or areas of unsuitable material. In this case, a large cavernous cham‑ ber caused the partial collapse of the quarry floor, forcing the workers to backfill it with debris in order to construct a new working platform and to continue quarrying in other locations (Fig. 7). The quarry had two entrances and quarrying in both branches developed on a rectangular plan, with reference to a level plane that was established to serve as the quarry’s floor. As dig‑ ging proceeded, the gradual stepped extraction of the sloping ground enlarged the floor, and the back and side walls of the pit were turned into increasingly high scarps. Since the floor was main‑ tained at the same level while operations proceeded, the side of the pit served as its entrance6. Our study of the quarries consisted of the systematic recording and analysis of all elements surviving in the three quarries, that is, the existing traces on their surfaces, the dumped and unfin‑ ished blocks, and the quarry rubble (latype) found within or around them. We used this informa‑ tion along with the available data from certain quarries in areas such as Corinthia, Kleonae, Aegi‑ na, Piraeus, Rhodes and Isvoria near Naoussa. This comparative study helped us to document the quarrying methods applied, to identify the tools used, to estimate the shape and size of the blocks extracted, to comprehend the difficulties the quarrymen faced, and to evaluate their level of skill. Our conclusions concern all the quarries of the stone which the Classical sources called poros stone or porolith, the common building material used in ancient architecture7. We use the same term in archaeological literature when referring to medium-hard to soft sedimentary lime‑ stones with margaic inclusions, sandstones, calcareous or volcanic tuffs, travertines, etc.8 The last, 6 For this type of quarry, common on slopes, see Röder 1971, pp. 260-264 (type I – Lehnenbruch) and Bessac 1986, pp. 167-170. 7 The term was used in Antiquity not just for one type of stone with specific geological characteristics but also for a whole category of relatively soft stones that could easily be quarried in rectangular blocks of any given dimension and used as building material. For a corpus of the building-stone quarries of Greece, see Koukouvou 2012, pp. 61-109. See also ibid. pp. 110-119 for a summary presentation of the most important quarries of the corpus. 8 Πῶρος, πώρινος λίθος, πόρος or ποῦρος in ancient Greek inscriptions. For these terms see, Orlandos - Travlos 1986 s.v. πῶρος, πώρινος, also Ginouves - Martin 1985, p. 40 s.v. “poros”, no. 211 and Hellmann 1992, pp. 364-366. The most extensive study of the meaning of the term belongs to Wycherley 1974. For the use of poros limestone in Anti‑ 122 A. Koukouvou Fig. 5 – Quarry 2 with piles of quarry rubble, unfinished and dumped blocks (© Greek Ministry of Culture & Sports). Sc. Ant. Fig. 6 – Among the quarry rub‑ ble and the unfinished blocks in Quarry 2, a curved architectural member (for a column?) is visible (© Greek Ministry of Culture & Sports). Fig. 7 – The working platform, made of debris and a layer of small stones, that covered a large cav‑ ity of the quarry floor (© Greek Ministry of Culture & Sports). travertine, is the carbonate sedimentary rock that exists in the area and was extracted from the Asomata quarries. According to our observations, the quarrying techniques used were common to all three quarries. Extraction was effected by cutting vertical channels, 6-11 cm wide, around the perimeter of the block to be extracted. A percussion tool with a long handle and a sharp edge, 2 cm wide, was developed specifically for soft stone quarrying. Its traces are preserved on the narrow cutting trenches and the quarry walls either in the form of shallow parallel grooves or as a fishbone pat‑ tern, due to the alteration in working direction of the quarryman (Fig. 8). The separation of the stone blocks from the parent rock was achieved by cutting a continuous shallow horizontal chan‑ nel at the base of the block. Metal wedges were then placed in this channel at regular intervals, as is revealed by V-shaped traces on certain parts of Quarry 2. The use of wooden wedges is not docu‑ quity see Orlandos 1958, pp. 67-70 and Koukouvou 2012, pp. 53-60, with the relevant bibl. For the importance of the geological factor in ancient architecture, see also Korres 1988. 