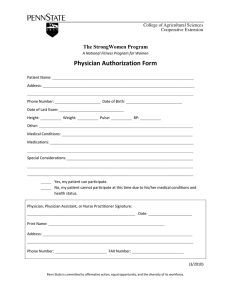

2009 QCCQ 5521 COURT OF QUEBEC Small Claims Division CANADA PROVINCE OF QUEBEC DISTRICT OF MONTREAL Civil Division No: 500-32-106186-077 DATE: June 9, 2009 ______________________________________________________________________ PRESIDED BY THE HONOURABLE DAVID L. CAMERON, J.C.Q. ______________________________________________________________________ DR. HENRY COOPERSMITH […] Westmount, Quebec […] Plaintiff vs. AIR CANADA 7373 Côte Vertu West St-Laurent, Quebec H4Y 1J2 Defendant ______________________________________________________________________ JUDGMENT ______________________________________________________________________ 2009 QCCQ 5521 (CanLII) Coopersmith c. Air Canada 500-32-106186-077 PAGE: 2 [1] When a physician travelling on an international flight assists another passenger in need of medical attention at the insistence of the person in charge of the cabin, is the physician entitled to a reward from the airline for this service? [2] Can a physician claim something for the loss or reduction of the benefit of the flight he otherwise would have enjoyed? [3] If the airline offers a token of its appreciation to the physician, should the value of what is offered be proportional either to the services given by the physician or to the benefit given up by the physician? [4] The Court has been asked to revolve a conflict between a physician and an airline arising in just such a case. The claim [5] Doctor Henry Coopersmith, a Montreal physician, seeks from Air Canada "fair and reasonable compensation from the Defendant for services he rendered at the insistence of Air Canada and for the benefit of Air Canada". In the detailed statement of claim, he particularises his claim as follows: i) For the costs expressed as the monetary equivalent of frequent flyer miles of a one way executive class fair plus applicable taxes: $1,350.00; ii) For the value of medical services rendered at an hourly rate: $ 708.00 iii) Compensation for the loss of one day of vacation: $1,000.00 TOTAL: $3,058.00 Air Canada's contestation [6] Air Canada raises a series of defences which the Court paraphrases as follows: 1. There is no cause of action because Dr. Coopersmith was acting pursuant to his ethical duties, which constitute a legal obligation; 2. The claim, sounding in damages, is excluded by the Montreal Convention; 3. Subsidiarily, the damages claimed are exaggerated and excluded under the Tariff implied by reference in the contract of carriage, which excludes consequential, special, punitive and exemplary damages; [7] In respect of the particular heads of the claim, Air Canada pleads: 2009 QCCQ 5521 (CanLII) INTRODUCTION 500-32-106186-077 Aeroplan points have no monetary value; ii) The claim for a professional fee constituted consequential damages because it does not constitute direct out-of-pocket expenses; iii) The claim for loss of enjoyment of a day's vacation constitutes consequential damages excluded under the Tariff. FACTS [8] Dr. Coopersmith, accompanied by his wife, was flying Air Canada in executive class seats on from Montreal to Paris on the evening of October 11, 2006. [9] Dr. Coopersmith responded to a request from the cabin personnel made over the public address system intended to obtain the collaboration of medical doctors to assist passengers apparently in need of medical attention. He took care of two passengers of whom only one required attention. A third passenger was attended to by another physician. [10] Dr. Coppersmith then returned to his seat to catch some sleep. He was awoken by the head flight attendant who insisted that he intervene in a situation where the other physician was preparing to give an injection of valium to the third passenger, stricken with a panic attack. [11] Because the head flight attendant had not been able to obtain proof of this other doctor's credentials and, convinced that Dr. Coopersmith was the appropriate person to treat the patient, she insisted that he become involved in the situation. [12] Dr. Coopersmith did not volunteer his assistance, believing that the passenger was being treated by another physician and that this physician had not asked for assistance. [13] The head flight attendant pleaded with the Plaintiff to deal with the situation. She was not comfortable with the other physician from whom she had been unable to obtain poof of his credentials. [14] The dispute with the other physician apparently arose because he was about to use the medical kit, which contained medication. [15] Air Canada provided an extract from its "Safety and emergency procedures cabin personnel", item "60. AIRCRAFT MEDICAL KIT". Under the heading "OPERATION" the text reads: If the Aircraft Medical Kit is required, Cabin Crew must: 1. Advise Captain or medical situation. 