Milgram's Obedience & Cognitive Theories: Psychology Insights

advertisement

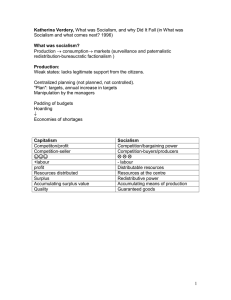

1.Explaining Milgram’s Findings Stanley Milgram’s obedience experiments, conducted in the 1960s, revealed profound insights into human behavior under the influence of authority. Inspired by Solomon Asch’s studies on social conformity, Milgram set out to understand how social pressures could lead individuals to act against their personal morals and values. His findings not only shaped the field of social psychology but also sparked enduring ethical debates. Milgram's experiment involved participants who believed they were administering electric shocks to a “learner” for incorrect answers in a learning task. In reality, the “learner” was an actor, and no shocks were delivered. Participants, labeled as "teachers," were instructed by an authority figure in a lab coat to increase the shock intensity after each incorrect response. As the shocks escalated, the “learner” exhibited signs of extreme distress, even pleading for the experiment to stop. Despite this, a significant 65% of participants obeyed instructions to deliver the maximum shock of 450 volts. Milgram’s research demonstrated that ordinary individuals could commit acts they found morally reprehensible under the influence of authority. His experiment challenged the notion that only inherently "evil" individuals commit atrocities. Instead, Milgram argued that situational factors, such as the presence of a legitimate authority figure, play a critical role in shaping behavior. One key finding was the impact of proximity on obedience. When participants could not see or hear the “learner,” obedience was highest. As proximity increased, obedience rates decreased. For example, in conditions where participants had to physically place the “learner’s” hand on a shock plate, obedience dropped to 18%. This highlights the role of emotional detachment in facilitating harmful actions. Milgram also observed significant psychological stress among participants. Many exhibited nervous laughter, sweating, or trembling. Interestingly, these reactions were not signs of cruelty but of extreme discomfort. After the experiment, participants often rationalized their actions by shifting responsibility to the authority figure, entering what Milgram termed the “agentic state.” In this state, individuals view themselves as instruments carrying out another’s wishes, thus absolving themselves of personal accountability. Milgram’s findings have profound implications for understanding historical events, such as the Holocaust. He drew parallels between his experiments and Hannah Arendt’s concept of the "banality of evil," which emerged from her analysis of Adolf Eichmann’s trial. Arendt described Eichmann not as a sadistic monster but as an ordinary bureaucrat following orders. Similarly, Milgram’s subjects, ordinary people from diverse backgrounds, demonstrated how authority could override personal ethics. Critics, however, have pointed out limitations in Milgram’s paradigm. For instance, his focus on obedience under experimental conditions does not fully account for the complex motivations behind real-world atrocities, such as ethnic hatred or socioeconomic factors. Additionally, about 35% of participants resisted authority, suggesting that personal dispositions and values can also play a significant role in decision-making. Despite its limitations, Milgram’s work remains a cornerstone in psychology, offering valuable insights into the power of authority and situational forces. It underscores the need for vigilance in hierarchical systems and highlights the potential for ordinary individuals to commit extraordinary acts—whether good or evil—depending on the circumstances. 2. What Is the Difference Instrumental Beliefs? Between Philosophical and Beliefs play a crucial role in shaping how individuals, particularly leaders, perceive and interact with the world. Alexander George's concept of the "operational code" provides a framework for understanding these beliefs, categorizing them into two distinct types: philosophical beliefs and instrumental beliefs. These categories help distinguish between a leader’s worldview and their approach to achieving goals. Philosophical beliefs address fundamental questions about the nature of political life and the broader universe in which individuals operate. These beliefs involve one's perspective on whether the political world is inherently harmonious or conflictual, the predictability of historical developments, and the extent of human agency in shaping history. Leaders’ philosophical beliefs often align with traditional political theories, such as those of Hobbes and Locke. For instance, Hobbes famously viewed human nature as brutish and political life as a constant struggle for survival, while Locke held a more optimistic view, seeing the world as inherently cooperative. These beliefs frame how leaders diagnose situations, understand opponents, and set longterm goals. In contrast, instrumental beliefs focus on the practical aspects of achieving political objectives. These beliefs guide leaders in selecting strategies, assessing risks, and determining the most effective timing and means to accomplish their goals. Instrumental beliefs are rooted in action—they are about how leaders navigate challenges and implement their decisions in specific contexts. For example, Lyndon B. Johnson’s instrumental beliefs shaped his approach to the Vietnam War. He relied on bargaining backed by threats, reflecting his broader strategy of controlling risks through a "graduated bombing" campaign. While his philosophical belief in a conflictual world aligned with Hobbesian views, his instrumental beliefs dictated the specific steps he took to address challenges. The distinction between these two belief types highlights their complementary roles in decision-making. Philosophical beliefs provide a leader’s overarching worldview, setting the stage for how they perceive and prioritize