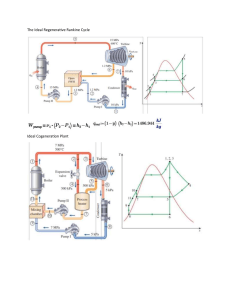

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/268472741 Energy Modelling of District Cooling Plant in Egypt Conference Paper · July 2013 DOI: 10.2514/6.2013-3943 CITATIONS READS 0 2,889 4 authors, including: E.E. Khalil Hesham Safwat Cairo University British University in Egypt 458 PUBLICATIONS 1,825 CITATIONS 15 PUBLICATIONS 24 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE All content following this page was uploaded by Hesham Safwat on 07 June 2016. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. SEE PROFILE ` DISTRCIT COOLING ENERGY AND ECONOMIC ANALYSIS Eng.Hesham M. Safwat, M. ASHRAE and Prof.Dr. Mahmoud A. Fouad, M. ASHRAE Faculty of Engineering, Cairo University, Cairo/Egypt, Hesham_Safwat@yahoo.com ABSTRACT Energy saving is the main concern nowadays, lack of energy is the future nightmare, the Design trend of district cooling plants is one HVAC green systems of saving energy but to apply this trend efficiently we should fully study the district cooling plants energy and economic analysis as they respond with the building and weather profiles , The research model investigates different variables affecting the energy consumption of the district cooling plant which are Changing the district cooling plant configuration, type of district cooling plant system network, chilled water temperature difference ,and the building application type from single one to a different buildings applications .The results of the research expose the energy consumption variations with the mentioned variables 1.1 INTRODUCTION U 1.1.1General U Egypt is one of the countries that face 3 major problems: -It has as an increasing electric demand which led the government to invest in (nuclear, renewable energies ) -Lack of energy saving culture. -Finally the private business investment sector focus only on the initial cost (cheapest initial price win the bid) with short period turnover profit. Those above major problems led to the following results in HVAC systems: Many office companies were selected on cheaper systems such as DX splits systems which consume high electric power Over exaggerated load calculation design which led over sizing equipment which led over size electric transformers from which consume higher electric power.Cairo and Nile shore cities (Menya ,Aswan, Luxor, etc) should not be designed on air cooled chilled water systems as it consumes higher electricity.Individual buildings with separate Chilled water systems or chiller plants costs a lot rather than one central plant as it will be discussed later in the advantages of district cooling systems. 1.2 ADVANTAGES OF DISTRICT COOLING? : 1- Increasing demand comfort cooling for construction of many new buildings that are tighter than older building and contain more heat generating equipment such as computers. 2- In the Last ten years a growing trend towards out- sourcing, certain operations to specialists companies that can provide these services more effectively. 3- Reduction in peak electricity demand provided by district cooling 4- Environmental policies to reduce emission of air pollution, green house gases and ozone depleting refrigerants. 5- The most important, the customer value provided by district cooling service in comparison with conventional approaches to building cooling. District Energy Analysis and economic analysis was studied for a model prototype existing in Cairo Egypt. Different scenarios on the district cooling chosen model will be discussed in the Discussion and results 1.3 DISTRICT COOLING SYSTEMS 1.3.1. Definition A district-cooling system (DCS) is a sustainable means of cooling energy distribution through mass production. The basic provisions are shown in Fig. 1.1 A cooling medium like chilled water is generated at a central refrigeration plant and supplied to a site area comprising multiple buildings, through a closed-loop piping network. From each connection point of the distribution mains, a controlled flow of the Coolant is delivered to the air-conditioning equipment of the user buildings to handle their space-cooling demands. Without the installation of chiller plants in individual buildings, users may utilize their building space more effectively. The DCS chiller plant is higher in efficiency than the conventional chiller plants at individual buildings. It is also flexible to incorporate a range of inter-related thermal technologies, i.e. low-temperature coolant production (such as ice slurry) , thermal storage (with water, ice or eutectic salt) , co-generation (with waste-heat boiler and absorption chiller) , and tri-generation (electricity, chilled water and hot water Figure 1.1 District cooling production Layout . ` 1.4 DISTRICT COOLING EFFICIENCIES IDEA Best Practice guide (2008), as shown in Figure 2.2 