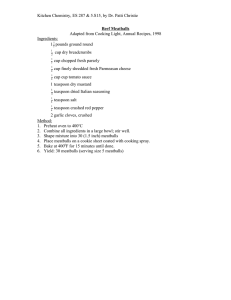

Wiley International Journal of Food Science Volume 2025, Article ID 2106508, 11 pages https://doi.org/10.1155/ijfo/2106508 Research Article Optimizing Young Jackfruit (Artocarpus heterophyllus Lam.) Processing for Plant-Based Meatballs: Impact of Thermal Treatments on Quality Parameters and Organoleptic Properties Wisutthana Samutsri and Sujittra Thimthuad Food Science and Technology Programme, Faculty of Science and Technology, Phranakhon Rajabhat University, Bangkok, Thailand Correspondence should be addressed to Wisutthana Samutsri; wisutthana@pnru.ac.th Received 1 August 2024; Accepted 11 December 2024 Academic Editor: Mitsuru Yoshida Copyright © 2025 Wisutthana Samutsri and Sujittra Thimthuad. International Journal of Food Science published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd. This is an open access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. As global demand for plant-based foods increases due to their nutritional and environmental benefits, young jackfruit (Artocarpus heterophyllus) is emerging as a promising meat alternative. This study evaluates the effects of heat treatments—specifically blanching for 5 min and boiling for 15, 30, and 45 min—on the quality and sensory attributes of jackfruit-based meatballs. The results indicate consistent color values (L∗ , a∗ , and b∗ ) across the samples, with L∗ values ranging from 53.68 to 54.92 and a∗ values from 3.02 to 3.38. The browning index increased with longer boiling times, while the water holding capacity improved from 2.22 to 4.35 as the cooking time extended. Blanching increased the hardness (536.93 g) and springiness (8.30%) of the meatballs. However, these properties decreased with longer boiling times, reaching 317.44 g and 7.68%, respectively, after 45 min. Sensory analysis revealed a strong preference for meatballs made from young jackfruit boiled for 45 min, with the highest score in appearance, flavor, and overall acceptability. These findings suggest that boiling young jackfruit for 45 min optimizes its texture and sensory qualities, highlighting its potential as a sustainable, nutritious, and appealing ingredient for plant-based meat substitutes. Keywords: heat treatment; meatball formulation; physicochemical properties; plant-based meat; sensory evaluation; young jackfruit 1. Introduction The global shift towards plant-based foods is intensifying due to their nutritional benefits, environmental sustainability, and consumer interest in alternative protein sources. As consumers become more health-conscious and environmentally aware, the demand for plant-based products has surged. Alternative meat products, valued at $4.6 billion in 2018, are projected to reach $85 billion by 2030 [1]. Furthermore, Sha and Xiong [2] estimate a market worth of $30.9 billion by 2026, underscoring rapid growth fueled by those following vegetarian or vegan lifestyles. Plant-based diets offer a viable route to meet nutritional needs while addressing ethical and environmental concerns surrounding traditional animal agriculture. Young jackfruit (JF) (Artocarpus heterophyllus) has gained considerable attention as a versatile meat alternative due to its unique fibrous texture and nutritional profile. This tropical fruit, originating in Western India and now cultivated in various regions, including Asia, Africa, and South America, is a sustainable option that requires minimal maintenance and thrives in diverse environments [3, 4]. Young JF is known for its meat-like texture, making it a popular choice for plantbased diets. It is high in fiber, low in calories, and rich in various vitamins and minerals [5]. The potential of JF as a meat substitute is further supported by its use in traditional dishes and its increasing popularity in modern culinary applications, such as pulled “pork” sandwiches and tacos [6]. Innovative processing methods have been explored to enhance the physicochemical properties of young JF-based meat analogues. For instance, recent research investigated the effects of drying methods, including tray drying and vacuum freeze drying, on chicken meat analogues made from young JF. The findings demonstrated that vacuum freeze drying at lower temperatures preserved superior sensory qualities [7]. The study by Mohammad and Nur [8] found that substituting fat with JF or breadfruit in low-fat chicken patties significantly enhanced water holding capacity (WHC), moisture, and protein levels while reducing fat content. Sensory evaluations indicated consumer preferences for the reformulated chicken patties. Overall, JF proves to be an effective and appealing fat substitute for healthier, low-fat patties. Furthermore, the fibrous structure of young JF contributes to its ability to mimic the texture of animal meat, making it an attractive ingredient for creating plantbased products such as meatballs [9, 10]. Plant-based products can deliver key health benefits, including high dietary fiber and essential vitamins, which can enhance physical performance and overall well-being. Meat alternatives