issues. Instrumental beliefs, on the other hand, translate this worldview into actionable strategies. Both categories are crucial for understanding why leaders make particular decisions and how they justify their actions. Operational code analysis, the framework developed to study these beliefs, emphasizes their importance in explaining variations in leadership behavior. Leaders with similar philosophical beliefs may differ significantly in their instrumental beliefs, leading to diverse approaches to identical challenges. For instance, while two leaders might view the world as fundamentally conflictual, their methods for addressing conflict—diplomacy versus military action—might differ due to variations in their instrumental beliefs. In conclusion, the difference between philosophical and instrumental beliefs lies in their focus and application. Philosophical beliefs shape a leader’s understanding of the political environment, while instrumental beliefs dictate the strategies they employ to achieve their objectives. Together, they offer a comprehensive framework for analyzing political decision-making and understanding the interplay between a leader’s worldview and their practical actions 3.What are the similarities and differences between attribution and schema theory? Attribution theory and schema theory are both cognitive frameworks used to understand how individuals interpret and organize information about the world around them. While they share some similarities in terms of cognitive efficiency and their implications for decision-making, they differ in their fundamental focus and applications. Attribution theory posits that individuals act as "naive scientists," constantly seeking to uncover the causes behind their own behavior and that of others. This theory distinguishes between situational and dispositional attributions when explaining behavior. Situational attributions assign behavior to external factors, whereas dispositional attributions link behavior to internal characteristics of the person. A common pitfall of attribution theory is the fundamental attribution error, where people tend to overemphasize dispositional factors when evaluating others while attributing their own actions to situational influences. Attribution theory highlights the cognitive shortcuts, such as the representativeness and availability heuristics, that individuals use to simplify complex causal reasoning. These heuristics often lead to biased judgments based on stereotypes or recent experiences rather than objective data. On the other hand, schema theory conceptualizes individuals as "cognitive misers" who categorize and label information to efficiently manage cognitive overload. Schemas are mental frameworks or stereotypes stored in memory that help people interpret and predict new experiences based on prior knowledge. Unlike attribution theory, which focuses on causality, schema theory emphasizes classification and inference. People use schemas to assimilate new information into pre-existing categories, enabling them to make quick judgments with minimal cognitive effort. However, like attribution errors, schemas can lead to cognitive biases and errors when individuals misapply or rely too heavily on these mental shortcuts, resulting in stereotyping and incorrect inferences. Despite their differences, both theories acknowledge that human cognitive capacity is limited, and thus, people rely on heuristics and mental shortcuts to navigate their environments. They also both recognize the potential for error in human reasoning. In political psychology, attribution theory explains how policymakers attribute the actions of rival states to either situational or dispositional factors, which can influence foreign policy decisions. Similarly, schema theory explains how political actors and voters use preconceived categories to evaluate candidates or interpret political events, sometimes leading to misjudgments. The primary distinction between the two lies in their respective focuses. Attribution theory is concerned with understanding "why" events or behaviors occur, focusing on causal explanations. In contrast, schema theory is more about "how" information is organized and processed through mental structures that guide perception and action. In conclusion, while attribution and schema theories both provide valuable insights into cognitive processing and decision-making, they approach the problem from different angles. Attribution theory explains how people seek causes for behaviors and events, while schema theory describes how information is structured and used for interpretation. Together, they offer a comprehensive understanding of how people perceive and respond to the world around them. 4.compare and contrast Janis’ Groupthink with NewGroup Syndrome Janis' Groupthink and NewGroup Syndrome are both theories that examine the potential dysfunctions in group decision-making, yet they approach the issue from different perspectives and contexts. While both theories focus on conformity and flawed decision-making processes, they differ in their antecedent conditions, symptoms, and implications. Groupthink, a concept developed by Irving Janis in his seminal work, refers to a phenomenon where cohesive groups prioritize unanimity over critical evaluation of alternative courses of action. According to Janis, groupthink occurs when a highly cohesive group is insulated from outside perspectives, lacks procedural norms, and operates under directive leadership. These factors lead to symptoms such as the illusion of invulnerability, collective rationalization, self-censorship, and pressure to conform. Classic examples of groupthink include the failed Bay of Pigs invasion and the escalation of the Vietnam War, where decision-makers suppressed dissenting views and failed to critically analyze flawed strategies. One key aspect of groupthink is the overemphasis on consensus, leading to faulty decisions that overlook potential risks and alternative solutions. The