26.3, 2020 Building Cities in Macedonia 123 mented through our observations at the excavated quarries. The extrac‑ tion technique employed at Asomata was widely used for the extraction of soft building stone such as poros. This method of vertical perimetrical channels that reached the final depth desired has resulted in the quarry taking on a grid-like appearance with straight lines, vertical walls, flat floors, right angles and regular levels9. Quarry 2’s total area is approxi‑ mately 450 m² and the total volume of quarried rock is calculated to have been 1125 m³. Its varying gradual lev‑ Fig. 8 – Traces of the extraction preserved on the floors and the walls els, as well as the traces on the wall of the quarry (© Greek Ministry of Culture & Sports). surfaces and floors, testify that blocks of various shapes were quarried. Most were rectangular, 1.10 to 1.60 m in length, 45 to 75 cm in width, and 45 to 70 cm in height. It appears that square blocks were also cut, 1 m by 1 m by 50-55 cm; these were probably needed for curved architectural members, as indicated by traces of carv‑ ing as well as a segment of a column that had not been released from the main block, found in the quarry (Fig. 6). The dating of Quarry 2 was based on the finds from the rubble layers and the fill of the quarry pits, which served as a terminus ante quem for their period of use: the quarry was opened and operated during the 4th century BC, most probably in its second half10. It must have been in use only for a limited period of time, and once abandoned did not remain open for long; nor was it re-used later on. This abandonment, necessitated by depletion of healthy rock and the appearance of natural flaws, suggests that work may have continued at another quarry nearby11. Quarries 1 and 3 were similar to Quarry 2 in physical appearance, general form and arrange‑ ment, but smaller in size. Their dating is more uncertain but we can place the period of exploitation of Quarry 1 in the late Classical-Early Hellenistic period and of Quarry 3 in Hellenistic times12. Archaeological research in the region identified more sites with traces of ancient quarrying on the western slope of the modern-day Egnatia Highway, in the form of exposed, stepped or sheer worked faces and floors, across a zone extending over a distance of 2 km between the River Haliakmon in the Asomata area and Beroia. These finds are similar to the layout of quarries in other regions, such as Corinthia, Kleonai, Delphi, etc., where extraction sites consisting of groups of smaller units have been found13. In the Asomata-Beroia region, therefore, as in the other areas mentioned above, the quarries covered an extensive area with multiple spots of 9 For the technique see Koukouvou 2012, pp. 181-195 (with bibl.). We must bear in mind that this method, which offers exceptional accuracy, differs greatly from that widely used in quarries of marble and easily split rocks. In the latter case, blocks are detached by means of the cutting of shallow channels and using crowbars and wedges, metal or wooden, in the seams. This results in the formation of uneven surfaces, irregular levels and angular corners. 10 For the difficulties in establishing a quarry’s chronology, see Koukouvou 2012, pp. 48-50. For the chronology of Quarry 2, see ibid. pp. 158-163. 11 Bessac 1996, pp. 103-105. 12 See Koukouvou 2012, pp. 163-174. 13 Koukouvou 2012, pp. 175-176. For the extensive quarrying zones at other sites, see Papageorgakis - Kolaiti 1992, p. 37; Marchand 2002, pp. 251-252, 271-273, 276-277; Hayward 2003, pp. 18-27. 124 A. Koukouvou Sc. Ant. intensive activity. Such stone extraction speaks of human activity in the form of quarrying and transportation, with a significant impact upon the environment as well as the region’s everyday life and economy. With regard to Asomata, the archaeological data and our calculations indicate that a large quantity of building material was extracted from this quarrying zone, in the form of big rectangular blocks destined for large public buildings and other monumental structures, such as fortification walls and secular or funerary monuments. The location of the excavated quarries, between two important ancient Macedonian cities, Aigeai and Beroia, raised a logical question regarding the destination of the large quantities of extracted material. It was certainly intended for the construction of large public buildings, obviously not to be found in a small and insignificant settlement like Asomata. But where was it going to be used? The 10 km of distance between Vergina and Beroia leaves no space to postulate another Hellenistic city with its essential surrounding chora, as a possible recipient of all this building material14. Furthermore, the geological study that was done for the area showed that Beroia could easily extract sufficient building stone from its parent rock. On the geological map it is evident that the area of the travertine deposits, on whose southern boundary we find Asomata, is located exclusively north of the Haliakmon15. In the region of Vergina there is no travertine, nor any other rock suitable for construction purposes. Yet the travertine, which we archaeologists call poros, was used for all the monuments of a secular and funerary character in the city of Aigeai: the magnificent palace, the fortifications and the Acropolis, the theatre, the other civic buildings, as well as for all the monumental Macedonian tombs16. These findings led to the formulation of the following working hypothesis: the large quantities of building stone extracted from the quarries of the Asomata area were destined for the neighbouring city of Aigeai and the construction of important public buildings in the first capital of the Macedonian