with about 30% protein and low-fat content can effectively replace traditional meats [11]. Research indicates that plant-based meat alternatives can reduce metabolic risks linked to obesity and cardiovascular disease [12, 13] and exhibit anticancer, anti-inflammatory, and immune-enhancing properties [14]. Given these advantages, plant-based foods present a valuable option for consumers aiming to improve their health and physical performance. Beyond health, traditional livestock farming poses substantial environmental challenges, including greenhouse gas emissions and water pollution. Reducing meat consumption significantly lowers resource use and greenhouse gas output [15]. Reports indicate that components of plantbased meats generate far lower greenhouse emissions than conventional meats, although nutritional content and processing methods may vary [16]. The exploration of alternative raw materials continues, with research focusing on plant-based options that offer meat-like textures and robust nutritional profiles [5, 17–19]. Given the considerable volume of young JF left as waste—up to 120 fruits per mature tree, with only about 15 selected for consumption [4]—this study seeks to utilize young JF by-products to develop plant-based meatballs. Furthermore, the research will investigate how different heat treatments affect the physicochemical and sensory properties of these meatballs, optimizing JF processing for plantbased applications. 2. Materials and Methods 2.1. Materials. Three young Thai commercial “Thong Prasert” JFs (Artocarpus heterophyllus Lam.), approximately 7–11 weeks postflowering, with an average circumference of 45–55 cm, were sourced from a local market in Lopburi Province, Thailand, to serve as independent samples, with one JF used per experimental run. The JFs were categorized by maturity stages, with stage two, corresponding to 9 weeks postflowering, selected as per Konsue, Bunyameen, and Donlao [18]. Soy protein isolate and wheat gluten were obtained from Siam Modified Starch Co., Ltd. (Thailand), and citric acid was International Journal of Food Science Table 1: Physical characteristics of fresh young jackfruit. Characteristics Measurement Growth stage (weeks) Weight per fruit (g) Circumference (cm) Length (cm) Number of seeds per 2 ± 0 5 cm slice Yield (%) 7–11 2500–3000 45–55 60–70 8–10 42.8–44.0 sourced from Krungthepchemi Co., Ltd. (Thailand). Additional ingredients approved by the Thai FDA, including sugar, salt, vegetarian seasoning powder, garlic powder, ground pepper, and soybean oil, were sourced from a local market in Bangkok, Thailand. 2.2. JF Preparation. To prepare the young JF, the fruit was first thoroughly cleaned and sliced horizontally with 2 ± 0 5 cm thickness and 10 ± 2 cm diameter (Table 1). Each slice was soaked in a 0.3% w/v citric acid solution for 5 min to prevent oxidation. Heat processing was then applied to the sliced JF, with treatments including blanching for 5 min, followed by boiling for varied durations of 15, 30, and 45 min. After each heat treatment, the JF was immediately immersed in cold water (4° C ± 2° C) to stop further cooking. The cooled samples were then manually squeezed to remove excess water, cut into smaller pieces (approximately 3 ± 3 cm), and blended by using an electric blender (Philips Model HR2051/00/A, 450 W, 1.25 L capacity) at a speed level of 1 for 5 min to achieve a uniform consistency. Three uniformly treated JF samples were individually stored in sealed plastic containers at 4° C ± 2° C. A detailed flowchart for JF preparation is presented in Figure 1. 2.3. Plant-Based Meatball Production. The objective of this method was to determine the most suitable heating process for JF in the production of plant-based meatballs. Uniform JF mash from the initial processing stage was utilized to produce the meatballs, following the methodology outlined in Figure 2. Initially, 27 g of uniform JF mash from three different heating treatments (as described in Section 2.2) were equally combined with seasoning and stabilizing ingredients, including sugar, salt, vegetarian seasoning powder, garlic powder, ground pepper, and soybean oil, in the amounts specified in Table 2, according to the method described by Samutsri, Oumaree, and Thimthuad [20]. The mixture was kneaded in a double-arm kneading machine (TONG HOR machine Lex Product 0.85 kW, 0.5–6.0 kg/batch of capacity) for approximately 10 min to ensure thorough homogenization, after which it was manually formed into globularshaped meatballs with an approximate diameter of 2 5 ± 0 2 cm. These meatballs were then immersed in hot water at 60°C–65°C for 20 min for cooking. Once the meatballs floated to the surface, they were immediately removed from the warm water and transferred to cold water at 4° C ± 2° C for at least 10 s to halt the cooking process. Finally, the 1796, 2025, 1, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1155/ijfo/2106508 by Readcube (Labtiva Inc.), Wiley Online Library on [22/02/2025]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License 2 3 Peel & slice (i) Horizontally slice young jackfruit into circular pieces (1+0.2 inch thick, 10 cm diameter). Prevent oxidation (i) Soak slices in 0.3% w/v citric acid solution for 3 – 5 min. Heat treatment (i) Divide slices into 4 groups: blanch for 5 min. or boil for 15, 30, and 45 min. Mashed jackfruit preparation (i) Chop heat-treated slices into ~3 cm lengths. (ii) Blend using an electric blender. Figure 1: The preparation process of young jackfruit samples. Note: The flowchart was adapted with minor modifications from Samutsri, Oumaree, and Thimthuad [20]. Meshed JF Form the blend into meatballs. Heat in hot water until meatballs float, dunk meatballs in cold water Ingredients Mix the ingredients in a double-arm kneading machine for 3-5 min Mashed jackfruit (JF) and protein blends Figure 2: The production of plant-based young jackfruit (JF) meatballs. meatballs were stored in a plastic container in the refrigerator as the final product until further analysis. 2.4. Characterizations of Plant-Based Meatballs 2.4.1. Color Measurement. The color analysis of meshed JF paste and JF meatballs, subjected to three different heat treatments as detailed in Sections 2.2 and 2.3, was performed. For the mashed JF, three samples weighing 3 g each were prepared, resulting in a total of nine samples. The JF meatballs included one piece per treatment with three replicates each, also totalling nine samples. All 18 samples were placed in Petri dishes and sealed with single-use transparent plastic film to facilitate color readings with the colorimeter probe. Color evaluations were conducted using a colorimeter (Minolta, model CR-10, Japan), with readings taken from the surface of each sample. Assessments were performed in triplicate according to the method outlined by Maisont et al. [21]. The color parameters were reported in Commission Internationale de l'Éclairage (CIE) chromaticity coordinates: 1796, 2025, 1, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1155/ijfo/2106508 by Readcube (Labtiva Inc.), Wiley Online Library on [22/02/2025]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License International Journal of Food Science International Journal of Food Science Table 2: Formulation of young jackfruit-based plant-based meatballs in this study. Ingredients Content (g) Jackfruit Soy protein isolate Wheat gluten Sugar Salt Vegetarian seasoning powder Garlic powder Ground pepper Soybean oil Water 27.0 13.5 12.7 0.5 0.6 0.3 0.3 0.2 0.6 44.3 Note: Adapted from Samutsri, Oumaree, and Thimthuad [20]. lightness (L∗ ), redness (a∗ ), and yellowness (b∗ ). Lightness (L∗ ) ranged from 0 (black) to 100 (white). Redness (a∗ ) exhibited positive values for red undertones and negative values for green undertones, while yellowness (b∗ ) displayed positive values for yellow undertones and negative values for blue undertones. Water holding capacity = The colorimeter was calibrated using a standard white porcelain plate. Browning indexes (BIs) were calculated using the L∗ , a∗ , and b∗ values to assess color changes relative to the control meatball sample. The BI was computed using the following formula [22]: Browning index BI = 100 x − 0 31 0 172 where x = a∗ + 1 75 L∗ / 5 645 L∗ + a∗ − 3 012b∗ x = 5 645 × L∗ − 3 012 × b∗ . 2.4.2. WHC Measurements. WHC was analyzed according to the method of Dobson, Laredo, and Marangoni[23], with a modification to accommodate 2 g of sample mixed with 20 mL of distilled water in a 50-mL centrifuge tube. The slurry was allowed to stand for 10 min and then centrifuged at 6000 × g for 20 min. After centrifugation, the supernatant was drained, and the wet sample residue was weighed. The result was expressed as the amount of water the sample could hold. All samples were analyzed in triplicate. The WHC was calculated using the following equation: weight of hydrated sample − weight of sample weight of sample 2.4.3. Textural Measurements. Texture profile analysis (TPA) was performed on plant-based meatball samples subjected to various young JF processing treatments using a CTX Texture Analyzer (CTX50K, Brookfield, United States). Samples were positioned on a standard fixture on the analyzer table. Test conditions were as follows: Each sample underwent double compression with a TA36 probe (36 mm diameter flat cylinder) and a trigger force of 10 × g. The pre- test, test, and posttest speeds were set to 10, 1, and 10 mm/s, respectively, with a compression distance of 6 mm at ambient temperature. At least 10 replicates were measured per treatment. TPA curves were generated for each sample, and textural parameters including hardness, springiness, and chewiness were analyzed and defined according to established criteria [23, 24]. Hardness g = maximum peak force of the first compression Springiness % = ratio of maximum peak force of the first compression and maximum peak force of the second compression × 100 Chewiness = hardness × cohesiveness × springiness 2.5. Sensory Evaluation. The sensory evaluation for optimizing the plant-based meatball formulation involved assessing samples with different heat-treated young JF variations. Fifteen semitrained panellists aged 18–22, participated in individual booths within the sensory laboratory of the Food Science and Technology program at Phranakhon Rajabhat University. Panellists were instructed on using a sevenpoint hedonic scale to rate each attribute: appearance, color, taste, flavor, texture, and overall liking, where 1 represented “dislike extremely” and 7 represented “like extremely.” Data were analyzed using analysis of variance (ANOVA) with blocked randomization in Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) Statistics (Version 18.0). The final plant-based meatball formulation was selected based on these sensory results. 