summarize representative peak electric demand efficiencies of several major types of district of cooling systems, and compares them with representative peak demand conventional air cooled system. SYTEM TYPE 2 1.87 1.8 1.6 1.4 1.2 0.9 1 0.75 0.8 0.49 0.6 0.4 0.25 0.2 0 AIR COOLED BUILDING DISTRICT DISTRICT SYSTEM COOLING(ELECTRIC) COOLING(ELECTRIC) DISTRICT COOLING (100% DISTRICT COOLING(50% GAS FIRED) GAS FIRED WITH TES WITH TES S YS TEM TYP E Figure 1.2 Different type of district cooling system efficiency District cooling reduce demand in new development by 50% to 87% depending on the type of district cooling technology used. A straight centrifugal will cut peak compared with the conventional air-cooled approach by about 50%.The impact of thermal energy storage (TES) depending on the peak day load profile of the aggregate customer base .The graph illustrates a representative situation in a mixed use development in the Middle East ,in which TES reduced the peak power demand of the district system by about 20%. Natural gas district cooling can provide more dramatic reductions in power demand of .engine-driven chillers are the most cost effective gas-driven approach .Figure 2.7 shows the peak power demand of two gas-driven options 100% gas-driven without TES and a Hybrid in which 50% of the Capacity is gas driven,40% is electric driven and 10% TES. 1.5 OPTIMIZING CHILLED WATER DESIGN TEMPERATURES: Design and Specification Guide Optimizing chilled water supply and return temperatures involves not only minimizing the life-cycle costs of the chiller plant itself but also the costs of the air handling systems that the chiller serves. This is because these temperatures will have an impact on the characteristics of the chilled water coil design, which in turn will affect the pressure drop capacity and the energy use of the supply air fan. Table 1.1 shows the typical range of chilled water temperature difference (commonly referred to as delta-T) and the general impact on energy usage and first costs. The table shows that there are significant benefits to increasing delta-T from a firstcosts and point, and there may be a savings in energy cost as well, depending on the relative size of the fan energy increase versus pump energy decrease as delta-T increases. Chiller energy usage is largely unaffected by delta-T for a given chilled water supply temperature; Cool Tools TM Chilled Water Plant, [2000] 1.5.1. Impact on First Costs and Energy Costs of Chilled Water Temperature difference: Fortunately, within the range of commonly used chilled water supply and return temperatures, the impact on the airside of the system is seldom significant. Table 1.2 shows a typical cooling coil’s performance over a range of chilled water delta-Ts. While the example in the table will not be true of all applications, it does suggest that airside pressure will not increase very much as chilled water delta-T rises, while waterside pressure drop falls significantly. For variable air volume systems, the impact is even less significant because any airside pressure increase will fall rapidly as airflow decreases. Table1.1, Impact of chiller water temperature on airside system, (COOL TOOLS, 2005) 1.6 SELECTING CHILLED WATER DISTRIBUTION SYSTEM FLOW ARRANGEMENT: The best choice for a given project can be selected without an unnecessarily burdensome analysis. Table 1.2 shows recommendations for distribution system options based on the size and number of loads served and distribution system losses. These recommendations are generalizations that should apply to the majority of typical HVAC applications, but they may not prove to be optimum for every application. Cool Tools TM Chilled Water Plant, [2000] retrieved July 23, 2001, from PsycINFO database. Table (1.2) Recommendations for distribution system options based on the size and number of loads served and distribution system losses, (COOL TOOLS, 2005) . Note that the suggested definition of “many” coils (more than 5) and “high” distribution losses (more than 40 feet pressure drop) are rules of thumb. When the actual system design is near these limits, both the few/many and low/high distribution system options should be analyzed to see which optimum .Application is Notes (correspond to application number at left of Table 1.3): 1. For a plant serving one coil, the system shown in Figure 1.3 is usually the most cost-effective approach. It eliminates the expense and pressure drop of a control valve and realizes significant energy savings from the wide range of chilled water temperature reset that occurs. 