kingdom. To test this hypothesis, we examined samples from the Asomata quarries and from monuments at Vergina (Aigeai) and other sites in Emathia. An updated multi-method analytical approach was applied in the characterization of stone from quarries and monuments, with the aim of obtaining archaeometric information on provenance. More specifically, we determined the samples’ mineralogical, chemical and isotopic composition using petrographic examination, optical and scanning electron microscopy, X-ray diffraction spectroscopy, geochemical analysis through inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP/ MS), as well as determination of stable isotopes of carbon (13C) and oxygen (18O). The results were very rewarding. The samples from the Asomata quarries and those from the ancient monuments of Aigeai show clear similarities regarding their mineralogical composition, their content in major elements, trace and rare earth elements, but also in their isotopic composition. The results of the isotopic study show that almost all samples from the ancient monuments of Aigeai (nine out of twelve) fall within the range of the excavated quarries at Asomata (Quarries 1 14 For the ancient cities in the region and their territories see Papazaoglou 1988, pp. 124-127, 131-135, 141-149. See also Gounaropoulou - Chatzopoulos 1998, p. 47. For the ancient ‘χωρία’ of the same region, see ibid. pp. 48, 141 and Koukouvou 1999, pp. 574-575 with notes 15-18. This settlement probably belonged to the land of Beroia. See also Koukouvou 2012, pp. 132-134. 15 See Koukouvou 2012, pp. 134-136. 16 See Romaios 1953-54, p. 144; Andronikos et al. 1961, p. 28; Andronikos 1989, pp. 64, 66, 68; Kottaridou 1992, pp. 68-69; Drougou 1992, p. 48; Saatsoglou-Paliadeli 1992, pp. 55-56; Kottaridou, 1993, p. 83; SaatsoglouPaliadeli 1996, pp. 58-60; Faklaris 1996, p. 70. See Drougou 1999, p. 536, where the material of the monuments is mentioned as poros stone. For the building stones used in the construction of the Palace of Aigeai see Kouzeli 2007, pp. 152-153. 26.3, 2020 Building Cities in Macedonia 125 and 2). The results of the archaeometric study therefore strongly support the probability that the building stone used in the monuments of ancient Aigeai came from the Asomata quarries17. The interdisciplinary research into the possible destination of the building material from the Asomata quarries, namely the reconstruction of the now lost history connecting quarry and monument, was dictated primarily by the unanimous belief of scholars that in Antiquity, at least until the late Hellenistic period, there was a close quarry-monument relationship18. A connection so close that it causes us to recast the well-known causality dilemma: “which came first: the chicken or the egg?”. Did the monument make the quarry, or the quarry the monument? Large-scale public projects required considerable quantities of building stone and, at least during the Classical and Hellenistic periods, there were no quarries in the form of established enterprises where one could order blocks, columns, etc., from a ready-made stock. The opening of a quarry and the extraction of rock were the first stages in any building work and began only after a contractor took over the project and a “contract” of construction (a syngraphe in Ancient Greek) was officially signed. These contracts, which state in detail the builders’ obligations, and the construction accounts are important, firmly dated, official financial documents that provide us with authentic details about the extraction, initial rough treatment and shipment of building stone19. They also document the costs and the elaborate organisation required for the acquisition of stone masonry in Classical and Hellenistic times. Although our sources say little and are often vague, it is evident that the opening of a building-stone quarry followed a specific order, which determined the precise final dimensions of the blocks to be cut, the initial rough treatment on site and their shipment to the final destination. As the document show, these stages were viewed as an integrated whole, which was frequently undertaken by the architects in charge. For example the decree of the Epistatai (that is, the commission of public works) of the polis of Eleusis, dated in the middle of the 4th century BC, specifies the number of stones (λίθους) to be quarried (τεμε̑ν), transported (ἀγαγεῖν), unloaded (καθελέσθαι) and finished (ἐργάσ[ασ]θαι) for the making of different architectural elements20. Here we have textual evidence about the exact dimensions and foot units that correspond to the blocks. Inscriptions like this are very important in understanding the ancient quarrying methods because they allow us to see the design and planning methods as well as the construction history of the building. As also indicated in the inscription, transportation was a very important, laborious and expensive part of the whole project, especially land transportation, the cost of which in most cases exceeded that of extraction21. Transporting blocks of stone via ravines and service roads was made easier by the concentration of quarries in wide quarrying zones, usually extending along the lower slopes of a region22. This arrangement apparently facilitated not only transportation but also the better organisation of the work, the allocation of personnel and the facilitation of the basic requirements for a quarry’s 17 For a full presentation of the laboratory results see Koukouvou 2012, pp. 207-218, and the relative Appendix, p. 335 ff. Current practice in provenance identification studies is to examine not only the marble but other stones as well, see the special section in the ASMOSIA congresses (e.g. ASMOSIA X, ASMOSIA XI, ASMOSIA XII). 