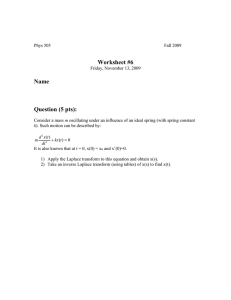

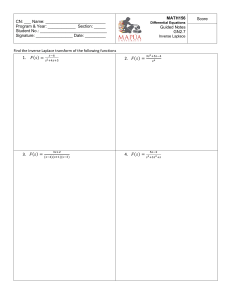

Engineering Applications of the Laplace Transform Engineering Applications of the Laplace Transform By Y.H. Gangadharaiah and N. Sandeep Engineering Applications of the Laplace Transform By Y.H. Gangadharaiah and N. Sandeep This book first published 2021 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2021 by Y.H. Gangadharaiah and N. Sandeep All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-7373-7 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-7373-4 CONTENTS Preface ......................................................................................................... x Chapter 1 ..................................................................................................... 1 The Laplace Transform 1.1 Introduction ...................................................................................... 1 1.2 Definition ......................................................................................... 3 1.3 Existence of Laplace Transforms ..................................................... 5 1.4 Laplace Transforms of Some Standard Functions ........................... 7 1.5 Operational Properties of the Laplace Transform .......................... 19 Property 1.5.1: Linearity of the Transform..................................... 20 Property 1.5.2: Transform of the Derivative .................................. 24 Property 1.5.3: First Translation Theorem ..................................... 27 Property 1.5.4: Multiplication of f t by t n .............................. 29 Property 1.5.5: Time-scaling .......................................................... 32 Property 1.5.6: Division by t ......................................................... 33 Property 1.5.7: Transforms of Integrals ......................................... 36 Property 1.5.8: The Initial-value Theorem ..................................... 38 Property 1.5.9: The Final-value Theorem ...................................... 41 1.6 Periodic Function ........................................................................... 52 1.6.1 Transform of a Periodic Function.......................................... 53 Contents vi 1.7 Second Shifting Theorem or Second translation Theorem ............ 68 1.7.1 Expression for Piecewise Continuous Function f t in Terms of the Unit Step Function .................................................... 70 Summary ............................................................................................ 105 Chapter 2 ................................................................................................. 107 The Inverse Laplace Transform 2.1 Introduction .................................................................................. 107 2.2 The Inversion Integral for the Laplace Transform ....................... 108 2.2.1 Relationship Between Laplace Transforms and Fourier Transforms ................................................................................... 109 2.2.2 Inversion Using the Bromwich Integral Formula ................ 112 2.3 The Inverse Laplace Transform is a Linear Transform ................ 114 2.4 Inversion Using the First Shift Theorem ...................................... 116 2.5 Inverse Transform by Differentiation and Integration ................. 119 2.6 Inversion Using the Second Shift Theorem ................................. 126 2.7 The Inverse Laplace Transform Using Partial Fractions.............. 128 2.7.1 Partial Fractions: Distinct Linear Factors ............................ 129 2.7.2 Partial Fractions: Repeated linear factors ............................ 153 2.7.3 Partial Fractions: Quadratic polynomials ............................ 163 2.8 Convolutions ................................................................................ 180 2.8.1 Definition ............................................................................ 180 2.8.2 Properties of Convolution ................................................... 180 2.9 Convolution Theorem .................................................................. 183 2.10 Integral and Integro-differential Equations ................................ 201 Summary ............................................................................................ 219 Engineering Applications of the Laplace Transform vii Chapter 3 ................................................................................................. 221 Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Transfer Functions 3.1 Introduction .................................................................................. 221 3.2 Transfer Functions ....................................................................... 223 3.3 Transfer Function of the Linear Time-invariant System .............. 225 3.3.1 Definitions: Linear and Nonlinear nth-order Ordinary Differential Equations............................................................. 226 3.4 Electrical Network Transfer Functions ........................................ 259 3.4.1 Kirchhoff’s Current Laws ................................................... 260 3.5 Mechanical System Transfer Functions ....................................... 280 Summary ............................................................................................ 290 Chapter 4 ................................................................................................. 292 Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Solving IVPS 4.1 Introduction .................................................................................. 292 4.2 The Scheme for Solving IVPs ...................................................... 294 4.2.1 Definitions: Homogeneous and Non-homogeneous Linear Differential Equations............................................................. 294 4.3 Differential Equations with Variable Coefficients ....................... 347 4.4 Total Response of the System Using the Laplace Transform ...... 361 4.4.1 Impulse Response and Transfer Function ........................... 362 4.5 Systems of Linear Differential Equations .................................... 370 Summary ............................................................................................ 389 Contents viii Chapter 5 ................................................................................................. 390 Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Electrical Circuits and Mechanical Systems 5.1 Introduction ................................................................................. 390 5.2 Application to Electrical Circuits ................................................. 390 5.2.1 The Scheme for Solving Electrical Circuits ........................ 390 5.3 Application to Mass-spring-damper Mechanical System ............ 430 Summary ............................................................................................ 453 Chapter 6 ................................................................................................. 454 Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: State-space Analysis 6.1 State-space Representation of Continuous-time LTI Systems ..... 454 6.2 State Model Representations........................................................ 455 6.2.1 Procedure to Find the Response of a Second-order Nonhomogenous System ............................................................... 457 6.3 Matrix Exponential (State-transition Matrix)............................... 458 6.3.1 Converting from State-space to Transfer Function ............. 459 Summary ...................................................................................... 489 Chapter 7 ................................................................................................. 490 Laplace Transform Methods for Partial Differential Equations (PDEs) 7.1 Introduction .................................................................................. 490 7.2 The Laplace Transforms of u x, t and its Partial Derivatives ................................................................................... 491 7.2.1 Steps in the Solution of a PDE by Laplace Transform ........ 494 Summary ............................................................................................ 521 Engineering Applications of the Laplace Transform ix Chapter 8 ................................................................................................. 522 Exercises and Answers Bibliography ............................................................................................ 537 PREFACE The Laplace transform, a technique of transforming a function from one domain to another, has a vital role to play in engineering and science. Laplace transformation methods offer simple and efficient strategies for solving many science and engineering problems, including: control system analysis; heat conduction; analyzing signal transport; mechanical networks; electrical networks; communications systems; and analog and digital filters. This book is aimed explicitly at undergraduates and graduates in applied mathematics, electrical and electronic engineering, physics, and computer science. The reader can follow the step by step problem solving and derivations presented with minimal instructor assistance. The first two chapters give a straightforward introduction to the Laplace transform, including its functional properties, finding inverse Laplace transforms by different methods, and the operating properties of inverse Laplace transform. Chapter 3 describes transfer function applications for mechanical and electrical networks to develop the input and output relationships. Chapters 4 and 5 demonstrate applications in problem solving, such as the solution of LTI differential equations arising in electrical and mechanical engineering fields, along with the initial conditions. The state-variables approach is discussed in Chapter 6 and explanations of boundary value problems connected with the heat Engineering Applications of the Laplace Transform xi conduction, waves, and vibrations in elastic solids are presented in Chapter 7. CHAPTER 1 THE LAPLACE TRANSFORM 1.1 Introduction Named in honor of the French mathematician Pierre Simon Laplace, the Laplace transform plays a vital role in technical approaches to studying and designing engineering problems. The significance of the Laplace transform is its application in many different functions. For example, the Laplace transform enables us to deal efficiently with linear constantcoefficient differential equations with discontinuous forcing functions— these discontinuities comprise simple jumps that replicate the action of a switch. Using Laplace transforms, we can also design a meaningful mathematical model of the impulse force provided by, for example, a hammer blow or an explosion. It is certainly not a lazy assumption to suggest that differential equations comprise the most important and significant mathematical entity in engineering and technology. The linear, time-invariant differential equation, Eq. (1), is one such design: N ¦ ak k 0 dk y t dt k M ¦ bk k 0 dkx t dt k (1) 2 Chapter 1 With the system parameters ܽ and ܾ , several systems are represented by this equation, which relates the output )ݐ(ݕ, to the input )ݐ(ݔ. However, we want to design a system where the state variables vary with time and/or space. The most natural way to describe this behavior is through differential equations. The development of a differential equation model requires a detailed understanding of the system we wish to depict. It is not enough to set up a differential equation model; we also have to solve the equations. Therefore, an essential mathematical method for modeling and analyzing linear systems is the Laplace transform. In terms of the mathematical representation of a physical system, the Laplace transform can simplify the study of its behavior considerably. The Laplace transform offers tremendous benefits. We model physical systems of continuous-time (linear time-invariant) when appropriate, with linear differential equations having constant coefficients. A clear explanation of the characteristics of the equations and physical structure is given by the Laplace transform of the LTI system. Once transformed, however, these differential equations are algebraic and are thus easier to solve. The solutions are functions of the Laplace transform variable ݏ rather than the time variable ݐwhen we use the Laplace transform to solve differential equations. Consequently, we will need a procedure to translate functions from the frequency domain to the time domain, which is called the inverse Laplace transform. In Section 1.3, we discuss the conditions under which a function’s Laplace transform occurs. In Section 1.4, we derive the Laplace transforms of standard signals as examples and present Laplace transform pairs in Table 1.1. In Section 1.5, various operational properties, i.e. linearity, timedomain shift rules, multiplication, division, and scaling practices, are The Laplace Transform 3 described. The regulations on differentiation and integration are presented in this section also. These are more difficult to demonstrate, but are of great importance in application. The time-domain differentiation rule is essential for applying the differential equations set out in chapters 3 and 4. We also deal with two theorems in this section, i.e. the initial and final value theorems for the Laplace transform. We can see how to evaluate the Laplace transform of a periodic function in Section 1.6. Section 1.7 explains how you can determine the Laplace transform of a piecewise continuous function that uses the unit step function. LEARNING OBJECTIVES On reaching the end of this chapter, we expect you to have understood and be able to apply: x The definition of the Laplace transform. x The concept of the existence of the Laplace transform. x The standard examples of the Laplace transform. x The properties of linearity, shifting, and scaling. x The rules of differentiation and integration. x The initial and final value theorems. x The Laplace transform of a periodic function. x How to express the piecewise continuous function in terms of the unit step function. 1.2 Definition f t is a real or complex-valued function of the (time) variable t ! 0 and s is a real or complex parameter. We define the Suppose that Laplace transform as Chapter 1 4 F s L^ f t ` f ³e st f t dt 0 where the limit exists as a finite number. (1.1) s is a fixed parameter (real/complex) when evaluating the integral (1.1). However, the reader should understand that, in advanced applications of Laplace transforms primarily to solve partial differential equations in digital signal processing, it is essential to consider s as a complex number. Before we proceed further, it is worth making a few observations relating to the definition in (1.1). i The Laplace transform is an integral transform. ii The Laplace transform only uses values of f t for t t 0. iii The symbol L denotes the Laplace transform operator. When it operates on the function f t , it transforms it into the function F s of the complex variable s . That is, the operator transforms the function f t in the t domain (time-domain) into the function F s in the s domain (complex frequency domain, or frequency domain). This relationship is depicted graphically in Figure 1.1. The Laplace Transform 5 Figure 1.1. The Laplace transform operator iv For the integral (1.1) to exist, any discontinuity of the integrand inside the interval 0, f must be a finite jump so that there are right and left-hand limits at those discontinuous points. An exception is a discontinuity at f t t 0 (if it exists). For instance, the function 1 diverges at t t 0 , but the integral (1.1) exists. v The Laplace transform is a mathematical toolbox for solving linear ODEs and related initial value problems, PDEs, and boundary value problems. It is used extensively in electrical engineering, control theory, and the stability of algorithms. 1.3 Existence of Laplace Transforms A Laplace transform should exist if the magnitude of the transform is finite, that is, F s f. Piecewise continuous: A function f t is piecewise continuous on a finite interval A d t d B if f is continuous on > A, B @ , except possibly Chapter 1 6 at many finite points. Each of these finite points f has a finite limit on both sides. Sufficient condition: The sufficient condition for a Laplace transform to exist if f t is that it is piecewise continuous on 0, f constants L and M and some f t M e Lt , then F s exist such that exists for s ! L . Proof: As f t is piecewise continuous on integrable on 0, f . L^ f t ` f f is f st st Lt st ³ f t e dt d³ f t e dt d³ M e e dt 0 M ª sL t ºf e ¼0 Ls ¬ L^ f t ` 0, f , f t e st 0 M >0 1@ Ls F s f Definition: A function f t positive constants T and M 0 M sL for s ! L. is said to be of exponential order L if exist such that f t M e Lt , for all t t T. The physical significance of the Laplace transform: A Laplace transform has no physical meaning except that it transforms the time domain function to a frequency domain s . The Laplace transform is The Laplace Transform 7 applied to simplify mathematical computations and allow the effortless analysis of linear time-invariant systems. 1.4 Laplace Transforms of Some Standard Functions In this section, we illustrate the procedure to find the Laplace transform of the function f t . In all expressions, it is assumed that f t satisfies the conditions of Laplace transformability. Example 1.1. Determine the Laplace transform of the constant function f t a. Solution: Using the definition of the Laplace transform F s L^ f t ` f ³e st f t dt 0 f L ^a` ³e st a dt 0 L ^a` a st f e 0 s L ^a` a f 0 ªe e º¼ s ¬ a >0 1@ s provided, of course, that s ! 0 (if s is real). Thus we have L ^a` a s s!0 . Chapter 1 8 Example 1.2. Find the Laplace transform of f t e at , where a is constant. Solution: By definition of the Laplace transform L^ f t ` F s f ³e st f t dt 0 ^ ` L e at f f at st ³e e d t ³e 0 s a t dt . 0 On integrating, we get L e at ^ ` 1 s a t f e 0 sa ^ ` 1 ª¬e f 1º¼ sa L e at Thus, ^ ` L e at 1 sa for s ! a Example 1. 3. Find the Laplace transform of f Solution: Let L ^ f t ` L >cosh at @ t cosh at. The Laplace Transform and express the function 9 cosh at in its exponential form 1 at at e e . 2 cosh at The Laplace transform becomes L^ f t ` 1 L ªe at e at ¼º 2 ¬ 1ª L e at L e at º¼ 2¬ ^ ` ^ ` 1ª 1 1 º « » 2 ¬« s a s a ¼» 1 ªs a s aº « ». 2 « s2 a2 » ¬ ¼ L > cosh at @ Thus, s s a2 L > cosh at @ 2 for s ! a . Example 1.4. Find the Laplace transform of f t sinh at. Solution: Let L ^f t ` L >sinh at @ and express the function cosh at sinh at 1 at e e at . 2 The Laplace transform becomes in its exponential form Chapter 1 10 1 L ¬ªe at e at ¼º 2 L >sinh at @ L >sinh at @ 1ª L e at L e at ¼º ¬ 2 ^ ` ^ ` 1ª 1 1 º « » 2 «¬ s a s a »¼ 1 ªs a s aº « » 2 « s2 a2 » ¬ ¼ Thus, L >sinh at @ a s a2 for s ! a . 2 Example 1.5. Find the Laplace transform of f t cos at. Solution: Let L ^ f t ` L >cos at @ and express the function cosh at in its exponential form 1 iat e e iat . 2 cosh at The Laplace transform becomes L^ f t ` 1 L ª¬eiat eiat º¼ 2 L > cosh at @ Thus, 1 ª iat L e L e iat º¼ ¬ 2 ^ ` ^ ` 1 ª s ai s ai º « ». 2 « s2 a2 » ¬ ¼ 1ª 1 1 º « » 2 «¬ s ia s ia »¼ The Laplace Transform L > cosh at @ s s a2 2 11 for s ! 0 . Example 1.6. Find the Laplace transform of f t sin at. Solution: Let L ^ f t ` L >sin at @ and express the function sin at in its exponential form sin at 1 iat iat . e e 2i The Laplace transform becomes L >sinh at @ 1 L ª¬eiat e iat ¼º 2i L >sinh at @ 1 ª s ia s ia º « » 2i « s 2 a 2 » ¬ ¼ 1ª 1 1 º « » 2 «¬ s ia s ia »¼ a . s a2 Thus, L >sinh at @ a s a2 2 for s ! 0 . 2 Chapter 1 12 Example 1.7. Find the Laplace transform of f t t n , where n is a positive integer. Solution: Using the definition of the Laplace transform F s f L^ f t ` ³e st f t dt 0 f ^ ` ³e L tn st tn d t Setting st x & dt 0 ^ ` L t n ^ ` L tn f §x· ³0 e ¨© s ¸¹ x 1 n dx s f s n 1 ³0 e x x n dx § Therefore, ¨ by gamma function * n © ^ ` L tn dx s f · x n 1 e x dx ¸ ³0 ¹ * n 1 s n 1 Thus, ^ ` L tn * n 1 s n 1 n! s n 1 * n 1 n! The Laplace Transform 13 Example 1.8. Find the Laplace transform of the Dirac delta function (impulse function) f G t . t Solution: An impulse is infinite at t 0 and zero elsewhere. The area under the unit impulse is 1. G t is defined by The Dirac delta function G t ­f ® ¯0 t 0 tz0 The Dirac delta function G t a is characterized by the following two properties i ­f ® ¯0 G t a t a tza f ii ³ G t a f t dt f a f Using the definition of the Laplace transform F s f L^ f t ` ³e st f t dt 0 L ^G t a ` f ³e st G ta dt 0 L ^G t a ` e st t a. Chapter 1 14 Thus, L ^G t a ` e as ^ t ` 1. and in particular L G Example 1.9. Find the Laplace transform of the unit step function f t u t . Solution: The unit step signal is a typical “engineering signal” in made to measure engineering applications, which often involve functions (mechanical or electrical driving forces). The unit step function u t is defined by u(t) 1 0 Figure 1.2. t u t ­1 ® ¯0 for t t 0 elsewhere The Laplace Transform 15 u(t – a) 1 0 t a ­1 ® ¯0 u t a for t t a elsewhere Figure 1.3 The step function is shown in Figure 1.2. The Laplace transform of u t , by definition, can be written as F s f L^ f t ` ³e st st u ta st dt f t dt 0 L^ u t a f ` ³e dt 0 L^ u t a f ` ³e a 1 st f e a s Hence, the Laplace transform of the unit step function exists only if the real part of s is greater than zero. We denote this by Chapter 1 16 ` 1 ª0 e as º¼ s ¬ . L^ u t a ` e a s , for s ! 0 s In particular L ^ u t ` 1s L^ u t a Thus, for a 0 . Example 1.10. Find the Laplace transform of the ramp function f t r t . Solution: The ramp function r t r t ­t ® ¯0 is defined by for t ! 0 f(t) for t 0 t Figure 1.4 The Laplace Transform 17 Using the definition of the Laplace transform, we have F s L^ f t ` f ³e st f t dt 0 L^ r t f ` ³e st r t st tdt dt 0 f L^ r t ` ³e 0 Recall from calculus the following formula for integration by parts b ³ u dv a b b uv a ³ v du. a f L^ r t ` f e st 1 t ³ e st dt . s 0 s0 Integration by parts gives L^ r t ` 0 1 st f e 0 s2 1 . s2 Thus, L^ r t ` 1 . s2 To further progress with the Laplace transform, it is necessary to use a table of Laplace transform pairs for the most commonly occurring functions. Table 1.1 provides a list of the most useful Laplace transform pairs involving elementary functions. Chapter 1 18 Table 1.1 Laplace Transform Pairs 1 s L tn ^ ` n! , n 1, 2,3....... s n 1 ^ ` s 1 a L e at ^ ` 1 sa s s a2 L ^1` L e at L ^sin at` a s a2 L ^cos at` L ^sinh at` a s a2 L ^cosh at` s s a2 L ^u t a ` e as s L ^u t ` 1 s L ^G t ` 1 2 2 2 2 L ^G t a ` e as Table 1.1 lists the Laplace transforms of some elementary functions. It would be helpful to familiarize yourself with these expressions. You will frequently encounter problems, solve linear differential equations with constant coefficients, find transfer functions, investigate mechanical systems, and analyze electrical circuits. The Laplace transform function can be derived directly by performing integration. However, it is much simpler to derive the Laplace transform using Laplace transform properties than through direct integration, as shown in the previous examples. The Laplace transform has many interesting operational properties. These properties are why the Laplace transform is considered such a powerful The Laplace Transform 19 tool of mathematical analysis. We will now derive these properties one after the other and apply them to generate more transforms, as illustrated in the next section. 1.5 Operational Properties of the Laplace Transform In Table 1.1 in the previous section, we presented an essential list of commonly occurring functions f t as Laplace transform pairs. It is necessary to establish several fundamental properties of the transform, known as its operational properties, to solve initial value problems of linear differential equations and deal with electrical and mechanical systems. The operational properties are those properties that directly relate to the way the transform operates on any function f t that is transformed, rather than the effect the properties have on specific functions. We will state and explain the various properties of Laplace transforms, including linearity, first translation, the multiplication of f t by t n , time-scaling, time integration, differentiation, initial value theorem, and final value theorem. Let us now consider their properties. Linear Operators An operator T is linear for every pair of functions f t and for every pair of constants C1 and C2. T ^C1 f t C2 g t ` C1T ^ f t ` C2T ^ g t `. and g t , Chapter 1 20 Differentiation and integration are both linear operations. For any two differentiable functions, f t and g t , and any two constants, C1 and C2, then d d d C1 f t C2 g t ` C1 ^ f t ` C2 ^ g t `. ^ dt dt dt Likewise, for any two integrable functions f t and g t , and any ^ ` two constants, C1 and C2, ³ ^C f t C g t ` dt 1 2 ^ ` C1 ³ f t dt C2 ³ g t dt . We now prove that the Laplace transform is a linear operator. Property 1.5.1: Linearity of the Transform The Laplace transform of a linear combination of two (or more) functions is equal to the linear combination of the respective Laplace transforms. Mathematically speaking, L ^C1 f t C2 g t ` C1 L ^ f t ` C2 L ^ g t ` . This linear property easily follows from the linearity property of integrals. Proof: The proof is simple and follows directly from the fact that the integration is a linear operation; as such, the integral of a sum of functions is the sum of their integrals. Thus, The Laplace Transform 21 f ³ e ^C f t C g t ` dt L ^C1 f t C2 g t ` st 1 2 0 ­ f st ½ ­ f st ½ C1 ® ³ e f t dt ¾ C2 ® ³ e g t dt ¾ ¯0 ¿ ¯0 ¿ C1 L ^ f t ` C2 L ^ g t ` and L ^C1 f t C2 g t ` C1 L ^ f t ` C2 L ^ g t `. The physical significance of the property of linearity: If the function can be decomposed into a linear combination of two or more component functions, then the Laplace transform of the function is the linear combination of the component functions. This simplifies the mathematical computations. Similarly, if the function can be decomposed into a linear combination of two or more component functions in the s domain, then the inverse Laplace transform of the signal is the linear combination of the component inverse Laplace transform functions. This property is used in the calculation of inverse Laplace transforms using partial fraction expansion. Example 1.11. Compute the Laplace transform of a 7 cos 2t 4t e4t c 7 t 4 . t b e2t 4e3t Chapter 1 22 Solution: a Using the values given in Table 1.1, L ^7` 7 , L ^cos 2t` s s , L ^t` s 4 2 1 & L ^e 4t ` 2 s 1 . s4 Using the linearity property of the Laplace transform, we find L ^7 cos 2t 4t e 4t ` L ^7` L ^cos 2t` 4 L ^t` L ^e 4t ` . Thus, L ^7 cos 2t 4t e 4t ` 7 s 4 1 2 2 . s s 4 s s4 b Using the values given in Table 1.1, L ^e 2t ` 1 & L ^e 3t ` s2 1 s3 Using the linearity property of the Laplace transform, we find L ^e 2t 4e 3t ` L ^e 2t ` 4 L ^e 4t ` L ^e 2t 4e 3t ` 1 1 . 4 s2 s3 Thus, L ^e 2t 4e 3t ` 3s 11 . s2 s 6 The Laplace Transform * n 1 and s n 1 c We have L ^t n ` * n 1 23 §1· n* n and * ¨ ¸ ©2¹ S (recurrence relation of gamma function) ­ 1½ L ®t 2 ¾ ¯ ¿ ­ L ®t ¯ 1 2 ½ ¾ ¿ §3· §1 · * ¨ ¸ * ¨ 1¸ ©2¹ ©2 ¹ 32 s s3 2 §1· *¨ ¸ ©2¹ s1 2 §1· *¨ ¸ 1 ©2¹ 2 s3 2 S S 12 s s 1 S 2 s3 2 Using the linearity property of the Laplace transform, we find 4½ ­ L ®7 t ¾ 7 L t¿ ¯ 4½ ­ L ®7 t ¾ t¿ ¯ ^ t ` 4L ­®¯ 1t ½¾¿ 7 S S 4 32 2s s Thus, 4½ ­ L ®7 t ¾ t¿ ¯ 7 S S 4 . 32 2s s Chapter 1 24 ^ t Example 1.12. Determine L m 7 cosh 2t 4t 100 e 11t ` . Solution: Using Table 1.1, ^ L ^mt ` L e log m t L ^t100 ` 100! s101 1 s , L ^cosh 2t` , ` s log m s 4 2 L ^e 11t ` & 1 s 11 Using the linearity property of the Laplace transform, we find L ^mt 7 cosh 2t 4t100 e 11t ` L ^mt ` 7 L ^cosh 2t` 4 L ^t100 ` L ^e 11t ` . Thus, L ^mt 7 cosh 2t 4t100 e11t ` 1 s 1 § 100! · . 7 2 4 ¨ 101 ¸ s log m s 4 © s ¹ s 11 Property 1.5.2: Transform of the Derivative If F s L^ f n t ` L ^ f t ` and f t is continuous for t t 0 then s n L ^ f t ` s n 1 f 0 s n 2 f 1 0 s n 3 f 11 0 ...... f n 1 0 . Proof: This property sheds light on why the Laplace transform is such a useful tool in solving initial value problems. Roughly speaking, using the Laplace transform, we can replace differentiation with respect to t and The Laplace Transform 25 multiplication by s, thereby converting a differential equation into an algebraic one. This idea is explored further in Chapter 4. For now, we show how this property can help to compute a Laplace transform. Let us start with the definition of the Laplace transform f ^ L f ' t ` ³e st f ' t dt 0 Integration by parts gives ^ ' L f t ` e st f t f 0 f s ³ e st f t dt 0 ^ L f ' t ` f f 0 s ³ e st f t dt 0 ^ L f 't ` f 0 sL ^ f t ` (1.2) This result can be easily extended to the second-order derivative; however, the first derivative f ^ L f '' t t must be continuous. Using Eq. (1.2), we have f ` ³e st f '' t dt 0 ^ L f '' t ` e st f' t f 0 f s ³ e st f ' t 0 ^ L f '' t ` f f ' 0 s ³ e st f ' t 0 ^ L f '' t ` f 0 s L ^ f t `. ' ' dt dt Chapter 1 26 ` f 0 s ^sL ^ f t ` f 0 ` . ^ L f '' t ' Thus, ^ ` s L^ f t ` s f 0 f 0 . L f '' t 2 ' According to the recursive nature of the Laplace transform of the nthderivative L^ f n t ` s n L ^ f t ` s n 1 f 0 s n 2 f Example 1.13. Given that L ^sin 2t` 1 0 s n 3 f 11 0 ...... f t sin 2t. Then f 0 0 and f ' t using the derivative property ^ L f 't ` f 0 s L^ f t ` L ^2 cos 2t` s L ^sin 2t` 2 L ^cos 2t` s 2 . s 4 2 Dividing by 2 gives L ^ cos 2t` s . s 4 2 0 . 2 , determine L ^cos 2t` . s 4 2 Solution: Let f n1 2 cos 2t , The Laplace Transform 27 Property 1.5.3: First Translation Theorem (First Shifting Theorem) If F s L ^e at f t ` L ^ f t ` and a is any real number, then F sa . Proof: The proof is immediate, since, by definition, L ^e f t ` at f st at ³ e e dt 0 L ^e at f t ` f ³e s a t dt 0 L ^e at f t ` F s a and L ^e at f t ` F s a . The above property states that if we know the Laplace transform of any function, the transform of that function multiplied by an exponential can immediately be obtained by a simple shift in the s variable. As the following example illustrates, this property allows us to easily calculate the Laplace transform of the function, e transform of f at f t , if we already know the t . ^ Example 1.14. Determine L e t cos 7t` . Solution: Using the values given in Table 1.1, Chapter 1 28 L ^cos 7t` s , s 49 F s 2 using the first shift theorem L ^et cos 7t` F s 1 s 1 F s s s 1 ^ 3 4t Example 1.15. Determine L t e 2 s 1 49 `. Solution: Using the values given in Table 1.1, L ^t 3 ` F s 6 , s4 by the first shift theorem L ^t 3e 4t ` F s 4 F s s s 6 In general, L ^e at cos bt` L ^e at cos bt` sa 2 s a b2 sa sa 2 b2 and 6 s4 2 . . The Laplace Transform b L ^e at sin bt` 2 s a b2 b L ^e at sin bt` 2 s a b2 sa L ^e at cosh bt` 2 s a b2 2 s a b2 b L ^e at sinh bt` 2 s a b2 b L ^e at sinh bt` 2 s a b2 n! sa n 1 n! L ^e at t n ` and sa L ^e at cosh bt` L ^e at t n ` and sa n 1 and and and . Property 1.5.4: Multiplication of f t by t n If F s L ^ f t ` and n 1, 2,3, 4..... , then L ^t n f t ` 1 n dn ª F s º¼ . ds n ¬ 29 Chapter 1 30 Proof: This property sheds light on why the Laplace transform is such a useful tool in solving initial value problems. Roughly speaking, we can use a Laplace transform to convert a function multiplied with t n into the s domain, thereby converting a differential equation with variable coefficients into an algebraic one. This idea is explored in Chapter 4. For now, we show how this property can help to compute a Laplace transform. Let us start with the definition of the Laplace transform F s L^ f t ` f ³e st f t dt 0 f ½° d n ­° st e f t d t ® ¾ ds n ¯° ³0 °¿ dn F s ds n Building on these assumptions, we can apply a theorem from advanced calculus (Leibniz’s rule) to interchange the order of integration and differentiation f dn F s ds n d n st ³0 ds n e ^ f t dt n e ts Using the nth-derivative i.e D d F s ds Thus, f ³e 0 st ^ t f t ` d t n n t e ts ` The Laplace Transform ^ L tn f t ` 1 n 31 dn F s ds n . Example 1.16. Determine L ^t sin 3t` . Solution: Using the values given in Table 1.1, L ^sin 3t` F s 3 s 9 2 using the multiplication theorem, L ^t sin 3t` d ª F s º¼ ds ¬ d § 3 · ¨ ¸ ds © s 2 9 ¹ 6s s2 9 2 . ^ e `. Example 1.17. Determine L t 2 3t Solution: Using Table 1.1, L ^e3t ` 1 s 3 F s using the multiplication theorem, L ^t 2 e3t ` 1 2 d2 ª F s º¼ ds 2 ¬ 1 d § 1 · ¨ ¸ ds ¨© s 3 2 ¸¹ 2 s 3 3 . Chapter 1 32 Property 1.5.5: Time-scaling If F 1 §s· F¨ ¸. a ©a¹ L ^ f t ` , then L ^ f at ` s Proof: Using the definition of the Laplace transform, F s L^ f t ` f st f t f at dt ³e dt 0 L ^ f at ` f ³e st 0 let at x dt dx a f §s· we get L ^ f at ` 1 ¨© a ¸¹ x e f x dx a ³0 . Thus, L ^ f at ` 1 §s· F ¨ ¸. a ©a¹ Example 1.18. Given that L ^sin t` L ^sin at` . F s 1 , determine s 1 2 The Laplace Transform 33 Solution: Let f t sin t and f at sin at , by the time-scaling property, L ^ f at ` 1 §s· F ¨ ¸. a ©a¹ L ^sin at` 1 1 a § s ·2 ¨ ¸ 1 ©a¹ Thus, L ^sin at` a . s a2 2 We have proved that differentiating the transform of a function corresponds to multiplying the function by t . Similarly, integrating the transform corresponds to dividing the function with t , as shown by the following theorem. Property 1.5.6: Division by t If F s ­f t ½ L ^ f t ` , then L ® ¾ ¯ t ¿ Proof: f By definition F s ³e 0 st f t dt. f ³ F s ds. s Chapter 1 34 Integrating both sides of the equation, f ff ³ F s ds ³³ e s st f t d t ds s 0 and reversing the order of integration, we get f ³ F s ds s f ª f st º ³0 «¬ ³s e ds »¼ f t d t (1.3) On integration, we get f f f ª e st º ³s F s ds ³0 «¬ t »¼ f t d t s (1.4) Thus, ­f t ½ L® ¾ ¯ t ¿ f ³ F s ds. s As before, the conditions on f (t ) and f (t ) / t have been introduced to guarantee uniform convergence. Only in this way can we be sure that the interchange of the order of integration in equation (1.3) and the operation of taking the limit under the integral sign in equation (1.4) are valid. ­ sin t ½ ¾. ¯ t ¿ Example 1.19. Determine L ® Solution: In this case, f t sin t , giving The Laplace Transform L ^sin t` F s 1 s 1 2 by the division theorem, ª f t º L« » ¬ t ¼ f f ³ F s ds ³ s 1 ds s ª sin t º 1 f L« tan s s ¬ t »¼ 1 2 s S tan 1 s. 2 Thus, ª sin t º S L« tan 1 s. » ¬ t ¼ 2 ­ e3t e 2t ½ ¾. t ¯ ¿ Example 1.20. Determine L ® Solution: In this case, f ^ L e3t e 2t t e3t e 2t , giving ` Fs 1 1 s 3 s 2 by the division theorem, ª f t º L« » ¬ t ¼ f f ³ F s ds ³ ¨© s 3 s 2 ¸¹ ds s s § 1 1 · 35 Chapter 1 36 ­ e3t e 2t ½ L® ¾ t ¯ ¿ f ^log s 3 log s 2 ` f s ­ ½ ª s 3 º° ° ®log « »¾ ° ¬ s 2 ¼° ¯ ¿s . Thus, ª s2 º ­ e3t e 2t ½ L® ¾ log « ». t s 3 ¯ ¿ ¬ ¼ Property 1.5.7: Transforms of Integrals If F t °­ °½ L ^ f t ` , then L ® ³ f W dW ¾ ¯° 0 ¿° s 1 L^ f t ` s Proof: t g t ³ f W dW 0 We have dg t dt f t and g 0 0 Taking Laplace transforms, ­ dg t ½ L® ¾ ¯ dt ¿ L^ f t ` sL ^ g t ` g 0 Hence, (using the derivative formula) L ^ f t `. F s s . The Laplace Transform L ^g t ` 37 1 L^ f t ` s giving the result ­° t ½° 1 L ® ³ f W dW ¾ L^ f t ` ¯° 0 ¿° s F s . Division of the transform of a function by s corresponds to integration of the function between the limits 0 and t . ­° t ½° 3W dW ¾ . Example 1.21. Determine L ® ³ sin 2W e °¯ 0 °¿ Solution: In this case, f ^ t L sin 2t e 3t sin 2t e 3t , giving ` Fs 2 1 s 4 s3 2 by the integral theorem, ­° t ½° 1 L ® ³ sin 2W e 3W dW ¾ F s ¯° 0 ¿° s 1§ 2 1 · ¨ 2 ¸. s © s 4 s3¹ In the analysis of a linear time-invariant (LTI) system, it is necessary to solve differential equations using Laplace transform techniques. Unfortunately, it is sometimes the case that it is impossible to invert F s to find the desired solution to the original problem. Numerical inversion techniques are possible and can be found in some software Chapter 1 38 packages, especially those used by the control system. Insight into the behavior of the solution can be deduced without actually solving the differential equation by examining the asymptotic character of F s for s or large s . In fact, it is often beneficial to determine this small asymptotic behavior without solving the equation, even when exact solutions are available, as these solutions are often complex and challenging to obtain, let alone interpret. In the next section, two properties help us to find the asymptotic behavior of the function. Property 1.5.8: The Initial-value Theorem The initial value theorem allows us to find the function’s initial value without finding the inverse Laplace transform. If F L ^ f t ` , then f 0 s Proof: We have the derivative formula ^ L f' t ` f 0 sL ^ f t ` f ³e st f ' t dt f 0 sF s . 0 Taking lim on both sides, we get sof 0 f 0 lim ^s F s ` . s of Therefore, lim ^s F s ` . s of The Laplace Transform 39 lim ^s F s ` . f 0 s of The initial value theorem’s physical significance: The initial value of the function can be found from its Laplace transform by taking the limit of s F s , as s tends to infinity. We need not take the inverse Laplace transform. Example 1.22. Determine the initial value of f t 5 sinh t . Solution: In this case f t L ^ 5 sinh t ` 5 sinh t , giving 5 s 2 s s 1 F s by the initial value theorem, ­ §5 s ·½ lim ® s ¨ 2 ¸ ¾ s of ¯ © s s 1 ¹¿ f 0 lim ^s F s ` f 0 s · § lim ¨ 5 2 2 ¸ s of s 1 ¹ © s of Thus, f 0 5. § s lim ¨ 5 2 s of ¨ s 1 1 s2 © · ¸ ¸ ¹ Chapter 1 40 Example 1.23. Using the Laplace transform, find the initial value of the function f t AeD t cos E t T u t . Solution: In this case, f t AeD t cos E t T u t . Using the trigonometric formula cos A B f t cos A cos B sin A sin B AeD t ^cos T cos E t sin T sin E t ` u t , giving L^ f t ` F s F s ^ ` ^ A cos T L eD t cos E t u t A sin T L eD t sin E t u t ª º ª º E s D T A cos T « A sin » « » 2 2 «¬ s D E 2 »¼ «¬ s D E 2 »¼ by the initial value theorem, f 0 lim ^s F s ` f 0 lim ^s F s ` s of s of ­ ½½ ° °­ ª cos T s D E sin T º °° lim ® s ® A « » ¾¾ 2 s of s D E 2 »¼ ¿°°¿ °¯ °¯ «¬ ­ ½ § D· E ° cos T ¨1 ¸ sin T ° ° ° s¹ s © A lim ® ¾. 2 2 s of § D· E ° ° ¨1 ¸ 2 °¯ °¿ s s © ¹ ` The Laplace Transform 41 Thus, A cos T . f 0 Property 1.5.9: The Final-value Theorem The final value theorem allows us to find the function’s final value without finding the inverse Laplace transform. If F L ^ f t ` , then f f s lim ^s F s ` . s o0 Proof: We have the derivative formula ^ L f' t ` f 0 sL ^ f t ` f ³e st f ' t dt f 0 sF s 0 Taking lim on both sides, we get so 0 f ' ³ f t dt 0 f f f 0 f 0 lim ^s F s ` s o0 f 0 lim ^s F s ` . Therefore, f f lim ^s F s ` . s o0 s o0 Chapter 1 42 The physical significance of the final value theorem: The final value of the function can be found from its Laplace transform by taking the limit of s F s , as s tends to zero. We need not take the inverse Laplace transform. Example 1.24. Determine the final value of f t 5 e 2t . Solution: In this case, f ^ L 5 e 2t t 5 e 2t , giving ` Fs 5 1 s s2 by the final value theorem, ­ §5 1 ·½ lim ® s ¨ ¸¾ s o0 ¯ © s s 2 ¹¿ f f lim ^s F s ` f f s · § lim ¨ s ¸ s o0 © s2¹. s o0 Thus, f f 0 · § lim ¨ 5 ¸ 5. s o0 © 02¹ Several operational properties of the Laplace transform have been developed. These properties are applied to generate Laplace transform tables and use the Laplace transform in the solution of linear differential equations with constant coefficients. These properties are applicable in The Laplace Transform 43 both the analysis and design of linear time-invariant physical systems. Table 1.2 gives the derived operational properties for the Laplace transform. Table 1.2 Basic Properties of the Laplace transform Linearity L ^C1 f t C2 g t ` C1 L ^ f t ` C2 L ^ g t ` Differentia tion in time Translation Multiplicat ion by t Time scale L ^ f n t ` s n F s s n 1 f L ^e at f t ` F sa L ^t dn 1 ^F s ` ds n n f t` L ^ f at ` n 1 §s· F¨ ¸ a ©a¹ Integration t °­ °½ 1 L ® ³ f W dW ¾ L^ f t ` °¯ 0 °¿ s Division by t ­f t ½ L® ¾ ¯ t ¿ Initial- f 0 lim ^s F s ` f f lim ^s F s ` value f ³ F s ds. s s of theorem Final-value theorem n 1 s o0 0 s n 2 f ' 0 ...... Chapter 1 44 Table 1.2 lists the operational properties of Laplace transforms. You should familiarize yourself with them, since they are frequently encountered in problems for solving initial value problems, finding transfer functions, and in the analysis of mechanical systems and electrical circuits. ^ Example 1.25. Determine L t e 2t sin 3t` . Solution: Using Table 1.1, L ^sin 3t` F1 s 3 s 9 2 using the multiplication theorem, F s L ^t sin 3t` d ª F1 s º¼ ds ¬ d § 3 · ¨ ¸ ds © s 2 9 ¹ 6s s2 9 and by the first shifting theorem, L ^e 2t t sin 3t` F s2 F s s s 2 ^ Example 1.26. Determine L t e Solution: Using Table 1.1, L ^cos t` F1 s s s 1 2 3t cos t` . 6 s2 s2 2 2 9 . 2 The Laplace Transform 45 using the multiplication theorem, L ^t cos t` F s d ª F1 s º¼ ds ¬ s2 1 d § s · ¨ ¸ ds © s 2 1 ¹ s2 1 2 and by the first shifting theorem, 2 L ^e t cos t` F s 3 F s s s 3 Example 1.27. Determine L ^ e t sin t` . 3t 8t s 3 1 2 2 . s 3 1 2 Solution: Using Table 1.1, L ^sin t` F1 s 1 s 1 2 using the multiplication theorem, F s L ^t sin t` 2 d ­d ½ ® ª¬ F1 s º¼ ¾ ds ¯ ds ¿ § · d ¨ s ¸ ds ¨ s 2 1 2 ¸ © ¹ 6s 2 2 s2 1 and by the first shifting theorem, 2 L ^ e t sin t` F s 8 8t 2 F s s s 8 6 s 8 2 2 s 8 1 3 . 3 Chapter 1 46 Example 1.28. Using the Laplace transform, find the initial and final values of the function f t 2e 3t e 4t . Solution: t 2e 3t e 4t giving F s L 2e 3t e 4t In this case, f L^ f t ` ^ ` ^by direct f 0 lim 2e e 3t t o0 F s 4 t 1 · § 2 ¨ ¸ © s3 s4¹ by the initial value theorem, ­ § 2 1 ·½ lim ® s ¨ ¸¾ s of ¯ © s 3 s 4 ¹¿ f 0 lim ^s F s ` f 0 ­§ ·½ 1 ¸ °° °° ¨ 2 lim ® ¨ ¸ ¾ 1. s of ° ¨ 1 3 s 4 ¸° s s ¹ ¿° ¯° © s of Thus, f 0 1. By the final value theorem, ` 1 The Laplace Transform 47 ­ § 2 1 ·½ lim ® s ¨ ¸¾ s o0 ¯ © s 3 s 4 ¹¿ f f lim ^s F s ` f f § · ¨ 2 1 ¸ lim ¨ ¸ s o0 ¨ 1 3 s 4 ¸ s s¹ © s o0 0. Thus, f f ^by direct f f lim 2e e 3t 0. t of 4 t `. 0 f Example 1.29. Evaluate ³e 2 t t 2 sin t dt . 0 Solution: Using Table 1.1, L ^sin t` 1 s 1 F1 s 2 using the multiplication theorem, F s L ^t 2 sin t` d ­d ½ ® ª F1 s º¼ ¾ ds ¯ ds ¬ ¿ § · d ¨ s ¸ ds ¨ s 2 1 2 ¸ © ¹ and by definition of the Laplace transform, f 2 t 2 ³ e t sin t dt 0 L ^t 2 sin t` s 2 ­ 2 ½ ° 6s 2 ° ® 2 3¾ °¯ s 1 °¿ s 2 22 . 125 6s 2 2 s2 1 3 Chapter 1 48 Thus, f ³e 2 t t 2 sin t dt 0 22 . 125 f e t e 3t ³0 t dt . Example 1.30. Evaluate Solution: We rewrite the integral as f et e3t ³0 t dt ^ § 1 e 2t · ³0 e ¨© t ¸¹ dt t t § 1 e 2t · ¨ ¸ , giving © t ¹ ` Fs 1 1 s s2 In this case f L 1 e 2t f by the division theorem, ª f t º L« » ¬ t ¼ ­1 e 2t ½ L® ¾ ¯ t ¿ Thus, f f ³ F s ds ³ ¨© s s 2 ¸¹ ds s §1 1 · s f ^log s log s 2 ` f s ­° ª s º ½° ®log « »¾ . ¯° ¬ s 2 ¼ ¿° s The Laplace Transform ­1 e 2t ½ L® ¾ ¯ t ¿ 49 ª s2 º log « ». ¬ s ¼ By definition of the Laplace transform, f 2 t · t § 1 e e ³0 ¨© t ¹¸ dt ­1 e 2t ½ L® ¾ ¯ t ¿s 1 ­° ª s 2 º ½° ®log « »¾ ¯° ¬ s ¼ ¿° s 1 log 3 thus, f 2 t · t § 1 e e ¨ ³0 © t ¸¹ dt log 3. ­ 2sinh 2t ½ ¾. t ¯ ¿ Example 1.31. Determine L ® Solution: In this case f ^ L e 2t e 2t t 2sinh 2t e 2t e 2t , giving 1 1 s2 s2 ` F s by the division theorem, ª f t º L« » ¬ t ¼ f f ³ F s ds ³ ¨© s 2 s 2 ¸¹ ds s ­ e 2t e 2t ½ L® ¾ t ¯ ¿ § 1 1 · s f ^log s 2 log s 2 ` e e f s ­° ª s 2 º ½° ®log e « »¾ . ¬ s 2 ¼ ¿° s ¯° Chapter 1 50 Thus, ª s2 º ­ 2sinh 2t ½ L® ¾ log e « ». s 2 ¯ t ¿ ¬ ¼ ­ 2t t Example 1.32. Determine L ®e ¯ 2W 0 Solution: Using the first shifting theorem, ­ 2t t 2W ½ L ®e ³ e cos 3W dW ¾ F s 2 ¯ 0 ¿ where F s ­ t 2W ½ L ® ³ e cos 3W dW ¾ ¯0 ¿ Using Table 1.1, L ^cos 3t` F2 s s s 9 2 by the first shifting theorem, L ^e 2t cos 3t ` s2 s2 by the integration property, 2 9 ½ ³ e cos 3W dW ¾¿ . The Laplace Transform s2 · 1§ ¨ ¸. s ¨© s 2 2 9 ¸¹ ­t ½ L ® ³ e 2W cos 3W dW ¾ ¯0 ¿ F s 51 Thus, ­ t ½ L ®e 2t ³ e 2W cos 3W dW ¾ F s 2 ¯ 0 ¿ f Example 1.33. Evaluate sin t ³ t s s 2 s2 9 dt . 0 Solution: Using Table 1.1, L ^sin t` F s 1 s 1 2 by the division theorem, ª f t º L« » ¬ t ¼ ­ sin t ½ L® ¾ ¯ t ¿ f f ³ F s ds ³ ¨© s 1 ¸¹ ds s ^tan s` 1 f s 1 § · 2 s S tan 1 s 2 and by definition of the Laplace transform, f ³e 0t 0 Thus, sin t dt t ­ sin t ½ L® ¾ ¯ t ¿s 0 ­S 1 ½ ® tan s ¾ ¯2 ¿s 0 S 2 . . Chapter 1 52 f ³e 2 t t 2 sin t dt 0 22 . 125 1.6 Periodic Function Intuitively, a function is periodic when it repeats itself. This intuition is captured in the following definition: a continuous-time function f t is periodic if there exists a positive real T for which f t T f t , t . The smallest such T is called the fundamental period of the function. i The square wave function in Figure 1.5 is periodic. The fundamental period of this square wave is T 4, but 8, 12, and 16 are also periods of the function. Figure 1.5. A periodic square wave function i A function that has period T will also have period 2T , 3T , etc. For example, the sine function has periods 2S , 4S , 6S etc. Some authors refer to the smallest period as the fundamental period or just the period of the function. The Laplace Transform 53 Periodic functions play a significant role in many branches of engineering and applied science, particularly control systems and circuit analysis. One only has to think of springs or alternating current in household electricity to understand their prevalence. Here, we introduce a theorem on the Laplace transform of periodic functions. We prove the theorem with a few illustrative examples. 1.6.1 Transform of a Periodic Function If f (t) is piecewise continuous on >0, f of the exponential order and periodic with a period T , then 1 1 e sT L^ f t ` T st ³ e f t dt . 0 Proof: Like many proofs of the operational properties of Laplace transforms, this one begins with its definition then evaluates the integral by using the periodicity of f L^ f t ` t . f ³e st f t dt 0 We write the Laplace transform of f T L^ f t ` t as two integrals f st st ³ e f t dt ³ e f t dt . 0 When we let t T u T , the last integral becomes Chapter 1 54 f f st ³ e f t dt ³e T f s u T f u T du 0 e sT ³ e su f u du e sT L ^ f t ` 0 . Therefore, T L^ f t ` ³e st f t dt e sT L ^ f t ` 0 T 1 e sT L ^ f t ` ³e st f t dt . 