2.6. Statistical Analysis. All experiments were conducted in triplicate. Mean values and standard deviations were calculated for each set of results. A one-way ANOVA was 1796, 2025, 1, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1155/ijfo/2106508 by Readcube (Labtiva Inc.), Wiley Online Library on [22/02/2025]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License 4 5 (a) (b) (c) (d) Figure 3: Photographic representation of the appearance, color, and texture of 3 g of mashed young jackfruit on a Petri dish subjected to various heat treatments: blanched for (a) 5 min and boiled for (b) 15 min, (c) 30 min, and (d) 45 min, before color measurement analysis. Colour of JF paste at various heat durations 100 90 80 A B B B L⁎ a⁎ b⁎ value 70 60 50 40 30 NS 20 10 0 A BC AB C L⁎ a⁎ b⁎ ABC The color bar displays mean ± standard deviation values for each sample. Distinct letter groupings indicate statistically significant differences (p ≤ 0.05). NS The color bar displays mean ± standard deviation values for each sample. Letter groupings indicate statistically non-significant differences (p ≤ 0.05). Blanch 5 min Boil 15 min Boil 30 min Boil 45 min (a) BI of JF paste at various heat durations 160 Browning index (BI) 158 156.7 157.4 Boil 30 min Boil 45 min 156 154 152 150.6 152.5 150 148 146 Blanch 5 min Boil 15 min (b) Figure 4: (a) Color values and (b) calculated browning index of mashed jackfruit (JF) subjected to varying durations of heat treatment. performed using SPSS Statistics (Version 18.0) to assess differences among treatments. Significant differences between mean values (p ≤ 0 05) were determined using Duncan’s multiple range test. 3. Results and Discussions 3.1. Characteristics of Young JF. Young JF harvested in this study was selected during the second growth stage, from 1796, 2025, 1, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1155/ijfo/2106508 by Readcube (Labtiva Inc.), Wiley Online Library on [22/02/2025]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License International Journal of Food Science International Journal of Food Science Colour of JF meatball at various heat durations 100 90 80 L⁎ a⁎ b⁎ value 70 ns 60 50 40 30 ns 20 ns 10 0 L⁎ a⁎ b ⁎ nsThe color bar displays mean ± standard deviation values for each sample. Letter groupings indicate statistically non-significant differences (p ≤ 0.05). Boil 30 min Boil 45 min Blanch 5 min Boil 15 min (a) BI of JF meatball at various heat durations 154 151.6 Browning index (BI) 153 153 152.5 151.0 152 152 150.6 151 151 150 150 149 Blanch 5 min Boil 15 min Boil 30 min Boil 45 min (b) Figure 5: (a) Color values and (b) calculated browning index of plant-based meatballs made from jackfruit (JF) subjected to varying durations of heat treatment. Table 3: Average water holding capacity of plant-based meatballs made from young jackfruit at various heat treatment durations. Heating process Water holding capacity Blanch 5 min Boil 15 min Boil 30 min Boil 45 min 2 65 ± 0 25b 2 22 ± 0 71b 4 35 ± 1 59a 3 69 ± 1 01ab Note: Mean ± standard deviation values in the same column with different superscript letters are significantly different (p ≤ 0 05). Weeks 7 to 11, which corresponds to the optimal period for developing desirable physical and textural qualities for culinary applications (Table 1). At this stage, each fruit exhibited an average weight of 2500–3000 g, with a circumference of 45–55 cm and a length of 60–70 cm, as shown in Table 1. These size parameters are significant for both yield estimation and processing requirements. Each horizontal slice of young JF, approximately 1 ± 0 2 inches thick, contained an average of 8 to 10 seeds, which contributes to the textural profile important in product formulation. The usable flesh yield per fruit ranged from 1100 to 1284 g, representing 42.8%–44.0% of the total fruit weight. This yield percentage is particularly relevant for food processing applications, where maximizing edible portion is critical for commercial viability. These findings suggest that young JF, harvested within this specific growth window, offers a consistent and substantial yield of usable flesh, supporting its potential as a plantbased ingredient. The high flesh yield, coupled with uniform physical characteristics, underscores the fruit’s suitability for processed food products, aligning with consumer demand for plant-based alternatives. 