2. For plants serving groups of large loads such as buildings in a college campus, terminals in an airport, etc., distributed variable-speed-driven secondary pumps Figure 1.4 is usually the best solution. The use of distributed pumps reduces pump energy by allowing each secondary pump to be selected and operated at the head required to supply water from the plant to the building. With a conventional primary-secondary scheme (Figure 1.4a), the buildings closest to the pumps will have more pressure than needed; this pressure is throttled by the control valves, which wastes energy and can cause control problems. Other advantages over conventional primary-secondary systems include: improved balancing; much better energy performance when only a few buildings are on-line; And elimination of the need or desire for reverses return. 3. For plants serving large individual air handling systems, distributed variable speed-driven coil secondary pumps (Fig. 1.4) is usually the best solution. This design will be less expensive than a primary-secondary system and cost competitive with a primary-only systemFig2.4b It will be more efficient than both these options for two reasons. First, this design eliminates the pressure drop (and expense) of control valves, generally about a 10-foot reduction in head. Second, as with the campus system, each secondary pump may be selected and operated at the head required to supply water from the plant to the coil. With a conventional primary-secondary scheme (Figure 1.4), the coils closest to the pumps will have more pressure than needed; this pressure is throttled by the control valves, which wastes energy and can cause control problems. Other advantages include better, more responsive control. Disadvantages include the need to have a pump at each coil. For this design to be energy efficient, coils must be large due to the inherent inefficiency of small pumps. If there are both small and large coils, a hybrid system of both distributed coil pumps and conventional secondary pumps to serve small coils is possible. (See Figure 1.4 for an example hybrid plant.) 4. When there are few coils in a system and the distribution head is low, the simplicity and low cost of a constant volume primary-only distribution system (Figures 1.3 & 1.5) is usually optimum despite its higher pump energy costs compared to variable-flow systems. Aggressive use of chilled water reset often allows the plant to have efficient energy usage despite higher pumping costs (as with application 1). With multiple chillers, a quasi-variableflow system can be attained by staging the chillers on coil demand, provided all the loads tend to vary together (i.e., no coil requires full cooling while others are at part load). This is typical of many HVAC applications where, for instance, the coils all are in VAV systems serving the same occupancy type. If there are multiple chillers in the system and the loads do not vary up and down together, the systems in application 5 should be used. 5. When the system distribution pressure drop is high, the return on investment for variable-flow systems improves and the optimum system will generally be a Primary-only pumping system (Figures 1.6 and 1.7) or a primarysecondary pumping system (Figure 1. 4a). Also, see the application notes discussed under application number When there are many valves in the system, the construction cost savings and start-up cost savings (no balancing) of using two-way valves versus three-way valves will generally offset the added cost and complexity of the bypass valve and controls required for the primary-only pumping arrangements shown in Figures 1.6 and 1.7, or the added pump installation cost of primary-secondary pumping Figure 1.4. They will improve controllability and possibly reduce simultaneous heating and cooling at heating/cooling air handlers. If variable-speed drives are not used, the Primary / secondary configuration should not be used since it offers virtually no benefits and adds to first costs. Figure 1.3 Constant –Flow piping, Single chiller, Single coil ` Figure 1.4 Constant-Primary/Secondary variable flow piping, distributed piping Figure 1.4a Primary/Secondary variable flow piping, multiple coils Figure1.4b Primary only Variable flow multiple coils Figure 1.5 Constant flow piping, single chiller multiple coils ` Figure 1.6 Constant flow piping, multiple chillers, multiple coils Figure 1.7 primary only single chillers, multiple coils 2- Methodology of Software used to Build and study the Model U INTRODUCTION: During the last 50 years , the dynamic modeling equation has been developed with the development with the numerical analysis solutions for the partial differential equations as shown in figure 2.1, how the accuracy has been increased with the developed methods , ASHRAE transfer method has been chosen for the software used to simulated the model which is a very convenient way for the accuracy results, and simulation time, the definition and assumption of ASHRAE transfer method will be explained though how it handles solving the solar time ,transmission load internal load simulation modeling equations. Complexity Accuracy Figure 2 .1 different methods for cooling load and simulation . 