presence of mindguards—group members who shield the leader from dissenting information— further exacerbates the issue by reinforcing a false sense of unanimity. Janis emphasized that groupthink tends to occur in groups with long-standing cohesion, shared values, and a preference for maintaining harmony over objective analysis. In contrast, NewGroup Syndrome, introduced by Eric Stern and Bengt Sundelius, focuses on the unique challenges faced by newly formed groups, particularly in policy and crisis decision-making contexts. Unlike groupthink, which typically affects established groups with strong cohesion, NewGroup Syndrome occurs in groups that lack established norms, trust, and clear roles. The absence of a shared subculture and procedural guidelines creates uncertainty, making group members more susceptible to conformity pressures and overreliance on assertive leaders. NewGroup Syndrome suggests that newly formed groups experience high levels of anxiety and dependence, leading to excessive deference to authority figures and a reluctance to voice independent opinions. This dynamic results in similar symptoms to groupthink, such as conformity and limited critical evaluation, but arises from different origins. Instead of the cohesion-driven conformity seen in groupthink, NewGroup Syndrome is driven by uncertainty and the need for stability in an unfamiliar environment. The differences between these two theories lie primarily in the group dynamics and developmental stages. Groupthink thrives in mature, cohesive groups with a strong desire for agreement, whereas NewGroup Syndrome is more likely to occur in groups that are still in the formative stage, lacking the procedural clarity and experience necessary for effective decision-making. Additionally, the leadership dynamics in each context differ: in groupthink, leaders reinforce conformity through dominance, while in NewGroup Syndrome, leaders become de facto decisionmakers due to the group's uncertainty. Despite their differences, both theories underscore the importance of critical thinking, open communication, and procedural safeguards to prevent flawed decision-making. Strategies such as encouraging dissent, seeking external perspectives, and establishing clear decision-making protocols can help mitigate the risks associated with both groupthink and NewGroup Syndrome. In conclusion, while Janis' Groupthink and NewGroup Syndrome both highlight the dangers of conformity in group settings, they arise from different conditions and affect groups at different stages of development. Recognizing the distinctions and overlaps between the two theories is crucial for understanding and improving group decision-making processes in various organizational and political contexts. 5.List three main theories on aging. What does each one of them emphasize? Aging is a complex process that can be understood through various sociological theories. Three main theories on aging are disengagement theory, activity theory, and continuity theory. Each of these theories emphasizes different aspects of aging and offers unique perspectives on how individuals adapt to later life. Disengagement theory, one of the earliest theories of aging within the functionalist perspective, suggests that withdrawing from society and social relationships is a natural part of growing old. This theory posits that as people age, they experience a gradual withdrawal from social roles and relationships due to physical and mental decline. The theory emphasizes that this withdrawal is mutually beneficial: it allows society to function smoothly by making way for younger generations while also giving elderly individuals the freedom to focus on their personal development without societal pressures. However, disengagement theory has faced criticism for its assumption that all elderly individuals experience aging in the same way and that social withdrawal is inevitable. Activity theory, developed as a response to disengagement theory, emphasizes that staying socially and physically active is crucial for successful aging. According to this theory, older adults who remain engaged in social, physical, and cognitive activities are more likely to maintain their well-being and life satisfaction. The theory argues that maintaining roles and activities from earlier stages of life helps individuals cope with aging and provides them with a sense of purpose. Critics of activity theory point out that it does not account for individuals who may find fulfillment in solitude or have limited access to social opportunities due to economic or health-related constraints. Continuity theory, another perspective within the functionalist approach, emphasizes the importance of maintaining consistency in lifestyle, relationships, and behaviors as individuals age. This theory suggests that people develop internal and external structures throughout their lives, such as personality traits and social roles, which they seek to maintain even in old age. By making adaptive choices that align with their past experiences and identities, older adults can achieve a sense of stability and well-being. The continuity theory highlights the role of personal choice in the aging process and suggests that individuals can shape their experiences of aging based on their lifelong habits and preferences. However, critics argue that the theory may overlook the impact of external factors such as health issues and social changes that can disrupt continuity. In conclusion, disengagement theory, activity theory, and continuity theory each provide valuable insights into the aging process. While disengagement theory emphasizes the natural withdrawal from society, activity theory stresses the benefits of continued engagement, and continuity theory highlights the importance of maintaining lifelong patterns. Understanding these theories allows for a more comprehensive view of aging and helps to inform policies and practices that support the well-being of older adults. 