1796, 2025, 1, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1155/ijfo/2106508 by Readcube (Labtiva Inc.), Wiley Online Library on [22/02/2025]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License 6 7 Table 4: Textural characteristics of plant-based meatballs made from young jackfruit under different heat treatment durations. Heating process Hardness (g) Blanch 5 min Boil 15 min Chewiness# Springiness (%) a 536 93 ± 43 32 a 8 30 ± 0 48 27 13 ± 2 48 b b 28 39 ± 3 50 ab 25 97 ± 3 21 b 25 06 ± 3 29 7 84 ± 0 26 445 20 ± 33 20 c Boil 30 min 380 43 ± 38 05 Boil 45 min d 7 97 ± 0 31 7 68 ± 0 26 317 44 ± 31 87 Note: Mean ± standard deviation values in the same column with different superscript letters are significantly different (p ≤ 0 05). # Mean ± standard deviation in the same column with different superscript letters is nonsignificantly different (p ≥ 0 05). (a) (b) (c) (d) Figure 6: The appearance of plant-based meatballs made with young jackfruit, each with a globular shape approximately 2.5 cm in diameter. Images include a cross-section to display the internal texture of samples subjected to different heat treatments: blanched for (a) 5 min and boiled for (b) 15, (c) 30, and (d) 45 min. 3.2. Formulation of Young JF-Based Plant-Based Meatballs. The formulation and processing of plant-based meatballs were optimized based on the sensory characteristics, as summarized in Table 2. Young JF was subjected to scalding or boiling at various times before being ground into a paste to produce the meatballs (Figure 3). In developing plant-based meatballs, various measures were implemented to ensure product consistency. Young JF was selected for its ability to mimic the texture of pork [25]. Typically, soy and its derivatives dominate meat substitutes; however, the inclusion of a mixture of wheat flour, corn flour, and powdered rice flakes provides a necessary fiber boost to maintain gastrointestinal health [26, 27]. Wheat gluten plays a crucial role in producing meat analogues, acting as both a binding agent and a structural component by forming fibrous textures under mechanical deformation [11, 27]. 3.3. Color and BI of Plant-Based Meatballs Made From Young JF. Various heat treatments, including blanching for 5 min and boiling for 15, 30, and 45 min, were applied to the JF. Significant differences (p ≤ 0 05) in color values of JF pastes were observed across the heat treatments (Figure 4(a)). The L∗ values ranged from 70.80 to 82.53, a∗ values ranged from 2.30 to 5.73, and b∗ values ranged from 9.93 to 14.20. The BI was lowest for blanched samples and increased with boiling time (Figure 4(b)), indicating the extent of the Maillard reaction and caramelization processes at higher temperatures. The color values of the meatballs showed no significant differences (p > 0 05) across heat treatments (Figure 5(a)), with average L∗ values ranging from 53.68 to 54.92, a∗ values ranging from 3.02 to 3.38, and b∗ values ranging from 14.18 to 16.04. The BI also demonstrated no significant changes (p > 0 05) (Figure 5(b)). Although the heat treatments significantly impacted the mashed JF color (Figure 4), the final meatballs exhibited consistent color values. This consistency suggests that the meatball matrix’s structure and composition mitigated the visual effects of browning, allowing the inherent qualities of JF to prevail in the final product. 3.4. WHC of Young JF-Based Plant-Based Meatballs. The WHC of the meatballs was significantly influenced by the heat treatments (p ≤ 0 05) (Table 3). Extended processing times led to higher WHC, attributed to the solubilization of pectin in young JF, which forms a gel-like structure capable of entrapping water [28]. This moisture retention is crucial for enhancing product juiciness and overall sensory experience, aligning with consumer expectations for desirable meat substitutes. 3.5. Textural Characteristics of Young JF-Based Plant-Based Meatballs. TPA is a technique used to simulate the biting actions of the mouth through a two-compression process [24]. This method involves using a device that measures the chewing mechanism by applying a pressure probe twice. This texture profile illustrates the relationship between force 1796, 2025, 1, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1155/ijfo/2106508 by Readcube (Labtiva Inc.), Wiley Online Library on [22/02/2025]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License International Journal of Food Science International Journal of Food Science Appearance 7 6 5 4 Overall acceptability Colour 3 2 1 0 Texture Flavour Taste Blanch 5 min Boil 15 min Boil 30 min Boil 45 min Figure 7: Radar chart of sensory evaluation scores for plant-based meatballs from young jackfruit under varying heat treatment durations. and time. Significant differences in texture profile characteristics are crucial for consumer acceptance. Achieving a balanced relationship between hardness, springiness, and chewiness is crucial for creating a texture that mimics traditional meat. This is particularly important for plant-based and imitation meat products that