18 Modern studies, e.g. Korres 1995; Bessac 1996, focus on the connection between the quarry and the construction site and underline the need for the research to move towards this direction. 19 For these inscription categories see Hellmann 2002, pp. 18-31. For the Epidaurian Tholos, see IG IV2, 103; Burford 1966; 1969; Koukouvou 2012, pp. 44-45, 53-54, note 64, 195-197. 20 IG II2, 1666. One of the architects of this work was Philon, the well known architect of the Naval Arsenal (Skeuotheke) in Piraeus, see Hellmann 2002, pp. 23-25. 21 For stone transportation methods in Antiquity see Wurch-Kozelj 1988. Kokkorou-Aleuras et al. 2010, pp. 5459. On the transportation of quarried stone from Asomata see Koukouvou 2012, pp. 197-198 (with bibl.). 22 This pattern was also used in regions such as Corinthia, Kleonai and Delphi, as mentioned earlier, see note 13. See also Koukouvou pp.110-115, p. 176 note 358, 198-200 with bibl. 126 A. Koukouvou Sc. Ant. operation23. In our case, the blocks extracted from the Asomata quarries were transported via the ravines crossing the region and the auxiliary roadways leading to the main road that skirted the mountain and connected Beroia with Aigeai via the river Haliakmon24. To judge from the extent of the quarrying and the testimonies of ancient sources, we can safely suggest that in certain regions with extensive evidence of extraction, such as the Corinthia, quarrying must have been a major activity with a vital impact on the life of the region25. In Classical and Hellenistic times, according the prevailing view, major building quarries were as a rule used for the construction of public works of religious or secular character. These quarries were owned and operated by the state and by sanctuaries. In the rare case where a quarry was leased, then the profits formed part of the city’s revenue. It has also been suggested, however, that in certain cases, especially when quarries were located within a city’s grid, as in Piraeus, the landowners were entitled to the exploitation of stone before building on their land. Unfortunately, in Macedonia we lack the written evidence that could inform us about the details of the design, organisation and execution of the construction works that changed the kingdom’s cities completely. Macedonia, certainly, displays essential differences from the citystates of southern Greece, for which we have certain information. The Macedonian king, during the period in question, that is the 4th century BC, had total control of the natural resources of his kingdom, and consequently of the administration and exploitation of its mineral wealth26. It has often been pointed out by scholars that Macedonia reshaped its urban landscape during the late Classical and early Hellenistic period, by implementing ambitious building projects. It was a time of prosperity and intense building activity in the kingdom’s major cities27. The erection of important public buildings in Pella, Aigeai, Mieza and elsewhere demanded very large quantities of poros, which was their main building material. Hence, even if the three excavated quarries around ancient Beroia were only a small part of the overall local quarry system, they are irrefutable witnesses of quarrying activity in this region of the Old Macedonian kingdom in the 4th century BC. It was an activity that changed the appearance of urban centres but also had a major impact on the shape and appearance of the countryside as well. It required the opening of many quarries, the construction of service roads, the installation of a sufficient number of workers and craftsmen on construction and quarry sites, the use of many draught animals and wagons for transportation, and provisions for the distribution of equipment, water and food to people and animals. An activity, that is, with various effects, economic and social. In recent years scholars seem to have better understood and assessed the experimentations and achievements of the Macedonian architectural programmes that managed the organisation 23 Such organisation would permit working in many areas without the different groups of quarrymen being ob‑ structed or the roads clogged with quarry by-products. See Marchand 2002, p. 339, note 175. 24 For the roads in the region see Koukouvou 2012, p. 133, no. 197 and p. 146, note 267. In Macedonia most cities were situated on the lower slopes of hills, while the main roadways ran at their base (Aigeai, Beroia, Mieza, Edessa). 