2.1 PRINCIPLES OF THE TRANSFER FUNCTION LOAD METHOD: The Transfer Function Method is the culmination of work first published in 1967 by two scientists working for the Canadian National Research Council. The method is based on an idea known as the "Response Factor Principle". This principle states that for a specific room, the thermal response patterns (i.e., how a heat gain is converted to load over a period of time) for each specific type of heat gain will always be the same. That is, for a specific room, a 293 watt (1000 BTU/h) heat gain through an exterior wall will cause the same response over a period of hours as a 586 watt 2000 BTU/h heat gain, Kusuda (1969). The sizes of the loads will differ, but the heat gain to load conversion pattern will be the same. This topic explains the key principles used to calculate building loads with the Transfer Function Method. This method is used in the HAP software program for the selected model and for its energy simulation load calculations. The explanation of Transfer Function Method principles requires covering a series of topics, including ` discussion of: 1. Necessary considerations for analyzing heat transfer in buildings. 2. Principles of the Heat Balance Method, which is the most rigorous load method available. 3. Fundamental principles of the Transfer Function Method which evolved from the Heat Balance Method. 4. Fundamental procedures used to calculate Transfer Function loads. 5. Examples illustrating how loads are calculated using Transfer Function procedures. Each topic will be covered in a separate section below. A final section will summarize the discussions. 2.1.1 Fundamental Transfer Function Principles: The Transfer Function Method is the culmination of work first published in 1967 by two scientists working for the Canadian National Research Council. The method is based on an idea known as the "Response Factor Principle". This principle states that for a specific room, the thermal response patterns (i.e., how a heat gain is converted to load over a period of time) for each specific type of heat gain will always be the same. That is, for a specific room, a 1000 BTU/h heat gain through an exterior wall will cause the same response over a period of hours as a 2000 BTU/h heat gain. The sizes of the loads will differ, but the heat gain to load conversion pattern will be the same. The Response Factor Principle is in turn based on three additional principles: 1. The Principle of Superposition: The total room load is equal to the sum of loads calculated separately for each heat gain component. 2. The Principle of Linearity: The magnitude of the thermal response to a heat gain varies linearly with the size of the heat gain. 3. The Principle of Invariability: Two heat gains of equal size occurring at different times will produce the same thermal response in a room. Together, these principles allow the simplification of the Heat Balance Method analysis for a building: 1. The Principle of Superposition can be used to break the heat transfer problem into manageable units since it allows loads due to each identifiable heat gain component to be computed separately. For example, loads due to an exterior wall heat gain, and a lighting heat gain can be computed separately and then added together to determine the total room load. By contrast, the heat balance method requires all heat gains in a room to be considered simultaneously. 2. The Principle of Superposition also allows the effects of heat gains each hour to be considered separately. For example, a lighting heat gain this hour will cause loads in the current hour and a number of following hours. This is because a portion of the heat gain is thermal radiation which is absorbed by the walls, floor and furnishings of the room, and is then convected to room air over time. When lights are on for several hours, the load in any one hour is due to heat gain during the current hour and heat gains in a number of previous hours. With the Principle of Superposition, the pattern of loads due to each hourly heat gain can be computed separately and then added together to determine the total lighting load each hour. By contrast, the heat balance method requires the effects of heat gains for the current hour and previous hours to be considered simultaneously. 3. The Principles of Linearity and Invariability permit a vast reduction in the number of calculations needed. Because the pattern of loads resulting from each type of heat gain will be invariable, the pattern only needs to be determined one time via heat balance computations. Then, because the magnitude of each load is a linear function of the size of the heat gain, load patterns due to each hourly heat gain can be easily computed using simple algebraic equations. By contrast, the heat balance method requires solving a series of heat balance equations simultaneously each hour. 2.1.2 Fundamental Transfer Function Procedures: With the Transfer Function Method, a general mathematical relationship which defines load as a function of heat gain and time is determined for each heat gain component in a room. This relationship is then ` used to quickly calculate loads for each hour. The mathematical relationship is expressed in what is called a Room Transfer Function Equation which looks like this: In this equation: 1. Q represents a load. The subscripts refer to specific points in time. Subscript 0 is the current hour, 1 is the previous hour and 2 is two hours previous. 2. q represents a heat gain. The subscripts 0, 1 and 2 have the same meaning as for loads. , are transfer function coefficients. Values of these coefficients vary for each type of heat gain 3. , , , and room due to the different heat transfer processes involved in converting each kind of heat gain into a load. ASHRAE has published tables of these coefficients for different heat gain components, room types, and building weights. In words, the Room Transfer Function Equation says that the load for the current hour (Qo) is a function of the heat gain for the current and preceding two hours, plus the loads for the preceding two hours. Because loads for the preceding two hours are themselves dependent on a series of heat gains for prior hours, this hour's load is really dependent on the effects of heat gains from many preceding hours. To use the Room Transfer Function Equation, transfer function coefficients must first be obtained. Then for any type of heat gain, calculating loads is a two-step process: 1. Determine the heat gains for a series of hours. 2. Use the heat gains and transfer function coefficients together in the Room Transfer Function Equation to calculate the loads. 2.1.3. Heat Extraction Method Principles: The Transfer Function Method also provides procedures for calculating how HVAC equipment removes heat from rooms in the building. This is referred to as the equipment "heat extraction rate". The procedures discussed in the preceding sections calculate loads assuming room temperature is maintained at a fixed level. However, in actual practice room temperatures vary within the thermostat throttling range, between cooling and heating set points, and when set points are set-up or set-back during unoccupied periods. The float of room temperature has a significant influence on the cooling or heating provided by the equipment. These considerations are also essential when computing pull down and warm-up loads resulting from the change from unoccupied to occupied period thermostat set points. Heat extraction procedures are involved in the system analysis process as follows: 1. Zone loads are computed using the heat gain and room transfer function principles outlined in the preceding sections. These loads are calculated assuming the HVAC equipment operates 24 hours a day and maintains a fixed zone temperature. Results of this calculation are reported as zone sensible load components on program reports. Zone sensible loads are also used to determine zone and system supply airflow rates. 2. Operation of the air handling system is then simulated using the zone load data and heat extraction procedures to determine how the equipment and thermostats respond to loads and extract or add heat to the zones. The zone temperature varies within the thermostat throttling range during operation, or within the dead band between cooling and heating set points. These simulation procedures are ultimately used to determine the total system heat extraction and the resulting system coil loads. Heat extraction procedures make use of a simple model of thermostat and equipment control, and a "Space Air Transfer Function" to determine how the thermostat and equipment respond to room loads. This section describes the basic procedures used in this analysis. First of all, the heat extraction method uses the following simple linear model for the thermostat control: = Heat extraction for time t, BTU/h or W. = Intercept for linear control profile BTU/h or W. S = Slope of linear control profile, BTU/h-F or W/K. = Room temperature for time t, F or C. Figure 3.4 illustrates thermostat control and heat extraction behavior for a situation in which the cooling set point is 72 F, the heating set point is 70 F and a 4 F throttling range is used. Within the cooling set point throttling range (72 F to 76 F), the thermostat calls for cooling and the HVAC equipment heat extraction is a linear function of zone temperature. Above the upper end of the throttling range, the heat extraction rate is fixed at its maximum value. Within the heating set point throttling range (70 F to 66 F), the thermostat calls for heating and the HVAC equipment heat addition rate is a linear function of zone temperature. Below the lower end of the throttling range, heat addition is fixed at its maximum value. Between the thermostat set points (70 F to 72 F), the thermostat does not call for cooling or heating. However, if air is still being introduced into a zone, some amount of uncontrolled heat extraction or heat addition will be occurring. 3 .RESULTS AND DISCUSSION 3.1 INTRODUCTION Five different Scenarios were simulated on Hourly Simulation software program, the model which is selected shown in appendix A with the full input data , consist of eight office buildings from an actual design , each scenario will resemble an important variable in Selecting and optimizing the design of district cooling plant .The output cooling capacity and simulations of the model is 1800 TR as shown in Appendix B, with VAV systems design with all the details. 3.2 COMPARISON SCENARIO BETWEEN CENTRAL DISTRICT COOLING PLANT AND INDIVIDUAL CHILLER PLANTS FOR THE SELECTED MODEL: The first chosen scenario compares the total energy consumption of individual plants systems (chillers, pumps, cooling towers) of the selected model (8 office buildings) Vs a district cooling plant system ,Appendix C in the thesis shows the simulation energy reports for central District cooling plant scenario for the model including chillers , primary pumps, secondary pumps and cooling towers, also the simulation energy reports for water cooled individual plants scenario for each office building for the eight buildings. Graphs are drawn from the output simulations of HAP software as which shows each office building individually the Hourly consumptions, Figure 3.1 Shows the total Hourly consumption for the 8 office buildings Vs. the Central District cooling System consumption Which shows the choice of District cooling system has much lower consumptions, Figure 3.1 District cooling consumption vs. individual chiller plants hourly consumption graph 3.3 ENERGY SIMULATIONS BETWEEN DIFFERENT CONFIGURATIONS FOR DISTRICT COOLING PLANT ON THE SELECTED MODEL: 3.3.1 Simulation of two centrifugal chillers in series: The second chosen scenario comparing different plant chillers configuration to reach the optimum efficiency for the selected model following steps were done: 1- The selection of 2 centrifugal chillers in Series with their part load performance sheet. 2- The output data of HAP chillers sizing data were entered as an input data in The Chiller System optimizer Software compares energy and SPLV for different chiller configuration. 3-The Output Data of the model building profile from Appendix B were entered as input Data in The system chiller optimizer. 4-According to the bin weather data for Cairo and the building profile part load of the building as shown in Table(3.1) , the system part load value sheet is composed , forming the Bin weight factors and the system kw/ton 5-Figure (3.3), the graph illustrates the cooling ton hours with the building load% with the chiller system KW/ton Table( 3.1) custom part load value (PLV) sheet resulted from the BIN weather data for 2 centrifugal chillers 6-The highest Cooling ton hours at 60% of the building load with a consumption for the chillers systems 0.57 KW/ton as shown in Figure 3.2 Cooling Ton-hrs Chiller System kW/Ton 1250000 0.80 Cooling Ton-hrs Per Year 0.75 750000 0.70 500000 Chiller System kW/Ton 1000000 0.65 250000 0.60 0 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 Building Load (%) 70 80 90 100 Figure 3.2 Building load % profile vs. cooling ton and chiller system efficiency for 2 Centrifugal chillers in series 3.3.2Simulation of two absorption chillers in series The following steps were done: This scenario could not be established with lithium bromide as chilled water temperature cannot be lower than 40 F only with Ammonia Absorption chillers. 1- The selection of 2 absorption chillers in Series with their part load performance sheet, in were placed as input data in the CSO software. 2- The HAP output data of the building profile of the model were entered as an input data in The Chiller System optimizer Software program. 3-The Output Data of the model building profile as in Appendix B were entered as input Data in The system chiller optimizer. 4-According to the bin weather data for Cairo and the building profile part load of the building as shown in Table 3.2), the system part load value sheet is composed, Table 3.2 custom part load value(PLV)sheet resulted from the BIN weather data from 2 absorption chiller Cooling kWh Chiller System COP 1250000 1.550 1.525 1.500 1.475 750000 1.450 1.425 500000 1.400 Chiller System COP Cooling kWh Per Year 1000000 1.375 250000 1.350 1.325 0 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 Building Load (%) 70 80 90 100 Figure 3.3 Building load % profile Vs. cooling ton and chiller system efficiency for 2 Absorption in series 6-The highest Cooling ton hours at 60% of the building load with a consumption for the chillers systems COP 1.425 while 105000 ton hours will work below 30% of the chiller which is not reliable for Absorption 3. 3.3 Simulation of Combined (Centrifugal+ absorption chillers in series): In Appendix F the following steps were done: This scenario is very practical as the High frequency load would be handled the Absorption chiller and the low frequency load would be handled with the centrifugal chiller. 1- The selection of 2 absorption chillers in Series with their part load performance sheet, in actual. 2- The output data of point No 1 was entered as an input data in The Chiller System optimizer Software program. 3-The Output Data of the model building profile as shown in Appendix B were entered as input Data in The system chiller optimizer 4-According to the bin weather data for Cairo and the building profile part load of the building as shown in Table (3.3), the system part load value sheet is composed, forming the Bin weight factors and the system KW/Tons. 5-Figure (3.4), the graph illustrates the cooling ton hours with the building load% with the chiller system Chillers COP. 6-The highest Cooling ton hours at 60% of the building load with a consumption for the chillers systems COP 12 which is the best and the operation of both chiller is very reliable and efficient in all part loads. Table 3.3 custom part load value (PLV)sheet resulted from the BIN weather data from 2 Combined Chillers Cooling kWh Chiller System COP 1250000 12 11 10 9 750000 8 7 500000 6 Chiller System COP Cooling kWh Per Year 1000000 5 250000 4 3 0 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 Building Load (%) 70 80 90 100 Figure 3.4 Building load % profile Vs. cooling ton and chiller system efficiency for combines chillers (Absorption+ Centrifugal) in series 3.4 CHANGING THE MODEL FOR DIFFERENT APPLICATIONS: Comparing Design Data Schedules for the office building which was in the first scenario with the design schedules for the different applications which is the Second scenario: 1- In The simulation Hourly analysis program the selected model will be simulated on 8 office buildings with the same schedules of people, light and equipment. 2- A graph is drawn of the 8 office buildings load profiles as shown in figure 3.5. 3- A graph is drawn of the 8 different buildings load profiles (4 office buildings + school + Health care + Hotel + Mall) as shown in figure 3.6. 4- Comparing the total hourly analysis of the eight office buildings Vs, the 8 different applications ,it shows the reduction in the curve of the different applications which will lead to less consumption of energy as shown in figure 3.7. 5-Getting the output simulations of the 8 office buildings during monthly analysis ,and the output simulations of the different applications on monthly analysis basis and plotting both as shown in figure 3.8.Clear energy is shown saving when using different application in DCS systems. Figure 3.5 8 offices buildings tonnage hourly analysis Figure 3.6 8 different applications buildings tonnage hourly analysis Figure 3.7 Total SUM OF CONSUMPTION FOR 8 different applications buildings Tonnage hourly analysis vs. 8 OFFICE BUILDINGS Figure 3.8 Total SUM OF CONSUMPTION FOR 8 different applications buildings tonnage monthly analysis vs. 8 OFFICE BUILDING 3.5 EFFECT OF CHANGING THE CHILLED WATER TEMP. DIFFERENCE ACROSS DISTRICT COOLING PLANT ON THE SELECTED MODEL: Four different scenarios made on changing the chilled water temperature delta T across the cooler of the chiller which are 10F with leaving 44F, 10F with leaving 37.4F ,12F with leaving 37.4 F, 14F with leaving 37.4 F, and 16F with leaving 37.4 1- Selection and part load simulation of the 2 centrifugal chillers were made with delta chilled water temperature 10 F with leaving chilled water 44 F. 2- Selection and part load simulation of the 2 centrifugal chillers were made with delta chilled water temperature 10 F with leaving 37.4 F. 3- Selection and part load simulation of the 2 centrifugal chillers were made with delta chilled water temperature 12 F with leaving 37.4 F. 4- Selection and part load simulation of the 2 centrifugal chillers were made with delta chilled water temperature 14 F with leaving 37.4 F. 5- Selection and part load simulation of the 2 centrifugal chillers were made with delta chilled water temperature 16 F with leaving 37.4 F. 6- The result is shown below in figure (4.4) which shows the impact of higher delta T on lower flow rate (water gallon per minute) which affect the annual consumption of the secondary pumps of the model. 7- In district cooling a study must be made showing the impact of lower gallon per minute and Airside size versus the cost of over sizing the chillers for producing higher delta temp.(larger lift on the compressor). 8- As shown in the figure 3.9 lower leaving chilled water temperature affect the annual consumption as the sizing of the airside equipment with small coils with less gpm as shown the different between the 44f curve and the 37 F curve. Figure 3.9 Secondary pumps consumption for diff. delta chilled water temperature hourly analysis. 3.6 EFFECT OF TYPE OF NET WORK PIPING DISTRIBUTION OF THE SELECTED MODEL: I The detailed simulations of the primary secondary model and the variable primary model which as follows: 1- In the Simulation Hourly analysis program the plant distribution system will be selected on primary –Variable secondary with Delta chilled water 12 F. 2- Computing the power consumption results as shown in Table below for a peak day 31 of July for (chiller, primary pump, secondary pump, cooling tower). 3- In the Simulation Hourly analysis program the plant distribution system will be selected Variable primary with Delta chilled water 12 F. 4- Computing the power consumption results as shown in Table below for a peak day 31 of July for (chiller, primary pump, secondary pump, cooling tower). 5- From Table (3.4 ) and Table (3.5) A graph is plotted as shown in Figure ( 3.10 ) between the total hourly consumption between The primary Variable secondary pump distribution vs the variable primary distribution. 6-The Result from the graph shows the Variable primary total consumption is much better ,which a good point to study the pressure drop in Egypt as , most of its Land has a flat surface ,i.e. there is not much losses for the pipes ,and also if there is no high rise buildings ,then it should be studied carefully for primary secondary Table (3.4) HVAC equipment – cooling ton hours and electric consumptions for primary variable secondary distribution. Author A is a research fellow at Commercial Company, Cairo, Egypt, Author B is a professor in the Department of Mechanical Engineering, Cairo University, Cairo, Egypt. ` Table (3.5) HVAC equipment –cooling ton hours and electric consumptions for variable primary distribution. Figure 3.10 Hourly energy analysis between primary variable secondary Vs variable primary. CONCLUSIONS 1-District cooling system running cost has much lower energy consumption than Individual plant rooms. 2-Natural gas is a rich resource in Egypt which can used in direct fired absorptions chillers(in a combined plant systems with Centrifugal chiller as the high load would be handled by the absorption chiller the low fluctuating load would be handled by the centrifugal chillers. 3-Different application buildings would stretch the peak of the Chiller load with lower peak consumption. 4-Variable primary systems in Large district cooling systems with low rise building and less pressure drops would be feasible than primary-variable Secondary pumps. ACKNOLOWDGEMENT Thanks to all our colleagues at CAIRO University and CARRIER –Egypt for their technical support. REFERENCES ASHRAE HANDBOOK FUNDENTALS CHAPTER 19, "Climate design information”, The American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers, USA, 2009. ASHRAE HANDBOOK CHAPTER 14, " Energy Estimating and modeling methods”, The American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers, USA, 2009. ASHRAE Standard 62-2004: ventilation for acceptable indoor air quality ", American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air Conditioning Engineers, Atlanta, USA, 2004. ASHRAE, Procedure for Determining Heating and Cooling Loads for Computerizing Energy Calculations, Algorithms for Building Heat Transfer Subroutines”, American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air Conditioning Engineers, Inc., 1976. CARRIER, “Carrier System Design Manual, Part 1: Load Estimating”, Carrier Corporation, 1960. CARRIER” HAP Load Calculation Manual”. Carrier Software systems 2003-2010 Cool Tools TM., "A Cool Tools TM Chilled Water Plant Design and Specification Guide ", Cool Tools Report #CT-016 ,USA, 2000. IDEA, “Community - District Energy Systems: Preliminary Planning & Design Standards” National Energy Center for Sustainable Communities & International District Energy Association Safety and Health, NY, 2006. IDEA, " District Heating and Cooling in the United States: Prospects and Issues ", Committee on District Heating and Cooling, National Research Council, 1985. IDEA, " IDEA Report: The District Energy Industry:", International District Energy Association,USA,2005. U U Stephenson and Mitalas , “Response factors ASHRAE transfer function Dynamic model method Canada, 1969. View publication stats