6.The Two Main Theories Explaining Global Wealth and Poverty Global disparities in wealth and poverty are shaped by numerous factors, but two principal theories dominate discussions: modernization theory and dependency theory. Each offers a distinct perspective on the causes and persistence of inequality. Modernization Theory Modernization theory attributes global inequality to differences in technological and cultural advancements between nations. Rooted in Western-centric views, this theory suggests that underdeveloped nations are in earlier stages of a linear progression toward industrialization and prosperity. Proponents argue that poor countries remain impoverished due to internal challenges, such as lack of infrastructure, ineffective governance, and traditional societal values that hinder economic growth. Under this framework, wealthier nations serve as models for economic development. By adopting modern economic policies, technological advancements, and education systems, developing nations can theoretically replicate the success of industrialized countries. This perspective supports initiatives like foreign aid, international trade, and investment, which are believed to accelerate modernization and integration into the global economy. However, critics argue that modernization theory oversimplifies complex issues by ignoring historical and structural factors. It also often promotes a one-size-fits-all approach that overlooks cultural diversity and the unique challenges faced by different nations. The assumption that Western methods and ideologies are universally applicable has been widely contested. Dependency Theory Dependency theory offers a contrasting view, emphasizing the structural inequalities inherent in the global economic system. According to this theory, poverty in developing nations results from their exploitation by wealthier countries. Historically, colonialism established unequal trade relationships, extracting resources from colonies while limiting their industrial development. This imbalance has persisted in modern times through neocolonial practices, such as unequal trade agreements, exploitative multinational corporations, and debt dependency. The theory categorizes nations into "core," "periphery," and "semi-periphery" states. Core nations, typically wealthy and industrialized, dominate global markets, extracting resources and labor from periphery nations, which are predominantly poor and reliant on exporting raw materials. Semi-periphery nations occupy an intermediary position, often exploited by core nations while exerting influence over periphery states. Dependency theorists argue that this system creates a cycle of underdevelopment. Peripheral nations remain trapped in a subordinate position, reliant on exports with low added value, while importing expensive manufactured goods from core nations. Structural adjustments imposed by international financial institutions, like austerity measures, often exacerbate these inequalities. While dependency theory highlights the role of external forces in perpetuating poverty, it has been criticized for its deterministic outlook. It underestimates the agency of developing nations and the potential for internal reforms to break the cycle of dependency. Conclusion Modernization and dependency theories offer contrasting explanations for global wealth and poverty. Modernization theory focuses on internal development and progress through imitation of industrialized nations, while dependency theory emphasizes external exploitation and systemic inequality. Both theories provide valuable insights but also have limitations, underscoring the complexity of addressing global poverty and inequality. Combining elements of both perspectives might offer a more holistic understanding and pave the way for effective solutions. 7.State Socialism with Central Planning vs. Market Socialism Socialism, as an economic system, advocates for the shared ownership of resources and production. However, its application varies significantly, with state socialism and market socialism representing two distinct approaches. Both systems aim to achieve economic equality, yet they differ in mechanisms and outcomes. State Socialism with Central Planning State socialism is characterized by government ownership and centralized control over production and distribution. In this system, central authorities make decisions regarding what goods and services to produce, their quantity, and their price. This approach aims to eliminate economic inequality by ensuring that resources are distributed according to societal needs rather than market demand. Countries like the former Soviet Union, China, and North Korea exemplify state socialism. Under these regimes, the government exerts extensive control, often dictating business operations and resource allocation. The focus is on collective welfare, with profits and benefits distributed among all citizens. However, the rigidity of central planning often results in inefficiencies. For instance, overproduction of unwanted goods and underproduction of essential items are common due to the lack of market feedback mechanisms. Critics argue that state socialism stifles innovation and economic growth. The absence of competition and profit incentives often discourages efficiency and creativity. Furthermore, bureaucratic inefficiencies and corruption can exacerbate economic challenges, as decision-making is concentrated in the hands of a few. Market Socialism Market socialism represents a blend of socialist principles and market mechanisms. Unlike state socialism, market socialism allows limited private ownership and incorporates market forces to guide production and pricing decisions. Governments still play a significant role, but they do not control every aspect of the economy. In market socialism, businesses can respond to consumer demand, fostering innovation and efficiency. Profits generated are often reinvested into public funds or distributed among workers rather than being concentrated in the hands