25 It is plausible that certain itinerant groups of specialists, originating from places with an attested quarrying tradition, acted as mediators for the stone trade of their homelands and undertook the opening of new quarries and the extraction and shipment of the quarried stone, see Dworakowska 1977, pp. 9-10; Hellmann 2000; 2002, pp. 26, 71; Koukouvou 2012, pp. 199-201. For the supply of poros, see CID II: 34, col. I, l. 41. 62, col. II. A, l. 1. The building accounts of five important sanctuaries provide essential information for the craftsmen who worked in them during the Classical and Hellenistic period, see Feyel 2006, esp. pp. 341-368, for the distant geographical origin of artisans in these major building projects. 26 See Koukouvou 2012, pp. 204-205. 27 See note 13 in the present article. See also Drougou 1997; Lilimpaki-Akamati 1999, pp. 29-35; Kottaridi 2004, pp. 533-538; Saatsoglou-Paliadeli 2007. For the epigraphical evidence and also the historical and archaeological data that inform us about the development and organisation of the Macedonian cities in the 4th c. BC, see note 1 and Hatzopoulos 1999 (with bibl.). For the Macedonian cities and the development of public life see also Lilimpaki-Akamati 1999 and Koukouvou - Psarra 2011, pp. 233-235. 26.3, 2020 Building Cities in Macedonia 127 of complex spaces with selectivity and sophisticated original solutions. In a word, the role that Macedonia played as the starting point in shaping the new trends of Hellenistic architecture and, going further, the role that Macedonia played in the way the Western world built public spaces, palaces and privileged residences28. The ambitious Macedonian building programmes and their successful implementation presupposed a general openness to new ideas and an influential political will and purpose which could not have been devoid of ideological content. This willpower was expressed through another kind of army that was mobilised by the powerful Macedonian monarchs in a wholly different sphere. One must envisage an army of artists, craftsmen and workers devoted to new challenges, introduced in particular by Philip II, whose contribution to the development and reform of the civic units was enormous29. It would be a real godsend if we could chronicle the progress of the building work that transformed the Macedonian cities. Some idea of the process may be obtained from the inscriptions recording the construction accounts of important sanctuaries of the Greek world, such as Delphi, Delos, Epidaurus and Miletus, which are lively chronicles of the building works in progress30. For an idea of the harsh daily life of the humble workers who, with technical skill, supreme craftsmanship, passion and sheer hard work gave form and shape to the political will, the architectural conception and the artistic vision of other creative forces of their time, we have the evidence of the numerous inscriptions on broken pieces of pottery – ostraca – found in the Roman imperial granite quarries of Mount Claudianus in Egypt, which preserve a working diary of the 2nd century AD. On these sherds, written in ink or charcoal, we find lists of the number of craftsmen working in each quarry on a particular day, the sick and the reason for their absence (“three ill today, of whom one has dysentery”), references to the distribution of water, food, tools and equipment (e.g. ropes, pegs, wood), but also demands for repairs to the tools, especially for sharpening and reinforcing cutting tools. Of course, it goes without saying that we must bear in mind the differences in type and scale of the quarries we are discussing, in their management status (these were of the Roman Imperial period), and also of geographical and chronological distance. Nevertheless, the information we derive from these inscriptions is remarkably enlightening with regard to the operating conditions of the quarries and reveals a daily life probably not so different from that of the ancient Macedonian quarrymen31. In our opinion the most important finding is that all the sources make plain the high level of know-how, the careful planning, rational organisation and excellent management indisputably needed for smooth and successful quarrying32. In my view, this cannot be better expressed than by Manolis Korres, the expert in ancient quarrying activity: “A good quarryman would quite often bear in mind a few of the problems faced by the archi‑ tect, and made calculations which demanded considerable thought. He had to observe, evaluate, and handle a very difficult material. He had to comprehend complex combinations of geologi‑ 28 See indicatively Kopsacheili 2011 with bibl. Also Koukouvou - Psarra in the present volume. The public space of Macedonian cities crystallises in architectural form the crucial political and state changes that Philip II put forth during his reign and helps us comprehend the meaning of the speech Alexander the Great gave at Opis in Mesopotamia in 324 BC. (Arr. Anab. 7. 