2009 QCCQ 5521 (CanLII) i) PAGE: 3 500-32-106186-077 2. PAGE: 4 Ask for valid identification to validate person's competence/training. [16] Dr. Coopersmith acquiesced reluctantly and, upon his arrival on the scene, the other physician, claiming to have previously identified himself to the flight attendants, became impatient, tossed the syringe into the Air Canada emergency kit and returned to his seat. [17] Dr. Coopersmith, using his skill and expertise, helped to relieve the patient from her anxiety without the use of medication. When she was sufficiently calm, after about one hour, he returned to his seat in executive class. He did not get any sleep because he was required to fill out various forms. At that point, Dr. Coopersmith expressed to the head flight attendant his expectation to receive something for his services. [18] In fact, Dr. Coopersmith worked during the flight, which was supposed to be part of a vacation, and arrived fatigued in Paris when he might have otherwise arrived rested. [19] Dr. Coopersmith was asked to fill in two flight medical incident reports, one for the first patient he attended to voluntarily (the other patient not requiring any assistance after verification) and the second for the third patient treated at the insistence of the chief flight attendant. The medical reports consist of two-page printed forms. [20] Dr. Coopersmith filled in the relevant information, ticking off the items as applicable and adding brief comments. [21] He was also asked to complete a document entitled "MEDICAL CARE PROVIDER INDEMNITY FORM PROTECTION CONTRE LES RÉCLAMATIONS EN DOMMAGES-INTÉRÊTS". The form reads as a contract to be signed by the captain on behalf of Air Canada and by the doctor who certifies that he is a duly qualified health professional. The fine print reads: AC hereby invites the HEALTH CARE PROFESSIONAL, and the HEALTH CARE PROFESSIONAL hereby volunteers, on the date hereunder, to provide emergency medical treatment to: The patient is identified and the fine print continues: In recognition thereof, AC declares that in so acting, the HEALTH CARE PROFESSIONAL will be protected and held harmless by AC from claims by the PATIENT or anyone claiming on his/her behalf alleging negligence in the performance of the services provided by the HEALTH CARE PROFESSIONAL. This indemnification shall not extend to damages caused by the gross negligence or wilful misconduct of the HEALTH CARE PROFESSIONAL. 2009 QCCQ 5521 (CanLII) […] 500-32-106186-077 PAGE: 5 Flight Attendant must complete this form when a physician, nurse, emergency medical technician or other qualified person performing medical services requests some form of indemnity before providing emergency medical service on board an Air Canada aircraft. [23] The rest of the fact pattern is constituted by an exchange of correspondence between Dr. Coopersmith and Air Canada. This exchange begins with a letter dated October 17, 2006 where Dr. Coopersmith writes to "customer solutions" recounting the facts that occurred on October 11, and requesting two executive-class tickets "as compensation for the work that I did", Dr. Coopersmith states his case as follows: As a result of my interventions, patient examinations, evaluations and follow-up as well as filling out the numerous forms required, I was not able to sleep and was required to work for a number of hours. This is not the first time that I have been requested to intervene on a flight but this is the first time I am requesting compensation. I did not think that it is adequate that the chief stewardess tells me how much she appreciated my help. I was kept busy for a number of hours and was unable to enjoy the flight with my wife. [24] The response, forwarded by Edward Bekeris, M.D., the Acting Senior Director, Occupational Health for Air Canada expresses "heartfelt thanks for your assistance during two medical incidents on one of our recent flights." [25] Dr. Bekeris analysis of the situation is as follows: The assistance and support you offered our crew, and the compassion you showed for both fellow travellers, were more than appreciated. While our crew members are trained in first aid, there are situations that call for an intervention that is beyond their capacities. Your spontaneous and expert assistance was of great help and comfort to all those aboard that day. To offset some of the convenience that you may have experienced, I am pleased to credit your Aeroplan account with either 10,000 status miles (towards Prestige, Elite or Super Elite status) or 15,000 miles (which once redeemed, is the equivalent of one free short-haul flight) … [26] Dr. Coopersmith responds October 25, 2006 restating his case as follows: I requested a replacement ticket of business class for my wife and myself in order to at least enjoy a similar type of flight for which I had paid and was expecting. Quite frankly one free short-haul is insulting and in no way reflects what I was required to do for Air Canada. 