0 Thus, L^ f t ` 1 1 e sT T st ³ e f t dt. 0 The physical significance of the property of periodicity The Laplace transform of a periodic function can be found by taking the Laplace transform of one period and dividing it by is a period of the function. 1 e sT , where T The Laplace Transform 55 Example 1.34. Find the transform of the periodic function f t of the period T shown in Figure 1.6. f(t) K –2T 0 –T t 2T T Figure 1.6 Solution: The function f t is called a sawtooth wave and has a period T . For 0 t T. f t f t T can be defined outside the f t . The mathematical expression for f t period is f t interval K t 0dt dT T with f t T We have L^ f t ` L^ f t ` 1 1 e sT K T 1 e sT T st ³ e f t dt 0 T st ³ e t dt . 0 f t by in one- Chapter 1 56 Integrating by parts, we get L^ f t ` K ­ 1 st T 1 st T ½ te 2 e ¾ sT ® 0 0 s T 1 e ¯ s ¿ L^ f t ` K 1 ­ 1 ½ ª¬Te sT º¼ 2 ª¬e sT 1º¼ ¾ . sT ® s T 1 e ¯ s ¿ Therefore, L^ f t ` K s T 1 e sT 2 ^1 e sT sTe sT ` . Example 1.35. Find the transform of the periodic function f t of the period 2a shown in figure 1. 7. f(t) E t O a 2a 3a 4a –E Figure 1.7. A periodic square wave function Solution: The function f t is called a square wave and has a period T The mathematical expression for f t in one-period is 2a. The Laplace Transform f t ­E 0 d t d a ® ¯ E a d t d 2a 57 with f t 2a f t . We have L^ f t ` 1 1 e sT T st ³ e f t dt 0 L ª¬ f t º¼ 2a ª a st º 1 e E dt ³ e st E dt » s 2a « ³ 1 e a ¬0 ¼ L^ f t ` 2a ª a st º E st e dt e dt « ». ³ ³ 1 e s 2a ¬ 0 a ¼ After performing integration, L^ f t ` E s 1 e s 2a ^ e L^ f t ` E s 1 e s 2a ^ ª¬e Therefore, st a 0 sa e st 2a a ` ` 1º¼ ª¬e s 2 a e sa º¼ . Chapter 1 58 E e s 2 a 2e sa 1` s 2a ^ s 1 e L^ f t ` E 1 e sa u e L^ f t ` s 1 e sa ue sa 2 sa 2 E s 1 e sa § sa · E¨e 2 e 2 ¸ © ¹ sa sa § · s¨e 2 e 2 ¸ © ¹ sa 1 e sa 1 e sa § as · E sinh ¨ ¸ © 2¹. § as · s cosh ¨ ¸ © 2¹ Thus, E § as · tanh ¨ ¸ . s ©2¹ L^ f t ` Example 1.36. Determine the Laplace transform of the periodic function shown in Figure 1.8. f(t) 1 0 a 2a 3a 4a t 5a Figure 1.8. A periodic square wave function Solution: The function f t is called a square wave and has a period T The mathematical expression for f f t ­0 0 d t d a ® ¯1 a d t d 2a t in a one-period is with f t 2a f t 2a. 2 The Laplace Transform 59 We have L^ f t ` L^ f t ` 1 1 e sT T st ³ e f t dt 0 2a ª a st º 1 st e dt e dt 0 1 « ». ³ ³ 1 e s 2a ¬ 0 a ¼ On integrating, we get L^ f t ` 2a 1 st ª º e ¼a s 1 e 2 as ¬ 1 ªe 2 as e as º¼ s 2a ¬ s 1 e . Therefore, L^ f t ` 1 ªe as e 2 as º¼ 2 as ¬ s 1 e Thus, L^ f t ` e as . s 1 e sa e as s 1 e sa 1 e sa ª¬1 e as º¼ . Chapter 1 60 Example 1.37. Determine the Laplace transform of the half-wave rectifier shown in Figure 1.9. Figure 1.9. A periodic half-wave rectifier function Solution: The function f T t is called a half-wave rectifier wave and has a period 2S w . The mathematical expression for f t in one period is f t S ­ °°sin wt 0 d t d w ® 2S S °0 dt d °̄ w w § 2S · with f ¨ t ¸ w ¹ © We have L^ f t ` L^ f t ` 1 1 e sT T st ³ e f t dt 0 ­ Sw ½ 1 ° st ° ® ³ e sin wt dt ¾ . 2S s § ·°0 ° w ¨1 e ¸¯ ¿ © ¹ Recall from integral calculus that f t . The Laplace Transform at ³ e sin bt dt L^ f t ` L^ f t ` 61 eat ª a sin bt b cos bt º¼ a 2 b2 ¬ 1 e st s sin wt w cos wt 2S s § · 2 2 w ¨1 e ¸ s w © ¹ S s § · w w e 1 ¨ ¸ 2S s § · 2 ¹ 2 © w e s w 1 ¨ ¸ © ¹ S w 0 S s § · w ¨1 e w ¸ © ¹ S s S s § ·§ · 2 2 w w ¨1 e ¸¨1 e ¸ s w © ¹© ¹ Therefore, L^ f t ` § ¨1 e © S s w w . · 2 2 ¸ s w ¹ Example 1.38. Determine the Laplace transform of the full-wave rectifier shown in Figure 1.10. Figure 1.10. A periodic full-wave rectifier function Chapter 1 62 Solution: The function f T t is called a full-wave rectifier wave and has the period S w . The mathematical expression for f t f t sin wt 0 d t d S § S· with f ¨ t ¸ w © w¹ in one period is f t We have L^ f t ` L^ f t ` 1 1 e sT T st ³ e f t dt 0 ª Sw º 1 « st » e sin wt dt » . ³ S s « § · 0 w »¼ ¨1 e ¸ «¬ © ¹ On integrating, we get L^ f t ` L^ f t ` S 1 e st s sin wt w cos wt ` w ^ S s 0 § · 2 2 w ¨1 e ¸ s w © ¹ § ¨1 e © S s w § w ¨1 e · 2 2 © ¸ s w ¹ S s w · ¸ ¹ § Ss · w cosh ¨ ¸ © 2w ¹ . § Ss · 2 2 sinh ¨ ¸ s w © 2w ¹ The Laplace Transform 63 Therefore, L^ f t ` w § Ss · coth ¨ ¸. 2 s w © 2w ¹ 2 Example 1.39. Determine the Laplace transform of the rectified sine wave f t ­ sin t 0 t S with f t 2S ® ¯ sin t S t 2S f t . Solution: We have L^ f t ` L^ f t ` T 1 1 e sT st ³ e f t dt 0 1 1 e 2S s S 2S °­ st °½ sin e t dt e st sin t dt ¾ . ®³ ³ °¯ 0 °¿ S Recall from integral calculus that eat ª a sin bt b cos bt º¼ a 2 b2 ¬ at ³ e sin bt dt L^ f t ` L^ f t ` 1 1 e 2S s ^ªe s sin t cos t º¼ ª¬e s sin t cos t º¼ ` s 1 ¬ 2S s 2S st S 0 1 1 e S st 2 s2 1 ^ 1 e sS e s 2S e sS ` Chapter 1 64 L^ f t ` 1 e sS 1 e 2S s 2 s2 1 . Therefore, L^ f t ` L ª¬ f t º¼ 1 e sS 1 e sS s2 1 §Ss · sinh ¨ ¸ © 2 ¹ §Ss · s 2 1 cosh ¨ ¸ © 2 ¹ 1 §Ss · tanh ¨ ¸ . s 1 © 2 ¹ 2 Thus, L ª¬ f t º¼ 1 §Ss · tanh ¨ ¸. s 1 © 2 ¹ 2 Example 1.40. Determine the Laplace transform triangular wave shown in Figure 1.11. Figure 1.11. A periodic triangular-wave function The Laplace Transform 65 Solution: The function f period T f t t is called a triangular-wave rectifier wave and has the 2a. The mathematical expression for f t in one period is 0dt da ­t ® ¯ 2a t a d t d 2a with f t 2a f t We have L ª¬ f t º¼ L ª¬ f t º¼ T 1 1 e sT st ³ e f t dt 0 2a ª a st º 1 st e t dt e a t dt 2 « ». ³a 1 e s 2 a ¬ ³0 ¼ Integrating by parts, we get L ª¬ f t º¼ 1 ª1 e 2 as 2e as º¼ . s 1 e s 2a ¬ 2 Therefore, L ª¬ f t º¼ L ª¬ f t º¼ 1 2 s 1 e sa 1 e sa s 2 1 e sa 1 e sa 1 e sa 2 Chapter 1 66 L ª¬ f t º¼ § as · sinh ¨ ¸ © 2¹ § as · s 2 cosh ¨ ¸ ©2¹ 1 § as · tanh ¨ ¸ . 2 s ©2¹ Thus, L ª¬ f t º¼ 1 § as · tanh ¨ ¸ . 2 s ©2¹ Example 1.41. Determine the Laplace transform periodic function shown in Figure 1.12. f(t) 6 6 3t t 2 4 6 Figure 1.12 Solution: The mathematical expression for a given periodic function is f t We have ­3t ® ¯6 0dt d2 2dt d4 with f t 4 f t . The Laplace Transform L^ f t ` L^ f t ` 1 1 e sT 67 T st ³ e f t dt 0 4 ª 2 st º 1 st 3 6 e t dt e dt « ». ³2 1 e s 4 ¬ ³0 ¼ Integrating by parts, we get L^ f t ` ª ­ 3te st 3e st ½ 2 ­ 6e st ½ 4 º 1 «® 2 ¾ ® ¾ ». s ¿ 0 ¯ s ¿ 2 » 1 e s 4 « ¯ s ¬ ¼ Thus, L^ f t ` 3 1 e 2 s 2 se 4 s . s 2 1 e s 4 Example 1.42. Determine the Laplace transform of the half-wave rectifier f t periodic ­ °°sin T t ® °0 °̄ function 0t of the S T S 2S t T T . Solution: We have L^ f t ` 1 1 e sT T st ³ e f t dt 0 period 2S T defined by Chapter 1 68 L^ f t ` ª ST º 1 « st » e sin Tt dt » . ³ 2S s « § · 0 T »¼ ¨1 e ¸ «¬ © ¹ On integrating, we get L^ f t ` L^ f t ` ­ st 1 ®e s sin Tt T cos st 2S s § · ¯ 2 2 T ¨1 e ¸ s T © ¹ S s § · T T e 1 ¨ ¸. 2S s § · © ¹ 2 2 T ¨1 e ¸ s T © ¹ Therefore, L^ f t ` § ¨1 e © S s T T . · 2 2 ¸ s T ¹ 1.7 Second Shifting Theorem or Second Translation Theorem If F s L ^ f t ` and a ! 0, then L ^ f t a u t a ` e as L ^ f t ` . Proof: S T 0 ½ ¾ ¿ The Laplace Transform 69 The proof follows immediately from the definition of the unit step function. According to the definition of the Laplace transform, we have L^ f t ` f F s ³e st f t dt 0 L^ f t a u t a ` f st f t a u t a dt st f t a dt ³e 0 L^ f t a u t a ` f ³e a (1.5) In the last equation, we used the fact that u t a is zero for t a and equals 1 for t t a. Making the change of variable v t a , we have dv dt , and Eq. (1.5) becomes L^ f t a u t a ` f ³e s va f v dv a f L ^ f t a u t a ` e sa ³ e sv f v dv . a Therefore, L ^ f t a u t a ` e as F s . This establishes the theorem. Chapter 1 70 The only condition on f t is that it is a function that is of exponential order, which means that it is free from singularities for t ! a. The principal use of this theorem is that it enables us to determine the Laplace transform of a function that is switched on at time t a. 1.7.1. Expression for Piecewise Continuous Function f t in Terms of the Unit Step Function. Consider a piecewise continuous function f f t ­ f1 t ° ® f2 t ° ¯ f3 t t defined by 0dt a a dt b. t tb To construct the function f t , we can use the following ‘switching’ operations: (a) Switch on the function f1 t at t (b) Switch on the function 0; at t a , and, at the same time, f3 t at t b , and, at the same time, f2 t switch off the function f1 t ; (c) Switch on the function switch off the function f 2 t . In terms of the unit step function, f t may thus be expressed as The Laplace Transform f (t ) 71 f1 t ^ f 2 t f1 t ` u t a ^ f3 t f 2 t ` u t b Example 1.43. Obtain the Laplace transform of the piecewisecontinuous function shown in Figure 1.13 by expressing it in the unit step function. f(t) 3 1 2 t Figure 1.13 Solution: The function is continuous, but is defined differently on the intervals. As such, the mathematical expression for the function is f t 0 d t d1 ­0 ° ®3 t 1 1 t d 2 °3 tt2 ¯ Unit step functions for f t may be expressed as f (t ) f1 t ^ f 2 t f1 t ` u t a ^ f3 t f 2 t ` u t b f (t ) 3t 3 u t 1 6 3t u t 2 Chapter 1 72 Taking the Laplace transform, we have L ^ f (t )` L ^ 3t 3 u t 1 ` L ^ 6 3t u t 2 ` We cannot apply the second translation theorem with f t in this form since, according to the second translation theorem, for the first term we must have a function of t 1 and for the second term a function of t 2 . We can apply the second shifting property to the result above and obtain L ^ f (t )` e s L ^ f1 (t )` e2 s L ^ f 2 (t )` The function f (1.6) t is thus rewritten as follows. f1 (t 1) 3t 3 f 2 (t 2) replace t t 1 replace t 6 3t t2 f1 (t ) 3t f 2 (t ) 3t then its Laplace transform is then its Laplace transform is L ^ f1 (t )` 3 s2 Eq. (1.6) becomes 3 L ^ f 2 (t )` 2 s The Laplace Transform §3· §3· L ^ f (t )` e s ¨ 2 ¸ e2 s ¨ 2 ¸ ©s ¹ ©s ¹ 73 3 s 2 s e e . s2 Example 1.44. Obtain the Laplace transform of the piecewisecontinuous function shown in Figure 1.14 by expressing it in the unit step function. f(t) 3 0 –1 t 3 Figure 1.14 Solution: The function is continuous, but it is defined differently on the intervals. As such, the mathematical expression for the function is f t ­3 ° ® 5 2t ° ¯1 0 d t d1 1 t d 3 t t3 In terms of the unit step function, f t may be expressed as Chapter 1 74 f (t ) f1 t ^ f 2 t f1 t ` u t a ^ f3 t f 2 t ` u t b f (t ) 3 2 2t u t 1 2t 6 u t 3 Taking the Laplace transform, we have L ^ f (t )` L ^3` L ^ 2 2t u t 1 ` L ^ 2t 6 u t 3 ` . We cannot apply the second translation theorem with f t in this form, since, according to the second translation theorem, for the first term we must have a function of t 1 and for the second term a function of t 3 . We can apply the second shifting property to the result above to obtain L ^ f (t )` 3 s e L ^ f1 (t )` e 3 s L ^ f 2 (t )` s The function f (1.7) t is thus rewritten as follows. f1 (t 1) 2 2t f 2 (t 3) replace t t 1 replace t 2t 6 t 3 f1 (t ) 2t f 2 (t ) 2t then its Laplace transform is then its Laplace transform is L ^ f1 (t )` 2 s2 L ^ f 2 (t )` 2 s2 The Laplace Transform 75 Eq. (1.7) becomes L ^ f (t )` 3 s § 2 · 3s § 2 · 3 2 3s s e ¨ 2 ¸e ¨ 2 ¸ 2 e e . s ©s ¹ ©s ¹ s s Example 1.46. Express in terms of the Heaviside unit step function and find the Laplace transform of f (t ) ­t 2 0 d t d 2 . ® tt2 ¯4t Solution: In terms of the unit step function, f f (t ) t can be expressed as f1 t ^ f 2 t f1 t ` u t a f (t ) t 2 ª¬ 4t t 2 º¼ u t 2 Taking the Laplace transform, we have L ^ f (t )` ^ L ^t 2 ` L 4t t 2 u t 2 ` which, using the result in (1.7), gives L ^ f (t )` 2 2 s e L ^ f1 (t )` s3 (1.8) Chapter 1 76 f1 (t 2) t2 replace t f1 (t ) 4t t 2 4 t2 t2 2 f1 (t ) 4t 8 t 2 4t 4 f1 (t ) 4 t 2 then its Laplace transform is L ^ f1 (t )` 4 2 s s3 Eq. (1.8) becomes L ^ f (t )` 2 §4 2 · e 2 s ¨ 3 ¸ . 3 s ©s s ¹ Example 1.47. Find the Laplace transform for the function in Figure 1.15. Figure 1.15 The Laplace Transform 77 Solution: The function is continuous, but it is defined differently on the intervals. As such, the mathematical expression for the function is f (t ) ­0 ° ®sin t °0 ¯ 0dt dS S t d 3S t t 3S In terms of the unit step function, f f (t ) t can be expressed as f1 t ^ f 2 t f1 t ` u t a ^ f3 t f 2 t ` u t b f (t ) 0 sin t u t S sin t u t 3S . Taking the Laplace transform, we have L ^ f (t )` L ^sin t u t S ` L ^sin t u t 3S ` . We cannot apply the second translation theorem with f t in this form, since, according to the second translation theorem, for the first term we must have a function of t S and for the second term a function of t 3S . We can apply the second shifting property to the result above to obtain L ^ f (t )` eS s L ^ f1 (t )` e2S s L ^ f 2 (t )` The function f t is thus rewritten as follows. (1.9) Chapter 1 78 f1 (t S ) sin t replace t t S f 2 (t 3S ) sin t replace t t 3S f1 (t ) sin t S f1 (t ) sin t 3S f1 (t ) sin t f1 (t ) sin t then its Laplace transform is then its Laplace transform is L ^ f1 (t )` 1 s 1 2 L ^ f 2 (t )` 1 s2 1 Eq. (1.9) becomes § 1 · 2S s § 1 · L ^ f (t )` e S s ¨ 2 ¸e ¨ 2 ¸. © s 1 ¹ © s 1 ¹ Thus, L ^ f (t )` 1 e 2S s e S s . s 1 2 Example 1.48. Express in terms of the Heaviside unit step function ­1 ° and find the Laplace transform of f (t ) ®0 °sin t ¯ 0dt dS S t d 2S . t ! 2S The Laplace Transform 79 Solution: In terms of the unit step function, f f (t ) t can be expressed as f1 t ^ f 2 t f1 t ` u t a ^ f3 t f 2 t ` u t b f (t ) 1 u t S sin t u t 2S . Taking the Laplace transform, we have L ^ f (t )` L ^1` L ^u t S ` L ^sin t u t 2S ` We cannot apply the second translation theorem with f t in this form, since, according to the second translation theorem, for the first term we must have a function of t S and for the second term a function of t 2S . We can apply the second shifting property to the above result to obtain L ^ f (t )` 1 eS s 2S s e L ^ f1 (t )` s s The function f t is thus rewritten as follows. (1.10) Chapter 1 80 f1 (t 2S ) sin t replace t t 2S f1 (t ) sin t 2S f1 (t ) sin t then its Laplace transform is L ^ f (t )` 1 s2 1 Eq. (1.10) becomes L ^ f (t )` 1 e S s 2S s § 1 · e ¨ 2 ¸. s s © s 1¹ Example 1.49. Express in terms of the Heaviside unit step function and find the Laplace transform of f (t ) ­sin t 0 t d S 2 ® t !S 2 ¯cos t Solution: In terms of the unit step function, f f (t ) t can be expressed as f1 t ^ f 2 t f1 t ` u t a The Laplace Transform 81 § S· f (t ) sin t > cos t sin t @ u ¨ t ¸ . © 2¹ Taking the Laplace transform, we have L ^ f (t )` ­ § S ·½ L ^sin t` L ® cos t sin t u ¨ t ¸ ¾ © 2 ¹¿ ¯ which, using the result in (1.7), gives L ^ f (t )` S s 1 2 e L ^ f1 (t )` 2 s 1 The function f t is thus rewritten as follows. § S· f1 ¨ t ¸ © 2¹ Replace t cos t sin t t S 2 § S· § S· f1 (t ) cos ¨ t ¸ sin ¨ t ¸ © 2¹ © 2¹ f1 (t ) sin t cos t then its Laplace transform is 1 s L ^ f1 (t )` 2 2 s 1 s 1 (1.11) Chapter 1 82 Eq. (1.11) becomes L ^ f (t )` S s 1 s · § 1 e 2 ¨ 2 2 ¸. 2 s 1 © s 1 s 1 ¹ Example 1.50. Express in terms of the Heaviside unit step function and find the Laplace transform of f (t ) ­cos t 0 t d S . ® t !S ¯sin t Solution: In terms of unit step functions, f f (t ) t can be expressed as f1 t ^ f 2 t f1 t ` u t a f (t ) cos t >sin t cos t @ u t S . Taking the Laplace transform, we have L ^ f (t )` L > cos t @ L ^ sin t cos t u t S ` which, using the result in (1.7), gives L ^ f (t )` s eS s L > f1 (t )@ 2 s 1 The function f t is thus rewritten as follows. (1.12) The Laplace Transform f1 (t S ) replace t 83 sin t cos t t S f1 (t ) sin t S cos t S f1 (t ) sin t cos t then its Laplace transform is L ^ f1 (t )` s 1 2 s 1 s 1 2 Then, Eq. (1.12) becomes L ^ f (t )` s 1 · § s e S s ¨ 2 2 ¸ . s 1 © s 1 s 1¹ 2 Example 1.51. Express f t in terms of the Heaviside unit step function and find the Laplace transform f (t ) ­ 0 t 1 °2 ° 2 S °t 1 t ® 2 °2 S ° °¯cos t t ! 2 Chapter 1 84 Solution: In terms of unit step functions, f t can be expressed as f (t ) f1 t ^ f 2 t f1 t ` u t a ^ f3 t f 2 t ` u t b f (t ) ªt2 º ª t2 º § S · 2 « 2 » u t 1 «cos t » u ¨ t ¸ . 2¼ © 2¹ ¬2 ¼ ¬ Taking the Laplace transform, we have ­° ª t 2 º ½° ­° ª t 2 º § S · ½° L ^ f (t )` L ^2` L ® « 2 » u t 1 ¾ L ® «cos t » u ¨ t ¸ ¾ 2 ¼ © 2 ¹ °¿ °¯ ¬ 2 ¼ °¿ °¯ ¬ We cannot apply the second translation theorem with f t in this form, since, according to the second translation theorem, for the first term we must have a function of t 1 and for the second term a function of § S· ¨ t ¸. 2¹ © We can apply the second shifting property to the result above to obtain L ^ f (t )` Ss 2 s e L ^ f1 (t )` e 2 L ^ f 2 (t )` s The function f t is thus rewritten as follows. (1.13) The Laplace Transform f1 (t 1) t2 2 2 replace t t 1 S t2 f 2 (t ) cos t 2 2 replace t 2 t 3 t 2 2 f1 (t ) t S 2 t2 S 2 S f 2 (t ) sin t t 2 8 2 then its Laplace transform is then its Laplace transform is 1 1 3s s3 s 2 2 L ^ f1 (t )` 85 L ^ f 2 (t )` 1 1 sS 2 S s 2 1 s 3 8 2s 2 Eq. (1.13) becomes L ^ f (t )` 2 1 3s · S s § 1 1 sS 2 S · §1 e s ¨ 3 2 ¸ e 2 ¨ 2 3 2 ¸. s s 2 ¹ 8 2s ¹ ©s © s 1 s Example 1.52. Obtain the Laplace transform of the piecewisecontinuous function shown in Figure 1.16 by expressing it in the unit step function f(t) 1 t 1 Figure 1.16 2 3 4 Chapter 1 86 Solution: The function is continuous, but it is defined differently on the intervals. As such, the mathematical expression for the function is ­t ° f (t ) ®1 °0 ¯ 0 d t d1 1 t d 4 tt4 In terms of the unit step function, f f (t ) t can be expressed as f1 t ^ f 2 t f1 t ` u t a ^ f3 t f 2 t ` u t b f (t ) t 1 t u t 1 u t 4 . Taking the Laplace transform, we have L ^ f (t )` L ^t` L ^ 1 t u t 1 ` L ^u t 4 ` . We cannot apply the second translation theorem with f t in this form, since, according to the second translation theorem, for the first term we must have a function of t 1 and for the second term a function of t 4 . We can apply the second shifting property to the above result to obtain L ^ f (t )` 1 s e4 s e L ^ f1 (t )` s2 s (1.14) The Laplace Transform The function f 87 t is thus rewritten as follows. f1 (t 1) 1 t replace t t 1 f1 (t ) t then its Laplace transform is L ^ f1 (t )` 1 s2 Eq. (1.14) becomes L ^ f (t )` 1 e4 s s 1 e . s2 s Example 1.53. Express in terms of the Heaviside unit step function and find the Laplace transform of f (t ) ­cos t 0 t d S ° ®cos 2t S t 2S . °cos 3t t t 2S ¯ Solution: In terms of unit step functions, f f (t ) t can be expressed as f1 t ^ f 2 t f1 t ` u t a ^ f3 t f 2 t ` u t b Chapter 1 88 f (t ) cos t > cos 2t cos t @ u t S > cos 3t cos 2t @ u t 2S . Taking the Laplace transform, we have L > cos t @ L ^ sin t cos t u t S ` L > f (t ) @ L ^ cos 3t cos 2t u t 2S ` We cannot apply the second translation theorem with f t in this form since, according to the second translation theorem, for the first term we must have a function of t S and for the second term a function of t 2S . We can apply the second shifting property to the above result to obtain L ^ f (t )` s eS s L ^ f1 (t )` e2S s L ^ f 2 (t )` s 1 2 The function f f1 (t S ) replace t (1.15) t is thus rewritten as follows. cos 2t cos t t S f 2 (t 2S ) cos 3t cos 2t replace t t 2S f1 (t ) cos 2t 2S cos t S f 2 (t ) cos 3t cos 2t cos 2t cos t f 2 (t ) cos 3t cos 2t f1 (t ) then its Laplace transform is then its Laplace transform is The Laplace Transform s s 2 s 4 s 1 L ^ f1 (t )` 2 L ^ f 2 (t )` 89 s s 2 s 9 s 4 2 Eq. (1.15) becomes s 1 · s · § s § s e S s ¨ 2 2 ¸ e 2S s ¨ 2 2 ¸. s 1 © s 1 s 1¹ © s 9 s 4¹ L ^ f (t )` 2 Example 1.54. Express the signal shown in Figure 1.17 in terms of the Heaviside unit step function and find the Laplace transform. f(t) 1 t–1 3 –t t 1 2 3 4 Figure 1.17 Solution: The mathematical expression for the above function is Chapter 1 90 f t 0 d t 1 ­0 ° ° t 1 1 d t 2 ® 2dt 3 ° 3t °0 t t3 ¯ . In terms of unit step functions, f f (t ) t can be expressed as f1 t ^ f 2 t f1 t ` u t a ^ f3 t f 2 t ` u t b ^ f t f t `u t c 4 f (t ) 3 t 1 u t 1 4 2t u t 2 t 3 u t 3 . Then, taking Laplace transforms, L ^ f (t )` L ^ t 1 u t 1 ` L ^ 4 2t u t 2 ` L ^ t 3 u t 3 ` We cannot apply the second translation theorem with f t in this form, since, according to the second translation theorem, for the first term we must have a function of t 1 , for the second term a function of t 2 , and for the third term a function of t 3 . The Laplace Transform 91 We can apply the second shifting property to the above result to obtain L ^ f (t )` e s L ^ f1 (t )` e2 s L ^ f 2 (t )` e3s L ^ f3 (t )` The function f (1.16) t is thus rewritten as follows. f1 (t 1) t 1 f 2 (t 2) replace t t 1 replace t 4 2t t2 f3 (t 3) replace t t 3 t 3 f1 (t ) t f 2 (t ) 2t f 2 (t ) t then its Laplace then its Laplace then its Laplace transform is transform is transform is L ^ f1 (t )` 1 s2 L ^ f 2 (t )` 2 s2 Eq. (1.16) becomes L ^ f (t )` 1 s e 2e2 s e3s . 2 s L ^ f3 (t )` 1 s2 Chapter 1 92 Example 1.55. Express the function shown in Figure 1.18 in terms of the Heaviside unit step function and find the Laplace transform. Figure 1.17 Solution: The function is continuous, but is defined differently on the intervals. As such, the mathematical expression for the function is ­0 ° f (t ) ® t 1 °4 ¯ 0dt d2 2t d3 t t3 In terms of the unit step function, f t can be expressed as f (t ) f1 t ^ f 2 t f1 t ` u t a ^ f3 t f 2 t ` u t b f (t ) t 1 u t 2 t 3 u t 3 . The Laplace Transform 93 Taking the Laplace transform, we have L ^ f (t )` L ^ t 1 u t 2 ` t 3 L ^u t 3 ` . We cannot apply the second translation theorem with f t in this form, since, according to the second translation theorem, for the first term we must have a function of t 2 and for the second term a function of t 3 . We can apply the second shifting property to the above result to obtain L ^ f (t )` e2 s L > f1 (t )@ e3s L > f 2 (t )@ The function f (1.17) t is thus rewritten as follows. f1 (t 2) t 1 f 2 (t 3) replace t t2 replace t t 3 t 3 f1 (t ) t 1 f 2 (t ) t 6 then its Laplace transform is then its Laplace transform is L ^ f1 (t )` 1 1 s2 s Eq. (1.17) becomes L ^ f 2 (t )` 1 6 s2 s Chapter 1 94 § 1 1· § 1 6· L ^ f (t )` e2 s ¨ 2 ¸ e3s ¨ 2 ¸ . ©s s¹ ©s s¹ Example 1.56. Evaluate the Laplace transform of f (t ) sin E t u t T . Solution: Given f (t ) sin E t u t T , taking the Laplace transform, L ^ f (t )` L ^sin E t u t T ` which, using the result in (1.7), gives L ^ f (t )` eTs L ^ f1 (t )` f1 t T replace t sin E t t T f1 (t ) sin E t E T f1 (t ) sin E t cos E T cos E t sin E T then its Laplace transform is § E · § s · L ^ f1 (t )` cos E T ¨ 2 sin E T ¨ 2 2 ¸ 2 ¸ ©s E ¹ ©s E ¹ (1.18) The Laplace Transform 95 Eq. (1.18) becomes L ^ f (t )` ­ § E · § ·½ s sin E T ¨ 2 e Ts ®cos E T ¨ 2 2 ¸ 2 ¸¾ ©s E ¹ © s E ¹¿ ¯ Thus, L ^ f (t )` ^E cos E T s sin E T ` e . Example 1.57. f (t ) Ts 2 s E ­ °°0 ® °sin 3t 2 °̄ 2 Evaluate the Laplace transform 2 3 . 2 tt 3 t Solution: In terms of the unit step function, f f (t ) t can be expressed as f1 t ^ f 2 t f1 t ` u t a § 2· f (t ) sin 3t 2 u ¨ t ¸ . © 3¹ Taking the Laplace transform, we have L ^ f (t )` ­ § 2 ·½ L ®sin 3t 2 u ¨ t ¸ ¾ © 3 ¹¿ ¯ which, using the result in (1.7), gives of Chapter 1 96 L ^ f (t )` e 2 s 3 L > f1 (t )@ (1.19) § 2· f1 ¨ t ¸ sin 3t 2 © 3¹ replace t t 2 3 f1 (t ) sin 3t then its Laplace transform is L ^ f1 (t )` 3 s2 9 Eq. (1.19) becomes 2 s§ 3 · L ^ f (t )` e 3 ¨ 2 ¸. © s 9¹ Example 1.58. Consider the waveform given in Figure 1.19. (a ) Write a mathematical expression for f (t). (b) Find the Laplace transform by expressing it in the Heaviside unit step function. The Laplace Transform 97 f(t) 10 5 0 2 4 t –5 Figure 1.19 Solution: The function is continuous, but is defined differently on the intervals. As such, the mathematical expression for the function is ­5t ° f (t ) ®5 °0 ¯ 0dt d2 2t d4 tt4 In terms of unit step functions, f f (t ) t can be expressed as f1 t ^ f 2 t f1 t ` u t a ^ f3 t f 2 t ` u t b f (t ) 5t 5 t 1 u t 2 5u t 4 Taking the Laplace transform, we have L ^ f (t )` L ^5t` 5L ^ t 1 u t 2 ` 5L ^u t 4 ` Chapter 1 98 We cannot apply the second translation theorem with f t in this form, since, according to the second translation theorem, for the first term we must have a function of t 2 and for the second term a function of t 4 . We can apply the second shifting property to the above result to obtain L ^ f (t )` 5 5e4 s 2 s 5 e L f ( t ) > @ 1 s2 s The function f t is thus rewritten as follows. f1 (t 2) t 1 replace t t2 f1 (t ) t 3 then its Laplace transform is L ^ f1 (t )` 1 3 s2 s Eq. (1.20) becomes L ^ f (t )` 5 3· e 4 s 2 s § 1 5 e 5 . ¨ 2 ¸ s2 s ©s s¹ (1.20) The Laplace Transform 99 Example 1.59. Express in terms of the Heaviside unit step function and find the Laplace transform of f (t ) t 1 t 1 , t t 0. Solution: t 1 t 1 , t t 0. Given f (t ) Clearly ­2 f (t ) ® ¯2t 0 d t d1 t !1 In terms of the unit step function, f f (t ) t can be expressed as f1 t ^ f 2 t f1 t ` u t a f (t ) 2 > 2t 2@ u t 1 Taking the Laplace transform, we have L ^ f (t )` L > 2@ L ^ 2t 2 u t 1 ` which, using the result in (1.7), gives L ^ f (t )` 2 s e L ^ f1 (t )` s The function f t is thus rewritten as follows. (1.21) Chapter 1 100 f1 (t 1) 2t 2 replace t t 1 f1 (t ) 2t then its Laplace transform is L ^ f1 (t )` 2 s2 Eq. (1.21) becomes L ^ f (t )` 2 s § 2 · e ¨ 2 ¸. s ©s ¹ Thus, L ^ f (t )` 2 s e s . 2 s Example 1.60. Consider the waveform shown in Figure 1.20. (a ) Write a mathematical expression for f (t). (b) Find the Laplace transform by expressing it in the Heaviside unit step function. The Laplace Transform 101 f(t) 10 7 0 1 2 3 t Figure 1.20 Solution: The function is continuous, but is defined differently on the intervals. As such, the mathematical expression for the function is ­0 ° °10 t 1 f (t ) ® °7 °0 ¯ 0 d t d1 1 t d 2 2t d3 t !3 In terms of the unit step function, f f (t ) t can be expressed as f1 t ^ f 2 t f1 t ` u t a ^ f3 t f 2 t ` u t b ^ f t f t `u t c 4 3 f (t ) 10 t 1 u t 1 17 10t u t 2 7u t 3 . Taking the Laplace transform, we have Chapter 1 102 L ^10 t 1 u t 1 ` L ^ 17 10t u t 2 ` 7 L ^u t 3 `. L > f (t ) @ We cannot apply the second translation theorem with f t in this form, since, according to the second translation theorem, for the first term we must have a function of t 1 , for the second term a function of t 2 , and for the third term a function of t 3 . We can apply the second shifting property to the above result to obtain 7e3s e L ^ f1 (t )` e L ^ f 2 (t )` s L ^ f (t )` s The function f 2 s t is thus rewritten as follows. f1 (t 1) 10 t 1 t 1 replace t f1 (t ) 10t then its Laplace transform is L > f1 (t )@ 10 s2 Eq. (1.22) becomes f 2 (t 2) replace t 17 10t t2 f 2 (t ) 10t 3 then its Laplace transform is L > f 2 (t )@ 10 3 s2 s (1.22) The Laplace Transform L ^ f (t )` 103 10e s 2 s § 10 3 · 7e 3s . e ¨ 2 ¸ s2 s ©s s¹ Thus, L ^ f (t )` 10 s 1 e e 2 s 3e 2 s 7e 3 s . 2 s s Example 1.61. Transform F s 1 e s 2e 2 s 2 se S s 2 into s2 s2 s s 1 the t-domain. Solution: Application of the second shifting theorem gives f t L1 ^F s ` f t t t 2 u t 2 2u t 2 2cos t S u t S f t t t u t 2 2 cos t S u t S . Thus, the time domain function is ­t ° f (t ) ®0 °2 cos t ¯ 0dt d2 2t dS . t !S Example 1.62. Determine the Laplace transform of the Bessel functions a f (t ) J0 t b f (t ) J1 t . Solution: Chapter 1 104 a We know that J0 t t2 t4 t6 1 2 2 2 2 2 2 ........ 2 2 4 2 4 6 L ^ J 0 t ` L ^1` L ^J 0 t ` 1 1 1 L ^t 2 ` 2 2 L ^t 4 ` 2 2 2 L ^t 6 ` ........ 22 2 4 2 4 6 1 1 2! 1 4! 1 6! 2 3 2 2 5 2 2 2 7 ........ s 2 s 2 4 s 2 4 6 s Clearly L ^J 0 t ` 1 § 1 § 1 · 1 3 § 1 · 1 3 5 § 1 · · 1 ¨ 2 ¸ ¨ 4 ¸ ¨ 6 ¸ ........ ¸ ¨ s © 2 © s ¹ 24 © s ¹ 246 © s ¹ ¹ L ^J 0 t ` 1§ 1· ¨1 2 ¸ s© s ¹ 1 2 . Thus, L ^J 0 t ` 1 1 s2 b We have J 0' t . J1 t . Therefore, by the derivative property, L ^ J1 t ` Thus, L ^ J 0' t ` ^ ª º 1» ¬ 1 s ¼. ` « sL ^ J 0 t ` 1 s 2 The Laplace Transform 105 § s · L ^ J1 t ` ¨ 1 ¸. 1 s2 ¹ © f Example 1.63. Evaluate ³e 2 t 1 cos 3t dt . 0 Solution: Using Table 1.1, L ^ 1 cos 3t ` F s 1 1 . 2 s s 9 By definition of the Laplace transform, f ³e 2 t 1 cos 3t dt L ^1 cos 3t` s 2 1 cos 3t dt 9 . 26 0 1 ½ ­1 ® 2 ¾ ¯s s 9¿ s 2 9 26 Thus, f ³e 2 t 0 Summary In this chapter, we have described and explained the properties of Laplace transforms. x We started with a definition and description of Laplace transforms, including some of their standard functions: the constant function; the exponential function; the sine function; the cosine function; the hyperbolic function; the unit step; the delta function; and the ramp function. Some standard functions of the Laplace transform have Chapter 1 106 been tabulated and several numerical examples have been solved based on the standard functions. x The properties of Laplace transforms have been stated and proved. These include linearity, first shifting, multiplication, and timescaling. Properties, such as time differentiation, time integration, and initial and final value theorem, have also been stated and explained. The Laplace transform has been evaluated in terms of its properties and illustrated using several solved examples. The property of periodicity has been proved and has been shown to be useful for finding the Laplace transform of some standard periodic functions. We have demonstrated the use of the property of periodicity to find the Laplace transform of any periodic function given its waveform. The physical significance of all these properties has been explained. The second shifting property has been proved, which is useful for finding the Laplace transform of discontinuous functions. We have illustrated various waveforms to find the Laplace transform of discontinuous functions using the second shifting property. CHAPTER 2 THE INVERSE LAPLACE TRANSFORM 2.1 Introduction Virtually all operations have their inverses; for example, subtraction is the inverse of addition, division is the inverse of multiplication, and integration is the inverse of differentiation. The Laplace transform is no exception. We can define the inverse of the Laplace transform as follows: If F s represents the Laplace transform of a function f t , that is, L ^ f t ` F s , we then say f t transform of F s and write f t is the inverse Laplace L1 ^ F s ` . In this chapter, we will mainly restrict ourselves to describing different techniques for finding the inverse Laplace transform. In Section 2.2, we derive the relation between Laplace and Fourier transforms. The properties of the inverse Laplace transform, such as linearity, shifting, differentiation, and integration, are treated in sections 2.3 to 2.6. In Section 2.7, we consider the procedure for finding the inverse Laplace transform by the partial fractions method. In Section 2.8, we define the convolution between two functions to find the inverse Laplace transform of the product of two functions in the s domain by applying the convolution theorem. Chapter 2 108 LEARNING OBJECTIVES After studying this chapter, it is expected that you: x Have understood and are able to apply the definition of the inverse Laplace transform. x Can find the inverse Laplace transform of complex functions by using the table to apply the transform’s properties and are able to apply the method of partial fraction expansion. x Can find the inverse Laplace transform using the Bromwich integral formula. x Know and can apply the convolution between two functions and the convolution theorem. x Know and can apply the convolution to solve the integral equation. 2.2 The Inversion Integral for the Laplace Transform When applying the Laplace transform to most practical problems and obtaining the transform F s of the required result, it is usually possible to find the required inverse transform f t by using Table 2.1. This table presents Laplace transform pairs together with the operational properties listed in Table 1.2 (Chapter 1). As tables of transform pairs do not always contain the required inverse Laplace transform and s must be allowed to be complex, some other method must be found by which to determine f t L1 ^ F s ` . The Inverse Laplace Transform The method we derive here shows that transform F f t 109 possesses a Laplace s so that f F s ³e st f t dt f (2.1) where s can be complex and transform F f t can be recovered from its Laplace s by means of the complex line integral V jf f t 1 e st F s ds. ³ 2S V jf (2.2) where c ! 0 is a suitable real constant. The formula in (2.2) is called the inversion integral of the Laplace transform F s . To establish the result in (2.2), we derive the relationship between the Fourier transform and the Laplace transform. 2.2.1 Relationship Between Laplace Transforms and Fourier Transforms When the complex variable s is purely imaginary, i.e. s j: , Eq. (2.1) becomes F j: F^f t ` f ³e j:t f t dt f Eq. (2.3) is the Fourier transform of f (2.3) t Chapter 2 110 F s s j: F^f t `. If s is not purely imaginary, i.e. s V j:, Eq. (2.3) can be written as f F V j: ³e V j: t f t dt f (2.4) f F V j: V ³ e ^e f t ` dt j:t t f (2.5) The right-hand side of Eq. (2.5) is the Fourier transform of e V t f t . Thus, the Laplace transform can be interpreted as the Fourier transform of f t after multiplication by a real exponential signal e From Eq. (2.5), that the Laplace transform f t ^ V t . F V j: of a signal is given by f F e V t f t ` ³ e ^e j:t V t f t ` dt. f Applying the inverse Fourier transform to the above relationship, we obtain e V t f t ^ f ` F 1 ¬ª F eV t f t ¼º F 1 ¬ª F V j: ¼º 1 j:t ³ e F V j: d : 2S f (2.6) Multiplying both sides of Eq. (2.6) by e V t it follows that The Inverse Laplace Transform 111 f f t As s 1 e V j: t F V j: d : ³ 2S f V j: and V is a constant, ds (2.7) jd : . Substituting these values in Eq. (2.7) and changing the variable of integration from s to :, we arrive at the following inverse Laplace transform V jf f t 1 e st F s ds. ³ 2S j V jf (2.8) Equation (2.8), our inverse transformation, is usually known as the Bromwich integral, although it is also referred to the Fourier–Mellin theorem or the Fourier Mellin integral. This integral is evaluated by applying the standard methods of contour integration. If t ! 0, the contour may be closed by an infinite semicircle in the left half-plane. Then, by the residual theorem, V jf f t 1 e st F s ds ³ 2S j V jf ¦ sum of residues . In the next section, we will examine a direct method for finding inverse Laplace transforms based on the theory of functions of a complex variable. In the meantime, we shall be content with using tables, which is the simplest method for most of the applications. However, to use the tables, we require a mathematical technique to resolve transforms into the listed forms. Chapter 2 112 2.2.2 Inversion Using the Bromwich Integral Formula ª º a » using the Bromwich L1 « 2 «¬ s a 2 »¼ Example 2.1. Determine integral formula. Solution: Let F a s a2 s a 2 sa sa , then ae st , sa sa e st F s The poles F s are s Re s ^ a ` lim e st F s s a s oa Re s ^ a ` a &s ^ ^ a . These are both simple poles. lim e st F s s a s o a ­ st ½ at ` lim ® sae a ¾ e2 s oa ` ¯ ¿ ­ e st a ½ lim ® ¾ s o a s a ¯ ¿ e at . 2 Using the Bromwich integral V jf f t 1 e st F s ds ³ 2S j V jf ¦ sum of residues 1 at at e e 2 sinh at. To further progress with the inverse Laplace transform, it is necessary to have a table of inverse Laplace transform pairs for the most commonly The Inverse Laplace Transform 113 occurring functions. Table 2.1 provides a list of the most useful inverse Laplace transform pairs involving elementary functions. Table 2.1 Inverse Laplace Transform Pairs F ( s) L^ f (t )` Transform L ^1` f (t ) L1 ^F ( s)` Inverse Transform 1 s ­1 ½ 1 L1 ® ¾ ¯s¿ L tn ^ ` n! s n 1 t n 1 ­ 1 ½ L1 ® n ¾ n 1 ! ¯ s ¿ ^ ` 1 sa eat L e at ­ 1 ½ L1 ® ¾ ¯s a¿ L ^sinh at` 2 a s a2 ­ a ½ sinh at L1 ® 2 2 ¾ ¯s a ¿ L ^cosh at` 2 s s a2 cosh at ­ s ½ L1 ® 2 2 ¾ ¯s a ¿ L ^sin at` 2 a s a2 sin at ­ a ½ L1 ® 2 2 ¾ ¯s a ¿ L ^cos at` s s a2 cos at ­ s ½ L1 ® 2 2 ¾ ¯s a ¿ 2 Chapter 2 114 L ^u t ` 1 s u t e as s L ^u t a ` ­1 ½ L1 ® ¾ ¯s¿ ­ e as ½ L1 ® ¾ ¯ s ¿ u t a L ^G t ` 1 G t L ^G t a ` e as G t a ^ L e at t n n! ` sa L eat cos bt ^ ` ^ ` L e at sin bt L1 ^1` ^ ` L1 e as ­° 1 ½° at t n 1 L1 ® e n ¾ n 1 ! °¯ s a °¿ n 1 sa 2 s a b2 b 2 sa b 2 ­° ½° at sa L1 ® ¾ e cos bt 2 2 °¯ s a b °¿ ­° ½° at b L1 ® ¾ e sin bt 2 2 °¯ s a b °¿ 2.3 The Inverse Laplace Transform is a Linear Transform The linearity property for the Laplace transform (Property 1.5.1) states that if C1 and C2 are any constants, then L ^C1 f t C2 g t ` C1 L ^ f t ` C2 L ^ g t ` C1 F s C2G s . It follows from the above definition that The Inverse Laplace Transform L1 ^C1 F s C2G s ` C1 f t C2 g t 115 C1 L1 ^F s ` C2 L1 ^G s ` L1 is also a linear operator. For example, if we consider an arbitrary function of s , there is no guarantee that we find a function of t , i.e. an inverse Laplace transform of t . One important condition is that the function of s must tend to zero as s o f. When we are sure that a function of s has arisen so that the inverse Laplace transform operator from a Laplace transform, we can use certain techniques and theorems to help us invert it. Partial fractions simplify rational functions and can help identify standard forms, for example, the exponential, hyperbolic, and trigonometric functions. The second shift of the differentiation and integration theorems that we have come across previously further extend the repertoire of standard forms. 1 Example 2.2. Determine (i ) L ª 2s 9 º ª Ds E º « 2 » (ii ) L1 « 2 ». «¬ s 9 »¼ «¬ s O 2 »¼ Solution: (i ) We first rewrite the given function of s as two expressions by means of term by term division and get ª 2s 9 º » L1 « 2 «¬ s 9 »¼ ª 2s 9 º » 2 L1 « 2 s 9 »¼ «¬ s 9 ª s º ª 3 º » 3L1 « 2 ». 2 L1 « 2 «¬ s 9 »¼ «¬ s 9 »¼ Applying the inverse Laplace transform to the above equation, and using its linearity, we get the following result Chapter 2 116 ª 2s 9 º » 2 cos 3t 3sin 3t. L1 « 2 «¬ s 9 »¼ (ii ) ª Ds E º ª Ds ª s º E ª O º E º L1 « 2 2 » L1 « 2 2 2 2 » D L1 « 2 2 » L1 « 2 2 » s O »¼ «¬ s O »¼ «¬ s O «¬ s O »¼ O «¬ s O »¼ Applying the inverse Laplace transform to the above equation, and using its linearity, we get the following result ª Ds E º E » D O L1 « 2 cos t sin Ot. O «¬ s O 2 »¼ 2.4 Inversion Using the First Shift Theorem Property 1.5.3 shows saw that, if F s is the Laplace transform of f t , then, for a scalar a, ^F s a ` is the Laplace transform of e f t . Expressed in the at inverse form, the theorem becomes L1 ^ F s a ` e at f t . ª º 3 « ». Example 2.3. Determine L « s2 2 9 » ¬« ¼» 1 The Inverse Laplace Transform 117 Solution: 3 2 s2 9 since 3 s2 9 ª 3 º « 2 » «¬ s 9 »¼ sos 2 L ^sin 3t` , the shift theorem gives ­ ½ 3 ° ° L ® ¾ 2 ° s3 9 ° ¯ ¿ e 2t sin 3t. Example 2.4. Determine ª º s2 ». L1 « 2 «¬ s 2 s 5 »¼ 1 Solution: Observe that s2 s 2s 5 2 s 1 2 s 1 4 since s s 4 2 s 1 3 s 1 2 2 s 1 4 s 1 4 ª s º « 2 » and «¬ s 4 »¼ s o s 1 L ^cos 2t` and 1 2 s 1 4 1 s 4 2 3 2 s 1 4 ª 1 º « 2 » «¬ s 4 »¼ s o s 1 1 L ^cos 2t` . 2 Chapter 2 118 Applying the inverse Laplace transform to the above equation, and using its linearity, we get the following result ª º s2 » L1 « 2 «¬ s 2 s 5 »¼ ­ ½ ­ ½ s 1 3 ° ° 1 ° ° L1 ® L ¾ ® ¾ 2 2 ° s 1 4 ° ° s 1 4 ° ¯ ¿ ¯ ¿ ª s 2 º t 3 » e cos 2t e t sin 2t. L1 « 2 2 «¬ s 2s 5 »¼ Example 2.5. Determine ª º 5s 2 » L1 « 2 «¬ s 6 s 13 »¼ Solution: First, we complete the square to get 2 s 2 6 s 13 s3 4 . Observe that 5s 2 s 6 s 13 5 s 3 13 2 2 s3 5 s3 4 2 s3 4 13 1 2 s3 4 Applying the inverse Laplace transform to the above equation, and using its linearity, we now use the L1 ^ F s a ` e at f t , to conclude frequency shift theorem The Inverse Laplace Transform 119 ª 5s 2 º 13 » 5e 3t cos 2t e 3t sin 2t. L1 « 2 2 «¬ s 6s 13 »¼ 2.5 Inverse Transform by Differentiation and Integration Given the function F s , its inverse Laplace transform f t may be formed by evaluating the inverse transform g t that F sG s and f t s dg t dt of G s F s s , so . Similarly, given the function F s , its inverse transform may be found by evaluating the inverse g t of G s sF s , so that F s G s s t f t ³ g t dt. 0 Example 2.6. Evaluate f t given that F s 2a 2 . s s 2 4a 2 Solution: Let G s sF s 2a 2 s 2 4a 2 a 2a 2 s 2a Taking the inverse Laplace transform, we get 2 . and Chapter 2 120 g t a sinh 2at then, t f t t ³ g t dt ³ a sinh 2at dt 0 a cosh 2at 2a 0 t 1 cosh 2at 1 2 t 0 Thus, f t 1 cosh 2at 1 . 2 Example 2.7. Evaluate f t given that F s § sa· log e ¨ ¸. © s b ¹ Solution: Let F log e s a log e s b s F' s 1 1 sa sa F ' s 1 1 . sa sa Applying the inverse Laplace transform to the above equation, and using its linearity, gives us the following result. ^ L1 F ' s ­ ½ °¯ °¿ ­ ½ °¯ °¿ ` L °® s 1 a °¾ L °® s 1 a °¾ 1 1 The Inverse Laplace Transform ^ L1 F ' s 121 ` e e . at bt ^ t ` We have seen that L t f dF s ds F ' s then, tf t e at ebt . Thus, f t eat ebt . t Example 2.8. Evaluate f t given that F s Solution: §1· tan 1 ¨ ¸ ©s¹ Let F s F' s 1 s 1 F' s 1 . s 1 2 2 Taking the inverse Laplace transform, we get ^ L1 F ' s ` L ­®¯ s 1 1½¾¿ 1 2 §1· tan 1 ¨ ¸ . ©s¹ Chapter 2 122 ^ ` sin t . L1 F ' s ^ We have seen that L t f t ` dF s ds F ' s then, tf t sin t Thus, sin t . t f t Example 2.9. Evaluate f t given that F s § s2 a2 · log e ¨ ¸. 2 © s ¹ Solution: Let F log e s 2 a 2 log e s 2 s F' s 2s 2 2 s s a F ' s 2 2s 2 s s a 2 2 Applying the inverse Laplace transform to the above equation, and using its linearity, we get the following result The Inverse Laplace Transform ­° s ½° ­1 ½ 2 L1 ® 2 2 ¾ 2 L1 ® ¾ ¯s¿ °¯ s a °¿ ^ ` ^ ` 2 cos at 2 . L1 F ' s L1 F ' s 123 ^ We have seen that L t f t ` dF s ds F ' s then, 2 1 cos at t f t . Thus, 2 1 cos at f t t . Example 2.10. Evaluate f t given that F s Solution: Let F log e s 2 E 2 log e s 2 s F' s 2s 2 2 s E s F ' s 2s 2 2 . 2 s E s 2 § s2 E 2 · log e ¨ ¸. 2 © s ¹ Chapter 2 124 Taking the inverse Laplace transform, we get ^ ` L ­® s 2sE ½¾ L ­®¯ 2s ¾½¿ ^ ` 2 cos E t 2 . L1 F ' s L1 F ' s 1 1 ¯ ^ We have seen that L t f 2 2 ¿ t ` dF s F ' s ds then, tf t 2 cos E t 2 . Thus, f t 2 1 cos E t t 1 Example 2.11. Determine L ª 1 º « ». ¬ s s 1 ¼ Solution: We have ­1 ½ L® ¾ ¯ t¿ 1 2 ­ ½ L ®t ¾ ¯ ¿ Its inversion is §1· *¨ ¸ ©2¹ s1 2 S S 12 s s . The Inverse Laplace Transform ­ 1 ½ L1 ® ¾ ¯ s¿ 125 1 . St As such, the shift theorem gives et ­ 1 ½ L1 ® ¾ ¯ s 1 ¿ . St To complete the inversion process, we now make use of the Laplace transform of an integral ­F s ½ L ® ¾ ¯ s ¿ 1 t ³ f W dW . 0 1 Using this result with L ª 1 º L « » ¬ s s 1 ¼ 1 1 t ­ 1 ½ ® ¾ gives ¯ s 1 ¿ e W S ³0 SW x 2 converts this to The change of variable W t ª 1 º L « » ¬ s s 1 ¼ 2 2 e x dx, ³ S 0 1 however, the error function erf erf x 2 dW . x e S ³ 0 W 2 dW x is given by Chapter 2 126 1 so L ª 1 º « » ¬ s s 1 ¼ erf t . 2.6 Inversion Using the Second Shift Theorem This theorem plays a vital role in determining inverse transforms. As indicated earlier, shifting is inherent in most practical systems and engineers are interested in knowing how they respond. In theorem 1.7, we saw that if F s is the Laplace transform of f t , then, for a scalar a, ^e F s ` is the Laplace transform of f t a u t a . Expressed as in the inverse form, the theorem becomes ^ L1 e as F s ` f t a u t a . ª s 1 · º» ¸ 2 ¨ s2 4 ¸» s 1 © ¹¼ § 1 S s Example 2.12. Determine a L « e ¨ « ¬ ª º 1 ». b L1 « «¬ s 1 e s »¼ Solution: a This may be written as L1 ª¬e S s F s º¼ , where F s s 1 2 . s 4 s 1 2 First, we obtain the inverse transform f t of F s The Inverse Laplace Transform 127 cos t sin t f t Then, using the theorem, we have ª § s 1 · º» 1 S s ¸ L ª¬e F s º¼ L1 «eS s ¨ 2 2 ¸» « ¨ s 4 s 1 ¹¼ ¬ © b Let F s Here, ^cos t S sin t S ` u t S . 1 . s 1 e s 1 can be interpreted as the sum of a geometric series with 1 e s the common ratio e 1 1 e s s , so that we may write 1 e s e 2 s e 3 s e 4 s ........ F s 1 ª¬1 e s e2 s e3s e4 s ........º¼ s F s 1 e s e2 s e3s e4 s ...... s s s s s Applying the inverse Laplace transform to the above equation, and using its linearity, we get the following result f t 1 u t 1 u t 2 u t 3 u t 4 ...... Thus, the function can be written as follows (its graph is shown in Figure 2.1 Chapter 2 128 f(t) f t ­1 0 t d 1 °2 1 t d 2 3 ° °3 2 t d 3 ® 2 °4 3 t d 4 °..................... 1 ° ¯....................... 0 1 2 3 Figure 2.1 2.7 The Inverse Laplace Transform Using Partial Fractions Integral calculus shows us how to integrate rational functions by using partial fraction decomposition. In order to efficiently derive inverse Laplace transforms of rational functions using a table of Laplace transforms, we must be conversant with a variety of partial fraction decompositions. Partial fractions play an important role in deriving inverse Laplace transforms. Partial fractions provide a method for the decomposition of a rational expression into a sum of simple rational functions. In this section, we will review some of the basic algebra for the The Inverse Laplace Transform important cases in which the denominator of a Laplace transform F 129 s contains distinct linear factors, repeated linear factors, and quadratic polynomials. In many cases, F s is the quotient of two polynomials with real coefficients. If the numerator polynomial is of the same or higher degree than the denominator polynomial, then we divide the numerator polynomial by the denominator polynomial. We continue the division until the numerator polynomial of the remainder is one degree less than the denominator. This results in a polynomial in s and a proper fraction. The resulting proper fraction can be expanded into a partial fraction. The procedure for finding a Laplace transform, given the function in the frequency domain, can be stated as follows: Step 1: Factorize the denominator to get the roots of the function. Step 2: Use partial fraction expansion. Step 3: Find the inverse Laplace transform of each term. The following examples illustrate partial fraction decomposition when the denominator of F s is factorable into: (i) distinct linear factors; (ii) repeated linear factors; and (iii) quadratic polynomials. 2.7.1 Partial Fractions: Distinct Linear Factors If D s can be factored into a product of distinct linear factors, then D s s s1 s s2 s s3 ......... s si , Chapter 2 130 , where si represents a distinct real number. As such, the partial fraction expansion has the form N s A3 Ai A1 A2 , ......... s s1 s s2 s s3 s si D s where Ai , represents a real number. There are various ways of determining the constants A1 , A2 , A3 ,...... Ai . In the next example, we demonstrate three such methods. 