9. 2, transl. P. A. Brunt). For the decisive role of Philip II see Hatzopoulos 1997, esp. pp. 11-25; 1999; 2001, pp. 189-190; 2003, pp. 55-57, 64). See also Koukouvou - Psarra in this volume. 30 The accounts from the 2nd c. BC temple in Didyma of Miletus indicate the number of workers who quarried and rough-hewed the blocks, as well as the cost of feeding and clothing them and repairing their tools, see Hellmann 2002, pp. 23-26 with bibl. 31 For the ostraca from the quarries in Mons Claudianus see Bülow-Jacobsen 2009. For characteristic examples see ibid, pp. 16-17, no. 634-635 and pp.78-79, no. 725 (lists of personnel), pp. 68-69, no. 717 (mentions the sick personnel), pp. 125-126, no. 791 (letter mentioning the need for sharpening the tools). 32 See Waelkens - De Paepe-Moens 1988, pp. 92-93. Korres 1995, p. 179. 29 128 A. Koukouvou Sc. Ant. cal, geometrical, artistic and mechanical factors. Finally, all these factors had to operate within a perfectly organized system of work and production which in itself represented an exceptional intellectual undertaking. Unfortunately, this achievement has till today remained almost ignored since it is perceived as being neither artistic nor imbued with ideals… Why, therefore, should a great project be arbitrarily divided into higher intellectual and lower manual or “managerial” components?”33. Angeliki Koukouvou, Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki akoukouvou@culture.gr Bibliography ASMOSIA I 1988: N. Herz - M. Waelkens (eds.), Classical Marble: Geochemistry, Technology, Trade, Proceedings of the NATO Advanced Research Workshop on Marble in Ancient Greece and Rome (Ciocco-Lucca-Italy 1988), NATO ASI Series E, Applied Sciences, Vol. 153, Dordrecht-Boston 1988. ASMOSIA II 1992: M. Waelkens - N. Herz - L. Moens (eds.), Ancient stones: Quarrying, Trade and Provenance, Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference of Association for the Study of Marble and Other Stones in Antiquity (Leuven 1990); Monograph 4 of the Acta Ar‑ chaeologica Lovaniensia, Leuven University Press 1992. ASMOSIA III 1995: Y. Maniatis - N. Herz - Y. Basiakos (eds.), The Study of Marble and Other Stones Used in Antiquity, Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference of Association for the Study of Marble and Other Stones in Antiquity (Athens 1993), London 1995. ASMOSIA IV 1999: M. Schvoerer (ed.), Archeomateriaux – Marbres et Autres Roches, Pro‑ ceedings of the 4th International Conference of Association for the Study of Marble and Other Stones in Antiquity (Bordeaux-Talence 1995), Bordeaux 1999. ASMOSIA V 2002: J. Herrmann - N. Herz - R. Newman (eds.), Proceedings of the 5th International Conference of Association for the Study of Marble and Other Stones in Antiquity: Interdisciplinary Studies on Ancient Stone (Boston 1998), London 2002. ASMOSIA VI 2002: L. Lazzarini (ed.), Proceedings of the 6th International Conference of Association for the Study of Marble and Other Stones in Antiquity: Interdisciplinary Studies on Ancient Stone (Venice 2000), Padova 2002. ASMOSIA VII 2009: Y. Maniatis (ed.), Proceedings of the 7th International Conference of Association for the Study of Marble and Other Stones in Antiquity (Thassos-Greece 2003), BCH Suppl. 51, 2009. ASMOSIA VIII 2009: P. Jockey (ed.), Leukos Lithos. Marbres et autres roches de la Méditerranée antique: études interdisciplinaires, Proceedings of the 8th International Conference of Association for the Study of Marble and Other Stones in Antiquity (Aix-en-Provence 2006), Paris 2009. ASMOSIA IX 2012: A. Guitierrez Garcia-Moreno - P. Lapuente - I. Roda (eds.), Proceedings of the 9th International Conference of Association for the Study of Marble and Other Stones in Antiquity: Interdisciplinary Studies on Ancient Stone (Tarragona 2009) Tarragona 2012. 33 Korres 1995, pp. 7-8. 26.3, 2020 Building Cities in Macedonia 129 ASMOSIA X 2015: P. Pensabene - E. Gasparini (eds.), Proceedings of the 10th International Conference of Association for the Study of Marble and Other Stones in Antiquity (Rome 2012) Roma 2015. ASMOSIA XI 2018: D. Matetić Poljak - K. Marasović (eds.), Proceedings of the 11th International Conference of Association for the Study of Marble and Other Stones in Antiquity: Interdisciplinary Studies of Ancient Stone (Split 2015) Split 2018. ASMOSIA XII forthcoming: Proceedings of the 12th International Conference of Association for the Study of Marble and Other Stones in Antiquity: Interdisciplinary Studies of Ancient Stone (Izmir 2018), forthcoming. Andronikos 1989: M. Andronikos, Βεργίνα, οι βασιλικοί τάφοι και οι άλλες αρχαιότητες, Athens 1989. Andronikos et al. 1961: M. Andronikos - Ch. Makaronas - N. Moutsopoulos - G. Bakalakis, Το ανάκτορο της Βεργίνας, Αθήνα 1961. Bessac 1986: J.-C. Bessac, La prospection archéologique des carrières de pierre de taille: approche méthodologique, in Aquitania 4, 1986, pp. 151-171. Bessac 1996: J.