2009 QCCQ 5521 (CanLII) [22] The document is intended to be signed by the "health care professional" prior to providing medical services as is indicated by the preamble: 500-32-106186-077 PAGE: 6 [28] The escalation continues, this time with a letter from Dr. Bekeris dated November 7, 2006. Dr. Bekeris refers to the offer of points as a "token of our appreciation". When dealing with the ill passengers, the cabin crew staff might ask if there is a medical professional volunteer to assist the ill passengers. To this end, Air Canada offers a token in recognition of such act. Compensation is not offered as such changes the relationship from that of a Good Samaritan to that of a vendor providing a professional service. Services of a volunteer is the only request made by our In-flight staff. I would like to point out that the token, or gratuity, is intended as offered. It is intended to acknowledge volunteer medical assistance to an ill passenger. It does not contemplate professional fees or claims of service replacement. [29] The offer of Aeroplan points is reiterated. counsel appears as a "cc" to the letter. [30] that: At this point, Air Canada's legal On November 13, Dr. Coopersmith replies, restating his case, making the point I was charged 160,000 points as well as over $600.00 which represented various taxes and other fees for the privilege of flying executive class with my wife. I have requested that a similar amount of points be added as a token or gratuity as you put it for what you term "volunteer medical assistance to an ill passenger". [31] Referring to the cc to Air Canada's legal counsel, Dr. Coopersmith asks rhetorically: l would very much like to have her opinion as to whether when the head stewardess woke me up while I was sleeping, and begging me to come back to intervene in what she thought was a medical emergency constituted a "volunteer medical assistance" or whether another relationship developed. [32] Dr. Coopersmith reiterates his requests for reconsideration, for the name of the person to whom he can appeal the decision and intimates, for the first time, that legal remedies may be sought. [33] Receiving no reply, Dr. Coopersmith writes again on September 17, 2006 reiterating various points already raised in other letters. [34] On December 21st, Dr. Bekeris writes to state that he is awaiting a legal opinion from Air Canada's law branch. 2009 QCCQ 5521 (CanLII) [27] Dr. Coopersmith requests a reconsideration and, if is not forthcoming, to know to whom he can appeal the decision. [35] The next letter is from one of Air Canada's in-house counsel. quotes article 38 of the Code of ethic of physicians: PAGE: 7 The attorney A physician must come to the assistance of a patient and provide the best possible care when he has reason to believe that the patient presents with a condition that could entail serious consequences if immediate medical attention is not given. [36] She then reiterates the concept of the Good Samaritan. Nevertheless, as indicated by Dr. Bekeris, compensation is not offered as it would change the relationship from that of a Good Samaritan to that of a vendor providing a professional service. [37] The balance of the correspondence leads to a formal letter of demand enclosing a draft statement of claim. QUESTIONS IN ISSUE [38] The claim of Dr. Coopersmith is expressed as the joinder of two claims. One is a claim for remuneration for services rendered; the other is a claim for compensation for prejudice for having been put in the position where he was pressured into providing services where he had not volunteered to do so. [39] The defences raised by Air Canada in its correspondence and in its more detailed written contestation seek first to equate the doctor's medical ethical duty with the role of a Good Samaritan and to qualify the services as being compelled by a legal obligation, negating of any cause of action. [40] Subsidiarily, even if a legal claim should exist, Air Canada asserts the limitations imposed by the Montreal Convention1 because this is clearly an international flight between two signatory countries to which that convention applies. [41] Air Canada makes a further subsidiary argument that the damages are "consequential". Air Canada takes the position that both its Tariff and the Montreal Convention exclude damages which, although expressed as compensatory, should be deemed excluded under the Montreal Convention because they are "other than compensatory" or, to use an expression found in the jurisprudence concerning claims under article 17 of the Montreal Convention, claims that are for "purely psychologically" damages. [42] The Court gleans from the joinder of issue and the parties' arguments the following issues: 1 Carriage by Air Act ( R.S., 1985, c. C-26 ), SCHEDULE VI, CONVENTION FOR THE UNIFICATION OF CERTAIN RULES FOR INTERNATIONAL CARRIAGE BY AIR. 2009 QCCQ 5521 (CanLII) 500-32-106186-077 500-32-106186-077 1. PAGE: 8 In the circumstances of this case, does the Plaintiff have a claim: b) for reparation of prejudice based either in contract or an extra contractual obligation? 