1 Example 2.13. Determine L where F s ª¬ F s º¼ , 2 s 2 9 s 11 . s 2 s 3 s 1 Solution: Method 1: Cover-up Method. The denominator is already in the factored form completing step 1. In step 2, we use partial fraction expansion and decompose the function into three terms. We begin by finding the partial fraction expansion for F s . The denominator consists of three distinct linear factors. The expansion has the form 2 s 2 9 s 11 s 2 s 3 s 1 A B C s2 s3 s 1 The Inverse Laplace Transform 131 where A, B, and C are real numbers to be determined. A B C ª 2 s 2 9 s 11 s 2 º « » 1 , «¬ s 2 s 3 s 1 »¼ s 2 2 ª 2 s 9 s 11 s 3 º « » 2, «¬ s 2 s 3 s 1 »¼ s 3 ª 2 s 2 9 s 11 º « » ¬« s 2 s 3 ¼» s 1 Hence, the given function F 2 s 2 9 s 11 s 2 s 3 s 1 3 . s can be expanded as 1 2 3 s2 s3 s 1 In step 3, we find the inverse Laplace transform of each term. Now that we have obtained the partial fraction expansion, taking the inverse Laplace transform of each term on the right and using the linearity property of the Laplace transform, we find that ­° 2 s 2 9s 11 ½° 1 ­° 1 ½° ­ 1 ½° ­ 1 ½° 1 ° 1 ° L1 ® ¾ L ® ¾ 2L ® ¾ 3L ® ¾ °¯ s 2 s 3 s 1 °¿ °¯ s 2 °¿ °¯ s 3 °¿ °¯ s 1 °¿ Finally, using the transform pairs established in Table 2.1, we have ª 2s 2 9s 11 º 2t 3t t L « » e 2e 3e . ¬« s 2 s 3 s 1 ¼» 1 Chapter 2 132 Method 2: Classical Method. The denominator is already in the factored form, completing step 1. In step 2, we use partial fraction expansion and decompose the function into three terms. We begin by finding the partial fraction expansion for F s . The denominator consists of three distinct linear factors and so the expansion has the form 2 s 2 9 s 11 s 2 s 3 s 1 A B C s2 s3 s 1 where A, B, and C are real numbers to be determined. In this procedure, which works for all partial fraction expansions, we first multiply the expansion equation by the given rational function’s denominator. This leaves us with two identical polynomials. Equating the coefficients of s k leads to a system of linear equations, which we can solve to determine the unknown constants. In this example, we multiply the above equation by s 2 s 3 s 1 and find 2s 2 9s 11 A s 3 s 1 B s 2 s 1 C s 2 s 3 . Equating the coefficients of s2, s , and 1 gives the following system of linear equations A B C 2 , 4A B C 9 , The Inverse Laplace Transform 3 A 2 B 6C 133 11 , solving this system yields A 1 , B Hence, the given function F s can be expanded as 2 s 2 9 s 11 s 2 s 3 s 1 2, and C 3. 1 2 3 s2 s3 s 1 In step 3, we find the inverse Laplace transform of each term. Now that we have obtained the partial fraction expansion, taking the inverse Laplace transform of each term on the right and using the linearity property of the Laplace transform, we find that ­° 2 s 2 9 s 11 ½° 1 ­° 1 ½° ­ 1 ½° ­ 1 ½° 1 ° 1 ° L1 ® ¾ L ® ¾ 2L ® ¾ 3L ® ¾ °¯ s 2 s 3 s 1 °¿ °¯ s 2 °¿ °¯ s 3 °¿ °¯ s 1 °¿ Finally, using the transform pairs established in Table 2.1, we have ª 2s 2 9s 11 º 2t 3t t L1 « » e 2e 3e . «¬ s 2 s 3 s 1 »¼ Method 3: Alternative Method. The denominator is already in the factored form, completing step 1. In step 2, we will use partial fraction expansion and decompose the function into three terms. Although the method of comparing coefficients is direct, it can also be laborious. A more efficient alternative, especially for fractions having Chapter 2 134 distinct linear factors in the denominator, is based on the fact that if two polynomials of degree k are equal for more than k replacements of the variable, they are identical for all values of the variable. We begin by finding the partial fraction expansion for F s . The denominator consists of three distinct linear factors and so the expansion has the form 2 s 2 9 s 11 s 2 s 3 s 1 A B C s2 s3 s 1 where A, B, and C are real numbers to be determined. We have 2s 2 9s 11 A s 3 s 1 B s 2 s 1 C s 2 s 3 In this method for finding the constants A, B, and C from the above equation, we choose three values for s and substitute them into the above equation to obtain three linear equations in the three unknowns. If we are careful in our choice of values for s, the system is easy to solve. In this case, the above equation is simplified if s gives 15 A 15 A Next, using s 10 B 1 . 3 gives 20 B 2. 2, 3 or -1. Using s 2 The Inverse Laplace Transform Finally, using s 6C 18 C 135 1 gives 3 . As such, the given function F s can be expanded as 2 s 2 9 s 11 s 2 s 3 s 1 1 2 3 . s2 s3 s 1 In step 3, we find the inverse Laplace transform of each term. Now that we have obtained the partial fraction expansion, taking the inverse Laplace transform of each term on the right and using the linearity property of the Laplace transform, we find that 2 ­ 1 °½ ­ 1 °½ °­ 2s 9s 11 °½ 1 °­ 1 °½ 1 ° 1 ° L1 ® ¾ L ® ¾ 2L ® ¾ 3L ® ¾ °¯ s 2 ¿° ¯° s 2 s 3 s 1 ¿° ¯° s 3 ¿° ¯° s 1 ¿° Finally, using the transform pairs established in Table 2.1, we have ª 2s2 9s 11 º 3t t 2t L « » e 2e 3e . «¬ s 2 s 3 s 1 »¼ 1 Chapter 2 136 1 Example 2.14. Determine L where F s ª¬ F s º¼ , s2 1 . s s 1 s 1 s 2 Solution: Method 1: Cover-up Method. The denominator is already in the factored form, completing step 1. In step 2, we use partial fraction expansion and decompose the function in four terms. We begin by finding the partial fraction expansion for F s . The denominator consists of four distinct linear factors and so the expansion has the form s2 1 s s 1 s 1 s 2 A B C D s s 1 s 1 s2 where A, B, C, and D are real numbers to be determined. ª º s2 1 A « » ¬« s 1 s 1 s 2 ¼» s 0 1 , 2 ª º s2 1 B « 1, C » ¬« s s 1 s 2 ¼» s 1 D ª º s2 1 « » ¬« s 1 s s 1 ¼» s 2 5 . 6 ª º s2 1 1 , « » 3 ¬« s 1 s s 2 ¼» s 1 The Inverse Laplace Transform 137 Hence, the given function F s can be expanded as s2 1 s s 1 s 1 s 2 11 1 1 1 5 1 2s s 1 3 s 1 6 s 2 In step 3, we find the inverse Laplace transform of each term. Now that we have obtained the partial fraction expansion, taking the inverse Laplace transform of each term on the right and using the linearity property of the Laplace transform, we find that ­° ½° 1 1 ­1½ 1 ­° 1 ½° 1 1 ­° 1 ½° 5 1 ­° 1 ½° s2 1 L1 ® ¾ L ® ¾ L ® ¾ L ® ¾ L ® ¾ ¯°s s 1 s 1 s 2 ¿° 2 ¯s ¿ ¯° s 1 ¿° 3 ¯° s 1 ¿° 6 ¯° s 2 ¿° . Finally, using the transform pairs established in Table 2.1, we have ­° ½° 1 t 1 t 5 2t s2 1 L1 ® e e e . ¾ 3 6 °¯ s s 1 s 1 s 2 °¿ 2 Method 2: Classical Method. The denominator is already in the factored form, completing step 1. In step 2, we use partial fraction expansion and decompose the function into three terms. We begin by finding the partial fraction expansion for F s . The denominator consists of three distinct linear factors and so the expansion has the form Chapter 2 138 s2 1 s s 1 s 1 s 2 A B C D s s 1 s 1 s2 where A, B, C, and D are real numbers to be determined. In this procedure, which works for all partial fractions, we first multiply the expansion equation by the given rational function’s denominator. This leaves us with two identical polynomials. Equating the coefficients of s k leads to a system of linear equations that we can solve to determine the unknown constants. In this example, we multiply the above equation by s s 1 s 1 s 2 and find s2 1 A s 1 s 1 s 2 Bs s 1 s 2 Cs s 1 s 2 Ds s 1 s 1 . Equating the coefficients of s3, s2, s, and 1 gives the following system of linear equations A BC D 0 , 2 A B 3C 1 , A 2 B 2C D 2A 0, 1 , solving this system yields A 1 , B 2 1, C Hence, the given function F s can be expanded as 1 , and D 3 5 . 6 The Inverse Laplace Transform s2 1 s s 1 s 1 s 2 139 11 1 1 1 5 1 . 2s s 1 3 s 1 6 s 2 In step 3, we find the inverse Laplace transform of each term. Now that we have obtained the partial fraction expansion, taking the inverse Laplace transform of each term on the right and using the linearity property of the Laplace transform, we find that s2 1 °­ °½ 1 1 ­1½ 1 °­ 1 °½ 1 1 °­ 1 °½ 5 1 °­ 1 °½ L1 ® ¾ L ® ¾ L ® ¾ L ® ¾ L ® ¾ ¯°s s 1 s 1 s 2 ¿° 2 ¯s ¿ ¯° s 1 ¿° 3 ¯° s 1 ¿° 6 ¯° s 2 ¿° . Finally, using the transform pairs established in Table 2.1, we have ­° ½° 1 t 1 t 5 2t s2 1 L ® e e e . ¾ 3 6 °¯ s s 1 s 1 s 2 °¿ 2 1 Method 3: Alternative Method. The denominator is already in the factored form, completing step 1. In step 2, we use partial fraction expansion and decompose the function into three terms. Although the method of comparing coefficients is direct, it can also be laborious. A more efficient alternative, especially for fractions having distinct linear factors in the denominator, is based on the fact that if two polynomials of degree k are equal for more than k replacements for the variable, they are similar for all values of the variable. Chapter 2 140 We begin by finding the partial fraction expansion for F s . The denominator consists of three distinct linear factors and so the expansion has the form s2 1 s s 1 s 1 s 2 A B C D s s 1 s 1 s2 where A, B, C, and D are real numbers to be determined. We have s 2 1 A s 1 s 1 s 2 Bs s 1 s 2 Cs s 1 s 2 Ds s 1 s 1 . To find the constants A, B, C, and D from the above equation, we choose three values for s and substitute them into the above equation to obtain three linear equations for the three unknowns. If we are careful in our choice of values for s, the system is easy to solve. In this case, the above equation is clearly simplified if s Using s 0 gives 2A 1 A 1 2 Next, using s 1 gives 2 B 2 B Next, using s 6C 1 1 gives 2 C 1 3 0,1, 1 , or 2. The Inverse Laplace Transform Finally, using s 6D 5 D 141 2 gives 5 . 6 Hence, the given function F s2 1 s s 1 s 1 s 2 s can be expanded as 11 1 1 1 5 1 . 2 s s 1 3 s 1 6 s 2 In step 3, we find the inverse Laplace transform of each term. Now that we have obtained the partial fraction expansion, taking the inverse Laplace transform of each term on the right and using the linearity property of the Laplace transform, we find that s2 1 °­ °½ 1 1 ­ 1 ½ 1 °­ 1 °½ 1 1 °­ 1 °½ 5 1 °­ 1 °½ L1 ® ¾ L ® ¾ L ® ¾ L ® ¾ L ® ¾ ¯° s s 1 s 1 s 2 ¿° 2 ¯ s ¿ ¯° s 1 ¿° 3 ¯° s 1 ¿° 6 ¯° s 2 ¿° . Finally, using the transform pairs established in Table 2.1, we have ­° ½° 1 t 1 t 5 2t s2 1 L ® e e e . ¾ 3 6 °¯ s s 1 s 1 s 2 °¿ 2 1 Chapter 2 142 Example 2.15. Find the inverse Laplace transform of a F s s 2 6s 5 s 2 3s 2 b F s s 3 5s 2 9 s 7 . s 2 3s 2 Solution: All these problems are tackled in a similar fashion by decomposing the expression into partial fractions then identifying the simplified expressions with various standard forms. (a) Step 1. The denominator is in the factored form. Note that the degree of the numerator is the same as the degree of the denominator. So, we have to bring it in the fraction form to apply partial fraction expansion. In many cases, F s is the quotient of two polynomials with real coefficients. If the numerator polynomial is of the same or higher degree than the denominator polynomial, we divide the numerator polynomial by the denominator polynomial. The division is carried forward until the numerator polynomial of the remainder is one degree less than the denominator. This results in a polynomial in s plus a proper fraction. The proper fraction can be expanded into a partial fraction. s 2 6s 5 3s 5 . 1 2 s 3s 2 s 1 s 2 In step 2, we use partial fraction expansion and decompose the function into three terms. The proper fraction is expanded into partial fraction form The Inverse Laplace Transform 143 s 2 6s 5 A B 1 2 s 3s 2 s 1 s2 where A and B are real numbers to be determined. ª 3s 5 º A « » ¬« s 2 ¼» s 1 2 , Hence, the given function F s 2 6s 5 s 2 3s 2 1 B ª 3s 5 º 1. « » ¬« s 1 ¼» s 2 s can be expanded as 2 1 s 1 s2 In step 3, we find the inverse Laplace transform of each term. Taking the inverse Laplace transform of each term on the right, and using the linearity property of the Laplace transform, we find that ­ s 2 6s 5 ½ L1 ® 2 ¾ ¯ s 3s 2 ¿ °­ 1 °½ 1 °­ 1 °½ L1 ^1` 2 L1 ® ¾ L ® ¾. °¯ s 1 °¿ °¯ s 2 °¿ Finally, using the transform pairs established in Table 2.1, we have f t G t 2et e2t . (b) Here, since the degree of the numerator polynomial is higher than that of the denominator polynomial, we must divide the numerator by the denominator F s s 3 5s 2 9 s 7 s 2 3s 2 s2 s3 . s 1 s 2 Chapter 2 144 We use partial fraction expansion of the second term of the right-hand side. The proper fraction is expanded into partial fraction form F1 s s3 s 1 s 2 A B s 1 s2 where A and B are real numbers to be determined. ª s 3 º A « » «¬ s 2 »¼ s 1 ª s 3 º B « » «¬ s 1 »¼ s 2 2 , 1 . Hence, the given function F s can be expanded as F s s 3 5s 2 9 s 7 s 2 3s 2 s2 2 1 s 1 s2 Note that the Laplace transform of the unit-impulse function G t is a unity and the Laplace transform of dG t dt ­d f t ½ i.e L ­® d G t ½¾ s. L ® ¾ sF s . ¯ dt ¿ ¯ dt ¿ Thus, f t dG t dt 2G t 2et e2t . Example 2.16. Find the Inverse LT of F s s2 s 1 . s 2 2s 1 The Inverse Laplace Transform 145 Solution: Note that the degree of the numerator is the same as the degree of the denominator. We have to put it in the form of a fraction and divide the numerator polynomial by the denominator polynomial using simple long division. This allows us to apply partial fraction expansion. s2 s 1 3s 1 s2 2s 1 s2 2s 1 ª s 1 1º 3 3 s2 s 1 . 1 3 « » 1 2 2 2 s 2s 1 s 1 s 1 «¬ s 1 »¼ Taking the inverse Laplace transform of each term on the right, and using the linearity property of the Laplace transform, we find that ­ s2 s 1 ½ L1 ® 2 ¾ ¯ s 2s 1¿ ­ 1 °½ ­° 1 ½° 1 ° . L1 ^1` 3L1 ® ¾ 3L ® 2¾ °¯ s 1 °¿ ¯° s 1 ¿° Finally, using the transform pairs established in Table 2.1, we have f t G t 3et 3tet . 1 Example 2.17. Determine L ª¬ F s º¼ , where F s ª º 3s 2 7 « 4 ». 3 2 ¬ s 2s s 2s ¼ Solution: In step 1, we have the denominator in the factored form Chapter 2 146 F s 3s 2 7 . s s 1 s 2 s 1 In step 2, we use partial fraction expansion and decompose the function into three terms. We begin by finding the partial fraction expansion for F s . The denominator consists of four distinct linear factors and so the expansion has the form F s 3s 2 7 s s 1 s 2 s 1 A B C D s s 1 s2 s 1 where A, B, and C are the real numbers to be determined. ª º 3s2 7 7 A « , » «¬ s 1 s 2 s 1 »¼ s 0 2 ª º 3s 2 7 5, B « » ¬« s s 2 s 1 ¼» s 1 C ª 3s 2 7 º « » «¬ s s 1 s 1 »¼ s 2 19 ,D 6 ª º 3s 2 7 « » «¬ s s 1 s 2 »¼ s 1 Hence, the given function F s can be expanded as F s 7 § 1 · § 1 · 19 § 1 · 5 § 1 · ¸ ¨ ¸ ¨ ¸ ¨ ¸ 5¨ 2 © s ¹ ¨© s 1 ¸¹ 6 ¨© s 2 ¸¹ 3 ¨© s 1 ¸¹ In step 3, we find the inverse Laplace transform of each term. . 5 3 . The Inverse Laplace Transform 147 Now that we have obtained the partial fraction expansion, taking the inverse Laplace transform of each term on the right and using the linearity property of the Laplace transform, we find that ­° 1 ½° 19 1 ­° 1 ½° 5 1 ­° 1 ½° 7 1 ­ 1 ½ L ® ¾ 5L1 ® ¾ L ® ¾ L ® ¾ 2 ¯s¿ °¯ s 1 °¿ 6 °¯ s 2 °¿ 3 °¯ s 1 °¿ f t . Finally, using the transform pairs established in Table 2.1, we have 7 19 5 5et e 2t e t . 2 6 3 f t ª º s2 6s 9 Example 2.18. Determine (a) L « » «¬ s 1 s 2 s 4 »¼ 1 1 (b) L ª º s « ». ¬« s 1 s 2 s 3 ¼» Solution: (a) We begin by finding the partial fraction expansion for F s . The denominator of F s , which is D s s 1 s 2 s 4 , has three linear factors of multiplicity 1. As such, the partial fraction expansion for F s has the form s 2 6s 9 s 1 s 2 s 4 A B C s 1 s 2 s4 Chapter 2 148 where A, B, and C are real numbers to be determined. ª s 2 6s 9 º A « » ¬« s 2 s 4 ¼» s 1 C 16 , 5 ª s 2 6s 9 º « » «¬ s 1 s 2 »¼ s 4 Hence, the given function F s s 2 6s 9 s 1 s 2 s 4 B ª s 2 6s 9 º « » ¬« s 1 s 4 ¼» s 2 25 , 6 1 30 can be expanded as 16 ­ 1 ½ 25 ­° 1 ½° 1 ­° 1 ½° ® ¾ ® ¾ ® ¾ 5 ¯ s 1¿ 6 ¯° s 2 ¿° 30 ¯° s 4 ¿° . Taking the inverse Laplace transform of each term on the right and using the linearity property of the Laplace transform, we find that ª º s 2 6s 9 L1 « » «¬ s 1 s 2 s 4 »¼ 16 t 25 2t 1 4t e e e 5 6 30 (b) We begin by finding the partial fraction expansion for F s . The denominator of F s , which is D s s 1 s 2 s 3 , has three linear factors of multiplicity 1. As such, the partial fraction expansion for F s has the form The Inverse Laplace Transform s s 1 s 2 s 3 149 A B C s 1 s 2 s 3 where A, B, and C are real numbers to be determined. ª º 1 s A « , » «¬ s 2 s 3 »¼ s 1 6 ª º s 3 C « » ¬« s 1 s 2 ¼» s 3 10 ª º s B « » «¬ s 1 s 3 »¼ s 2 2 , 15 Hence, the given function F s can be expanded as s s 1 s 2 s 3 1 ­ 1 ½ 2 ­° 1 ½° 3 ­° 1 ½° ® ¾ ® ¾ ® ¾ 6 ¯ s 1¿ 15 ¯° s 2 ¿° 10 ¯° s 3 ¿° Taking the inverse Laplace transform of each term on the right and using the linearity property of the Laplace transform, we find that ª º s L1 « » ¬« s 1 s 2 s 3 ¼» 1 Example 2.19. Determine L ª º 4s 1 L1 « » «¬ s s 1 s 2 s 7 »¼ 1 t 2 2t 3 3t e e e . 6 15 10 ª º 4s 1 « » «¬ s s 1 s 2 s 7 »¼ . Chapter 2 150 Solution: We begin by finding the partial fraction expansion for denominator of F s , which is D s F s . The s s 1 s 2 s 7 , has three linear factors of multiplicity 1. As such, the partial fraction expansion for F s has the form 4s 1 A B C D s s 1 s2 s7 s s 1 s 2 s 7 where A, B, C, and D are real numbers to be determined. C ª º 4s 1 « » ¬« s s 1 s 7 ¼» s 2 3 , 10 D ª º 4s 1 « » ¬« s s 1 s 2 ¼» s 7 29 280 . Hence, the given function F s can be expanded as 4s 1 s s 1 s 2 s 7 § 1 ·1 §1· 1 §3· 1 § 29 · 1 ¨ ¸ ¨ ¨ ¸ ¨ ¸ ¸ © 14 ¹ s © 8 ¹ s 1 © 10 ¹ s 2 © 280 ¹ s 7 . Taking the inverse Laplace transform of each term on the right and using the linearity property of the Laplace transform, we find that 4s1 °­ °½ § 1 · 1 ­1½ §1· 1 °­ 1 °½ § 3 · 1 °­ 1 °½ § 29 · 1 °­ 1 °½ L1 ® ¾ ¾ ¨ ¸L ® ¾¨ ¸L ® ¾¨ ¸L ® ¾¨ ¸L ® ¯°s s1 s2 s7 ¿° ©14¹ ¯s¿ ©8¹ ¯° s1 ¿° ©10¹ ¯° s2 ¿° © 280¹ ¯° s7 ¿° Finally, using the transform pairs established in Table 2.1, we have The Inverse Laplace Transform 151 ª º 1 1 t 3 2t 29 7t 4s 1 L1 « e e e . » 10 280 «¬ s s 1 s 2 s 7 »¼ 14 8 1 Example 2.20. Determine L ª¬ F s º¼ , where F s ª º s3 5s 2 6s 7 « » «¬ s s 1 s 3 6 s 2 11s 6 »¼ . Solution: Step 1, the denominator is in the factored form F s ª º s3 5s 2 6s 7 « » «¬ s s 1 s 1 s 2 s 3 »¼ . In step 2, we use partial fraction expansion and decompose the function into five terms. We begin by finding the partial fraction expansion for F s . The denominator consists of five distinct linear factors and the expansion has the form s 3 5s 2 6 s 7 s s 1 s 1 s 2 s 3 A B C D E s s 1 s 1 s2 s3 where A, B, C, D, and E are real numbers to be determined. Chapter 2 152 ª º s 3 5s 2 6 s 7 7 , A « » «¬ s 1 s 1 s 2 s 3 »¼ s 0 6 ª s 3 5s 2 6 s 7 º 9 B « , » ¬« s s 1 s 2 s 3 ¼» s 1 24 C D E ª s 3 5s 2 6 s 7 º 5 , « » «¬ s s 1 s 2 s 3 »¼ s 1 4 ª s 3 5s 2 6 s 7 º 11 , « » ¬« s s 1 s 1 s 3 ¼» s 2 2 ª s 3 5s 2 6 s 7 º « » «¬ s s 1 s 1 s 2 »¼ s 3 hence, the given function F s 3 5s 2 6 s 7 s s 1 s 1 s 2 s 3 . 83 , 24 s can be expanded as § 7 · 1 § 9 · 1 § 5 · 1 § 11 · 1 § 83 · 1 ¨ ¸ ¨ ¸ ¨ ¸ ¨ ¸ ¨ ¸ 6 s 24 s 1 4 s 1 2 s 2 © ¹ © ¹ © ¹ © ¹ © 24 ¹ s 3 In step 3, we find the inverse Laplace transform of each term. Now that we have obtained the partial fraction expansion, taking the inverse Laplace transform of each term on the right and using the linearity property of the Laplace transform, we find that § 7 · ­ 1 ½ § 9 · ­° 1 ½° § 5 · 1 ­° 1 ½° § 11 · 1 ­° 1 ½° § 83 · 1 ­° 1 ½° F s ¨ ¸ L1 ® ¾ ¨ ¸ L1 ® ¾¨ ¸L ® ¾¨ ¸L ® ¾¨ ¸L ® ¾ © 6 ¹ ¯ s ¿ © 24 ¹ °¯ s 1 °¿ © 4 ¹ °¯ s 1 °¿ © 2 ¹ °¯ s 2 °¿ © 24 ¹ °¯ s 3 °¿ Finally, using the transform pairs established in Table 2.1, we have The Inverse Laplace Transform 153 7 9 t 5 t 11 2t 83 3t e e e e . 6 24 4 2 24 f t 2.7.2 Partial Fractions: Repeated Linear Factors ª º s2 1 Example 2.21. Determine L « ». 2 «¬ s 2 s 1 »¼ 1 Solution: Since s 1 is a repeated linear factor with multiplicity 2 and s 2 is a non-repeated linear factor, the partial fraction expansion has the form s2 1 F s s 1 2 s2 A B C 2 s 1 s 1 s2 where A, B, and C are real numbers to be determined. We begin by multiplying both sides by s2 1 A s 1 s 2 B s 2 C s 1 Setting s s s 1 2 0 B 2 C 5 A 4 hence, the given function F 2 s 2 s 1 to obtain s can be expanded as 2 Chapter 2 154 ª º s2 1 « » 2 «¬ s 1 s 2 »¼ 4 2 5 2 s 1 s 1 s2 . Taking the inverse Laplace transform of each term on the right, and using the linearity property of the Laplace transform, we find that ª º ­ 1 °½ s2 1 ­° 1 ½° ­ 1 ½ 1 ° « » 4 L1 ® L 5L1 ® ¾ 2L ® ¾ 2 2¾ ¯ s 1¿ «¬ s 1 s 2 »¼ °¯ s 2 °¿ ¯° s 1 ¿° 1 . Finally, using the transform pairs established in Table 2.1, we have ª º s2 1 » 4e t 2te t 5e 2t . L « 2 «¬ s 1 s 2 »¼ 1 Example 2.22. Determine (a ) ª s 2 9s 2 º L1 « » 2 «¬ s 3 s 1 »¼ 1 (b) L ª s 1 º . « 2» ¬« s 1 s ¼» Solution: (a) Since s 1 is a repeated linear factor with multiplicity two and s 3 is a non-repeated linear factor, the partial fraction expansion has the form The Inverse Laplace Transform ª s 2 9s 2 º « » 2 «¬ s 1 s 3 »¼ 155 A B C 2 s 1 s 1 s3 where A, B, and C are real numbers to be determined. We begin by multiplying both sides by s 2 9s 2 2 s 3 s 1 to obtain A s 1 s 3 B s 3 C s 1 2 Setting B 3 s 1 s 3 C 1 s 0 A 2 hence, we have ª s 2 9s 2 º « » 2 «¬ s 1 s 3 »¼ 2 3 1 2 s 1 s 1 s3 . Applying the inverse Laplace transform to the above equation, and using its linearity, we get the following result ª s 2 9s 2 º » 2et 3tet 2e 3t L « 2 «¬ s 1 s 3 »¼ 1 Chapter 2 156 (b) Since s is a repeated linear factor with a multiplicity of two and s 1 is a non-repeated linear factor. The partial fraction expansion has the form s 1 2 s s 1 A B C 2 s s s 1 . We begin by multiplying both sides by s 1 s 1 s 2 to obtain As s 1 B s 1 Cs 2 Setting s 1 C 2 s 0 B 1 . Equating the coefficients of s 2 A C 0 A 2 . Hence, we have s 1 2 s s 1 2 1 2 2 s s s 1 Applying the inverse Laplace transform to the above equation, and using its linearity, we get the following result ª s 1 º t L1 « 2 » 2 t 2e . s s 1 «¬ »¼ The Inverse Laplace Transform 157 Example 2.23. Evaluate the inverse transform of 9 s 2 38s 55 F s s3 s2 3 Solution: Alternative Method: Compute partial fraction constants. Multiple poles pi of order m appear as a factor of the form m s pi in the denominator. These multiple poles produce m terms in decomposition. Cimi Ci1 Ci 2 Ci 3 ..... 2 3 m s pi s pi s pi s pi i mi Cij ¦ s p i 1 i The residues Cij are given by m j Cij 1 d i mi j ! ds mi j therefore, given F 9 s 2 38s 55 s3 s2 A 3 ^ s p mi i F s ` s pi , i 1, 2,3....mi s , we write C33 C32 C31 A 3 2 s 3 s2 s2 s2 ª 9 s 2 38s 55 º « » 3 «¬ »¼ s2 s 3 2 j . Chapter 2 158 C33 2 1 d0 ­ ° 9 s 38s 55 ½ ° ¾ 0 ® 3 3 ! ds ° s3 °s 2 ¯ ¿ 2 ­ ° 9 s 38s 55 ½ ° ® ¾ s3 ° °s 2 ¯ ¿ C32 2 1 d ­ ° 9 s 38s 55 ½ ° ® ¾ 3 2 ! ds ° s3 ° ¯ ¿s 2 1 C31 1 d2 ­ ° 9 s 38s 55 ½ ° ¾ 2 ® 3 1 ! ds ° s3 ° ¯ ¿s 2 2 2 Hence, the given function F 9 s 2 38s 55 s3 s2 s can be expanded as 2 3 1 2 3 2 s3 s2 s2 s2 3 Applying the inverse Laplace transform to the above equation, and using its linearity, we get the following result ª 9s 2 38s 55 º 3 » 2e 3t t 2 e 2t te2t 2e2t . L « 3 2 «¬ s 3 s 2 »¼ 1 Example 2.24. Evaluate the inverse transform of F s 3s 2 7 s 6 s 1 3 3 The Inverse Laplace Transform 159 Solution: 3s 2 7 s 6 s 1 C33 3 s 1 3 C32 s 1 C33 1 d0 3 3 ! ds 0 C32 1 d 3s 2 7 s 6 3 2 ! ds C31 1 d2 3 1 ! ds 2 ^ 3s 7s 6 ` 2 ^ 2 ` ^ 6s 7 ` s 1 2 s 1 1 3 s 1 . 3s 2 7 s 6 s 1 C31 s 1 s 1 ^ 3s 7s 6 ` Hence, the given function F F s 2 s can be expanded as 2 3 s 1 3 1 s 1 2 3 s 1 . Taking the inverse Laplace transform of each term on the right and using the linearity property of the Laplace transform, we find that L1 ª¬ F s º¼ ­ ­ 1 ° ½ ° 1 ½ ° 1 ­ ° 1 ½ ° ° 2 L1 ® L ® 3L1 ® ¾ 3¾ 2 ¾ ° ° ° ¯ s 1 ° ¿ ¯ s 1 ° ¿ ¯ s 1 ° ¿ Finally, using the transform pairs established in Table 2.1, we have f t Thus, t 2 et tet 3et . Chapter 2 160 t 2 t 3 et . f t Alternative method: To compute partial fraction constants, we write 3s 2 7 s 6 s 1 A 3 s 1 3 B s 1 2 C s 1 from which, 2 3s 2 7 s 6 A B s 1 C s 1 . If s = 1, we obtain A = 2, but we seem to have run out of convenient values with which to make substitutions. However, remember that whenever two functions are equal, so are their derivatives. Differentiating both sides of the above equation, we get 6s 7 B 2C s 1 so that s 1 can be used again, yielding B 1. Differentiating a second time, we obtain 6 2C C 3 Hence, the given function F F s 3s 2 7 s 6 s 1 3 s can be expanded as 2 s 1 3 1 s 1 2 3 s 1 Taking the inverse Laplace transform of each term on the right, and using the linearity property of the Laplace transform, we find that The Inverse Laplace Transform L1 ¬ª F s ¼º 161 ­ ­ 1 ° ½ ° 1 ½ ° 1 ­ ° 1 ½ ° ° 3L1 ® 2 L1 ® L ® ¾ 3¾ 2 ¾ ° s 1 ¿ ° ° ° ¯ ¯ s 1 ° ¿ ¯ s 1 ° ¿ Finally, using the transform pairs established in Table 2.1, we have f t t 2 et tet 3et . The differentiation procedure works particularly well with repeating linear factors. s5 Example 2.25. Evaluate the inverse transform of F s s 1 s3 . Solution: Alternative method: Compute partial fraction constants. Multiple poles pi of order m appear as a factor of the form s pi in the denominator. These multiple poles produce m terms in decomposition. Cimi Ci1 Ci 2 Ci 3 ..... m 2 3 s pi s pi s pi s pi i mi Cij ¦ s p i 1 i The residues Cij are given by m j Cij 1 d i mi j ! ds mi j therefore, given F ^ s p s , we write i mi F s ` s pi , i 1, 2,3....mi j m Chapter 2 162 s5 s2 s 3 C C C A 33 32 31 3 2 s2 s s s ª s5 º « » 3 ¬ s ¼s 2 A 7 8 C33 1 d 0 °­ s 5 °½ ® ¾ 3 3 ! ds 0 ¯° s 2 ¿°s 0 °­ s 5 °½ ® ¾ ¯° s 2 ¿°s 0 C32 1 d °­ s 5 °½ ® ¾ 3 2 ! ds °¯ s 2 °¿s 0 7 4 C31 1 d 2 ­° s 5 ½° ® ¾ 3 1 ! ds 2 ¯° s 2 ¿°s 0 11 16 Hence, the given function F s5 s2 s 3 5 2 s can be expanded as 7 1 5 1 7 1 11 1 3 2 8 s 2 2 s 4 s 16 s . Applying the inverse Laplace transform to the above equation and using its linearity, we get the following result ­° s 5 ½° L1 ® 3¾ °¯ s 2 s °¿ 7 1 ­ 1 ½ 5 1 ­ 1 ½ 7 1 ­ 1 ½ 11 1 ­ 1 ½ L ® ¾ L ® ¾ L ® ¾ L ® ¾ 8 ¯ s 2 ¿ 2 ¯ s 3 ¿ 4 ¯ s 2 ¿ 16 ¯ s ¿ Finally, using the transform pairs established in Table 2.1, we have The Inverse Laplace Transform °­ s 5 °½ L1 ® 3¾ °¯ s 2 s °¿ 163 7 2t 5 2 7 11 e t t . 8 4 4 16 2.7.3 Partial Fractions: Quadratic Polynomials Case (i). A partial fraction corresponds to every single quadratic factor as 2 bs c of the denominator, As B , as bs c 2 here, A and B are constants. Case (ii). A partial fraction corresponds to every repeating quadratic factor n as 2 bs c of the denominator, A3 s B3 An s Bn A1s B1 A2 s B2 ......... n 2 3 2 as bs c as 2 bs c as 2 bs c as 2 bs c where Ai and Bi are constants. ª º 2 s 2 10 s ». Example 2.26. Determine L « 2 «¬ s 2 s 5 s 1 »¼ 1 Solution: We can see that the quadratic factor the linear factor s 2 2 s 5 is irreducible. Since s 1 appears to the first power in the denominator of Chapter 2 164 F s and the quadratic factor appears to the first power, the partial fraction expansion F s has the form ª º 2 s 2 10 s « 2 » ¬« s 2 s 5 s 1 »¼ ª º 2 s 2 10 s « » « s 1 2 22 s 1 » ¬« ¼» A s 1 B 2 s 1 2 2 C s 1 where A, B, and C are real numbers to be determined. 2s 2 10s 2 ª¬ A s 1 B º¼ s 1 C s 1 22 . Setting s s s 1 C 1 1 B 4 0 A 3 We have ª º 2 s 2 10 s « » « s 1 2 22 s 1 » ¬« ¼» ª º 2 s 2 10 s « » « s 1 2 22 s 1 » «¬ »¼ 3 s 1 4 2 s 1 2 2 1 s 1 ª º ª º s 1 2 « » « »ª 1 º 2 3 « s 1 2 22 » « s 1 2 22 » «« s 1 »» ¼ «¬ »¼ «¬ »¼ ¬ Taking the inverse Laplace transform of each term on the right, and using the linearity property of the Laplace transform, we find that The Inverse Laplace Transform 165 ª º ª º ª º 2s 2 10s s 1 2 » 3L1 « » 2 L1 « » L1 ª 1 º L1 « « » « s 1 2 22 s 1 » « s 1 2 22 » « s 1 2 22 » ¬« s 1 ¼» «¬ ¼» ¬« ¼» ¬« ¼» Finally, using the transform pairs established in Table 2.1, we have ª º 2 s 2 10 s « » L « s 1 2 22 s 1 » ¬« ¼» 1 3et cos 2t 2et sin 2t e t . ª 4s 2 s 1 º » Example 2.27. Determine L « «¬ s s 2 1 »¼ 1 Solution: We can see that the quadratic factor s 2 1 is irreducible. Since the linear factor s appears to the first power in the denominator of F s and the quadratic factor appears to the first power, the partial fraction expansion of F s has the form ª 4s 2 s 1 º « » «¬ s s 2 1 »¼ A Bs C 2 s s 1 where A, B, and C are real numbers to be determined. 4s 2 s 1 A s 2 1 s Bs C 4s 2 s 1 A B s2 C s A Chapter 2 166 Hence, comparing the coefficients of both sides, we have s2 : A B 4, s: C 1, 1: A 1. By solving these equations, we obtain A 1, B 3& C 1 Hence, ª 4 s 2 s 1 º 1 3s 1 « » «¬ s s 2 1 »¼ s s 2 1 . Taking the inverse Laplace transform of each term on the right and using the linearity property of the Laplace transform, we find that ª 4s 2 s 1 º » L « «¬ s s 2 1 ¼» 1 ­ s ° ½ ­ 1 ° ½ ° ­1 ½ 1 ° L1 ® ¾ 3L1 ® 2 ¾ L ® 2 ¾ ¯s¿ ° ° ¯ s 1 ° ¿ ¯ s 1 ° ¿ Finally, using the transform pairs established in Table 2.1, we have ª 4s 2 s 1 º » L « «¬ s s 2 1 »¼ 1 1 3cos t sin t . 1 Example 2.28. Determine L ª º s 1 « 2 ». «¬ s 1 s 2 9 »¼ The Inverse Laplace Transform 167 Solution: s 2 1 and s 2 9 are irreducible and appear to the first power in the denominator of F s . We can see that both the quadratic factors The partial fraction expansion for F s 1 2 2 s 1 s 9 s has the form As B Cs D 2 s2 1 s 9 where A, B, and C are real numbers to be determined. s 1 As B s 2 9 Cs D s 2 1 Comparing the coefficients of both sides, we have s3 : A C 0, s2 : B D 0, s: 9A C 1, 1: 9B D 1. Through the successive elimination of variables, we obtain A B 1 and C 8 Hence, we have D 1 . 8 Chapter 2 168 s 1 s2 1 s2 9 1 ª s 1 1 1 º s 1 º 1 ª s s « 2 » « 2 » 2 2 2 2 8 « s 1 s 9 » 8 « s 1 s 1 s 9 s 9 » ¬ ¼ ¬ ¼ Taking the inverse Laplace transform of each term on the right, and using the linearity property of the Laplace transform, we find that ­° ½° 1 ª ­° s ½° ­ 1 ½° ­ s ½° ­ 1 ½°º s 1 1 1 ° 1 ° 1 ° « L1 ® 2 L L L L ¾ ® 2 ¾ ® 2 ¾ ® 2 ¾ ® 2 ¾» 2 °¯ s 1 s 9 °¿ 8 «¬ °¯ s 1 °¿ °¯ s 1 °¿ °¯ s 9 °¿ °¯ s 9 °¿»¼ Finally, using the transform pairs established in Table 2.1, we have ­° ½° s 1 L ® 2 ¾ 2 °¯ s 1 s 9 °¿ 1 1 >3cos t 3sin t 3cos 3t sin 3t @. 24 Example 2.29. Determine the inverse Laplace transform of F s 4s 2 6 s 1 s 2 2s 2 . Solution: We can see that the quadratic factor the linear factor s 2 2 s 2 is irreducible. Since s 1 appears to the first power in the denominator of F s and the quadratic factor appears to the first power, the partial fraction expansion for F s has the form The Inverse Laplace Transform 4s 2 6 F s 2 s 1 s 2s 2 169 A Bs C 2 s 1 s 2s 2 where A, B, and C are real numbers to be determined. 4s 2 6 A s 2 2 s 2 s 1 Bs C Setting s 1 A 2. Equating the coefficients of s B 2 and s , we get 2. 2 and C Hence, we have F s F s 4s 2 6 2 s 1 s 2s 2 4s 2 6 s 1 s 2 2s 2 2 2s 2 2 s 1 s 2s 2 2 s 1 4 2 2 s 1 s 1 1 . Taking the inverse Laplace transform of each term on the right, and using the linearity property of the Laplace transform, we find that ­ ½ ­ ½ ­° ½° 4s 2 6 ­ 1 ½° s 1 ° 1 ° 1 ° 1 ° 1 ° 2 2 4 L1 ® L L L ¾ ® ¾ ® ¾ ® ¾ 2 2 2 1 s 1 2 2 s s s ° s 1 1 ° ° s 1 1 ° ¯° ¿° ¯° ¿° ¯ ¿ ¯ ¿ Finally, using the transform pairs established in Table 2.1, we have Chapter 2 170 ­° ½° 4s 2 6 t t t L ® ¾ 2e 2e cos t 4e sin t. 2 °¯ s 1 s 2s 2 °¿ 1 1 Example 2.30. Evaluate L ª¬ F s º¼ where 4s 16 F s 2 s 4s 15 s 2 6s 13 Solution: Using partial fractions, we write 4s 16 F s 2 2 s 4 s 5 s 6s 13 As B Cs D 2 s 4s 5 s 6s 13 2 where A, B, and C are the real numbers to be determined. Multiplying both sides by the denominator of F 4 s 16 s , As B s 2 6 s 13 Cs D s 2 4 s 5 Comparing the coefficients of both sides gives s3 : A C 0, s2 : 6 A B 4C D 0, s: 13 A 6 B 5C 4 D 16 : 13B 5 D 16 . 4, . The Inverse Laplace Transform 171 By successive elimination of variables, we obtain A C 0 and B 2, D Hence, the given function F 2 F s 2 s 2 1 2 . s can be expanded as 2 2 s3 4 . Taking the inverse Laplace transform of each term on the right, and using the linearity property of the Laplace transform, we find that L ^F s ` 1 ª ­ ½ ­ ½º 1 1 ° 1 ° °» 1 ° « 2 L ® ¾ L ® ¾» 2 2 « s 2 1 s 3 4 ° ° ° °» «¬ ¯ ¿ ¯ ¿¼ . Finally, using the transform pairs established in Table 2.1, we have f t 2e 2t sin t e 3t sin 2t . ª º 1 » . «¬ s 1 s 2 4 »¼ 1 Example 2.31. Determine L « Solution: We can see that the quadratic factor s2 4 is irreducible. Since s 1 and s 2 4 are non-repeated factors, the partial fraction expansion has the form Chapter 2 172 ª º 1 « » «¬ s 1 s 2 4 »¼ A Bs C 2 s 1 s 4 Alternative Method: We can use the cover-up method to find A, B, and C, A ª 1 º « 2 » «¬ s 4 »¼ s 1 > Bs C @s 2i 2 Bi C 1 5 ª 1 º « » «¬ s 1 »¼ s 2i 1 1 2i 1 1 2i ­° 1 2i ½° 1 2 i ® ¾ ¯° 1 2i ¿° 5 5 Since the real and imaginary parts are equal on both sides, we get B 1 &C 5 1 5. Hence, we have ª º 1 « » «¬ s 1 s 2 4 ¼» 1 °­ 1 s 1 ½° s 1 °½ 1 °­ 1 ® ¾ ® ¾ 5 ° s 1 s2 4 ° 5 ° s 1 s2 4 s 2 4 °¿ ¯ ¿ ¯ . Taking the inverse Laplace transform of each term on the right, and using the linearity property of the Laplace transform, we find that The Inverse Laplace Transform ª º 1 » L1 « «¬ s 1 s 2 4 ¼» 173 1 ­° 1 § 1 · 1 § s · 1 § 1 · ½° ¸ L ¨ ¸¾ ®L ¨ ¸ L ¨¨ 2 ¸ ¨ s 2 4 ¸° 5 ° © s 1 ¹ s 4 © ¹ © ¹¿ . ¯ Finally, using the transform pairs established in Table 2.1, we have ª º 1 » L1 « «¬ s 1 s 2 4 »¼ 1­ t 1 ½ ®e cos 2t sin 2t ¾ . 5¯ 2 ¿ 1 Example 2.32. Determine L ª s º 1 «e ». s 1 s 2 ¼» ¬« Solution: Let F s 1 s 1 s 2 Using partial fractions, we get F s 1ª 1 1 º « » 3 ¬« s 1 s 2 ¼» . Applying the inverse Laplace transform to the above equation, and using its linearity, we get the following result f t then, L1 ª¬ F s º¼ 1 t e e 2t , 3 Chapter 2 174 ª º 1 L1 «e s » s 1 s 2 »¼ «¬ 1 t 1 e e 2 t 1 u t 1 . 3 1 Example 2.33. Determine L F s ª¬ F s º¼ , where ª 3s 1 º e2 s « 3 2 ¬ s 5s 6s »¼ . Solution: In step 1, the denominator is in the factored form F s ª º 3s 1 e 2 s « » «¬ s s 2 s 3 »¼ . In step 2, we use partial fraction expansion and decompose the function into three terms. We begin by finding the partial fraction expansion for F s . The denominator consists of three distinct linear factors and the expansion has the form 3s 1 s s2 s3 A B C s s2 s3 where A, B, and C are real numbers to be determined. The Inverse Laplace Transform ª º 3s 1 A « » «¬ s 2 s 3 »¼ s 0 C ª 3s 1 º « » «¬ s s 2 »¼ s 3 B ª 3s 1 º « » «¬ s s 3 »¼ s 2 5 , 2 8 , 3 hence, the given function F 3s 1 s s2 s3 1 , 6 175 s can be expanded as 1 1 5 1 8 1 6 s 2 s2 3 s3 . In step 3, we find the inverse Laplace transform of each term. Having obtained the partial fraction expansion, taking the inverse Laplace transform of each term on the right and using the linearity property of the Laplace transform, we find that ­° ½° 3s 1 L1 ® ¾ ¯° s s 2 s 3 ¿° 1 1 ­ 1 ½ 5 1 ­° 1 ½° 8 1 ­° 1 ½° L ® ¾ L ® ¾ L ® ¾ 6 ¯ s ¿ 2 ¯° s 2 ¿° 3 ¯° s 3 ¿° . Finally, using the second shifting rule and the transform pairs established in Table 2.1, we have ­° ½° § 1 5 2v 8 3 t 2 · 3s 1 L1 ®e 2 s ¾ ¨ e e ¸u t 2 . s s 2 s 3 °¿ © 6 2 3 ¹ °¯ Chapter 2 176 Example 1.34. Given the Laplace transform ª º 3s « ». «¬ s 2 s 3 »¼ F s Find the initial value of f finding f t t , by (i) the initial value theorem; (ii) L1 ª¬ F s º¼ . Solution: (i) by the initial value theorem, · °½ 3s °­ § lim ® s ¨ ¸¸ ¾ ¨ s of °¯ © s 2 s 3 ¹ °¿ f 0 lim ^s F s ` f 0 § § ·· 3s lim ¨ s ¨ ¸¸ s of ¨ ¨ s 1 2 s s 1 3 s ¸ ¸ ¹¹ © © s of § · 3 lim ¨ ¸ s of ¨ 1 2 s 1 3 s ¸ © ¹ . Thus, f 0 3. (ii) We use partial fraction expansion and decompose the function into three terms. We begin by finding the partial fraction expansion for F s . The denominator consists of two distinct linear factors and the expansion has the form The Inverse Laplace Transform F s 3s s2 s3 177 A B s2 s3 where A and B are real numbers to be determined. ª 3s º A « » «¬ s 3 »¼ s 2 6 , B hence, the given function F F s 3s s2 s3 ª 3s º « » «¬ s 2 »¼ s 3 6, s , can be expanded as 6 6 s2 s3 . Having obtained the partial fraction expansion, taking the inverse Laplace transform of each term on the right and using the linearity property of the Laplace transform, we find that ­ 1 °½ ­ 1 °½ 3s °­ °½ 1 ° 1 ° L1 ® ¾ 6 L ® ¾ 6L ® ¾ °¯ s 2 s 3 °¿ °¯ s 2 °¿ °¯ s 3 °¿ . Finally, using the second shifting rule and the transform pairs established in Table 2.1, we have f t 6e2t 6e3t . Example 1.35. Given the Laplace transform F s ª º s2 « ». «¬ s 1 s 2 s 3 »¼ Chapter 2 178 Find the initial value of f t , by (i) the initial value theorem (ii) finding f t L1 ª¬ F s º¼ . Solution: (i) by the initial value theorem, lim ^s F s ` f 0 f 0 s of ­° ª º ½° s2 lim ® s « » .¾ s of °¯ «¬ s 1 s 2 s 3 »¼ °¿ § § ·· § · s2 1 lim ¨ s ¨ ¸ ¸ lim ¨ ¸ s of ¨ ¨ s 1 1 s s 1 2 s s 1 3 s ¸ ¸ s of ¨ 1 1 s 1 2 s 1 3 s ¸ ¹¹ © ¹ © © Thus, f 0 1. (ii) We will use partial fraction expansion and decompose the function into three terms. We begin by finding the partial fraction expansion for F s . The denominator consists of three distinct linear factors and the expansion has the form F s ª º s2 « » «¬ s 1 s 2 s 3 »¼ A B C s 1 s2 s3 where A, B, and C are real numbers to be determined. The Inverse Laplace Transform ª º s2 A « » «¬ s 2 s 3 »¼ s 1 1 2 ª º s2 « » ¬« s 1 s 2 ¼» s 3 9 , 2 C hence, the given function F F s B , 179 ª º s2 « » «¬ s 1 s 3 »¼ s 2 4, s can be expanded as ª º s2 « » ¬« s 1 s 2 s 3 ¼» 1 1 1 9 1 4 2 s 1 s2 2 s3 Having obtained the partial fraction expansion, taking the inverse Laplace transform of each term on the right and using the linearity property of the Laplace transform, we find that ­° ½° 1 1 ­° 1 ½° ­ 1 ½° 9 1 ­° 1 ½° s2 1 ° L1 ® L ® ¾ ¾ 4L ® ¾ L ® ¾ °¯ s 1 s 2 s 3 °¿ 2 °¯ s 1 °¿ °¯ s 2 °¿ 2 °¯ s 3 °¿ . Finally, using the second shifting rule and the transform pairs established in Table 2.1, we have f t 1 t 9 e 4e 2t e 3t . 2 2 2.8 Convolutions It is often necessary to find the inverse transform of the product of two functions F s G s when inverse transforms f t and g t of Chapter 2 180 and G s F s are known. We shall see shortly that the inverse of F s G s is called the convolution of f and g. 2.8.1 Definition The convolution of two functions, f and g, is defined as t f t ³ f u g t u du. g t 0 2.8.2 Properties of Convolution Let f t , g t and h t be piecewise continuous on i f t g t g t f t , ii f t g t h t f t g t f t iii f t g t f t g t h t >0, f . Then, h t , h t . Proof. To prove the equation in (i), we begin with the definition t f t ³ f u g t u du. g t 0 Using the change of variables, w f t g t 0 t ³ f w g t w dw ³ f w g t w dw t , t u , we have 0 g t f t The Inverse Laplace Transform 181 which proves (i). The proofs of equations (ii) and (iii) are found in the exercises. Example 2.36. Compute a t 2 *cos t b sin t *cos t c t * et . Solution: a Convolution between two functions f and g is given by t f t ³ f u g t u du. g t 0 t f t g t t 2 cos t 2 ³ u cos t u du. 0 Using integration by parts, we get t 2 cos t ^ u 2 sin t u 2u cos t u 2sin t u Thus, t 2 cos t 2 t sin t . b Convolution between two functions f and g is given by t f t g t ³ f u g t u du. 0 t f t g t sin t cos t ³ sin u cos t u du. 0 (2.9) t `. 0 Chapter 2 182 Recall from trigonometry that sin A cos B 1 ªsin A B sin A B º¼ . 2¬ If we set A u and B t u , we can carry out the integration in Eq. (2.9) t t ³ sin u cos t u du. sin t cos t 0 sin t cos t 1 ^sin t sin 2u t `du 2 ³0 1 ^t sin t 0` 2 Thus, t sin t sin t cos t 2 . c The convolution between two functions f and g is given by t f t g t ³ f u g t u du. 0 t f t g t g t f t t et t u ³ u e du. 0 Recall from trigonometry that t t et et ³ u e u du. 0 The Inverse Laplace Transform 183 We can carry out the integration and get ^ et ue u e u t et ` t 0 Thus, t et et t 1. The convolution operation has various uses. We introduced one of the essential theorems concerning the use of Laplace transforms and convolution—the convolution theorem. The convolution theorem enables one to deduce the inverse Laplace transform of an expression. However, it must be expressed in the form of a product of functions, meaning that each inverse Laplace transform of the product is known, i.e., it expresses the relationship between the product of two Laplace transforms F G s and the convolution of their transform pairs f t s and and g t . 2.9 Convolution Theorem Let f t and g t be piecewise continuous on F s L ^ f t ` and G s i L^ f t L ^ g t ` . Then, g t` F s G s , or, equivalently, ii L1 ^ F s G s ` f t g t . >0, f and Chapter 2 184 Proof: Starting with the left-hand side of i , we use the definition of convolution L^ f t g t` f ªt º st e ³0 «¬ ³0 f t v g v dv »¼ dt. To simplify the evaluation of this iterated integral, we introduce the unit step function u t v and write L^ f t g t` f ³e st 0 using the fact that u t v ªt º « ³ u t v f t v g v dv » dt , ¬0 ¼ 0 , if v ! t. Reversing the order of integration gives L^ f t g t` f ª f st º g v ³0 «¬ ³0 e u t v f t v dt »¼ dv. (2.10) Recall from the first translation property in Section 1.5.3 that the integral in brackets in Eq. (2.10) equals e L^ f t g t` sv F s . Hence, f sv ³ g v e F s dv 0 The Inverse Laplace Transform L^ f t g t` f F s ³ g v e sv dv 0 . Thus, L^ f t g t` F s G s . This proves the theorem. Example 2.37. Using the convolution theorem, determine ª º s ». L1 « 2 «¬ s a 2 s 2 b 2 »¼ Solution: We express let F f t g t s ª s s2 a2 s 2 b2 s s a2 and G s 2 ­° ½° s L1 ® 2 2 ¾ cos at ¯° s a ¿° ­ ½ 1 ° ° L1 ® 2 2 ¾ ° ¯ s b ° ¿ ºª º s 1 » « »; «¬ s 2 a 2 »¼ «¬ s 2 b 2 »¼ as « 1 so that s b2 2 and 1 sin bt b 185 Chapter 2 186 In case i , if we suppose that a 2 z b 2 , then, using the convolution integral, we have L1 ^ F s G s ` t f t g t ³ f u g t u du 0 ª º s L « 2 2 2 2 » «¬ s a s b »¼ t 1 cos au sin b t u du. b ³0 1 (2.11) Recall from trigonometry that cos A sin B 1 ªsin A B sin A B º¼ . 2¬ If we set A au and B b t u , we can carry out the integration in Eq. (2.11) ª º s L1 « 2 2 2 2 » «¬ s a s b »¼ 1 sin a b u bt sin a b u bt du 2 ³0 ª º s L « 2 2 2 2 » «¬ s a s b »¼ 1 ­° cos a b u bt cos a b u bt ½° ® ¾ 2 ¯° a b ab ¿° 1 t ª º s « » L «¬ s 2 a 2 s 2 b 2 »¼ 1 This simplifies to ^ cos bt cos at . a 2 b2 ` t 0 The Inverse Laplace Transform ª º s » L1 « 2 «¬ s 4 s 2 9 »¼ 187 1­ 1 ½ ®cos 2t cos 3t ^cos 2t cos 3t `¾ 4¯ 5 ¿ Thus, ª º s » L1 « 2 «¬ s 4 s 2 9 »¼ In case ii If a 2 ª º s » L1 « « s2 a2 2 » ¬ ¼ 1 ^cos 2t cos 3t ` . 5 b 2 , then t 1 cos au sin a t u du. a ³0 (2.12) Recall from trigonometry that cos A sin B If we set A 1 ªsin A B sin A B º¼ . 2¬ au and B b t u , we can carry out the integration in Eq. (2.12) ª º s « » L « s2 a2 2 » ¬ ¼ 1 ^sin at sin 2au at `du b ³0 ª º s « » L « s2 a2 2 » ¬ ¼ cos 2au at ½ 1­ ®sin at u ¾ b¯ 2a ¿ 1 1 t t 0 Chapter 2 188 ª º s » L1 « « s2 a2 2 » ¬ ¼ t sin at . 2a Example 2.38. Using the convolution theorem, determine ª º 1 « ». L « s2 k 2 2 » ¬ ¼ 1 Solution: We express ª 1 s2 k 2 F s G s 2 ºª º 1 1 » « »; «¬ s 2 k 2 »¼ «¬ s 2 k 2 »¼ as « 1 s k2 2 so that f t g t ½° 1 1 ­° k L ® 2 2 ¾ k ¯° s k ¿° 1 sin kt k . We have the convolution theorem L1 ^ F s G s ` t f t g t ³ f u g t u du 0 ª º 1 « » L « s2 k 2 2 » ¬ ¼ 1 t 1 sin ku sin k t u du. k 2 ³0 (2.13) The Inverse Laplace Transform 189 Recall from trigonometry that sin A sin B 1 ªcos A B cos A B º¼ . 2¬ If we set A ku and B k t u , we can carry out the integration in Eq. (2.13) ª º 1 « » L « s2 k 2 2 » ¬ ¼ 1 (cos 2ku kt cos kt )du 2k 2 ³0 ª º 1 « » L « s2 k 2 2 » ¬ ¼ 1 ª1 º sin 2ku kt u cos kt » 2 « 2k ¬ 2k ¼0 1 1 t t . Thus, ª º 1 « » L « s2 k 2 2 » ¬ ¼ 1 1 ^sin kt kt cos kt `. 2k 3 Example 2.39. Using the convolution theorem, determine ª º 1 L1 « 2 » . «¬ s s a »¼ Solution: We express 1 s sa 2 ª 1 ºª 1 º »; 2 « ¬ s »¼ ¬« s a ¼» as « Chapter 2 190 let F f t s 1 and G s s2 ­1 ½ L1 ® 2 ¾ ¯s ¿ 1 so that sa t and g t ­° 1 ½° at L1 ® ¾ e . ¯° s a ¿° Using the convolution integral, we have t L1 ^ F s G s ` f t g t ³ f u g t u du 0 ª º 1 L1 « 2 » «¬ s s a »¼ t ³u e a t u du. 0 (2.14) ª º at t 1 au L « 2 » e ³ u e du. s s a «¬ »¼ 0 1 We can carry out the integration in Eq. (2.14). Therefore ª º 1 at 1 ªe at 1º¼ . L1 « 2 » 2 ¬ «¬ s s a »¼ a Example 2.40. Using the convolution theorem, determine ª º s « ». L « s2 4 2 » ¬ ¼ 1 The Inverse Laplace Transform 191 Solution: s2 4 let F ª 1 ºª s º »« »; «¬ s 2 4 »¼ «¬ s 2 4 »¼ s We express as « 2 1 and G s s 4 s s s 4 2 2 so that f t g t 1 1 ­° 2 ½° L ® ¾ 2 ° s 2 22 ° ¯ ¿ 1 sin 2t 2 ­ ½ s ° ° L1 ® 2 2 ¾ ° s 2 ¿ ° ¯ cos 2t and . Using the convolution integral, we have L ^F s G s ` 1 t f t g t ³ f u g t u du 0 ª º s « » L « s2 4 2 » ¬ ¼ 1 t 1 sin 2u cos 2 t u du. 2 ³0 Recall from trigonometry that sin A cos B 1 ªsin A B sin A B º¼ . 2¬ (2.15) Chapter 2 192 If we set A 2u and B 2 t u , we can carry out the integration in Eq. (2.15) ª º s » L1 « « s2 4 2 » ¬ ¼ 1 ^sin t sin 4u 2t ` du 4 ³0 ª º s « » L « s2 4 2 » ¬ ¼ cos 4u 2t 1 °­ t ®sin t u 0 4° 4 ¯ 1 t t ½° ¾ 0° ¿ which can be simplified to ª º s » L1 « « s2 4 2 » ¬ ¼ 1 t sin 2t. 4 Example 2.41. Using the convolution theorem, determine ª º s ». L1 « 2 «¬ s 4 s 2 9 »¼ Solution: We express let F s s s2 4 s2 9 1 and G s s 4 2 ª 1 ºª s º »« »; «¬ s 2 4 »¼ «¬ s 2 9 »¼ as « s s 9 2 The Inverse Laplace Transform so that f g t t 193 ­° 1 ½° 1 sin 2t and L1 ® 2 ¾ °¯ s 4 °¿ 2 ­ ½ s ° ° L1 ® 2 2 ¾ ° ¯ s 3 ° ¿ cos 3t . Using the convolution integral, we have L1 ^ F s G s ` t f t g t ³ f u g t u du 0 ª º s » L1 « 2 «¬ s 4 s 2 9 »¼ t 1 sin 2u cos 3 t u du. 2 ³0 (2.16) Recall from trigonometry that sin A cos B 1 ªsin A B sin A B º¼ . 2¬ If we set A 2u and B 3 t u , we can carry out the integration in Eq. (2.16) ª º s « » L «¬ s 2 4 s 2 9 »¼ 1 On integration, we get t 1 ^sin 3t u sin 5u 3t `du 4 ³0 . Chapter 2 194 t cos 5u 3t ½° t 1 ­° ®cos 3t u 0 ¾ 4° 5 °¿ 0 ¯ ª º s » L « 2 «¬ s 4 s 2 9 »¼ 1 which can be simplified to ª º s » L1 « 2 «¬ s 4 s 2 9 »¼ 1­ 1 ½ ®cos 2t cos 3t ^cos 2t cos 3t `¾ 4¯ 5 ¿ . Thus, ª º s » L1 « 2 «¬ s 4 s 2 9 »¼ 1 ^cos 2t cos 3t ` . 5 Example the 2.42. Using convolution ª º 1 L1 « 2 ». 2 «¬ s s 2 »¼ Solution: We express 1 s2 s 2 2 ª 1 ºª 1 º »; 2 ¬ s ¼ «¬ s 2 »¼ as « 2 » « Let F s So that 1 and G s s2 1 s2 2 . theorem, determine The Inverse Laplace Transform f t te2t t and g t t L ^F s G s ` 1 f t ³ f t u g u du g t 0 ª º 1 L1 « 2 » 2 «¬ s s 2 »¼ t ³ t u ue 2 u du. 0 On integration by parts, this gives ª º 1 L1 « 2 » 2 «¬ s s 2 »¼ 1 t 1 t 1 e 2t . 4 Example 2.43. Using the convolution theorem, determine ª º 1 ». L1 « «¬ s s 2 1 »¼ Solution: We express Let 1 s s2 1 1 and G s s F s so that f t ª1 º ª 1 º « »; ¬ s »¼ «¬ s 2 1 »¼ as « 1 and g t 1 s 1 2 sin t 195 Chapter 2 196 t L ^F s G s ` 1 f t g t ³ f t u g u du 0 ª 1 º » L « 2 «¬ s s 1 »¼ 1 t ³ sin u du. 0 Carrying out integration gives ª 1 º » L « 2 s s 1 «¬ »¼ 1 1 cos t . Example 2.44. Using the convolution theorem, determine ­° ½° 1 L1 ® 4 ¾. °¯ s 16 °¿ Solution: ª 1 ºª 1 º »« »; «¬ s 2 4 »¼ «¬ s 2 4 »¼ We express 1 4 s 16 let F 1 and G s s 4 then, s 2 as « 1 s 4 2 The Inverse Laplace Transform 197 ­ 1 ½ 1 L1 ^F s ` L1 ® 2 ¾ sin 2t ¯s 4¿ 2 and ­ 1 ½ 1 L1 ^G s ` L1 ® 2 ¾ sinh 2t . ¯s 4¿ 2 We have the convolution theorem t L1 ^ F s G s ` f t g t ³ f u g t u du 0 ª 1 º L « 4 ¬ s 16 »¼ 1 t 1 sinh 2u sin 2 t u du. 4 ³0 (2.17) We can carry out the integration in Eq. (2.17) t ª 1 º 1 ª¬cosh 2u sin 2 t u sinh 2u cos 2 t u º¼ 0 L1 « 4 » ¬ s 16 ¼ 16 . Thus, ª 1 º 1 L1 « 4 >sinh 2t sin 2t @. ¬ s 16 »¼ 16 Example 2.45. Using the convolution theorem, determine ­ 1 ½ L1 ® 2 ¾. ¯ 4s 9 ¿ Solution: We express 1 4s 2 9 ª 1 ºª 1 º »« »; «¬ 2 s 3 »¼ «¬ 2 s 3 »¼ as « Chapter 2 198 let F s 1 and G s 2s 3 1 2s 3 then, ­ 1 ½ L1 ^F s ` L1 ® ¾ ¯ 2s 3 ¿ 1 23 t e 2 3 ­ 1 ½ 1 2t L1 ^G s ` L1 ® e . ¾ ¯ 2s 3 ¿ 2 We have the convolution theorem t L1 ^ F s G s ` f t ³ f u g t u du g t 0 ª 1 º L1 « 2 ¬ 4 s 9 »¼ 3 3 u t u 1 2 2 e e du. ³ 40 t (2.18) We can carry out the integration in Eq. (2.18) ª 1 º L « 2 » ¬ 4s 9 ¼ 1 t 1 32 t e ³ e 3u du 4 0 Thus, 3 ª 1 º 1 2t L1 « 2 » e 1 e 3t . ¬ 4s 9 ¼ 12 Example 2.46. Using the convolution theorem, solve for f t integral equation f t 2t 2 ³ f t u e u dt. 0 t in the The Inverse Laplace Transform 199 Solution: Integral equations are equations in which the unknown function appears under the integral. If the derivatives of the function are also in the equation, then they are called integro-differential equations. We recognize the integral on the right as the convolution of f t with e t . Therefore, the integral equation has the form f t 2t 2 f t et . We apply the Laplace transform and the convolution theorem to this equation to get 4 1 F s . s3 s 1 F s Then F s 4 4 4 , which we invert to obtain f t 3 s s Example 2.47. Using the convolution theorem, solve for 2 2t 2 t 3 . 3 f t in the integral equation t f t 2e t ³ sin t u f u du 0 Solution: We recognize the integral on the right as the convolution of e t . Therefore, the integral equation has the form f t with Chapter 2 200 f t 2e t f t sin t . We apply the Laplace transform and the convolution theorem to this equation to get F s F s 2 1 F s 2 . s 1 s 1 2 s2 1 s2 s 1 . It is now necessary to invert F s and to accomplish this, some algebraic manipulation is necessary to identify the terms on the right using the entries in Table 2.1. When expressed in terms of partial fractions, after a little manipulation, F F s 2 s2 1 2 s s 1 s becomes 4 2 2 2 s s s 1 which we invert to obtain f t 2t 2 4e t . Example 2.48. Using the convolution theorem, solve for g t integral equation t g t 3t 2 e t ³ e t u g u du 0 . in the The Inverse Laplace Transform 201 Solution: We recognize the integral on the right as the convolution of g t with et . Therefore, form g t 3t 2 et g t the integral et equation has the . We apply the Laplace transform and the convolution theorem to this equation to get G s 6 1 1 G s . 3 s s 1 s 1 It is now necessary to invert G s . to accomplish this. Some algebraic manipulation is necessary to identify the terms on the right using the entries in Table 2.1. When expressed in terms of partial fractions, after a little manipulation, G s . becomes G s 6 6 1 2 s3 s 4 s s 1 which we invert to obtain f t 3t 2 t 3 1 2e t . 2.10 Integral and Integro-differential Equations Equations with unknown functions under the integral are termed integral equations. If the equation also contains derivatives, then it is termed an integro-differential equation. Such equations are usually difficult to solve. However, if the integrals are in the form of a convolution, then we can use Laplace transforms to solve them. The following example shows how to Chapter 2 202 apply the Laplace transform method to arrive at the general solution of integro-differential equations using the convolution theorem. Example 2.49. Using the convolution theorem, solve for f t in the integro-differential equation df t dt y t t 3³ f t u e 2u du y t , f 0 4 0 0 t 1 ­0 ® 2t t !1 ¯4e . Solution: Equations containing an unknown function within the integral are termed integral equations. If there are also derivatives in the equation, then it is called an integro-differential equation. Using the second-shifting property and Table 2.1, we find the Laplace transform of y t , Y s 4e2e s s2 . Applying the Laplace transform to both sides of the integro-differential equation, we get t ­° df t ½° 3³ f t u e 2u du ¾ Y s L® 0 ¯° dt ¿° . Applying the convolution theorem to this equation, we get The Inverse Laplace Transform sF s 4 F s 4e2 e s s2 3F s s2 4e2 e s s 2 2s 3 s 2 2s 3 . 4 s2 Then, 4e 2 e s s 1 s 3 s 1 s 3 4 s2 F s Let 4 s2 F1 s . s 1 s 3 Using partial fractions, we get 3 1 . s 1 s 3 F1 s Since Let F2 f1 t L1 ª¬ F s ¼º 4 s s 1 s 3 3et e 3t , . Using partial fractions, we get F2 s since 1 1 s 1 s 3 f2 t et e 3t , then finally we invert to obtain 203 Chapter 2 204 ª 4 s2 4e 2 e s º L1 « » s 1 s 3 ¼» ¬« s 1 s 3 3et e 3t e 2 e t 1 e 3 t 1 u t 1 3et e 3t e 2 e t 1 e 3 t 1 u t 1 . f t Example 2.50. Compute L ^ f t * g t ` for the signals shown in figures 2.2a and b. f(t) g(t) 1 1 0 1 (a) t 0 1 (b) t Figure 2.2 Solution: The mathematical expression for the functions is given below f t ­1 0 d t d 1 u t u t 1 ® ¯0 t ! 1 and g t ­t ® ¯1 0 d t d1 t !1 We have the convolution theorem L^ f t g t` F s G s (2.19) The Inverse Laplace Transform 205 Using the second-shifting property and Table 2.1, we find the Laplace transform of f F s t and g t , which is 1 e s and F s s 1 e s s2 . Eq. (2.19) becomes L^ f t § 1 e s · § 1 s · ¨ ¸¨ 2 1 e ¸ ¹ © s ¹© s g t` F s G s g t` 2 1 1 e s . 3 s Thus, L^ f t Example 2.51. Compute f t F s i 1 sa sb by Partial fractions. ii Convolution theorem. iii Bromwich integral. Solution: i By partial fractions. L1 ^ F s ` where Chapter 2 206 We begin by finding the partial fraction expansion for F s . The denominator consists of two distinct linear factors and the expansion has the form F s 1 sa sb A B sa sb where A and B are real numbers to be determined ª 1 º A « » «¬ s b »¼ s a ª 1 º 1 B « » ba «¬ s a »¼ s b , 1 a b Hence, F s 1 sa sb 1 ª 1 º 1 ª 1 º « » « » b a «¬ s a »¼ b a «¬ s b »¼ . Taking the inverse Laplace transform of each term on the right, and using the linearity property of the Laplace transform, we find L1 ª¬ F s º¼ ª 1 º ª 1 º 1 1 L1 « L1 « » » ba «¬ s a »¼ b a «¬ s b »¼ . Finally, using the transform pairs established in Table 2.1, we have ª º 1 L1 « » «¬ s a s b »¼ 1 e bt e at . a b The Inverse Laplace Transform 207 ii Convolution theorem. We express F let F1 s s ª 1 ºª 1 º »« »; ¬« s a ¼» ¬« s b ¼» 1 as « sa sb 1 and F2 s sa 1 . sb Then, ­ 1 ½ at L1 ^F1 s ` L1 ® ¾ e ¯s a¿ and ­ 1 ½ bt L1 ^F2 s ` L1 ® ¾ e ¯s b¿ . We have the convolution theorem L ^ F1 s F2 s ` 1 t f1 t f2 t ³ f u f t u du 1 2 0 ª º 1 L « » ¬« s a s b ¼» 1 t au b t u ³e e du 0 (2.20) We can carry out the integration in Eq. (2.20) ª º 1 L « » «¬ s a s b »¼ 1 Thus, t au b t u ³e e 0 du Chapter 2 208 ª º 1 L1 « » «¬ s a s b »¼ 1 e bt e at . a b iii By Bromwich integral. Let F 1 s sa sb , Then, e st , sa sb e st F s a & s b . Both are simple poles the poles in F s are s Re s ^ a ` lim e st F s s a s o a Re s ^ b ` lim e st F s s b s o b st ­ ½ at ^ ` lim ® se b ¾ be a ^ ` lim ® se a ¾ ae b s o a ­ s o b ¯ ¿ st ¯ ½ bt ¿ Using the Bromwich integral V jf f t 1 e st F s ds 2S j V ³jf ¦ sum of residues 1 e bt e at . a b The Inverse Laplace Transform Example 2.52. Compute f t F s 1 s 2 s 3 209 L1 ^ F s ` where by i Partial fractions. ii Convolution theorem. iii Bromwich integral. Solution: i Partial fractions. We begin by finding the partial fraction expansion for F s . The denominator consists of two distinct linear factors and the expansion takes the following form F s 1 s 2 s 3 A B s2 s3 where A and B are real numbers to be determined ª 1 º A « » ¬« s 3 ¼» s 2 Hence, 1 , B ª 1 º 1 « » ¬« s 2 ¼» s 3 Chapter 2 210 1 F s s 2 s 3 ª 1 º ª 1 º « »« » «¬ s 2 »¼ «¬ s 3 »¼ . Taking the inverse Laplace transform of each term on the right, and using the linearity property of the Laplace transform, we find ª 1 º 1 ª 1 º L1 ª¬ F s º¼ L1 « »L « » «¬ s 2 »¼ «¬ s 3 »¼ . Finally, using the transform pairs established in Table 2.1, we have ª º 1 L1 « » «¬ s 2 s 3 »¼ e 3t e 2 t . ii Convolution theorem. F s let F1 1 and F2 s s2 s ª 1 We express s 2 s 3 1 ºª 1 º »« »; «¬ s 2 »¼ «¬ s 3 »¼ as « 1 s 3 then ­ 1 ½ 2t L1 ^F1 s ` L1 ® ¾ e ¯s 2¿ ­ 1 ½ 3t L1 ^F2 s ` L1 ® ¾ e ¯ s 3¿ . and The Inverse Laplace Transform 211 We have the convolution theorem L1 ^ F1 s F2 s ` t f1 t ³ f u f t u du f2 t 1 2 0 ª º 1 L1 « » «¬ s 2 s 3 »¼ t 2 u 3 t u ³e e du 0 (2.21) We can carry out the integration in Eq. (2.21) ª º 3t t u 1 L1 « » e ³ e du «¬ s 2 s 3 »¼ 0 Thus, ª º 1 L1 « » «¬ s 2 s 3 »¼ e 3t e 2 t . iii Bromwich Integral. Let F s 1 s 2 s 3 , then, e F s e st , s2 s3 the poles of F s are s st 2 &s 3 . Both are simple poles Chapter 2 212 ^ Re s ^ 2 ` lim e F s s 2 s o2 st ^ Re s ^ 3 ` lim e st F s s 3 s o3 ` ­ e st ½ lim ® ¾ s o2 s 3 ¯ ¿ ­ st ½ e 2 t ` lim ® se 2 ¾ e s o3 ¯ 3t ¿ . Using the Bromwich Integral V jf f t 1 e st F s ds ³ 2S j V jf Example 2.53. Compute f t F s ¦ sum of residues L1 ^ F s ` where 1 by s s 4 2 i Partial fractions. ii Convolution theorem. Solution: i Partial fractions. We can take the partial fractions two ways F s 1 s s 4 2 A Bs C s s2 4 1 A s 2 4 Bs C s e 3t e 2 t . The Inverse Laplace Transform 213 Hence, comparing the coefficients of both sides, we find s2 : A B 0, s: C 0, 1: A 1 4. Using these equations, we obtain A B 1 and C 4 0. Hence, we have F s 1 s s2 4 1 ª1 s º « 2 » 4 «s s 4 » ¬ ¼. Taking the inverse Laplace transform of each term on the right, and using the linearity property of the Laplace transform, we find that L1 ª¬ F s º¼ 1 1 ª 1 º 1 1 ª s º » L « L 4 «¬ s »¼ 4 « s 2 4 » ¬ ¼ Finally, using the transform pairs established in Table 2.1, we have f t 1 ^1 cos 2t `. 4 Alternative method: Chapter 2 214 We begin by finding the partial fraction expansion for F s . The denominator consists of two complex roots, linear factors, and the expansion has the form 1 s s 4 F s 1 s s 2i s 2i 2 A B B s s 2i s 2i Where A and B are real numbers to be determined A B ª 1 º « 2 » «¬ s 4 »¼ s 0 ª º 1 « » «¬ s s 2i »¼ s 2i 1 , B 4 ª º 1 « » ¬« s s 2i ¼» s 2i 1 8i 2 1 , 8 1 8 Hence, F s 1 s s 4 2 1 s s 2i s 2i 11 1 1 1 1 4 s 8 s 2i 8 s 2i . Taking the inverse Laplace transform of each term on the right, and using the linearity property of the Laplace transform, we find that f t ­° ½° 1 ­ 1 ½ 1 ­° 1 ½° 1 ­° 1 ½° 1 1 L1 ® 2 L1 ® ¾ L1 ® ¾ ¾ L ® ¾ °¯ s s 4 °¿ 4 ¯ s ¿ 8 ¯° s 2i ¿° 8 ¯° s 2i ¿° Finally, using the transform pairs established in Table 2.1, we have The Inverse Laplace Transform f t ­° 1 ½° 1 1 1 ei 2 t e i 2 t L1 ® 2 ¾ 8 °¯ s s 4 °¿ 4 8 Thus, f t ­° ½° 1 1 ei 2t e i 2t 1 L ® 2 ¾ 4 4 2 s s 4 °¯ °¿ f t ­° 1 ½° 1 L ® 2 1 cos 2t . ¾ °¯ s s 4 °¿ 4 1 1 ii Convolution theorem. We express º 1 1 ª 1 as ª º « «¬ s »¼ s 2 4 » ; s s2 4 «¬ »¼ Let F s 1 and G s s 1 s 4 2 so that f t 1 and g t L1 ^ F s G s ` 1 sin 2t 2 t f t g t ³ f t u g u du 0 215 Chapter 2 216 ª º 1t 1 » L1 « 2 ³ sin 2u du. «¬ s s 4 »¼ 2 0 Carrying out integration gives ª º 1 t 1 » cos 2u 0 L1 « 2 «¬ s s 4 »¼ 4 ª º 1 « » L 2 s s 4 «¬ »¼ 1 1 1 cos 2t . 4 Example 2.54. Compute f t F s s 2 L1 ^ F s ` where 1 by s4 i Partial fractions. ii Convolution theorem. Solution: i Partial fractions. We can take the partial fractions in two ways. F s 1 s 4 s2 A B C 2 s4 s s The Inverse Laplace Transform 1 As 2 B s 4 s C s 4 217 . Hence, comparing the coefficients of both sides, we get s2 : A B 0, s: 4B C 1: 4C 0, 1. Using these equations, we obtain A B 1 and C 16 1 . 4 Hence, F s 1 s 4 s2 1 1 1 1 1 1 16 s 4 16 s 4 s 2 Taking the inverse Laplace transform of each term on the right, and using the linearity property of the Laplace transform, we find L1 ¬ª F s ¼º 1 1 °­ 1 °½ 1 1 ­ 1 ½ 1 1 ­ 1 ½ L ® ¾ L ® ¾ L ® ¾ 16 °¯ s 4 °¿ 16 ¯ s ¿ 4 ¯ s 2 ¿ Finally, using the transform pairs established in Table 2.1, we have L1 ª¬ F s º¼ 1 4t 1 1 e t. 16 16 4 Another way to take partial fractions is to note that Chapter 2 218 1 s 4 s2 C C A 22 21 2 s4 s s 1 ª1º A « 2» ¬ s ¼ s 4 16 C22 d 0 ­° 1 ½° ® ¾ ds 0 ¯° s 4 ¿°s 0 ­° 1 ½° ® ¾ ¯° s 4 ¿°s 0 C21 1 d °­ 1 °½ ® ¾ 3 2 ! ds °¯ s 4 °¿s 0 1 16 1 4 . Hence, we have F s 1 s 4 s2 1 1 1 1 1 1 16 s 4 16 s 4 s 2 Taking the inverse Laplace transform of each term on the right, and using the linearity property of the Laplace transform, we find L1 ¬ª F s ¼º 1 1 ­° 1 ½° 1 1 ­ 1 ½ 1 1 ­ 1 ½ L ® ¾ L ® ¾ L ® ¾ 16 ¯° s 4 ¿° 16 ¯ s ¿ 4 ¯ s 2 ¿ . Finally, using the transform pairs established in Table 2.1, we have ª º 1 4t 1 L1 « e 4t 1 . 2» «¬ s 4 s »¼ 16 The Inverse Laplace Transform 219 ii Convolution theorem. We express 1 and G s s4 Let F s so that f s2 ª 1 ºª 1 º 1 as « » « 2 »; s4 «¬ s 4 ¼» ¬ s ¼ t e 4t and g t 1 s2 t t L ^F s G s ` 1 f t g t ³ f t u g u du 0 ª º 1 L1 « 2» ¬« s 4 s ¼» t ³e 4 t u udu 0 ª º 4 t t 4u 1 L « e ³ e udu 2» 0 ¬« s 4 s ¼» . 1 Carrying out integration gives ª º 1 4t 1 L1 « e 4t 1 . 2» ¬« s 4 s ¼» 16 Summary In this chapter, we have described and explained the properties of the inverse Laplace transform and the convolution theorem: 220 Chapter 2 x We started with a definition of the inverse Laplace transform and presented some standard functions in a table. The formula for the inverse Laplace transform uses a contour integration, which has been illustrated using simple solved examples. This contour integration is a little difficult to solve. An evaluation of the inverse Laplace transform using the partial fraction method for distinct linear factors, repeated linear factors, and quadratic factors has been given with several examples. x A definition of the convolution between two functions has been stated and the properties of convolution, including its commutative, distributive, and associative characteristics, have been stated and proved. Convolution between two functions has been illustrated using simple solved examples. Convolution of two time-domain functions results in the multiplication of their Laplace transforms in the frequency domain. The convolution theorem is useful for finding the inverse Laplace transform of the product of two functions in the frequency domain. Evaluation of the inverse Laplace transforms using the convolution theorem has also been explained with several examples. CHAPTER 3 APPLICATION OF THE LAPLACE TRANSFORM TO LTI DIFFERENTIAL SYSTEMS: TRANSFER FUNCTIONS 3.1 Introduction This chapter describes mathematical models for certain electrical circuits. These models describe the relationship between voltage and current (Kirchhoff’s laws) in a circuit. The properties of resistance, inductance, and capacitance are assumed to be due to the devices present at specific locations in the circuit and the connecting wires are ideal conductors. Such linear elements in circuit models yield linear, time-invariant differential equations with constant coefficients. We also cover some mechanical systems that are described by similar linear ordinary differential equations with constant coefficients, which should provide physical intuition for analogous circuits and their components. These mathematical models represent the input/output characteristics of the electrical and mechanical system. We will mainly limit ourselves to systems described by ordinary linear differential equations with constant coefficients and with initial conditions all assumed to be equal to zero. The transfer function H is a rational function of s s and the impulse response can thus be determined by transforming this back to the time domain. Newton’s laws Chapter 3 222 (for the mechanical system) and Kirchhoff’s laws (for the electrical system) lead to mathematical models that describe the relationship between dynamical system inputs and outputs. One such model is the linear time-invariant differential equation in Eq. (3.1): dk y t ak ¦ dt k k 0 dkx t bk ¦ dt k k 0 N M (3.1) Many systems can be approximately described by this equation, which y t relates the output ak parameters and to the input x t by way of the system bk . The transfer function H s can be determined by partial fraction expansion followed by transformation back to the time domain. The response y t of the system to an arbitrary input x t is x t i.e y t h t * x t . In order to find the response y t a given input transform given by the convolution h t with for x t , it is often easier to first determine the Laplace X s of x t and subsequently to transform X back to the time domain. This is because Y s of s H s X s , and hence X s H s , is a rational function for a large class of inputs. The inverse Laplace transform y t of Y s can then immediately be determined by partial fraction expansion. This simple standard solution Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Transfer Functions 223 method is yet another advantage of the Laplace transform over other transforms. The transfer function for the linear time invariant system described by the differential equations treated in Section 3.3 shows that the initial conditions are always zero. In Section 3.4, we will show that the Laplace transform can equally well be applied to an electrical circuit to find the transfer function. Finally, in Section 3.5 we briefly describe how the Laplace transform can be used to find the transfer function for the mechanical system. LEARNING OBJECTIVES On reaching the end of this chapter, we expect that you: x Have understood and can apply The definition of the transfer function. x Can find the input-output relations using the transfer function. x Can find the transfer function of the linear time-invariant system described by differential equations. x Can find the transfer function of the electrical system. x Can find the transfer function of the mechanical system. 3.2 Transfer Functions The transfer function of a linear time-invariant system (LTI) is defined as the Laplace transform of the system output to the Laplace transform of the system input, assuming that the initial conditions are equal to zero Chapter 3 224 Input X (s) Transfer Function H(s) Output Y (s) Figure 3.1 Transfer Function T .F H s L > output @ L >input @ all initial conditions zero or ª L^ y t ` º « » «¬ L ^ x t ` »¼ ªY s º « » «¬ X s »¼ all initial conditions zero all initial conditions zero H s . Using this equation, we can obtain the transfer function using any inputoutput pair x t y t . Indeed, if the input is an impulse G t , then its Laplace transform is 1 and the transfer function simply equals the Laplace transform of the corresponding output, which by definition is the impulse response. i Transfer functions are frequently used in engineering to characterize the input-output relationships of linear time-invariant systems. ii Transfer functions play an essential role in the analysis and design of LTI systems. Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Transfer Functions 225 3.3 Transfer Function of the Linear Time-invariant System Consider a linear time-invariant system characterized by the differential equation N ¦ ak k 0 dk y t dt k M ¦ bk k 0 dkx t dt k (3.2) where y t is the output to the input x t applied at time t 0. We use the differentiation and linearity properties of the Laplace transform to obtain the transfer function T .F H s Y s X s . Taking the Laplace transform, and with all the initial conditions assumed to be zero, we get N ¦ ak s k Y s k 0 Where M ¦b s X s . k k k 0 Y s Laplace transform of y t transform of x t y t . Therefore, N T .F H s Y s X s ¦a s k k k 0 M ¦b s k k k 0 . and X s Laplace Chapter 3 226 The following examples show how to use the Laplace transform method to obtain the transfer function of a linear time-invariant system (LTI) described by linear non-homogeneous differential equations with constant coefficients. 3.3.1 Definitions: Linear and Nonlinear nth-order Ordinary Differential Equations The general nth-order ordinary differential equation can be written symbolically as N ¦ ak t k 0 dk y t dt k f t . An nth-order ordinary differential equation is linear if it can be written in the form aN t dN y t d N 1 y t d2y t dy t a t a t ...... a1 t a0 t y t N 1 2 N N 1 2 dt dt dt dt aN t , aN 1 t ,......a1 t and a0 t f t , which are all functions of the independent variable t alone. A nonlinear ordinary differential equation is an ordinary differential equation that is not linear. From the definition, we can see that for an ordinary differential equation to be linear it is important that: (i) Each coefficient function ak t depends only on the dependent variable t and not on the independent variable y t . Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Transfer Functions (ii) The independent variable y t and all of its derivatives 227 y t occur algebraically to the first degree only. That is, the power of each term containing y and its derivatives is equal to 1. (iii) There are no terms that involve the product of either the independent y t variable and any of its derivatives or two or more of its derivatives. (iv) Functions of y t or any of its derivatives, such as y, log y, ev or sin y (nonlinear functions cannot appear in the equation). Example 3.1. Determine the transfer function H s of the system represented by the differential equation d3y t 2 dt 2 d2y t dt 2 dy t 2y t dt d 2x t dt 2 2 dx t dt x t . Solution: Let y ''' t 2 y '' t y ' t 2 y t x '' t 2 x ' t x t . Because of the linearity of the equation and of the Laplace transform operation, taking the Laplace transform of the differential equation, we have ^ ` ^ ` ^ ` ^ ` ^ ` L y ''' t 2 L y '' t L y ' t 2 L ^ y t ` L x '' t 2 L x ' t L ^ x t ` Chapter 3 228 Using the derivative property and assuming all initial conditions to be zero gives s3 2s 2 s 2 Y s s 2 2s 1 X s so that the system transfer function is given by Y s s 2 2s 1 X s s3 2s 2 s 2 . Thus, the transfer function H T .F H s s is Y s s 2 2s 1 X s s3 2s 2 s 2 . In this equation, we show the Laplace-transform solution of differential equations with constant coefficients, which transforms these differential equations into algebraic equations. We then solve the algebraic equations and use partial-fraction expansion to transform the solutions back into the time domain. For an equation in which the initial conditions are ignored, this method of solving the equations takes us to the transfer-function representation of LTI systems. The transfer-function approach is a standard procedure for the analysis and design of LTI systems. An important use of transfer functions is to determine the characteristics of an LTI system. Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Transfer Functions 229 Example 3.2. Determine the transfer function of the system represented by the differential equation d3y t dt 2 8 d2y t 5 dt 2 dy t dt 14 y t 4 dx t dt x t . Solution: Let y ''' t 8 y '' t 5 y ' t 14 y t 4 x' t x t . Because of the linearity of the equation and of the Laplace transform operation, taking the Laplace transform of the differential equation, we have ^ ` ^ ` ^ ` ^ ` L y ''' t 8 L y '' t 5 L y ' t 14 L ^ y t ` 4 L x ' t L ^ x t ` Using the derivative property, and assuming all initial conditions are zero, gives s 3 8s 2 5s 4 Y s 4s 1 X s so that the system transfer function is given by Y s X s 4s 1 s 3 8s 2 5s 14 . Thus, T .F H s Y s X s 4s 1 3 s 8s 2 5s 14 . Chapter 3 230 Example 3.3. Consider the initial value problem d2y t dt 2 dy t dt y t x t along with the initial conditions y 0 0 y' 0 , where x(t ) ­0 ° ®sin t °0 ¯ 0dt dS S t d 3S t t 3S (a) Determine the system transfer function H (b) Determine s . Y s . Solution: Assuming that the Laplace transform of the solution Y s exists, and using the fact that L is a linear operator, we take the Laplace transform of the above differential equation and write ­° d 2 y t dy t ½° L® y t ¾ L ^x t ` 2 dt ¯° dt ¿° L ª¬ y '' t º¼ L ª¬ y ' t º¼ L ª¬ y t º¼ X s ª¬ s 2Y s sy 0 y ' 0 º¼ ª¬ sY s y 0 º¼ Y s X s . Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Transfer Functions 231 Imposing the initial conditions, we obtain the Laplace transform of the solution as s2 s 1 Y s X s . Thus, the transfer function H H s Y s X s The function s is 1 s s 1 2 x t is continuous, but it is defined differently on the intervals. As such, the mathematical expression for the function is x(t ) ­0 ° ®sin t °0 ¯ 0dt dS S t d 3S t t 3S In terms of unit step functions, x t can be expressed as x(t ) x1 t ^ x2 t x1 t ` u t a ^ x3 t x2 t ` u t b x(t ) 0 sin t u t S sin t u t 3S . Then, taking the Laplace transform, L ^ x(t )` L ^sin t u t S ` L ^sin t u t 3S ` and on using the result in (1.7), we get Chapter 3 232 L ^ x(t )` eS s L ^ f1 (t )` e2S s L ^ f 2 (t )` f1 (t S ) sin t f 2 (t 3S ) sin t t S replace t (3.3) replace t t 3S f1 (t ) sin t S f1 (t ) sin t 3S f1 (t ) sin t f1 (t ) sin t then its Laplace transform is then its Laplace transform is L ^ f1 (t )` 1 s2 1 L ^ f 2 (t )` As such, Eq. (3.3) becomes § 1 · § 1 · L ^ x(t )` eS s ¨ 2 ¸ e2S s ¨ 2 ¸ © s 1 ¹ © s 1 ¹ thus, X s L ^ x(t )` 1 e 2S s e S s . s 1 2 We have Y s X s 1 s s 1 2 1 s2 1 Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Transfer Functions 233 X s Y s s2 s 1 1 e 2S s e S s . 2 2 s 1 s s 1 Y s Example 3.4. Determine the system response if the transfer function of the system is given by ª º s2 « 3 » «¬ s 6 s 2 11s 6 »¼ H s and if the unit step function is applied as an input. Solution: s2 s 3 6s 2 11s 6 H s . Given the input x t u t X s 1 s we have 1 s2 s s 3 6s 2 11s 6 Y s X s H s Y s s s 6 s 11s 6 3 2 s s 3 6s 2 11s 6 Chapter 3 234 It is now necessary to invert Y s . To accomplish this some algebraic manipulation is necessary if we are to identify the terms on the right with the entries in Table 2.1. When expressed in terms of partial fractions, after a little manipulation, Y Y s s becomes s s 1 s 2 s 3 A B C s 1 s2 s3 where A, B, and C are real numbers to be determined ª º s 1 A « ,B » «¬ s 2 s 3 »¼ s 1 2 ª º s 3 C « » ¬« s 2 s 1 ¼» s 3 2 ª º s « » «¬ s 1 s 3 »¼ s 2 2 . Hence, the given function Y Y s s can be expanded as s s 1 s 2 s 3 1 1 1 3 1 2 2 s 1 s2 2 s3 . Now that we have obtained the partial fraction expansion, taking the inverse Laplace transform of each term on the right and using the linearity property of the Laplace transform, we find y t ­ 1 °½ 3 1 °­ 1 °½ 1 1 °­ 1 °½ 1 ° L ® ¾ 2L ® ¾ L ® ¾ 2 °¯ s 1 °¿ °¯ s 2 °¿ 2 °¯ s 3 °¿ . Finally, using the transform pairs established in Table 2.1, we have Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Transfer Functions 235 1 t 3 e 2e 2 t e 3 t . 2 2 y t Example 3.6. Determine the system response if the transfer function of the system given by 4s 1 H s 3 s 8s 2 5s 4 if the unit step function is applied as an input. Solution: 4s 1 H s s 3 8s 2 5s 4 Given the input x t u t X s 1 s we have Y s Y s X s H s 4s 1 3 s s 8s 2 5s 14 4s 1 3 s s 8s 2 5s 14 It is now necessary to invert Y . s . To accomplish this, some algebraic manipulation is necessary if we are to identify the terms on the right with Chapter 3 236 the entries in Table 2.1. When expressed in terms of partial fractions, after a little manipulation, Y Y s s becomes 4s 1 A B C D s s 1 s2 s7 s s 1 s 2 s 7 where A, B, C, and D are real numbers to be determined. ª º 4s 1 A « » «¬ s 1 s 2 s 7 »¼ s 0 ª º 4s 1 « » «¬ s s 1 s 7 »¼ s 2 C B ª º 4s 1 « » «¬ s s 2 s 7 »¼ s 1 1 , 8 D ª º 4s 1 « » ¬« s s 1 s 2 ¼» s 7 29 280 1 , 14 3 , 10 . Hence, the given function Y Y s 4s 1 s s 1 s 2 s 7 s can be expanded as § 1 ·1 §1· 1 §3· 1 § 29 · 1 ¨ ¸ ¨ ¨ ¸ ¨ ¸ ¸ © 14 ¹ s © 8 ¹ s 1 © 10 ¹ s 2 © 280 ¹ s 7 . Taking the inverse Laplace transform of Y s and using Table 2.1 give us y t § 1 · § 1 · t § 3 · 2t § 29 · 7 t ¨ ¸ ¨ ¸e ¨ ¸e ¨ ¸e . © 14 ¹ © 8 ¹ © 10 ¹ © 280 ¹ Example 3.7. The impulse response h t of an LTI system is given by h t 1 et . Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Transfer Functions 237 a Determine the transfer function H s of the system. b Determine the response to the input x t e 2t . Solution: Given the impulse response h t of an LTI system h t 1 et , then the transfer function is H s L ª¬ h t º¼ H s ª1 1 º «¬ s s 1 »¼ 1 . s s 1 Given the input e 2t X s 1 s2 Y s X s H s 1 s s 1 s 2 Y s 1 s s 1 s 2 x t we have . It is now necessary to invert Y s . . To accomplish this, some algebraic manipulation is necessary if we are to identify the terms on the right with Chapter 3 238 the entries in Table 2.1. When expressed in terms of partial fractions, after a little manipulation, Y Y s s becomes 1 s s 1 s 2 A B C s s 1 s2 where A, B, and C are real numbers to be determined. ª º 1 A « » ¬« s 1 s 2 ¼» s 0 C ª 1 º « » «¬ s s 1 »¼ s 2 ª 1 º « » ¬« s s 2 ¼» s 1 1 , 1 2 Hence, the given function Y Y s 1 ,B 2 1 s s 1 s 2 s can be expanded as 11 1 1 1 2 s s 1 2 s 2 . Now that we have obtained the partial fraction expansion, we can consider the inverse Laplace transform of each term on the right-hand side and apply the Laplace transform’s linearity property. We arrive at y t 1 1 ­ 1 ½ 1 ­° 1 ½° 1 1 ­° 1 ½° L ® ¾ L ® ¾ L ® ¾ 2 ¯s¿ ¯° s 1 ¿° 2 ¯° s 2 ¿° . Finally, using the transform pairs established in Table 2.1, we have y t 1 t 1 2t e e . 2 2 Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Transfer Functions 239 Example 3.8. Use the Laplace transform to find the transfer function and the impulse response of the system if the differential equation describes the system d2y t dt 2 5 dy t dt d 2x t 6y t dt 2 8 dx t dt 13x t . Solution: Because of the linearity of the equation and the Laplace transform operation, taking the Laplace transform of the differential equation, we have ^ ` ^ ` ^ ` ^ ` L y '' t 5 L y ' t 6 L ^ y t ` L x '' t 8 L x ' t 13L ^ x t ` Using the derivative property, and assuming all initial conditions are zero, gives s 2 5s 6 Y s s 2 8s 13 X s Thus, the transfer function is given by T .F H s Y s s 2 8s 13 X s s 2 5s 6 . Note that the degree of the numerator is the same as the degree of the denominator. As such, we have to put it into fraction form so that we can apply partial fraction expansion H s 1 3s 7 s2 s3 1 A B s2 s3 . 240 Chapter 3 It is now necessary to invert H s . To accomplish this, some algebraic manipulation is necessary if we are to identify the terms on the right with the entries in Table 2.1. When expressed in terms of partial fractions, after a little manipulation, H H s 1 s becomes 1 2 s2 s3 Taking the inverse Laplace transform of H s and using Table 2.1 gives the result G t e 2t 2e 3t h t Example 3.9. Consider the causal LTI system described by the second differential equation d3y t dt 3 6 d2y t dt 2 11 dy t dt 6y t x t a Determine the transfer function H s . b Determine the impulse response h t . c Determine the output response for the input x t u t . d Determine the output response for the input x t G t . Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Transfer Functions 241 Solution: a The transfer function H s . Assuming that the Laplace transform of the solution Y s exists, and using the fact that L is a linear operator, we take the Laplace transform of the above differential equation and write 3 d2y t dy t °­ d y t L® 6 11 6y t 3 2 dt dt °¯ dt °½ ¾ L ^x t ` °¿ L ª¬ y ''' t º¼ 6 L ª¬ y '' t º¼ 11L ª¬ y ' t º¼ 6 L ª¬ y t º¼ s 3 6 s 2 11s 6 Y s Y s X s 1 s 3 6s 2 11s 6 The transfer function H H s H s X s Y s X s Y s X s s 1 s 6s 11s 6 3 2 1 s 1 s 2 s 3 b The impulse response h t . X s . 242 Chapter 3 It is now necessary to invert H s . To accomplish this, some algebraic manipulation is necessary if we are to identify the terms on the right with the entries in Table 2.1. When expressed in terms of partial fractions, after a little manipulation, H H s s becomes 1 s 1 s 2 s 3 A B C s 1 s2 s3 where A, B, and C are real numbers to be determined. ª º 1 A « » «¬ s 2 s 3 »¼ s 1 C ª º 1 « » ¬« s 1 s 2 ¼» s 3 Hence, the given function H H s 1 , 2 ª º 1 B « » «¬ s 1 s 3 »¼ s 2 1, 1 2 s can be expanded as 1 s 1 s 2 s 3 1 1 1 1 1 2 s 1 s2 2 s3 Now that we have obtained the partial fraction expansion, taking the inverse Laplace transform of each term on the right and using the linearity property of the Laplace transform, we find h t 1 1 ­° 1 ½° 1 ­° 1 ½° 1 1 ­° 1 ½° L ® ¾ L ® ¾ L ® ¾ 2 °¯ s 1 °¿ °¯ s 2 °¿ 2 °¯ s 3 °¿ Finally, using the transform pairs established in Table 2.1, we have Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Transfer Functions h t 243 1 t 2t 1 3t e e e 2 2 . c Output response for the input x t u t . We have Y s X s Y s 1 s 1 s 2 s 3 1 X s s 1 s 2 s 3 Given the input x t u t X s 1 s therefore Y s 1 s s 1 s 2 s 3 It is now necessary to invert Y s . To accomplish this, some algebraic manipulation is necessary if we are to identify the terms on the right with the entries in Table 2.1. When expressed in terms of partial fractions, after a little manipulation, Y s Y s becomes 1 s s 1 s 2 s 3 A B C D s s 1 s2 s3 where A, B, C, and D are real numbers to be determined. Chapter 3 244 ª º 1 A « » «¬ s 1 s 2 s 3 »¼ s 0 ª º 1 B « » ¬« s s 2 s 3 ¼» s 1 1 2 C ª º 1 « » ¬« s s 1 s 3 ¼» s 2 1 , 2 D ª º 1 « » ¬« s s 1 s 2 ¼» s 3 1 6 Hence, the given function Y s 1 , 6 . Y s can be expanded as 11 1 1 1 1 1 1 6 s 2 s 1 2 s 2 6 s 3 Now that we have obtained the partial fraction expansion, taking the inverse Laplace transform of each term on the right and using the linearity property of the Laplace transform, we find y t Y s 1 1 ­ 1 ½ 1 1 °­ 1 °½ 1 1 °­ 1 °½ 1 1 °­ 1 °½ L ® ¾ L ® ¾ L ® ¾ L ® ¾ 6 ¯ s ¿ 2 ¯° s 1 ¿° 2 ¯° s 2 ¿° 6 ¯° s 3 ¿° Finally, using the transform pairs established in Table 2.1, we have y t y t 1 1 t 1 2t 1 3t e e e . 6 2 2 6 Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Transfer Functions d Output response for the input x t 245 G t . We have Y s X s Y s 1 s 1 s 2 s 3 1 X s s 1 s 2 s 3 . Given the input xt G t X s 1 therefore Y s 1 . s 1 s 2 s 3 It is now necessary to invert Y s . To accomplish this, some algebraic manipulation is necessary if we are to identify the terms on the right with the entries in Table 2.1. When expressed in terms of partial fractions, after a little manipulation, Y s Y s becomes 1 s 1 s 2 s 3 A B C s 1 s2 s3 where A, B, and C are real numbers to be determined. 246 Chapter 3 ª º 1 A « » «¬ s 2 s 3 »¼ s 1 1 , 2 ª º 1 « » ¬« s 1 s 2 ¼» s 3 C Hence, the given function H 1 2 1, . s can be expanded as 1 s 1 s 2 s 3 Y s ª º 1 B « » «¬ s 1 s 3 »¼ s 2 1 1 1 1 1 2 s 1 s2 2 s3 Now that we have obtained the partial fraction expansion, taking the inverse Laplace transform of each term on the right and using the linearity property of the Laplace transform, we find 1 1 ­° 1 ½° 1 ­° 1 ½° 1 1 ­° 1 ½° L ® ¾ L ® ¾ L ® ¾ 2 ¯° s 1 ¿° ¯° s 2 ¿° 2 ¯° s 3 ¿° y t . Finally, using the transform pairs established in Table 2.1, we have 1 t 2t 1 3t e e e . 2 2 y t Example 3.10. Consider the initial value problem. d3y t dt 3 7 d2y t dt 2 e2t 4t along with the initial conditions Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Transfer Functions y 0 0 y' 0 247 y '' 0 . a Determine the system transfer function H s . b Determine Y s . Solution: (a) Assuming that the Laplace transform of the solution Y s exists, and using the fact that L is a linear operator, we take the Laplace transform of the above differential equation and write ­° d 3 y t d2y t L® 7 3 dt 2 ¯° dt ½° ¾ L ^x t ` ¿° L ª¬ y ''' t º¼ 7 L ª¬ y '' t º¼ X s ª¬ s 3Y s s 2 y 0 sy ' 0 y '' 0 º¼ ª¬ s 2Y s sy 0 y ' 0 º¼ . Imposing the initial conditions, we obtain the Laplace transform of the solution as s3 7s 2 Y s X s . Thus, the transfer function H H s Y s X s 1 s s7 2 s is X s Chapter 3 248 e 2t 4t b Let x t 1 4 2 s2 s X s L ^ x(t )` X s s 2 4s 8 . s2 s 2 s 2 4s 8 s2 s 2 We have Y s X s s 2 1 s7 X s Y s s2 s 7 s 2 4s 8 . s4 s 2 s 7 Y s Example 3.11. Consider the causal LTI system described by the second differential equation d2y t dt 2 5 dy t dt 6y t x t . a Determine the transfer function H s . b Determine the impulse response h t . c Determine the output response for the input x t u t . Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Transfer Functions d Determine the output response for the input x t 249 G t . Solution: a The transfer function H s . Assuming that the Laplace transform of the solution Y s exists, and using the fact that L is a linear operator, we take the Laplace transform of the above differential equation and write 2 dy t °­ d y t 5 6y t L® 2 dt °¯ dt °½ ¾ L ^x t ` °¿ L ª¬ y '' t º¼ 5 L ª¬ y ' t º¼ 6 L ª¬ y t º¼ s 2 5s 6 Y s Y s X s X s 1 s 2 5s 6 The transfer function H H s H s Y s . s is given by X s 1 s 2 5s 6 Y s 1 X s s2 s3 X s . Chapter 3 250 b The impulse response h t . It is now necessary to invert H s . To accomplish this, some algebraic manipulation is necessary if we are to identify the terms on the right with the entries in Table 2.1. When expressed in terms of partial fractions, after a little manipulation, H H s s becomes 1 s2 s3 A B s2 s3 where A and B are real numbers to be determined. ª 1 º 1, B A « » «¬ s 3 »¼ s 2 Hence, the given function H H s ª 1 º « » «¬ s 2 »¼ s 3 1 . s can be expanded as 1 1 s2 s3 Now that we have obtained the partial fraction expansion, taking the inverse Laplace transform of each term on the right and using the linearity property of the Laplace transform, we find that h t ­ 1 ½ 1 °­ 1 °½ L1 ® ¾ L ® ¾ ¯s 2¿ ¯° s 3 ¿° . Finally, using the transform pairs established in Table 2.1, we have Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Transfer Functions h t 251 e2t e3t . c Output response for the input x t u t . We have Y s 1 X s s2 s3 1 Y s X s s2 s3 Given the input x t 1 s u t X s therefore Y s 1 s s2 s3 It is now necessary to invert Y s . To accomplish this, some algebraic manipulation is necessary if we are to identify the terms on the right with the entries in Table 2.1. When expressed in terms of partial fractions, after a little manipulation, Y Y s s becomes 1 s s2 s3 A B C s s2 s3 where A, B, and C are real numbers to be determined. Chapter 3 252 ª º 1 A « » «¬ s 2 s 3 »¼ s 0 C ª 1 º « » «¬ s s 2 »¼ s 3 1 3 1 , 6 1 2 , . Hence, the given function Y Y s ª 1 º B « » «¬ s s 3 »¼ s 2 s can be expanded as 11 1 1 1 1 6 s 2 s2 3 s3 Now that we have obtained the partial fraction expansion, taking the inverse Laplace transform of each term on the right and using the linearity property of the Laplace transform, we find that y t 1 1 ­ 1 ½ 1 1 ­° 1 ½° 1 1 ­° 1 ½° L ® ¾ L ® ¾ L ® ¾ 6 ¯ s ¿ 2 °¯ s 2 °¿ 3 °¯ s 3 °¿ . Finally, using the transform pairs established in Table 2.1, we have y t 1 1 2t 1 3t e e . 6 2 3 d Output response for the input x t We have Y s 1 X s s2 s3 G t . Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Transfer Functions 1 Y s 253 X s s2 s3 . Given the input x t G t X s 1 therefore Y s 1 s2 s3 . It is now necessary to invert Y s . To accomplish this, some algebraic manipulation is necessary if we are to identify the terms on the right with the entries in Table 2.1. When expressed in terms of partial fractions, after a little manipulation, Y Y s s becomes 1 s2 s3 A B s2 s3 where A and B are real numbers to be determined. ª 1 º ª 1 º 1, B « A « » » «¬ s 2 ¼» s 3 ¬« s 3 ¼» s 2 Hence, the function Y Y s s can be expanded as 1 1 s2 s3 1 Chapter 3 254 Now that we have obtained the partial fraction expansion, taking the inverse Laplace transform of each term on the right and using the linearity property of the Laplace transform, we find that ­ 1 ½ 1 ­° 1 ½° L1 ® ¾ L ® ¾ ¯s 2¿ °¯ s 3 °¿ H t . Finally, using the transform pairs established in Table 2.1, we have e2t e3t . y t Example 3.12. Use the Laplace transform to find the transfer function and the impulse response of the system if the third-order differential equation describes the system d3y t dt 2 6 d2y t dt 2 11 dy t dt 6y t x t . Solution: Because of the linearity of the equation and the Laplace transform operation, taking the Laplace transform of the differential equation, we have 3 d2y t dy t °­ d y t L® 6 11 6y t 2 2 dt dt °¯ dt °½ ¾ L ^x t ` °¿ . Using the derivative property and assuming all initial conditions are zero gives Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Transfer Functions ^s 6s 11s 6 `Y s X s Thus, the transfer function H s is 3 H s 2 Y s X s . 1 s 6 s 11s 6 3 255 2 . The transfer function can be factored as H s 1 s 1 s 2 s 3 It is now necessary to invert H . s . To accomplish this, some algebraic manipulation is necessary if we are to identify the terms on the right with the entries in Table 2.1. When expressed in terms of partial fractions, after a little manipulation, H H s s becomes 1 s 1 s 2 s 3 A B C s 1 s 2 s3 where A, B, and C are real numbers to be determined. ª º ª º ª º 1 1 1 6 1 , B « . A « 1, C « » » » «¬ s 1 s 3 ¼» s 2 ¬« s 3 s 2 ¼» s 1 2 ¬« s 1 s 2 ¼» s 3 2 H s 1 1 1 1 1 2 s 1 s 1 2 s 2 . Taking the inverse Laplace transform, we get Chapter 3 256 1 t 2t 1 3t e e e . 2 2 h t Example 3.13. Transform the transfer function s 2 8s 13 H s 3s 3 7 s 2 5s 6 into a differential equation. Solution: Let H s T .F s 2 8s 13 3s 3 7 s 2 5s 6 H s Y s s 2 8s 13 X s 3s 3 7 s 2 5 s 6 3s 3 7 s 2 5s 6 Y s s 2 8s 13 X s . Take the inverse Laplace transform of both sides and ^ ^ ` ` ­ L1 s 3 Y s y ''' t ° °° L1 s 2Y s y '' t ® 1 ' ° L ^sY s ` y t ° 1 °¯ L ^Y s ` y t using ½ ° °° ¾ ° ° °¿ , we get Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Transfer Functions 3 y ''' t 7 y '' t 5 y ' t 6 y t x '' t 8 x ' t 13 x t 257 . Thus, 3 d3y t d2y t dy t 5 6y t 7 3 2 dt dt dt d 2x t dx t 8 13x t . 2 dt dt Example 3.14. Compute the impulse response and step response of the transform with the transfer function s2 s 1 s 2 2s 1 . H s Solution: We have Y s s2 s 1 s 2 2s 1 T .F H s Y s s2 s 1 X s s 2 2s 1 . X s If the input is an impulse G Thus we have Y s t , then its Laplace transform is X s 1. X s and the impulse response is simply the inverse Laplace transform of H s . Note that the degree of the numerator is the same as the degree of the denominator. As such, we have to put it in fraction form so that we can apply partial fraction expansion. Chapter 3 258 H s s2 s 1 3s 1 2 2 s 2s 1 s 2s 1 H s ª s 1 1º s2 s 1 3 3 1 3 « » 1 2 2 2 s 2s 1 s 1 s 1 «¬ s 1 »¼ . Taking the inverse Laplace transform of each term on the right, and using the linearity property of the Laplace transform, we find y t ­ s2 s 1 ½ L1 ® 2 ¾ ¯ s 2s 1 ¿ ­ 1 ½° °­ 1 °½ 1 ° L1 ^1` 3L1 ® 3 L ¾ ® 2¾ °¯ s 1 °¿ ¯° s 1 ¿° . Finally, using the transform pairs established in Table 2.1, we have y t G t 3et 3tet . Next, we compute the step response. If the input is a step function or x t u t , then X s 1 . s The step response in the Laplace transform domain is Y s H s 1 . s Its inverse Laplace transform yields the step response in the time domain. Let us carry out partial fraction expansion of Y Y s s2 s 1 s s 2 2s 1 s2 s 1 s s 1 2 . s as Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Transfer Functions It is necessary to invert Y 259 s . To accomplish this, some algebraic manipulation is necessary if we are to identify the terms on the right with the entries in Table 2.1. When expressed in terms of partial fractions, after a little manipulation, Y Y s s becomes s2 s 1 1 2 3 2 2 s s 1 s s 1 s 1 . Taking the inverse Laplace transform of each term on the right, and using the linearity property of the Laplace transform, we find y t ­ 1 ½° ­ 1 ½° ­ s 2 s 1 ½ 1 ­ 1 ½ 1 ° 1 ° L ® 2 ¾ L ® ¾ 2L ® ¾ 3L ® 2¾ ¯s¿ °¯ s 1 °¿ ¯ s 2s 1 ¿ °¯ s 1 °¿ 1 . Finally, using the transform pairs established in Table 2.1, we have y t 1 2et 3tet . 3.4 Electrical Network Transfer Functions In this section, we apply the transfer function to the mathematical modeling of electric circuits. The equivalent circuits of the electric networks that we work with initially consist of three passive linear components: resistors, capacitors, and inductors. Table 3.1 summarizes the components and the relationships between voltage and current and between voltage and charge under zero initial conditions. Chapter 3 260 Some Basic Definitions Electric Circuit: An electric circuit is a network of electrical devices whose terminals are connected together by ideal conducting wires. The three basic linear circuit elements are resistors, capacitors, and inductors. Current: The current that flows through a circuit device is the time rate of change of charge i dq , which has units of amperes (A) defined as dt coulombs/second (C/s). Voltage: The voltage across a circuit device is the work (energy) w in joules (J) required to move charge q through the device v dw , which dt has units of volts (V) defined as joules/coulomb (J/C). 3.4.1 Kirchhoff’s Current Laws G. R. Kirchhoff formulated the physical principles governing electrical circuits in 1859. They are as follows. 1. Kirchhoff’s current law: The algebraic sum of the currents flowing into any junction point must be zero. 2. Kirchhoff’s voltage law: The algebraic sum of the voltage drops around any closed loop must be zero. Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Transfer Functions 261 Table 3.1 Modeling of Electric Circuits ImpeComponent Voltage- Current-voltage Voltage-charge current dance Zs R i t v t Ri t 1 v t R v t R dq t dt R d 2q t Ls Resistor L di t v t L v t 1 i W dW C ³0 dt t i t 1 v W dW L ³0 i t C v t L dt 2 Inductor C t Capacitor dv t dt v t 1 q t C 1 Cs Vs I s Chapter 3 262 The following examples show how to use the Laplace transform method to obtain the transfer function of a linear time-invariant system (LTI) of an electrical system. Example 3.15. Determine the transfer function of the electrical system shown in Figure 3.2. R L V I = 0/p I/P = e (t) C Figure 3.2 Solution: Applying KVL to the above circuit, the integro-differential equation that characterizes the electrical system is di t t 1 ³ i W dW e t Ri t L dt C0 Here, i dq is the current. The three terms on the left give the voltage dt drop across the resistor, inductor, and capacitor, respectively. Taking the Laplace transform of the governing equation and assuming all initial conditions are zero gives Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Transfer Functions R I s L sI s 1 I s sC 1 · § ¨R L s ¸I s sC ¹ © 1 E s 1 · § ¨R L s ¸ sC ¹ . © Thus, the transfer function H H s E s E s I s T .F 263 s is I s 1 E s 1 · § ¨R L s ¸ sC ¹ © . Example 3.16. Compute the transfer function of the network shown in Figure 3.3. 3H + + u(t) ~ 1F y(t) – – Figure 3.3 Chapter 3 264 Solution: The impedance of the series connection of 3 and s is Z1 the impedance of the parallel connection of 2 and 1 s 1 2 s 2u Z2 s 2 2s 1 which is a voltage divider. Thus we have Y s Z2 s ^Z s Z s ` 1 Y s Y s U s 2 2 2s 1 2 U S 6s 9s 5 2 2 2 3s 2s 1 2 U S 6s 9s 5 2 Thus, the transfer function H T .F H s Y s U s s is 2 . 