are aimed at replicating the eating experience of real meat, aligning with consumer expectations. Hardness is the force required to break or separate the food. This measurement is obtained by pressing the product between the molars or between the tongue and the roof of the mouth. The maximum pressure recorded during this process determines the hardness value of the sample [23]. Hardness significantly decreased with extended heating, from 536.93 g for blanched samples to 317.44 g for those boiled for 45 min (p ≤ 0 05) (Table 4). The observed effect is due to the heat extraction of the pectin structure in young JF, which serves as the primary structural component of meatballs. According to Saxena, Bawa, and Raju [29], JF is an excellent source of pectin. Consequently, the gel-like structure formed by pectin in the JF pulp reaches its peak when heated for an extended period, resulting in the lowest hardness value of the meatballs [28]. Moreover, this reduction correlates with increased moisture content, enhancing the tenderness of samples [30]. Silva et al. [31] reported that as the moisture content in the extrusion feed increased, the hardness of soy protein–based high-moisture meat analogues decreased. This finding supports the observation that higher levels of heating result in reduced hardness, which correlates with the increased WHC noted at elevated heating levels (as illustrated in Table 3). Springiness is defined as the rate at which a material returns to its shape after being pressed twice, measured by the distance between them. The results exhibited significant differences, with blanched meatballs showing the highest springiness values (8.30%), gradually declining with increased boiling time (p ≤ 0 05) (Table 4). This trend suggests that while short heat treatments can enhance the springiness of the meatball structure, prolonged boiling may lead to the extraction of structural components like pectin, which diminishes overall flexibility. The mechanical properties of plant fiber/soy protein adhesive composites mainly depended on the morphology of the plant fiber, the content of the main components of fiber, and the interfacial addition between plant fiber and protein adhesives [32]. As the heating level increased, the springiness of the young JF decreased due to its high WHC. This resulted in a loose and soft product that provided minimal resistance during the compression test. This observation aligns with the findings of Taikerd and Leelawat [33]. Chewiness is defined as the energy required to masticate food until it can be swallowed. The chewability of meatballs made with young JF subjected to different heat treatment durations was analyzed. The average values of chewiness showed no significant differences across treatments (p > 0 05) (Table 4), indicating that the formulations maintained consistent chewability despite variations in hardness and springiness. 3.6. Sensory Evaluation of Young JF-Based Plant-Based Meatballs. The sensory characteristics of the meatballs were evaluated based on the appearance of plant-based meatballs made from young JF. These meatballs underwent different heat treatments: blanched for 5 min and boiled for 15, 30, and 45 min, as illustrated in Figure 6. Based on the sensory evaluation results for each characteristic (Figure 7), meatballs made with young JF boiled for 45 min received the highest liking scores for appearance, 1796, 2025, 1, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1155/ijfo/2106508 by Readcube (Labtiva Inc.), Wiley Online Library on [22/02/2025]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License 8 9 (a) (b) (c) (d) Figure 8: Close-up photographs illustrating the internal characteristics, including texture, color, and fiber structure, of young jackfruitbased plant-based meatballs subjected to different heat treatments: blanched for (a) 5 min and (b) boiled for 15, (c) 30, (d) and 45 min. color, flavor, taste, texture, and overall satisfaction. The preference for these meatballs can be attributed to their nonfibrous texture, in contrast to those boiled for shorter durations, such as 30 min (Figure 8). This study evaluated the quality of meatballs made from young JF subjected to different heat treatments. Blanching for 5 min or boiling for 15, 30, and 45 min impacted their physical properties, including color (L∗ , a∗ , and b∗ values), texture characteristics (hardness, springiness, chewiness), and sensory quality. Color is a primary sensory attribute that influences the initial appeal of food products. In this study, while heat treatments significantly impacted the color values of JF pastes, the final meatball color remained consistent across treatments. This stability ensures a uniform product appearance, essential for consumer expectations of meat substitutes. Notably, meatballs made from young JF boiled for 15 min exhibited desirable color and flexibility. In contrast, the sensory evaluation revealed that panellists rated the meatballs boiled for 45 min as the best across all attributes. Longer boiling time enhances juiciness and tenderness by increasing WHC and reducing hardness; however, excessive boiling led to a decline in springiness, indicating a tradeoff between moisture retention and structural flexibility. Reduced hardness and springiness at higher WHC levels, which is a key sensory attribute, align with consumer preferences for moist and tender products. The study indicates that the optimizing heat treatment achieves a balance between improved juiciness and tenderness while maintaining acceptable texture and structural integrity, which meets sensory expectations for plant-based meat alternatives. Thus, meatballs made from young JF that were heat-treated by boiling for 45 min were chosen as the optimal product. 1796, 2025, 1, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1155/ijfo/2106508 by Readcube (Labtiva Inc.), Wiley Online Library on [22/02/2025]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License International Journal of Food Science 4. Conclusions This study evaluated the impact of varying heat treatment durations on the physicochemical and sensory attributes of young JF in plant-based meatball formulations. Heat treatments included blanching for 5 min and boiling for 15, 30, and 45 min to assess their effects on product quality. Results indicated that heating duration significantly influenced the color and BI of JF paste, though these changes did not persist in the final meatball product. Extended heating times improved WHC due to pectin extraction, forming gel-like structures that resulted in softer textures. Sensory evaluation showed that meatballs boiled for 45 min were preferred across all attributes—appearance, color, flavor, taste, texture, and overall acceptability—primarily due to reduced fibrousness. These findings offer valuable insights for optimizing processing conditions for JF-based products in the plantbased meat industry. Data Availability Statement The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author. Conflicts of Interest The authors declare no conflicts of interest. Funding This research was funded by Thailand Science Research and Innovation (TSRI) under the fundamental fund for basic research, fiscal year 2023. References [1] UBS Group AG and UBS AG, Annual Report 2019: Consolidated financial statements of UBS Group AG and UBS AG, 2019, Retrieved from https://www.ubs.com/investors. [2] L. Sha and Y. L. Xiong, “Plant protein-based alternatives of reconstructed meat; science, technology, and challenges,” Trends in Food Science and Technology, vol. 102, pp. 51–61, 2020. [3] T. K. Bose, Fruits of India: Tropical and Subtropical, T. K. Bose, Ed., Naya Prokash, Calutta, India, 2nd edition, 1985. [4] S. L. Jagadeesh, B. S. Reddy, L. N. Hegde, G. S. K. Swamy, and G. S. V. Raghavan, “Value addition in jackfruit (Artocarpus heterophyllus Lam.),” in Proceedings of the annual meeting of the ASABE, Portland, Oregon, 2006. [5] T. Sadhana, A. Pare, S. Bhuvana, and M. R. Jagan, “Effect of soy-jackfruit flour blend on the properties of developed meat analogues using response surface methodology,” International Journal of Pure and Applied Bioscience, vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 600– 610, 2019. [6] S. Suitcase, “The use of jackfruit in plant-based food innovation,” 2023, https://www.savorysuitcase.com/. [7] B. Leelawat and T. Taikerd, “Effect of drying methods and conditions on the physicochemical properties of young jackfruitbased chicken meat analogs,” ACS Food Science & Technology, vol. 4, no. 11, pp. 2682–2689, 2024. International Journal of Food Science [8] R. I. Mohammad and F. A. A. Nur, “Potential use of jackfruit (Artocarpus heterophyllus) and breadfruit (Artocarpus altilis) as fat replacers to produce low-fat chicken patties,” International Journal of Engineering & Technology, vol. 7, no. 4.14, pp. 292–296, 2018. [9] M. Elleuch, D. Bedigian, O. Roiseux, S. Besbes, C. Blecker, and H. Attia, “Dietary fibre and fibre-rich by-products of food processing: characterisation, technological functionality and commercial applications: a review,” Food Chemistry, vol. 124, no. 2, pp. 411–421, 2011. [10] S. K. Sharma, S. Bansal, M. Mangal, A. K. Dixit, R. K. Gupta, and A. K. Mangal, “Utilization of food processing byproducts as dietary, functional, and novel fiber: a review,” Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, vol. 56, no. 10, pp. 1647–1661, 2016. [11] K. Kyriakopoulou, B. Dekkers, and A. J. Van Der Goot, “Plantbased meat analogues,” in Sustainable Meat Production and Processing, C. M. Galanakis, Ed., pp. 103–126, Elsevier Academic Press, 2019. [12] W. J. Craig, “Nutrition concerns and health effects of vegetarian diets,” Nutrition in Clinical Practice, vol. 25, no. 6, pp. 613–620, 2010. [13] M. Wanezaki, T. Watanabe, S. Nishiyama et al., “Trends in the incidences of acute myocardial infarction in coastal and inland areas in Japan: the Yamagata AMI Registry,” Journal of Cardiology, vol. 68, no. 2, pp. 117–124, 2016. [14] T. Nakata, D. Kyoui, H. Takahashi, B. Kimura, and T. Kuda, “Inhibitory effects of soybean oligosaccharides and watersoluble