2. If the claim is found to exist, what is its proper quantification? 3. Is such a claim limited or excluded under the provisions of the Montreal Convention? Nature of the legal relationship between Air Canada and Dr. Coopersmith [43] On one level, Dr. Coopersmith was a passenger on an Air Canada flight with legal relationships flowing from the contract of carriage and international conventions. [44] In the context of dealing with the situation Air Canada had on its hands, the legal relationship is more difficult to define. With the patient, Dr. Coopersmith initiated a professional relationship governed by, as well as the general law, his code of ethics and the professional standards associated with membership in a professional corporation. It is not necessary to determine whether any fee could be required for his services from the patient since the patient is not a party to these proceedings. [45] In respect of Dr. Coopersmith's relationship with Air Canada, it is not possible to define this relationship as contractual: there was no express or implied stipulation of an obligation on the part of Air Canada to pay a fee for the services rendered to Air Canada and to its passenger. It was only after the services had been provided that Air Canada asked Dr. Coopersmith to sign a contractual form and learned that he would be seeking compensation. The form was never presented to the captain for signature. Dr. Coopersmith had not requested "some form of indemnity" indemnity" before providing services. A contract was not formed ex post facto. [46] Dr. Coopersmith was asked, in a very compelling way, to assist Air Canada in the resolution of a crisis that had came about because of an error of communication. [47] Air Canada was faced with an ill patient. Its chief representative in the cabin was not comfortable with the manner in which the patient was being attended to nor was she sure of the physician's identity. [48] The perception of Air Canada's chief flight attendant was that Air Canada could suffer prejudice, both in terms of the situation of the ill passenger, and that of other passengers who could be affected by her panic. 2009 QCCQ 5521 (CanLII) a) for remuneration; 500-32-106186-077 PAGE: 9 [50] Objectively, however, Air Canada could have avoided the problem by having better communications between the head flight attendant and the other flight attendants. The belief that the attending physician had not properly identified himself was probably erroneous. [51] If Air Canada had not intervened in the work of this other physician, things would have probably progressed to the point where the patient received a shot of valium and became calm. [52] The intervention of the head flight attendant in the work of that physician was probably inappropriate. [53] Rightly or wrongly, by intervening in that situation, Air Canada required a "plan B". This was provided by Dr. Coopersmith who, although reluctantly, did agree to go to the scene. [54] His participation in the events started as being part of Air Canada's problem (leading to the crisis where the attending physician threw down the syringe refusing to proceed further) to becoming part of Air Canada's solution (establishing a doctor-patient relationship in a way that was beneficial to Air Canada's management of its crisis). [55] While no contract existed between Dr. Coopersmith and Air Canada, a situation akin to a contract was generated. [56] The Civil code defines management of the business of another as follows: 1482. Management of the business of another exists where a person, the manager, spontaneously and under no obligation to act, voluntarily and opportunely undertakes to manage the business of another, the principal, without his knowledge, or with his knowledge if he was unable to appoint a mandatary or otherwise provide for it. [57] Air Canada takes the position that Dr. Coopersmith was under an obligation to act because of his ethical duties and further defines the situation of that of a "Good Samaritan". [58] In the Court's view, Dr. Coopersmith was not under a legal and ethical obligation to act. He was correct in assuming that another physician was in the process of treating the patient and that the other physician had not requested his assistance. 2009 QCCQ 5521 (CanLII) [49] Air Canada's chief flight attendant, from her subjective point of view, did the right thing by calling upon Dr. Coopersmith, who had already demonstrated his abilities in the earlier situation. 