6s 9s 5 2 1 is s s 2 3s; Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Transfer Functions VL s Example 3.17. Determine the transfer function T .F V s 265 of the system shown in Figure 3.4. 1H v (t) + – + 1H vL(t) – Figure 3.4 Solution: Applying KVL to the left loop, we have L1 d d i1 t ` R1 ^i1 t i2 t ` v t ^ ^i1 t ` ^i1 t i2 t ` v t dt dt . Applying KVL to the right loop, we have R2 ^i2 t ` L2 d d i2 t ` R2 ^i2 t i1 t ` 0 i2 t ^i2 t ` ^i2 t i1 t ` 0 ^ dt dt Taking the Laplace transform of the governing equation and assuming all initial conditions are zero gives, using Chapter 3 266 ' °­ L ¬ªi t ¼º sI s °½ ® ¾ °¯ L ª¬i t º¼ I s °¿ s 1 I1 s I 2 s V s I1 s 2 s I 2 s 0 I1 s s 1 2 s 1 I2 s I2 s 1 s 2 3s 1 V s but V s VL s sI 2 s VL s s s 3s 1 2 V s Thus, the transfer function is T .F G s VL s V s s s 2 3s 1 2 s I2 s Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Transfer Functions y t of the network shown in Example 3.18. Determine the output Figure 3.5 for the input x t 267 u t . + x(t) 2H y(t) 1F – Figure 3.5 Solution: The input x t is a current source; the output y t is the voltage across the capacitor. The impedance of the inductor and capacitor are, respectively, 2s and The impedance of their parallel connection is 1 s 1 2s s 2s u 2s 2s 2 1 . Thus, the input and output of the network are related T .F H s Y s X s 2s 2s 2 1 s s2 1 2 2 1 s Chapter 3 268 s Y s 2 s 1 2 X s 2 . If we apply a step input u t Y s 1 . s 1 and U s 1 2 s2 1 2 then its output is y s ^ 2 sin 1 ` 2 t . Example 3.19. Solve the initial value problem d 2 y t dy t y t dt 2 dt x t ,y 0 0 y' 0 where x t ­ 1 0 d t d1 x t2 ® ¯1 1 t 2 x t a Determine the system transfer function H s b Determine Y s . Y s X s Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Transfer Functions 269 Solution: a Taking the Laplace transform of the governing equation and assuming all initial conditions are zero gives s2 s 1 Y s X s . Thus, H s Y s 1 s s 1 2 X s b But x t is a periodic function with period T We have X s 1 1 e sT L ª¬ x t º¼ T st ³ e x t dt 0 X s 2 ­ 1 st ½ 1 st e dt e dt ® ¾ ³1 1 e 2 s ¯ ³0 ¿ X s 1 1 e 2 s X s therefore 1 2 ­ e st ° e st ® s 1 s ° 0 ¯ 1 e s 2 s 1 e s 1 e s ½ ° ¾ ° ¿ 1 e s s 1 e s 2. Chapter 3 270 Y s 1 Y s 2 s s 1 X s X s s2 s 1 . Thus, Y s 1 e s s 1 e s s2 s 1 . Example 3.20. The output y t of a system is 2 3e t e 3t y t for an input, it is 2 4e 3t x t Determine the corresponding input for an output 2 e t te t . y1 t Solution: For the input x t X s 2 4 s s3 2 4e 3t , the Laplace transform is 6 s 1 s s3 . The corresponding output has the Laplace transform Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Transfer Functions Y s 2 3 1 s s 1 s 3 6 s s 1 s 3 271 . Hence, H s Y s 1 X s s 1 2 . Given y1 t 2 e t te t . The output has the Laplace transform Y1 s 2 1 1 s s 1 s 1 2 1 s s 1 2 Hence, the Laplace transform of the corresponding input is X1 s Y s H s 1 s . The inverse Laplace transform of X 1 x1 t u t . Example 3.21. Compute the output impulse response and x t s gives y t for an LTI system whose h t and input x t are given by h t t 2u t . u t Chapter 3 272 Solution: t 2u t , the Laplace transform is For the input x t 2 s3 . X s The corresponding impulse response h t H s has the Laplace transform 1 s Hence, Y s H s X s The output y t 2 s4 is obtained by taking the inverse Laplace transform of Y s . Thus, y t t3 u t . 3 Example 3.22. The impulse response h t by h t of an LTI system is given 1 cos t. a Determine the transfer function H s of the system. b Determine the response to the input x t G t . Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Transfer Functions 273 Solution: Given the impulse response h t and the transfer function H H s s º ª1 2 « » ¬ s s 1¼ Given the input x t we have Y Y s s of the LTI system h t 1 cos t L ª¬ h t º¼ s 1 s s2 1 . G t X s X s H s 1 1 2 s s 1 1 2 s s 1 It is now necessary to invert Y s . To accomplish this, some algebraic manipulation is necessary if we are to identify the terms on the right with the entries in Table 2.1. When expressed in terms of partial fractions, after a little manipulation, Y Y s 1 2 s s 1 s becomes A B C s si si where A, B, and C are real numbers to be determined. Chapter 3 274 A ª 1 º « 2 » «¬ s 1 »¼ s 0 1 , B ª 1 º « » «¬ s s i »¼ s i 1 2 C ª 1 º « » «¬ s s i »¼ s i 1 2 , Hence, the function Y s can be expanded as Y s 1 2 s s 1 1 1 1 1 1 2 si s 2 si Now that we have obtained the partial fraction expansion, taking the inverse Laplace transform of each term on the right and using the linearity property of the Laplace transform, we find y t ­ 1 ½ 1 ­° 1 ½° 1 1 ­° 1 ½° L1 ® ¾ L1 ® ¾ L ® ¾ ¯ s ¿ 2 ¯° s i ¿° 2 ¯° s i ¿° . Finally, using the transform pairs established in Table 2.1, we have y t 1 1 it 1 it e e 2 2 y t 1 1 it e e it 2 Thus, y t 1 cos t . Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Transfer Functions Example 3.23. The output y t 2e 3t u t when the input x t for an LTI system is found to be is u t . a Find the impulse response h t b Find the output y t of the system. when the input x t is e Solution: a For the input x t X s u t , the Laplace transform is 1 s. The corresponding output has the Laplace transform Y s 2 s3 Hence, H s Y s X s Rewriting H H s 2s s3 s as 2 s3 6 s3 2 275 6 s3 t u t . Chapter 3 276 h t the impulse response transform of H is obtained by taking inverse Laplace s . Thus, h t 2G t 6e3t u t . b For given input x t X s e t u t , the Laplace transform is 1 s 1 Thus, Y s 2s s 1 s 3 H s X s . We begin by finding the partial fraction expansion for Y s . The denominator consists of two distinct linear factors and the expansion has the form Y s 2s s 1 s 3 A B s 1 s3 where A and B are real numbers to be determined. ª 2s º A « » «¬ s 3 »¼ s 1 1 , B ª 2s º « » «¬ s 1 »¼ s 3 3 Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Transfer Functions 1 3 s 1 s3 Y s The output y t 277 . is obtained by taking the inverse Laplace transform of Y s y t e t 3e 3t u t . Example 3.24. R The RL circuit shown in Figure 3.6 with 4: and L 0.5 H . R i(t) v(t ) +– L Figure 3.6 a Determine the transfer function H s I s V s . b Find the output i t when the input v t is 12u t . Chapter 3 278 Solution: Applying KVL to this circuit, we get L di t Ri t dt v t . dq is the current. The two terms on the left give the voltage dt Here, i t drop across the inductor and resistor, respectively 0.5 di t dt 4i t v t . Taking the Laplace transform of the governing equation and assuming all initial conditions are zero gives 0.5s 4 I s V s . We define the circuit input to be the voltage and the output to be the current; hence, the transfer function is H s I s V s Now we let v t H s I s V s 1 0.5s 4 . 12u t . The transformed current is given by 1 0.5s 4 Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Transfer Functions I s 1 V s 0.5s 4 I s 12 s 0.5s 4 I s 24 s s 8 279 . We begin by finding the partial fraction expansion for I s . The denominator consists of two distinct linear factors and the expansion has the form I s 24 s s 8 A B s s 8 where A and B are real numbers to be determined. ª 24 º A « » «¬ s 8 »¼ s 0 I s 3 3 s s 8 The output 3 , B ª 24 º «¬ s »¼ s 8 . i t is obtained by taking the inverse Laplace transform of I s i t 3, 3 1 e 8t u t . Chapter 3 280 3.5 Mechanical System Transfer Functions In this section, we formally apply the transfer function to the mathematical modeling of a translational mechanical system. Automated systems, like electrical networks, have three passive linear components. Two of them— the spring and the mass—are energy-storage elements; one of them—the viscous damper—dissipates energy. Let us take a look at these mechanical elements, which are shown in Table 3.2. In the table, K, D, and M are termed spring constant, coefficient of viscous friction, and mass, respectively. Table 3.2 Modeling of Mechanical Elements Impedance Component Force- Force- displacement velocity K Z s t F t F t Kx t F t D K ³ v W dW 0 K Dv t Ds Spring D Damper dx t dt F t F s X s Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Transfer Functions 281 Mass F t M M d 2x t dt F t 2 M dv t M s2 dt The following examples show how to use the Laplace transform method to obtain the transfer function of a linear time-invariant system (LTI) of a mechanical system. Example 3.25. The suspension system of an automobile is shown in Figure 3.7. a Find a differential equation to describe the system. b Determine the transfer function X s F s . Displacement X K Force F M D Figure 3.7 Chapter 3 282 Solution: a The model consists of a block with mass M, which denotes the weight of the automobile. When the automobile hits a pothole, a vertical force F t is applied to the mass and causes the automobile to oscillate. The suspension system consists of a spring with a spring constant K and a dashpot, which represents the shock absorber D. The spring generates force Kx t where x t is the vertical displacement measured from equilibrium. The dashpot is modeled to generate viscous friction as D dx dt The differential equation to describe the system is M d 2x t b dt 2 D dx t dt K x t F t Taking the Laplace transform of the governing equation and assuming all initial conditions are zero gives M s 2 X s D sX s K X s M s2 D s K X s X s F s 1 M s D sK F s 2 Thus, the transfer function H . s is F s Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Transfer Functions T .F H s X s F s 283 1 . M s D sK 2 Example 3.26. Determine the transfer function T .F X2 s F s of the translational mechanical system shown in Figure 3.8. x1(t) x2(t) 1N/m f(t) 0.1kg 1 N-s/m 0.1kg Frictionless Figure 3.8 Solution: Applying Newton’s law to the node x1 t d2 d M 1 2 ^ x1 t ` k x1 t x2 t D ^ x1 t x2 t ` F t dt dt 0.1 d2 d x t ` x1 t x2 t ^ x1 t x2 t ` F t 2^ 1 dt dt Chapter 3 284 d2 d x t ` 10 x1 t x2 t 10 ^ x1 t x2 t ` 10 F t 2^ 1 dt dt . Applying Newton’s law to the node x2 t M2 d2 d x t ` k x2 t x1 t D ^ x2 t x1 t ` 0 2^ 2 dt dt d2 d 0.1 2 ^ x2 t ` x2 t x1 t ^ x2 t x1 t ` 0 dt dt d2 d x t ` 10 x2 t x1 t 10 ^ x2 t x1 t ` 0 2^ 2 dt dt . Taking the Laplace transform of the governing equations and assuming all initial conditions are zero gives ­ L ª x ''1 t º s 2 X 1 s ½ ¼ ° ¬ ° ° ° ' ® L ¬ª x 1 t ¼º sX 1 s ¾ ° ° °¯ L ª¬ x1 t º¼ X 1 s °¿ using s 2 10s 10 X 1 s 10 s 1 X 2 s 10 F s 10 s 1 X 1 s s 2 10s 10 X 2 s 0 Solving X 2 s using Cramer’s rule Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Transfer Functions ' s 2 10 s 10 10 s 1 10 s 1 s 2 10s 10 '2 X2 s T .F s 2 10 s 10 10 F s 10 s 1 0 ª s 2 10 s 10 2 100 s 1 2 º ¬« ¼» 100 s 1 F s '2 ' 100 s 1 F s X2 s 100 s 1 F s 100 s 1 F s ' F s ª s 2 10s 10 2 100 s 1 2 º «¬ »¼ ' . Thus, the transfer function T .F is T .F 285 X2 s 100 s 1 F s ª s 2 10 s 10 2 100 s 1 2 º ¬« ¼» . 286 Chapter 3 Example 3.26. Determine the transfer function T .F X2 s F s of the translational mechanical system shown in Figure 3.9. Figure 3.9 Solution: Applying Newton’s law to the node x1 t d2 d d M 1 2 ^ x1 t ` kx1 t D1 ^ x1 t ` D3 ^ x1 t x2 t ` F t dt dt dt . Applying Newton’s law to the node x2 t d2 d d d M 2 2 ^ x2 t ` D2 ^ x2 t ` D4 ^ x2 t ` D3 ^ x2 t x1 t ` 0 dt dt dt dt Taking the Laplace transform of the governing equations and assuming all initial conditions are zero gives Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Transfer Functions 287 ­ L ª x ''1 t º s 2 X 1 s ½ ¼ ° ¬ ° ° ° ' ® L ¬ª x 1 t ¼º sX 1 s ¾ ° ° °¯ L ª¬ x1 t º¼ X 1 s °¿ using M 1s 2 D1 D3 s k X 1 s D3 sX 2 s ^ F s ` D3 sX 1 s M 2 s 2 D2 D3 D4 s X 2 s Solving X 2 ' ' ª ¬ s using Cramer’s rule M 1s 2 D1 D3 s k D3 s D3 s ^M s D D D s` 2 2 2 T .F Thus, 3 4 '2 ' X2 s F s 2 2 1 1 3 2 2 X2 s 2 ^ M s D D s k u M s D D D s` D s º¼ D3 s F s M 2 s D2 D3 D4 s 0 '2 0 2 3 4 3 ^M s D D D s` F s 2 2 2 3 4 ^M s D D D s` F s 2 2 2 3 4 ' ^M s D D D s` F s ^M s D D D s` 2 2 2 2 3 ' F s 4 2 2 ' 3 4 Chapter 3 288 T .F ^M s D D D s` . 2 X2 s 2 2 3 4 ' F s Example 3.27. Use the Laplace transform to find the transfer function and impulse response of the system if the differential equation describes the system d 2z t dt 2 3 dz t dt d 2x t 2z t dt 2 6 dx t dt 7x t . Solution: Taking the Laplace transform of the governing equation and assuming all initial conditions are zero gives ^ ` ^ ` ^ ` ^ ` L z '' t 3L z ' t 2 L ^ z t ` L x '' t 6 L x ' t 7 L ^ x t ` using, we get '' 2 2 ­ ° L ª¬ z t ¼º s L ª¬ z t º¼ s Z s ® ' °¯ L ª¬ z t º¼ sL ª¬ z t º¼ sZ s s 2 3s 2 Z s T .F H s H s 1 ½ ° ¾ °¿ s 2 6s 7 X s Z s s 2 6s 7 X s s 2 3s 2 3s 5 s 1 s 2 1 A B s 1 s2 . Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Transfer Functions We begin by finding the partial fraction expansion for 289 H s , the denominator consists of two distinct linear factors and so the expansion has the form 3s 5 s 1 s 2 A B s 1 s2 where A and B are real numbers to be determined. ª 3s 5 º 2 , B A « » ¬« s 2 ¼» s 1 H s 1 2 1 s 1 s2 ª 3s 5 º 1 « » ¬« s 1 ¼» s 2 . Taking the inverse Laplace transform, we get h t G t 2et e2t . Example 3.28. Use the Laplace transform to find the transfer function and the impulse response of the system if the differential equation describes the system d 2z t dt 2 4 dz t dt 10 z t x t . Solution: Taking the Laplace transform of the governing equation and assuming all initial conditions are zero gives Chapter 3 290 ^ ` ^ ` L z '' t 4 L z ' t 10 L ^ z t ` L ^ x t ` '' 2 2 ­ ° L ¬ª z t ¼º s L ª¬ z t º¼ s Z s ® ' °¯ L ¬ª z t ¼º sL ¬ª z t ¼º sZ s using s 2 4s 10 Z s T .F H s X s Z s H s ½ ° ¾ °¿ , we get X s 1 s 4 s 10 2 1 2 s2 6 . Taking the inverse Laplace transform, we get h t 1 2t e sin 6 6t . Summary In this chapter, we have described and explained the concept of the transfer function. x We have developed the input-output relationship by defining the transfer function. The Laplace transform of the impulse response of the system is called the transfer function of the system in the s domain. The Laplace transform converts a time-domain differential equation into a simple algebraic equation in the frequency domain. Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Transfer Functions 291 Several simple examples have been solved to illustrate the relevant concepts. x LTI systems governed by differential equations have been analyzed by finding the transfer function under the assumption of zero initial conditions. This is useful for developing the input-output relationship. The transfer function of electrical and mechanical systems have also been explained with several examples. CHAPTER 4 THE APPLICATION OF THE LAPLACE TRANSFORM TO LTI DIFFERENTIAL SYSTEMS: SOLVING IVPS 4.1 Introduction This chapter aims to show how Laplace transforms can be used to solve initial value problems for linear differential equations i. The advantages of the transform method for linear differential equations are listed below. (i) If we compare the transform method with the classical method to solve ordinary linear differential equations with constant coefficients using homogeneous and particular solutions, the Laplace transform has the advantage. The Laplace transform takes the initial conditions into account in the calculation, which reduces the amount of calculation considerably, especially for higher-order differential equations. (ii) Other important advantages of the transform method are worth noting. For example, the technique can easily handle equations involving forcing functions having jump discontinuities (unit step and impulse functions). i The Laplace transform was first introduced by Pierre Laplace in 1779 in his research on probability. G. Doetsch helped develop the use of Laplace transforms in solving differential equations. His work in the 1930s served to justify the operational calculus procedures earlier used by Oliver Heaviside. Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Solving IVPS 293 (iii) Further, the method can be used to solve certain other types of equation, such as linear differential equations with variable coefficients, integro-differential equations, systems of differential equations, and partial differential equations. In Section 4.2, we will show the scheme by which the Laplace transform can equally be applied to the initial value problem. An evaluation of the total response (natural and forced) of the LTI system by the Laplace transform method is presented in Section 4.3. Even more general are the systems of several coupled ordinary linear differential equations with constant coefficients in Section 4.4. Again, these systems can be solved by applying the same method, although, in the s domain, we have a system of several equations. For convenience, we restrict ourselves to systems of only two differential equations. LEARNING OBJECTIVES On reaching the end of this chapter, we expect you to have understood and be able to apply: x The Laplace transform method to solve initial value problems. x How the impulse and step response of the LTI system is described by an ordinary linear differential equation with constant coefficients. x The use of the Laplace transform to find the total response of the LTI system. x The use of the Laplace transform to solve coupled ordinary linear differential equations with constant coefficients and under initial conditions. Chapter 4 294 4.2 The Scheme for Solving IVPs The Laplace transform technique for solving nth-order ordinary linear differential equations with constant coefficients (homogeneous or nonhomogeneous) is a three-step process. First, linear differential equations with constant coefficients are transformed by the Laplace transform into an algebraic equation in s and L ^ f t ` F s the Laplace transform of the solution of the initial value problem. Next, the unknown quantity in the algebraic equation F s is solved by algebraic manipulation. Finally, the inverse Laplace transform is applied to the equation to derive the solution of the initial value problem. The scheme for solving a linear differential equation is outlined below. Step 1: Consider the Laplace transform on both sides of the equation. Step 2: Use the properties of the Laplace transform and the initial conditions, simplify the algebraic equation obtained for Y s in the S domain. Step 3: Find the inverse transform of Y s to obtain y t , the solution of the differential equation. 4.2.1 Definitions: Homogeneous and Non-homogeneous Linear Differential Equations An nth-order ordinary differential equation of the form is aN t dN y t d N 1 y t d2y t dy t a t a t ...... a1 t a0 t y t N 1 2 N N 1 2 dt dt dt dt f t Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Solving IVPS 295 aN t , aN 1 t .........a1 t and a0 t , which are all functions of the independent variable t alone. If f t 0, then the above linear differential equation is said to be homogeneous. If f t z 0 , then the above linear differential equation is said to be non- homogeneous. The following example shows how to use the Laplace transform method to obtain a general solution for a linear differential equation with constant coefficients. Example 4.1. Determine the solution of the initial value problem dy t 4y t dt et with y 0 2. Solution: Let y ' t 4y t et . Because of the linearity of the equation and the Laplace transform operation, taking the Laplace transform of the differential equation, we have L ª¬ y ' t º¼ 4 L ª¬ y t º¼ L ª¬et º¼ 1 ª sL ª¬ y t º¼ y 0 º 4 L ª¬ y t º¼ ¬ ¼ s 1 . Chapter 4 296 Substituting the given initial conditions into the above equation, and solving the resulting equation for L ª¬ y t º¼ 2s 1 s 1 s 4 L ^ y t ` , we find . It is now necessary to invert Y s L ^ y t ` and to accomplish this some algebraic manipulation is necessary if we are to identify the terms on the right with the entries in Table 2.1. When expressed in terms of partial fractions, after a little manipulation, Y Y s 2s 1 s 1 s 4 s becomes A B s 1 s 4 where A and B are real numbers to be determined. ª 2s 1 º A « » «¬ s 4 »¼ s 1 1 , B 5 Hence, the given function Y Y s 2s 1 s 1 s 4 ª 2s 1 º « » «¬ s 1 »¼ s 4 9 5 . s can be expanded as 1 1 9 1 5 s 1 5 s 4 Now that we have obtained the partial fraction expansion. Taking the inverse Laplace transform of each term on the right and using the linearity property of the Laplace transform, we find Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Solving IVPS 1 1 ­ 1 ½ 9 1 ­° 1 ½° L ® ¾ L ® ¾ 5 ¯ s 1 ¿ 5 ¯° s 4 ¿° y t 297 . Finally, using the transform pairs established in Table 2.1, we have 1 t 9 4t e e . 5 5 y t As a quick check of your computational correctness, it is recommended that you verify if the computed solution meets the given initial conditions. This example illustrates a fundamental difference between the solutions of initial value problems obtained using the Laplace transform and using the classical approach (finding complementary functions and a particular integral). In the classical approach, when solving an initial value problem, first a general solution is found and then the arbitrary constants are matched to the initial conditions. However, in the Laplace transform approach, the initial conditions are incorporated when the equation is transformed and the inversion of Y s gives the required solution of the initial value problem immediately. Example 4.2. Obtain the solution of the differential equation d2y t dt 2 2 dy t dt 4y t sin 2t along with the initial conditions y 0 0 y' 0 . Chapter 4 298 Solution: Assuming that Laplace transform of the solution Y s exists and using the fact that L is a linear operator, we take the Laplace transform of the above differential equation and write ­° d 2 y t ½° dy t L® 2 4 y t ¾ L ^sin 2t` 2 dt °¯ dt °¿ L ª¬ y '' t º¼ 2 L ª¬ y ' t º¼ 4 L ¬ª y t ¼º 2 s 4 2 ª¬ s 2Y s sy 0 y ' 0 º¼ 2 ª¬ sY s y 0 º¼ 4Y s It is now necessary to invert Y 2 s2 4 . s . To accomplish this, some algebraic manipulation is necessary if we are to identify the terms on the right with the entries in Table 2.1. When expressed in terms of partial fractions, after a little manipulation, Y Y s s becomes 2 s 2s 4 s 2 4 2 . Using partial fractions, we can write this as Y s 2 s 2s 4 s 2 4 2 As B Cs D 2 s 2s 4 s 4 2 where A, B, C, and D are real numbers to be determined. Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Solving IVPS 2 As B s 2 4 Cs D s 2 2 s 4 299 . Hence, comparing the coefficients of both sides gives s3 : A C 0, s2 : D B 0, s: 2 D 4C 0, 1: 4B 4D 2. Using these equations, we obtain A 1 ,B 2 1 ,C 4 1 and D 4 0. Hence, we have Y s 1 2 s 1 4 2 s 2s 4 14 s s2 4 Y s 1 °­ 1 s 1 °½ 1 °­ °½ 1 °­ s °½ ® 2 ¾ ® 2 ¾ ® ¾ 4 ° s 2s 4 ° 4 ° s 2s 4 ° 4 ° s 2 4 ° ¯ ¿ ¯ ¿ ¯ ¿ Y s ­ ½ 1° 1 1 ­° s ½° ° 1 ­° s 1 ½° ® ¾ ® ¾ ® ¾ 4 ° s 1 2 3 ° 4 ° s 1 2 3° 4 ° s2 4 ° ¯ ¿ ¯ ¿ ¯ ¿ . Applying the inverse Laplace transform to the above equation, and using its linearity, we get Chapter 4 300 1 y t 4 3 e t sin 1 3 t e t cos 4 1 3 t cos 2t . 4 The following example illustrates how to use the Laplace transform method to obtain the general solution of second-order linear homogeneous differential equations with constant coefficients. Example 4.3. Obtain the Solution of differential equations d3y t dt 2 2 d2y t dt 2 dy t dt 2y t 0 along with the initial conditions y 0 0 y ' 0 & y '' 0 6. Solution: Assuming that Laplace transform of the solution Y s exists, and using the fact that L is a linear operator, we take the Laplace transform of the above differential equation and write 3 d 2 y t dy t °­ d y t °½ L® 2 2 y t ¾ L ^0` 2 2 dt dt °¯ dt °¿ L ª¬ y ''' t º¼ 2 L ª¬ y '' t º¼ L ª¬ y ' t º¼ 2 L ª¬ y t º¼ 0 3 2 ' '' 2 ' °­ ¬ª s Y s s y 0 sy 0 y 0 ¼º 2 ¬ª s Y s sy 0 y 0 ¼º °½ ® ¾ 0 ª¬ sY s y 0 º¼ 2Y s °¯ °¿ . Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Solving IVPS It is now necessary to invert Y 301 s . To accomplish this, some algebraic manipulation is necessary if we are to identify the terms on the right with the entries in Table 2.1. When expressed in terms of partial fractions, after a little manipulation, Y Y s Y s s becomes 6 s3 2s 2 s 2 6 3 2 s 2s s 2 6 s 1 s 1 s 2 A B C s 1 s 1 s2 where A, B, and C are real numbers to be determined. ª º ª º ª º 6 6 6 1, B « 2. A « 3, C « » » » «¬ s 1 s 2 ¼» s 1 ¬« s 1 s 2 ¼» s 1 ¬« s 1 s 1 ¼» s 2 Y s 1 3 2 s 1 s 1 s2 . Applying the inverse Laplace transform to the above equation, and using the linearity of the inverse Laplace transform, gives us y t et 3et 2e2t . The following examples illustrate how to use the Laplace transform method to obtain the general solution of first and second-order linear nonhomogeneous differential equations with constant coefficients. Chapter 4 302 Example 4.4. Use Laplace transform techniques to find the solution to the first-order differential equation dy t dt 3y t e 2t with y 0 1. Solution: Because of the linearity of the equation and the Laplace transform operation, taking the Laplace transform of the differential equation, we have ­ dy t ½ L® 3 y t ¾ L e 2t ¯ dt ¿ ^ ` . Using the derivative property and assuming all initial conditions are zero gives ^sY s y 0 ` 3Y s 1 s2 . With the initial value of y 0 , this equation can be written as Y s 1 1 s3 s3 s2 . We expand this S domain solution into partial fractions as Y s 1 1ª 4 1 º « » s 3 5 ¬« s 3 s 2 ¼» . Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Solving IVPS 303 Applying the inverse Laplace transform to the above equation, and using its linearity, we get e 3t y t 4 3t 1 2t e e 5 5 which is the required general solution of the given linear differential equation. Example 4.5. Solve the differential equation d2y t dt 2 y t 1 with y 0 0 y' 0 . Solution: Let y '' t y t 1 Because of the linearity of the equation and of the Laplace transform operation, taking the Laplace transform of the differential equation, we have L ª¬ y ''' t º¼ L ª¬ y t º¼ L >1@ 1 ª s 2 L ª¬ y t º¼ sy 0 y ' 0 º L ª¬ y t º¼ ¬ ¼ s It is now necessary to invert L ^ y t ` . To accomplish this, some algebraic manipulation is necessary if we are to identify the terms on the right with the entries in Table 2.1. When expressed in terms of partial fractions, after a little manipulation, L ^ y t ` becomes Chapter 4 304 L ª¬ y t º¼ L ª¬ y t º¼ 1 s s2 1 A Bs C s s2 1 s 1 2 . s s 1 Applying the inverse Laplace transform to the above equation, and using the linearity of the inverse Laplace transform, give us the results in which we can write the time-domain solution y t as 1 cos t. y t Example 4.6. Obtain the solution of the second-order differential equation d2y t dy t 6y t et with the initial conditions y 0 dt 2 5 dt 2 and y ' 0 1. Solution: Assuming that Laplace transform of the solution Y s exists, and using the fact that L is a linear operator, we take the Laplace transform of the above differential equation and write 2 dy t °­ d y t L® 5 6y t 2 dt °¯ dt °½ t ¾ L e °¿ ^ ` Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Solving IVPS L ª¬ y '' t º¼ 5L ª¬ y ' t º¼ 6 L ª¬ y t º¼ s 2 5s 6 Y s 1 2 s 11 s 1 s 2 5s 6 Y s 2s 2 13s 12 s 1 Y s 2 s 2 13s 12 s 1 s 2 s 3 305 1 s 1 . We begin by finding the partial fraction expansion for Y s . The denominator consists of three distinct linear factors and so the expansion has the form Y s 2 s 2 13s 12 s 1 s 2 s 3 A B C s 1 s2 s3 where A, B, and C are real numbers to be determined. ª 2 s 2 13s 12 º A « » «¬ s 2 s 3 »¼ s 1 1 , 2 ª 2 s 2 13s 12 º « » «¬ s 1 s 3 »¼ s 3 9 , 2 C hence, the function Y B ª 2 s 2 13s 12 º « » «¬ s 1 s 3 »¼ s 2 s can be expanded as 6, Chapter 4 306 2 s 2 13s 12 s 1 s 2 s 3 Y s 1 1 6 9 1 2 s 1 s2 2 s3 . Now that we have obtained the partial fraction expansion, taking the inverse Laplace transform of each term on the right and using the linearity property of the Laplace transform, we find that y t ­ 1 ½° 9 1 ­° 1 ½° 1 1 ­° 1 ½° 1 ° L ® ¾ 6L ® ¾ L ® ¾ 2 ¯° s 1 ¿° ¯° s 2 ¿° 2 ¯° s 3 ¿° . Finally, using the transform pairs established in Table 2.1, we have y t 1 t 9 e 6e 2t e 3t . 2 2 Some of the most useful and interesting applications of the Laplace transform method are found in the solution of linear differential equations with impulsive non-homogeneous functions. Equations of this type frequently arise in the analysis of the flow of current in electric circuits or the vibrations of mechanical systems, where voltages or forces of large magnitude act over very short time intervals. We will now discuss some discontinuous non-homogeneous functions as illustrations. Example 4.7. Solve the initial value problem d2y t dy t 5 6y t 2 dt dt with y 0 0 y' 0 . G t S G t 2S Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Solving IVPS 307 Solution: In this instance, the forcing function is the step function ^u t S u t 2S ` of the above equation. This function is discontinuous at t S and t 2S . Therefore, it is not the solution of any linear homogeneous differential equation with constant coefficients. This is an example of an initial value problem that we cannot solve easily using the method of undetermined coefficients. The advantage of the Laplace transform method is that the solution of the above initial value problem can be obtained with one application of the given method y '' t 5 y ' t 6 y t G t S G t 2S . Because of the linearity of the equation and of the Laplace transform operation, taking the Laplace transform of the differential equation, we have L ¬ª y '' t ¼º 5 L ¬ª y ' t ¼º 6 L ª¬ y t º¼ L ^ G t S G t 2S ` ­ L ª y '' t º s 2 L ª¬ y t º¼ sy 0 y ' 0 ½ ° ¬ ¼ ° ® ¾ ' °¯ L ¬ª y t ¼º sL ¬ª y t ¼º y 0 °¿ ^¬ªs L ¬ª y t ¼º sy 0 y 0 ¼º 5 ¬ªsL ª¬ y t º¼ y 0 ¼º 6L ª¬ y t º¼ ` e e 2 S s ' . This algebraic equation can be solved for L ^ y t ` as 2S s Chapter 4 308 L ª¬ y t º¼ e S s e 2S s 1 s2 s3 It is now necessary to invert . L ^ y t ` . To accomplish this, some algebraic manipulation is necessary if we are to identify the terms on the right with the entries in Table 2.1. When expressed in terms of partial fractions, after a little manipulation, L ^ y t ` becomes L ª¬ y t º¼ ª 1 1 º e S s e 2S s « » s 3 »¼ «¬ s 2 L ª¬ y t º¼ e S s e S s e2S s e2S s s2 s3 s2 s3 . Applying the inverse Laplace transform to the above equation, and using the linearity of the inverse Laplace transform, we can write the timedomain solution y t as y t e 2 t S e 3 t S u t S e 2 t 2S e 3 t 2S u t 2S . Example 4.8. A mass attached to a vertical spring undergoes forced vibration so that the motion is described by the second-order differential equation d2y t dt 2 with 4y t y 0 sin 2t 10 and y ' 0 0. Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Solving IVPS 309 y t is the displacement at time t. Use the Laplace transform to determine the removal at time t. Solution: Because of the linearity of the equation and of the Laplace transform operation, taking the Laplace transform of the differential equation, we have 2 °­ d y t 4y t L® 2 °¯ dt °½ ¾ L ^ sin 2t` °¿ . Using the derivative property and assuming all initial conditions are zero gives ^s Y s sy 0 y 0 ` 4Y s 2 ' With the initial values of y 0 and this expression for Y Y s 2 s 4 2 y ' 0 in this equation and solving s yields two rational function components 10 s 2 2 s 4 s2 4 2 . Taking inverse the Laplace transform and applying the convolution theorem to the second term on the right-hand side, we get y t 1 1 10 cos 2t sin 2t t cos 2t . 8 4 Chapter 4 310 Example 4.9. Determine the solution of the initial value problem d2y t dt 2 4y t F t with y 0 y' 0 0 where F t is the periodic function F t ­1 0 t 1 with F t 2 ® ¯0 1 t 2 F t . Solution: Given that d2y t 4y t dt 2 F t . Because of the linearity of the equation and of the Laplace transform operation, taking the Laplace transform of the differential equation, we have L ª¬ y ''' t º¼ 4 L ª¬ y t º¼ L ª¬ F t º¼ T s 2 4 L ª¬ y t º¼ 1 e st F t dt 1 e st ³0 1 s 2 4 L ª¬ y t º¼ 1 e st dt 2 s ³ 1 e 0 . Thus, L ª¬ y t º¼ 1 s 1 e s s 2 4 1 s 1 e 2 s 1 e s 1 s 1 e s Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Solving IVPS 311 Partial fractions give 1 ª1 s º « 2 » 4 «s s 4 » ¬ ¼. 1 2 s s 4 1 1 e s can be interpreted as the sum of a geometric series with a s common ratio e , so we may write 1 1 e s 1 e s e 2 s e 3 s e 4 s ........ In other words, L L ª¬ y t º¼ ^ y t ` can be expressed as an infinite series 1 ª1 s º « 2 » 1 e s e 2 s e 3s e 4 s ........ 4 «s s 4 » ¬ ¼ . Applying the inverse Laplace transform to the above equation, and using the linearity of the inverse Laplace transform, results in y t 1 1 1 >1 cos 2t @ ª¬1 cos 2 t 1 º¼ u t 1 ª¬1 cos 2 t 2 º¼ u t 2 ............... 4 4 4 Example 4.10. Use Laplace transform techniques to find the solution to the second-order differential equation d2y t dt 2 9y t cos 2t with y 0 1 & y' 0 0. Chapter 4 312 Solution: Let d2y t dt 2 9y t cos 2t . Because of the linearity of the equation and of the Laplace transform operation, taking the Laplace transform of the differential equation, we have L ª¬ y ''' t º¼ 9 L ª¬ y t º¼ L ª¬cos 2t º¼ ­ L ¬ª y '' t ¼º s 2 L ª¬ y t º¼ sy 0 y ' 0 ½° ° ® ¾ ' °¯ L ª¬ y t º¼ sL ª¬ y t º¼ y 0 °¿ using , we get s ª s 2 L ª¬ y t º¼ sy 0 y ' 0 º 9 L ª¬ y t º¼ 2 ¬ ¼ s 4 . This algebraic equation can be solved for L L ¬ª y t ¼º s 2 2 s 4 s 9 1 s 9 ^ y t ` as 2 . Taking the inverse Laplace transform of each term on the right, and using the linearity property of the Laplace transform, we find that y t ­° ½° ­ 1 ½° s 1° L ® 2 ¾ L ® 2 ¾ 2 °¯ s 4 s 9 °¿ °¯ s 9 °¿ . 1 Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Solving IVPS 313 This solution is in the form of the product of two known Laplace transforms. Thus we invert using either partial fractions or the convolution theorem. Using the convolution theorem yields ª º s » L1 « 2 «¬ s 4 s 2 9 »¼ 1 ^cos 2t cos 3t ` 5 (see Chapter 2, Example 2.26 ). Thus, 1 1 cos 2t cos 3t ` sin 3t . ^ 5 5 y t Example 4.11. Solve the differential equation d2y t dt 2 3 dy t dt 2y t 10u t subject to the initial conditions y 0 1 and y ' 0 2. Solution: In this instance, the forcing function is the step function u t above equation. This function is discontinuous at t of the 0 . Therefore, it cannot offer a solution to any linear homogeneous differential equation with constant coefficients. This is an example of an initial value problem that we cannot solve quickly using the method of undetermined coefficients. The advantage of the Laplace transform method is that the Chapter 4 314 solution of above the initial value problem can be obtained with one application of the method, given that y '' t 3 y ' t 2 y t 10u t . Because of the linearity of the equation and the Laplace transform operation, taking the Laplace transform of the differential equation, we have L ª¬ y '' t º¼ 3L ª¬ y ' t º¼ 2 L ª¬ y t º¼ 10 L ^u t ` ­ L ª y '' t º s 2 L ª¬ y t º¼ sy 0 y ' 0 ½ ° ¬ ¼ ° ® ¾ ' °¯ L ª¬ y t º¼ sL ª¬ y t º¼ y 0 °¿ using , we get ^ª¬s L ª¬ y t º¼ sy 0 y 0 º¼ 3 ª¬sL ª¬ y t º¼ y 0 º¼ 2L ª¬ y t º¼ ` 10s 2 ' . This algebraic equation can be solved for L s 2 s 10 L ª¬ y t º¼ s s 1 s 2 ^ y t ` as . It is now necessary to invert L ^ y t ` . To accomplish this, some algebraic manipulation is necessary if we are to identify the terms on the right with the entries in Table 2.1. When expressed in terms of partial fractions, after a little manipulation, L ^ y t ` becomes Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Solving IVPS L ª¬ y t º¼ s 2 s 10 s s 1 s 2 A B C s s 1 s2 ª s 2 s 10 º ª s 2 s 10 º A « 5, B 10, C » « » «¬ s 1 s 2 »¼ s 0 «¬ s s 2 »¼ s 1 L ª¬ y t º¼ 315 ª s 2 s 10 º 6. « » «¬ s s 1 »¼ s 2 5 10 6 . s s 1 s2 Applying the inverse Laplace transform to the above equation, and using its linearity, we get 5 10et 6e2t . y t The above equation is the required general solution of the given linear differential equation. Example 4.12. Use the Laplace transform to find the output response of the system described by the second-order differential equation d2y t dt 2 3 with y 0 dy t dt 2y t u t S 0 y' 0 . Solution: In this instance, the forcing function is the step function u t S above equation. This function is discontinuous at t of the S and, therefore, is not the solution of any linear homogeneous differential equation with constant coefficients. This is an example of an initial value problem that Chapter 4 316 we cannot solve easily using the method of undetermined coefficients. The advantage of the Laplace transform method is that the solution of the above initial value problem can be obtained with one application. Given that d2y t dt 2 3 dy t dt 2y t u t S . Because of the linearity of the equation and of the Laplace transform operation, taking the Laplace transform of the differential equation, we have ­° d 2 y t dy t L® 3 2y t 2 dt dt ¯° ½° ¾ L^ u t S ` ¿° . Using the derivative property and assuming all initial conditions are zero gives ^s 3s 2 `Y s 2 e S s s . It is now necessary to invert Y s . To accomplish this, some algebraic manipulation is necessary if we are to identify the terms on the right with the entries in Table 2.1. When expressed in terms of partial fractions, after a little manipulation, Y Y s e S s s s 2 3s 2 s becomes e S s s s 1 s 2 Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Solving IVPS Y s eS s s s2 3s 2 Y s eS s 317 eS s s s 1 s 2 1 s s 1 s 2 ­° A B C ½° eS s ® ¾ s2 s 3 ¿° ¯° s where A, B, and C are real numbers to be determined. ª º 1 A « » «¬ s 1 s 2 »¼s 0 Y s ª º 1 1 , B « 1, C » 2 «¬ s s 2 »¼s 1 ª 6 º 1 . « » «¬ s s 1 »¼s 2 2 ­° 1 1 1 1 1 ½° eS s ® ¾ ¯° 2 s s 1 2 s 2 ¿° . Applying the inverse Laplace transform to the above equation, and using its linearity, results in y t § 1 t S 1 2 t S · e ¨ e ¸ u t S 2 ©2 ¹ . The above equation is the required general solution of the given linear differential equation. The next example is a differential equation of an unusual type because the function y t occurs, not only as the dependent variable in the differential equation, but also inside the convolution integral that forms the nonhomogeneous term. Equations of this type, involving both the integral of an unknown function and its derivative, are called integro-differential equations. Chapter 4 318 Example 4.13. Solve the integro-differential equations d2y t dt 2 t ³ f u sin t u du with y 0 y t 1& y ' 0 0. 0 Solution: Given that t y '' t y t ³ f u sin t u du 0 Because of the linearity of the equation and of the Laplace transform operation, taking the Laplace transform of the differential equation we have t °­ °½ L ª¬ y t º¼ L ª¬ y t º¼ L ® ³ f u sin t u du ¾ ¯° 0 ¿° '' using '' 2 ' °­ L ª¬ y t º¼ s L ª¬ y t º¼ sy 0 y 0 °½ ® ¾ ¯° and convolution theorem ¿° ^ª¬s L ª¬ y t º¼ sy 0 y 0 º¼ L ª¬ y t º¼ ` 2 ' This algebraic equation can be solved for L L ª¬ y t º¼ , we get L ª¬ y t º¼ s2 1 ^ y t ` as 2 s2 1 s2 s 1 . We expand this S domain solution into partial fractions as . Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Solving IVPS L ª¬ y t º¼ 2 s2 1 2 s s 1 4 2 2 2 s 1 s s . Thus, we can write the time-domain solution y t as 4et 2 2t. y t The above equation is the required general solution of the given linear differential equation. Example 4.14. Determine the solution of the initial value problem d2y t dt 2 4 dy t dt 4y t e2t t 2 with y 0 0 & y' 0 0. Solution: The solution process is the same as in example 1. Taking the Laplace transform of the given differential equation and imposing the initial conditions, we find, successively ­° d 2 y t ½° d2y t 2 t 2 L® y t 4 4 ¾ L e t 2 2 dt ¯° dt ¿° . ^ ` Because of the linearity of the equation and the Laplace transform operation, taking the Laplace transform of the differential equation, we have ^ L ª¬ y '' t º¼ 4 L ª¬ y ' t º¼ 4 L ª¬ y t º¼ L e 2t t 2 ` 319 Chapter 4 320 ­ L ª y '' t º s 2 L ª¬ y t º¼ sy 0 y ' 0 ½ ° ¬ ¼ ° ® ¾ ' °¯ L ª¬ y t º¼ sL ª¬ y t º¼ y 0 °¿ using , we get ^ª¬s L ª¬ y t º¼ sy 0 y 0 º¼ 4 ª¬sL ª¬ y t º¼ y 0 º¼ 4L ª¬ y t º¼ ` s 22 2 ' This algebraic equation can be solved for L L ª¬ y t º¼ ^ y t ` as 2 s2 5 . Thus we can write the time-domain solution y t as 2e2t t 4 24 y t e2t t 4 . 12 The above equation is the required general solution of the given linear differential equation. Example 4.15. Obtain the solution of the differential equations d2y t dt 2 5 dy t dt 6y t 2e t along with the initial conditions y 0 1 and y ' 0 0. 3 Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Solving IVPS 321 Solution: Assuming that the Laplace transform of the solution Y s exists and using the fact that L is a linear operator, we take the Laplace transform of the above differential equation and write ­° d 2 y t ½° dy t t L® y t 5 6 ¾ 2L e 2 dt ¯° dt ¿° ^ ` L ¬ª y '' t ¼º 5L ¬ª y ' t ¼º 6 L ¬ª y t ¼º 2 s 1 2 s 1 . ª¬ s 2Y s sy 0 y ' 0 º¼ 5 ª¬ sY s y 0 º¼ 6Y s Imposing the initial conditions, we obtain the Laplace transform of the solution s 2 5s 6 Y s 2 s 5. s 1 Solving this expression for Y s yields two rational function components Y s 2 s5 s 1 s 2 s 3 s 1 s 2 s 3 . Chapter 4 322 We begin by finding the partial fraction expansion for Y s . The denominator consists of three distinct linear factors and so the expansion has the form Y s s7 s 1 s 2 s 3 A B C s 1 s2 s3 where A, B, and C are real numbers to be determined. ª º s7 A « » ¬« s 2 s 3 ¼» s 1 C ª º s7 « » «¬ s 1 s 2 »¼ s 3 ª º s7 3 , B « » ¬« s 1 s 3 ¼» s 2 5, 2, Y s 3 5 2 s 1 s2 s3 y t 3et 5e2t 2e3t . The above equation is the required general solution of the given linear differential equation. Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Solving IVPS 323 Example 4.16. Use the Laplace transform to find the output response of the system described by the second-order differential equation d2y t dt 2 y t with y 0 u t S 0 and y ' 0 1. Solution: In this instance, the forcing function is the step function u t S above equation. This function is discontinuous at t of the S and, therefore, is not the solution of any linear homogeneous differential equation with constant coefficients. This is an example of an initial value problem that we cannot solve easily using the method of undetermined coefficients. Given that d2y t dt 2 y t u t S because of the linearity of the equation and of the Laplace transform operation, taking the Laplace transform of the differential equation, we have 2 °­ d y t L® y t 2 °¯ dt °½ ¾ L^ u t S ` °¿ . Using the derivative property and assuming all initial conditions are zero gives Chapter 4 324 ^ ` s2 1 Y s 1 e S s s Solving this expression for Y s yields two rational function components 1 e S s s2 1 s s2 1 Y s Using partial fractions, we can write this as ª 1 1 º S s 1 « » e s2 1 s 2 1 »¼ «¬ s Y s . Applying the inverse Laplace transform to the above equation, and using its linearity, we get sin t 1 cos t S y t u t S . Example 4.17. Determine the solution of the initial value problem d2y t dt 2 6 dy t dt 9y t 12e3t t 2 with y 0 Solution: Given that y '' t 6 y ' t 9 y t 12 e3t t 2 0 & y' 0 0. Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Solving IVPS 325 because of the linearity of the equation and of the Laplace transform operation, taking the Laplace transform of the differential equation, we have ^ L ¬ª y '' t º¼ 6 L ª¬ y ' t º¼ 9 L ª¬ y t º¼ 12 L e3t t 2 ` ­ L ª y '' t º s 2 L ª¬ y t º¼ sy 0 y ' 0 ½ ° ¬ ¼ ° ® ¾ ' °¯ L ª¬ y t º¼ sL ª¬ y t º¼ y 0 °¿ using , we get ^ª¬s L ª¬ y t º¼ sy 0 y 0 º¼ 6 ª¬sL ª¬ y t º¼ y 0 º¼ 9L ª¬ y t º¼ ` s 24 3 2 ' This algebraic equation can be solved for L L ª¬ y t º¼ ^ y t ` as 24 s 3 5 . Thus, we can write the time-domain solution y t as y t e 3t t 4 . It should be noted from the above examples, as we have noted in previous chapters, that the distinct advantage of using the Laplace transform is that it enables us to replace the operation of differentiation with an algebraic operation. Consequently, by taking the Laplace transform of each term in a differential equation, it is converted into an algebraic equation in the S domain. This may then be rearranged using algebraic rules (partial fractions) to obtain an expression for the Laplace transform of the 3 Chapter 4 326 response; the desired time response is then obtained by taking the inverse transform. Example 4.18. Determine the solution of the boundary value problem d2y t dt 2 9y t cos 2t with y 0 §S · 1, y ¨ ¸ 1. ©2¹ Solution: Since y ' 0 is not given, we assume y ' 0 a. Because of the linearity of the equation and of the Laplace transform operation, taking the Laplace transform of the differential equation, we have L ª¬ y '' t ¼º 9 L ª¬ y t º¼ L > cos 2t @ '' 2 ' ­ ½ ° L ¬ª y t ¼º s L ª¬ y t º¼ sy 0 y 0 ° ® ¾ ' °¯ L ª¬ y t º¼ sL ª¬ y t º¼ y 0 °¿ solving for L ^ y t ` gives L ª¬ y t º¼ sa s s2 9 s2 9 s2 4 It is now necessary to invert . L ^ y t ` . To accomplish this, some algebraic manipulation is necessary if we are to identify the terms on the Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Solving IVPS 327 right with the entries in Table 2.1. When expressed in terms of partial fractions, after a little manipulation, L L ª¬ y t º¼ ^ y t ` becomes a 1 s 4 s 2 s 9 5 s 9 5 s2 9 2 . Applying the inverse Laplace transform to the above equation, and using its linearity, results in a 1 4 sin 3t cos 2t cos 3t 3 5 5 y t when t S 2 1 a 1 a 3 5 12 5 . Hence, the solution is y t 4 1 4 sin 3t cos 2t cos 3t 5 5 5 Thus, y t 1 cos 2t 4sin 3t 4 cos 3t . 5 Chapter 4 328 Example 4.19. Obtain the solution of the fourth-order differential equation d4y t K dt 4 along with the boundary conditions y 0 y '' 0 y d y '' d 0. Solution: Assuming that the Laplace transform of the solution Y s exists, and using the fact that L is a linear operator, we take the Laplace transform of the above differential equation and write ­° d 4 y t L® 4 ¯° dt ½° ¾ L^ K ` ¿° L ª¬ y '''' t º¼ K s Using the derivative formula, we get s 4Y s s 3 y 0 s 2 y ' 0 sy '' 0 y ''' 0 Using the given initial conditions, we get s 4Y s s 2 y ' 0 y ''' 0 K s The two unknown initial conditions are replaced with K s . Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Solving IVPS y' 0 A and y '' 0 Y s K A B s5 s 2 s 4 329 B Taking the inverse Laplace transform of each term on the right, and using the linearity property of the Laplace transform, we find that Kt 4 Bt 3 At 24 6 . y t The boundary conditions on the right-hand side are now satisfied y d Kd 4 Bd 3 Ad 24 6 y '' d Kd 2 Kd Bd 0 B 2 2 and A kd 3 . 24 0 Finally, the desired solution of the boundary value problem is Kt 4 Kd 3 Kd 3 t t . 24 24 12 y t Example 4.20. Obtain the solution of the second-order differential equation d2y t dt 2 dy t dt f t , f t along with the initial conditions ­1 0 t 1 ® ¯0 t ! 