soybean fibre on formation of putrefactive compounds from soy protein by gut microbiota,” International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, vol. 97, pp. 173–180, 2017. [15] J. Poore and T. Nemecek, “Reducing food’s environmental impacts through producers and consumers,” Science, vol. 360, no. 6392, pp. 987–992, 2018. [16] O. Edenhofer, R. Pichs-Madruga, Y. Sokona et al., Climate Change 2014: Mitigation of Climate Change: Contribution of Working Group III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, University Press, Cambridge, 2015. [17] D. Ghangale, C. Veerapandian, A. Rawson, and J. Rangarajan, “Development of plant-based meat analogue using jackfruit as a healthy substitute for meat,” The Pharma Innovation Journal, vol. SP-11, no. 8, pp. 85–89, 2022. [18] N. Konsue, N. Bunyameen, and N. Donlao, “Utilization of young jackfruit (Artocarpus heterophyllus Lam.) as a plantbased food ingredient: influence of maturity on chemical attributes and changes during in vitro digestion,” LWT, vol. 180, Article ID 114721, 2023. [19] M. D. Kristensen, N. T. Bendsen, S. M. Christensen, A. Astrup, and A. Raben, “Meals based on vegetable protein sources (beans and peas) are more satiating than meals based on animal protein sources (veal and pork)-a randomized cross-over meal test study,” Advances in Food and Nutrition Research, vol. 60, no. 1, Article ID 32634, 2016. [20] W. Samutsri, K. Oumaree, and S. Thimthuad, “Physicochemical characteristics and sensory preference of chicken ball with unripe jackfruit,” LWT-Food Science and Technology, vol. 189, Article ID 115489, 2023. [21] S. Maisont, W. Samutsri, A. Sansomboon, and P. Limsuwan, “Drying edible jellyfish (Lobonema smithii) using a parabolic greenhouse solar dryer,” Food Research, vol. 6, no. 6, pp. 165–173, 2022. 1796, 2025, 1, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1155/ijfo/2106508 by Readcube (Labtiva Inc.), Wiley Online Library on [22/02/2025]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License 10 [22] S. N. Subhashree, S. Sunoj, J. Xue, and G. C. Bora, “Quantification of browning in apples using colour and textural features by image analysis,” Food Quality and Safety, vol. 1, no. 3, pp. 221–226, 2017. [23] S. Dobson, T. Laredo, and A. G. Marangoni, “Particle filled protein-starch composites as the basis for plant-based meat analogues,” Current Research in Food Science, vol. 5, pp. 892–903, 2022. [24] K. G. F. Schreuders, M. Schlangen, K. Kyriakopoulou, R. M. Boom, and A. J. van der Goot, “Texture methods for evaluating meat and meat analogue structures: a review,” Food Control, vol. 127, Article ID 108103, 2021. [25] I. Paranagama, I. Wickramasinghe, D. Somendrika, and K. Benaragama, “Development of a vegan sausage with young green jackfruit, oyster mushroom, and coconut flour as an environmentally friendly product with cleaner production approach,” Journal of Microbiology, Biotechnology and Food Sciences, vol. 11, no. 4, Article ID e4029, 2022. [26] S. Bardosono and D. Sunardi, “Soy plant-based formula with fiber: From protein source to functional food,” World Nutrition Journal, vol. 4, no. S1, pp. 18–23, 2020. [27] S. Thakur, A. K. Pandey, K. Verma, A. Shrivastava, and N. Singh, “Plant-based protein as an alternative to animal proteins: a review of sources, extraction methods and applications,” International Journal of Food Science and Technology, vol. 59, no. 1, pp. 488–497, 2024. [28] M. H. H. Khan, M. M. Molla, A. A. Sabuz, M. G. F. Chowdhury, M. Alam, and M. Biswas, “Effect of processing and drying on quality evaluation of ready-to-cook jackfruit,” Journal of Agricultural Science and Food Technology, vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 19–29, 2021. [29] A. Saxena, A. Bawa, and P. Raju, “Jackfruit (Artocarpus heterophyllus Lam.),” in Postharvest Biology and Technology of Tropical and Subtropical Fruits, E. M. Yahia, Ed., pp. 275–299, Woodhead Publishing, 2011. [30] A. Szpicer, A. Onopiuk, M. Barczak, and M. Kurek, “The optimization of a gluten-free and soy-free plant-based meat analogue recipe enriched with anthocyanins microcapsules,” LWT, vol. 168, Article ID 113849, 2022. [31] A. M. M. Silva, F. S. Almeida, F. Koksel, and A. C. Kawazoe Sato, “Incorporation of brewer's spent grain into plant-based meat analogues: benefits to physical and nutritional quality,” International Journal of Food Science and Technology, vol. 59, no. 6, pp. 3870–3882, 2024. [32] Y. Wang, M. Wang, W. Zhang, and C. He, “Performance comparison of different plant fiber/soybean protein adhesive composites,” BioResources, vol. 12, no. 4, pp. 8813–8826, 2017. [33] T. Taikerd and B. Leelawat, “Effect of young jackfruit, wheat gluten and soy protein isolate on physicochemical properties of chicken meat analogs,” Agriculture and Natural Resources, vol. 57, pp. 201–210, 2023. 11 1796, 2025, 1, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1155/ijfo/2106508 by Readcube (Labtiva Inc.), Wiley Online Library on [22/02/2025]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License International Journal of Food Science