-C. Bessac, La pierre en Gaule narbonnaise et les carrières du Bois des Lens (Nîmes): histoire, archéologie, ethnographie et techniques, JRA Suppl. Series 16, Ann Arbor (Mi‑ chigan) 1996. Burford 1961: A. Burford, Notes on the Epidaurian Building inscriptions, in BSA 61, 1961, pp. 275-281. Burford 1969: A. Burford, The Greek Temple Builders at Epidauros, Liverpool 1969. Domikos Lithos 2002: Ο δομικός λίθος στα μνημεία: Πρακτικά διεπιστημονικής ημερίδας (AthensMytilini 2001), Ινστιτούτο Γεωλογικών και μεταλλευτικών – Ελληνικό τμήμα ICOMOS, Athens 2002. Drougou 1992: S. Drougou, Βεργίνα: Το ιερό της Μητέρας των Θεών, in AErgoMak 6, 1992, pp. 45-49. Drougou 1997: S. Drougou, Das antike Theater von Vergina, in AM 112, 1997, pp. 281-305. Drougou 1999: S. Drougou, Βεργίνα 1999. Ο νέος τάφος του Heuzey (β), in AErgoMak 13, 1999, pp. 535-540. Dworakowska 1977: A. Dworakowska, Notes on the Terminology for Stones Used in Ancient Greece, in ArcheologiaWarsz 28, 1977, pp. 1-18. Faklaris 1996: P. Faklaris, Βεργίνα. Ο οχυρωτικός περίβολος και η Ακρόπολη, in AErgoMak 10, 1996, pp. 69-78. Feyel 2006: Ch. Feyel, Les artisans dans les sanctuaires grecques aux époques classique et hellénistique à travers la documentation financière en Grèce, BEFAR vol. 318, Athènes 2006. Ginouves - Martin 1985: R. Ginouves - R. Martin, Dictionnaire méthodique de l’architecture grecque et romaine, Roma 1985. Gounaropoulou - Chatzopoulos 1998: L. Gounaropoulou - M.B. Chatzopoulos, Επιγραφές Κάτω Μακεδονίας. Volume Α΄. Επιγραφές Βέροιας, Athens 1998. Hansen - Nielsen 2004: M.H. Hansen - T. Nielsen, An inventory of archaic and classical po‑ leis, Oxford 2004. Hatzopoulos 1996: M.B. Hatzopoulos, Macedonian Institutions under the Kings, A Historical and Epigraphic Study (MEΛETHMATA 22), Athènes 1996. Hatzopoulos 1997: M.B. Hatzopoulos, L’État macédonien antique: un nouveau visage, in Comptes rendus des séances de l’Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, 141e année, 1, 1997, pp. 7-25. Hatzopoulos 1999: M.B. Hatzopoulos, Η οργάνωση της Μακεδονίας κατά την εποχή του Μεγάλου Αλεξάνδρου, in Αλέξανδρος ο Μέγας: από τη Μακεδονία στην Οικουμένη, Proceedings of the congress (Beroia 1998), Beroia 1999, pp. 15-21. 130 A. Koukouvou Sc. Ant. Hatzopoulos 2003: M.B. Hatzopoulos, Polis, Ethnos and Kingship in Northern Greece, in K. Buraselis - K. Zoumboulakis (eds.), The Idea of European Community in History, Conference Proceedings, vol. II, Athens 2003, pp. 51-64. Hayward 2003: Ch.L. Hayward, The Geology of Corinth, The study of a basic resource, in Ch.K. Williams - N. Bookidis (eds.), Corinth, the Centenary 1896-1996, vol. XXX, Athens 2003, pp. 15-42. Hellmann 1992: M.-C. Hellmann, Recherches sur le vocabulaire de l’architecture grecque, d’après les inscriptions de Délos, Athènes 1992. Hellmann 2000: M.-C. Hellmann, Les déplacements des artisans de la construction en Grèce d’après les testimonia épigraphiques, in F. Blondé - A. Muller (eds.), L’artisanat en Grèce ancienne. Les productions, les diffusion, Actes du Colloque de Lyon (1998), Villeneuve d’Ascq, Uni‑ versité Charles de Gaulle-Lille 3, 2000, pp. 265-280. Hellmann 2002: M.-C. Hellmann, L’Architecture grecque, 1-Les principes de la construction, Paris 2002. Kefalidou 2009: E. Kefalidou, Ασώματα. Ένα αρχαϊκό νεκροταφείο στην Ημαθία, Thessaloniki 2009. Kokkorou-Aleuras et al. 2010: G. Kokkorou-Aleuras - E. Poupaki - A. Eustathopoulos, Αρχαία ελληνικά λατομεία, Athens 2010. Kopsacheili 2011: M. Kopsacheili, Hybridisation of Palatial Architecture: Hellenistic Royal Palaces and Governors’ Seats in A. Kouremenos - S. Chandrasekaran - R. Rossi (eds.), From Pella to Gandhara: Hybridisation and identity in the art and architecture of the Hellenistic East, Oxford 2011, pp. 17-34. Korres 1988: M. Korres, The Geological Factor in Ancient Greek Architecture, in P. Marinos G. Koukis (eds.), The Engineering Geology of Ancient Works. Monuments and Historical Sites, Proceedings of an International Symposium (Athens 1988) vols. I-III, Rotterdam 1988, pp. 17791793. Korres 1995: M. Korres, From Pentelicon to the Parthenon, Athens 1995. Kottaridou 1992: A. Kottaridou, Βεργίνα 1992, in AErgoMak 6, 1992, pp. 67-79. Kottaridou 1993: A. Kottaridou, Σωστικές ανασκαφές της ΙΖ΄ Εφορείας Προϊστορικών και Κλασικών Αρχαιοτήτων στη Βεργίνα, in AErgoMak 7, 1993, pp. 83-88. Kottaridi 2004: A. Kottaridi, Η ανασκαφή της ΙΖ΄ΕΠΚΑ στην πόλη και στη νεκρόπολη των Αιγών το 2003-2004: νέα στοιχεία για τη βασιλική ταφική συστάδα της Ευρυδίκης και το τείχος της αρχαίας πόλης, in AErgoMak 18, 2004, pp. 527-541. Koukouvou 1999: A. Koukouvou, Ανασκαφική έρευνα στον άξονα της Εγνατίας οδού: Νομός Ημαθίας, in AErgoMak 13, 1999, pp. 567-578. Koukouvou 2000: A. Koukouvou, Ανασκαφική έρευνα στον άξονα της Εγνατίας οδού: Ασώματα Βεροίας, in AErgoMak 14, 2000, pp. 563-574. Koukouvou 2001: A. Koukouvou, Ανασκαφική έρευνα στον άξονα της Εγνατίας οδού: Ασώματα Βεροίας, in AErgoMak 15, 2001, pp. 575-586. Koukouvou 2004: A. Koukouvou, Παλιομάννα Μέσης και Ασώματα Βέροιας: η έρευνα δύο νέων αρχαιολογικών θέσεων με αφορμή την κατασκευή του άξονα της νέας Εγνατίας οδού, in Γνωριμία με τη Γη του Αλεξάνδρου. Η περίπτωση του Νομού Ημαθίας. Ιστορία – Αρχαιολογία, Πρακτικά επιστημονικής Διημερίδας του Κέντρου Ιστορίας Θεσσαλονίκης (Thessaloniki 2003), Thessaloniki 2004, pp. 55-70. Koukouvou - Psarra 2011: A. Koukouvou - E. Psarra, Η αγορά της αρχαίας Μίεζας: Η δημόσια όψη μιας σημαντικής μακεδονικής πόλης, in Η Αγορά στη Μεσόγειο από τους ομηρικούς έως τους ρωμαϊκούς χρόνους, Πρακτικά διεθνούς επιστημονικού συνεδρίου (Cos 2011), Athens 2011, pp. 223-238. Koukouvou 2012: A. Koukouvou, Από τα λατομεία των Ασωμάτων Βέροιας στα οικοδομήματα των Μακεδόνων βασιλέων, Thessaloniki 2012. 26.3, 2020 Building Cities in Macedonia 131 Kouzeli 2007: K. Kouzeli, Λίθοι του ανακτόρου των Αιγών: φύση, κατάσταση διατήρησης, προτάσεις συντήρησης, in AErgoMak 21, 2007, pp. 149-156. Lilimpaki-Akamati 1999: M. Lilimpaki-Akamati, Μακεδονικές πόλεις, in Αλέξανδρος ο Μέγας: από τη Μακεδονία στην Οικουμένη, Πρακτικά διεθνούς συνεδρίου της Νομαρχιακής Αυτοδιοίκησης Ημαθίας (Beroia 1998), Beroia 1999, pp. 23-35. Marchand 2002: J.C. Marchand, Well-built Kleonai: a History of the Peloponnesian City, Ann Arbor-Michigan 2002. Bülow-Jacobsen 2009: A. Bülow-Jacobsen, Mons Claudianus. Ostraca Graeca et Latina IV. The Quarry-Texts (O.Claud. 632-896), Institut français d’archéologie orientale-Le Caire 2009. Orlandos 1958: A.K. Orlandos, Τα υλικά δομής των αρχαίων Ελλήνων, vol. 2, Athens 1958. Orlandos - Travlos 1986: A. Orlandos - I. Travlos, Λεξικόν αρχαίων αρχιτεκτονικών όρων, Athens 1986. Papageorgakis - Kolaiti 1992: J. Papageorgakis - E. Kolaiti, The ancient limestone quarries of Profitis Elias near Delfi (Greece), in M. Waelkens - N. Herz - L. Moens (eds.), ASMOSIA II, Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference of Association for the Study of Marble and Other Stones in Antiquity (Leuven 1990): Ancient stones: Quarrying, Trade and Provenance, Monograph 4 of the Acta Archaeologica Lovaniensia, Leuven University Press 1992, pp. 37-41. Papazoglou 1988: F. Papazoglou, Les villes de Macédoine à l’époque romaine, BCH Supp. XIV, Paris 1988. Röder 1971: J. Röder, Marmor Phrygium. Die antiken Marmobrüche von Ischhisar in Westanatolien, in JdI 86, 1971, pp. 253-312. Romaios 1953-54: K. Romaios, Το ανάκτορον της Παλατίτσας, in AEphem 1953-1954 (εις μνήμην Γ. Οικονόμου) I, pp. 141-150. Saatsoglou-Paliadeli 1992: Ch. Saatsoglou-Paliadeli, Βεργίνα 1992. Ανασκαφή στο ιερό της Εύκλειας (1982-1992). Σύντομος απολογισμός, in AErgoMak 6, 1992, pp. 51-57. Saatsoglou-Paliadeli 1996: Ch. Saatsoglou-Paliadeli, Το ιερό της Εύκλειας στη Βεργίνα, in AErgoMak 10, 1996, pp. 55-68. Saatsoglou-Paliadeli 2007: Ch. Saatsoglou-Paliadeli, Το ανάκτορο της Βεργίνας- Αιγών. Παρελθόν, παρόν και μέλλον, in AErgoMak 21, 2007, pp. 127-134. Waelkens - De Paepe - Moens 1988: M. Waelkens - P. De Paepe - L. Moens, Patterns of Extraction and Production in the White Marble Quarries of the Mediterranean: History, Present Problems and Prospects, in N. Herz - M. Waelkens (eds.), ASMOSIA I, Classical Marble: Geochemistry, Technology, Trade, Proceedings of the NATO Advanced Research Workshop on Marble in Ancient Greece and Rome (Ciocco-Lucca-Italy 1988), NATO ASI Series E, Applied Sciences, vol. 153, Dordrecht-Boston 1988, pp. 81-116. Wycherley 1974: R.E. Wycherley, Poros: Notes on Greek Building-Stones, in D. Bradeen M. Mc Gregor (eds.) Phoros, Tribute to B.D. Meritt, New York 1974, pp. 179-187. 132 A. Koukouvou Sc. Ant. Abstract Nel 2001 sono state portate alla luce tre antiche cave di poros vicino all’insediamento di Asomata, nella pre‑ fettura dell’Emathia (Macedonia, Grecia). Le cave di Asomata sono le prime cave di pietra da costruzione ad essere state scavate e studiate sistematicamente, non solo in Macedonia ma anche in Grecia. Il loro studio ha prodotto informazioni inestimabili sui metodi di estrazione e sugli strumenti utilizzati, nonché sul funzio‑ namento e l’organizzazione delle cave in età classica ed ellenistica. La loro ubicazione, che si colloca tra due importanti centri regionali: Aigeai, l’antica capitale macedone (l’attuale Vergina) e Beroia, ha sollevato un interrogativo sulla destinazione del materiale estratto. Per verificare la nostra ipotesi riguardo lo sfruttamen‑ to delle cave dell’Asomata per alimentare un importante programma edilizio che coinvolse la vicina Aigeai nel IV secolo a.C., generalmente priva di depositi di pietra da costruzione, è stato intrapreso un progetto di ricerca interdisciplinare. I risultati archeometrici confermano che i campioni delle cave di Asomata e quelli dei monumenti di Aigeai hanno evidenti somiglianze nella composizione mineralogico-petrografica, chimi‑ ca ed isotopica. Questo contributo si propone di presentare l’intensa attività di estrazione e costruzione in questa regione del regno macedone in un momento di prosperità e supremazia politica. Le cave oggetto di questo studio costituiscono così il collegamento tra i potenti committenti, ovvero i basileis che costruirono le grandi città del regno plasmando il nuovo volto della Macedonia ellenistica, con gli anonimi artigiani che con la loro conoscenza tecnica e competenza ingegneristica realizzarono i progetti dei loro sovrani.