1 y' 0 0 and y '' 0 1. Chapter 4 330 Solution: Assuming that Laplace transform of the solution Y s exists and using the fact that L is a linear operator, we take the Laplace transform of the above differential equation and write ­° d 2 y t dy t L® 2 dt °¯ dt ½° ¾ L^ f t °¿ ` ^ L ª¬ y '' t º¼ L ª¬ y ' t º¼ L f1 t f 2 t f1 t u t a ` 1 e s s s Y s 1 s s 2 Y s 1 e s 1 2 2 s s 1 s s 1 s s 1 Y s 1 e s 1 2 2 s s 1 s s 1 s s 1 . We begin by finding the partial fraction expansion for Y s . Partial fraction expansion of the first term of the right side of the above equation gives 1 s 1 s2 A B C 2 s 1 s s where A, B, and C are real numbers to be determined. Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Solving IVPS ª d ­ 1 ½º ª1º 1, B « ® A « 2» ¾» ¬ s ¼ s 1 ¬ ds ¯ s 1 ¿¼ s 0 C ª 1 º « » ¬« s 1 ¼» s 0 1 s 1 s2 331 1, 1, 1 1 1 2 s 1 s s . Partial fraction expansion of the third term of the right side of the above equation gives 1 s 1 s A B s 1 s where A and B are real numbers to be determined. ª1 º A « » ¬ s ¼ s 1 1 , B Hence, the given function Y Y s ª 1 º 1, «¬ s 1 »¼ s 0 1 s 1 s 1 1 s 1 s . s can be expanded as § 1 1 1 1 1 1· 1 1 2 e s ¨ 2 ¸ ¨ s 1 s s ¸ s 1 s s 1 s s © ¹ . Now that we have obtained the partial fraction expansion, taking the inverse Laplace transform of each term on the right and using the linearity property of the Laplace transform, we find that Chapter 4 332 ­ ½ 1 1 ·° ° § 1 ­1½ 2 ¸¾ L1 ® 2 ¾ L1 ®e s ¨ ¨ ¸ ¯s ¿ ° ¯ © s 1 s s ¹° ¿. y t Finally, using the transform pairs established in Table 2.1, we have y t t e t 1 t 2 u t 1 . Example 4.21. Obtain the solution of the second-order differential equation d2y t dt 2 4y t e 3t along with the initial conditions y 0 0 y' 0 . Solution: Assuming that Laplace transform of the solution Y s exists and using the fact that L is a linear operator, we take the Laplace transform of the above differential equation and write ­° d 2 y t 4y t L® 2 °¯ dt ½° 3t ¾ L e °¿ ^ ` L ª¬ y '' t º¼ 4 L ª¬ y t º¼ 1 s 3 ^ª¬s Y s sy 0 y 0 º¼ 4Y s ` s 1 3 . 2 ' Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Solving IVPS It is now necessary to invert Y 333 s . To accomplish this, some algebraic manipulation is necessary to identify the terms on the right with the entries in Table 2.1. When expressed in terms of partial fractions, after a little manipulation, Y s becomes Y s 6 s2 4 s 3 Y s 6 s 4 s 3 2 6 s3 s2 s 2 A B C s 3 s2 s2 where A, B, and C are real numbers to be determined. ª º ª º ª º 6 1 6 1 6 1 , B « , C « A « » » » «¬ s 3 s 2 ¼» s 2 20 ¬« s 2 s 2 ¼» s 2 5 ¬« s 2 s 3 ¼» s 2 4 Y s 1 1 1 1 1 1 5 s 3 20 s 2 4 s 2 . Applying the inverse Laplace transform to the above equation, and using its linearity, results in y t 1 3t 1 2t 1 2t e e e . 5 20 4 Chapter 4 334 Example 4.22. Obtain the solution of the first-order differential equation 2 dy t dt 2y t sin 2t along with the initial conditions y 0 2. Solution: Assuming that the Laplace transform of the solution Y s exists, and using the fact that L is a linear operator, we take the Laplace transform of the above differential equation and write ­ dy t ½ L ®2 2 y t ¾ L ^ sin 2t ` ¯ dt ¿ L ª¬ y ' t º¼ L ª¬ y t º¼ 1 s2 4 ^¬ªsY s y 0 ¼º Y s ` s 1 4 . 2 It is now necessary to invert Y s . To accomplish this, some algebraic manipulation is necessary to identify the terms on the right with the entries in Table 2.1. When expressed in terms of partial fractions, after a little manipulation, Y s becomes Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Solving IVPS 1 2 s 1 s 1 s2 4 Y s . We first observe that the quadratic factor s2 4 and s 1 s 2 4 is irreducible. Since are non-repeated factors, the partial fraction expansion has the form ª º 1 « » «¬ s 1 s 2 4 »¼ A Bs C 2 s 1 s 4 . We can use the cover-up method to find A, B, and C, as follows A ª 1 º « 2 » «¬ s 4 »¼ s 1 > Bs C @s 2i 2 Bi C 1 5 ª 1 º « » «¬ s 1 »¼ s 2i 1 1 2i 1 1 2i ­° 1 2i ½° 1 2 i ® ¾ ¯° 1 2i ¿° 5 5 Since the real and imaginary parts are equal on both sides, we get B 1 &C 5 Hence, we have 1 5. 335 Chapter 4 336 ª º 1 « » «¬ s 1 s 2 4 ¼» 1 °­ 1 s 1 °½ 1 °­ 1 s 1 ½° 2 2 2 ® ¾ ® ¾ 5 ° s 1 s 4 ° 5 ° s 1 s 4 s 4 ¿° ¯ ¿ ¯ . Taking the inverse Laplace transform of each term on the right, and using the linearity property of the Laplace transform, we find that y t 1 ­° 1 § 1 · 1 § s · 1 § 1 · ½° 1 § 2 · ¸ L ¨ ¸¾ L ¨ ®L ¨ ¸ L ¨¨ 2 ¨ s 1 ¸¸ ¸ ¨ s2 4 ¸° 5 ° © s 1 ¹ s 4 © ¹ © ¹ © ¹ ¯ ¿ Finally, using the transform pairs established in Table 2.1, we have y t 1­ t 1 ½ t ®e cos 2t sin 2t ¾ 2e . 5¯ 2 ¿ Example 4.23. Obtain the solution of the integro-differential equation dy t dt t y t ³ cos 2 t u du. 0 along with the initial condition y 0 2. Solution: Assuming that the Laplace transform of the solution Y s exists, and using the fact that L is a linear operator, we take the Laplace transform of the above differential equation and write ­ dy t y t L® dt ¯ ½ °­ t ¾ L ® ³ cos 2 t u du. ¿ °¯ 0 °½ ¾ °¿ Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Solving IVPS 337 L ª¬ y ' t º¼ L ª¬ y t º¼ L ^1 cos t` ^ª¬sY s y 0 º¼ Y s ` L >1@u L >cos 2t @ s 1 Y s 1 2 s 4 2 . It is now necessary to invert Y s . To accomplish this, some algebraic manipulation is necessary if we are to identify the terms on the right with the entries in Table 2.1. When expressed in terms of partial fractions, after a little manipulation, Y Y s s becomes 1 2 2 s 1 s 1 s 4 Using partial fraction decomposition, we can write 1 s 1 s2 4 1 ­° 1 1 ½° s 2 2 ® ¾ 5 ° s 1 s 4 s 4 ¯ ¿° Thus, Y s 1 ­° 1 s 1 ½° 2 ® ¾ 2 5 ° s 1 s2 4 s 1 s 4 ¯ ¿° . Taking the inverse Laplace transform of each term on the right, and using the linearity property of the Laplace transform, we find that Chapter 4 338 1 ­° 1 § 1 · 1 § s · 1 § 1 · ½° 1 · ¸ L ¨ ¸ ¾ 2 L1 ¨§ ®L ¨ ¸ L ¨¨ 2 ¸ 2 ¸ ¨ s 4 ¸° s 1 ¹ 5 ° © s 1 ¹ s 4 © © ¹ © ¹¿ ¯ Y s . Finally, using the transform pairs established in Table 2.1, we have 1­ t 1 ½ ®11e cos 2t sin 2t ¾ . 5¯ 2 ¿ y t Example 4.24. Use the Laplace transform technique to solve the initial value problem d2y t dt 2 4 dy t dt 3y t e2t 0 y' 0 . along with the initial conditions y 0 Solution: Assuming that the Laplace transform of the solution Y s exists, and using the fact that L is a linear operator, we take the Laplace transform of the above differential equation to write ­° d 2 y t ½° dy t 2 t L® y t 4 3 ¾ L e 2 dt ¯° dt ¿° ^ ` L ª¬ y '' t º¼ 4 L ª¬ y '' t º¼ 3L ª¬ y t º¼ 1 s2 Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Solving IVPS 2 ' ¬ª s Y s sy 0 y 0 ¼º 4 ¬ª sY s y 0 º¼ 3Y s 339 1 s2 . Imposing the initial conditions, we obtain the Laplace transform of the solution as s 2 4s 3 Y s 1 s2 Y s 1 s 1 s 2 s 3 Y s 1 s 1 s 2 s 3 A B C s 1 s 2 s3 where A, B, and C are real numbers to be determined. ª º 1 A « » ¬« s 2 s 3 ¼» s 1 C ª º 1 « » ¬« s 1 s 2 ¼» s 3 Hence, the function Y Y s 1 , 6 B ª º 1 « » ¬« s 1 s 3 ¼» s 2 1 , 15 1 10 s can be expanded as 1 ­ 1 ½ 1 ­° 1 ½° 1 ­° 1 ½° ® ¾ ® ¾ ® ¾ 6 ¯ s 1 ¿ 15 ¯° s 2 ¿° 10 ¯° s 3 ¿° . Taking the inverse Laplace transform of each term on the right, and using the linearity property of the Laplace transform, we find that Chapter 4 340 1 t 1 2t 1 3t e e e . 6 15 10 y t The Laplace transform method is useful for solving non-homogeneous linear differential equations and initial value problems with constant coefficients when the forcing function is a discontinuous function or an impulse function with a Laplace transform. Forcing functions, which are discontinuous functions or impulse functions, frequently occur in electrical and mechanical systems. The following example shows how to use the Laplace transform method to obtain a general solution for a linear differential equation with constant coefficients when the forcing function is an impulse. Example 4.25. Obtain the solution of the fourth-order differential equation d4y t dt 4 2 d3y t dt 3 d2y t dt 2 2 dy t dt G t along with the initial condition y 0 1 and y ' 0 y '' 0 y ''' 0 0. Solution: Assuming that the Laplace transform of the solution Y s exists, and using the fact that L is a linear operator, we take the Laplace transform of the above differential equation and write ­° d 4 y t d3y t d2y t dy t L® 2 2 4 3 2 dt dt dt ¯° dt ½° ¾ L^ G t ¿° ` Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Solving IVPS 341 L ª¬ y '''' t º¼ 2 L ª¬ y ''' t º¼ L ª¬ y '' t º¼ 2 L ª¬ y ' t º¼ 1 s 4 2s3 s 2 2s Y s s 3 Y s s3 1 s 4 2s3 s 2 2s Y s s3 1 s s 1 s 1 s 2 1 . We begin by finding the partial fraction expansion for Y s . The denominator consists of four distinct linear factors and so the expansion has the form s3 1 s s 1 s 1 s 2 A B C D s s 1 s 1 s2 where A, B, C, and D are real numbers to be determined. ª º s3 1 A « » ¬« s 1 s 1 s 2 ¼» s 0 1 , 2 B ª º s3 1 « » «¬ s s 1 s 2 »¼ s 1 1, C D ª º s3 1 « » «¬ s 1 s s 1 »¼ s 2 3 2 . ª º s3 1 « » «¬ s 1 s s 2 »¼ s 1 0, Chapter 4 342 Hence, the function Y s can be expanded as 11 1 3 1 2 s s 1 2 s 2 Y s . Now that we have obtained the partial fraction expansion, taking the inverse Laplace transform of each term on the right and using the linearity property of the Laplace transform, we find that 1 1 ­ 1 ½ 1 ­° 1 ½° 3 1 ­° 1 ½° L ® ¾ L ® ¾ L ® ¾ 2 ¯s¿ ¯° s 1 ¿° 2 ¯° s 2 ¿° y t . Finally, using the transform pairs established in Table 2.1, we have y t 1 t 3 2t e e . 2 2 Example 4.26. Obtain the solution of the second-order differential equation d2y t dt 2 4 dy t dt 4y t f t , f (t ) along with the initial conditions y 0 Solution: First, we find the Laplace transform of f (t ) t 1 t 1 , t t 0. t 1 t 1 , t t 0 0 y' 0 . Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Solving IVPS 0 d t d1 t !1 ­2 f (t ) ® ¯2t In terms of the unit step function, f f (t ) 343 t can be expressed as f1 t ^ f 2 t f1 t ` u t a f (t ) 2 > 2t 2@ u t 1 . Then, taking the Laplace transform L ^ f (t )` L > 2@ L ^ 2t 2 u t 1 ` which, on using the result in (1.7), gives L ^ f (t )` 2 s e L ^ f1 (t )` s f1 (t 1) 2t 2 replace t t 1 f1 (t ) 2t then its Laplace transform is L ^ f1 (t )` Eq. (4.1) becomes 2 s2 (4.1) Chapter 4 344 L ^ f (t )` 2 s § 2 · e ¨ 2 ¸ s ©s ¹ thus, L ^ f (t )` 2 s e s . s2 Now we start solving the given initial value problem. Assuming that the Laplace transform of the solution Y s exists, and using the fact that L is a linear operator, we take the Laplace transform of the above differential equation and write ­° d 2 y t dy t L® 4 4y t 2 dt ¯° dt ½° ¾ L^ f t ` ¿° L ª¬ y '' t º¼ 4 L ª¬ y ' t º¼ 4 L ª¬ y t º¼ 2 s e s . 2 s ^ª¬s Y s sy 0 y 0 º¼ ª¬sY s y 0 º¼ 4Y s ` s2 s e . 2 s ' 2 It is now necessary to invert Y s . To accomplish this, some algebraic manipulation is necessary to identify the terms on the right with the entries in Table 2.1. When expressed in terms of partial fractions, after a little manipulation, Y s becomes Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Solving IVPS Y s Y s 2 2 s s2 2 345 s e s ª º 1 1 e s 2 2« » 2 2 s s 2 »¼ «¬ s s 2 . Applying the inverse Laplace transform to the above equation, and using the linearity of the inverse Laplace transform, results in y t ª ­° ½° 1 ­° s ½°º 1 1 1 « » L ®e 2 2 L ® 2¾ 2¾ «¬ °¯ s s 2 °¿ °¯ s s 2 °¿»¼ . Using the convolution theorem and the second shifting theorem, we have y t 1 ­ t ½ 1 2 ® e2t e2t 1 ¾ t 2 te2 t 1 u t 1 . 2 ¯2 ¿ 2 ^ ` Example 4.27. Obtain the solution of the integro-differential equation dy t dt t y t t u ³ e u du. 0 along with the initial condition y 0 1. Solution: Assuming that the Laplace transform of the solution Y s exists, and using the fact that L is a linear operator, we take the Laplace transform of the above differential equation and write Chapter 4 346 ½ °­ t u °½ ¾ L ® ³ e t u du. ¾ ¿ °¯ 0 ¿° ­ dy t L® y t ¯ dt ^ L ª¬ y ' t º¼ L ª¬ y t º¼ L et t ` ^ª¬sY s y 0 º¼ Y s ` L ª¬e º¼ u L >t @ t 1 1 s s 1 s 1 Y s 2 . It is now necessary to invert Y s . To accomplish this, some algebraic manipulation is necessary if we are to identify the terms on the right with the entries in Table 2.1. When expressed in terms of partial fractions, after a little manipulation, Y 1 Y s 2 s s 1 2 s becomes 1 s 1 . Using partial fraction decomposition, we can write 1 s2 s 1 2 2 1 2 1 2 2 s s s 1 s 1 Thus, Y s 2 1 3 1 2 2 s s s 1 s 1 . . Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Solving IVPS 347 Taking the inverse Laplace transform of each term on the right, and using the linearity property of the Laplace transform, we find that y t § 3 · 1 § 1 · §2· § 1· ¸ L1 ¨ ¸ L1 ¨ 2 ¸ L1 ¨ L ¨ 2 ¨ s 1 ¸¸ ¨ ¸ ©s¹ ©s ¹ s 1 © ¹ © ¹ . Finally, using the transform pairs established in Table 2.1, we have y t 2 t 3et tet . 4.3 Differential Equations with Variable Coefficients We have the multiplication by t formula L ^t f t ` d L^ f t ` ds which is taken to be the nth-derivative of f ^ L t fn t ` dsd L ^ f n t ` t , then . Using the derivative formula ^ L t fn t ` dsd ^s L ^ f t ` s n n 1 This equation can be used to transform a linear differential equation with variable coefficients into a differential equation involving the transform. The following examples show how to use the Laplace transform method to obtain the general solution of linear differential equations with variable coefficients. ` f 0 s n 2 f ' 0 ...... f n 1 0 . Chapter 4 348 Example 4.28. Determine the solution of the initial value problem t d2y t dt 2 2 dy t dt ty t cos t with y 0 1. Solution: Because of the linearity of the equation and the Laplace transform operation, taking the Laplace transform of the differential equation, we have L ª¬ty '' t º¼ 2 L ª¬ y ' t º¼ L ª¬ty t º¼ L ^ cos t ` d ­ L ª y t ¼º ® L ¬ªty t ¼º ds ¬ Using ¯ ` dsd ^Y s ` ¾¿½ ^ . , we get d 2 d s s Y s sy 0 y ' 0 2 ^sY s y 0 ` ^Y s ` 2 ds ds s 1 ^ ` d s ­ d ½ ® s 2 Y s 2sY s ¾ y 0 0 2sY s 2 y 0 ^Y s ` 2 ds s 1 ¯ ds ¿ s2 1 d s Y s 1 2 ds s 1 d Y s ds s s 2 2 s 1 s2 1 . Taking the inverse Laplace transform and using ­ 1 ­ d ½ ® L ® ^Y s `¾ ty t ¯ ds ¿ ¯ ½ ¾ ¿ , we get Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Solving IVPS 349 1 sin t t sin t 2 . ty t Thus, y t 1§ 2· ¨1 ¸ sin t. 2© t ¹ Example 4.29. Determine the solution of the initial value problem t d2y t dy t t y t 2 dt dt with y 0 0 0 and y ' 0 2. Solution: Because of the linearity of the equations and the Laplace transform operation, we have 2 dy t °­ d y t °½ L ®t t y t ¾ 0 2 dt °¯ dt °¿ . Using, L ^ty t ` Y ' s ­° d 2 y t ½° 2 ' L ®t ¾ 2sY s s Y s 2 ¯° dt ¿° Chapter 4 350 ­ dy t ½ L ®t ¾ ¯ dt ¿ Y s sY ' s . Therefore 2 dy t °­ d y t °½ L ®t t y t ¾ 2 sY s s s 1 Y ' s 2 dt ¯° dt ¿° Y' s Y s 2ds s 1 0 . On integration, we get log s 1 log Y s 2 log C ­° C ½° log ^Y s ` log ® 2¾ ¯° s 1 ¿° Y s C s 1 2 . Taking the inverse Laplace on both sides of the above equation, we get y t Ctet . Since y' t Ctet Cet Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Solving IVPS y' 0 351 C 2, therefore 2tet y t . Example 4.30. Determine the solution of the initial value problem t d2y t dt 2 dy t dt ty t 2 and y ' 0 0 with y 0 0. Solution: Because of the linearity of the equation and the Laplace transform operation, taking the Laplace transform of the differential equation, we have L ª¬ty '' t º¼ L ª¬ y ' t º¼ L ª¬ty t º¼ 0 d ­ L ª¬ y t º¼ ® L ª¬ty t º¼ ds ¯ Using ` dsd ^Y s ` ½¾¿ ^ . , we get d 2 d s Y s sy 0 y ' 0 ^sY s y 0 ` ^Y s ` 0 ds ds ^ ` d ­ d ½ ® s 2 Y s 2sY s ¾ y 0 0 sY s y 0 ^Y s ` 0 ds ¯ ds ¿ d s Y s 2 Y s ds s 1 0 Chapter 4 352 implying d Y s ds s 2 Y s s 1 dY s s 2 ds 0 Y s s 1 . On integration, we get 1 ln Y s ln s 2 1 2 ln Y s s2 1 ln c ln c c Y s s2 1 . Taking the inverse Laplace transform on both sides of the above equation, we get ­ ° cL ® ° ¯ ½ ° ¾ c J0 t . 2 s 1 ° ¿ 1 1 y t Example 4.31. (Bessel’s equation) Determine the solution of the initial value problem x2 d2y x dx 2 x dy x dx x2 y x 0 with y 0 1 and y ' 0 0. Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Solving IVPS 353 Solution: Dividing the given differential equation by x and replacing x t , we get t y '' t y ' t ty t 0 . Take the Laplace transform of both sides of the above differential equation L ª¬ty '' t º¼ L ª¬ y ' t º¼ L ª¬ty t º¼ 0 d ­ L ª¬ y t º¼ ® L ª¬ty t º¼ ds ¯ Using ^ . ` dsd ^Y s ` ½¾¿ , we get d 2 d s Y s sy 0 y ' 0 ^sY s y 0 ` ^Y s ` 0 ds ds ^ ` d ­ d ½ ® s 2 Y s 2sY s ¾ y 0 0 sY s y 0 ^Y s ` 0 ds ¯ ds ¿ d s Y s 2 Y s ds s 1 implying d Y s ds s 2 Y s s 1 0 Chapter 4 354 dY s s 2 ds 0 Y s s 1 . On integration, we get 1 ln Y s ln s 2 1 2 ln c s2 1 ln Y s ln c c Y s s2 1 Taking the inverse Laplace on both sides of above equation, we get y t ­ ° cL ® ° ¯ 1 ½ ° ¾ c J0 t . 2 s 1 ° ¿ 1 Example 4.32. Use the Laplace transform to find the output y t the system described by d2y t dt 2 3 dy t dt 2y t dx t dt 3x t with input given by x t e 5t u t with y 0 Solution: 1 and y ' 0 2. of Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Solving IVPS 355 Given that y '' t 3 y ' t 2 y t x' t 3x t . Because of the linearity of the equation and the Laplace transform operation, taking the Laplace transform of the differential equation, we have ^ ` ^ ` ^ ` L y '' t 3L y ' t 2 L ^ y t ` L x ' t 3L ^ x t ` '' 2 ' ­ ½ ° L ¬ª y t ¼º s L ª¬ y t º¼ sy 0 y 0 ° ® ¾ ' ° L ª¬ y t º¼ sL ª¬ y t º¼ y 0 °¿ using ¯ , we get ^ª¬s L ª¬ y t º¼ sy 0 y 0 º¼ 3 ª¬sL ª¬ y t º¼ y 0 º¼ 2L ª¬ y t º¼ ` ª¬sL ª¬ x t º¼ x 0 º¼ 3L ª¬ x t º¼ 2 ' L^ y t ` s 3 L ^x t ` 2 s 3s 2 s5 2 s 3s 2 we have, L ^x t ` 1 , s5 It is now necessary to invert L ^ y t ` . To accomplish this, some algebraic manipulation is necessary if we are to identify the terms on the right with the entries in Table 2.1. When expressed in terms of partial fractions, after a little manipulation, L ^ y t ` becomes Chapter 4 356 L^ y t ` L^ y t ` s3 s 2 3s 2 s 5 s5 s 2 3s 2 s 2 11s 28 s 2 3s 2 s 5 . Using partial fractions, we have L^ y t ` s 2 11s 28 s 1 s 2 s 5 10 1 9 3 6 2 s 1 s 2 s5 . Applying the inverse Laplace transform to the above equation, and using its linearity, results in 9 t 10 2t 1 5t e e e . 2 3 6 y t Example 4.33. Obtain the solution of the second differential equation d2y t dt 2 4 dy t dt 5y t 8sin t along with the initial conditions y 0 0 y' 0 . Solution: Assuming that the Laplace transform of the solution Y s exists, and using the fact that L is a linear operator, we take the Laplace transform of the above differential equation and write Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Solving IVPS 357 2 dy t °­ d y t °½ 4 5 y t ¾ 8L ^sin t` L® 2 dt ¯° dt ¿° L ª¬ y '' t º¼ 4 L ª¬ y ' t º¼ 5L ª¬ y t º¼ 8 s 1 2 ª¬ s 2Y s sy 0 y ' 0 º¼ 4 ª¬ sY s y 0 º¼ 5Y s 8 s2 1 . Imposing the initial conditions, we obtain the Laplace transform of the solution as s 2 4s 5 Y s Y s 8 s2 1 8 s 1 s 2 4s 5 2 . Using partial fractions, we can write this as Y s As B Cs D 2 2 s 1 s 4s 5 . We expand this S domain solution into partial fractions as Y s s 1 s3 s2 1 s 2 4s 5 358 Chapter 4 Y s s 1 s2 1 s2 1 s2 1 s 2 4s 5 s 2 4s 5 . Applying the inverse Laplace transform to the above equation, and using the linearity of the inverse Laplace transform, results in y t cos t sin t e2t cos t e2t sin t . Example 4.34. Use the Laplace transform to find the output y t of the system described by dy t dt 5y t x t with input given by x t 3e 2t u t with y 0 2. Solution: Given that y' t 5 y t x t because of the linearity of the equation and the Laplace transform operation, taking the Laplace transform of the differential equation, we have ^ ` L y ' t 5L ^ y t ` L ^ x t ` ^ L ª¬ y t º¼ sL ª¬ y t º¼ y 0 ` , we get ' Using . Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Solving IVPS 359 ª sL ª¬ y t º¼ y 0 º 5L ª¬ y t º¼ L ª¬ x t º¼ ¬ ¼ . We have L ^x t ` 3 , s2 and thus L^ y t ` 3 s2 s5 2 s5 It is now necessary to invert L ^ y t ` . To accomplish this, some algebraic manipulation is necessary to identify the terms on the right with the entries in Table 2.1. When expressed in terms of partial fractions, after a little manipulation, L ^ y t ` becomes L^ y t ` 1 1 2 s2 s5 s5 L^ y t ` 1 3 s2 s5 . Applying the inverse Laplace transform to the above equation, and using its linearity, results in y t e2t 3e5t . Chapter 4 360 Example 4.35. Determine the solution of the initial value problem d2y t dt 2 3 dy t dt 2y t 4t with y 0 0 y' 0 . Solution: Because of the linearity of the equation and the Laplace transform operation, taking the Laplace transform of the differential equation, we have ^ ` ^ ` L y '' t 3L y ' t 2 L ^ y t ` 4 L ^t` 4 ª s 2 L ^ y t ` sy 0 y ' 0 º 3 ª sL ^ y t ` y 0 º 2 L ^ y t ` 2 ¬ ¼ ¬ ¼ s . Find the expression L ^ y t ` in the form of an algebraic function. Substituting the values for y 0 0 y ' 0 ; rearranging the above equation gives s 2 3s 2 L ^ y t ` 4 s2 . This algebraic equation can be solved for L L^ y t ` 4 s s 1 s 3 2 . ^ y t ` as Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Solving IVPS 361 This solution is in the form of the product of two known Laplace transforms; we can invert either using partial fractions. Using the partial fractions yields 4 s ( s 1)( s 2) 2 4 A B C D 2 s s s 1 s 2 As( s 1)( s 2) B( s 1)( s 2) Cs 2 ( s 2) Ds 2 ( s 1) Let s 0 B 2 s -1 C 4 s -2 D -1 A 3 Thus, F ( s ) 3 2 4 1 2 s s s 1 s 2 Applying the inverse Laplace transform to the above equation, and using its linearity, results in y t 3 2t 4et e2t . 4.4 Total Response of the System Using the Laplace Transform LTI systems can be explained by a constant-coefficient differential equation. The response of the system is derived by solving the differential equation. The Laplace transform converts the differential equation in the time domain to an algebraic equation in the Laplace domain. These algebraic equations can be solved to find the solution. The total response of the system can be expressed as Chapter 4 362 Total response Natural response Forced response The usual response of the system is solely due to the initial conditions. This is also the zero input response, i.e. when the externally-applied input is zero. The forced response is due to the externally-applied input function. The forced response consists of the steady-state response and the transient response. The forced response is also a zero state response, i.e. when the initial conditions are zero. 4.4.1 Impulse Response and Transfer Function For a linear ODE with constant coefficients, the output is derived as a convolution of its impulse response function h t y t h t *x t and the input x t : x t * h t , assuming zero initial states. This has been demonstrated in Chapter 3 for second and higher-order systems in the time domain, and it also holds for higher-order LTI systems. Taking the convolution property of the Laplace transform, the output is the product of Y s transforms H s X s H s H s X s , L ^h t ` , is the transfer function, and X s where L ^ x t ` , is the input. From this expression, we find that the impulse response function of a system is generated when x t G t . Example 4.36. Find the forced response of the system with the differential equation given by d2y t dt 2 5 dy t dt 6y t x t Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Solving IVPS to the input given by x t 363 et u t . Solution: We first find the transfer function of the system. The solution process is the same as for example 1. Taking the Laplace transform of the given differential equation and imposing the initial conditions, we find, successively ­° d 2 y t ½° d2y t 2 t 2 4 4 L® y t ¾ L e t 2 2 dt ¯° dt ¿° ^ ^ ` ^ ` ` L y '' t 5 L y ' t 6 L ^ y t ` L ^ x t ` '' 2 2 ­ ° L ¬ª y t ¼º s L ª¬ y t º¼ s Y s ® ' ° L ª¬ y t º¼ sL ª¬ y t º¼ sY s ¯ using s 2 5s 6 Y s T .F H s X s Y s X s 1 s 2 5s 6 Thus, H s Y s X s 1 s 5s 6 2 . ½ ° ¾ ¿° Chapter 4 364 1 Y s s2 s3 X s we have X s 1 . s 1 Y s 1 s 1 s 2 s 3 . We begin by finding the partial fraction expansion for Y s . The denominator consists of three distinct linear factors and so the expansion has the form 1 s 1 s 2 s 3 Y s where A, B, and C are A B C s 1 s2 s3 real ª º 1 A « » «¬ s 2 s 3 »¼ s 1 1 , 2 ª º 1 « » «¬ s 1 s 2 »¼ s 3 1 , 2 C Y s numbers to be determined. ª º 1 B « » «¬ s 1 s 3 »¼ s 2 1 1 1 1 1 2 s 1 s2 2 s3 . 1, Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Solving IVPS 365 We take the inverse Laplace transform to find the solution. The response due to the input is the steady-state response and the response due to the poles of the system is the transient response § 1 t 2t 1 3t · ¨ e e e ¸u t . 2 ©2 ¹ h t Thus, § 1 t · § 2t 1 3t · ¨ e u t ¸ ¨ e e ¸ u t . 2 ©2 ¹ © ¹ h t Forced response = steady state response + transient response. Example 4.37. Find the natural response, forced response, and the total response of the system with the differential equation given by d2y t x t to the input given by x t y 0 5 dy t 6y t dt 2 dt 0 and y ' 0 u t . The initial conditions are 2. Solution: In this instance, the forcing function is the step function u t of the above equation. Therefore, this function is discontinuous and is not the solution of any linear homogeneous differential equation with constant coefficients. This example of an initial value problem that we cannot solve quickly uses undetermined coefficients. The advantage of the Laplace Chapter 4 366 transform method is that the above initial value problem’s solution can be obtained with one application of the method. Given that d2y t dt 2 5 dy t dt 6y t x t We first find the transfer function of the system. The solution process is the same as for example 1. Taking the Laplace transform of the given differential equation and imposing the initial conditions, we find, successively ­d2y t ½ dy t ° ° L® 5 6y t ¾ 2 dt ° dt ° ¯ ¿ L ^x t ` . We take the Laplace transform of each term of the left side of the given differential equation and apply the initial conditions ^ ` ^ ` L y '' t 5 L y ' t 6 L ^ y t ` L ^ x t ` '' 2 ' ­ ° L ¬ª y t ¼º s L ª¬ y t º¼ sy 0 y 0 ® ' ° L ª¬ y t º¼ sL ª¬ y t º¼ sY s y 0 using ¯ s 2 5s 6 Y s s 7 X s Solving this expression for components Y s ½ ° ¾ °¿ . yields two rational function Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Solving IVPS Y s Y s X s s 2 5s 6 X s s2 s3 367 s7 s 2 5s 6 s7 s2 s3 . The response due to the first term is due to the initial conditions and hence is the natural response YN s s7 s2 s3 . Using partial fraction expansion, we have YN s 5 4 s2 s3 . Applying the inverse Laplace transform to the above equation, and using the linearity of the inverse Laplace transform, results in yN t 5e 2t 4e 3t u t . The response due to the second term is the forced response. To find the forced response, we apply the input x t YF s X s s2 s3 u t . Chapter 4 368 YF s 1 s s2 s3 . It is now necessary to invert YF s . To accomplish this, some algebraic manipulation is necessary if we are to identify the terms on the right with the entries in Table 2.1. When expressed in terms of partial fractions, after a little manipulation, YF YF s s becomes 1§1· 1§ 1 · 1§ 1 · ¸ ¨ ¸ ¨ ¸ ¨ 6 © s ¹ 2 ¨© s 2 ¸¹ 3 ¨© s 3 ¸¹ . Applying the inverse Laplace transform to the above equation, and using the linearity of the inverse Laplace transform, results in yF t 1 3t §1 · § 1 2t · ¨ u t ¸ ¨ e u t e u t ¸. 3 ©6 ¹ © 2 ¹ The total response was given by the addition of the natural response and the forced response yT t y N t yF t 9 2t 11 3t §1 · ¨ u t e u t e u t ¸. 2 3 ©6 ¹ The natural response is the complementary function, and the forced response is the particular integral. This is easily checked as to whether it is the correct solution. Now, it is up to you whether our approach to solving this differential equation is easier than the alternatives, but we suggest that the Laplace transform method provides a straightforward solution to the differential equation. Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Solving IVPS 369 Example 4.38. Find the zero-input, zero-state, transient, steady-state, and complete responses of the system governed by the differential equation d2y t dt 2 4 dy t 4y t dt d 2x t dt 2 dx t 2x t dt with the initial conditions 0 and y ' 0 y 0 4 and the input x t u t , the unit-step function. Solution: We first find the transfer function of the system. Take the Laplace transform of the given differential equation and apply the initial conditions ^ ` ^ ` ^ ` ^ ` L y '' t 4 L y ' t 4 L ^ y t ` L x '' t L x ' t 2 L ^ x t ` '' 2 ' ­ ° L ¬ª y t ¼º s L ª¬ y t º¼ sy 0 y 0 ® ' °¯ L ª¬ y t º¼ sL ª¬ y t º¼ sY s y 0 using s 2 4s 4 Y s 2s 8 s 1 Solving this expression for 2 s . Y s yields two rational function components Y s ½ ° ¾ °¿ s2 s 2 2s 11 2 2 s s 4s 4 s 4s 4 . Chapter 4 370 The first term on the right-hand side is X s H s and corresponds to the zero-state response. The second term is due to the initial conditions and corresponds to the zero-input response. Expanding into partial fractions, we get 2 s s2 Y s s s2 2 2s 11 s s2 2 1 1 2 2 2 2 7 2 2 s s2 s2 s2 s2 . Taking the inverse Laplace transform, we get the complete response zero-input 1 1 § · 2 t 2 t 2 t 2 t ¨ u t e u t 2te u t ¸ 2e u t 7te u t 2 ©2 ¹ zero-state yT t y N t yF t yT t 5 2t §1 2 t · ¨ u e 5te ¸ u t . 2 ©2 ¹ 4.5 Systems of Linear Differential Equations Similar to how we can convert a single differential equation into a single algebraic equation using a Laplace transform, so we can convert a pair of differential equations into simultaneous algebraic equations. The differential equations we solve are linear and so a couple of linear differential equations will convert into simultaneous linear algebraic equations familiar from school. We first solve algebraic equations for each of the transformed functions and then find the inverse Laplace transforms in the usual way. The following example illustrates how to use the Laplace Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Solving IVPS 371 transform method to obtain the general solution of a system of linear differential equations with constant coefficients. Example 4.39. Determine solution of initial value problem d 2x t dt 2 with y 0 y t 1, x 0 dx t dy y t dt 4 0 and x ' 0 1. and dt 4x t Solution: Because of the linearity of the equations and of the Laplace transform operation, taking the Laplace to transform for both differential equations, we have s2 X s Y s 1 4 4s X s s 1 Y s Solving for X X s s H s 1 1 1 s 1 2 s 1 4 4s s 1 1 . gives 1 ; s s 4s 4 3 2 Chapter 4 372 s2 1 4 4s 1 Y s 1 s2 4 4s s 1 s 2 4s 4 s3 s 2 4s 4 . X s It is now necessary to invert and Y s . To accomplish this, some algebraic manipulation is necessary to identify the terms on the right with the entries in Table 2.1. When expressed in terms of partial fractions, after a little manipulation, X X s 1 s s 4s 4 3 2 2 Y s s 4s 4 s s 2 4s 4 3 s and Y s becomes A B C s 1 s2 s2 1 1 1 3 2 6 s 1 s2 s2 A B C s 1 s2 s2 1 2 3 2 3 s 1 s2 s2 . Applying the inverse Laplace transform to the above equations, and using the linearity of the inverse Laplace transform, results in x t 1 t 1 2t 1 2t e e e . 3 2 6 y t 1 t 2 e 2e 2t e 2t . 3 3 Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Solving IVPS 373 Example 4.40. Determine the solution of the initial value problem dx t dt 2 x t y t 2e5t and dy t dt x t 2 y t 3e2t y 0 0 x 0. Solution: Because of the linearity of the equations and the Laplace transform operation, taking the Laplace to transform to both differential equations, we have s 2 X s Y s 2 s 5 X s s 2 Y s 3 s2 . X s It is now necessary to invert and Y s . To accomplish this, some algebraic manipulation is necessary to identify the terms on the right with the entries in Table 2.1. When expressed in terms of partial fractions, after a little manipulation, X X s Y s s and Y s becomes 5 3 3 1 4 4 s 1 s2 s 3 s 5 2 s 2 5s 7 s 1 s 2 s 3 s 5 3s 13 s 1 s 3 s 5 5 1 4 1 4 s 1 s 3 s 5 . Chapter 4 374 Applying the inverse Laplace transform to the above equations and using the linearity of the inverse Laplace transform results in x t 5 t 3 e 3e 2t e3t e5t . 4 4 y t 5 1 e t e 3t e 5 t . 4 4 Example 4.41. Determine the solution of the initial value problem dy t dt 2y t z t dz t 0 and subject to the initial conditions dt y 0 2z t y t 1 and z 0 0 0. Solution: Because of the linearity of the equations and the Laplace transform operation, taking the Laplace to transform to both differential equations, we have ­ dy t ½ L® 2y t z t ¾ 0 ¯ dt ¿ ­ dz t ½ L ® 2z t y t ¾ 0 ¯ dt ¿ . The method for solving single differential equations carries over into systems of equations. After transforming each equation and making use of the initial conditions, we obtain Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Solving IVPS s2 Y s Z s 1 Y s s2 Z s 0 Solving for Y s and Z s gives 1 1 0 s2 Y s s2 s2 2 1 s2 1 s 2 1 s2 1 1 0 s2 1 s2 1 Z s 375 ; 1 2 s 2 1 . Applying the inverse Laplace transform to the above equations, and using the linearity of the inverse Laplace transform, results in y t e2t cos t z t e2t sin t . Example 4.42. Determine the solution of the initial value problem d 2x t dt 2 with 10 x t 4 y t y 0 0 0 and x 0 , x' 0 d2y t dt 2 1 and y ' 0 y t 4x t 1. 0 Chapter 4 376 Solution: Because of the linearity of the equations and the Laplace transform operation, taking the Laplace to transform to both differential equations, we have ­° d 2 x t L® 10 x t 4 y t 2 ¯° dt ½° ¾ 0 ¿° ­° d 2 y t L® y t 4x t 2 ¯° dt ½° ¾ 0 ¿° . The method for solving single differential equations carries over into systems of equations. After transforming each equation and making use of the initial conditions, we obtain s 2 10 X s 4Y s 1 4 X s s 2 1 Y s 1 Solving for X X s s . and Y s gives 4 1 1 s 2 1 s 2 10 4 4 s2 1 s2 s 2 2 s 2 12 ; Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Solving IVPS Y s s 2 10 1 4 1 377 s2 6 s 2 2 s 2 12 s 2 10 4 4 s2 1 X s It is now necessary to invert and Y s . To accomplish this, some algebraic manipulation is necessary to identify the terms on the right with the entries in Table 2.1. When expressed in terms of partial fractions, after a little manipulation, X X s s 2 s 2 2 s 2 12 2 Y s s 6 s 2 s 2 12 2 s and Y s becomes 6 1 5 5 2 2 s 2 s 12 2 3 5 5 2 2 s 2 s 12 Applying the inverse Laplace transform to the above equations, and using the linearity of the inverse Laplace transform, results in x t 1 sin 5 2 2t y t 2 sin 5 2 2t 6 sin 12t . 5 12 3 sin 12t . 5 12 Chapter 4 378 Example 4.43. Determine the solution of the initial value problem dy t dt 2x t sin 2t and 0, x 0 1. y 0 dx t dt 2y t cos 2t with Solution: Because of the linearity of the equations and the Laplace transform operation, taking the Laplace to transform to both differential equations, we have ­ dy t ½ L® 2 x t ¾ L ^sin 2t ` ¯ dt ¿ ­ dx t ½ L® 2 x t ¾ L ^cos 2t ` ¯ dt ¿ . The method for solving single differential equations carries over into systems of equations. After transforming each equation and making use of the initial conditions, we obtain 2 X s sY s 2 s2 4 sX s 2Y s s 1 s 1 Solving for X s 2 . and Y s gives Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Solving IVPS Y s 2 s2 4 X s 1ª 2 2s º « 2 » 2 2« s 4 4 s »¼ ¬ . 379 Applying the inverse Laplace transform to the above equation, and using the linearity of the inverse Laplace transform, results in x t 1 sin 2t 2 cos 2t . 2 y t sin 2t . Example 4.44. Determine the solution of the initial value problem d 2x t dy t sin t dt 2 dt with y 0 1, x 0 and 0, y ' 0 dx t d2y t dt dt 2 0 and x ' 0 1. cos t Solution: Because of the linearity of the equations and the Laplace transform operation, taking the Laplace to transform to both differential equations, we have 2 °­ d x t dy t L® 2 dt °¯ dt °½ ¾ L ^ sin t ` °¿ Chapter 4 380 2 °­ d y t dx t L ® 2 dt °¯ dt °½ ¾ L ^ cos t ` °¿ . The method for solving single differential equations carries over into systems of equations. After transforming each equation and making use of the initial conditions, we obtain 2s 2 1 s2 1 (4.2) § s2 2 · ¨ 2 ¸ © s 1 ¹ (4.3) 2 s X s sY s X s sY s Adding (4.2) and (4.3), we get X s s2 1 s2 1 2 (4.4) Using (4.4) in (4.3), we get Y s 1 2s s s2 1 2 . Applying the inverse Laplace transform to the above equations, and using the linearity of the inverse Laplace transform, results in x t t cos t . ­ 2 ½ ° s 1 ° t cos t L ® 2 ¾ 2 s 1 ° ° ¯ ¿ 1 Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Solving IVPS y t ­ ½ ° 2s ° L1 ® 2 ¾ 2 s 1 ° ° ¯ ¿ 1 t sin t . 381 t sin t . Example 4.45. Find the solution of the set of the differential equations dy t dt 2y t z t 0 and dz t subject to the initial conditions y 0 dt 2z t y t 1 and z 0 0 0. Solution: Because of the linearity of the equations and the Laplace transform operation, taking the Laplace transform, we have ­ dy t ½ L® 2y t z t ¾ 0 ¯ dt ¿ ­ dz t ½ L® 2z t y t ¾ 0 ¯ dt ¿ . The method for solving single differential equations carries over into systems of equations. After transforming each equation and making use of the initial conditions, we obtain s2 Y s Z s 1 Y s s2 Z s 0 Solving for Y . s and Z s gives Chapter 4 382 1 1 0 s2 Y s s2 2 s2 1 1 s2 s 2 1 ; s2 1 1 0 s2 1 1 s2 Z s 1 2 s 2 1 . Applying the inverse Laplace transform to the above equations, and using the linearity of the inverse Laplace transform, results in y t e2t cos t z t e2t sin t . Example 4.46 Determine solution of initial value problem d 2x t dt 2 2x t y t with y 0 0, x 0 0 d2y t and 0, x ' 0 dt 2 2y t x t 1 and y ' 0 0 1. Solution: Because of the linearity of the equations and the Laplace transform operation, taking the Laplace transform, we have s2 2 X s Y s 1 Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Solving IVPS X s s2 2 Y s Solving for X Y s . s and Y s gives 1 X s 1 1 1 s 2 2 2 s 2 1 1 s2 2 s 2 2 1 1 1 2 s 2 1 1 s2 2 1 s 3 2 ; 1 s 3 2 Thus, X s 1 s 3 Y s 1 s2 3 2 . Taking the inverse Laplace transform, we get x t 1 sin 3 3t . 383 Chapter 4 384 y t 1 sin 3 3t . Example 4.47. Determine the solution of the initial value problem dy t y t dt F t , y 0 where F t ­0 0 d t d S . ® ¯sin t t ! S 0 Solution: Given that dy t y t dt F t because of the linearity of the equation and the Laplace transform operation, taking the Laplace transform, we have sL ª¬ y t º¼ L ª¬ y t º¼ s 1 L ª¬ y t º¼ L ª¬ y t º¼ eS s y t L ª¬ F t º¼ 1 S s e s 1 2 1 s 1 s2 1 ­° ½° 1 L1 ®eS s ¾ 2 1 1 s s ¯° ¿° . Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Solving IVPS 385 Refer to example 2. 24 ª º 1­ 1 1 ½ t » L1 « ®e cos 2t sin 2t ¾ 2 2 ¿ «¬ s 1 s 1 »¼ 5 ¯ then, yt ­° ½° 1­ 1 1 ½ tS L1 ®eSs ¾ ®e cos2 t S sin2 t S ¾u t S . 2 2 s 1 s 1 ¿° 5 ¯ ¿ ¯° Thus, y t 1 ­ t S 1 ½ cos 2 t S sin 2 t S ¾ u t S ®e 5¯ 2 ¿ . Example 4.48. Obtain the solution of the differential equation d2 y t dt 2 y t 2u t 2 u t 4 , along with the initial conditions y 0 0 y' 0 . Solution: Assuming that the Laplace transform of the solution Y s exists and using the fact that L is a linear operator, we take the Laplace transform of the above differential equation and write ­° d 2 y t L® y t 2 ¯° dt ½° ¾ L ^2u t 2 u t 4 ` ¿° Chapter 4 386 L ª¬ y '' t º¼ L ª¬ y t º¼ ^ 2e2 s e4 s . s s ª¬ s 2Y s sy 0 y ' 0 º¼ Y s It is now necessary to invert Y ` 2e2 s e4 s s s . s . To accomplish this, some algebraic manipulation is necessary to identify the terms on the right with the entries in Table 2.1. When expressed in terms of partial fractions, after a little manipulation, Y Y s Y s s becomes 2e2 s e4 s 1 s s s2 1 2e 2 s e 4 s s s s2 1 . Applying the inverse Laplace transform to the above equation, and using its linearity, results in y t ­° ½° ­ ½° ­ 1 ½° 1 1 1 ° 4 s 1 ° L1 ®2e 2 s L e L ¾ ® ¾ ® 2 ¾ 2 2 1 1 1 s s s s s ¯° ¿° ¯° ¿° ¯° ¿° Using the convolution theorem Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Solving IVPS 387 ­° 1 ½° L1 ® 2 ¾ 1 cos t s s 1 °¯ °¿ . Finally, 2 1 cos t 2 u t 2 1 cos t 4 u t 3 sin t. y t Hence, the solution of the given initial value problem is 2 1 cos t 2 u t 2 1 cos t 4 u t 3 sin t. y t Example 4.49. Obtain the solution of the second-order differential equation d2y t dt 2 5 dy t dt 6y t 3G t 2 4G t 4 along with the initial conditions y 0 0 y' 0 . Solution: Assuming that the Laplace transform of the solution Y s exists, and using the fact that L is a linear operator, we take the Laplace transform of the above differential equation and write ­° d 2 y t dy t 5 6y t L® 2 dt ¯° dt ½° ¾ L ^ 3G t 2 4G t 4 ` ¿° L ª¬ y '' t º¼ 5 L ª¬ y ' t º¼ 6 L ª¬ y t º¼ 3e 2 s 4e 4 s Chapter 4 388 s 2 5s 6 Y s 3e 2 s 4e 4 s e 2 s e 4 s 4 s 2 5s 6 s 2 5s 6 Y s 3 Y s e 2 s e 4 s 3 4 s2 s3 s2 s3 . We begin by finding the partial fraction expansion for Y s . The denominator consists of two distinct linear factors and so the expansion has the form 1 s2 s3 A B s2 s3 where A and B are real numbers to be determined. ª 1 º 1, B A « » ¬« s 3 ¼» s 2 hence, the given function Y Y s ª 1 º « » ¬« s 2 ¼» s 3 1, s can be expanded as ª 1 ª 1 1 º 1 º 4 s 3e 2 s « » 4e « » s 3 »¼ s 3 »¼ «¬ s 2 «¬ s 2 . Now that we have obtained the partial fraction expansion, taking the inverse Laplace transform of each term on the right, and using the linearity property of the Laplace transform, we find that Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Solving IVPS y t 389 3 e 2 t 2 e 3 t 2 u t 2 4 e 2 t 4 e 3 t 4 u t 4 . Summary In this chapter, we have described and explained the solution of initial value problems. x LTI systems governed by differential equations, along with their initial conditions, have been analyzed by finding complete solutions. The advantage of the Laplace transform method when forcing functions, such as step functions and impulse functions, appear as inputs have been discussed with several examples. LTI systems governed by simultaneous differential equations and their initial conditions have also been analyzed by finding solutions. x The analysis of LTI systems has been given using Laplace transforms. Terms, such as impulse response, natural response, steady-state response, transient response, and forced response, have been explained. Simple examples have been solved to illustrate the relevant concepts. The zero state response and zero input response have also been described. CHAPTER 5 APPLICATION OF THE LAPLACE TRANSFORM TO LTI DIFFERENTIAL SYSTEMS: ELECTRICAL CIRCUITS AND MECHANICAL SYSTEMS 5.1 Introduction The most familiar application of Laplace transformations in the physical sciences is in analyzing mechanical system problems and electrical circuits. The Laplace transform is a handy tool for analyzing linear timeinvariant (LTI) electric circuits. We can use Laplace transforms to solve differential equations relating an input voltage/current signal to another output signal in the circuit. Laplace transforms can also be used to analyze a circuit directly in the Laplace domain, where the circuit components are replaced by their impedances observed as transfer functions. The Laplace transform has paramount importance in studying the displacement in various dynamical systems (mechanical vibration). 5.2 Application to Electrical Circuits 5.2.1 The Scheme for Solving Electrical Circuits The scheme for solving electrical circuits is outlined below. Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Electrical Circuits and Mechanical Systems 391 Step 1: Apply Kirchhoff’s laws to the given circuit, which yields linear ordinary differential equations with constant coefficients. Step 2: Take the Laplace equation to transform both sides of the equation. A differential equation with constant coefficients is transformed into an algebraic equation. Step 3: Use the properties of the Laplace transform and the initial conditions and simplify the algebraic equation obtained for L ^i t ` in the S domain. I s Step 4: A table of transforms, rather than the inversion integral of (2.2), is used to find the inverse transform. Step 5: In general, a partial-fraction expansion is required to expand complicated functions of s into the simpler functions available in Laplace transform tables. Step 6: Find the inverse transform of I s to obtain i t , the solution of the differential equation is the required output of the circuit (voltage and current). LEARNING OBJECTIVES On reaching the end of the chapter, we expect you to have understood and be able to apply the following: x To explore the procedure for solving a complete electrical circuit using the Laplace transform technique. x The use of the Laplace transform technique to obtain the desired response of an electrical system. Chapter 5 392 x How to determine the transfer function and the impulse and step response of an electrical system. x To know the relation between the input and the output in the S domain using the transfer function and can use it to calculate the displacement of a mechanical system. Example 5.1. Use the Laplace transform technique to find the current in the RC-circuit shown in Figure 5.1a. Suppose an impulse voltage G t is applied as an input shown in Figure 5.1b. The circuit is assumed to be quiescent before the input is applied. C t R Figure 5.1a Figure 5.1b Solution: Applying KVL to loop Figure 5.1a, we get t 1 R i t ³ i W dW C0 G t Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Electrical Circuits and Mechanical Systems 393 dq is the current. The two terms on the left give the voltage dt Here, i drop across the resistor and capacitor, respectively. We take Laplace equations to transform both sides of the equation where I s L ^i t ` , RI s 1 I s C s 1 · § ¨R ¸I s sC ¹ © 1 1 . This algebraic equation can be solved for I 1 s 1 · R§ ¨s ¸ RC ¹ © I s I s s as ª§ 1 · 1 º s ¨ ¸ « 1 © RC ¹ RC » « » 1 · » R« § s ¸ «¬ ¨© RC ¹ »¼ ­ ½ 1 ° °° 1° RC ®1 ¾ 1 ·° R° § s °¯ ¨© RC ¸¹ °¿ Taking the inverse Laplace transform of I the result s and using Table 2.1 gives Chapter 5 394 1ª 1 RC1 t º G t e » « R¬ RC ¼ i t which is the required current in the RC-circuit. Example 5.2 The L C R a capacitor C circuit consists of a resistor R 1F , and an inductor L 1H connected in series together with a voltage source V at t 2: , 1volts . Before closing the switch 0 , both the charge on the capacitor and current is zero. Determine the charge and current. Solution: We now demonstrate the use of the Laplace transform in solving for the current in an electric circuit. Consider the L C R Figure 5.2, where V series circuit in 1volts R L i + V C – Figure 5.2 Applying KVL to the above circuit, the integro-differential equation that characterizes the electrical system is Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Electrical Circuits and Mechanical Systems 395 t di 1 Ri t L ³ i W d W dt C 0 V d 2q dq q L 2 R V dt dt C . Here, q represents the electrical charge and i dq represents the dt current. The three terms on the left give the voltage drop across the inductor, resistor, and capacitor, respectively. Substituting the given values for the resistance, inductance, and capacitance gives d 2q dq 2 q 1 2 dt dt . Because of the linearity of the equation and the Laplace transform operation, taking the Laplace transform of the differential equation, we have 1 s s 2 2 s 1 L ^q t ` . ^ This algebraic equation can be solved for L q t L ^q t ` 1 s s 1 2 . ` as Chapter 5 396 s is the desired current i t , t ! 