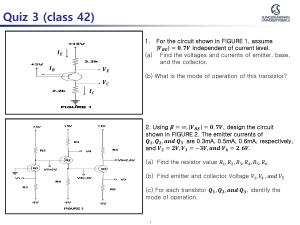

Bipolar Junction Transistors (BJTs): Device & Circuit Analysis

advertisement