of a few owners. This approach seeks to combine the efficiency of capitalism with the equity of socialism. Countries transitioning from central planning to market-oriented systems, like Vietnam and certain Eastern European nations, illustrate this model. These nations have retained socialist ideals while embracing elements of market economies to stimulate growth. For example, small businesses may operate privately, while major industries, such as utilities or healthcare, remain under government control. Critics of market socialism point to its potential to widen inequalities. The reliance on market dynamics can lead to disparities in wealth and income, challenging the socialist goal of complete equity. Additionally, striking a balance between market freedom and governmental regulation remains a persistent challenge. Conclusion State socialism and market socialism differ in their approaches to resource allocation and economic management. While state socialism emphasizes centralized planning and collective welfare, market socialism incorporates market mechanisms to enhance efficiency and innovation. Both systems aim to reduce economic inequality but face unique challenges. The choice between these models often depends on a society's historical, cultural, and economic context. Understanding their differences provides valuable insights into the diverse ways nations seek to achieve social and economic equity. 8.State Socialism with Central Planning vs. Market Socialism Socialism, as an economic system, advocates for the shared ownership of resources and production. However, its application varies significantly, with state socialism and market socialism representing two distinct approaches. Both systems aim to achieve economic equality, yet they differ in mechanisms and outcomes. State Socialism with Central Planning State socialism is characterized by government ownership and centralized control over production and distribution. In this system, central authorities make decisions regarding what goods and services to produce, their quantity, and their price. This approach aims to eliminate economic inequality by ensuring that resources are distributed according to societal needs rather than market demand. Countries like the former Soviet Union, China, and North Korea exemplify state socialism. Under these regimes, the government exerts extensive control, often dictating business operations and resource allocation. The focus is on collective welfare, with profits and benefits distributed among all citizens. However, the rigidity of central planning often results in inefficiencies. For instance, overproduction of unwanted goods and underproduction of essential items are common due to the lack of market feedback mechanisms. Critics argue that state socialism stifles innovation and economic growth. The absence of competition and profit incentives often discourages efficiency and creativity. Furthermore, bureaucratic inefficiencies and corruption can exacerbate economic challenges, as decision-making is concentrated in the hands of a few. Market Socialism Market socialism represents a blend of socialist principles and market mechanisms. Unlike state socialism, market socialism allows limited private ownership and incorporates market forces to guide production and pricing decisions. Governments still play a significant role, but they do not control every aspect of the economy. In market socialism, businesses can respond to consumer demand, fostering innovation and efficiency. Profits generated are often reinvested into public funds or distributed among workers rather than being concentrated in the hands of a few owners. This approach seeks to combine the efficiency of capitalism with the equity of socialism. Countries transitioning from central planning to market-oriented systems, like Vietnam and certain Eastern European nations, illustrate this model. These nations have retained socialist ideals while embracing elements of market economies to stimulate growth. For example, small businesses may operate privately, while major industries, such as utilities or healthcare, remain under government control. Critics of market socialism point to its potential to widen inequalities. The reliance on market dynamics can lead to disparities in wealth and income, challenging the socialist goal of complete equity. Additionally, striking a balance between market freedom and governmental regulation remains a persistent challenge. Conclusion State socialism and market socialism differ in their approaches to resource allocation and economic management. While state socialism emphasizes centralized planning and collective welfare, market socialism incorporates market mechanisms to enhance efficiency and innovation. Both systems aim to reduce economic inequality but face unique challenges. The choice between these models often depends on a society's historical, cultural, and economic context. Understanding their differences provides valuable insights into the diverse ways nations seek to achieve social and economic equity. 9.Discuss the Differences Between a Mass and a Crowd Collective behavior is a sociological concept that examines noninstitutionalized group actions. Two key forms of this behavior are masses and crowds, which, though similar in involving collective participation, differ significantly in their structure, proximity, and purpose. Definition and Characteristics A crowd is defined as a large number of people gathered in close physical proximity. Examples include concertgoers, protest participants, or worshippers at a religious service. Sociologists classify crowds into four types: casual crowds, which involve individuals present in the same space without meaningful interaction (e.g., people waiting in line); conventional crowds, such as attendees of a regularly scheduled event; expressive crowds, like those at funerals or weddings, where emotions are shared; and acting crowds, united by a specific goal, such as a protest or riot. In contrast, a mass