0 The inverse Laplace transform of I ^ However, L q t ` is not given in Table 2.1. In cases such as this, we use partial fraction expansions to express a Laplace transform as a sum of ^ simpler terms in the table. We can express L q t L ª¬ q t º¼ A B C 2 s s 1 s 1 L ^q t ` 1 1 1 2 s s 1 s 1 ` as . Applying the inverse Laplace transform to the above equation, and using the linearity of the inverse Laplace transform, results in q t 1 e t te t . Thus, the current i t , t ! 0 is i t dq et tet et tet dt . Example 5.3. An inductor of L 1 henrys and a capacitor of C farads are connected in series with a generator of V the charge q as a function of time if V t ­0 0 d t 1 . ® ¯V0 t t 1 q 0 1 t volts. Find 0 i 0 , and Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Electrical Circuits and Mechanical Systems 397 Solution: The differential equation that characterizes the electrical system is L d 2q t dt 2 1 q t C V0 u t 1 . Because of the linearity of the equation and the Laplace transform operation, taking the Laplace transform of the differential equation, we have ­° d 2 q t L® q t 2 dt ¯° ½° ¾ V0 L ^ u t 1 ` ¿° . Using the derivative property and all initial conditions being zero gives s2 1 Q s Q s V0 e s s V0 e s s s2 1 . We expand this S domain solution into partial fractions as Q s ª1 º s » V0 e s « 2 s 1 »¼ «¬ s . Applying the inverse Laplace transform to the above equation, and using its linearity, results in q t V0 1 cos t 1 u t 1 . Chapter 5 398 Example 5.4. The differential equation for the current i t in an LR circuit is Ri t L di t E t . dt Find the current in an LR circuit if the initial current is i t given that L 4: , and E t 2H , R 0A 2e 5t with time t measured in seconds. Solution: L di t dt Ri t E t . Here, i dq is the current. The two terms on the left give the voltage dt drop across the inductor and resistor, respectively. Substituting the given values for the resistance and inductance gives di t dt 2i t e 5t . Taking the Laplace transform in the usual way and using i 0 gives s 2 L ^i t ` 1 s5 . ^ ` as This algebraic equation can be solved for L i t 0A Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Electrical Circuits and Mechanical Systems L ^i t ` 399 1 s2 s5 . Resolving into partial fractions gives L ^i t ` A B s2 s5 L ^i t ` 1§ 1 1 · ¨¨ ¸ 3© s2 s 5 ¸¹ . Applying the inverse Laplace transform to the above equation, and using its linearity, results in i t 1 2t e e 5t . 3 Example 5.5. The LR circuit consists of a resistor R and an inductor L connected in series together with a voltage source E t . Prior to closing the switch at t 0, the currents are zero. Determine the current. Solution: We now demonstrate the use of the Laplace transform in solving for the current in an electric circuit. Consider the LR circuit in Figure 5.3. Chapter 5 400 Figure 5.3 Applying KVL to the above circuit, the differential equation that characterizes the electrical system is Ri t L di t dt E t . dq is the current. The two terms on the left give the voltage dt Here, i drop across the resistor and inductor, respectively di t dt R i t L E t L . Taking the Laplace transform in the usual way and using i 0 gives R· § ¨ s ¸ L ^i t ` L¹ © E Ls 0A Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Electrical Circuits and Mechanical Systems 401 ^ ` as This algebraic equation can be solved for L i t L ^i t ` E R· § Ls ¨ s ¸ L¹. © The inverse Laplace transform of I s is the desired current i t , t ! 0 However, L ^i t ` is not given in Table 2.1. In cases such as this, we use partial fraction expansion to express a Laplace transform ^ ` as as a sum of simpler terms in the table. We can express L i t L ^i t ` L ^i t ` A B R· s § ¨s ¸ L¹ © ª º « » E 1 1 « » R ·» R «s § s ¨ ¸ «¬ L ¹ »¼ . © Applying the inverse Laplace transform to the above equation, and using its linearity, results in i t E ª RL t º 1 e »¼ R «¬ . Chapter 5 402 Example 5.6. The LR circuit consists of a resistor R and an inductor L connected in series together with a voltage source Ee at . Prior to closing the switch at t 0 , the currents are zero. Determine the current i t . Solution: We now demonstrate the use of the Laplace transforms in solving for the current in an electric circuit. Consider the LR circuit in Figure 5.4 with the voltage source Ee at . Figure 5.4 By applying KVL we arrive at the following differential equation Ri t L Here, i di t dt Ee at . dq is the current. The two terms on the left give the voltage dt drop across the resistor and inductor, respectively Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Electrical Circuits and Mechanical Systems di t R i t dt L 403 E at e L . Taking the Laplace transform in the usual way, and using i 0 0A , gives L ^i t ` E R· § L sa ¨s ¸ L¹. © The inverse Laplace transform of I s is the desired current I t , t ! 0. However, the transform for L ^i t ` is not given in Table 2.1. In cases such as this, we use partial fraction expansion to express a Laplace transform as a sum of simpler terms in the table. We can express L ^i t ` as L ^i t ` L ^i t ` A B R· sa § ¨s ¸ L¹ © ª º « » E 1 1 « » R ·» R aL « s a § ¨s ¸» «¬ L ¹¼ . © Applying the inverse Laplace transform to the above equation, and using its linearity, results in Chapter 5 404 i t R tº ª at E L «e e » R aL ¬ ¼ . Example 5.7. The series LRC circuit shown in Figure 5.5 consists of C 5: L 1H . 0.25 F R Use the Laplace transform technique. R + Vm C ~ – VC i(t) L Figure 5.5 a Determine the differential equation relating Vin to Vc . b Obtain Vc for Vin e t with Vc 0 1 and Vc' 0 2. Solution: a By applying KVL we arrive at the following differential equation t di t 1 ³ i W dW Vin Ri t L dt C 0 It is known that i rewritten as C . dVc , hence the above differential equation can be dt Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Electrical Circuits and Mechanical Systems 405 d 2VC dV LC 2 R C C VC Vin dt dt . Substituting the given values for the resistance, inductance, and capacitance gives d 2VC dV 5 C 4VC 4Vin 2 dt dt b Given d 2VC dV Vin , 2 5 C 4VC 4e t u t dt dt . In this instance, the forcing function is the step function u t above equation. This function is discontinuous at t of the 0 and, therefore, is not the solution of any linear homogeneous differential equation with constant coefficients. This example of an initial value problem that we cannot solve easily uses undetermined coefficients. The advantage of the Laplace transform method is that the solution of the above initial value problem can be obtained with one application of the method. Taking the Laplace equation to transform both sides and using the initial conditions Vc 0 1 and Vc' 0 2. s 2 5s 4 L ª¬VC t º¼ s 2 5 s 2 5s 4 L ª¬VC t º¼ 4 s 1 4 s7 s 1 Chapter 5 406 s 2 5s 4 L ª¬VC t º¼ s 2 8s 11 s 1 . ^ This algebraic equation can be solved for L VC t ` as s 2 8s 11 s 1 s 2 5s 4 L ª¬VC t º¼ s 2 8s 11 L ª¬VC t º¼ s 4 s 1 2 . The inverse Laplace transform of L ^VC t ` is the desired voltage VC t . However, the transform for L ^VC t ` is not given in Table 2.1. In cases such as this, we use partial fraction expansion to express a Laplace transform as a sum of simpler terms in the table. ^ Expanding L Vc L ª¬VC t º¼ t ` using partial fraction expansion s 2 8s 11 s 4 s 1 A B C 2 s4 s 1 s 1 2 Solving for A, B, and C, we obtain A Thus, 5 ,B 9 14 and C 9 2 . 3 . Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Electrical Circuits and Mechanical Systems L ª¬VC t º¼ 407 5 ­ ° 1 ½ ° 14 ­ ° 1 ½ ° 2­ ° 1 ½ ° ® ¾ ® ¾ ® 2 ¾ 9 ¯ 4 9 1 3 s s ° ° ° ° ° ¿ ¯ ¿ ¯ s 1 ° ¿. Applying the inverse Laplace transform to the above equation, and using its linearity, results in VC t 5 4t 14 t 2 t e e te . 9 9 3 Example 5.8. An electromagnetic field (EMF) of applied to an V EG t is LCR series circuit. Determine the charge on the capacitor and the resulting current in the circuit at time t; initially there is no current in the circuit and no charge on the condenser. Solution: We now demonstrate the use of Laplace transforms in solving for the current in an electric circuit. Consider the LCR series circuit in Figure 5.6, where V EG t . R L i + V – Figure 5.6 C Chapter 5 408 Applying KVL to the above circuit, the integro-differential equation that characterizes the electrical system is Ri t L L di t dt t 1 i W dW V C ³0 d 2q dq q R V 2 dt dt C Here, § ¨ i © dq · ¸ dt ¹ . q represents the electrical charge and i dq dt represents the current. The three terms on the left give the voltage drop across the inductor, resistor, and capacitor, respectively. d 2q dq q L 2 R EG t dt dt C d 2 q R dq q dt 2 L dt LC E G t L . Because of the linearity of the equation and of the Laplace transform operation, taking the Laplace transform of the differential equation, we have 1 · § 2 R ¨s s ¸ L ^q t ` L LC ¹ © E L . ^ The algebraic equation can be solved for L q t ` as Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Electrical Circuits and Mechanical Systems E 1 1 · L§ 2 R ¨s s ¸ L LC ¹ © L ^q t ` L ^q t ` 409 ª E« 1 L « s O 2 p2 «¬ º » » »¼ where O § 1 R R2 · 2¸ & p2 ¨ 2L © LC 4 L ¹ . Taking the inverse Laplace transform, we get E Ot ªe sin pt º¼ Lp ¬ . q t Thus, dq dt i t E Ot ªe p cos pt O sin pt º¼ . Lp ¬ Example 5.9. An inductor of L 1 henrys and a capacitor of C 1 farads are connected in series with a generator of V the charge q as a function of time if q 0 t volts. Find 0 i 0 ­0 0 d t 1 . ® ¯1 t t 1 V t Solution: The differential equation that characterizes the electrical system is L d 2q t dt 2 1 q t C V t . and Chapter 5 410 The two terms on the left give the voltage drop across the inductor, and capacitor, respectively. d 2q t dt 2 q t u t 1 . Assuming that the Laplace transform of the solution Y s exists, and using the fact that L is a linear operator, we take the Laplace transform of the above differential equation and write 2 °­ d q t L® q t 2 °¯ dt °½ ¾ L^ u t 1 °¿ L ª¬ q '' t º¼ L ª¬ q t º¼ 2 s 1 Q s ` e s s e s s Q s e s s s2 1 Q s §1 · s ¸ e s ¨ 2 ¨s ¸ s 1 © ¹. Now that we have obtained the partial fraction expansion. Taking the inverse Laplace transform of each term on the right, and using the linearity property of the Laplace transform, we find that Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Electrical Circuits and Mechanical Systems q t 411 ­ §1 s · ½° ° ¸¾ L1 ®e s ¨ 2 ¨ ¸ s s 1 °¯ © ¹ °¿ Finally, using the transform pairs established in table 2.1, we have q t 1 cos t 1 u t 1 . Example 5.10 A 20-volt battery is applied to an L C R series circuit with an inductance of L and resistance of R 1H capacitance of C 104 F , 160:. Determine the charge on the capacitor and the resulting current in the circuit at time t; initially there is no current in the circuit and no charge on the condenser. Solution: We now demonstrate the use of Laplace transforms in solving for the current in an electric circuit. Consider the L C R series circuit in Figure 5.6, where V 20 Volts. R L i + V – Figure 5.7 C Chapter 5 412 Applying KVL to the above circuit, the integro-differential equation that characterizes the electrical system is Ri t L di t dt t 1 i W dW V C ³0 . The charge q on the LCR circuit is determined by L d 2q dq q R V dt 2 dt C § ¨ i © dq · ¸ dt ¹ . Here, q represents the electrical charge and i dq represents the dt current. The three terms on the left give the voltage drop across the inductor, resistor, and capacitor, respectively. Substituting the given values for the resistance, inductance, and capacitance gives d 2q dq 160 104 q 20 2 dt dt D 2 160 D 104 q 20 . Because of the linearity of the equation and the Laplace transform operation, taking the Laplace transform of the differential equation, we have s 2 160 s 104 L ^q t ` 20 s . Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Electrical Circuits and Mechanical Systems ^ This algebraic equation can be solved for L q t 20 s s 160 s 104 L ª¬ q t º¼ 413 ` as 2 . The inverse Laplace transform of I ^ However, L q t s is the desired current i t , t ! 0. ` is not given in Table 2.1. In cases such as this, we use partial fraction expansion to express a Laplace transform as a sum of ^ simpler terms in the table. We can express L q t L ^q t ` A Bs c 2 s s 160 s 104 L ^q t ` º 1 ª1 s 160 « 2 » 500 « s s 160s 104 » ¬ ¼ L ^q t ` 1 ª1 s 80 80 º « 2 » 500 « s s 160s 104 » ¬ ¼ ª 1 «1 500 « s ¬« s 80 s 80 2 602 80 ` as º » 2 s 80 602 »» ¼. 1 Applying the inverse Laplace transform to the above equation, and using its linearity, results in Chapter 5 414 1 ª 4 § ·º 1 e 80t ¨ cos 60 t sin 60 t ¸ » « 500 ¬ 3 © ¹¼ . q t The resulting current i t in the circuit is given by i t 1 80t ªe sin 60 t º¼ 3¬ . Example 5.11. The differential equation for the current i t in an LR circuit is Ri t L dR dt V t with L 1H , R 4: and a voltage source (in volts) V t ­2 ® ¯0 0 t 1 t t1 . a Find the current i t if i 0 0. b Compute the current at t 1.5 seconds, i.e. compute i 1.5 . c Evaluate lim ^i t ` . t of Solution: a Since V t circuit is 2 2u t 1 , the differential equation of the LR Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Electrical Circuits and Mechanical Systems di t dt 4i t 415 2 2u t 1 . Taking the Laplace transform in the usual way gives s 4 s L ^i t ` 2 2e s s s . ^ ` gives Solving for L i t L ª¬i t º¼ 2 2e s . s s4 s s4 Let G s 2 s s4 , using partial fractions, we obtain G s 1 ª1 1 « 2 ¬s s4 º » ¼ . Applying the inverse Laplace transform to the above equation, and using its linearity, results in g t 1 1 e 4t 2 since L ª¬i t º¼ G s e sG s , Chapter 5 416 we can take the inverse Laplace to transform to get the current 1 1 ª¬1 e 4t º¼ ª1 e 4 t 1 º u t 1 . ¼ 2 2¬ i t b We can express i t as follows ­1 1 e 4t ° °2 ® ° 1 e 4 t 1 e 4t °̄ 2 i t For t 0 t 1 t t1 1.5, we get i 1.5 1 4 1.51 e e 4 1.5 2 0.0664. c For t t 1, we have i t 1 4 t 1 e e 4t 2 . Therefore, ª1 º lim ª¬i t º¼ lim « e4 t 1 e4t » 0. t of t of 2 ¬ ¼ Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Electrical Circuits and Mechanical Systems 417 Example 5.12. Consider the following parallel RL circuit shown in 1H , R 1: . Figure 5.8 with L a Determine the differential equation relating I s and I L . b IL t using the Laplace c Obtain the zero-input response for I L t using the Laplace Obtain the zero-state response for transform for e 5t . Is t transform with I L 0 1. Figure 5.8 Solution: a I s and I L are related by the following differential equation IL IR. IS dI L t dt IL t Is t . Chapter 5 418 b For the given I s , dI L t dt IL t e5t . Taking the Laplace transform in the usual way gives 1 s5 sL ^ I L t ` I L 0 L ^ I L t ` since I L 0 0 for zero states, s 1 L ^I L t ` 1 s5 L ^I L t ` 1 s 1 s 5 . L ^ I L t ` is the desired current The inverse Laplace transform of I L t . However, L ^ I L t ` is not given in Table 2.1. In cases such as this, we use partial fraction expansion to express a Laplace transform as a ^ sum of simpler terms in the table. We can express L I L L ^I L t ` 1ª 1 1 º « » s 5 ¼» 4 ¬« s 1 . t ` as Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Electrical Circuits and Mechanical Systems 419 Applying the inverse Laplace transform to the above equation, and using its linearity, results in IL t 1 t e e 5t . 4 c For the zero-input response I s 0 0, and given that I L 0 0, we have to find the solution of the following differential equation for the zero-input response dI L t dt IL t 0, I L 0 1 . Taking the Laplace transform in the usual way gives sL ^ I L t ` 1 L ^ I L t ` 0 s 1 L ^I L t ` 1 . Thus, L ^I L t ` 1 s 1 . ^ The inverse transform of L I L IL t et u t . t ` is the zero-input response given by Chapter 5 420 Example 5.12. Use the Laplace transform technique to find the current in the RC circuit in figures 5.9a and 5.9b, if a single rectangular wave with voltage is applied as an input. The circuit is assumed to be quiescent before the wave is applied. Figure 5.9a Figure 5.9b Solution: The input in terms of a unit step function is given by v t V0 ª¬u t a u t b º¼ with a b. Applying KVL to the above loop, we get t 1 R i t ³ i W dW V0 ª¬u t a u t b º¼ C0 Taking the Laplace transform in the usual way gives . Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Electrical Circuits and Mechanical Systems RI s 1I s C s 421 ª e as ebs º V0 « » s s ¼ ¬ 1 · § ¨R ¸I s sC ¹ © ª e as ebs º V0 « » s s ¼ ¬ ª º as bs « » V0 e e « » 1 · § 1 ·» R «§ s s «¬ ¨© RC ¸¹ ¨© RC ¸¹ »¼ . I s Applying the inverse Laplace transform to the above equation, and using its linearity, results in 1 t b u º V0 ª RC1 t a RC e u t a e u t b « » R¬ ¼ i t . Example 5.13. Use the Laplace transform technique to find the current through the resistance to the circuit shown in Figure 5.10 with L 2H , C 50 P F , R 100: and V t sin 100t . There is no current flowing in either loop prior to closing the switch at time t 0. Chapter 5 422 C i2 t=0 + i1 L V R – Figure 5.10 Solution: Applying Kirchhoff’s second law to each of the two loops in turn gives Loop-1: 1 ª di di º i1 dt L « 1 2 » V ³ C ¬ dt dt ¼ . Substituting the given values for the inductance and capacitance gives 1 ª di di º i dt 2 « 1 2 » sin 100t 6 ³ 1 50 u10 ¬ dt dt ¼ . Taking the Laplace equation to transform both sides of the equation where I1 s L ^i1 t ` & I 2 s L ^i2 t ` , 2 u 106 I1 s 2 sI1 s 2 sI 2 s s 100 s 1002 2 Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Electrical Circuits and Mechanical Systems 423 s 50 2 s 1002 s 2 104 I1 s s 2 I 2 s (5.1) Loop-2: ª di di º R2i2 L « 2 1 » 0 ¬ dt dt ¼ . Substituting the given values for the inductance and capacitance gives ª di di º 100i2 L « 2 1 » 0 ¬ dt dt ¼ . Taking the Laplace equation to transform both sides of the equation where I1 s L ^i1 t ` & I 2 s L ^i2 t ` , 100 I 2 s 2sI 2 s 2sI1 s sI1 s s 50 I 2 s 0 0 (5.2) Solving (5.1) and (5.2), we get I1 s ª º s s 50 « » 2 « s 100 s 2 104 » ¬ ¼ I2 s ª º s2 « » 2 « s 100 s 2 104 » ¬ ¼ . Chapter 5 424 We need to find the inverse Laplace transform of this function of s and we expand using partial fractions, giving I2 s ª º s2 « » 2 « s 100 s 2 104 » ¬ ¼ I2 s ª§ 1 · º 1 1 s §1· § 1 · «¨ » ¨ ¸ ¸ ¨ ¸ 2 © 200 ¹ s 2 104 »¼ «¬© 200 ¹ s 100 © 2 ¹ s 100 ª A « s 100 ¬« B s 100 2 Cs D º » s 2 104 ¼» . The current through the resistance i2 i2 t t is ª§ 1 · 100t § t · 100t § 1 · 4 º ¨ ¸e ¨ ¸ cos 10 t » . «¨ 200 ¸ e ¹ ©2¹ © 200 ¹ ¬© ¼ Example 5.14. Use the Laplace transform technique to find the current through the capacitance to the circuit shown in Figure 5.11 with R1 1: R2 , L1 1H L2 , C 1F & V 10V . There is no charge on the capacitors and no current flowing in the inductances prior to closing the switch at time t Figure 5.11 0. Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Electrical Circuits and Mechanical Systems 425 Solution: Applying Kirchhoff’s second law to each of the two loops in turn gives Loop-1: R i1 i2 L d 1 i1 i2 ³ i1 dt dt C V . Substituting the given values for the inductance and capacitance gives i1 i2 d i1 i2 ³ i1 dt dt 10 . Taking the Laplace transform, where I1 s L ^i1 t ` & I 2 s L ^i2 t ` , 1 I1 s I 2 s s I1 s I 2 s I1 s s I s s 1 I1 s s 1 I 2 s 1 s 10 s 10 s (5.3) Loop-2: R2i2 L di2 1 i1 t dt C ³ 0 . Substituting the given values for the inductances and capacitance gives i2 di2 i1 t dt ³ 0 Taking the Laplace transform, where Chapter 5 426 I1 s L ^i2 t ` , L ^i1 t ` & I 2 s I s I 2 s sI 2 s 1 s 0 (5.4) Solving (5.3) and (5.4), we get I1 s I1 s ª º 10 « 2 » & I2 s «¬ s s 2 »¼ ª º 10 « » «¬ s s 1 s 2 s 2 »¼ ª º 10 « 2 » I1 s «¬ s s 2 ¼» ª º « » « » 10 « » « § § 1 ·2 § 7 ·2 · » «¨¨ s ¸ ¨ ¸ ¸» ¨ 2 2 © ¹ « © ¹ ¸¹ »¼ ¬© . The current through the capacitance i1 t is i1 t ª§ 20 · §¨ 12 ·¸t § 7 ·º © ¹ t ¸¸ » . sin ¨¨ «¨ ¸e 2 7 © ¹ © ¹ ¼» ¬« Example 5.15. Use the Laplace transform technique to find the loop currents shown in Figure 5.12 with R1 1: , R1 1.4:, L1 1H and L2 V t § § 1 ·· 100 ¨ u t u ¨ t ¸ ¸ . © 2 ¹¹ © 0.8 H and Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Electrical Circuits and Mechanical Systems L1 L2 i2 i1 427 R2 R1 V Figure 5.12 Applying KVL to loop-1 with current i1 t , and substituting the given values for the resistance and inductance, gives 0.8 ª di1 § 1 ·º 1 i1 i2 1.4 i1 100 «u t u ¨ t ¸ » dt © 2 ¹¼ ¬ ª di1 § 1 ·º 3 i1 1.25i2 125 «u t u ¨ t ¸ » dt © 2 ¹¼ . ¬ Applying KVL to loop-2 with current i2 t , and substituting the given values for the resistance and inductance, gives 1 di2 1 i2 i1 dt di2 i1 i2 dt 0 0 . Chapter 5 428 Taking the ^i 0 0 i2 0 ` , we get 1 Laplace transform, s º ª 2 1 e » 125 « «s s » ¬« ¼» s 3 I1 s 1.25I 2 s I1 s s 1 I 2 s Solving for I1 I1 s I2 s s assuming 0 and I 2 s s 125 s 1 § · ¨1 e 2 ¸ § 1 ·§ 7 · ¹ s ¨ s ¸¨ s ¸ © © 2 ¹© 2 ¹ s § · 125 2 1 e ¨ ¸ § 1 ·§ 7 · ¹ s ¨ s ¸¨ s ¸ © 2 2 © ¹© ¹ . Using partial fractions, we get 125 s 1 1 ·§ 7· § s¨ s ¸¨ s ¸ 2 ¹© 2¹ © A B C 1· § 7· s § ¨s ¸ ¨s ¸ 2¹ © 2¹ © the initial conditions Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Electrical Circuits and Mechanical Systems ª º « 125 s 1 » » A « « § s 1 ·§ s 7 · » ¸ «¬ ¨© 2 ¸¨ ¹© 2 ¹ »¼ s 0 ,B ª º «125 s 1 » « » « s§s 7 · » ¸ «¬ ¨© 2 ¹ »¼ s 1 429 500 7 125 ,C 3 2 ª º «125 s 1 » « » « s§s 1 · » ¸ «¬ ¨© 2 ¹ »¼ s 7 625 21 2 s s s · · · 500 § 250 § 625 § 2 2 ¨1 e ¸ ¨1 e ¸ ¨1 e 2 ¸ 7s © ¹ 3§ s 1 · © ¹ 21§ s 7 · © ¹ ¨ ¸ ¨ ¸ 2¹ 2¹ © © I1 s . Similarly I2 s s s s · · · 500 § 250 § 250 § 2 2 2 1 1 1 e e e ¨ ¸ ¨ ¸ ¨ ¸ 7s © ¹ 3§ s 1 · © ¹ 21§ s 7 · © ¹ ¨ ¸ ¨ ¸ 2¹ 2¹ © © . Applying the inverse Laplace transform to the above equations, and using its linearity, results in i1 t 125 2t 625 72t 500 e e 3 21 7 i2 t 250 2t 250 72t 500 e e 3 21 7 Chapter 5 430 5.3 Application to Mass-spring-damper Mechanical System Suppose a mass m is hung on an idealized spring whose upper end is supported rigidly. This is an idealized spring with negligible mass and with its restoring force proportional to its extension. Let 0, the origin, be the equilibrium position and the y t coordinate with downward displacement being positive and upward negative. Suppose that the load is pulled downward at a distance y t by force F t . By Hooke’s law F ky t where k is a constant called the force constant of the spring. By Newton’s second law m d2y t k y t dt 2 . Finally, assume that a damping force proportional to the velocity is present, where the damping force is D dy t dt , Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Electrical Circuits and Mechanical Systems 431 which is a fairly accurate assumption for small velocities. This is the fundamental equation of damped simple harmonic motion m d2y t dt 2 D dy t dt k y t 0. In every oscillatory system, the oscillations cannot be maintained indefinitely due to the gradual dissipation of mechanical energy, unless energy is supplied to the system. If an external force F t is applied, the equation becomes m d2y t dt 2 D dy t dt k y t F t . Such cases are called forced oscillations. The following example shows how to use the Laplace transform method to obtain the displacement of mechanical systems described by a linear differential equation with constant coefficients. Chapter 5 432 Example 5.16. Use the Laplace transform technique to find the displacement of mechanical systems shown in Figure 5.13 with spring constant k 25 , damping constant D 6, external force F t mass M 1 and 4sin 2t. K=4 D=2 M=1 y(t) F(t) = sin 2t Figure 5.13 Solution: A mass–spring–damper system can be modeled using Newton’s law and Hooke’s law (using Table 3.2). The governing equation representing the above system is given by d2y t dt 2 2 dy t dt 4y t sin 2t . Assuming that the Laplace transform of the solution Y s exists, and using the fact that L is a linear operator, we take the Laplace transform of the above differential equation and write Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Electrical Circuits and Mechanical Systems 433 2 dy t °­ d y t °½ L® 2 4 y t ¾ L ^sin 2t` 2 dt ¯° dt ¿° L ª¬ y '' t º¼ 2 L ª¬ y ' t º¼ 4 L ª¬ y t º¼ 2 s 4 2 ª¬ s 2Y s sy 0 y ' 0 º¼ 2 ª¬ sY s y 0 º¼ 4Y s It is now necessary to invert Y 2 s 4 2 s . To accomplish this, some algebraic manipulation is necessary if we are to identify the terms on the right with the entries in Table 2.1. When expressed in terms of partial fractions, after a little manipulation, Y Y s s becomes 2 s 2s 4 s 2 4 2 . Using partial fractions, we can write this as Y s 2 2 s 2s 4 s 2 4 2 As B Cs D 2 s 2s 4 s 4 2 As B s 2 4 Cs D s 2 2 s 4 Hence, comparing the coefficients of both sides we get s3 : A C 0, s2 : D B 0, Chapter 5 434 s: 2 D 4C 1: 4B 4D 2 . 0, By these equations, we obtain 1 ,B 2 A 1 and D 4 1 ,C 4 0. Hence, we have 1 2 s 1 4 Y s 2 s 2s 4 14 s s2 4 Y s 1 °­ 1 s 1 °½ 1 °­ °½ 1 °­ s °½ ® 2 ¾ ® 2 ¾ ® ¾ 4 ° s 2s 4 ° 4 ° s 2s 4 ° 4 ° s 2 4 ° ¯ ¿ ¯ ¿ ¯ ¿ Y s ­ ½ 1° 1 1 ­° s ½° ° 1 ­° s 1 ½° ® ¾ ® ¾ ® ¾ 4 ° s 1 2 3 ° 4 ° s 1 2 3° 4 ° s2 4 ° ¯ ¿ ¯ ¿ ¯ ¿ . Applying the inverse Laplace transform to the above equation, and using its linearity, results in 1 y t 4 3 e t sin 1 3 t e t cos 4 1 3 t cos 2t . 4 Example 5.17. The differential equation for a mass-spring system is m d 2x t dt 2 D dx t dt K x t f t . Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Electrical Circuits and Mechanical Systems Consider a mass-spring system with mass m a spring with constant K 1kg that is attached to 5 N / m. The medium offers a damping force six times the instantaneous velocity, i.e. D 6 N . s / m. a Determine the position of the mass x t initial conditions: x 0 435 3, x ' 0 D 6 N .s / m. if it is released with 1. There is no external force. b Determine the position of the mass x t if it is released with the initial conditions: x 0 external force f t 0 x ' 0 , and the system is driven by an 30 sin 2t in Newtons with time t measured in seconds. Solution: a The initial-value problem for the position of the mass is d 2x t dt 2 6 We have f dx t t dt 5x t f t . 0 the initial conditions are x 0 3, x ' 0 1. Taking the Laplace transform on both sides of the differential equation, we get 2 ­ dx t ½ °­ d x t °½ L® ¾ 6L ® ¾ 5 L ^x t ` 0 2 dt °¯ dt °¿ ¯ ¿ Chapter 5 436 s 2 6 s 5 ^ x t ` 3s 19 . This algebraic equation can be solved for L L ^x t ` ^ x t ` as 3s 19 . s 1 s 5 The inverse Laplace transform of L ^ x t ` is the desired displacement x t , t ! 0 However, the transform for L ^ x t ` is not given in Table 2.1. In cases such as this, we use partial fraction expansion to express a Laplace transform as the sum of simpler terms in the table. We can express L ^ x t ` as L ^x t ` 4 1 s 1 s5 . Taking the inverse Laplace transform of L 4e t e 5t . gives the result x t b We have f t x 0 0 and x ' 0 0. d 2x t dt 2 6 dx t dt ^ x t ` and using Table 2.1 5x t 30 sin 2t and the initial conditions are 30sin 2t . Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Electrical Circuits and Mechanical Systems 437 Taking the Laplace transform on both sides of the differential equation, we get ­° d 2 x t ½° ­ dx t ½ L® ¾ 6L ® ¾ 5 L ^ x t ` 30 L ^sin 2t` 2 dt °¯ dt °¿ ¯ ¿ s 2 6s 5 ^ x t ` 60 s 4 2 This algebraic equation can be solved for L 60 s 1 s 5 s2 4 L ^x t ` The inverse Laplace transform of L ^ x t ` as . ^ x t ` is the desired displacement x t , t ! 0 However, the transform for L ^ x t ` is not given in Table 2.1. In cases such as this, we use partial fraction expansion to express a Laplace transform as the sum of simpler terms in the table. We can express L ^ x t ` as L ^x t ` ­ 1 ½ 72 ° ­ ½ ­ s ° 1 ½ ° 15 « 1 » 12 ° ° ° 3® « » ¾ ® 2 ¾ ® 2 ¾ ° ° s 4 ¿ ° 29 ¯ ° s 4 ¿ ° ¯ s 1 ° ¿ 29 ¬« s 5 ¼» 29 ¯ . Applying the inverse Laplace transform to the above equation, and using its linearity, results in Chapter 5 438 3et x t 15 5t 12 72 e sin 2t cos 2t 29 29 u 2 29 thus, 3et x t 15 5t 6 72 e sin 2t cos 2t. 29 29 29 Example 5.18. An 8 lb weight is attached to a spring with a spring constant equal to 4lb / ft. Neglecting damping, the weight is released from rest at 4 ft below the equilibrium position. At t 2sec, it is struck with a hammer, providing an impulse of 5lb sec. Determine the displacement function y t of the weight. Solution: This situation mass-spring system can be modeled using Newton’s law and Hooke’s law (using Table 3.2). The governing equation representing to the above system is given by 2 8 d y t 4y t 32 dt 2 5G t 2 along with the initial conditions y 0 d2y t dt 2 16 y t 4, y ' 0 0. 20G t 2 Assuming that the Laplace transform of the solution Y s exists, and using the fact that L is a linear operator, we take the Laplace transform of the above differential equation and write Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Electrical Circuits and Mechanical Systems 2 °­ d y t 16 y t L® 2 °¯ dt 439 °½ ¾ 20 L ^G t 2 ` °¿ L ª¬ y '' t º¼ 16 L ª¬ y t º¼ 20e 2 s ª¬ s 2Y s sy 0 y ' 0 º¼ 16Y s 20e 2 s . Imposing the initial conditions, we obtain the Laplace transform of the solution as s 2 16 Y s Y s 20e 2 s 3s e 2 s s 20 2 3 2 s 16 s 16 . Applying the inverse Laplace transform to the above equation, and using its linearity, results in y t 5sin 4 t 2 u t 2 3cos 4t . Example 5.19 A 2 kg mass is suspended from a spring with constant 512 N / m. It is set in motion by pulling it 10 cm above its equilibrium position and then releasing it. A sinusoidal force A sin 8t acts on the mass, but only for t ! 1. Find the position of the mass as a function of time with negligible damping. Solution: The initial-value problem for displacement is Chapter 5 440 2 d 2x t dt 2 512 x t A sin 8t u t 1 x 0 1 ' ,x 0 10 0. If we take the Laplace transform, 2 °­ d x t °½ 2L ® ¾ 512 L ^ x t ` A L ^sin 8t u t 1 ` 2 °¯ dt °¿ s · § 2 ¨ s 2 L ª¬ x t º¼ ¸ 512 L ª¬ x t º¼ 10 ¹ © AL ª¬sin 8t u t 1 º¼ s · § 2 ¨ s 2 L ª¬ x t º¼ ¸ 512 L ª¬ x t º¼ 10 ¹ © AL ª¬sin 8t u t 1 º¼ . Using the second shifting theorem s 2 256 L ª¬ x t º¼ s A s e L ª¬sin 8 t 1 º¼ 10 2 s 2 256 L ª¬ x t º¼ s A s e ^cos8 L >sin 8t @ sin 8 L > cos8t @` 10 2 s 2 256 L ª¬ x t º¼ ­ ½ s A 8 s ° ° e s ®cos 8 2 sin 8 2 ¾ 10 2 s 64 s 64 ¿ ° ° ¯ . Hence, L ª¬ x t º¼ ½° s A s ­° 8 s e cos8 sin 8 ® ¾ s 2 256 s 2 64 s 2 256 s 2 64 ¿° 10 s 2 256 2 ¯° Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Electrical Circuits and Mechanical Systems xt 441 ª º ª º ½° 1 1 ª s º A ­° 1 s 1 » ®8cos8 L1 «e s 2 » « »¾ L « 2 sin8 L 2 2 2 10 « s 256 » 2 ° s 256 s 64 s 256 s 64 « » « »¼ ° ¬ ¼ ¯ ¬ ¼ ¬ ¿ Taking the inverse Laplace transform of L ^ x t ` and using Table 2.1 gives us the result x t 1 A ­ 1 ½ cos16t ®cos8 sin 8 t 1 sin 8cos8 t 1 cos8 sin16 t 1 sin 8cos16 t 1 ¾ u t 1 10 384 ¯ 2 ¿ Example 5.20 A 100 g mass is suspended from a spring with constant 50 N / min . It is set in motion by raising it 10 cm above its equilibrium position and giving it a velocity of 1 m/s downward. During the subsequent motion, a damping force acts on the mass and the magnitude of this force is twice the velocity of the mass. If an impulse force of magnitude 2 N . is applied vertically upward to the mass at t 3sec, find the position of the mass for all time. Solution: The initial-value problem for the position of the mass is 2 dx t 1 d x t 2 50 x t 2 10 dt dt 2G t 3 , x 0 1 ' ,x 0 10 1. If we multiply the differential equation by 10, and take the Laplace transform ­° d 2 x t ½° ­ dx t ½ L® ¾ 20 L ® ¾ 500 L ^ x t ` 20 L ^G t 3 ` 2 dt °¯ dt °¿ ¯ ¿ Chapter 5 442 20e 3 s s 10 1 s 2 20 s 500 L ª¬ x t º¼ L ª¬ x t º¼ L ª¬ x t º¼ s 10 1 20e 3s s 2 20 s 500 s 2 20 s 500 20e 3 s 2 s 10 20 2 1 10 s 10 2 s 10 202 Taking the inverse Laplace transform of L . ^ x t ` and using Table 2.1 gives us the result ª º s 10 « » L « s 10 2 202 » «¬ »¼ 1 § 1 s e 10t L ¨ 2 ¨ s 202 © e 10 t 3 sin 20 t 3 u t 3 x t · ¸ ¸ ¹ e 10t cos 20t , 1 10t e cos 20t. 10 Example 5.21. A mass attached to a spring is released from rest 1 m below the system’s equilibrium position and begins to vibrate. After 2S seconds, the mass is struck by a hammer exerting an impulse on the mass. The system is governed by the differential equation for a mass-spring system, which is d 2x t dt 2 16 x t 5G t 2S and x 0 1 & x' 0 0. Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Electrical Circuits and Mechanical Systems Where x t 443 denotes the displacement from equilibrium at time t. Determine x t . Solution: Taking the Laplace transform on both sides of the differential equation, we get ­° d 2 x t ½° L® ¾ 16 L ^ x t ` 5L ^G t 2S ` 2 ¯° dt ¿° s 2 16 L ^ x t ` 5e 2S s s . Solving for x t gives L ^x t ` e 2S s s 2 5 2 s 16 s 16 . Taking the inverse Laplace transform and using the second shifting theorem, we get x t 5 sin 4 t 2S 4 u t 2S cos 4t . Chapter 5 444 Example 5.22. A mass-spring system with mass 4, damping 8, and spring constant 20 is subject to a hammer blow at time t 0. The blow imparts a total impulse of 1 to the system, which was initially at rest. Find the response y t of the system. Solution: This situation of the mass–spring-damper system can be modeled using Newton’s law and Hooke’s law (using Table 3.2). The governing equation representing the above system is given by 4 d2y t dt 2 8 dy t dt 20 y t G t 0 y' 0 . along with the initial conditions y 0 Assuming that the Laplace transform of the solution Y s exists and using the fact that L is a linear operator, we take the Laplace transform of the above differential equation and write ­° d 2 y t dy t L ®4 8 20 y t 2 dt dt ¯° ½° ¾ L ^G t ` ¿° 4 L ¬ª y '' t ¼º 8 L ¬ª y '' t ¼º 20 L ª¬ y t º¼ 1 4 ª¬ s 2Y s sy 0 y ' 0 º¼ 8 ª¬ sY s y 0 º¼ 20Y s 1 . Imposing the initial conditions, we obtain the Laplace transform of the solution as Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Electrical Circuits and Mechanical Systems 4 s 2 8s 20 Y s Y s 445 1 1 4 s 2s 5 2 1 Y s 2 4 s 1 4 . Applying the inverse Laplace transform to the above equation, and using its linearity, results in y t 1 t e sin 2t. 8 Example 5.23. Motion of a falling body (falling bodies and air resistance). An object falls through the air towards Earth. Assuming that gravity and air resistance are the only forces applied to the object, determine its velocity as a function of time. Newton’s second law states that force is equal to mass times acceleration. We can express this by the equation m dV dt F . Near Earth’s surface, the force of gravity is the same as the object’s weight and is also directed downward. This force can be expressed in mg, where g is the acceleration due to gravity. Air resistance acting on the object is represented by cV , where c is a positive constant depending on the Chapter 5 446 density of the air and the shape of the object. We use the negative sign because air resistance is a force that opposes motion. Applying Newton’s law, we obtain the first-order differential equation m dV dt mg cV with V 0 V0 D Velocity V mg Parachutist Figure 5.14 dV t dt c V t m g with V 0 V0 Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Electrical Circuits and Mechanical Systems 447 Velocity of a parachute We take the Laplace transform equation and get the velocity of a parachute s L ^V t ` V0 c L ^V t ` m c · § ¨ s ¸ L ^V t ` m ¹ © L ^V t ` g s g V0 s g c · § s¨ s ¸ m ¹ © V0 c · § ¨ s ¸ m ¹ . © Resolving into partial fractions gives L ª¬V t º¼ L ª¬V t º¼ V0 A B c · § c · s § ¨ s ¸ ¨ s ¸ m¹ © m¹ © ª º « » V0 g 1 1 « » c ·» § c · mc « s § ¨ s ¸» ¨ s ¸ «¬ m ¹¼ © m ¹. © Taking the inverse Laplace transform, we get V t c c tº t g ª m m «1 e » V0 e . mc ¬ ¼ Chapter 5 448 Example 5.24. The motion of a body falling in a resisting medium may be described by d2y t m dt 2 mg D dy t dt when the retarding force is proportional to the velocity. Find y t 0 y' 0 . for the initial conditions y 0 Solution: Let y '' t D ' y t m g . Taking the Laplace transform of both sides of the given differential equation L ª¬ y '' t º¼ D L ª¬ y ' t º¼ m gL >1@ ^s L ª¬ y t º¼` mD sL ¬ª y t ¼º 2 g s This algebraic equation can be solved for L L ª¬ y t º¼ g D· § s2 ¨ s ¸ m¹. © ^ y t ` as Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Electrical Circuits and Mechanical Systems The inverse Laplace transform of L 449 ^ y t ` is the desired motion of a body y t , t ! 0 However, the transform for L ^ y t ` is not given in Table 2.1. In cases such as this, we use partial fraction expansion to express a Laplace transform as a sum of simpler terms in the table. We can express L ^ y t ` as L ª¬ y t º¼ A B C 2 D· s s § ¨s ¸ m¹ © ­ ½ ° ° m g° 1 ° mg ­ 1 ½ m 2 g ­ 1 ½ ® ¾ ® ¾ ® ¾ D · ° D ¯ s ¿ D2 ¯ s2 ¿ D2 ° § s ¨ ¸ ° m ¹° ¯© ¿ 2 L ª¬ y t º¼ Applying the inverse Laplace transform to the above equation, and using its linearity, results in y t m 2 g mD t mg m 2 g e t. D2 D D2 Another area to which the unit function and impulse function can be applied is studying the deflection of beams, where discontinuous and concentrated loads are encountered. The following example shows how to use the Laplace transform method to obtain the deflection of a beam. Chapter 5 450 Example 5.25. Use the Laplace transform technique to find the lateral deflection y t of the beam shown in Figure 5.15. w W EI, L P l1 P l2 y(t) Figure 5.15 If the loading is non-uniform, the use of the Laplace transform method, in which we make use of the Heaviside unit function and the impulse function, has a distinct advantage. The figure illustrates a uniform beam of length l, freely supported at both ends and bending under a uniformly distributed weight W . Our aim is to determine the transverse deflection y t of the beam. From the elementary theory of beams, we have d4y t d2y t EI P dt 4 dt 2 Where W W t . t is the transverse force per unit length, with a downwards force taken to be positive, and EI is the flexural rigidity of the beam. It is t Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Electrical Circuits and Mechanical Systems 451 assumed that the beam has uniform elastic properties and a uniform crosssection over its length so that both Young’s modulus of elasticity and the moment of inertia I E of the beam about its central axis are constants. Using the Heaviside step function and the Dirac delta function, the force function W t can be expressed as W ª¬1 u t l1 º¼ W ª¬G t l2 º¼ . W t Therefore, equation (1) becomes d4y t d2y t EI P dt 4 dt 2 2 d4y t 2 d y t a dt 4 dt 2 w ª¬1 u t l1 º¼ W ª¬G t l2 º¼ . wˆ ª¬1 u t l1 º¼ Wˆ ª¬G t l2 º¼ . Where a2 P , wˆ EI w and Wˆ EI W . EI Since the left end is hinge support and the right end is sliding support, the boundary conditions are deflection 0 y 0 0. bending moment 0 y '' 0 0. at t 0 Chapter 5 452 at t slope 0 y ' L L 0 y ''' L shear force 0. 0. Applying the Laplace transform, we get L ª¬ y '''' t º¼ a 2 L ª¬ y '' t º¼ wˆ L ª¬1 u t l1 º¼ Wˆ L ª¬G t l2 º¼ . Incorporating the properties and Laplace transforms of the impulse and step functions, we get ^s L ª¬ y t º¼ sy 0 y 0 ` a ^s L ª¬ y t º¼ y 0 ` 4 ' 2 2 2 s s a L ª¬ y t º¼ L ¬ª y t ¼º y' 0 s2 a2 '''' 2 2 ' ª¬1 el1s º¼ Wˆ el2 s wˆ s ª¬1 e l1 s º¼ s y 0 y 0 a y 0 wˆ Wˆ e l2 s s 2 ' '''' 2 ' ª¬1 e l2 s º¼ ª¬ y ''' 0 a 2 y ' 0 ¼º e l1s ˆ ˆ W 2 2 w 3 2 s2 s2 a2 s s a2 s s a2 Taking inverse transforms and making use of the second shift theorem gives the deflection y t as y x ­ y' 0 ½ 1§ 1 · · § t l 1 sin at ¬ª y ''' 0 a 2 y ' 0 ¼º 2 ¨ t sin at ¸ Wˆ ¨ 2 1 3 sin a t l1 ¸ u t l1 ° ° a © a ¹ © a a ¹ ° a ° ® ¾ ° wˆ ª 1 a 2t 2 2 cos at 1 º ­ wˆ ª 1 a 2 t l 2 2 cos a t l 1 º ½ u t l ° 2 2 2 ° »¼ ® «¬ 2a 4 »¼ ¾ ° ¬« 2a 4 ¯ ¿ ¯ ¿ Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: Electrical Circuits and Mechanical Systems To obtain the value of the undetermined constants, we employ y' L the unused 0 and y '' L boundary 453 y ' 0 and y '' 0 , conditions at x L, , i.e. 0. Summary In this chapter, we have described and explained the responses of electrical and mechanical systems using the Laplace transform method. x LTI systems governed by differential equations via electrical circuits with initial conditions have been analyzed by finding the system response. The Laplace transform method’s advantage when forcing functions, such as step and impulse functions, are inputs have been discussed with several examples. x LTI systems governed by differential equations via mechanical systems with initial conditions have been analyzed by finding the system response. The Laplace transform method’s advantage in the solution of simultaneous differential equations obtained via electrical and mechanical systems have also been explained with several examples. CHAPTER 6 APPLICATION OF THE LAPLACE TRANSFORM TO LTI DIFFERENTIAL SYSTEMS: STATE-SPACE ANALYSIS 6.1 State-space Representation of Continuous-time LTI Systems Definition: The state of a system at time t0 is the minimal information required that is sufficient to determine the state and the output of the system for all times, t t t0 , for the known system input at all times, t t t0 . The variables that contain this information are called state variables. LEARNING OBJECTIVES After studying this chapter, it is expected that you will: x Understand the relationship between the input and the output of LTI systems through state-space model representation. x Be able to apply and explore the procedure for solving state model representation using the Laplace transform technique. x Be able to apply the Laplace transform technique to obtain the state transition matrix of the state model. Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: State-space Analysis 455 x Be able to determine the state model and its response of an electrical system. 6.2 State Model Representations Consider a single-input single-output continuous-time LTI system described by the following second-order differential equation d2y t dt 2 a1 dy t dt a2 y t bu t . y t is the system output and u t is the system input y t a1 y t a2 y t bu t (6.1) Define the following useful set of state variables y t x1 t y t x1 t x2 t y t x2 t y t a1 y t a2 y t bu t x2 t a1 x2 t a2 y t bu t Putting (6.2) and (6.3) in matrix form, we get (6.2) (6.3) Chapter 6 456 ª º « x1 t » « » «¬ x2 t »¼ y t ª 0 « ¬ a2 1 º ª x1 º ª0 º u t a1 »¼ «¬ x1 »¼ «¬b »¼ (6.3a) ªx t º >1 0@ « x1 t » ¬ 2 ¼ (6.3b) Eqs. (6.3a) and (6.3b) can be written more compactly as X t A X t Bu t y t CX t (6.4) In general, the state equations of a system can be described by X t A X t Bu t y t C X t Du t The vector X (6.5) t is called the state vector or response of the system. If u t 0, then equation (6.5) is called a homogeneous system. If u t z 0, then equation (6.5) is called a non-homogeneous system. Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: State-space Analysis 457 6.2.1 Procedure to Find the Response of a Second-order Nonhomogeneous System Consider a second-order non-homogeneous system X t A X t Bu t Multiplying both sides by e ª º e At « X t A X t » ¬ ¼ d ª e At X t º¼ dt ¬ At , we get e At B u t e At B u t . Integrating both sides between 0 and t, we get t ª¬ e At X t X 0 º¼ ³e AO B u O dO 0 t ª¬ e At X t º¼ X 0 ³ e AO B u O d O 0 . Thus, t X t e At X 0 ³ e A t O B u O d O hom ogenous solution 0 Non hom ogenous solution (6.6) Eq. (6.6), represents the response of a second order system. Chapter 6 458 6.3 Matrix Exponential (State-transition matrix) The matrix exponential is denoted by e At I t and is computed using the Laplace transform as follows ª Aº s «1 » ¬ s¼ 1 > sI A@ 1 > sI A@ 1 1 · 1§ A A2 A3 2 3 ............ ¸ 1 ¨ s© s s s ¹ § I A A2 A3 · ¨ 2 3 4 ............ ¸ s s ©s s ¹ Taking the inverse Laplace transform we get 1 L1 > sI A@ 1 L1 > sI A@ § At A2t 2 A3t 3 · ............ ¸ ¨1 1! 2! 3! © ¹ e At Thus, The matrix exponential is e At I t ^ L1 sI A 1 `. In applying the matrix Laplace transform method, it is straightforward (although possibly tedious) to compute sI A 1 , but the computation of the inverse transform may require the use of some of the special techniques (such as partial fractions) discussed in Chapter 2. Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: State-space Analysis 459 6.3.1 Converting from State-space to Transfer Function Given the state and output equations X t A X t Bu t y t C X t Du t , taking the Laplace transform, and assuming zero initial conditions, we can deduce the transfer function as Y s X s H S C ^ > sI A@ ` B D 1 Example 6.1. Obtain the state-space representation of a system described by the following differential equation d3y t dt 3 2 d2y t dt 2 3 dy t dt 4y t u t . Solution: The order of the differential equation is three. Hence, the three-state variables are x1 t y t , x1 t dy t , x3 t dt d2y t dt 2 The first derivatives of the state variables are Chapter 6 460 x1 t x2 t (6.7) x2 t x3 t (6.8) x3 t 4 x1 t 3x2 t 2 x3 t u t (6.9) The state-space representation in matrix form (putting (6.6), (6.7), and (6.9) in matrix form) is ª º « x1 t » « » « x2 t » « » « x3 t » ¬ ¼ ª 0 1 0 º ª x1 t º ª0 º « 0 0 1 » « x t » «0 » u t . « »« 2 » « » «¬ 4 3 2 »¼ «¬ x3 t »¼ «¬1 »¼ The system output y t becomes y t ª x1 t º >1 0 0@ «« x2 t »» « x2 t » ¬ ¼ Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: State-space Analysis 461 Example 6.2. Obtain the state-space representation for the electrical circuit shown in Figure 6.1, considering Vc1 , i1 and Vc 2 as state variables and Vc1 as the output y t . Figure 6.1 Solution: The state variables for the circuit are x1 t Vc1 , x2 t i1 , x3 t Vc 2 From the relationship between the voltage Vc1 and current i1 , we obtain dx1 t dt x2 t Kirchhoff’s voltage equation around the closed-loop gives Chapter 6 462 Vs x1 t dx2 t x3 t dt 0 This equation can be rewritten as dx2 t dt x1 t x3 t Vs with current, i3 t x3 t , and current, i3 t dx3 t dt By Kirchhoff’s current law i1 i2 i3 implying that x2 t dx3 t x3 t dt . Hence, dx3 t dt x2 t x3 t The voltage VC1 is taken as the output y t , y t x1 t The state-space representation of the circuit is given by . Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: State-space Analysis ª º « x1 t » « » « x2 t » « » « x3 t » ¬ ¼ 463 ª 0 1 0 º ª x1 t º ª0 º « 1 1 1» « x t » «1 » V « »« 2 » « » s «¬ 0 1 1»¼ «¬ x3 t »¼ «¬0 »¼ and the system output y t becomes y t ª x1 t º >1 0 0@ «« x2 t »» «¬ x2 t »¼ Example 6.3. Compute e At for ª4 1º A « ». ¬0 4¼ Solution: To find the state transition matrix, we first calculate the matrix > sI A@ ª1 0 º ª 4 1 º s« »« » ¬0 1 ¼ ¬0 4 ¼ The determinant of sI A ª s 0º ª4 1 º «0 s » «0 4 » ¬ ¼ ¬ ¼ sI A is given by s 4 1 0 s4 s4 2 . We next calculate the adjoint of this matrix sI A . ª s 4 1 º « 0 s 4 »¼ ¬ Chapter 6 464 Adj sI A 1 º ªs 4 . « 0 s 4 »¼ ¬ The inverse matrix is the adjoint matrix divided by the determinant 1 > sI A@ ª 1 «s 4 « « « 0 ¬ adj sI A det sI A 1 º » s4 » 1 » » s4 ¼. 2 Taking the inverse of the elements of this matrix, we find that e At I t 1 L1 > sI A@ ªe 4t « ¬0 te 4t º » e 4t ¼ . Thus, e At ªe 4t « ¬0 te 4t º ». e 4t ¼ Example 6.4. Find the state transition matrix of the non-homogeneous system ª º « x1 t » « » «¬ x2 t »¼ ª 1 1 º ª x1 º ª0 º « 1 1» « x » «1 » u t with X 0 ¬ ¼¬ 2 ¼ ¬ ¼ and also find the response of the system. ª0 º «1 » ¬ ¼ Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: State-space Analysis 465 Solution: To find the state transition matrix, we first calculate the matrix ª1 0 º ª 1 ª s 0 º ª 1 1 º «0 s » « 1 1» ¬ ¼ ¬ ¼ 1º > sI A@ s «0 1 » « 1 1» ¬ ¼ ¬ The determinant of ¼ ª s 1 1 º « 1 s 1» ¬ ¼ sI A is given by s 1 1 1 s 1 sI A sI A , 2 s 1 1 . We next calculate the adjoint of this matrix Adj sI A ªs 1 1 º « 1 s 1» . ¬ ¼ The inverse matrix is the adjoint matrix divided by the determinant 1 > sI A@ ªs 1 1 º « » s 1 1 ¬ 1 s 1¼ adj sI A det sI A 1 2 . The state transition matrix is the inverse Laplace transform of this matrix. Finally, taking the inverse Laplace transform of each term, we obtain a state transition matrix I t e At 1 L1 > sI A@ ª cos t sin t º et « ». ¬ sin t cos t ¼ The solution of the homogeneous part is Chapter 6 466 Xh t e At X 0 0 (since the circuit is initially relaxed) The solution of the non-homogeneous part is t X nh t ³e A t O B Vs O d O with Vs O u t 1 0 X nh t t O ­ cos t O °ªe ³0 ® «« e t O sin t O ° ¯¬ X nh t ­ ª t O sin t O °« e ³0 ®« e t O cos t O °« ¯¬ X nh t ª t t O º sin t O d O » « ³ e « 0 » « t » « ³ e t O cos t O d O » «¬ 0 »¼ VC t x2 t t t e t O sin t O º ª0 º ½ ° » « » ¾ dO t O cos t O »¼ ¬1 ¼ ° e ¿ º½ » ° dO »¾ »¼ °¿ t ³e t O cos t O d O 0 t VC t ³e t O ª¬cos t cos O sin t sin O º¼ d O 0 t VC t t O e cos t ³ e cos O d O e sin t ³ eO sin O d O t 0 t 0 . Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: State-space Analysis 467 Integration by parts gives t VC t t e t cos t ³ eO cos O d O e t sin t ³ eO sin O d O 0 0 Thus, the complete solution is VC t 1 1 e t sin t e t cos t . 2 Hence, VC t x2 t 1 1 e t sin t e t cos t . 2 Example 6.5. Obtain the state-space representation for the electrical circuit shown in Figure 6.2 with , L 1H and V zero at t Figure 6.2 R1 4:, R2 6: , C 0.25 F 12Volts . Assume all currents and charges to be 0, the instant when the switch is closed. Chapter 6 468 Solution: Appling KVL to the above loops, we get Loop-1: L di1 R1 i1 i2 dt di1 4 i1 i2 dt V 12 i1' 4i1 4i2 12 (6.10) Loop-2: 1 i2 dt R2i2 R1 i2 i1 C³ 0 1 i2 dt 6i2 4 i2 i1 0.25 ³ 0 4 ³ i2 dt 10i2 4i1 0 4i2 10i2' 4i11 0 i2' differentiating , we get 0.4i1' 0.4i2 i2' 0.4 4i1 4i2 12 0.4i2 i2' 1.6i1 1.2i2 4.8 (6.11) Putting (6.10) and (6.11) in matrix form, we get Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: State-space Analysis ªi1' t º «' » ¬«i2 t ¼» I t 469 4 º ªi1 º ª12 º ª 4 « 1.6 1.2 » «i » « 4.8 » u t ¬ ¼¬ 2 ¼ ¬ ¼ AI t Bu t Example 6.6. Find the state transition matrix of the homogeneous system ª º « x1 t » « » ¬« x2 t ¼» ª 0 1 º ª x1 º « 2 3» « x » with X 0 ¬ ¼¬ 2 ¼ ª0 º «1 » ¬ ¼ and find the response of the system. Solution: To find the state transition matrix, we first calculate the matrix ª1 0 º ª 0 1º > sI A@ s «0 1 » « 2 3» ¬ ¼ ¬ ¼ ª s 0º ª 0 1 º «0 s » « 2 3» ¬ ¼ ¬ ¼ . The determinant of sI A sI A is given by s 1 2 s3 s 1 s 2 . We next calculate the adjoint of this matrix Adj sI A ª s 3 1º « 2 s » . ¬ ¼ sI A , ª s 1 º « » ¬ 2 s 3¼ Chapter 6 470 The inverse matrix is the adjoint matrix divided by the determinant 1 > sI A@ 1 > sI A@ det sI A ª s 3 1º s 1 s 2 ¬« 2 s ¼» ª s3 « « s 1 s 2 « 2 « ¬« s 1 s 2 º » s 1 s 2 » » s » s 1 s 2 ¼» . adj sI A 1 1 Expressing each element of this matrix in terms of partial fractions, we get 1 > sI A@ 1 ª 2 « s 1 s 2 « « 2 2 « s2 ¬ s 1 1 1 º s 1 s2 » » 1 2 » » s 1 s2 ¼ The state transition matrix is the inverse Laplace transform of this matrix. Finally, taking the inverse Laplace transform of each term, we obtain a state transition matrix I t e At 1 L1 > sI A@ ª 2e t e 2t « t 2 t ¬ 2e 2e e t e 2t º » e t 2e 2t ¼ The response of the system is X t e At X 0 ª 2e t e 2t « t 2 t ¬ 2e 2e e t e 2t º ª1 º »« » e t 2e 2t ¼ ¬0 ¼ . Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: State-space Analysis 471 ª 2e t e 2t º « t 2 t » ¬ 2e 2e ¼ . X t Example 6.7. Obtain the state-space representation of the circuit shown in Figure 6.3 considering the current through the inductor and voltage across the capacitor as state variables and the voltage across the capacitor as the output y t . Figure 6.3 Solution: The state variables for the circuit are x1 t I L t , x2 t Vc1 t since the voltage across the capacitor is equal to the voltage across the series inductor and resistor branch, we obtain x2 t dx1 t x1 t dt . This equation can be rewritten as Chapter 6 472 dx1 t dt x1 t x2 t . Kirchhoff’s voltage equation around the closed-loop gives Vs t i1 t x2 t 0 Hence, i1 t x2 t Vs t . By Kirchhoff’s current law i1 t x1 t dx2 t dt Therefore, x2 t Vs t x1 t dx2 t dt This equation can be rewritten as dx2 t dt x1 t x2 t Vs t . The voltage Vc y t t is taken as the output y t , x2 t The state-space representation of the circuit is given by Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: State-space Analysis ª º « x1 t » « » «¬ x2 t »¼ 473 ª 1 1 º ª x1 t º ª0 º » « » Vs t . « »« ¬ 1 1¼ ¬ x2 t ¼ ¬1 ¼ and the system output y t becomes y t ªx t º >0 1@ « x1 t » . ¬ 2 ¼ Example 6.8. Find the matrix exponential of A ª1 1º « 2 2 » . ¬ ¼ Solution: To find the state transition matrix, we first calculate the matrix ª1 0 º ª1 1º ª s 0 º ª1 1º «0 s » « 2 2 » ¬ ¼ ¬ ¼ > sI A@ s «0 1 » « 2 2» ¬ ¼ ¬ ¼ sI A ªs 1 1 º « 2 s 2 » ¬ ¼ . The determinant of sI A sI A is given by s 1 1 2 s 2 s s 1 . We next calculate the adjoint of this matrix Adj sI A ª s 1 1 º « 2 s 2» . ¬ ¼ The inverse matrix is the adjoint matrix divided by the determinant Chapter 6 474 1 > sI A@ 1 ª s 2 1 º s 1¼» s s 1 ¬« 2 adj sI A det sI A 1 > sI A@ ª s2 « « s s 1 « 2 « «¬ s s 1 1 º » s s 1 » s 1 » » s s 1 »¼ Expanding each term in the matrix on the right by partial fractions yields 1 > sI A@ 1 ª2 « s s 1 « «2 2 « s 1 ¬s 1 1º » s 1 s » 1 2 » » s s 1 ¼ . Finally, taking the inverse Laplace transform of each term, we obtain a state transition matrix is I t e At 1 L1 > sI A@ ª 2 et « t ¬ 2 2e et 1 º » 2e t 1¼ Example 6.9. Find the state transition matrix of the non-homogeneous system ª º « x1 t » « » «¬ x2 t »¼ ª 0 1 º ª x1 º ª0 º « 6 5» « x » «1 » u t with X 0 ¬ ¼¬ 2 ¼ ¬ ¼ and find the response of the system. ª0 º «1 » ¬ ¼ Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: State-space Analysis 475 Solution: To find the state transition matrix, we first calculate the matrix ª1 0 º ª 0 1º > sI A@ s «0 1 » « 6 5» ¬ ¼ ¬ The determinant of ª s 1 º «6 s 5» ¬ ¼ sI A is given by s 1 2 s3 sI A ¼ ª s 0º ª 0 1 º «0 s » « 6 5» ¬ ¼ ¬ ¼ sI A , s2 s3 . We next calculate the adjoint of this matrix Adj sI A ª s 5 1º « 6 s » . ¬ ¼ The inverse matrix is the adjoint matrix divided by the determinant 1 > sI A@ 1 > sI A@ det sI A ª s 5 1º s 1 s 2 «¬ 6 s »¼ ª s5 « « s2 s3 « 6 « «¬ s 2 s 3 º » s2 s3 » » s » s 2 s 3 »¼ . adj sI A 1 1 Expanding each term in the matrix on the right by partial fractions yields Chapter 6 476 2 ª 3 « s2 s3 « « 6 6 « s3 ¬ s2 1 > sI A@ 2 3 º s2 s3 » » 2 3 » » s2 s3 ¼ . The state transition matrix is the inverse Laplace transform of this matrix. Finally, taking the inverse Laplace transform of each term, we obtain a state transition matrix I t e 1 At L 1 > sI A@ ª 3e 2t 2e 3t « « 6e 2t 6e 3t ¬ º » 2 t 3t » 2e 3e ¼ e 2t e 3t . The solution of the homogeneous part is At ª 3e 2t 2e 3t « « 6e 2t 6e 3t ¬ Xh t e X 0 Xh t ª e 2t e 3t º « » « 2e 2t 3e 3t » ¬ ¼. º ª0 º » 2 t 3t » « 1 » 2e 3e ¼ ¬ ¼ e 2t e 3t The solution of the non-homogeneous part is t X nh t ³e 0 A t O B u O dO with u O 1 Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: State-space Analysis 2 t O ­ª 2e 3 t O ° « 3e ³0 ®« 6e2 t O 6e3 t O °« ¯¬ e 2 t O e3 t O t X nh t 2e2 t O 3e3 t O X nh t 2 t O ­ª e 3 t O °« e ³0 ®« 2e2 t O 3e3 t O °« ¯¬ X nh t ª « « « « «¬ t X nh t t ³e 2 t O e 3 t O d O 0 t ³ 2e 2 t O 3e 3 t O 0 ª 1 1 2t 1 3t º «2 2 e 3e » « » e 2t e 2t ¬ ¼ 477 ½ º » ª0 º ° d O » «¬1 »¼ ¾ ° »¼ ¿ º½ » ° dO »¾ »¼ °¿ º » » » dO » »¼ . Thus, the complete solution is ª e 2t e 3t º ª 1 1 e 2t 1 e 3t º » « » «2 2 3 » « 2e 2t 3e 3t » « 2 t 3t e e ¬ ¼ ¬ ¼ X t X h t X nh t X t ª 1 1 2t 2 3t º «2 2 e 3 e » « » «¬ e 2t 2e 3t »¼ . Chapter 6 478 Example 6.10. Using the Laplace transform approach, obtain an expression for the state X t of the system characterized by the state equation ª º « x1 t » « » «¬ x2 t »¼ ª 1 0 º ª x1 º ª1 º « 1 3» « x » «1 » u t with X 0 ¬ ¼¬ 2 ¼ ¬ ¼ ª1 º «1 » ¬ ¼ Solution: To find the state transition matrix, we first calculate the matrix ª1 0 º ª 1 > sI A@ s «0 1 » « 1 ¬ ¼ ¬ The determinant of ª s 0 º ª 1 0 º «0 s » « 1 3» ¬ ¼ ¬ ¼ ªs 1 0 º « 1 s 3» ¬ ¼ sI A is given by s 1 0 1 s 3 sI A 0º 3»¼ sI A , s 1 s 3 . We next calculate the adjoint of this matrix Adj sI A ªs 3 0 º « 1 s 1» . ¬ ¼ The inverse matrix is the adjoint matrix divided by the determinant 1 > sI A@ adj sI A det sI A ªs 3 0 º s 1»¼ s 1 s 3 «¬ 1 1 Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: State-space Analysis 1 > sI A@ 1 ª « s 1 « « 1 « ¬ s 1 s 3 479 º » » 1 » » s3 ¼ . 0 Expanding each term in the matrix on the right by partial fractions yields 1 > sI A@ 1 ª « s 1 « «1 ª 1 1 º « « » s3 ¼ «¬ 2 ¬ s 1 º » » 1 » » s 3 »¼ . 0 The state transition matrix is the inverse Laplace transform of this matrix. Finally, taking the inverse Laplace transform of each term, we obtain a state transition matrix I t e At 1 L ^> sI A@ ` 1 ª et « « 1 e t e 3t ¬« 2 The solution of the homogeneous part is ª et « « 1 e t e 3t ¬« 2 Xh e At X 0 Xh ª º et « » « 1 e t e 3t » ¬« 2 ¼» . 0 º » ª1º « » e 3t » ¬1¼ »¼ 0 º » e 3t » ¼» . Chapter 6 480 The solution of non-homogeneous part is (alternating approach) X Nh ^ 1 L1 > sI A@ b U s 1 > sI A@ bU s 1 > sI A@ bU s § ¨U s © ` ­ª 1 °« s 1 °« ®« °« 1 ª 1 1 º » °« 2 « s 1 s3 ¼ ¯¬ ¬ L u t 1· ¸ s¹ º ½ » ° » ª1º ° 1 « »¾ 1 » ¬1¼ ° s » s 3 »¼ °¿ 0 1 ª º « » s s 1 « » «1 ª 1 » 1 º « « »» «¬ 2 ¬ s s 1 s s 3 ¼ »¼ . Expanding each term in the matrix on the right by partial fractions yields 1 > sI A@ bU s X nh X t 1 L 1 1 ª º « » s s 1 « » «§ 5 1 1 1 1 1 ·» «¨ ¸» «¬¨© 6 s 2 s 1 6 s 3 ¸¹ »¼ ^> sI A@ bU s ` 1 X h t X nh t ª º 1 et « » « 5 1 e t 1 e 3t » 6 ¬« 6 2 ¼» º ª º ª 1 et et » « »« « 1 e t e 3t » « 5 1 e t 1 e 3t » «¬ 2 »¼ «¬ 6 2 »¼ . 6 Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: State-space Analysis 481 Thus, the complete solution is X h t X nh t X t ª 1 º «1 » « e 3t » ¬3 ¼. Example 6.11. Find the matrix exponential of A ª0 1º « 8 6 » . ¬ ¼ Solution: To find the state transition matrix, we first calculate the matrix ª1 0 º ª 0 1º ª s 0º ª 0 1 º «0 s » « 8 6 » ¬ ¼ ¬ ¼ > sI A@ s «0 1 » « 8 6» ¬ ¼ ¬ The determinant of ª s 1 º «8 s 6 » ¬ ¼ sI A is given by s 1 8 s6 sI A ¼ sI A , s 2 6s 8 . We next calculate the adjoint of this matrix Adj sI A ª s 6 1º « 8 s » . ¬ ¼ The inverse matrix is the adjoint matrix divided by the determinant 1 > sI A@ adj sI A det sI A ª s 6 1º s 2 s 4 «¬ 8 s »¼ 1 Chapter 6 482 1 > sI A@ s6 ª « s2 s4 « « 8 « ¬ s2 s4 1 º s2 s4 » » » s » s2 s4 ¼ . Expanding each term in the matrix on the right by partial fractions yields 1 > sI A@ ª 2 1 « s4 « s2 « 4 4 « s4 «¬ s 2 1§ 1 1 ·º ¨¨ ¸» 2© s2 s 4 ¹¸ » » 2 1 » s2 s 4 »¼ . The state transition matrix is the inverse Laplace transform of this matrix. Finally, taking the inverse Laplace transform of each term, we obtain the state transition matrix I t e At 1 L ^> sI A@ ` 1 ª 2 t 4 t « 2e e « 2 t 4 t ¬ 4e 4e 1 2t º e e 4t » 2 » e 2t 2e 4t ¼ . Example 6.12. Find the state transition matrix of the homogeneous system ª º « x1 t » « » «¬ x2 t »¼ ª 0 2 º ª x1 º « 2 5» « x » with X 0 ¬ ¼¬ 2 ¼ and find the response of the system. ª0 º «1 » ¬ ¼ Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: State-space Analysis 483 Solution: To find the state transition matrix, we first calculate the matrix ª1 0 º ª 0 2º > sI A@ s «0 1 » « 2 5» ¬ ¼ ¬ ¼ ª s 0º ª 0 2 º « »« » ¬0 s ¼ ¬ 2 5¼ sI A , ª s 2 º « » ¬ 2 s 5¼ . The determinant of sI A is given by s 2 2 s5 sI A s 1 s 4 . Next, we calculate the adjoint of this matrix Adj sI A ª s 5 2º « 2 s » . ¬ ¼ The inverse matrix is the adjoint matrix divided by the determinant 1 > sI A@ 1 > sI A@ adj sI A det sI A s5 ª « s 1 s 4 « « 2 « ¬ s 1 s 4 ª s 5 2º s 1 s 4 «¬ 2 s »¼ 1 2 º s 1 s 4 » » » s » s 1 s 4 ¼ Expanding each term in the matrix on the right by partial fractions yields Chapter 6 484 1 > sI A@ ª§ 4 1 1 1 · «¨¨ ¸¸ «© 3 s 1 3 s 4 ¹ « « 2 § 1 1 · ¸ « 3 ¨¨ s 1 s 4 ¸¹ ¬ © 2§ 1 1 · º ¨¨ ¸ » 3 © s 1 s 4 ¹¸ » » § 1 1 4 1 ·» ¨¨ ¸¸ » © 3 s 1 3 s 4 ¹¼ . The state transition matrix is the inverse Laplace transform of this matrix Finally, taking the inverse Laplace transform of each term, we obtain the state transition matrix I t e At ^ 1 L1 > sI A@ ` ª§ 4 t 1 4t · 2 t º e e 4t » «¨ 3 e 3 e ¸ 3 ¹ «© » «2 § 1 t 4 4t · » t 4 t « e e ¨ e e ¸» 3 © 3 ¹¼ ¬3 . The solution of the homogeneous part is ª§ 4 t 1 4t · 2 t º e e 4t » «¨ 3 e 3 e ¸ 0 3 ¹ «© » ª« º» «2 § 1 t 4 4t · » ¬1 ¼ t 4 t « e e ¨ e e ¸» 3 © 3 ¹¼ ¬3 Xh e At X 0 Xh ª 2 t º 4 t « 3 e e » « ». «§ 1 e t 4 e 4t · » ¸» «¬¨© 3 3 ¹¼ Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: State-space Analysis 485 Example 6.13. Convert the state and output equations to a transfer function ª º « x1 t » « » « x2 t » « » « x3 t » ¬ ¼ ª 0 1 0 º ª x1 t º ª1 º « 0 0 1 » « x t » «0 » u t « »« 2 » « » «¬ 1 2 3»¼ «¬ x3 t »¼ «¬0 »¼ with the system output y t , y t ª x1 t º >1 0 0@ «« x2 t »» « x2 t » ¬ ¼. Solution: The general state and output equations are X t A X t Bu t y t C X t Du t and the transfer function is given by H S Y s X s We first find C ^ > sI A@ ` B D sI A as 1 (6.14) Chapter 6 486 ª1 0 0º ª 0 1 0 º ª s 0 0º ª 0 1 0 º ª s 1 0 º s ««0 1 0»» «« 0 0 1 »» ««0 s 0 »» «« 0 0 1 »» ««0 s 1 »» ¬«0 0 1 ¼» ¬« 1 2 3¼» ¬«0 0 s ¼» ¬« 1 2 3¼» ¬«1 2 s 3¼» > sI A@ The determinant of sI A is given by s 1 0 0 s 1 1 2 s3 sI A s 3 3s 2 2s 1 . The inverse matrix is the adjoint matrix divided by the determinant ª s 2 3s 2 s 3 1º 1 « » 2 s 3s s » 1 « 3 2 s 3s 2 s 1 « s 2 s 1 s 2 »¼ ¬ adj sI A 1 > sI A@ det sI A Substituting sI A 1 , B, C and D into Eq. (6.14), where B ª1 º «0 » « » «¬0 »¼ C >1 0 0@ D 0 we obtain the final result for the transfer function H S Y s X s C ^ > sI A@ ` B D 1 Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: State-space Analysis s 2 3s 2 H S s 3 3s 2 2 s 1 487 . Example 6.14. Convert the state and output equations to a transfer function ª º « x1 t » « » ¬« x2 t ¼» ª 1 1 º ª x1 º ª1 º « 1 1» « x » «0 » u t ¬ ¼¬ 2 ¼ ¬ ¼ with the system output y t , y t ªx t º >1 0@ « x1 t » . ¬ 2 ¼ Solution: We have the general state and output equations are X t A X t Bu t y t C X t Du t and the transfer function is given by H S Y s X s C ^ > sI A@ ` B D 1 To find the state transition matrix, we first calculate the matrix (6.15) sI A , Chapter 6 488 ª1 0 º ª 1 1º > sI A@ s «0 1 » « 1 1» ¬ ¼ ¬ ¼ ª s 0 º ª 1 1 º «0 s » « 1 1» ¬ ¼ ¬ ¼ ª s 1 1 º « 1 s 1» ¬ ¼ . The determinant of sI A is given by s 1 1 1 s 1 sI A s 2 2s 2 . Next, we calculate the adjoint of this matrix ªs 1 1 º « 1 s 1» . ¬ ¼ Adj sI A The inverse matrix is the adjoint matrix divided by the determinant 1 > sI A@ adj sI A det sI A Substituting B sI A ª1 º «0 » ¬ ¼, and D 1 C ªs 1 1 º 1 « » s 2 2s 2 ¬ 1 s 1¼ , B, C and D into Eq. (6.15), where >1 0@ 0 we obtain the final result for the transfer function H S Y s X s C . ^ > sI A@ ` B D 1 Application of the Laplace Transform to LTI Differential Systems: State-space Analysis H S 489 s 1 . s 2s 2 2 Summary In chapters 3 and 4, we specified a continuous-time LTI system model using a transfer function or differential equation. For both cases, the system input-output characteristics have been given. In this chapter, another model — the state-variable model — has been developed. We have described and explained the concept of state-space representation of continuous-time LTI systems and also explained the state vector and state transition matrix using the Laplace transform method. x We started with a definition of state variables. State model representations of LTI systems were developed and analyzed by finding the system response. The solution of state model equations, for both homogeneous and non-homogeneous LTI systems, has been illustrated using several solved examples. x The state transition matrix (matrix exponential) has been defined using the Laplace transform method. The exponential matrix evaluation using the Laplace transform method has been illustrated using several solved examples. CHAPTER 7 LAPLACE TRANSFORM METHODS FOR PARTIAL DIFFERENTIAL EQUATIONS (PDES) 7.1 Introduction In sections 4.2 and 4.3, we illustrated the effective use of Laplace transforms in solving ordinary differential equations. The transform replaces a differential equation in y t transform Y with an algebraic equation in its s . It is then a matter of finding the inverse transform of Y s , either by the partial fraction method or by using Table 2.1. The Laplace transform can also be used to solve certain types of partial differential equations involving two or more independent variables. When the transform is applied to the variable t in a partial differential equation for a function u x, t , the result is an ordinary differential equation for the transform U x, s . The ordinary differential equation is solved for U x, s and the function is inverted to yield u x, t . LEARNING OBJECTIVES On reaching the end of this chapter, we expect that you will have understood and be able to apply the following: Laplace Transform Methods for Partial Differential Equations (PDEs) 491 x Determine the Laplace transform of partial derivatives. x The use of the Laplace transform in solving partial differential equations with initial and boundary conditions. x The use of the Laplace transform in solving special partial differential equations like heat and wave equations. 7.2 The Laplace transforms of u x, t and its partial derivatives First, we obtain the Laplace transforms of the partial derivatives wu wu w 2u w 2u , , , wt wx wt 2 wx 2 u x, t , t ! 0 Using the same procedure as that used to of the function obtain the Laplace transform of standard derivatives in property 1. 5.2 (Chapter 1), we have the following L ^u x, t ` f ³e st u x, t d t U x, s 0 a ­ wu x, t ½ L® ¾ ¯ wt ¿ (7.1) L ^ut x, t ` f ³e st ut x, t d t 0 Using integration by parts, we get L ^ut x, t ` e st u x, t f 0 f s ³ e st u x, t d t 0 Chapter 7 492 so that L ^ut x, t ` sU x, s u x, 0 (7.2) b Writing v x, t wu , and repeated application of (7.2), gives wt ­ wv ½ L ® ¾ sV x, s v x,0 ¯ wt ¿ ­ wv ½ L ® ¾ s ¬ª sU x, s u x,0 ¼º v x,0 ¯ wt ¿ ­° w 2u x, t ½° 2 L® ¾ L ^utt x, t ` s U x, s su x, 0 ut x, 0 . 2 ¯° wt ¿° c we have f ­ wu x, t ½ L® ¾ ¯ wx ¿ L ^u x x, t ` ­ wu x, t ½ L® ¾ ¯ wx ¿ f º d ª st « ³ e u x, t d t » dx ¬ 0 ¼ ³e 0 st w ^u x, t ` d t wx d ^U x, s ` U x x, s dx so that ­ wu x, t ½ L® ¾ ¯ wx ¿ d ^U x, s ` dx (7.3) Laplace Transform Methods for Partial Differential Equations (PDEs) d Writing v x, t wu , and repeated application of (7.3), gives wx ­ wv ½ d L® ¾ L ^v x, t ` ¯ wx ¿ dx ` dxd ©¨§ dxd U x, s ¹¸· ^ so that 2 °­ w u x, t °½ L® ¾ 2 °¯ wx °¿ d2 ^U x, s ` U xx x, s dx 2 Table 7.1 Laplace Transform Partial Derivative Pairs S.N Transform Partial Derivative Pairs 1 ­ wu ½ L ® ¾ sU x, s u x,0 ¯ wt ¿ 2 ­ w 2u ½ L ® 2 ¾ s 2U x, s su x, 0 ut x, 0 ¯ wt ¿ 3 ­ wu ½ d L® ¾ ^U x, s ` ¯ wx ¿ dx 4 ­ w 2u ½ L® 2 ¾ ¯ wx ¿ d2 ^U x, s ` dx 2 5 ­ w nu ½ L® n ¾ ¯ wx ¿ dn ^U x, s ` , n 1, 2,3,..... dx n 493 Chapter 7 494 7.2.1 Steps in the Solution of a PDE by Laplace Transform The procedure for solving partial differential equations by Laplace transform may be summarized as follows: Step 1: Apply the Laplace transform (using Table 7.1) to convert the given PDE into an ordinary differential equation (ODE) using the terms U x, s . Step 2: Find the general solution of the ODE and use the boundary and/or initial conditions of the original problem to determine the precise form of the transform U x, s . Step 3: Invert the transform U x, s to find the required solution u x, t . Example 7.1 Solve the initial-boundary value problem wu x, t wx 2 wu x, t wt u x, t , u x,0 6e3 x bounded for all x ! 0, t ! 0. Solution: Taking the Laplace transforms of the given partial differential equation with respect to t , we obtain dU x, s dx 2 ^sU x, s u x, 0 ` U x, s in which we have also used the given initial condition. Laplace Transform Methods for Partial Differential Equations (PDEs) 495 Because only derivatives with respect to x remain, we replace the partial derivative with an ordinary derivative, dU x, s 2 s 1 U x, s dx 12e 3 x . This is a linear first-order ODE with constant coefficients. We solve it by finding the complementary function integral PF , where C.F is the general solution of the homogeneous differential equation C .F U h x , s c1 e 2 s 1 x and the particular integral is P.I1 12 P.I1 6 CF and particular 1 e 3 x replace D a D 2s 1 D 3 1 e 3 x 2s Now we have the general solution U x, s U h x, s U Nh x, s U x, s c1 e 2 s 1 x 6 1 e 3 x . 2s Chapter 7 496 where c1 is an arbitrary constant. Since u x, t must be bounded as x o f, we must have U x, s also bounded as x o f. . As such, we must choose c1 0. Hence, U x, s 6 1 e 3 x 2s . Taking the inverse Laplace transform, we get 6 e 2t 3 x . 6e2t e 3 x u x, t Example 7.2. Solve the initial-boundary value problem wu x, t wx wu x, t wt x, x ! 0, t ! 0 with the boundary and initial conditions u x,0 0, x ! 0, and u 0, t 0, t ! 0. Solution: Apply the Laplace transform with respect to time to the PDE equation to obtain dU x, s dx dU x, s dx sU x, s u x, 0 sU x, s x s x s Laplace Transform Methods for Partial Differential Equations (PDEs) This is an ordinary differential equation if U 497 x, s is regarded as a function of x alone, s being a parameter. The transformed differential equation is a linear first-order ODE. Comparing with the standard form dU PU dx here P Q x s s and Q and we solve it by finding the integrating factor I .F e³ sdx e sx . The formula for the solution, U I .F ³ Q I .F . dx C U x, s e sx U x, s sx x ³ e s dx C e sx s sx ³ e x dx C e sx We can use integration by parts to evaluate the integral U x, s x 1 3 C e sx 2 s s We can evaluate the constant C using the boundary conditions Chapter 7 498 0 U 0, s 1 C C s3 1 s3 so we have x 1 1 e sx 3 3 2 s s s U x, s Taking the inverse Laplace transform, we have xt u x, t tx 2 2 t2 u tx . 2 Example 7.3. Solve the initial-boundary value problem w 2 u x, t w 2 u x, t wt 2 wx 2 , 0 x 1, t ! 0 with boundary and initial conditions here u 0, t u x,0 0, wu x,0 wt 0 u 1, t 2sin S x 4sin 3S x , 0 x 1. Solution: Taking the Laplace transform and applying the initial condition, the transformed equation becomes d 2U x, s dx 2 s 2U x, s 2sin S x 4sin 3S x Laplace Transform Methods for Partial Differential Equations (PDEs) This is an ordinary differential equation, if U function of here x alone, s 499 x, s is regarded as a being a parameter. The transformed differential equation is a linear second-order ODE D 2 s 2 U x, s 2sin S x 4sin 3S x This is a differential form of linear second-order ODE with constant coefficients. We solve it by finding the complementary function and particular integral where C.F is the general solution of the homogeneous problem C .F U h x, s c1 e s x c2 e s x and the particular integral is P.I1 2 P.I1 2 P.I 2 4 P.I1 4 1 sin S x 2 D s2 replace D 2 S 2 1 sin S x S s2 2 1 sin 3S x 2 D s2 1 sin 3S x 9S s 2 2 Now, we have the general solution U x, s D2 a 2 U h x, s U Nh x, s replace D 2 D2 a 2 9S 2 Chapter 7 500 c1 e s x c2 e s x U x, s 2 4 sin S x sin 3S x 2 2 9S s 2 S s 2 We can evaluate the constants c1 and c2 using the boundary condition u 0, t 0 U 0, s 0 and u 1, t 0 U 1, s 0 so we have U 0, s 0 c1 c2 and U 1, s Solving for c1 and c2, we get c1 0 0 c1 e s c2 e s . c2 therefore, 2 4 sin S x sin 3S x 2 2 9S s 2 S s U x, s 2 . Taking the inverse Laplace transform, we get u x, t 2 S sin S t sin S x 4 sin 3S t sin 3S x . 3S Example 7.4. A very long taut string is supported from below so that it lies motionless on the positive x axis. At time t 0, the support is removed and gravity is permitted to act on the string. If the end x 0 is fixed at origin, the initial boundary-value problem describing displacements u w 2 u x, t wt 2 c2 w 2 u x, t wx 2 g, x, t of points in the string is x ! 0, t ! 0 with boundary and initial conditions Laplace Transform Methods for Partial Differential Equations (PDEs) 501 u 0, t 0, t ! 0, u x,0 0, x ! 0, ut x,0 0, x ! 0, where g 9.81, and c ! 0 is a constant depending on the material and tension of the string. Use Laplace transforms to solve this problem. Solution: Take the Laplace transform and apply the initial condition c 2 d 2U x, s dx 2 d 2U x, s dx 2 s 2U x, s s u x, 0 ut x, 0 s2 2 U x, s c g s g 2 cs This is an ordinary differential equation if U x, s is regarded as a function of x alone, s being a parameter. The transformed differential equation is a linear second-order ODE § 2 s2 · ¨ D 2 ¸ U x, s c ¹ © g c2 s This is a differential form of a linear second-order ODE with constant coefficients. Chapter 7 502 We solve it by finding the complementary function and particular integral, where C.F is the general solution of the homogeneous problem C .F U h x , s c1 e sx c c2 e sx c and the particular integral is P.I U Nh x, s P.I U Nh x, s g 1 e0 x 2 2 c s § 2 §s· · ¨¨ D ¨ ¸ ¸¸ replace D 0 ©c¹ ¹ © g 3 s Now we have the general solution U x, s U h x, s U Nh x, s U x, s c1 e sx c c2 e sx c g s3 (7.4) We can evaluate the constants c1 and c2 using the boundary condition u 0, t 0 U 0, s 0 and u 1, t 0 U 1, s 0 For this function to remain bounded as x o f, we must set c1 which case condition (7.4) implies that c2 Thus, g s3 0, in Laplace Transform Methods for Partial Differential Equations (PDEs) 503 g sx c 1 e s3 . U x, s Taking the inverse Laplace transform, we have 2 g § 2 § x · § x ·· ¨ t ¨ t ¸ u ¨ t ¸ ¸¸ . 2 ¨© © c ¹ © c ¹¹ u x, t Example 7.5. Solve the initial-boundary value problem wu x, t wx wu x, t wt 2u x, t 0, x ! 0, t ! 0 with boundary and initial conditions u x,0 sin x, x ! 0, and u 0, t 0, t ! 0. Solution: Applying the Laplace transform with respect to time to the PDE equation, we obtain dU x, s dx dU x, s dx sU x, s u x, 0 2U x, s s 2 U x, s 0 sin x This is an ordinary differential equation if U x, s is regarded as a function of x alone, s being a parameter. The transformed differential equation is a linear first-order ODE. Compared to the standard form Chapter 7 504 dU PU dx Q s 2 and Q sin x . here, P We solve it by finding the integrating factor I .F e³ s 2 dx e s2 x . The formula for a solution is ³ Q I .F . dx C U I .F U x, s e s 2 x U x, s ³e s2 x sin x dx C e s 2 x ³ e s 2 x sin x dx C e s 2 x by integration, we get U x, s 1 ª s 2 sin x cos x º¼ C e s 2 x s 4s 5 ¬ 2 We can evaluate the constant C using the boundary condition 1 C C s 4s 5 0 U 0, s 2 1 s 4s 5 2 so we have U x, s 1 1 ª¬ s 2 sin x cos x º¼ 2 e s 2 x s 4s 5 s 4s 5 2 Laplace Transform Methods for Partial Differential Equations (PDEs) U x, s 505 ­ ­ ½ ½ 1 1 ° s2 ½ ° ° ° 2 x ­ ° sx ° sin x ® ¾ cos x ® ¾ e ®e ¾ 2 2 2 s 2 1° ° ° ° ¯ s 2 1° ¿ ¯ s 2 1° ¿ ¯ ¿ Taking the inverse Laplace transform, we have ^ ` sin x e 2t cos t cos x e 2t sin t e 2 x e 2 t x sin t x u t x . u x, t e 2t ª¬sin x t sin t x u t x º¼ . u x, t Example 7.6. Solve the initial-boundary value problem w 2 u x, t w 2 u x, t wt 2 wx 2 , 0 x 1, t ! 0 with boundary and initial conditions u 0, t 0, u 1, t u x,0 0, 0 wu x,0 wt sin 2S x , 0 x 1. Solution: Taking the Laplace transform and applying the initial condition, we have d 2U x, s dx 2 s 2U x, s sin 2S x . This is an ordinary differential equation if U x, s is regarded as a function of x alone, s being a parameter. The transformed differential equation is a linear second-order ODE Chapter 7 506 D 2 s 2 U x, s sin 2S x This is a differential form of a linear second-order ODE with constant coefficients. We solve it by finding the complementary function and particular integral where C.F is the general solution of the homogeneous problem C.F U h x, s c1 e s x c2 e s x and the particular integral is P.I P.I U Nh x, s U Nh x, s 1 sin 2S x D s2 replace D 2 2 D2 a 2 4S 2 1 sin 2S x 4S s 2 2 Now we have the general solution U x, s U h x, s U Nh x, s U x, s c1 e s x c2 e s x 1 sin 2S x 4S s 2 2 We can evaluate the constants c1 and c2 using the boundary condition u 0, t 0 U 0, s so we have 0 and u 1, t 0 U 1, s 0 Laplace Transform Methods for Partial Differential Equations (PDEs) U 0, s 0 c1 e s c2 e s 0 c1 c2 and U 2, s Solving for c1 and c2 we get c1 507 . 0 c2 therefore, U x, s 1 sin 2S x 4S s 2 2 . Taking the inverse Laplace transform, we have u x, t 2 3e 4S t sin 2S x . Example 7.7. A very long taut string is supported from below so that it lies motionless on a positive x axis. At time t 0, the support is removed and gravity is permitted to act on the string. If the end x 0 is fixed at origin, the initial boundary-value problem describing displacements u w 2 u x, t w 2 u x, t wt 2 wx 2 , x, t of points in the string is x ! 0, t ! 0 with boundary and initial conditions u 0, t 1, t ! 0, u x,0 0, x ! 0, lim u x, t 0, t ! 0. x of Chapter 7 508 Here, u x, t represents the temperature of a very long rod that, initially, is at a temperature of 0 ºC and for which, at time t 0, the one end that is nearest to us is raised to, and held thereafter at 1 ºC. Note that we require u x, t o f as x o f. Solution: Taking the Laplace transform and applying the initial condition d 2U x, s dx 2 d 2U x, s dx 2 sU x, s u x,0 sU x, s 0 . This is an ordinary differential equation if U x, s is regarded as a function of x alone, s being a parameter. The transformed differential equation is a linear second-order homogeneous ODE D 2 s U x, s 0 with the general solution C.F U x, s c1 e s x c2 e s x . Now we have the general solution U x, s c1 e s x c2 e s x . We can evaluate the constants c1 and c2 using the boundary condition Laplace Transform Methods for Partial Differential Equations (PDEs) u 0, t 509 1 s 1 U 0, s so we have U 0, s u0 s c1 c2 . For this function to remain bounded as ݔ՜ ҄, we must therefore set c1 0, c2 U x, s 1 s 1 sx e s Taking the inverse Laplace transform, we have u x, t § x · erfc ¨ ¸. © 2 kt ¹ where erfc (x) is the complementary error function erfc x 1 erf x 1 2 x W 2 e dW S ³ 0 2 f W 2 e dW . S ³ x Example 7.8. Solve the initial-boundary value problem w 2 u x, t wt 2 c 2 w 2 u x, t , 0 x L, t ! 0 wx 2 with boundary and initial conditions u 0, t 0, u L, t 0 Chapter 7 510 § S · wu x, 0 A sin ¨ x ¸ , wt ©L ¹ u x, 0 0, 0 x 1. Solution: Taking the Laplace transform and applying the initial condition d 2U x, s dx 2 2 §s· ¨ ¸ U x, s ©c¹ s §S · 2 A sin ¨ x ¸ c ©L ¹ This is an ordinary differential equation if U x, s is regarded as a function of x alone, s being a parameter. The transformed differential equation is a linear second-order ODE § 2 § s ·2 · ¨¨ D ¨ ¸ ¸¸ U x, s ©c¹ ¹ © s §S · 2 A sin ¨ x ¸ c ©L ¹ This is a differential form linear second order ODE with constant coefficients. We solve it by finding the complementary function and particular integral where C.F is the general solution of the homogeneous problem C .F U h x, s c1 e s c x c2 e s c x and the particular integral is Laplace Transform Methods for Partial Differential Equations (PDEs) P.I U Nh x, s replace D 2 D2 P.I 511 s 1 §S · 2A sin ¨ x¸ c § 2 § s ·2 · © L ¹ ¨¨ D ¨ ¸ ¸¸ ©c¹ ¹ © a 2 S2 L2 U Nh x, s As §S · sin ¨ x ¸ 2 2 2 s c S L ©L ¹ 2 . Now we have the general solution U x, s U h x, s U Nh x, s U x, s c1 e s c x c2 e s c x As §S · sin ¨ x ¸ 2 2 2 s c S L ©L ¹ 2 . We can evaluate the constants c1 and c2 using the boundary conditions u 0, t 0 U 0, s 0 U 1, s 0 and u 1, t give in turn c1 = 0 = c2. Therefore, U x, s As §S · sin ¨ x ¸ 2 2 2 s c S L ©L ¹ 2 . 0 Chapter 7 512 Taking the inverse Laplace transform, we have u x, t §Sc · §S · A cos ¨ t ¸ sin ¨ x ¸ . © L ¹ ©L ¹ Example 7.9. Solve the initial-boundary value problem wu x, t w 2 u x, t wt wx 2 , 0 x 2, t ! 0 with boundary and initial conditions u 0, t 0, u 2, t 0 u x,0 3sin 2S x . Solution: Taking the Laplace transform and applying the initial condition d 2U x, s dx 2 d 2U x, s dx 2 sU x, s u x,0 sU x, s 3sin 2S x This is an ordinary differential equation if U x, s is regarded as a function of x alone, s being a parameter. The transformed differential equation is a linear second-order ODE D 2 s U x, s 3sin 2S x Laplace Transform Methods for Partial Differential Equations (PDEs) 513 This is a differential form of a linear second-order ODE with constant coefficients. We solve it by finding the complementary function and particular integral where C.F is the general solution of the homogeneous problem C.F U h x, s c1 e s x c2 e s x and the particular integral is P.I P.I U Nh x, s 3 U Nh x, s 3 1 sin 2S x D2 s 1 2 4S s replace D 2 D2 a 2 4S 2 sin 2S x Now we have the general solution U x, s U h x, s U Nh x, s U x, s c1 e s x c2 e s x 3 1 4S 2 s sin 2S x . We can evaluate the constants c1 and c2 using the boundary condition u 0, t 0 U 0, s 0 and u 2, t 0 U 2, s 0 so we have U 0, s 0 c1 c2 and U 2, s 0 c1 e 2 s c2 e 2 s . Chapter 7 514 Solving for c1 and c2 we get c1 = 0 = c2. Therefore, U x, s 3 1 2 4S s sin 2S x . Taking the inverse Laplace transform, we have 2 3e 4S t sin 2S x . u x, t Example 7.10. Solve the initial-boundary value problem wu x, t w 2 u x, t wt wx 2 sin S x , 0 x 1, t ! 0 with boundary and initial conditions u 0, t 0, u 1, t u x,0 0, ut x,0 0 0. Solution: Taking the Laplace transform and applying the initial condition d 2U x, s dx 2 d 2U x, s dx 2 s 2U x, s s u x,0 ut x,0 s 2U x, s sin S x s . sin S x s Laplace Transform Methods for Partial Differential Equations (PDEs) This is an ordinary differential equation if U 515 x, s is regarded as a function of x alone, s being a parameter. The transformed differential equation is a linear second-order ODE D 2 s 2 U x, s sin S x s . This is a differential form of a linear second order ODE with constant coefficients. We solve it by finding the complementary function and particular integral, where C.F is the general solution of the homogeneous problem C.F U h x, s c1 e s x c2 e s x and the particular integral is P.I P.I U Nh x, s U Nh x, s 1 1 sin S x 2 s D s2 replace D 2 D2 1 1 sin S x s S 2 s2 Now we have the general solution U x, s U h x, s U Nh x, s U x, s c1 e s x c2 e s x 1 1 sin S x 2 s S s2 . a 2 S 2 Chapter 7 516 We can evaluate the constants c1 and c2 using the boundary condition u 0, t 0 U 0, s 0 and u 1, t 0 U 1, s so we have U 0, s 0 c1 c2 and U 1, s 0 c1 e s c2 e s Solving for c1 and c2, we get c1 = 0 = c2. Therefore, U x, s 1 1 sin S x 2 s S s2 Using partial fractions, we get U x, s º 1 ª1 1 « » sin S x S 2 « s S 2 s2 » ¬ ¼ Taking the inverse Laplace transform, we have u x, t 1 ª 1 º 1 sin S t » sin S x 2 « S ¬ S ¼ Thus, u x, t 1 ªS sin S t º¼ sin S x . S3 ¬ . 0 Laplace Transform Methods for Partial Differential Equations (PDEs) 517 Example 7.11. A very long cylindrical rod is placed along a positive x axis with one end at x 0. The rod is so long that any effect from its right end may be neglected. Its sides are covered with perfect insulation so that no heat can enter or escape there through. At time t 0 0, the temperature of the rod is 0 c throughout. Suddenly, the left end of the rod has its temperature raised to u0 and maintained at this temperature thereafter. The initial boundary-value problem describing temperature u wu x, t k wt w 2 u x, t wx 2 x, t at points in the rod is , 0 x 2, t ! 0 with boundary and initial conditions u 0, t u0 ; u x,0 0, k is a constant described as the thermal diffusivity of the material in the rod. Use Laplace transforms on the variable t to find where u x, t . Solution: Taking the Laplace transform and applying the initial condition k k d 2U x, s dx 2 d 2U x, s dx 2 sU x, s u x,0 sU x, s 0 . Chapter 7 518 This is an ordinary differential equation if U x, s is regarded as a function of x alone, s being a parameter. The transformed differential equation is a linear second-order homogeneous ODE § 2 s· ¨ D ¸ U x, s k¹ © 0 with the general solution U x, s c1 e s x k c2 e s x k . We can evaluate the constants c1 and c2 using the boundary condition u 0, t u0 U 0, s u0 s so we have U 0, s u0 s c1 c2 and require c1 = 0 to have U x, s o f as ݔ՜ ҄. Further, c1 0, c2 u0 s s U x, s u0 k x e s Taking the inverse Laplace transform, we have Laplace Transform Methods for Partial Differential Equations (PDEs) 519 § x · u0 erfc ¨ ¸. © 2 kt ¹ u x, t where erfc x is the complementary error function 1 erf x erfc x x 2 1 2 2 W ³ e dW f W 2 e dW . S ³ S 0 x Example 7.12. Use the Laplace transform method to find the solution of the modified wave equation w 2 u x, t wx c2 2 w 2 u x, t wt 2 2cO that remains finite for u x, 0 0 u 0, t sin t for t ! 0. and wu x, t wt O 2 u x, t t ! 0 and satisfies the initial conditions ut x, 0 0 and the boundary Solution: Taking the Laplace transform and applying the initial condition d 2U x, s dx 2 d 2U x, s dx 2 c 2 s 2U x, s 2cO sU x, s O 2U x, s 2 cs O U x, s 0 condition Chapter 7 520 This is an ordinary differential equation if U x, s is regarded as a function of x alone, s being a parameter. The transformed differential equation is a linear second-order homogeneous ODE D 2 cs O 2 U x, s 0 . This is a differential form of a linear second-order homogeneous ODE with constant coefficients. We solve it by finding the complementary function and particular integral where C.F is the general solution of the homogeneous problem C.F U h x, s c1 e cs O x c2 e cs O x c1 e cs O x c2 e cs O x U x, s (7.5) We can evaluate the constants c1 and c2 using the boundary condition u 0, t sin t U 0, s and require c1 = 0 to have U Further, c2 Thus, 1 s 1 2 1 c1 c2 s 1 2 x, s o f as ݔ՜ ҄. Laplace Transform Methods for Partial Differential Equations (PDEs) U x, s 1 e cs O x s 1 U x, s 1 ½ ­ e O x ® e cs x 2 ¾ s 1 ¿ . ¯ 521 2 Taking the inverse Laplace transform, we have u x, t e O x sin t cx u t cx . Summary In this chapter, we have described and explained the solutions of partial differential equations using the Laplace transform method: x The Laplace transforms of partial derivatives have been established and tabulated. The solutions of partial differential equations with various initial and boundary conditions have been explained with several examples. x The solutions of heat and wave equations have also been discussed with several examples. f t f t f t f t 3 4 5 f t 2 季 1 2 4cos 3t 5sin 3t e 2 t 3cosh 6t 8sinh 3t te 3t cos 2t e iwt 1 e 3t Ans Ans F s F s F s F s Ans Ans Ans F s 2 . 3s 24 . 2 s 36 s 9 4 s 23 . 2 s 4 s 13 2 s 2 6s 13 s 2 6s 5 1 2 1 . s s s6 s iw . s 2 w2 Find the Laplace transforms of the following functions. EXERCISES AND ANSWERS CHAPTER 8 § S· cos ¨ t ¸ © 6¹ f t f t 11 12 sin t sin 4t 5 f t 10 dW t 2 cos at W sin W sin at t 0 W ³e t t cos wt f t f t f t f t 9 8 7 6 Ans F s Ans F s F s F s F s F s Ans Ans Ans Ans Ans F s Exercises and Answers 2 . 3 . S 1 4s e . 2 s3 2 1 3s 1 . 2 s2 1 4 cos 5 s sin 5 . s 2 16 s2 a2 2 s s 2 3a 2 §a· tan 1 ¨ ¸ . ©s¹ cot 1 s 1 . s s 2 w2 s 2 w2 523 17 f t f t f t 15 16 f t Chapter 8 0dt da ; f t 2a a d t d 2a with ­2 0 d t 1 ° ®1 1 t d 3 °0 3 t d 4 ¯ a t with f t b b with ­3 0 d t 1 ® ¯1 1 t d 2 f t f t . f t . f t f t4 f t2 f t Ans Ans Ans Ans Ans F s F s F s F s F s aª1 1 º « bs ». s « bs e 1 » ¬ ¼ 1 2 e s e3s 4 s s 1 e 1 3 2e s e2 s 2 s s 1 e 1 . s 1 2 K § as · tanh ¨ ¸ . s © 2¹ Find the Laplace transforms of the following periodic functions. sin t with f t 2S ­K f t ® ¯ K 14 13 524 22 21 20 19 18 f t f t f t T f t f t T 2 T dt dT 2 with 0dt Ans Ans Ans F s F s F s 2 tan Ts . 4 Ts 2 1 . s 1 1 e S s 2 1 coth S s . 2 s 1 2 ­t ® ¯0 0 d t d1 t !1 sin 2t u t S Ans Ans F s F s 1 e s s 1 e . s2 s 2e S s . s2 4 Find the Laplace transforms of the following functions by expressing in to unit step function. f t . ­ 2t °° T ® °2 ¨§1 t ¸· °¯ © T ¹ f t . ­ I m sin t 0 d t S ® S d t d 2S ¯0 with sin t with f t S f t 2S f t f t Exercises and Answers 525 27 26 25 24 23 526 f t f t f t f t f t 0 d t d1 1 t d 2 t!2 Ans Ans ­1 0 d t 1 ° ®2 1 t d 4 °1 t!4 ¯ ­2 t ° ®6 °t 4 ¯ Ans Ans Ans ­0 0 d t 1 ° ®1 1 t d 3 °2 t !3 ¯ ­°e t 0 d t d1 ® 2t t !1 °̄e ­sin t 0 t 2S ® t ! 2S ¯0 Chapter 8 F s 1 1 e s e 4 s s 1 s e e 3 s s 2 1 1 e 2S s . s 1 s 1 e s 2 °½ °­1 e ® ¾. s 2 °¿ °¯ s 1 2 1 s § 3 1 · 3s § 1 1 · e ¨ ¸ e ¨ ¸. s s2 © s s2 ¹ © s s2 ¹ F s F s F s F s 34 33 32 31 30 29 28 F s F s F s F s F s F s F s 2 2 3s . 12s 48s 36 3 1 s s 1 s6 s 4 s 1 s 2 36 s s 1 s2 9 2 s 1 s 1 4s 1 2s . 2 s 4s 5 e 2S s . s s2 1 Ans f t f t f t f t f t f t f t Ans Ans Ans Ans Ans Ans 3 3t 1 t e e. 8 8 et 1 t 1 2 t . 2 1 4t 7 t 4 2t e e e . 15 5 3 9 1 4 cos t cos3t. 2 2 et e t 2tet . e2t 5sin t 2cos t . 1 cos t u t 2S . Find the inverse Laplace transforms of the following functions. Exercises and Answers 527 F s 39 41 F s F s F s 38 40 F s F s F s 37 36 35 528 6 2 f t f t § s 1 · log ¨ ¸ © s 1 ¹ 6 s 2 50 s 3 s2 4 Ans Ans f t f t f t f t Ans s2 6 s2 1 s2 4 s2 1 Ans f t Ans Ans Ans 2 s3 s 1 s 2 3s 2 1 s 1 s 4 2 2s s2 s3 s6 Chapter 8 1 t sin t. 2 8e3t 2cos 2t 3sin 2t. 2sinh t . t 5 1 sin t sin 2t. 3 3 cos t e2t et tet . 2sin t 2sin 2t. e 2 t 2e 3 t e 6 t . 45 45 44 43 42 F s F s F s F s F s 1 . s s7 s2 . s 2s 1 2 s2 . s s2 2 Ans Ans f t f t 9t 2 2 2cosh 3t. 2 cos t t 2 2. Ans Initial value Ans Initial value Ans Initial value 0, final value 1, final value 0, final value Find the initial and final values of the functions using the initial and final value theorem. 162 3 s s2 8 2 s3 s 2 1 Exercises and Answers 1 7 0 f 529 52 51 50 49 48 47 530 t 1 the solution 2 2 2 2 s s2 a 1 s O 2 1 s2 s2 1 of s 1 s 3 1 1 s s 1 the 1 integro-differential dy y W cos t W dW 0, y 0 dt ³0 Find F s F s F s F s F s equation Ans Ans Ans Ans Ans Ans y t f t f t f t f t f t 1 1 2 t . 2 2 2cos at at sin at . 2a 4 sin Ot Ot cos Ot . 2O 3 t sin t . 1 3t t e e . 4 et 1. Evaluate the inverse Laplace transforms of the following functions using the convolution theorem. Chapter 8 58 57 56 55 0 7 dt dc t dt dy t 4y t W 6c t 2y t x t 1 Ans Ans y t i t C § 1 · sin ¨ t¸ L © LC ¹ dt du t dt dx t 11u t . x t . dt 2 d 2c t H s H s Ans Ans Ans Ans H s 6 dt dc t C s U s Y s X s s 11 dt du t . . u t . s 7s 6 2 s2 s 2 s 1 2c t 2 Y s X s 1 . s4 2 t 3et tet . V Find the transfer function of the following differential equations ³ t W e dW 0, y 0 t Find the DE corresponding to the transfer function dt 2 dc t 2 dt 2 d y t 2 dt dy t dy y dt Find the solution of the integro-differential equation 1 54 t di 1 L ³ i W dW V , i 0 dt C 0 53 Find the solution of the integro-differential equation Exercises and Answers 531 2s 1 y 0 1 & y' 0 1 8et sin 2t y '' t 2 y ' t 5 y t 4 with 62 y 0 1 & y' 0 9e2t y 5 y '' 2 y ' 8 y sin t with y 0 with ''' 6 8sin 2t 3 & y' 0 y '' t 4 y t y 0 . Chapter 8 y ' 0 , y '' 0 with 1 2t 1 cos 2t 3sin 2t et 3t 2 e 2t . 1 t 2 2t 8 4t e e e 3 15 85 y t y t y t 2t 1 et cos 2t. 1 cos t 13sin t 170 Ans y t Ans Ans Solve the following differential equations using the Laplace transform. s 6s 2 2 y '' t y ' t 2 y t H s 61 60 59 532 67 66 65 64 63 6 & y' 0 1 & y' 0 2 1 & y ' 0 L 2 0 4e t 2 e t G t 2 et u t 2 54te2t AG t t0 , i 0 1 & y' 0 di Ri dt y 0 y '' t 2 y ' t y t y 0 y '' t 5 y ' t 6 y t y 0 1 0 y '' t 3 y ' t 2 y t y 0 y '' t y ' t 2 y t with with with with Exercises and Answers i t y t Ans Ans u t2 . A e L L R t t0 u t t0 . et t 2 5t 2 et . y t 3e3t 4e2t e2 t 2 e3 t 2 u t 2 . 2 t 1 6et 9t 2 6t 1 e2t . y t e 2 t 1 t et e y t Ans Ans Ans 533 72 71 70 69 68 534 wt . Find the 0 x' 0 x t 2 § w · f0 sin w0t sin wt ¸ . 2 ¨ m w w0 © w0 ¹ Ans 0&x 0 0 y 0 0&x 0 4 2x 2 y dx dy 2 x y 2e t ; 4 z 2 y 4e 2 t dt dt and dz x z; y 0 3, x 0 9& z 0 1 dt with dx dy 2 x 2 y 16tet ; dt dt y 0 dx dy 2 x 5 y 5et cos t ; x 2 y 10et sin t dt dt with y t 2et 4t 3 2e3t 8e2t 5et 1 cos t sin t 5et 1 cos t 6t 1 4e3t 8et 8e3t 3t 1 et e 2t 2e3t . 3t 2 2et 3e2t 8e3t . y t z t x t Ans et 12t 13 e3t 16e2t . Ans x t y t x t Ans . Solve the following simultaneous differential equations using the method of Laplace transform. x 0 force and one with the frequency w0 of the free oscillator, assuming displacement as a function of time. Notice that it is a linear combination of two simple harmonic motions, one with the frequency of the driving An undamped oscillator is driven by force f 0 sin Chapter 8 75 74 73 dz dt 8&z 0 2 y 3z, 8&z 0 3. t, x 3. with dy y dt 2 y z 1 with d2y dy 4 10 y x 2 dt dt Find the impulse response of the system described by the differential equation y 0 dx dy 2 2y dt dt y 0 dy dt Exercises and Answers h t y t Ans z t Ans 3e4t 5et 6t 3 3 2t 1 e t 4 4 2 3 3 2t 1 e t 4 4 2 1 2t e sin 6 x t 5et 2e4t . y t 535 78 77 76 536 wu x, t 0, ux 0, t x of 1 and lim ux x, t wx 2 wt u x,0 w 2 u x, t wu x, t 0. 0. 0, x ! 0, t ! 0 0 lim u x x, t u 0, t x of 0 g, 5. 0, x ! 0, t ! 0 wx 2 ut x, 0 and w 2 u x, t wx 3, u 0, t 2 wt 2 u x, 0 w 2 u x, t wt u x, 0 wu x, t with with Solve following initial-boundary value problem Chapter 8 Ans u x, t Ans Ans u x, t 0 ³ t 2 1 4xW e dW . SW x ct x t ct § x· 3 2H ¨ t ¸ . © 2¹ ­ gt 2 °° 2 ® ° g x 2 2cxt °̄ 2k 2 u x, t BIBLIOGRAPHY 1. Shaila Dinkar Apte. (2016) Signals and systems: principles and applications, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-1-107-14624-2 2. Won Y. Yang et al. (2009) Signals and Systems with MATLAB. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Heidelberg, ISBN 978-3-540-92953-6. 3. Edsberg, Lennart. (2016) Introduction to computation and modeling for differential equations. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey, ISBN 978-1-119-01844-5 4. Shima H., Nakayama T. (2009) Laplace Transformation. In Higher Mathematics for Physics and Engineering. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/b138494_13 5. Michael Corinthios. (2009) Signals, systems, transforms, and digital signal processing with MATLAB CRC Press, 978-1-4200-9048-2. 6. Chi-Tsong Chen. (2004) Signals and systems. Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-515661-7 7. Paul Blanchard. (2012) Differential Equations, Cengage Learning, 1133109039. 8. Lennart Edsberg. (2015) Introduction to Computation and Modeling for Differential Equations, John Wiley & Sons, 1119018463.