500-32-106186-077 PAGE: 10 38. A physician must come to the assistance of a patient and provide the best possible care when he has reason to believe that the patient presents with a condition that could entail serious consequences if immediate medical attention is not given. [60] It is far from certain that a panic attack is a condition that requires immediate medical intervention to prevent serious consequences. [61] Dr. Coopersmith raised the matter with the Canadian Medical Protection Association (the "CMPA"), an institution that provides legal assistance to physicians in a way that is analogous with professional liability insurance. The CMPA wrote: When called upon by aircraft staff to assist with the passenger, a physician should respond to the call, determine whether the situation is serious enough to require immediate assistance, and then decide whether to assist. If the situation does not require immediate assistance, then likely there would be no duty to assist and the exception at paragraph 9 of the Information Sheet would not apply. [62] In other words, the physician would find himself without protection from the CMPA in a case where he intervened in a circumstance where the situation did not require immediate medical assistance. [63] Therefore, the Court concludes that Dr. Coopersmith was not acting out of a legal obligation. Interestingly, the doctrine2 takes the view that the notion of obligation to act in article 1482 has a fairly narrow scope, applying in cases of a "specific" obligation. Pour qu'il y ait gestion d'affaires, il faut aussi que le gérant ne soit pas spécifiquement obligé par la loi ou par jugement de s'occuper des affaires du géré. Le tuteur, le curateur, le syndic à la faillite, le liquidateur, l'administrateur des biens d'autrui, en général, ne peuvent donc être gérants des affaires des biens qui leur ont été confiés dans l'exécution de leurs fonctions. En revanche le devoir général d'agir en personne prudente et diligente (article 1457 du Code civil) ne fait pas obstacle à la gestion d'affaires. Il devrait en être ainsi même pour son application particulière au bon samaritain, qui prête secours à une personne dont la vie est en péril, pour les dépenses effectuées ou le préjudice (blessures, etc.) qu'il subit lui-même. [64] The authors of that text make reference to article 2 of the Charter of human rights and freedoms, R.S.Q. c.C-12 and article 1471 C.C.Q. 2 Beaudoin et Jobin, Les obligations, 6e édition, Cowansville, Les Éditions Yvon Blais Inc., 2005, para. 541 2009 QCCQ 5521 (CanLII) [59] Furthermore, it is not entirely clear that the situation of the particular patient constituted a situation giving rise to the application of section 38 of the Code of ethics of physician: 500-32-106186-077 PAGE: 11 [66] The Court, therefore, comes to the conclusion that Air Canada is bound under an obligation flowing from the management of the business of another (gestion d'affaires) qualified by the authors Pineau, Burman, Gaudet3, as "Une source autonome d'obligation." Quantification of the claim [67] The recourse of the "manager" is defined in article 1486 C.C.Q. as follows: 1486. When the conditions of management of the business of another are fulfilled, even if the desired result has not been attained, the principal shall reimburse the manager for all the necessary or useful expenses he has incurred and indemnify him for any injury he has suffered by reason of his management and not through his own fault. The principal shall also fulfil any necessary or useful obligations that the manager has contracted with third persons in his name or for his benefit. [68] The notion of reimbursement of expenses has been applied in jurisprudence to include the price of the services of the manager himself. For example, in Garage Deschênes Inc. c. Transport Baie-Comeau Inc.4 a towing company was awarded an amount for towing a wrecked tractor-trailer from the site of a highway accident at the request of the police. These were not costs payable to a third party, they were the fair fees evaluated by the Court for the services provided by the manager. [69] By analogy, the Court can determine a fair fee for the intervention of Dr. Coopersmith. This is not necessarily the fee he would charge for the specialized work of a medical-legal expert report, nor would it be determined by the fees charged to the RAMQ for a routine consultation conducted in the doctor's office. The Court arbitrates the amount at $500. [70] To award the full value of a return flight in business class would be exaggerated. The basic benefit of the flight was not lost. [71] As for the inconvenience, loss of enjoyment of the flight and the holiday, whether it is conceptualised as a clam for damages or for reimbursement of a portion of the price of the ticket, the Court finds that $500 should be sufficient to compensate Dr. Coopersmith for the prejudice. 3 4 Pineau Burman Gaudet, Théorie des obligations, 4e édition, Les Éditions Thémis Inc., 2001. para. 262 (C.A.) AZ-50168227 - The question in the Court of Appeal was whether the towing company had a right of retention. 