consists of a large group of people sharing a common interest or goal but dispersed geographically. Members of a mass do not need to interact or be in close proximity. For instance, players of an online game or followers of a social media movement constitute a mass. Their connection is often mediated through technology rather than face-to-face interaction. Differences The primary distinction between a crowd and a mass lies in proximity and interaction. Crowds require physical closeness and direct interaction among members, creating an immediate and dynamic environment. Behavior in crowds is often influenced by emergent norms, which evolve as individuals respond to the collective situation. For instance, during a protest, norms around chanting or movement might develop spontaneously. Masses, on the other hand, are more diffuse. Interaction within a mass is often indirect and mediated by communication tools, such as social media platforms. Unlike crowds, masses are not restricted by location, allowing their influence and participation to span across regions or even continents. This lack of proximity also means that masses tend to share common interests, like a fandom or advocacy for a political cause, rather than direct experiences. Shared Traits Despite their differences, masses and crowds share commonalities. Both represent collective behavior, which occurs outside institutionalized frameworks. Members of crowds and masses often develop a sense of unity or solidarity, driven by shared interests or experiences. Moreover, both forms of collective behavior can lead to significant social outcomes, such as protests evolving into social movements or online campaigns influencing public opinion. Examples An example of a crowd is the attendees of a protest march, where individuals physically gather to express their views. A mass example is the participants of a global online petition advocating for climate change action. While the former relies on physical assembly, the latter leverages technology to create a shared platform for advocacy. Conclusion Crowds and masses are distinct yet interconnected phenomena within collective behavior. Crowds thrive on immediate, face-to-face interactions, while masses rely on shared interests across distances. Understanding their differences and similarities enriches our comprehension of human social dynamics and their capacity to drive change. 10.Is modernization Good or Bad? Modernization, often described as the process of transforming societies from traditional to industrial and technologically advanced, is a contentious topic. While it has propelled humanity forward in numerous ways, it is not without its drawbacks. The benefits and challenges of modernization can be better understood by examining its impact on technology, social institutions, population, and the environment. The Pros of Modernization One of modernization's most visible outcomes is technological advancement. Innovations such as the internet, electricity, and transportation have transformed daily life, making tasks more efficient and enabling global communication. For instance, crowdsourcing platforms like Kickstarter and Wikipedia illustrate how technology can harness collective intelligence, foster creativity, and drive societal progress. In disaster relief, modern tools have saved countless lives by efficiently organizing resources and responses, as seen in the aftermath of the Haitian earthquake and the Japanese tsunami. Social institutions have also evolved with modernization, adapting to changing societal needs. Industrialization, for instance, shifted economies from agrarian to urban-centric, leading to smaller family sizes and reshaping education systems. Modern medicine has improved health outcomes, increasing life expectancy and reducing mortality rates. These developments underline the transformative potential of modernization. The Drawbacks of Modernization Despite its advantages, modernization presents significant challenges. Technological dependence has created vulnerabilities, such as cyber risks, privacy concerns, and systemic failures during disasters. Events like the Fukushima nuclear disaster highlight the fragility of modern systems. Furthermore, modernization can exacerbate inequality, creating a "digital divide" between those with access to technology and those without, both within and between nations. Socially, modernization sometimes disrupts cultural identities. The push toward urbanization and industrialization often overlooks the importance of preserving traditions, creating tension between progress and cultural preservation. Moreover, the constant connectivity facilitated by technology has blurred work-life boundaries, leading to stress and burnout. Population dynamics further complicate modernization. In developed nations, aging populations strain social services, while in less developed areas, rapid population growth stresses limited resources. Both scenarios highlight the need for balanced approaches to modernization that consider demographic realities. Environmental Consequences Perhaps the most significant downside of modernization is its environmental impact. Industrialization and technological advances have increased resource consumption and pollution, contributing to climate change. Rising population levels compound these issues, leading to habitat destruction and species extinction at unprecedented rates. The challenge lies in modernizing sustainably, ensuring technological and economic growth do not come at the planet's expense. Conclusion Modernization is neither wholly good nor bad—it is a complex force with both positive and negative consequences. While it has driven technological innovation, improved living standards, and transformed societies, it has also created inequalities, environmental challenges, and cultural tensions. A balanced approach that prioritizes sustainability, equity, and cultural preservation is essential for ensuring modernization benefits all without undermining the future.