2009 QCCQ 5521 (CanLII) [65] Even if it were found that the physician had a duty to act, the provisions of article 1482 would still apply. PAGE: 12 [72] Air Canada made much of the concept that Aeroplan points cannot be equated with a monetary equivalent. Despite a stipulation to that effect in Aeroplan's literature, it cannot be denied that the thing one receives in return for aeroplan points, a plane ticket, does have an economic value to the recipient, although it cannot be traded or sold, there being no market. [73] By offering, ex gracia, a quantity of points as a token, Air Canada opened the debate. I might have been wiser for Air Canada to offer a more substantial token. But, the Court cannot blame a litigant for remaining firm in its negotiation and submitting the matter to the Court for its opinion. Application of the Montreal Convention [74] It is not in issue that Dr. Coopersmith was on an international flight as defined in the Montreal Convention. [75] The question in issue is whether that context precludes all recourses, because of the provisions of the Montreal Convention. It is useful to cite certain parts of the Montreal Convention: ARTICLE 1 — SCOPE OF APPLICATION 1. This Convention applies to all international carriage of persons, baggage or cargo performed by aircraft for reward. It applies equally to gratuitous carriage by aircraft performed by an air transport undertaking. ARTICLE 29 — BASIS OF CLAIMS In the carriage of passengers, baggage and cargo, any action for damages, however founded, whether under this Convention or in contract or in tort or otherwise, can only be brought subject to the conditions and such limits of liability as are set out in this Convention without prejudice to the question as to who are the persons who have the right to bring suit and what are their respective rights. In any such action, punitive, exemplary or any other non-compensatory damages shall not be recoverable. [76] Recourses are limited to claims respecting accidents, losses or damage to merchandise and delays5. [77] If the Montreal Convention applies, the claim, to the extent that it is an action in damages, is excluded, because it does not fall under one of the cases of liability of the carrier. [78] The claim for "necessary and useful expenses" is not a claim for damages. It is, therefore, not subject to the restrictions of the Montreal Convention6. 5 Articles 17, 18 and 19. 2009 QCCQ 5521 (CanLII) 500-32-106186-077 500-32-106186-077 PAGE: 13 [80] Air Canada does assert that a contract was formed, under the terms of which it agreed to hold Dr. Coopersmith harmless from claims by the patient. By asserting the existence of this contract, and its enforceability, it is difficult for Air Canada, logically, to affirm that the Montreal Convention would preclude contractual recourse, for example, an action in warranty by Dr. Coopersmith for indemnification in case of a claim by the patient. [81] The situation that the Court has defined as management of the business of another does not flow from "the carriage of passengers, baggage and cargo". [82] The fact that it occurred during the flight does not signify that it is an action in respect of the carriage of passengers, baggage and cargo. The flight is the occasion on which the facts occurred, but the claim does not arise out of the contractual and extra contractual obligations of Air Canada pursuant to the international carriage. The situation is no different than it would have been if Dr. Coopersmith had been called upon to act prior to boarding in the waiting room area assigned to Air Canada. [83] Given this finding, it is not necessary to discuss Air Canada's pretension that the Montreal Convention and the Tariff exclude the type of damages Dr. Coopersmith is claiming. CONCLUSION [84] In the very unusual circumstances of this case, the Plaintiff is entitled to claim expenses and damages resulting from his management of the business of another - the resolution of a crisis resulting from a mis-communication on the part of Air Canada's staff during a medical situation – notwithstanding the limiting provisions of the Montreal Convention. 6 This Court found in Lubov c. Air Canada Inc. (2008 ACCQ 9100, Gilles Lareau, J.C.Q.) that an action in quanti minoris for fraud ("dol") was not a claim in damages of the type excluded by the Montreal Convention. 2009 QCCQ 5521 (CanLII) [79] As for the aspect of the case that is a claim in damages, the fact that the legal situation developed during an international flight is merely incidental, as it would have been if Air Canada had entered into a contract with Dr. Coopersmith during the flight. 500-32-106186-077 PAGE: 14 CONDEMNS the Defendant to pay the Plaintiff the sum of $1,000, together with interest at the legal rate of 5% per annum and the additional indemnity provided at article 1619 of the Civil Code of Quebec, calculated from November 13, 2006; CONDEMNS the Defendant to pay, to the Plaintiff, judicial costs in the amount of $123. __________________________________ DAVID L. CAMERON, J.C.Q. Dates of hearing: November 24, 2008 and February 10, 2009. 2009 QCCQ 5521 (CanLII) FOR THESE REASONS, THE COURT: