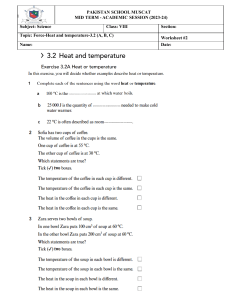

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/315829435 Revised Stratigraphy and Mineral Resources of Kirthar Basin, Pakistan Technical Report · January 2017 CITATIONS READS 9 1,475 4 authors, including: M. Sadiq Malkani Geological Survey of Pakistan Zafar Mahmood Malik 28 PUBLICATIONS 258 CITATIONS 250 PUBLICATIONS 4,879 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE All content following this page was uploaded by M. Sadiq Malkani on 25 February 2018. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. Government of Pakistan Ministry of Petroleum & Natural Resource Geological Survey of Pakistan Information Release No. 1010 Revised Stratigraphy and Mineral Resources of Kirthar Basin, Pakistan By M. Sadiq Malkani Zafar Mahmood Nasir Somro Sohaib Iqbal Shaikh Issued by Director General, Geological Survey of Pakistan 2017 CONTENTS Page Executive Summary 01 Introduction 02 Materials and Methods 03 Results and Discussion 03 Revised Stratigraphy of Kirthar Basin (Lower Indus Basin), Pakistan 03 Revised Stratigraphy of Western Kirthar Basin (Kirthar Range and 03 Surroundings), Balochistan Province Revised Stratigraphy of Eastern Kirthar Basin (Laki Range and Surroundings) 18 Basin, Sindh Province 23 Stratigraphy of Indus Offshore (Gondwana Fragment) Rocks of Nager Parker Igneous Complex (A Geo-Heritage of Indo-Pak Shield) 23 Stratigraphic Correlation of Kirthar Basin (part of Gondwana) with adjoining Balochistan Basin (part of Tethys), Pakistan Correlation of Revised Stratigraphic Set Up (At Group and Formation Level) of Lower, Middle and Upper Indus basins Mineral Resources of Kirthar Basin (Lower Indus Basin), Pakistan 24 Mineral Resources of Western Indus Suture (WIS; Suture between Indus and Balochistan Basins), Balochistan Province Mineral Resources of Western Kirthar Basin (Kirthar Range and surroundings), Balochistan Province Mineral Resources of Eastern Kirthar Basin (Laki Range and surroundings), Sindh Province Mineral Resources of Indus Offshore 27 Mineral Resources of Nagar Parker (A Remnant of Indo-Pak Shield), Sindh Province Installation of Museums, Global and National Geoparks-An Innovation for Sustainable Development of Provinces and Pakistan References 40 ii 25 27 27 31 39 40 42 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Kirthar Basin is subdivided into western Kirthar (Kirthar range and westward upto western Indus Suture) under Balochistan Province while eastern Kirthar (Laki range and eastward up to Nagar Parker Igneous Complex of Indo-Pak shield). Western Indus suture is a suture between the Indus basin (part of Indo-Pak subcontinental plate) and Balochistan basin (a heritage of Tethys). Western Indus Suture consists of ophiolitic, igneous and associated sedimentary and metamorphic rocks. So ophiolite related minerals like chromite, asbestos, magnesite, manganese, iron, barite, fluorite, etc are found. The western Kirthar Basin under the territory of Balochistan Province consists of exposed Mesozoic and Cenozoic sedimentary rocks. This area includes mineral commodities like coal, iron, fluorite, sulphur, building stones, decorative stones, marble, celestite, etc. The eastern Kirthar Basin under the territory of Sindh Province consists of exposed Late Cretaceous and whole Cenozoic sedimentary rocks. This area hosts coal, iron, laterite, ochre, celestite, placer tungston/sheelite, gold and other heavy mineral concentrates (magnetite, ilmenite, garnet, epidote, zircon, tourmaline, amphibole/hornblende and tremolite, apatite, pyroxene, etc), alum from pyritiferous shales, trona (source of Na), potash slats associated with rock salt deposits and lakes, gypsum, china clay, fuller’s earth, fire clay, cement industry raw materials, disseminated pyrite in carbonaceous shale and coal; abrasives type red ochre, coal, grity Pab sandstone, silica sands, radioactive mineral/uranium resources, construction stone, gemstone like agate and chalcedony, chert, flint and jasper from placer deposits. The Kirthar basin has vast natural resources like solar, air/wind, terrestrial water, marine water/ocean, tides, waves, current, land, biomass, etc. It is our urgent need to convert the non conventional energy resources into conventional energy resources. Kirthar land is receiving huge amount of energy from sun. The coastal areas have high potential of wind energy. Gravitational force of moon produces tidal energy in sea which can be converted in energy by the construction of dams which can store water at high tides and release water at low tides. Kirthar basin has a long sea shore from Nagar Parker to west of Karachi. Energy from sea waves can also be benefited by stable and non stable plate’s movements. Sindh also has a large waste biomass. The Nagar Parker Igneous complex consists of varicoloured igneous granite, other acidic and basic, and with some metamorphic rocks. This area host the significant construction/dimension stone resources like varicoloured granite and other basic and igneous rocks, gold and radioactive minerals like uranium, thorium etc can be explored), china clay, orthoclase feldspar and jewelry and gemstones like agate, chert, chalcedony, etc. 1 INTRODUCTION At the time of independence in August 1947, Pakistan was generally perceived to be a country of low mineral potential, despite the knowledge regarding occurrences of large deposits of salt, gypsum, limestone, marble, etc. During 1950-1980, the geological community of Pakistan can be credited with several major achievements in economic geology such as discovery of major gas fields in Balochistan, uranium from foothills of Sulaiman Range in Punjab and southern Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP), barite from Balochistan and KP, chromite and China clay in KP, famous emerald in KP, copper-gold and lead-zinc in Balochistan and KP. What has been found so far is much too small than what is expected to be discovered in not too distant future (Jan and Gauhar 2013). From independence to so far many economic geologists presented revised and updated data and papers on mineral deposits of Pakistan. From the beginning of Pakistan, many geoscientists incorporated the new discoveries in the previous records and reported the review of mineral/minerals of Pakistan or part of it. Gee (1949) presented a summary of known minerals of northwestern India (now Pakistan) with suggestions for development and use. Heron (1950) and Heron and Crookshank (1954) reported economic minerals of Pakistan. Ahmad (1969), Ahmad and Siddiqui (1992), Kazmi and Abbas (2001), recently Malkani and Mahmood (2016a;2017a) and Malkani et al. (2016) presented a comprehensive report on mineral resources of Pakistan. Malkani (2010a, 2011a) presented the mineral potential of Sulaiman foldbelt and Balochistan provinces respectively. Recently many discoveries of fluorite (Malkani 2002,2004b,2012b,2015a; Malkani and Mahmood 2016d,g; Malkani et al. 2007,2016), gypsum (Malkani 2000,2010a,2011a,2013a), celestite (Malkani 2012c,2015a; Malkani and Mahmood 2016d; Malkani et al. 2016), coal (Malkani 2004c,2012a,2013b,2016a; Malkani and Mahmood 2016c,f; Malkani and Shah 2014,2016), construction materials (Malkani 2016b), clay and ceramic (Malkani and Mahmood 2016e), goldsilver associated with antimony (Malkani 2004a,c, 2011a), cement resources (Malkani 2010a,2011a,2013a), marble (Malkani 2004a,2010a,2011a), barite (Malkani and Tariq 2000,2004), gemstones (Khan and Kausar 1996,2004,2010a), K-T boundary minerals (Malkani 2010b), copper, REE, etc are made. Further recently the abstracts on minerals of provinces (except Balochistan detail report by Malkani 2011a), like Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (Malkani 2012d,2013a,b; Malkani et al. 2013; Malkani and Mahmood 2016g), Sindh (Malkani 2014a), Punjab (Malkani 2012e), Gilgit-Baltistan and Azad Kashmir (Malkani 2012d,2014b; Malkani and Mahmood 2016g), and areas like Sulaiman (Malkani 2004a), Siahan-Makran (Malkani 2004a,d), etc are presented but detailed reports are lacking. Ahmad (1975) and Malkani (2011a) reported the mineral resources of Balochistan Province but other provinces were ignored continuously. Recently Malkani et al. (2017a) reported mineral resources of and basins (Malkani et al. 2017a,b,c,d,e,f,g,h,i) and Kirthar basin here. Akhtar et al. (2012) prepared the Geological map of Sindh province (including only eastern Kirthar and Nagar Parker) with some description of stratigraphic units. Here the revised staratigraphy and mineral resources of western and eastern Kirthar basins are presented in brief. Previously the Kirthar basin was ignored and also received little attention but the present authors filled the missing link. This report is handy, comprehensive reviewed, easy access and easy to read for the researcher, mine owners and planners. This report will add insights on revised stratigraphy and mineral resources of western and eastern Kirthar basin. 2 MATERIALS AND METHODS The materials belong to compiled data from previous work and also new field data collected by Malkani (the principal author) during many field seasons and vast field work in Kirthar basin and also adjoining other basins of Pakistan (Fig.1,2) about revised stratigraphy, paleontology, mineral commodities, lithology, structure, geological history, paleobiogeography, geodynamics/tectonics, etc. The methods applied here are many discipline of purely geological description. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION REVISED STRATIGRAPHY OF KIRTHAR BASIN (LOWER INDUS BASIN), PAKISTAN Kirthar basin shows mostly the same lithological units like Sulaiman basin during Mesozoic and Quaternary but vary in Tertiary strata. Further the Tertiary strata of western Kirthar basin (QuettaMastung-Kalat-Khuzdar and Lasbela areas of Balochistan) are also slightly different than eastern Kirtan basin (all areas of Sindh province). REVISED STRATIGRAPHY OF WESTERN KIRTHAR BASIN (KIRTHAR RANGE AND SURROUNDINGS), BALOCHISTAN PROVINCE Western Kirthar basin as name shows it is located in the western part of Kirthar basin occupied by Kirthar range and surrounding areas. On the west it is bounded by southern part (Khuzdar-Lasbela) of Western Indus Suture belt and then Makran range of Balochistan basin, on the east by eastern Kirthar basin, on the south by Indo-Pak Ocean and on the north by Sulaiman basin. Western Kirthar basin represents exposed Mesozoic and Cenozoic rocks, however in subsurface the Paleozoic and Precambrian rocks may be found. The exposed stratigraphic sequences in the western Kirthar basin under the Balochistan Province are being described as follows. Triassic Khanozai Group It is named by Fatmi et al. (1986) for Gwal and Wulgai formations exposed in the Western Indus Suture (Shirinab area of Mastung and Kalat, Gwal-Khanozai, Zhob) and at the contact of Sulaiman with Balochistan basins. Gwal Formation Gwal named by Anwar et al. (1991) after Gwal village. It consists of variegated shale and thin bedded limestone and marl with rare mafic intrusion and diabase flow. On the basis of ammonites including Meekoceras, Owenites, Anakashmirites, Anasibirites, Durgaites, Hemiprionites, etc the age is Early Triassic (Late-Middle Scythian). It is exposed in Khanozai, Zhob, Quetta, Shirinab (Mastung, Kalat), etc, areas. It is 350 m thick in the Trakai-Gwal section. It contains exotic blocks of Permian limestone containing brachiopods, corals etc. Its lower contact is not exposed and upper contact with Wulgai is sharp and conforable with fossiliferous conglomeratic and dense limestone. Wulgai Formation 3 Wulgai is named by Williams 1959 after Wulgai village for variegated shale with medium bedded limestone of Middle to Late Triassic age exposed in the Western Indus Suture regions like Shirinab area of Mastung and Kalat, Khanozai, Zhob, etc. It is 180 m thick in the Trakai-Gwal section. Its lower contact with Gwal is sharp with fossiliferous conglomeratic and dense limestone and upper contact with Spingwar formation seems to be conformable. The fossils like radiolarian, conodonts and some Spiriferinid brachiopods in basal limestone indicates Middle Triassic age and Holobia, Daonella (Bivalves) and ammonites like Cladescites, Jovites, Arietoceltites, Anatomites, Juvavites, Arcetes indicating Late Triassic. Jurassic Sulaiman Group The term “Sulaiman limestone” was first used by Pinfold (1939), the type section in the gorge between Mughal Kot and Dhana Sar (lat. 310 26’N; long. 700 01’E) was formally described by Williams (1959), and later “Sulaiman Limestone Group” is used by the Geological Survey of Pakistan. The Alozai group was used by Shah (2009) for Spingwar and Loralai formations only on the suggestions of A.N Fatmi that the Alozai group is well exposed in the Quetta to Zhob. Malkani (2009a) used the term Sulaiman Group for the Spingwar, Loralai/Anjira, Chiltan/Takatu/Zidi and Dilband formations. Mesozoic rocks are mostly pericratonic marine shelf sloping westward from Indo-Pak Peninsula. The sequence show igneous rocks in and near vicinity of western Indus suture. Spingwar Formation The Spingwar member of Shirinab Formation was named by Williams (1959) and he designated the type section at Spingwar at the north of Zamari Tangi, about 35 km northwest of Loralai (lat. 300 32’ 52’’N; long. 680 19’ 16’’E). Stratigraphic committee (Shah, 2009) upgraded it to the formation level due to wide and thick exposures and clear cut differences among the under and overlying strata. It consists of grey to greenish grey shale, grey to whitish grey marl and limestone with some igneous sills especially in the vicinity of Western Indus suture (Axial Belt). It is mostly exposed near the western Indus suture. It is 665m in Zamari Tangi, 215m in the Mara Tangi, and 140m in the Tazi Kach sections (Fatmi 1977; Shah 2009). It is conformably contacted on the base with Triassic Wulgai Formation and upper contact with Anjira/Loralai Limestone. Its Upper Triassic to Early Jurassic age is based on fossils of ammonites, brachiopods, bivalves, crinoids, corals and shell fragments (Williams, 1959; Anwar, et al, 1991; Fatmi 1977). Anjira Formation The Anjira member of Shirinab Formation was named by Williams (1959) after Anjira village (34L/7) with type locality 12 km east of Anjira (Anwar et al. 1991). It is correlative to Loralai limestone of Sulaiman basin. It represents mainly thin to medium bedded grey limestone with some grey shale and marl. Its lower contact with Spingwar Formation and upper contact with Chiltan (Takatu, Zidi) Limestone is conformable. The age assigned by Williams (1959) and Woodward (1959) is Early Jurassic but HSC (1961) have recorded Torcian fossils from its lower part. Its age ranges from Late Liassic to Bajocian (Early-Middle Jurassic). Chiltan (Takatu/Zidi Limestone) Formation The famous name Chiltan limestone was introduced by Hunting Survey Corporation (1961) after the Chiltan Range southwest of Quetta. The type locality of Chiltan is after the Chiltan Range (Lat. 30 0 4 01’ N; Long. 660 46’E). Shah (2002,2009) named the Takatu Formation after the Williams (1959). Its name was derived from the Takatu Range in the Northeast of Quetta. The type section is along Data Manda Nala, a small stream passing throughout the entire formation in very deep narrow gorge and enters the plain about 3km south of Bostan village (Lat. 300 20’N; Long. 670 03’E). The term Chiltan Limestone is well known in all geoscientists. It is also valid in most of the Kirthar, Sulaiman and Axial belt areas. It consists of massive thick bedded limestone which forms prominent ranges and high peaks in the surrounding of Quetta, Ziarat and then in the Takht Sulaiman area, however in the vicinity of Loralai, the peak forming equilent is Loralai formation. This limestone is considered as biohermal or reefal. This formation is 800m thick in the type locality and 1100m in the Takht Sulaiman and in other areas varies from 600 to 1100m (Fatmi 1977; Shah 2009). The lower contact of Chiltan (Takatu) Limestone with Anjira/Loralai Formation is conformable while upper contact with Dilband/Sembar Formation is disconfirmable and at places conformable. Arkell (1956) reported Late Bathonian ammonites from the lower part of Mazar Drik unit/Dilband Formation, its age can be considered as Early Callovian to Late Bathonian (Middle Jurassic) (Fatmi 1977). Its stratigraphic position also tells the age range from Middle Jurassic to Late Jurassic. Dilband Formation Dilband Formation which is about 20m thick in the type area (northern Kirthar range) was named by Abbas et al. (1998) and designated three members like lower Jarositic clay member (light grey to brown), middle ironstone member (reddish), and upper green glauconitic shale member. The Dilband Formation (synonym Mazar Drik Formation) is less than 30 m and exposed also in the Dilband Johan-Moola Zahri Range of Kirthan foldbelt and Loralai, Duki and Gadebar areas of Sulaiman foldbelt. It includes mostly the transitional and disconfirmable horizons representing Jurassic Cretaceous (J-K) boundary. This J-K boundary exposed in Duki, Loralai, Daman Ghar and Gadebar areas is represented by light brown shale alternated with light grey fresh colour and light brown weathered colour limestone belong to Dilband Formation. Its lower contact with Chiltan (Takatu/Zidi) Limestone and upper contact with Sembar Formation is disconfirmable and at places conformable. Ammonits from Mazar Drik and Moro area include Macrocephalites, Dolikephalites, Indocephalites, Pleurocephalites, Indosphinctes and Choffatia (Fatmi 1977). Arkell (1956) reported Bullatimorphites bullatus and Clydoniceras from the lower part of Mazar Drik unit/Dilband Formation, representing Late Bathonian age. Recently Malkani (2003c) has found dinosaurs (Brohisaurus kirthari) fossils from Sun Chaku (Karkh area) and Charoh (Zidi area) localities of Khuzdar district (Kirthar range) from the Dilband formation (transition beds of lower Sembar from Chiltan Limestone to Sembar shale). Its stratigraphic position tells the age range from Middle Jurassic to Late Jurassic. Its age can be considered as Late Jurassic. Early Cretaceous Parh Group The term Parh was first used by Blanford (1879) for rocks of Parh Range. The name was later applied by Vredenburg (1909) to a prominent white limestone in his Cretaceous succession. Williams (1959) redefined it as a limestone between the Goru and Mughal Kot formations. The type area lies in the Parh Range in the upper reaches of the Gaj River (lat. 260 54’ 45’’N; long. 670 05’ 45’’E). Goru and Parh formations are well exposed in the Goru and Parh ranges but the Sembar is well exposed in the Lakha Pir Charoh area just east of Parh Range. Parh Group represents Sembar, Mekhtar, Goru and Parh formations, however Mekhtar sandstone (Lower Goru Sandstone) is not 5 exposed in Parh range while it is exposed in Mekhtar area (Loralai District) and Murgha Kibzai area (Zhob District) of Balochistan and also found in subsurface in eastern Kirthar basin. Shah (2009) mentioned the Mona Jhal Group after the Fatmi et al. (1996) from Mona Jhal Anticline, 13 km north of Khuzdar and it includes the Sembar, Goru, Parh and Mughal Kot. According to the author’s opinion the Mughal Kot Formation is arenaceous clastic in the Eastern Sulaiman and fit with the Fort Munro Group which is mostly clastic, except Fort Munro Limestone. Sembar Formation The term Sembar Formation was proposed by Williams (1959) to replace the term Belemnite beds of Oldham (1890). The type section is Sembar Pass (lat. 290 55’ 05’’N; long. 680 34’ 48’’E). Malkani (2010a) reported three members of Sembar Formation in the Mekhtar and Murgha Kibzai area of Sulaiman Foldbelt like Sembar lower and upper shale members and middle member is named as Mekhtar member/Mekhtar sandstone member. The type locality of Mekhtar member is just south of Mekhtar town, near the Kareez (39F/7). This sandstone unit is about 100m thick. It is also found in the north of Mekhtar like Murgha Kibzai area. The shale is greenish grey and khaki, mostly calcareous, with rare glauconitic. The Mekhtar sandstone is Pab like white to grey, quartzose, thin to thick bedded and medium to coarse grained, mostly weathered as dark grey to black. The marl is grey to cream white, thin bedded and porcelaneous. Malkani and Mahmood (2016b) updated the Mekhtar member as Mekhtar Formation (Mekhtar sandstone or it is commonly called as lower Goru sandstone). Sembar Formation is estimated as about 1000m in the Loralai, Gadebar Range and Tor Thana areas. As lateral variation, this formation is relatively more and maximum thick in the Loralai, Tor Thana and Gadebar areas. It is being reduced in towards the Kirthar basin and Western Indus suture regions and also toward the northern Sulaiman Foldbelt. It is 133m thick in the type locality and 262m in the Mughal Kot area (Fatmi 1977; Shah 2009). It is about 200m near the Lakha Pir of Charoh anticline in Zidi area in the east of Khuzdar town. Its lower contact with the Loralai/Chiltan/Dilband formations is disconfirmable and at places conformable and upper contact with Goru formation is transitional and conformable. It contains foraminifers and most common belemnites Hibolithes pistilliformis, H. subfusiformis and Duvalia sp. From Windar River in Lasbela, Nuttal (in Arkell 1956) reported fragments of Virgatosphinctes denseplicatus and V. cf. V. subquadratus. The age varies from latest Jurassic to Early Cretaceous (Fatmi 1977). Mekhtar Formation (or Mekhtar Sandstone) Mekhtar Formation (or Mekhtar Sandstone or it is commonly called as lower Goru sandstone) is upgraded by Malkani and Mahmood (2016b) as formation (from previous Mekhtar member) due to its wide occurrence and lateral extension in the Eastern Sulaiman and also Eastern Kirthar basins (subsurface). It is not exposed in the Kirthar basin but found in subsurface, however it is exposed in Mekhtar and Murgha Kibzai areas of Sulaiman basin. Malkani (2010a) established three members of Sembar formation. But here the Middle Sandstone and upper shale and marl are considered as Mekhtar Formation. Its type locality is near the Mekhtar town just south of Mekhtar on Chamalang Mekhtar road (39F/7). At type locality it is round about 100m thick lensoid shape. This sandstone is oil producing/reservoir rocks in Kirthar basin commonly called Lower Goru Sandstone. Actually it is a Mekhtar Formation. It mostly consists of sandstone (Pab like) with some shale and marl. The lower contact with Sembar is gradational and sharp marked on Sandstone facies variation from Shale facies 6 of Sembar. The upper contact with Goru Formation is also sharp. According to law of superposition its age can be considered as Early Cretaceous. Goru Formation The term Goru Formation was introduced by Williams (1959). The type section is located near Goru village on the Nar river in the southern Kirthar Range (lat. 27 0 50’ 00’’N; long. 660 54’ 00’’E). It consists of alternations of about 3 thick marl units and two shale units. The shale is grey to khaki and calcareous. The marl is grey to cream white, thin bedded to thick bedded and porcelaneous. It is relatively reduced towards the axial belt regions. It is about 500m thick in the type area and also same in the Mekhtar area. It is being reduced towards western Indus Suture near Quetta upto 60m thick. Its lower contact with Sembar Formation is transitional and conformable where Mekhtar sandstone (Lower Goru Sandstone) is missing, otherwise its upper contact with Mekhtar sandstone is sharp. The upper contact with Parh Limestone is marked by a marine maroon red beds which also show conformable contact, however some author have suggested the maroon beds are indicator of disconformity but in actual these are marine red beds. The most of the fossils found belong to foraminifers and belemnite (Hibolithes spp.). Fritz and Khan (1967) described the foraminifers from Bangu Nala in Quetta as Globigerinelloides algeriana, G. breggiensis, G. caseyi, Ticinella roberti, Gavelinella, Rotallipora ticinensis, R. appennenica, R. brotzeni, R. reicheli, Praeglobo-truncana stephani and Planomallina buxtorfi. According to stratigraphic position, its age can be considered as Early Cretaceous. Parh Formation It consists of mainly limestone with minor shale and marly beds. Limestone and marl is cream white to grey, thin to thick bedded and porcelaneous. The shale is grey, khaki and calcareous. It is 60-70m thick in Sulaiman Basin. As lateral variation, this formation is relatively more and maximum thick (about 300-400m) in Karkh, Kharzan and the type locality areas of Kirthar Foldbelt. Its lower contact with Goru Formation is conformable and upper contact with Mughal Kot Formation is also transitional and conformable represented by about 12m marly beds. The formation is rich in foraminifers like Globotruncana Spp., G. ventricosa, G. lapparenti, G. sigali, Pseudotextularia elegans (Gigon 1962). The age of the Parh limestone is middle Cretaceous in the Sulaiman and Kirthar foldbelts, however it is maintained from middle Cretaceous to Late Cretaceous in the western Indus Suture (Axial Belt) areas where the Fort Munro Group is not developed and also lower and middle Sangiali group is not developed. For example the Ziarat Laterite showing K-T boundary is contacted by Cretaceous Parh Limestone and Paleocene Dungan Limestone. Late Cretaceous Fort Munro Group The term Fort Munro Group was first time used by Malkani (2009a) for Mughal Kot, Fort Munro, Pab and Vitakri formations. Its type section is Rakhi Gaj and Girdu are in Toposheet 39 K/1. The lower contact of this group is also found in Shadiani section in Toposheet 39 J/4. Mughal Kot Formation Williams (1959) named and designated the type section of the Mughal Kot Formation to be in the gorge 1-3 miles west of Mughal Kot post (lat. 310 26’ 52’’N; long. 700 02’ 58’’E). Its synonym is Nishpa formation. It has variable lithology like marly mudstone in the Rakhi Gaj area and its 7 vicinity, alternation of shale, lenticular sandstone and limestone in the Tor Thana and Murgha Kibzai area, and alternations of shale with subordinate sandstone is common in all other areas of eastern Sulaiman Foldbelt. In the western Sulaiman like the vicinity of Loralai, the Fort Munro Group is represented by about 100m shale further reducing to western Indus Suture belt, in the Ziarat laterite area, it is not developed. In the western vicinity of Ziarat, it is represented by shale and volcanics (Bibai Formation), and in the eastern vicinity of Quetta like Hana Lake and Sor Range areas it is represented by limestone with negligible shale. The shale is grey, khaki and calcareous and rarely noncalcareous. The sandstone is grey to white, quartzose to muddy, thin to thick bedded and medium to coarse grained, mostly weathered as dark grey to black. The marl and mudstone is grey to cream white. The Parh like limestone is creamy white, porcelaneous, thick bedded and lenticular observed in the Tor Thana area (39 F/3). It is estimated about 1200m in the Musa Khel and type locality area. Petroleum seep is reported in Toi River of Mughal Kot area, on the contact of Mughal Kot and Pab formations. As lateral variation, this formation is relatively more and maximum thick in the type locality and Musa Khel district. It is being reduced in towards the Kirthar basin and western Indus suture regions. It is mostly developed in shallow marine, prodeltaic and deltaic environments. Its lower contact with Parh Formation is transitional and conformable represented by marly beds well exposed in the Tor Thana and its vicinity areas, and upper contact with Fort Munro Limestone is also transitional and conformable, however where the Fort Munro Limestone is absent its upper contact with Pab sandstone is transitional. Williams (1959) reported Omphaocyclus sp. and Orbitoides sp. showing Maastrichtian ages, while Marks (1962) reported Siderolites cf. calcitrapoides, Orbitoides tissoti minima and O. tissoti compressa from upper part of Mughalkot formation in Rakhi Nala showing late to middle Campanion age, so its lower part may extends up to early Campanion. So its age is Early to Late Campanion Fort Munro Formation The name Fort Munro limestone member was introduced by Williams (1959) for the upper dominantly limestone unit of the Mughal Kot Formation and he designated the type section in the western flank of the Fort Munro anticline along the Fort Munro-Dera Ghazi Khan road (lat. 290 57’ 14’’N; long. 700 10’ 38’’E). Fatmi (1977) assigned it a separate formation status because of its distinct lithology and regional extent. It consists of grey to brown and thin to thick bedded limestone with minor greenish grey shale. It is 100m thick at type locality, 248m in subsurface at Dabbo Creek i,e due to dip it actual thickness may be 100-150m. The lower contact with Mughal Kot Formation and upper contact with Pab Formation are transitional and conformable. Blanford (1879) correlated the unit with Hippuritic limestone of Iran on the base of fragments of Hippurite found from the scree of this unit. Williams (1959) reported Omphaocyclus sp. and Orbitoides sp. showing Maastrichtian ages. HSC (1961) reported Actinosiphon punjabensis, Orbitoides media, Siderolites sp. etc from Kirthar range and assigned Maastrichtian gae. According to Williams (1959), HSC (1961) and Marks (1962, its age may be late companion to Early Maastrichtian. Pab Formation The term Pab Sandstone was introduced by Vredenburg (1907) and the type section in the Pab Range (lat. 250 31’ 12’’N; long. 700 02’ 58’’E) was designated by Williams (1959). Malkani (2006d) divided the Pab Formation into three members like lower Dhaola member (Dhaola Nala, lat. 29 0 42’ 41’’N; long. 690 29’ 48’’E), middle as Kali member (Kali hills of Dhaola Range, lat. 29 0 42’ 41’’N; 8 long. 690 29’ 42’’E) and upper Vitakri member). The best reference section for Dhaola member is Fort Munro area (lat. 290 57’ 14’’N; long. 700 10’ 38’’E) of D.G.Khan district, and for Kali member is Tor Thana area (lat. 300 12’ N; long. 690 11’E) of Loralai District. The Dhaola member (white quartzose sandstone with minor to moderate black weathering) represents the environments of proximal delta, near the coastline and consistent in the eastern Sulaiman Foldbelt. Kali member (shale and black weathering sandstone) represent middle and distal deltaic environments and mostly exposed in the western part of Sulaiman Foldbelt. Two members are not consistent every where in the Sulaiman basin. In the Dhaola and Chamalang sections, both Dhaola and Kali member are existed well. The thickness of Pab Formation is estimated 500m in the Fort Munro area. It is pinching toward north like Mughal Kot section (300m), and also pinching toward south in the Khairpur- Jacob Abad high. This high separates the northern delta (Sulaiman Basin) from southern delta (Kirthar Basin). In the western Kirthar it is about 600m or more thick. It is not absent in MariBugti Hills but shale proportion increases. The thickness of this formation is relatively less in the Mughal Kot and toward north and Western Indus Suture (WIS) but uniform in the eastern Sulaiman Foldbelt. Its lower contact with Fort Munro Limestone or Mughal Kot Formation (when Fort Munro Limestone is absent) is transitional and conformable and upper contact with Vitakri is disconfirmable, when Vitakri Formation is missing, its upper contact with Sangiali/Rakhi Gaj Formation is conformable. Vredenburg (1908) reported Orbitoides (Lepidorbitoides) minor from lower part of the unit in Rakhi Nala representing early Maestrichtian age. Williams (1959) reported mixed bentonic-pelagic foraminifers of Maestrichtrian age from type locality area. HSC (1961) reported Globotruncana aff. G. linnei, Lituola sp., Omphalocyclus macropora, Orbitella media, Orbitoides sp., Siderolites sp., from Moro area with Maestrichtian age. Recently, dinosaurs, crocodiles and pterosaurs are found from Vitakri Formation (Previously upper member of Pab formation, for detail see in Vitakri Formation) of Sulaiman foldbelt. The fossil of gymnosperm/conifer wood of Baradarakht goeswangai Malkani 2014, with 20 cm in diameter, is found from the Latest Cretaceous (Maastrichtian) Pab Formation in Goeswanga Pass, Barkhan District, Balochistan (Malkani 2014f). According to dinosaur fossils and stratigraphic position, the age is considered as Middle to Late Maastrichtian. Vitakri Formation Malkani (2006c) introduced first time the upper member of Pab Formation as Vitakri member and Malkani (2009a) upgraded this member into Vitakri Formation (Type Vitakri area, lat. 29 0 41’ 19’’N; long. 690 23’ 02’’E) due to its distinct lithology, depositional environments and lateral extension. Vitakri village is about 30 Km in the south-southwest of Barkhan town. Vitakri Formation (15-35m, extended mostly in the eastern Sulaiman Fold and Thrust Belt) consist of alternated two units of red mud/clay (2-15m each unit) of over bank flood plain deposits and two quartzose sandstone units (2-15meach unit) with black weathering of meandering river system. Lower red mud horizon is based on Kali member or Dhaola member and capped by middle sandstone horizon of Vitakri Formation. The upper red mud horizon is based on middle sandstone horizon and capped by a resistant sandstone horizon. Its coeval strata (coal, carbonaceous shale and sandstone) represent the lacustrine and deltaic environment, and laterite represent the erosional disconformity. The sandstone is white to grey, thin to thick bedded and fine to coarse grained, quartzose, mostly weathered as dark grey to black. The shale is red, maroon, and greenish grey and calcareous to noncalcareous. The red muds of this disconformity and just below this are the host of latest Cretaceous dinosaurs in 9 Pakistan. Vitakri Formation is regional extension in eastern Sulaiman Foldbelt and also Ziarat laterite is a part of Vitakri Formation. Vitakri Formation was the Park for the latest Cretaceous dinosaurs and crocodiles of Pakistan. Its lower and upper contact with Pab and Sangiali formations is disconfirmable. The Vitakri Formation has dinosaurs, mesoeucrocodiles and pterosaurs and invertebrates like fresh water bivalves, etc. More fossil plants may be found further from the Kingri coal of Vitakri Formation (Malkani 2014f). Pakistan appeared for the first time on the world dinosaur’s map based on recent geological and paleontological exploration. The Mesozoic strata and their internal and external boundaries are well exposed in the Lower, Middle and Upper Indus basins of Pakistan which allowed the discoveries of numerous remains of dinosaurs and associated vertebrates. The lower Indus (Kirthar) Basin yielded a partial rib and an egg of the Cretaceous Mesoeucrocodile Khuzdarcroco zahri and few remains of Late Jurassic titanosauriform or early titanosaurian sauropod dinosaur Brohisaurus kirthari. Furthermore, the lower Indus basin yielded a footprint of a Middle Jurassic titanosauriform/early titanosaurian sauropod. The red muds of the Latest Cretaceous Vitakri Formation of Middle Indus (Sulaiman) Basin yielded well developed and well preserved remains of the herbivorous pakisaurids Khetranisaurus barkhani, Sulaimanisaurus gingerichi and Pakisaurus balochistani, of the balochisaurids Marisaurus jeffi, Balochisaurus malkani and Maojandino alami, of the saltasaurids Nicksaurus razashahi, as well as of the most advanced and large-sized titanosaurian sauropod dinosaurs Gspsaurus pakistani and Saraikimasoom vitakri. Carnivorous large bodied abelisaurians Vitakridrinda sulaimani and small bodied noasaurian theropods Vitakrisaurus saraiki have also been identified, as well as carnivorous large to medium bodied mesoeucrocodilians Sulaimanisuchus kinwai of Sulaimanisuchidae and large bodied Pabwehshi pakistanensis and Induszalim bala of Induszalimidae. Other fossil remains include the toothed pterosaur Saraikisaurus minhui and a wood fossil of the conifer Baradarakht goeswangai. Further titanosaur (Pashtosaurus zhobi) trackways have been found on the thick sandstone bed of the Latest Cretaceous Vitakri Formation of Western Sulaiman basin and eastern extremity of Western Indus Suture as well as bony remains of the titanosaurs found in the same basin and same formation. Pakiring kharzani Malkani 2014 (bivalves) is found from the Cretaceous-Paleogene (K-Pg) boundary laterite/thin rust on the last bed of Pab sandstone and it belongs to Vitakri Formation in the Kharzan area of Khuzdar district (Malkani 2014f). It is sub ring type and rough surface ornamented bivalves with rope like shape. According to dinosaur fossils and stratigraphic position, the age is considered as Latest Maastrichtian or Latest Cretaceous (67-66Mya). Paleocene Sangiali Group Malkani (2009a) introduced Sangiali Group representing Sangiali, Rakhi Gaj and Dungan formations. The type section (Sangiali village area, lat. 290 41’ 53’’N; long. 690 23’ 54’’E) is exposed just 1km south southeast of Village Sangiali. Sangiali Village is 4km north of Vitakri Village. Sangiali Village is about 26 Km in the south-southwest of Barkhan town. The best and easily approachable reference section (close to type locality of Kingri Formation) is about 5km in the northwest of Kingri town (39F/15). The Khadro Formation of Kirthar Foldbelt has much volcanics. In Sulaiman Range there are no volcanics but its green shale and sandstone may be glauconitic or may show some volcanic source. Further the dominant sandstone in Khadro can hurdle for 10 identification of Rakhi Gaj formation. Further the upper sequence is again different from Ranikot group. It is about 30m thick in the type area and it is being reduced on every side from type locality area but existed in the eastern Sulaiman Foldbelt. Sangiali Formation and Group is suggested to remove the problems. Mesozoic in Sulaiman and Kirthar are closely resemble while Paleocene is different because the Bara and also part of Khadro formations were deposited by fluvial to deltaic while in the Sulaiman the deposition was marine and deltaic. Sangiali Formation Malkani (2009a) introduced first time the Sangiali Formation (due to its distinct lithology, depositional environments and lateral extension) with type section (Sangiali village area, lat. 290 41’ 53’’N; long. 690 23’ 54’’E) exposed just 1km south southeast of Village Sangiali. It is extensive in most part of eastern Sulaiman Foldbelt and consists of green shale and sandstone with resistant brown limestone. The shale is found in the lowermost part, which is graded in to sandstone. The sandstone is capped by limestone. The shale is green and glauconitic and may be phosphate bearing. The sandstone is greenish grey to grey and white and thin to medium bedded. The limestone is brown, thin to thick bedded and bivalves bearing. The Sangiali Formation is 30m thick at the type locality and pinching into few metres beds toward all vicinity areas. Nautiloids are common in the type and just south in Vitakri area. Its lower contact with Vitakri Formation is disconfirmable and upper contact with Rakhi Gaj Formation is transitional and conformable. The Nautiloids and bivalves are common in this formation found from the Sangiali and Vitakri area. Pakiwheel vitakri Malkani 2014, the stocky type nautiloids is found just after the K- Pg boundary in Sangiali Formation close to east of Vitakri town (Malkani 2014f), and Pakiwheel karkhi Malkani 2014, the slender type nautiloids, is found in the green mudstone, may be of volcanic origin, of the Early Paleocene Sangiali Formation, 5 km east of Karkh town (Malkani 2014f). Eames (1952) reported Early Paleocene fossils from Rakhi Nala. The possible bony fishes, the Teleostei or holostei fish or ichthyosaur Karkhimachli sangiali Malkani 2014 are found fragmentary on the Early Paleocene part of Sangiali Group of Karkh area of Khuzdar District but its nearby higher areas consists of Late Cretaceous Mughalkot and Pab formations. Its preserved portion mostly belongs to body cross section having herring bone type structure. It is small sized fish/ichthyosaur. Further some cross sections are also referred to it. A body cross section of marine fish found in the Jurassic Chiltan Limestone of Kharzan of Mula-Zahri area, Kirthar Range (Malkani 2014f). So its age is considered as Early Paleocene. Rakhi Gaj Formation Williams (1959) introduced the lower Rakhi Gaj shales. The Rakhi Gaj formation is mentioned by Shah (2002). The Rakhi Gaj Formation is also used by the present author in many Geological maps. Upon the suggestions of S.M.Hussain of American Oil Company, the Stratigraphic Committee (Shah 2009) has adopted the name Girdu Member for the Gorge beds of Eames (1952). The Rakhi Gaj Nala is designated as the type section (Lat. 290 57’ 14’’ N; Long. 700 11’ 30’’ E). Malkani (2010a) reported two members of Rakhi Gaj formation like lower Girdu member (Gorge beds) and upper Bawata members (Fig.1g in Malkani 2010a). It is the middle formation of Sangiali Group and lower formation where Sangiali Formation is absent. The Girdu member is about 100m thick at type area (Lat. 290 57’ 27’’ N; Long. 700 04’ 40’’ E) where it consists of thick and resistant beds of sandstone with minor shale. The sandstone is grey, greenish grey, thin to thick bedded and fine to coarse 11 grained, bivalve bearings, hematitic and glauconitic weathered as dark reddish grey to dark grey. Iron and potash from glauconitic and hematitic sandstone seems to be significant especially in the Fort Munro, Rakhi Gaj and its vicinity areas of eastern Sulaiman Foldbelt. The Bawata member named by Malkani (2010a) to fill the missing link. This upper member can be named Rakhi Gaj member which lacks the well developed contact with Dungan Formation while Bawata locality has well developed contact with Dungan Formation. The Bawata member (Bawata as type section; Lat. 300 00’ N; Long. 690 57’ 30’’ E) consists of mainly shale along with alternation of sandstone (Fig.1g in Malkani 2010a) is about 200m thick. The Shale is common in the uppermost part. The shale is grey, khaki and calcareous. The sandstone is greenish grey to grey, bivalves and iron bearings. The shale and sandstone of Fort Munro area show green colour may due to glauconitic or igneous origin from volcanism of Deccan trap. The Girdu member is about 100m and Bawata member is about 200 m in its type areas. Both members are exposed in the eastern Sulaiman Foldbelt and its contact is transitional. The lower contact of Girdu member with Sangiali and upper contact of Bawata member with Dungan Formation is conformable. The lower contact of Rakhi Gaj Formation with Vitakri Formation and Pab Formation (when Vitakri and Sangiali both are absent) is disconformable. Eames (1952) reported Corbula (Varicorbula) harpa, Leionucula rakhiensis, Venericardia vredenburgi, Tibia (Tibiochilus) rakhiensis and other fossils from Rakhi Nala with Early Paleocene age. Abundant Cardita (Venericardia) beaumonti of Danian age reported many works from different areas. Nagappa (1959) reported Globogerina pseudobulloides and G. triloculinoides. Sohn (1959) recorded ostracodes such as Howecythereis multispinosa, H. micromma and Paracypris rectoventra from Laki Range. HSC (1961) also reported many list of foraminifers. Latif (1964) has reported pelagic foraminifera possibly from the Rakhi Gaj Formation of Rakhi Nala. Its age is considered as middle Paleocene due to stratigraphic positions. Dungan Formation The term Dungan limestone was introduced by Oldham (1890). Williams (1859) designated the type section to be near Harnai (lat. 300 08’ 38’’N; long. 670 59’ 33’’E) and renamed the unit Dungan Formation. It consists of limestone, shale and marl. The limestone is grey to buff, thin to medium bedded and conglomeratic. Shale is grey, khaki and calcareous. The marl is brown to grey, thin to medium bedded and fine grained. This formation is 50-300m maximum thick. Laterally this formational facies is more diverse, at places thick limestone deposits while at places minor limestone showings. The Sui main limestone is an upper part of Dungan limestone due to its variable behavior. It is thick in the Zinda Pir, Duki, Sanjawi, Harand, and also in Mughal Kot section but negligible as in Rakhi Gaj and Mekhtar areas. Petroleum showings are common in this formation especially in the Khatan area (Oldham 1890). Its lower contact with Bawata member of Rakhi Gaj Formation is conformable, near the western Indus Suture belt it has disconformity at the base, while the upper contact with Shaheed Ghat Formation is transitional and conformable. It has many mega forams. It age is considered as Late Paleocene, rarely exceeding to early Eocene. However it is maintained all Paleocene in the Ziarat area and the Western Indus suture (Axial belt) areas where the Sangiali and Rakhi Gaj formations i.e. the lower and middle Sangiali group is not developed. For example the Ziarat Laterite showing K-T boundary is contacted by Parh and Dungan formation. A rich fossil assemblage including foraminifers, gastropods, bivalves and algae are reported by Davies (1941), Khan M.H. (in Lexique 1956), HSC (1961), Latif (1964), Iqbal (1969a) and others. Khan M.H. (in Lexique 1956) reported presence of rich assemblages of foraminifers (Davies 1927; Nuttal 1931), 12 corals (Duncan 1880), mollusces (Vredenburg 1909, 1928b) and echinoids (Duncan and Sladen 1882). The foraminifers include Nummulites nuttali, N. thalicus, N. globules, N. sindensis, Assilina ranikotensis, Miscellanea miscella, M. stampi, Lockhartia haemei, Lepidocyclina (Polylepidina) punjabensis and Discocyclina ranikotensis. Foraminifers are generally abundant and most of these belong to Fasciolites, Nummulites, Coskinolina, Dictyoconoides, Linderina, Lockhartia, Operculina, Miscellanea, Globorotalia, Cibicides, etc. Species like Miscellanea miscella, M. stampi, nummulites nuttali, n. thalicus, N. sindensis, Assilina dandotica, Kathina selveri and Lockhartia tipper indicate Paleocene to Early Eocene age which is also confirmed by some algae such as Distichoplax sp., Lithothamnium sp., Mesophyllum sp. However now these fossils and law of superposition suggests the age of this formation as Late Paleocene. Early Eocene Chamalang (=Ghazij) Group The term Chamalang Group was first used by Malkani (2010a). The term Ghazij was introduced by Oldham (1890). Williams (1959) proposed that the type section be at Spintangi (lat. 290 57’ 06’’N; long. 680 05’ 00’’E) and used the term Ghazij formation. It is upgraded as group by Shah, (2002). Chamalang (Ghazij) group represents Shaheed Ghat, Toi, Kingri and Baska formations. Drug and Kingri formations are not well developed in the Spintangi area, so the Malkani (2010a) suggests for the Chamalang Group where all the formations of Ghazij group are well developed along with new formation like Kingri Formation. The type section for Chamalang Group is the Chamalang area (lat.300 10’ N; long. 690 25’ E). Shaheed Ghat Formation Sibghatullah Siddiqui, Jamiluddin, I.H. Qureshi and A.H. Kidwai (1965) (verbal communications with Sibghatullah Siddiqui and Jamiluddin) used the name Shaheed Ghat Formation for the upper Rakhi Gaj and green nodular shales of Eames (1952). The type locality is Shaheed Ghat, Zinda Pir area of Dera Ghazi Khan District (lat. 300 24’N; long. 700 28’E). It consists of mainly shale/mud with negligible silt and sandy beds. The shale is grey, greenish grey, khaki and calcareous. The shale is rarely intercalated with silty and sandy lenses. The formation contains thin limestone beds in the upper part with nummulites, gastropods and lamellibranchs. The thickness of this formation is estimated 500m in Sulaiman and northern Kirthar foldbelt. The thickness of this formation is relatively slightly less than the other exposures in eastern Sulaiman Basin. Mulastar zahri Malkani 2014, a star fish (Malkani 2014f), two pectin type other bivalves, 3 gastropods and 1 coral like fossils are found from Shaheed Ghat Formation of Kharzan area, Mula-Zahri range. Its lower contact with Dungan and upper contact with Toi Formation (in the coal bearing areas like Johan and Mach) or Drug Formation (when Toi and Kingri formations are absent especially in the Karkh area) are conformable. This formation contains foraminifera, gastropods and bivalves. The pelecypods include Venericardia pakistanica, Lucina yawensis, Corbula (Bicorbula) subexarata, C.(B.) paraexarata and gastropods include Crommium polihathra, Turritella (stiracolpus) harnaiensis, Chondrocerithium pakistanicum, Gisortia cf. G. murchisoni (Iqbal 1969b). These fossils and Siddiqui et al (1965) suggested Early Eocene age. Toi Formation The Toi Formation has been formalized after S. M. Hussain of American Oil Company’s briefing and verbal communication before the stratigraphic Committee of Pakistan (Shah, 2002). The Shah 13 (2002) mentioned the Mughal Kot type locality with wrong grid reference, while correct references seams to be (lat. 310 29’ N; long. 700 07’E). Its name is derived from the Toi River/Nala flowing near the Mughal Kot locality. It consists of sandstone, greenish grey to grey shale and white to light brown marl/rubbly limestone along with some coal. The sandstone is greenish grey to grey and thin to thick bedded. The shale is greenish grey, khaki and calcareous. The marl or limestone is white to light brown and rubbly. The coal is sub bituminous and have metallic luster. It is exposed in the Mach and Johan area located in the northern part of eastern Kirthar basin. The thickness of Toi Formation is about 600m in the type area of Mughal Kot section and about 1200m in the Kingri, Bahlol and Chamalang sections. The lower contact of Toi Formation with Shaheed Ghat Formation is conformable while the upper contact with Kingri formation is disconfirmable. It has many fossiliferous sandstone/coquina beds. Malkani (2014f,2015c) and Malkani and Sun (2016) reported Bolanicyon shahani from Mach coal mine area. Bolanicyon shahani Malkani 2014 (Quettacyonidae) is found (Malkani 2014f) at the coal mining at depth of about 500m in the Early Eocene Toi Formation of south western Mach (Gishtari) area. Its 1 incisor, 1 canine, 4 premolar and 3 molar teeth are preserved (Malkani and Sun 2016). According to its stratigraphic position and fauna, its age can be considered as Early Eocene. Kingri Formation The tem Kingri Formation was first used by Malkani (2009a). The type section of Kingri formation is the just northwest of Kingri town (lat. 300 28’ N; long. 690 47’E). It consists of reds shale/mud with subordinate grey sandstone. The shale is mostly red and maroon and sandy and silty and calcareous. The sandstone is grey to light brown, thin to thick bedded. It is exposed in the Mach and Johan area located in the northern part of eastern Kirthar basin. The thickness of this formation is estimated about 700m in the type section of Kingri (Musakhel district Balochistan) and also same in Shirani section (FR D.I.Khan, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa). It extends toward Mach and Johan (Kalat), Balochistan in the southwest and also extends in the north upto Hangu (Kohat sub basin) where it is called Gurguri snadstone. It represents the flood plain or overbank fines along with channel sandstone. It is pinching rapidly eastward and absent in areas of D.G. Khan, Rajan Pur and Dera Bugti districts. Its lower contact with Toi and upper contact with Drug Formation are disconfirmable. Gingerich, et al (2001) has also found a unique mammalian fauna from the Kingri/Toi formation of Gandhera (Kingri) area. According to its stratigraphic position, its age can be considered as Early Eocene. Drug Formation Sibghatullah Siddiqui, Jamiluddin, I.H. Qureshi and A.H. Kidwai (1965) (verbal communications with Sibghatullah Sidique and Jamiluddin), and Iqbal (1969) used the name Drug Formation for rubbly limestone of Eames (1952). The type section (lat. 30 0 49’ 15’’N; long. 700 12’ 30’’E) has been designated in Drug Tangi located about 3 km southeast of Drug village (Shah, 2002). The Shah (2002, 2009) mentioned the wrong order or position of Ghazij group formations like Toi and Drug formations. The actual position of Toi Formation is below the Drug Formation while Shah (2002, 2009) mentioned every where the Toi formation is above the Drug formation. It is confirmed in the north and southwest of Sulaiman province. It consists of limestone, marl and shale. The limestone and marl is chalky white to light brown and grey, rubbly and thin to thick bedded. The shale is grey, khaki and calcareous. The formation is maximum thick in the core of Sulaiman foldbelt like Baghao 14 and Rar Khan Areas of Barkhan District and estimated about 200-300m thick. It is being reduced in all directions from these maximum thick areas. It is absent in the Western Indus Suture and also in Mughal Kot section of Sulaiman Foldbelt and further north. It is exposed in the Mach and Johan area located in the northern part of eastern Kirthar basin. Its lower contact with Shaheed Ghat Formation in the easternmost and southeastern Sulaiman Foldbelt is transitional and conformable, and upper contact in the northeast, central and western Sulaiman Foldbelt is disconfirmable with the Kingri Formation, and in the eastern and southeastern Sulaiman Foldbelt the upper contact with Baska Formation is conformable and marked at the first bed of alabaster gypsum. The Drug limestone and shale is the host of celestite mineralization in Sulaiman Foldbelt. It has many fossiliferous sandstone/coquina beds especially in the Chamalang area. Iqbal (1969b) reported gastropods like Euspirocrommium oveni, Cancelluluria soriensis, Ringicuia pseudopunjabensis, and a pelecypod Lucina exquiscia. These fossils and Siddiqui et al (1965) suggested Early Eocene. Baska Formation The name Baska shale is proposed by the Hemphill and Kidwai (1973) to replace the descriptive term “shale with alabaster” of Eames (1952). Hemphill and Kidwai (1973) designated the type section exposed about 2 km east-northeast of Baska village (lat. 310 29’N; long. 700 08’E). It consists of gypsum, shale, limestone, marl and rare siltstone. The gypsum is grey to grayish white, medium to thick bedded and massive. . Shale is grey, khaki and calcareous. The marl is cream white, thin to medium bedded and porcelaneous. Its thin exposure is found in the Mach area located in the northern part of eastern Kirthar basin. Further southward it is not reported. The siltstone is greenish grey to grey and thin to medium bedded. Its thickness is estimated variable from 100m to 30m. As lateral variation, this formation is relatively more and maximum thick than the other exposures in the Chamalang, Nisau, Manjhail, Toi Nala, Toi River and Barkhan areas and minimum thick in the south eastern and southern Sulaiman located in the central core of Sulaiman Basin. Its lower contact with Drug Formation and upper contact with Habib Rahi Formation are conformable. It has many fossiliferous rubbly limestone beds especially in the Chamalang and Mughal Kot sections. Iqbal (1969b) reported foraminifers like Cuneoline sp., Lockhartia hunti, and Dictyoconoides vredenburgi, pelecypods like Bulsella sp., A. Eames and Barbatia drougensis, the later being restricted to Early Eocene, gastropods like Euspira cf. E. punjabensis and Gosavia humberti. Its age is Early Eocene. Kirthar Group It was initially introduced as Kirthar Series by Blanford (1876) after the Kirthar Range to describe Eocene strata between his Ranikot group and Nari in western Sind while Noetling (1905) separated the lower part as Laki series and retained the name Kirthar for the upper part only. The term Kirthar Group is being used here for the Kirthar and Gorag formations. Kirthar group in western Kirthar Basin is correlated with Laki Formation (upper formation of Laki Group) of eastern Kirthar basin (Laki range and surroundings), Kahan group (Habib Rahi, Domanda, Pirkoh and Drazinda formations) of Sulaiman Basin and Kohat sub basin, and Sakesar limestone of Nammal Group. Its age is late Early-Middle Eocene. Kirthar Formation It is named by Cheema et al. (1977) and now it comprises of mixed lithology like shale, marl, limestone of lower Kirthar member of Brahui limestone (HSC, 1961). Its lower contact with 15 Kingri/Shaheed Ghat formations are transitional and conforable. The Formation contains foraminifers, gastropods, bivalves, echinoids and algae reported by Noetling (1905), Nuttall (1925), Davies (1926), Haque and Khan (in Lexique 1956), Haque (1962a), HSC (1961) and Iqbal (1973). The foraminifers include Assilina granulose, A. pustulosa, Lockhartia hunti, var. pustulosa, Flosculina globosa, Opertorbitolites douvillei, Fasciolites oblonga, Linderina brugesi and Dictyoconoides vredenburgi, important mollusces include Gisortia murchisoni, Velates perversus, and Blagraveia sindensis and echinoids include Amblypygus subrotundus and Echinolampas nummulitica. These fossils indicate an Early Eocene (Ypresian) age. Hunting Survey Corporation/HSC (1961) reported middle Eocene fauna like Actinocyclina alticostata, Assilina cancellata, A. rota, A. irregularis, Nummulites beaumonti, N. gizehensis, Dictyoconoides cooki and Early Eocene fauna like Assilina laminose, Coskinolina balsilliei and Dictyoconoides vredenburgi. So its age is Early Eocene to middle Eocene. Gorag Formation It is originally named as Gorag member of Brahui limestone by HSC (1961) after Gorag peak in south of Gaj river in Kirthar range and it consists of resistant and peak forming limestone with negligible shale and marl. It is well recognised in the Kirthar Range. This formation include the Laki limestone member (following Laki limestone named after Laki Range and Laki village by Nuttal 1925, and Laki limestone member of Brouwers and Fatmi 1993) which is 200-300m thick exposed as prominent scarp on flanks of Laki Range, hills south of Hyderabad and near Thano Bula Khan. There was confusion in the Laki limestone member (upper part of Laki Group) and Kirthar limestone in the Laki Range, Hyderabad and Thano Bula Khan Areas. Now this confusion is removed by correlating Gorag limestone with Laki limestone member which is thick upto 200m. Its lower contact with Kirthar and upper contact with Nari Formation is transitional and conformable. It contains foraminifers, gastropods, bivalves, echinoids and algae reported by Noetling (1905), Nuttall (1925), Davies (1926), Haque and Khan (in Lexique 1956), Haque (1962a), HSC (1961) and Iqbal (1973). The foraminifers include Assilina granulose, A. pustulosa, Lockhartia hunti, var. pustulosa, Flosculina globosa, Opertorbitolites douvillei, Fasciolites oblonga, Linderina brugesi and Dictyoconoides vredenburgi, important mollusces include Gisortia murchisoni, Velates perversus, and Blagraveia sindensis and echinoids include Amblypygus subrotundus and Echinolampas nummulitica. These fossils indicate an Early Eocene (Ypresian) age. Hunting Survey Corporation/HSC (1961) reported middle Eocene fauna like Actinocyclina alticostata, Assilina cancellata, A. rota, A. irregularis, Nummulites beaumonti, N. gizehensis, Dictyoconoides cooki and Early Eocene fauna like Assilina laminose, Coskinolina balsilliei and Dictyoconoides vredenburgi. So its age is late Early Eocene to middle Eocene. Gaj Group To remove missing link the Gaj group is here being established after the Gaj River in Kirthar Range for the Nari and Gaj formations. Duncan and laden (1884, 1886), Vredenburg (1906b, 1909b), Nuttall (1925, 1926), HSC (1961), Pascoe (1963) Khan M.H. (1968) and Iqbal (1969a) reported foraminifers, corals, mollusks, echinoid, algae and other fossils. The foraminifers include Nummulites intermedius, N. vascus, N. fichteli, N. clypeus, Lepidocyclina (Eulepidina) dilatata, etc., bivalves include Crassatella sulcata, Venus (Ventricola) multilamella, V. (Antigona) peepera, gastropods include Scaphander oligoturritus, Lyria anceps and Tritonsium (Saia) indicum. Pascoe 16 (1936) concluded Stamian of Europe and ranges from Rupelian to Chattian. Khan (1968) assigned Rupelian to early Aquitanian age. HSC (1961) assigned the age of this group as Oligocene to Miocene. Nari Formation It was named by Williams (1959) for the Nari Series by Blanford (1876) after the Nari river. It consists of marine brown sandstone, red, brown and yellow shale, and brown limestone. It is equalent to Chitarwata formation of Sulaiman Basin. Its lower contact with Gorag and upper contact with Gaj Formation is transitional and conformable. Fossils details are also mentioned in the above Gaj group. Its stratigraphic position and above mentioned fauna tells Oligocene age. Gaj Formation It was named by Williams (1959) for the Gaj Series by Blanford (1876) after the Gaj river. It consists of estuarine to terrestrial deposits dominantly varicoloured shale with subordinate sandstone and limestone. It mostly resembles with Nari formation however the contact is being marked at the end of massive sandstone and at the start of dominant shale lithology. It is correlative to Early Miocene Vihowa Formation of Sulaiman basin. Its lower contact with Nari is conformable and upper contact with Litra/Chaudhwan Formation is disconformable. Fossils details are also mentioned in the above Gaj group. Its stratigraphic position and above mentioned fauna tells Miocene age. Manchar Group The term Manchar is derived from Manchar series of Blanford (1876) after the Manchar lake a few kms west of Sehwan. Late Miocene to Pliocene Manchar group represents Litra Formation and Chaudhwan Formation. The Litra formation is exposed in the Sor Range-Deghar syncline and also on the eastern foothills of Kirthar Range. The Sor Range-Deghar syncline is a transition zone/boarder zone of Sulaiman and Kirthar basins. The Sor Range-Deghar syncline is located in the east of Quetta town. The Manchar group is mostly equalent to upper part of Vihowa Group (Litra and Chaudhwan formations). These are exposed in the eastern foot mountains of Kirthar and Laki ranges. Litra Formation The Litra Formation was first used by Hemphill and Kidwai (1973). The type section designated to be Litra Nala (lat. 310 01’N; long. 700 25’E). It consists of sandstone with subordinate shale and conglomerate. The sandstone is grey, thin to thick bedded and massive, fine to coarse grained, gritty and calcareous. The shale is maroon, khaki and calcareous. The conglomerate is thin to thick bedded and dominantly sandy and calcareous. Its lower contact with Gaj/Laki/Kirthar/Gorag Formation and upper contact with Chaudhwan Formation is disconfirmable or angular. This formation is the host of continental vertebrates. Raza et al. (2002) placed the lower age of Litra formation at 11 Ma based on Hipparaion in the lower part of this formation. They also estimated the age of Litra Formation from 11 to 6 Ma i.e. Late Miocene. Chaudhwan Formation The Chaudhwan Formation was first used by Hemphill and Kidwai (1973). The type section designated to be in Chaudhwan Zam (lat. 310 37’N; long. 700 15’E). It consists of alternated 17 mudstone/shale, sandstone and conglomerate. The mudstone/shale is maroon, khaki and calcareous. The sandstone is grey, brown, thin to thick bedded, fine to coarse grained, gritty and calcareous. The conglomerate is thin to thick bedded and dominantly sandy and calcareous. Thick conglomerate beds with some mud and sands cap the upper part of this formation. These are exposed in the eastern foot mountains of Kirthar and Laki ranges. Its lower contact with Litra Formation is disconfirmable while upper contact with Dada Formation is angular and at places transitional and marked at the start of dominant and resistant conglomerate. This formation is the host of continental vertebrates. According to stratigraphic position, its age is Pliocene. Sakhi Sarwar Group The term Sakhi Sarwar Group was named by Malkani (2012h) for Pleistocene Dada (mainly conglomerate) and Holocene Sakhi Sarwar (clays, silt, sandstone and conglomerate) formations (Malkani 2012h). These are exposed in the eastern foot mountains of Kirthar and Laki ranges. Dada Formation Its name is derived from Dada River south of Spintangi Railway station (HSC, 1961). It consists of conglomerate with subordinate shale and sandstone. At places it also includes the white and red muds especially in the valley areas. Its lower contact with Chaudhwan Formation and upper contact with Sakhi Sarwar Formation is angular and at some places transitional. According to stratigraphic position, its age may be Pleistocene. Sakhi Sarwar Formation It was named by Malkani (2012h) for the varicoloured clays, sandstone, siltstone and conglomerate. Its lower contact with Dada Formation and upper contact with subrecent alluvium is angular and at places transitional. Its age is Holocene. Subrecent and Recent surficial deposits These are represented by alluvial deposits in the footmountains (Daman) and plain areas deposited by Indus river systems. Some minor eolian sand dunes are found in the coastal areas. In the vicinity of high mountan ridges the colluvium scree and talus are also found. REVISED STRATIGRAPHY OF EASTERN KIRTHAR BASIN (LAKI RANGE AND SURROUNDINGS), SINDH PROVINCE Eastern Kirthar basin (Laki anticline and eastward upto Nagar Parker Igneous complex) as name shows it is located in the eastern part of Kirthar basin, on the west it is bounded by western Kirthar, on the east by Nagar Parker segment of Indo-Pak shield, on the south by Indo-Pak Ocean and on the north by Sulaiman basin. Eastern Kirthar basin represents exposed Late Cretaceous Pab and Latest Cretaceous Vitakri Formation of Fort Munro Group in the core of Laki anticline and on the limbs Cenozoic rocks. However in subsurface the older Mesozoic, Triassic, Paleozoic and Precambrian rocks may be found. The exposed stratigraphic sequences in the eastern Kirthar basin under the Sindh Province are being described as follows. 18 Late Cretaceous Fort Munro Group The term Fort Munro Group was first time used by Malkani (2009a) for Mughal Kot, Fort Munro, Pab and Vitakri formations. Its type section is Rakhi Gaj and Girdu are in Toposheet 39 K/1. Here only Pab and Vitakri formations are exposed only in the core of Laki anticline. The remaining areas show exposures of Tertiary and Quaternary deposits. Pab Formation The term Pab Sandstone was introduced by Vredenburg (1907) and the type section in the Pab Range (lat. 250 31’ 12’’N; long. 700 02’ 58’’E) was designated by Williams (1959). In the core of Laki anticline, it consists of mainly sandstone with minor shale. The thickness of Pab Formation is estimated 100m in the core of Laki anticline. Its lower contact is not exposed in Laki Range, however in Kirthar Range it is contacted with Fort Munro Limestone as transitional and upper contact with Vitakri Formation (red clay and some sandstone) is disconformable. On the vertebrate (dinosaurs, mesoeucrocodiles, etc) found from following Latest Cretaceous Vitakri Formation), the age is being assigned as Late Cretaceous/Late Maestrichtian. Vitakri Formation Malkani (2006c) introduced first time the upper member of Pab Formation as Vitakri member and Malkani (2009a) upgraded this member into Vitakri Formation (Type Vitakri area, lat. 29 0 41’ 19’’N; long. 690 23’ 02’’E) due to its distinct lithology, depositional environments and lateral extension. Vitakri village is about 30 Km in the south-southwest of Barkhan town. Here Vitakri Formation (about 15m thick) consists of red muds with alternated sandstone of fluvial origin. Vitakri Formation of Sulaiman basin is the host of latest Cretaceous dinosaurs and crocodiles. Its lower and upper contact with Pab and Khadro formations are disconfirmable. Ranikot Group The Sangiali Group is here replaced by Ranikot group named by Ranikot (Lat. 250 54’ 24’’N; Long. 670 54’ 38’’ E) including the Khadro, Bara and Lakhra formations. Khadro Formation It was named after Khadro Nai/Nala which is north of Bara Nai but its type section is Bara Nai/Nala Lat. 260 07’ 06’’N; Long. 670 53’ 12’’ E in the northern Laki Range and named by Williams (1959). It includes the Cardita beaumonti beds of Blanford (1878), Venericardia shales of Eames (1952), basal parts of Karkh, Gidar Dhor and Jakker groups, Bad Kachu and Thar formations of HSC (1961). It consists of limestone, sandstone, shale and volcanics. The igneous rocks like Decan trap basalts are found in the Earliest Paleocene Khadro formation in the Kirthar basin exposed in the Kirthar foldbelt and also encountered in the subsurface drill hole. Nusrat Kamal Siddiqui (verbal communication in 1987 with Shah; Shah 2009) named the basalt as Khaskheli basalt. Its lower contact with Vitakri Formation is disconformable and upper contact with Bara Formation is transitional and conformable. Its age is Earliest Paleocene. Bara Formation It was named by Ahmad and Ghani (Written communication in 1971 to Cheema et al. 1977) after Bara Nai (Lat. 260 07’ 06’’N; Long. 670 53’ 12’’ E, Type section) of Laki Range. Its principal 19 reference section is Ranikot (Lat. 250 54’ 24’’N; Long. 670 54’ 38’’ E). It includes the lower Ranikot sandstone of Vredenburg (1906) and lower Ranikot of later workers, Ranikot formation of Williams (1959), Lower Ranikot formation, lower parts of the Karkh, Gidar Dhor and Jakker groups, Bad Kachu, Rottaro and Thar formations of HSC (1961). It consists of soft sandstone, shale and coal. Its lower contact with Khadro and upper contact with Lakhra is transitional and conformable. Its age is Early Paleocene. Lakhra Formation It was named by Ahmad and Ghani (Written communication in 1971 to Cheema et al. 1977) after Lakhra of Laki Range. It includes the upper Ranikot limestone of Vredenburg (1906) and upper Ranikot of lator workers, upper Ranikot formation of HSC (1961). It consists of dominant limestone with minor shale. It is correlated with Dungan Limestone of western Kirthar and Sulaiman basin. Its lower contact with Bara Formation is transitional and upper contact with Sohnar Gaj Formation is disconformable. For fossils pl. see the Dungan Formation in western Kirthar. Its age is Late Paleocene. Laki Group The term Laki group was proposed by HSC (1961) for the Laki Series of Noetling (1903) and lower part of Kirthar Series of Blanford (1876). Laki group includes Sohnari (now upgraded as formation) and Laki formations. It also includes the Tiyon formation of HSC (1961). It is well recognised in the Laki Range and its surroundings. Nuttal (1925) subdivided Laki series in to basal Laki laterite (8m), Meting limestone (45m), Meting shale (30m) and Laki limestone (70-200m). Cheema et al. (1977) proposed two members like Sonhari member (=basal Laki laterite) represents laterite, and Meting limestone and shale member (= Chat member of Nagappa 1959) which include the upper 3 units of Nuttal (1925). Kazmi and Abbasi (2008) mentioned only one formation as Laki Formation. Further Outerbridge et al. (1991) and also others stressed about the two fold divisions of Laki Group. Akhtar et al. (2012) used the Laki Formation for all members/formations of Laki Group may be due to scale problems. So here twofold division of Laki Group is adopted like the lower unit as Sohnai Formation (consists of lateritic clay, ochre, shale, arenaceous limestone, sandstone and coal) and and upper unit as Laki Formation (consists of mainly limestone with minor/subordinate shale). The age of Laki Group is Early Eocene to Middle Eocene. Sohnari Formation It was named by Outerbridge et al (1989) for the basal Laki laterite (8m) of Nuttal (1925) and after the Sonhari member of HSC (1961). Here it is being accepted as formation because other laterites are also named as Dilband Formation (J/K boundary) of Abbas et al (1998), Vitakri Formation (latest Cretaceous to K/T boundary) of Malkani (2009f). It mostly consists of lateritic clay, ochre, shale, yellow arenaceous limestone, sandstone and lignite coal seams. The Sohnai Formation is correlated with Early Eocene Chamalang (Ghazij) Group of western Kirthar and Sulaiman basin, Panoba Group of Kohat sub basin and Nammal Formation of Nammal Group of Potwar sub-basin. Its lower contact with Lakhra Formation and upper contact with Laki Formation is disconformable. Its age is Early Eocene. Laki Formation 20 It was named by Cheema et al. (1977), which is derived from Laki Series of Noetling (1903). It consists of 3 members of Nuttal (1925) like lower member as Meting limestone (45m), middle member as Meting shale (30m) and upper member as Laki limestone (70-200m). The lower and middle members like Meting limestone (45m) and Meting shale (30m) are correlated with the Kirthar Formation of Kirthar Group of western Kirthar. The upper member like Laki Limestone (70200m) is correlated with Gorag (resistant and peak forming limestone) formation of Kirthar Group of western Kirthar. The Kirthar Formation belongs to lower part of Kirthar Group while the Gorag Formation belongs to upper part of Kirthar Group, well exposed in western Kirthar i.e., in the typical Kirthar range and its vicinity areas. Laki Formation consists of mainly limestone with subordinate/minor shale and marl. Its lower contact with Sohnari Formation is disconformable and upper contact with Nari Formation is transitional. The Laki Formation contains foraminifers, gastropods, bivalves, echinoids and algae reported by Noetling (1905), Nuttall (1925), Davies (1926), Haque and Khan (in Lexique 1956), Haque (1962a), HSC (1961) and Iqbal (1973). The foraminifers include Assilina granulose, A. pustulosa, Lockhartia hunti, var. pustulosa, Flosculina globosa, Opertorbitolites douvillei, Fasciolites oblonga, Linderina brugesi and Dictyoconoides vredenburgi, important mollusces include Gisortia murchisoni, Velates perversus, and Blagraveia sindensis and echinoids include Amblypygus subrotundus and Echinolampas nummulitica. These fossils indicate an Early Eocene (Ypresian) age, however it may extends upto middle Eocene. Gaj Group To remove missing link the Gaj group is here being established after the Gaj River in Kirthar Range for the Oligocene Nari and Miocene Gaj formations. Duncan and laden (1884, 1886), Vredenburg (1906b, 1909b), Nuttall (1925, 1926), HSC (1961), Pascoe (1963) Khan M.H. (1968) and Iqbal (1969a) reported foraminifers, corals, mollusks, echinoid, algae and other fossils. The foraminifers include Nummulites intermedius, N. vascus, N. fichteli, N. clypeus, Lepidocyclina (Eulepidina) dilatata, etc., bivalves include Crassatella sulcata, Venus (Ventricola) multilamella, V. (Antigona) peepera, gastropods include Scaphander oligoturritus, Lyria anceps and Tritonsium (Saia) indicum. Pascoe (1936) concluded Stamian of Europe and ranges from Rupelian to Chattian. Khan (1968) assigned Rupelian to early Aquitanian age. HSC (1961) assigned the age of this group as Oligocene to Miocene. Nari Formation It was named by Williams (1959) for the Nari Series by Blanford (1876) after the Nari river. It consists of marine brown sandstone, red, brown and yellow shale, and brown limestone. It is equalent to Chitarwata formation of Sulaiman Basin. Its lower contact with Laki Limestone and upper contact with Gaj Formation is transitional. Fossils details are also mentioned in the above Gaj group. Its stratigraphic position and above mentioned fauna tells Oligocene age. Gaj Formation It was named by Williams (1959) for the Gaj Series by Blanford (1876) after the Gaj river. It consists of estuarine to terrestrial deposits dominantly varicoloured shale with subordinate sandstone, gypsum and limestone. It mostly resembles with Nari formation however the contact is being marked at the end of massive sandstone and at the start of dominant shale lithology. Three beds of gypsum are reported by Alizai et al. (2000) ranging in thickness from 0.33 to 0.93m occurs 21 in Miocene Gaj shales near Johi and Khairpur Nathan Shah areas of Dadu district. It is correlative to Miocene Vihowa Formation of Sulaiman basin. Its lower contact with Nari Formation is conformable and transitional and upper contact with Litra Formation is disconformable. Fossils details are also mentioned in the above Gaj group. Its stratigraphic position and above mentioned fauna tells Miocene age. Manchar Group The term Manchar is derived from Manchar series of Blanford (1876) after the Manchar lake a few kms west of Sehwan. Late Miocene to Pliocene Manchar group represents Litra Formation and Chaudhwan Formation. Manchar group is mostly equalent to upper part of Vihowa Group (Litra and Chaudhwan formations). In Gaj river section it is 2200m thick (Khan et al. 1984) while in Sehwan it is 1000m thick (Pilgrim 1912). Previous worker divided it into lower, middle and upper Manchar. These are exposed in the eastern foot mountains of Kirthar and Laki ranges. Litra Formation The Litra Formation was first used by Hemphill and Kidwai (1973). The type section designated to be Litra Nala (lat. 310 01’N; long. 700 25’E). It consists of dominant sandstone with relative to red to maroon shale and rare conglomerate. The sandstone is grey, thin to thick bedded and massive, fine to coarse grained, gritty and calcareous. The shale is maroon, red, khaki and calcareous. The conglomerate is thin to thick bedded and dominantly sandy and calcareous. Here due to being tail of Indus river, the shale and alternated sandstone was deposited by river system. Its lower contact with Gaj/Laki/Kirthar/Gorag Formation and upper contact with Chaudhwan Formation is disconfirmable and at places angular. This formation is the host of continental vertebrates. Raza et al. (2002) placed the lower age of Litra formation at 11 Ma based on Hipparaion in the lower part of this formation. They also estimated the age of Litra Formation from 11 to 6 Ma i.e. Late Miocene. Khan et al. (1984) dated the lower 1700m of the Formation paleomagnetically as 15.3 Ma to 9-10Ma. Chaudhwan Formation The Chaudhwan Formation was first used by Hemphill and Kidwai (1973). The type section designated to be in Chaudhwan Zam (lat. 310 37’N; long. 700 15’E). It consists of alternated mudstone/shale, sandstone and conglomerate. As a whole shale is dominant in this formation. The mudstone/shale is maroon, khaki and calcareous. The sandstone is grey, brown, thin to thick bedded, fine to coarse grained, gritty and calcareous. The conglomerate is thin to thick bedded and dominantly sandy and calcareous. Thick conglomerate beds with some mud and sands cap the upper part of this formation. These are exposed in the eastern foot mountains of Kirthar and Laki ranges. Its lower contact with Litra Formation is transitional while upper contact with Dada Formation is angular or transitional. This formation is the host of continental vertebrates. According to stratigraphic position, its age may be Pliocene. Sakhi Sarwar Group The term Sakhi Sarwar Group was named by Malkani (2012h) for Pleistocene Dada (mainly conglomerate) and Holocene Sakhi Sarwar (clays, silt, sandstone and conglomerate) formations (Malkani 2012h). These are exposed in the eastern foot mountains of Kirthar and Laki ranges. 22 Dada Formation Its name is derived from Dada River south of Spintangi Railway station (HSC, 1961). It consists of conglomerate with subordinate shale and sandstone. At places it also includes the white and red muds especially in the valley areas. Its lower contact with Chaudhwan Formation and upper contact with Sakhi Sarwar Formation is at places angular or transitional. According to stratigraphic position, its age may be Pleistocene. Sakhi Sarwar Formation It was named by Malkani (2012h) for the varicoloured clays, sandstone, siltstone and conglomerate. Its lower contact with Dada Formation and upper contact with subrecent at places is angular and at places transitional. Its age is Holocene. Subrecent and Recent surficial deposits These are represented by alluvial deposits in the footmountains (Daman) and plain areas deposited by Indus river systems. Thar Desert and some coastal areas consist of eolian sand dune deposits. In the vicinity of high mountan ridges the colluvium scree and talus are also found. STRATIGRAPHY OF INDUS OFFSHORE (GONDWANA FRAGMENT) The offshore areas are significant for petroleum exploration. The Makran offshore areas located in the west of Indus Suture line and show the Balochistan basin stratigraphy and further the trench is also located in the near offshore area. The Indus offshore area located in the east of Indus Suture line and shows the Kirthar basin stratigraphy. ROCKS OF NAGER PARKER IGNEOUS COMPLEX (A GEO-HERITAGE OF INDO-PAK SHIELD) Nager Parker Igneous complex is named by Jan et al. (1997) for acidic and basic igneous rocks. Kazmi and Khan (1973) named as Nagar Igneous Complex, Nagar Parker granite by Shah (1977) and Nagar Parker Massif by Muslim and Akhtar (1995). According to Jan et al. (1997) reported six major magmatic episodes of intrusive and extrusive activities like amphibolites and related dykes, riebeckite-aegirine grey granite, biotite-hornblende pink granite, acid dykes, rhyolite plugs and basic dykes. Nagar Parker Igneous complex is a part of Indo-Pak shield. These rocks may be the extension of Proterozoic granitoids of the Indian Rajasthan. STRATIGRAPHIC CORRELATION OF KIRTHAR BASIN (PART OF GONDWANA) WITH ADJOINING BALOCHISTAN BASIN (PART OF TETHYS), PAKISTAN Kirthar Basin is located in the southern part of Supper Indus Basin which belongs to an IndoPakistan subcontinent (A Gondwana Fragment). The Super Indus Basin is subdivided in to Uppermost/northernmost Indus, upper/north Indus, middle Indus (Sulaiman) and lower/south Indus basins. Balochistan Basin is evolved under Tethys Sea from Cretaceous to recent. Balochistan Basin is subdivided into Chagai-Raskoh-Wazhdad magmatic arc, northern Balochistan/Kakar Khorasan 23 (back arc) and southern Balochistan/Makran (fore arc; arc-trench gap) basins. The Cretaceous strata of Balochistan basin is exposed in Shirin Jogezai area of Qila Saifulla district and also exposed in Chagai and at one place near the Ispikan conglomerate in Makran but these strata not well correlated with Indus basin, however slight resemble with porcelaneous limestone of Parh Group. The Cainozoic of Kirthar Basin is well correlated with adjoining Balochistan basin due to collision of Indo-Pakistan plate with Asian plate during Latest Cretaceous. Due to this terminal Cretaceous collision, the adjoining contact Balochistan Basin occurred with the Indus Basin. Due to this collision the birth of Paleo Indus River systems occurs and ended the dynasty of Paleo Vitakri River systems. The Paleocene Dungan limestone of Indus basin closely resemble with Nisai limestone/Kharan limestone/Wakai limestone of Balochistan Basin. In this way Early Eocene Shagala Group of Balochistan Basin is well correlated with the Chamalang/Ghazij Group (Shaheed Ghat-shale, Toi-sandstone and shale, Kingri-red muds and sandstone-Drug-rubbly limestone and Baska-gypsum and shale) and Kahan Group (Habib Rahi-limestone, Domanda-shale, Pirkoh-marl and shale and Drazinda-shale) of western Kirthar basin and Laki Group of eastern Kirthar (Laki range and adjoining areas). The Murgha Faqirzai Formation (shale, 2000m thick) of Shagala Group is correlated with Shaheed Ghat shale of western Kirthar basin, the Mina Formation (alternation of green shale unit and sandstone unit; 3000m thick) of Balochistan is well correlated with Toi Formation of western Kirthar Basin, and the Shagala Formation (=Shagalu; alternation of terrestrial red shale unit and sandstone unit; 3000m thick) of Balochistan basin is well correlated with the Kingri Formation of western Kirthar Basin and also Sohnai Formation of Laki range and adjoining areas of eastern Kirthar basin. At the hard contact of Indo-Pakistan plate with Asia at the end of Eocene resulted in the form of the Oligocene-Pliocene Vihowa Group (synonyms; Malthanai/Dasht Murgha group) in both basins. The Vihowa Group represents Chitarwata (which is the host of Buzdartherium gulkirao-a baluchithere-the largest land mammals), Vihowa, Litra and Chaudhwan formations. So far last major tectonic episode occurred at Early Pleistocene which deposited the Pleistocene-Holocene Sakhi Sarwar Group (correlate with Boston formation) represents Dada (conglomerate) and Sakhi Sarwar (mud and sandstone with poorly developed conglomerate, while in centre of valleys the mud is dominant) formations well developed in both basins. The southern part of Kakar Khorasan and Makran basins show flysch deposition like Murgha Faqirzai Shale/Hoshab shale and Mina Formation/Panjgur Formation (green shale and sandstone) while the northern part of Kakar-Khorasan basin shows both these formations as flysch deposition while the middle-Late Eocene Shagala (Shaigalu) Formation (sandstone and red to maroon, brown shale and sandstone) as terrestrial/molase deposits which is supported by continental rhinoceros-baluchithere (Pakitherium Shagalai)-the largest land mammalian fauna (Malkani and Mahmood 2016b). CORRELATION OF REVISED STRATIGRAPHIC SET UP (AT GROUP AND FORMATION LEVEL) OF LOWER, MIDDLE AND UPPER INDUS BASINS The Upper (Kohat Potwar) Basin represents Precambrian Salt Range Formation (marl, salt and gypsum), Cambrian Khewra group consists of Khewra (sandstone), Kussak (dolomite, siltstone and sandstone), Jutana (dolomite) and Baghanwala (red shale alternated with flaggy sandstone) and Khisor (thick gypsum in the base and shale in the upper part) formations; Early Permian Nilawahan Group consists of Tobra (Tillitic facies in eastern Salt Range, fresh water facies of siltstone and shale with pollen and spore flora, and a complex facies of diamictite, sandstone and boulder beds 24 increase in westernsalt range and Khisor range), Warcha (speckled sandstone with some shale, Dandot is synonym and lateral facies of Warcha) and Sardhi (greenish grey clay with some sandstone, siltstone and limestone) formations; Late Permian Zaluch Group consists of Amb (sandstone), Wargal (limestone) and Chidru (shale, quartzose sandstone with minor limestone) formations. The Precambrian and Paleozoic rocks may extend into Middle Indus (Sulaiman) and Lower Indus (Kirthar) basins. The Triassic Musakhel Group consists of Mianwali (marl, limestone, sandstone, siltstone and dolomite), Tredian (terrestrial sandstone) and Kingriali (dolomite, limestone, dolomitic limestone, marl, sandstone and shale; Chak Jabbi is synonym and lateral facies of Kingriali) formations. Musakhel Group is correlated with the Khanozai Group of Middle Indus/Sulaiman and Lower Indus/Kirthar basins. Khanozai Group represents Gwal (shale, thin bedded limestone) and Wulgai (shale with medium bedded limestone) formations. The Jurassic Surghar Group comprises of Datta (terrestrial sandstone), Shinawari (shale, limestone) and Samanasuk (Limestone and minor shale) formations. Surghar Group is correlated with the Sulaiman Group of Sulaiman and Kirthar basins. Sulaiman Group represents Spingwar (shale, marl and limestone), Loralai (limestone with minor shale), Chiltan (limestone) and Dilband (ironstone, laterite and brown beds) formations. The Cretaceous Chichali Group represents Chichali (green shale and sandstone), Lumshiwal (cross bedded sandstone and shale of continental origin), Kawagarh (marl and limestone- lateral facies of Lumshiwal Formation in downward slope) and Indus (named by Malkani and Mahmood 2016a as Indus Formation for laterite and bauxite-pisolitic, oolitic, and green chamositic/ glauconitic materials, ironstone, ferruginous and quartzose sandstone and claystone and fire clay) formations. Chichali Group is correlated with the Parh and Fort Munro groups of Sulaiman and Kirthar basins. Parh Group represents Sembar (shale with a sandstone body), Mekhtar (sandstone, commonly called lower Goru, exposed only in Mekhtar and Murgha Kibzai areas of Loralai and Zhob districts), Goru (shale and marl), and Parh (limestone) formations, and Fort Munro Group represents Mughal Kot (shale/mudstone, sandstone, marl and limestone), Fort Munro (limestone), Pab (sandstone with subordinate shale) and Vitakri (red muds and greyish white sandstone) formations. The Paleocene Hangu Group (named by Malkani and Mahmood 2016b) consists of Hangu (synonym Patala; shale, sandstone and coal) and Lockhart (relatively fine nodular limestone as compared to Sakesar limestone) formations. Hangu Group is correlated with the Sangiali Group of Sulaiman basin and western Kirthar basin and Ranikot Group of eastern Kirthar basin. The western Kirthar basin belongs to Kirthar range and westward upto western Indus Suture. Western Indus suture (WIS) is a suture between the Indus and Balochistan basins. The eastern Kirthar basin belongs to Laki range and eastward upto Nagar Parker Igneous complex. Sangiali Group represents Sangiali (limestone, glauconitic sandstone and shale), Rakhi Gaj (Girdu member, glauconitic and hematitic sandstone; Bawata member, alternation of shale and sandstone), and Dungan (limestone and shale) formations. Ranikot Group represents Khadro (limestone, shale, sandstone and volcanics), Bara (soft sandstone, shale and coal) and Lakhra (limestone with subordinate shale) formations. The Early Eocene Nammal Group (named by Malkani and Mahmood 2016b) of Potwar sub-basin and eastern Kohat sub-basin consists of Nammal (green shale and muds) and Sakesar (coarse nodular/rubbly limestone) formations. Nammal Group is correlated with the Panoba Group of Kohat sub-basin, Chamalang/Ghazij Group of Sulaiman basin and also western Kirthar basin and Sohnari Formation of Laki Group of eastern Kirthar basin. The Panoba Group (named by Malkani and Mahmood 2016b) of western Kohat sub-basin represents Panoba (shale; equivalent to Shaheed Ghat shale of 25 Sulaiman basin), Chashmai (green shale and sandstone; equivalent to Toi Formation of Sulaiman basin), Gurguri (brown shale and sandstone; equivalent to Kingri Formation of Sulaiman basin), Shekhan (limestone, shale; equivalent to Drug rubbly limestone of Sulaiman basin), Bahadurkhel salt and Jatta gypsum. Actually in the western Kohat the stratigraphy of Sulaiman basin is extending. So the terms of Chamalang/Ghazij and Kahan groups should be used in the western Kohat sub-basin. Chamalang (Ghazij) Group represents Shaheed Ghat (shale), Toi (sandstone, shale, rubbly limestone and coal), Kingri (red shale/mud, grey and white sandstone), Drug (rubbly limestone, marl and shale), and Baska (gypsum beds and shale) formations. Laki Group represents Sohnari (lateritic clay and shale, yellow arenaceous limestone pockets, ochre and lignitic coal seams) and Laki (limestone with subordiante shale) formations. The Early-Middle Eocene Kuldana Group (named by Malkani and Mahmood 2016b) consists of Chorgali (shale and limestone and dolomite) and Kuldana (shale and marl with minor sandstone, limestone, conglomerate and bleached dolomite) formations. Kuldana Group is correlated with the Kahan Group of Sulaiman basin and western Kohat sub-basin and Kirthar Group of western Kirthar basin and Laki Formation (mainly limestone with subordinate shale) of Laki Group of Laki Range and vicinity areas of eastern Kirthar basin. Kahan Group represents Habib Rahi (limestone, marl and shale), Domanda (shale with one bed of gypsum), Pir Koh (limestone, marl and shale) and Drazinda (shale with subordinate marl) formations. The Early to Middle Eocene Kahan Group consists of Habib Rahi (limestone, marl and shale), Domanda (shale), Pirkoh (white marl, limestone and shale) and Drazinda (shale) formations, this group is well exposed in Sulaiman basin and Kohat sub-basin. Kirthar Group represents Kirthar (limestone, marl and shale) and Gorag (resistant and peak forming limestone with negligible shale and marl in western Kirthar; limestone with negligible shale and marl in eastern Kirthar) formations. The Miocene-Pliocene Potwar Group (=Siwalik Group) was named by Malkani and Mahmood 2016b) include the Chinji (red and maroon muds), Nagri (sandstone) and Dhok Pathan (alternation of sandstone and red/maroon/brown muds) formations. The Potwar Group is correlated with the middle and upper part of Vihowa group (except Oligocene Chitarwata Formation) of Sulaiman basin, Gaj Formation of Gaj Group and whole Manchar Group (Litra and Chaudhwan formations) of Kirthar basin and Murree Formation of northern Potwar (Murree and surrounding areas and Kala Chita Range) and southern Azad Kashmir (Muzaffarabad-Kotli-Mirpur). Kamlial formation is included in the upper part of Murree formation (alternating sandstone and red/maroon mud units). OligocenePliocene Vihowa Group represents Chitarwata (grey ferruginous sandstone, conglomerate and mud), Vihowa (red ferruginous shale/mud, sandstone and conglomerate), Litra (greenish grey sandstone with subordinate conglomerate and mud), and Chaudhwan (mud, conglomerate and sandstone) formations. The Oligocene terrestrial Chitarwata Formation of Sulaiman basin is correlated with the marine Nari formation of Gaj Group. The terrestrial Vihowa Formation of Sulaiman basin is correlated with the marine estuarine and subkha type supratidal evaporitic Miocene Gaj Formation of Gaj Group. The Oligocene-Miocene Gaj Group consists of Oligocene Nari (sandstone, shale, limestone) and Miocene Gaj (shale with subordinate gypsum, sandstone and limestone) formations. Late Miocene-Pliocene Manchar Group represents Late Miocene Litra (greenish grey sandstone with subordinate conglomerate and mud), and Pliocene Chaudhwan (mud, sandstone, conglomerate) formations. The Pleistocene-Holocene Soan Group (named by Malkani and Mahmood 2016b) for the Pleistocene coarse clastic Lei (Mirpur/Kakra) Conglomerate (massive conglomerate) and then Holocene mixed fine and coarse clastic of Soan Formation. Soan Group consists of coarse clastic with relative to Potwar Group. Soan Group is correlated with the Sakhi Sarwar Group of Sulaiman 26 and Kirthar basins. Sakhi Sarwar Group represents Dada (well developed conglomerate with subordinate mud and sandstone) and Sakhi Sarwar (poorly developed conglomerate with subordinate mud and sandstone, while in centre of valleys the mud is dominant) formations (Malkani 2012, Malkani et al. 2017a,b,c,d). Further correlation at formation level can be seen in Fig.1. MINERAL RESOURCES OF KIRTHAR BASIN (LOWER INDUS BASIN), PAKISTAN The Kirthar Basin under the territory of Balochistan Province includes mineral commodities like Coal, Iron, Fluorite, Sulphur, Building stones, Decorative stones, Marble, Celestite, etc. Mineral Potential of Kirthar Basin/Lower Indus Basin/Southern Indus Basin under the territory of Balochistan Province is being described as below (for detail please see the Malkani 2011a): MINERAL RESOURCES OF WESTERN INDUS SUTURE (WIS; SUTURE BETWEEN INDUS AND BALOCHISTAN BASINS), BALOCHISTAN PROVINCE Western Indus Suture consists of ophiolitic, igneous and associated and faulted sedimentary and metamorphic rocks. So ophiolite related minerals like chromite, asbestos, magnesite, manganese, iron, barite, fluorite, etc are found. For detail please see the Malkani (2011a), Malkani and Mahmood (2016a), Malkani et al. (2016) and Malkani et al. (2017) paper/report on Balochistan province and Pakistan. MINERAL RESOURCES OF WESTERN KIRTHAR BASIN (KIRTHAR RANGE AND SURROUNDINGS), BALOCHISTAN PROVINCE The Western Kirthar Basin under the territory of Balochistan Province includes mineral commodities like Coal, Iron, Fluorite, Sulphur, Building stones, Decorative stones, Marble, Celestite, etc. These are briefly described as: Coal The Eocene coal is reported from Johan (Kalat District) and Abe Gul (Mastung District) areas, Paleocene coal from Dureji (Khuzdar-Bela region), Khauri (Khuzdar District) and Rodangi (Kalat District) areas. The coal of Johan is quite extensive and lenticular, minings were tried many times but not continued due to thin and discontinuous exposure and security reason. The coal of Abe Gul (Mastung District is found in Toi Formation on high peak and has very small extension. Further Malkani and Tariq (1992) reported Paleocene coal in Radangi Formation (limestone with subordinate shale) of western Shirinab valleyof Kalat district. The Rodangi area shows upto 1 m thick carbonaceous shale with lenticular nature. Mining was tried but no any successful coal seam was found (Malkani and Tariq 1992). Kazmi and Abass (2001) reported the coal from Dureji in the southern Kirthar Foldbelt but details are not provided so far. Malkani (2010f) reported first time the coal of Khauri locality of Zidi area (Khuzdar District) and here the coal and carbonaceous shale is about 1 foot thick seam found in the the Tertiary limestone, marl and shale. It is exposed near the road cut of Khuzdar to Karkh road. Iron Ore 27 Dilband iron ore found at J/K boundary in the Vicinity of Dilband and Johan area of Mastung, Kalat, and Bolan and Quetta districts, It is found between the Jurassic Chiltan limestone and Sembar Formation. It mostly represents and overlaps the Sembar Formation. Abbas et al 1998 has named it as Dilband Formation. Pakistan has large iron deposits occurring as ironstone and lateritic beds showing disconformities like Kirthar (lower Indus) foldbelt (Dilband). It is recently discovered by GSP with considerable economic significance. It is located on the Dilband area just NE of Johan Village. It is 70km from National Highway and 100km from Kolpur railway station. The ore is found as J/K boundary with low to gentle dips. The iron horizon is 1-7m thick with an average value of 2m. Mineralogically it consists of hematite with calcite, quartz and chlorite. It contains 35-48% iron. The estimated reserves are 200mt. Due its large tonnage, low and gentle dips, favorable location (also close to Mach and Bibi Nani with belt loading), open cast mining, simple mineralogy and acceptable grade, it is considered better than other ores in Pakistan (Abbas et al, 1998). It comprises ironstone ore which is being mined in Europe, North America, Russia and China. The Pakistan Steel Mills have successfully blended 10% of raw Dilband ore with improved iron ores to produce sinter and pig iron. Laboratory scale experiments indicate that this ratio can be raised to 15% and possibly upto 70% after beneficiation. Chemical analyses of iron ore represents Fe 45.7-48.03%, FeO 2.30-2.95%, SiO2 13.7- 14.6%, CaO 2.23-2.4%, MgO 1.6-2.2%, MnO 0.09-0.11%, Al2O3 5.30-6.04%, TiO2 20.32-0.35%, P 0.24-0.34%, Cu 0.01-0.012%, S 0.12-0.19%, Zn 0.07%, Loi 4.5-7.45%. Pakistan Steel mill is started to use the iron of Dilband area but due to security it was abandoned. So necessary security arrangement may be provided to develop the Dilband iron ore for Pakistan Steel and to save the export fundings. In this impmkill In Sindh lateritric clay and ochre, pockets of limonite and ochre are found in Eocene Sohnari Formation at Lakhra, Meting and Makli hills (Abbass et al., 1998). Witherite It is a barium carbonate with 4.3 specific gravity. It occurs as gange minerals with galena and barite. It is a source of barium salts and also used for pottery industry. Due to high specific gravity, it can be used for drilling industry. A deposit of witherite has recently been discovered a few kilometers west of Deghari in Balochistan. It occurs in veins and lenses in the Jurassic Chiltan limestone and mineralization extends for about 1 km (Sispal Kella, verbal communication with Kazmi and Abbas, 2001). Fluorite The attraction of mineral specimen as distinct from a facetted stone lies in its form and colour. Mineral specimens do not have to be of gem quality, though the gem crystals that escape cutting are admittedly most beautiful. In recent years a large and a flourishing market for good mineral specimen as collector’s items has developed world wide. Attractive violet fluorite crystals occur in the Koh-Dilband (290 30’N; 660 55’E) fluorite mines in Kalat Division. In the vicinity of Dilband, the fluorite is reported from Pad Maran, Chah Bali and Dobranzel (Isplinji) areas (Bakr, 1965a; Mohsin and Sarwar, 1980). Fluorite occurs in veins and fractures in the Jurassic Chiltan/Zidi limestone. The calcite, quartz, barite, etc are the gangue minerals in fluorite veins. Abbas et al. (1980) estimated 0.1 million tons of fluorite deposit of Dilband-Maran-Phad Maran, District Kalat. Malkani (2010a) discovered the second largest deposits of fluorite in Pakistan from Loalai District and surrounding areas in Jurassic Loralai Limestone. New fluorite deposits have been 28 discovered by Malkani (2010a,2011,2012a) from the Jurassic Loralai limestone of Gadebar, Daman Ghar, tor Thana, Wategam, Mekhtar, Balao, Mahiwal areas of Loralai District, Balochistan Province (Fig.1a,d). The first largest deposit of fluorite (over 0.1million ton) from Pakistan are located in Dilband and in its vicinity in Kirthar foldbelt (Bakr 1962, 1965; Mohsin and Sarwar 1974; Abbas et al., 1980). New fluorite deposits from Loralai regions are the second largest deposits of Pakistan (Malkani 2010a, 2011, 2012a). The fluorite of Loralai area occurs as veins and as disseminated grains in fractures and faults which are found in limestone of Loralai Formation of Jurassic age forming anticlinal core. Fluorite has many colors such as light-yellow, pink, light-grey, blue and green. Chemical analysis shows CaF2 varies from 95.20-95.40%, CaCO3 from 3.20-3.40% and SiO2 from 1.40-1.44%. Average weight % concentration of Ca is 49%, F is 45%, SiO2 is 2.30%, CuO is 0.5%, Al2O3 is 2%, Fe2O3 is 0.08% and LOI is 1.47%. This type of fluorite can be used for acid preparation and also as gemstones. The mining is started in Zarah, Tor Thana and Mekhtar (Balao, Sande, Inde and Zhizhghi) areas. Here the reserves estimated are 50000 tons. Attractive gem quality fluorite crystals are found in light-green, yellow and light-blue colors from Mekhtar, Wategam Zarah of Loralai district. The significant area for fluorite exploration is the Jurassic strata of Sulaiman and Kirthar fold belts and Western Indus Suture (WIS) (Malkani 2010a,2011,2012a). The third largest deposit of fluorite from Pakistan has been discovered by Malkani (2002,2004c) and Malkani et al. (2007) from Jurassic Chiltan Limestone of Mula-Zahri Range, Kirthar foldbelt. Malkani (2002; 2004d) reported 6750 tons of fluorite. Malkani et al. (2007) reported 20,000 tons of fluorite deposit. The main fluorite localities are Koath, Mardan-Jhakkur-Korangani and adjoining areas of Moola Zahri Range of western Kirthar Basin. Mula Zahri range is located 85 km northeast of Khuzdar town. The base area is accessibile from Khuzdar via mototable track. The Koath locality is found in the southern part of fluorite bearing Range and Mardan-JhakkurKorangani localities are found in the northern part of fluorite bearing range. Many other localities in the Mula Zahri range host the fluorite. The fluorite ore areas are on the peak of range which can be accessed only by footwalk climbing of many hours to two days. The Koath fluorite locality is two hour climbing from Lakha Pir (the base area on Mula river bank). The Mardan-Jhakkur-Korangani localities need two days climbing from east and one day climbing from west. The relief of Mula Zahri range varies from 500m to 2280m. Mula Zahri range is a major anticlinorium trending north south. The core formation is Jurassic Chiltan/Zidi limestone which is also host of fluorite. Fluorite is found on and around the hinge line of anticlinorium. Fluorite (CaF2) is the fluxing materials used in preparation of steel. It used for preparation of HF acid and elemental fluorine. It is being used as jewelry and gemstones. It is also used for the manufacturing of white and cloured opalescent glass, paints, as binder for abrasive wheels and carbon electrodes, in pigments, and enameling of cooking utencils. The colour of fluorite is light green to deep green, bluish grey to pinkish grey, and rarely brown to pinkish brown. The intensity of bluish grey and dark green fluorite is increasing toward north. It is transparent to opaque and massive to perfect crystals. So fluorite deposits are in high demands in Pakistan. Mula Zahri fluorite deposits are the third largest deposits of fluorite in Pakistan after the first Dilband and second Loralai deposits. The fluorite occurs in veins and fracture fillings showing clearly formed by hydrothermal activities. The individual vein varies in width from few centimeters to half meter and length varies from 10 to 50m. The chemical analyses show CaF2 content varies from 95.20 to 96.50%. The ore contains about 60% fluorite. The gangue mineral of fluorite ore is calcite. No detailed exploratory work is done, however the estimated deposts of fluorite from Koath and Mardan-Jhakkur-Korangani is about 20,000 tons (upto 50 m easy mineable 29 depth). The other localities of fluorite from Mula Zahri Range are Kil, Chinoka, Bhai Jov, Patham, Hanjiri, Bilawal, Zardak, etc. Further the other areas having best exposures of Chiltan limestones like Saplao, Siah Koh, Patk, Gazg, Nagau, etc areas are significant for further exploration of fluorite and also overlying iron of Dilband Formation. Further exploration in Jurassic Chiltan/Zidi limestone of Kirthar basin, Chiltan/Takatu and Loralai limestones of Sulaiman basin and Samanasuk limestones of Kohat-Potwar basin are promising for exploration of fluorite, trackways of reptiles (dinosaurs, pterosaurs, crocodiles, etc) and birds, and petroleum. Celestite The celestite nodules are commonly found in Eocene Kirthar (limestone shale) and Gorag (mainly resistant peak forming limestone) formations of Kirthar Group of Karkh area (Malkani, 2010a;2012; Malkani and Mahmood 2016b). The Kirthar foldbelt have wide exposures of Eocene Kirthar and Gorag formations of Kirthar Group. As the Kirthar Group is correlative to upper Laki limestone and also Tiyon limestone which are also the host of Thano Bula Khan celestite deposits. Sulphur Sanni (south of Dhadhar) and Koh-i-Sultan (near Nokkundi) in Balochistan is the main sulphur localities. Sanni deposit is located in the foothills of Kirthar Range in the south of Dhadhar town. The Sanni deposit (280 02’N; 670 27’E) is about 20km to the SW of Sanni Village. It is 60km west of Bellpat railway station and reached from there by a dirt road which passes through Bagh and Shoran. The mine was active to the prior to the visit of C. Massn in 1943. In 1888 the mine caught fire and collapsed. The shortage of sulphur early in World War II promoted the Geological Survey of India to reopen the mine. Seven audits were started and works abandoned at 1942 due to caving ground and poor ventilations. Three beds of sulphur totaling 20feet in thickness and containing from 32-68% sulphur were described by Krishnaswamy in 1941. Each bed is separated by 15feet of sandstone. Cotter (1919) estimated an ore bed 11 feet thick and 1700,000 square feet in area and calculated 36,000 tons of ore allowing 25% for mining losses. An estimate (HSC, 1961) of 18,000 tons of reserves was based on an assumed extent of ore 200 feet from the face of the hill having thicknes of 10 feet. The ore is controlled by competence of beds. The sulphur is confined to porous and breecciated zones, joints and bedding planes in soft argillaceous sandstone. The tar or martha was noted in the lower working representing a genetic association of petroleum and sulphur. The hydrogen sulphide gas migrated and deposited by oxygen bearing water precipitated sulphur. The gypsum bearing Eocene limestone probably underlies the area. A gypsum layer 3-4feet thick overlies the sulphur formation at Sanni. Sulphur occurs as veins or as replacement of sandstone matrix in the Nari Formation. The ore contains 45% sulphur and the reserves are estimated at about 58,000 tons (Muslim, 1973a). Following minor showings of sulphur are also reported. Laki Sulphur deposit (260 16’N; 670 57’E) was described by Vicary (1847) around the vicinity of hot spring near the town of Laki (Nagell, 1965). Gokurt sulphur deposit (290 33’N; 670 28’E) was reported by Tipper (1909) in the Bolan Pass in massive limestone of Late Cretaceous age. HSC (1961) shows the deposits in the Eocene limestone. It is 50km north of Sunni sulphur deposit. Buildings, Construction and Decorative Stones Large reserves of recrystallised limestone and marble occur widely in the western Kirthar range and now it is being used from the near road Kirthar range. Marble or Zidi limestone (Chiltan limestone) 30 deposits are found in Goru and other areas of Mula Zahri range, Khuzdar district. Further Paleocene Dungan limestone of Karkh, Mandhre Jove (best deposit) and Moola-Zahri (Mula Zahri) ranges, Khuzdar District, Balochistan. Several varieties of fossiliferous limestone of Jurassic to Eocene sequences in various parts of western Kirthar are being mined and marketed under different names. During 1997-98 about 344,000 tonnes of marble was produced. The private sector exclusively deals with the production, processing and marketing of marble and other decorative stones. Gemstone and Jewelry Resources Gemstones and jewelry resources are growing rapidly in Balochistan. Gemstones and jewelry resources like jasper, chert, flint, onyx, fluorite, etc production is growing rapidly in Balochistan. Thick jasper, chert beds upto 1 meter thick and beautiful calcite veins upto 1 m thick are found in Jurassic limestone of the southern part of western range of Khad Kucha valley, District Mastung and also found in Goru and Parh limestone in Western Indus suture and also Khuzdar areas. The chert, flint, Jasper, etc are found in the conglomerate, gritstone, conglomeratic sandstone of OligoceneHolocene detritial rocks. Others Phosphate from Pabni Dhora to Shah (Lasbela area) (Kazmi and Abbas, 2001) and celestite in Eocene Kirthar and Gorag formations of Kirthar Group of Karkh area (Malkani, 2010) have been reported. The Kirthar foldbelt have some valleys and plain areas inside, suitable for dam construction, and also fore deep (Daman) of Kirthar foldbet which have much barren areas, indicate for urgent dams construction. The Dams on Mula and Gaj Nalas are urgent demand due to population increase and also having barren areas for water utilization. Ahmad (1962) reported the bituminous residues known as Salajeet were found in some parts of the Pab Sandstone in the Khuzdar region MINERAL RESOURCES OF EASTERN KIRTHAR BASIN (LAKI RANGE AND SURROUNDINGS), SINDH PROVINCE The Kirthar basin consists of Kirthar fold belt in the west and Sindh plain in the east. The eastern part of Kirthar fold belt is situated under the Territory of Sindh Province and western part is situated under the territory of Balochistan Province. The Sindh plain is located under the territory of Sindh Province. Mineral Potential of Kirthar Basin/Lower Indus Basin/Southern Indus Basin under the territory of Sindh provinces is being described as below: Metallic and Non-Metallic Mineral Resources Abrasives Abrasive type red ochre is found in Eocene Sohnari beds, nodular flints between Rohri and Kot diji; in west of Jhol Dhaund, around Harmon Mohatta coal mine west of Sohnari Dhand (west of Jhimpir), west of Ongar Jhol Dhand (north of Thatta) and Sohnari 15km east of Jhimpir; Grity Pab sandstone of Khadro and Bara areas (can be used for abrasive purposes); Quartz deposits of Cretaceous Pab Formation from eastern slope of Lakhi range district Dadu (Ahmad 1969). 31 Alum, Trona (Source of Na) and Potash Salts Alum, Trona (source of Na) and potash salts associated with rock salt deposits and lakes are found in the vicinity of Sindh coastal areas (Malkani and Mahmood 2016a). Alum from pyritiferous shales of Gajbeds from Maki Nai, shales of Ranikot group and Nari/Gaj group and at Shah Hassan near Trimi (Heron 1954). Celestite The Thano Bula Khan celestite deposits occur as celestite-calcite veins along a major fault in the Eocene Laki Formation in the northern vicinity of Thano Bula Khan. The ore contains 98.75% SrSo 4 and the reserves are 320,000 tones (Moosvi 1973). Gypsum Gypsum has multi-uses like soil conditioning, cement resources, construction materials, etc. Alizai et al. (2000) reported 10.4mt gypsum in three beds ranging in thickness from 0.33 to 0.93m occurs in Oligocene-Miocene Gaj shales near Johi and Khairpur Nathan Shah areas of Dadu district. Gypsum upto 1m thick are found at many places in Thar Desert. Heavy Mineral Concentrates Tungston/sheelite, gold and other heavy mineral concentrates (magnetite, ilmenite, garnet, epidote, zircon, tourmaline, amphibole/hornblende and tremolite, apatite, pyroxene, etc) from placer in the Indus River and molase rocks like Vihowa group, Manchar group and recent sea; Zircon from the shore areas, gold (can be explored) from Nagar Parker and Indus placer. Iron Ore Iron, laterite and ochre reported from Lakhra, Meting and Makli hills, Nagar Parker, Jhal Dhand, Sohnari Dhand, and Noriabad (Ahsan 2006); Nari Formation and in Manchar/Vihowa group in the eastern Kirthar foldbelt; in Sindh lateritic clay and ochre, pockets of limonite and ochre are found in Eocene Sohnari Formation at Lakhra, Meting and Makli hills (Kazmi and Abbas 2001). Pyrite Pyrite is found as disseminated in carbonaceous shale and coal strata at different places. Gemstone and Jewelry Resources Gemstones like agate and chalcedony from Nagar Parker, chert, flint and Jasper from Vihowa group/Manchar group especially from the conglomerate, gritstone, conglomeratic sandstone of Manchar/Vihowa group of eastern Kirthar and Lakhi range and other areas. So far flint stone is being produced from Sindh. Agromineral Resources These may be found in Mesozoic and Cenozoic sediments of Kirthar fold belt regions. Cement Raw Material Resources 32 Cement raw materials like limestones and shales of different age are found as large quantity in Sind Province while gypsum deposits are very small and limited. However very large/ huge deposits of gypsum (Malkani 2010a,2011a; Malkani and Mahmood 2016a) are found in Sulaiman Foldbelt which is located just north of Sindh Province. Ceramic Mineral Resources Clays/shales are used in earthenware works, brick making, mud houses, etc. Practically clays depend upon physical properties and specific test must be made for specific requirements. Chemical analyses have little value for the quality and its use. Ball clay is being produced from Sindh. Various types of Clay deposits are found in Chamalang/Ghazij, Kahan, Kirthar and Vihowa/Manchar groups. Ceramic Mineral Resources/clays found from Laki, Kirthar and Vihowa/Manchar groups; China clay from Nagar Parkar and Islamkot Thar, Dhed Vero, Parodhoro, Karkhi, Dungri, Motijo, Vandio, Ramji-jo-Vandio, and Didwa-Surachand areas; China clays from Nagar Parker area; fuller’s earth from Thano Bulla Khan (Dadu district) and Shadi Shahid (Khairpur; near Jheruk and Rohri and at Begamji; fire clay from Dadu district, Sohnari Dhand/Jhimpir; Laki group, Ranikot group and Vihowa/Manchar group of eastern Kirthar Foldbelt; China Clay It is formed due to alteration of feldspars. It is used in the manufacture of tablewares, sanitary fittings, tiles and electric insulators, paper filling and special type of cement. GSP has discovered and studied in detail the Shah Dheri, Nagar Parkar and Islamkot deposits (Moosvi et al., 1974; Kella, 1983; Griffith, 1987; Jafry undated). In Nagar Parker it occurs as several large pockets which occur in a plain area at shallow depths a few cm to 2m depth. The deposits are largely covered by a thin cover of soil. Deposits occur at Dhed Vero, Parodhoro, Karkhi, Dungri, Motijo, Vandio, Ramji-joVandio, and Didwa-Surachand area. Laboratory studies have shown that the alteration of feldspar into kaolinite is complete. It is coarse grained and 31-40% particle are below 3 microns and 12.3 to 19.1% below 2 microns. X-Ray analysis shows that the Kaolinite and quartz are the major constituents with some gypsum, calcite, and dolomite, with traces of zircon, rutile, hematite and amphiboles. Different thermal analyses show a large exothermic peak between 970 0 C and 9900 further confirming that kaolinite is the major constituents. The measured reserves are 3.6mt (Kella, 1983). The Nagar clay contains upto 2.56% CaO, which is however reduced to1.31% on washing. The raw and washed chemical composition of Nagar Parker China Clay deposit show SiO 2 66.46%, 46.06%; Fe2 O3 0.38%, 0.85%; TiO2 0.86%, not analyzed; Al2 O3 21.57%, 35.70%; CaO 2.56%, 1.31%; MgO 0.34%, 0.34%; Na2 O 0.05%, 0.15%; K20 0.21%, 0.21%, and loss on ignition 14.23% respectively (Griffith, 1987). Beneficiation studies show that the Nagar clay separates easily from quartz, calcite, dolomite, gypsum, etc by simple washing and there is high recovery of kaolinite 8895% when sieved through 240 mesh. Drilling for evaluation of Thar coal has revealed large deposits of China clay in Islamkot area. The clay occurs in beds 0.4m to 7.1m thick, overlying and underlying the coal beds. The clay has been encountered at depth 133 to 201m. The estimated reserves are 20mt in Islamkot area (Jafry, undated; Kazmi and Abbas 2001). Smaller deposits found from Dir, Hazara and Gilgit also. So far China clay is being produced from KPK and Sindh. Fire Clay 33 It is resistant to shrinkage, abrasion and corrosion under high temperature and withstands thermal spalling. It is very low in iron oxide content <2% and high in alumina (24-45%). It is mostly associated with the coal bearing strata. It is also found from Dadu district. These are residual sedimentary deposits generally found at the base of Eocene Sohnari Formation of Laki group from Sindh. Fuller’s Earth/ Bentonite It was formerly used for fulling or cleaning woolen fabrics and cloth, its absorbent properties causing it to remove greasy and oily matters. Its modern use is reefing of oil and fats. It is nonplastic, greenish grey, bluish grey and greenish brown clay with soapy feel. It is use for fulling valued for its decolorizing and purifying properties. The Khairpur deposits show SiO2 49.6%, 46.20%; Fe2 O3 6.66%, 8.76%; Al2 O3 11.94%, 22.86%; CaO 9.12%, 2.43%; MgO 3.13%, 1.94%; Na2 O 0.25%, 1.25%; K20 1.94%, 2.62%; and loss on ignition 16.18% and 12.65% respectively (Ahmad et al., 1987). In Sindh the Thano Bulla Khan (Dadu district) and Shadi Shahid (Khairpur) is main producer. Fuller’s earth is formed in the flood plains of Tertiary river channels which also deposited coal in Pakistan. In recent years it is being utilized in oil refining and other industries in the country. With activation this clay may be used in vegetable oil and ghee industries. It is also being used in insecticide, foundries and steel industries. Its demands are being increased. It is being produced from Punjab, Sindh and KPK. Silica Sand It is used as an abrasive, for the manufacture of glass and some chemicals. It is used in refractory, in sinter and allied complexes of steel mills and has metallurgical applications. Quartzose sand free of impurities is used as silica sand or glass sand. Silica sand is found from Meting to Jhimpir railway stations and in Eocene and Oligocene strata near Thano Bula Khan in Dadu district and Jangshahi deposits. Large deposits of silica sands are found in the Eocene and Oligocene strata near Thano Bula Khan in Dadu district. Pakistan steel alone used 80,000 tons annually from Thano Bula Khan. The demand of silica sand is likely to increase in the production of iron and steel and with expansion of glass and other user industries (Kazmi and Ahmad 2001). Construction, Dinension and Decorative Stone Resources Large reserves of limestone/marble occur widely in the Kirthar and Laki ranges and now it is being used from the near road Kirthar range. Several varieties of fossiliferous limestone of Paleocene to Eocene sequences in various parts of Sindh are being mined and marketed under different names. During 1097-98 about 344,000 tones of marble was produced. The private sector exclusively deals with the production, processing and marketing of marble and other decorative stones. large Construction stone, dolomite and Industrial rocks Resources from Jurassic to Eocene sequences in Kirthar and Lakhi ranges, Thar and Cholistan desert; different type of granites and other Igneous along with some metamorphic rocks from Nagar Parker, Coal Resources-Promising Subsurface Extension Pakistan is ranked 7th internationally regarding lignitic coal reserves but unluckily importing coal. Due to energy crises and increasing population it is vital to discover new coalfields in order to meet requirements. Coal deposits are extensively developed in all the four provinces of Pakistan and also 34 Azad Kashmir. Coal from different areas of Pakistan generally ranges from lignite to high volatile bituminous. These coals are friable, with relatively high content of ash and sulphur. As a result of research by Malkani in 2012 the total coal reserves of Pakistan are increased upto 186,282.43 million tones/mt due to some extensions of previous coalfields and also many new coalfields of Balochistan. Due to recent research by Malkani and Mahmood in early 2016 the total coal reserves of Pakistan increased upto 186,288.05mt with break up as Sind 185457mt, Balochistan 458.72mt, Punjab 235mt, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 126.74mt and Azad Kashmir 10.59 mt. Pakistan has huge coal reserves of 186,288.05 mt. Out of which 3479.86mt are proved, 12023.93mt are indicated, 56951.96mt are inferred and 113832.30mt are hypothetical. The bulk of coal reserves are found more than 99% in Sind Province and more than 94% in Thar coalfields of Sind. In Sind it occurs in Sonda-Thatta (3700mt), Lakhra (1328mt), Indus East (1777mt), Badin (850mt), Meting-Jhimpir (161mt), Jheruck (1823mt) Ongar (312mt) and Thar (175506mt, which is one of the largest coalfields in the world). The summary of coal quality and quantity are shown in Table 1. Thar Coalfields Thar coalfield is among the largest coalfields of world. Thar Coalfields host 175,506mt which puts Pakistan amongst the 7th largest lignite deposits of world. This coalfield is spread over 9000 km2 with 140km N-S and 65km E-W extension (40L/1, 2, 5, 6). About 410km metalled road upto Mithi from Karachi via Hyderabad-Mirpurkhas-Naukot and also via Thatta-Badin-Naukot to Mithi is available. From Mithi to the coalfield, sandy track is covered by 4*4 vehicles. The area is semi arid with low rainfall. The coalfield rests on Pre-Cambrian shield rocks and is covered by sand dunes. The coal thickness varies from 0.20-22.81m. There are maximum 20 coal seams. The most common depth is 150-203m. The overburden varies from 114-245m above the top coal seam. The claystone is the roof and floor rock. There are 4 blocks. The reserves of Block-I show 3566mt with detail as 620mt measured, 1918mt indicated and 1028 inferred. Block-II shows 1584mt with 640mt measured and 944mt indicated whereas Block-III shows 2006mt with 411mt measured, 1337mt indicated and 258mt inferred reserves. Finally, Block-IV shows 2559 mt with 637mt measured, 1640mt indicated and 282mt inferred reserves with rest of Thar coalfield showing 165,791mt with a detail of 392mt measured, 3556mt indicated and 49138mt inferred reserves. The grand total of Thar coalfield reserves is 175,506mt with 2700mt measured, 9395mt indicated, 50706 inferred, 112,705mt hypothetical reserves. The coal is formed from herbaceous plants (reed), does not reveal a warm climate in the past and also indicate little fluctuation in water-table. The low ash and low sulphur show raised peat bogs and acidic environments. The marine fossils interfingerings with terrestrial coal show transgression and regressions of sea. The drainage pattern was smaller and delta was reworked by waves to produce barriers for broad peat blankets. The thick coal seam with low ash and sulphur indicate stable upper delta environments (Ghaznavi, 2002). Lakhra Coalfield Coal from Lakhra Sindh is found in 1853 by Baloch Nomads. Lakhra Coalfields (Dadu district) shows 1.3bt of coal discovered by GSP. The coal is found in the Paleocene Bara Formation. The environment is marine, lacustrine, estuarine, deltaic and lagoonal deposits containing plant fossils and carbonaceous beds at several horizons (Ghaznavi, 2002). The coal is found in the gentle Lakhra anticline. All the coal is found in shallow depth 50 to 150m. The beds are faulted with 1.5-9m dislocation. A large number of coal seams are encountered in drill hole but only 3 coal seams namely 35 Dhanwari, Lalian and Kath are significant. The Lailan seam has persistent thickness (0.75-2.5m with aver. 1.5m) for mining. About 369 drill holes have been drilled so far. This coal has high contents of ash and sulphur. Most of the sulphur is pyritic (70%) whereas 25% is organic. Rank of coal is lignite B to sub bituminous C. Its heating value varies 5503-9452 (mmmf). The coal is dull black and contains a lot of resin. The moisture content is 27%. It is often susceptible to spontaneous combustion. Ahmed et al. (1986) estimated 300mt. Ghaznavi (2002) estimated 1,328mt with 244mt measured, 629mt indicated and 455mt inferred. Mineable reserves are 60% of the measured reserves. The coal is being used for brick kiln, power generation and cement factories. Sonda-Thatta Coalfields Sonda-Thatta Coalfields (Thatta district) are located east and west of Indus River. It shows two horizons of coal. The lower coal horizon belongs to Bara Formation and upper coal horizon belongs to Sohnari Formation of Laki group. Most of the coal deposits are of Bara Formation. 10 coal zones have been recognised. Each zone shows 1-5 coal seams which are 5-10m apart with 0.5-15m thickness of each zone. The maximum coal thickness is 2.40m and minimum coal thickness is 0.07m. Sohnari Formation shows a few relatively thin (09.34m) coal seams. It is deposited in lower delta plain with reed marsh in oxic-anoxic conditions. The swamp seams indicate low water-table with dry and high degradational environments in the past. These coalfields show in place total resources (alongwith Ongar and Indus east) of about 5,789mt with 129mt measured, 758mt indicated and 4902mt inferred reserves. Whilst resources with 0.6m cut off grade is 3766mt with detail as 85mt measured, 495mt indicated and 3186mt inferred. The Jherruk area show thickest coal seams and is the extension of Sonda coalfield. The total resources of Jherruk block is 1.8mt and over 1.2bt with 0.6m cut off grade. The resources of Jherruk block is 1823mt with 106mt measured, 810mt indicated and 907mt inferred whereas the reserves are (0.6m cut off grade) 1282mt with 75mt measured, 572mt indicated and 635mt inferred. Jherruck Coalfields Jherruck Coalfields show reserves of 1823mt, whilst those at Ongar Coalfields, Indus East Coalfields and Badin Coalfields have reserves of 312mt, 1777m and 850mt, respectively. Meting-Jhimpir Coalfields Meting-Jhimpir Coalfields (Thatta district) is 125km east of Karachi on the vicinity of Meting and Jhimpir railway stations. Railway line runs on the western limit of the Karachi-Hyderabad highway limit with the eastern boundary of coalfields. It is found in the Early Eocene Sohnari Formation of Laki group. There is 1 coal seam (0.3-1m with aver 0.6m) which is thin and lenticular. The dips are gentle with 100 west, the ash and sulphur contents are relatively low, ranks are lignite A to sub bituminous C whilst the composition splits into moisture at 26.6-36.6%, volatile matter at 25.2-34%, fixed carbon between 24.1 and 32.2%, ash at 8.2-16.8, sulphur 2.9-5.1% and heating value 67257660BTU/lb (Ahmed et al. 1986) with total reserves of 161mt detailed as 10mt measured, 43mt indicated and 108mt inferred reserves. Small scale mining is in progress. Petroleum Resources Asia contains 75% of oil and 78% of global gas reserves. The Asian reserves are however concentrated in the Middle Eastern countries around the Persian Gulf where 65% of the world 36 known reserves are located and other Asian countries have 10% of global oil reserves. The other continents have 25% oil reserves while Asia alone has 75% (Siddiqui, N.K. 2004)”. Petroleum is known from Kohat area of Pakistan since 1833. First well was drilled at Kundal in Khisor range (KP) during 1866, soon followed by borings near Khattan (Balochistan). The first commercial oil discovery was done in 1920 when Attack Oil Company discover the Khaur oil field in Potwar Plateau. In 1879 survey for petroleum in Punjab reported many oil seepage (Heron and Crookshank 1954). Since early to now many oil and gas seepage have been reported in various localities of Punjab, KP, Sindh and Balochistan. In the early oil shows were considered significant for petroleum exploration though now lost their importance, they are still of interest to search for petroleum (Kazmi and Abbas 2001). Oil resources are frequently being developed from upper Indus basin, while gas resources are being developed from middle and lower Indus basin. The 716 exploratory wells with 213 discoveries, 67 of oil and 146 of gas and condensate have been drilled until July 2008 (Energy year book 2008). Giants gas fields are Sui, Mari, Uch and Qadir Pur, Majors are Pir Koh and Khairpur. Indus Basin (533,500 km2) subdivided in to northernmost (uppermost) Indus, northern (upper) Indus, Central/middle Indus and southern/lower Indus basins. The rectangle shape Sulaiman Basin is the largest basin of main Indus Basin and consists of more than 170,000 km2, while the triangle shape Kirthar basin more than 120,000 km2, square shape Kohat and Potwar basin more than 100,000 km2and almost square shape Khyber-Hazara-Kashmir basin more than 100,000 km2. The Western Indus Suture (Lasbela-Khuzdar-Quetta-Muslimbagh-Zhob-Waziristan-Kuram) and Northern Indus Suture (Mohmand-Swat-Besham-Sapat-Chila-Haramosh-Astor-Shontar-Burzil PassKargil), Kirana and Nagar Parkar areas show more than 50,000 km2. Kirthar Basin (Southern/lower Indus) consists of exposed Mesozoic to recent rocks (Malkani 2010a,2012k; Malkani and Mahmood 2016b) more than 15km thick. However the Nagar Parker area contains Precambrain Ignesous rocks of Indo-Pak shield. Kirthar basin consists of Kirthar fold and thrust belts, Jacobabad-Khairpur high/horst (Sukkur Rift), Kirthar depressions and Sindh monocline. The main reservoir rocks in Sindh monocline are Cretaceous Mekhtar Sandstone/Mekhtar Formation (Lower Goru sandstone) and from Karachi Depressions production is from Paleocene Ranikot group limestone and sandstone. The Cretaceous Mekhtar Sandstone/Mekhtar Formation (commonly called lower Goru sandstone) was named by Malkani (2010a) as member but Malkani and Mahmood (2016b) upgraded it as Mekhtar Formation (Mekhtar Sandstone) for sandstone well exposed in Mekhtar (Loralai District) and Murgha Kibzai (District Zhob), Balochistan (Sulaiman foldbelt). It is found in subsurface in Sindh as Lower Goru sandstone. In Kirthar depressions and Jacobabad-Khairpur high/Sukkur rift zone it may be from Eocene Habib Rahi and Paleocene Dungan limestone. This basin contains best reservoir (sandstone/limestone), source (mostly shale) and cap rocks (shale) briefly mentioned here. Triassic Khanozai Group represents Gwal (shale, thin bedded limestone) and Wulgai (shale with medium bedded limestone) formations. Jurassic Sulaiman Group represents Spingwar (shale, marl and limestone), Loralai/Anjira (limestone with minor shale), Chiltan (Zidi/Takatu; limestone) and Dilband (iron stone) formations. Early Cretaceous Parh Group represents Sembar (shale with a sandstone body), Mekhtar (sandstone, commonly called lower Goru), Goru (shale and marl), and Parh (limestone) formations. Late Cretaceous Fort Munro Group represents Mughal Kot (shale/mudstone, sandstone, marl and limestone), Fort Munro (limestone), Pab (sandstone with subordinate shale) and Vitakri (red muds and greyish white sandstone) formations. Paleocene Sangiali Group in the 37 western Kirthar represents Sangiali (limestone, sandstone, shale with common bivalves), Rakhi Gaj (sandstone and shale) and Dungan (limestone and shale) formations. Paleocene Ranikot Group in the eastern Kirthar basin (Laki and surroundings) represents Khadro (limestone, sandstone, shale and volcanics), Bara (soft sandstone, shale and coal) and Lakhra (limestone with subordinate shale) formations. Early Eocene Chamalang (Ghazij) Group in the western Kirthar represents Shaheed Ghat (shale), Toi (sandstone, shale, rubbly limestone and coal), Kingri (red shale/mud, grey and white sandstone), Drug (rubbly limestone, marl and shale), and Baska (gypsum beds and shale) formations. Early Eocene Laki Group in the eastern Kirthar basin (Laki range and surroundings) represents Sohnari (lateritic clay and shale, yellow arenaceous limestone pockets, ochre and lignitic coal seams) and Laki (limestone with subordinate shalel) formations. Early-Middle Eocene Kirthar Group represents Kirthar (limestone, marl and shale) and Gorag (resistant and peak forming limestone with negligible shale and marl) formations. Oligocene-Miocene Gaj Group represents Oligocene Nari (sandstone, shale, limestone) and Miocene Gaj (shale with subordinate sandstone and limestone) formations. Late Miocene-Pliocene Manchar Group represents Late Miocene Litra (greenish grey sandstone with subordinate conglomerate and mud), and Pliocene Chaudhwan (mud, sandstone and conglomerate) formations. Pleistocene-Holocene Sakhi Sarwar Group represents Dada (well developed conglomerate with subordinate mud and sandstone) and Sakhi Sarwar Formation (poorly developed conglomerate with subordinate mud and sandstone, while in centre of valleys the mud is dominant) which are concealed in the valleys and plain areas by the Subrecent/Recent fluvial, eolian and colluvial deposits. Thar and some coastal consists of eolian sand dune deposits. Radioactive Mineralresources The primary (uranium, may be thorium, etc) and secondary (uranophane, metatyuyamunite, carnotite, etc) are found in fluviatile cross bedded sandstones/placer of Vihowa/Manchar group, as derived from igneous rocks of northern Pakistan. Geothermal Energy Resources Some hot springs may be found in Kirthar foldbelt but not economic so far. Water Resources and Dam Constructions Water resources of the Sindh Province are too much but needs its utilization. It has many valleys and plain areas inside, have many larger fans and surrounding plain lands for cultivation, suitable for many smaller and also larger dam construction, and also fore deep (Daman) of Kirthar foldbelts which have much barren areas, demands for urgent dams construction. Many gorges are also suitable for smaller dam for water storage for cultivation and population which can play best for the development of the area. In short, the barren areas can be converted into cultivation and vegetation by some efforts. Water resources wasting as flood suggests for small dams construction especially in Kirthar and its Daman areas which holds its vast plain areas. Water resources have also large potential in alluvial and bed rocks (Malkani 2012a). Natural Resources The minerals, coal, oil, natural gas, etc are non-renewable resources while the solar, air/wind, terrestrial water, marine water/ocean, tides, waves, current, land, biomass, etc are renewable 38 (recycled) resources. It is our urgent need to convert the non conventional energy resources into conventional energy resources. Kirthar land is receiving huge amount of energy from sun. The coastal areas have high potential of wind energy. Gravitational force of moon produces tidal energy in sea which can be converted in energy by the construction of dams which can store water at high tides and release water at low tides. Sindh has a long sea shore from Nagar Parker to west of Karachi. Energy from sea waves can also be benefited by stable and non stable plate’s movements. Sindh also has a large waste biomass. MINERAL RESOURCES OF INDUS OFFSHORE Pakistan has a long sea with Indus and Makran onshore and offshore regions. The Indo-Pak Sea and their offshore can be explored for economic minerals. The sea mund may be explored for manganese nodules containing zinc, copper, silica, nickel, cobalt and phosphates. According to Roonwal (1986) the common salt, magnesium and bromine have long been extracted from sea water. Sand and gravel, tin bearing sands, magnetite sands and calcium carbonate are already being mined. According to Roonwal (1986) as traditional mineral deposits become depleted and technological developments make ocean mining more feasible. In sea there is no need of removing overburden. The marine minerals are open deposits lying on sea floor and continental slopes, etc. The shallow sea contains relatively large thichness of placers while the deep sea which contains very low thickness of muds. The sea beds of Indian ocean contains a variety of exploitable resources ranging from beach sand and gravel, through heavy minerals associated with beach deposits of phosphorite and manganese nodules to subsurface petroleum reserves. The marine minerals may be explored by simple technology like under water photography, inexpensive coring and sampling. The manganese nodule survey need a simple free ball grabs system for sampling, estimating and photographing. The methods are available for shallow areas while deep water areas need special technology. The marine minerals are present in all parts of the ocean while metallic minerals containg zinc, lead, copper, cobalt, nickel occur in mid oceanic ridge systems and deep ocean plains away from continents. The smelter for these deposits is also worth. The Pacific floor is estimated 1.5 trillion tons of manganese nodules which are also rich in copper, cobalt, nickel, and other metals (Roonwal 1986). Likwise Indo-Pak ocean floor may have also significant manganese nodules, so try should be made. In many cases both onshore and offshore can yield best results. MINERAL RESOURCES OF NAGAR PARKER (A REMNANT OF INDO-PAK SHIELD), SINDH PROVINCE Potash/Orthoclase Feldspar It is associated with acidic group while sodic feldspar is associated with intermediate and basic group. It is used in ceramic and glass industry. The potash and sodic feldspar occur widespread in Nagar Parker area of southeastern Sindh Province. Construction, Dinension and Decorative Stone Resources Different type and varicolour granites and other plutonic igneous (dolerite, etc) along with some metamorphic rocks are found in Nagar Parker Igneous Complex area (Jan 2016; verbal 39 communication of Principal author with Qasid Jan) which are significant for construction and dimension stone resources. INSTALLATION OF MUSEUMS, GLOBAL AND NATIONAL GEOPARKS-AN INNOVATION FOR SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT OF PROVINCES AND PAKISTAN Pakistan has wonderfully exposed diverse tectonic elements like convergent collision of IndoPakistan with Asia (continent-continent collision), Chaman-Uthal regional transform fault and active subduction like convergent of Arabian sea plate with Balochistan basin of Tethys sea plate, different types of igneous, metamorphic and sedimentary rocks, sedimentary rocks and minerals, typical sedimentary and tectonic structures, diverse topography like sea coast in the south, plain areas in the central east, some world class peaks in the north. Pakistan includes Gondwanan, Laurasian and Tethyan heriaege. So its paleontology, paleobiogeography, geodynamics and tectonic evolution are critical among world scientists because its Indus Basin was attached to Gondwana in the past but now connected with Asia. Pakistan is museum for many significant invertebrates and vertebrates. We should construct large museums with bones where the national and international researchers, students and visitors can access easily. The world scientists take interest to work in Pakistan and our students get abroad higher studies scholarship, all these go to the development of Pakistan. The recent finding of fossils of walking whales (Gingerich et al. 2001) and basilosaurids-king of the basal whale (Malkani et al. 2013), baluchitheres-the largest land mammals (Malkani et al. 2013), dinosaurs and mesoeucrocodiles (Malkani and Anwar 2000; Malkani et al. 2001; Malkani 2003, 2004e, 2006a,b,c, 2007b,c,d,e, 2008a,b,c,d,e, 2009a,b,c,d,e, 2010a,b,c,d,e,f, 2011b,c, 2012f,g,h,i,j, 2013c,d,e,f,g,h,i, 2014c,d,e,f,g, 2015b,c,d,e,f,g, 2016c,d; Malkani and Sun 2016; Wilson 2010; Wilson et al. 2001,2005), pterosaurs (2013c, 2014d, 2015c), many footprints and trackways of small and large theropods and herd of titanosaurian sauropod dinosaurs (Malkani 2007a,2008a,2014c,2015c,d,e,f), first trackways of titanosaurian sauropod dinosaurs from Asia found from Pakistan (Malkani 2007, 2008a, 2015c,d,e,f), articulated atlas-axis of titanosaurs (Malkani 2008b), first osteoderms of titanosaurs reported in Asia found from Pakistan (Malkani 2003b,2010c,2015c,g,h), large proboscideans and other vertebrates (Malkani 2014e,2015c; Malkani and Sun 2016; Raza and Meyer 1984, etc) from Pakistan are unique gifts for the world. 40 Chronostratigraphy Chronostratigraphy Age Eastern&Western Kirthar (Lower Indus) Sulaiman (Middle Indus) Kohat – Potwar (Upper Indus) Recent Alluvium,Eolian,Colluv. Holocene Sakhi Sarwar Pleistocene Dada …… Pliocene Chaudhwan …… Litra Miocene Gaj Oligocene Nari Alluvium Sakhi Sarwar Dada …… Chaudhwan Litra Vihowa ……Chitarwata A l l u v i um Soan L e i …… Dhok Pathan / Murree U Nagri / Murree M …… Chinji / Murree L Laki L/ Kirthar Sohnari U /Baska Drazinda Pir Koh Domanda Habib Rahi Baska Drazinda Kuldana Pirkoh Domanda Habib Rahi Chorgali Bahadurkhel,Jatta Sohnari M/ Drug Sohnari M/ Kingri Sohnari L/ Toi …Sohnari L/Shaheed Ghat Lakhra/Dungan Paleocene Bara/Rakhi Gaj Khadro/Sangiali Drug Kingri Toi Shaheed Ghat Dungan Rakhi Gaj Sangiali Shekhan Sakesar Gurguri Chashmai Panoba Nammal Lockhart Laki U/ Gorag Eocene H a n g u ……Disconformable Boundary... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... .. Cretaceous …… Jurassic Triassic Sandstone Vitakri Pab Fort Munro Mughal Kot Parh Goru Mekhtar Sembar Dilband Chiltan Anjira Spingwar. Wulgai Gwal Limestone Sauropod dinosaur Vitakri Pab Fort Munro Mughal Kot Parh Goru Mekhtar Sembar Dilband Chiltan Loralai Spingwar. Wulgai Gwal Dolomite Conglomerate Theropod dinosaur Shale Indus Kawagarh L u mshiwal C h i c h ali Samanasuk Shinawari Datta Kingriali/Chalk Jabi Tredian Mianwali Marl Mesoeucrocodile Gypsum/salt Alluvium Pterosaur-flying reptile Figure 1. Revised Stratigraphic Correlation of Lower Indus (Eastern and Western Kirthar), Middle Indus (Sulaiman) and Upper Indus (Kohat-Potwar) basins of Pakistan. Abbreviations; L-Lower, M-Middle, U-Upper. 41 Map of Pakistan showing major mineral localities: Copper Legend Iron Lead-Zinc Chromite Magnesite Gold Coal Fluorite Celestite Gypsum Uranium Sulphur Manganese Mica Graphite Soapstone Asbestos Silica Sand Fuller Earth China clay Fire clay Salt Barite Phosphate Figure 2. Map of Pakistan showing major mineral localities of Western and Eastern Kirthar basin (lower Indus basin). References Abbas S.G. 1980a. Kharrari Nai; Bhampani Dhoro and Porar Dhoro Manganese deposits, Lasbela. Geological Survey of Pakistan (GSP), Information Release (IR) No. 122. Abbas S.G. 1980b. A Preliminary report on the discovery of massive sulphide type copper deposit in the Axial belt of Las Bela District, Balochistan. GSP, IR 136. Abbas S.G. 1989. A short note on chromite occurrence of Sonaro area, Khuzdar. GSP, P&I file. Unpublished report. Abbas S.G., Ahmad W. 1974. A note on geology and geochemistry of copper mineralization, Paha area, Lasbela. GSP, IR 86. Abbas S.G., Kakepoto A.A., Ahmad M.H. 1997. Iron ore deposits of economic significance from Dilband area, Kalat District, Balochistan, Pakistan. Nat. Symp. On economic geology of Pakistan. April 2-3, Pak. Mus. Nat. Hist. Abstract. Abbas S.G., Kakepoto A.A., Ahmad M.H. 1998. Iron ore deposits of Dilband area, Mastung district, Kalat Division, Balochistan. Geological Survey of Pakistan (GSP), Information Release (IR) No. (679): 19p. Abbas S.G., Sultan M, Bahadur S. 1980. Geology and Economic potential for fluorite in Dilband, Maran and Pad Maran areas, district Kalat, Balochistan, Pakistan. Geol. Surv. Pakistan. Unpublished Report. Afzal J., Khan M.A., Ahmed S.N. 1997. Biostratigraphy of Kirthar Formation (middle to late Eocene), Sulaiman Basin, Pakistan. Pakistan Jour. Hydroc. Res. 9, 15-33. Ahmad M.I., Klinger F.L. 1967. Barite deposits near Khuzdar. Pak-series report 21, GSP-USGS publication. Ahmad N., Qaiser M.A., Alaudin M., Amin M. 1987. Physico-chemical properties of some indigenous clays. Pak. J. Sci. Ind. Res. (30): 731-734. Ahmad W. 1954. Red ochre of Thatta district, note. GSP, file 379. 42 Ahmad W. 1981. Metallogenic framework and mineral resources of Pakistan. Chika Shigen Chosago Hokoku, Japan, 261, 47-76. Ahmad W. et al. 1986. Coal resources of Pakistan. GSP, Rec. 73, 55p. Ahmad Z. 1969. Directory of Mineral deposits of Pakistan. GSP, Rec. 15(3): 200p. Ahmad Z. 1975. Directory of Mineral deposits of Balochistan. GSP, Rec. (36): 178p. Ahmad Z., Bilgrami S.A. 1987. Chromite deposits and ophiolites of Pakistan. In Clive W. Stow (eds.), Chrom. ore, Van Norstrand Reinhold Co. N. Y., 239-269. Ahsan S.N., Khan K.S.A. 1994. Pakistan mineral prospects: lead and zinc. Int. round table conf. on Foreign investment in Exploration and mining in Pakistan, Ministry of Petroleum and Natural resources, Islamabad, 10p. Ahsan S.N., Qureshi I.H. 1997. Mineral/Rock resources of Lasbela and Khuzdar districts, Balochistan, Pakistan. Geol. Bull. Peshawar, (30): 41-52. Ahsan N. 2006. Exploration of the Iron Ore Occurrences near Nuriabad, Dadu District, Sindh, Pakistan. Geological Survey of Pakista, Information Release No.830. Akhtar M.J., Rizvi Y., Muhammad A., Tagar M.A. 2012. Geological Map of Sindh, Pakstan. Scale 1:600,000. Ali S.T. 1963. Iron ore resources of Pakistan. CENTO Symp. Iron Ore. Isphahan, 55-60. Ali T., Shahzada K., Gencturk B., Naseer A., Alam B., Javed M. 2012. Role of concrete industry as remedy for the plastic wast e disaster. Abstract Volume, Earth Sciences Pakistan, Baragali Summer Campus, University of Peshawar, June 23-24, Pakistan, Journal of Himalayan Earth Sciences, 45 (2), 17-18. Alizai A.H.,, Mir M.A. Chandio A.H. 2000. Gypsum deposits of Johi, Khairpur Nathan Shah areas, Dadu district. GSP, IR 731,13p. Anwar M., A.N. Fatmi and I.H. Hyderi. 1991. Revised nomenclature and stratigraphy of Ferozabad, Alozai and Mona Jhal groups of Balochistan (Axial Belt), Pakistan. Acta Mineral Pakistanica 5, 46-61. Anwar M., Fatmi A.N., Hyderi I.H. 1993. Stratigraphic analysis of the Permo-Triassic and lower-middle Jurassic rocks from the Axial Belt region of the northern Balochistan. Geol. Bull. Punjab Univ. 28:1-28. Arif S.J., Malkani M.S. 2016a. Geoheritage and Paleobioheritage of Pakistan; Museums, National and Global Geoparks-a media for Researcher and Public Education. Abstract Volume, Earth Sciences Pakistan 2016, 15-17 July, Baragali Summer Campus, University of Peshawar, Pakistan, Journal of Himalayan Earth Sciences, 23. Arif S.J., Malkani M.S. 2016b. Coal resources of Punjab (Pakistan): an overview. Abstract Volume, Qazi, M.S., Ali, W. eds., International Conference on Sustainable Utilization of Natural Resources, October 03, National Centre of Excellence in Geology, University of Peshawar, Peshawar, Pakistan. Journal of Himalayan Earth Sciences, 14. Arkell W.J. 1956. Jurassic Geology of the World. Oliver & Boyed, London, 806p. Asrarullah 1963. Marble deposits of west Pakistan. CENTO Symp. Indust. Rocks and Min. 179-188. Asrarullah 1978. Iron ores of Pakistan. Proc. National Seminar on Mineral Resources. Lahore, 116-137. Asrarullah 1978. Iron ores of Pakistan. GSP, IR 108. Asrarullah, Hussain A. 1985. Marble deposits of North Western Frontier Province, Pakistan. GSP, IR (128): 23p. Bakar M.A. 1962. Fluorspar deposits in the northern part of Koh-i-Maran Range, Kalat division, West Pakistan. Geol. Surv. Pakistan, Record volume 9(2), 7p. Bakar M.A. 1965a. Fluorspar deposits of Pakistan. GSP, Rec. 16(2), 5p. Bakar M.A. 1965b. Vermiculite deposits of Pakistan. GSP, Rec. 16(1), 1-9. Bakht M.S. 2000. An overview of geothermal resources of Pakistan. In; proceedings world geothermal congress 2000, Kyushu, Tohoku, Japan, 947-952. Basham I.R., Rice C.M. Uranium mineralization in Siwalik sandstones from Pakistan. In; Formation of uranium ore deposits, Proc. Symp. Athens, IAEA, Vienna, Austria, 405-418. 43 Bashir E. 2008. Geology and geochemistry of Magnesite ore deposits of Khuzdar area. Depart. of Geology, Univ. of Karachi. Ph. D. thesis, 391p Bhola K.L. 1947. Bentonite in India. Geol. Mining Metall. Soc. India. Journ. Vol. 19 (2), 55-57. Bilgrami S.A. 1982. Mineral industry of Pakistan. Resources for the 21 st Century, RDC, Karachi, 168-178. Bilqees R., Shah M.T. 2004. Mineralogical and geochemical evaluation of limestone deposits of Kohat, KPK (Pakistan) for a sustainable industrial development. In abstract volume National Conference on Economic and Environmental sustainability of Mineral resources of Pakistan, Baragali, Pakistan, 18. Blanford W.T. 1872. Note on the geological formations seen along the coasts of Balochistan and Persia from Karachi to head of the Persian Gulf, and on some of the Gulf islands. Ibid, Records, pt 2, 41-45. Blanford W.T. 1879. The geology of western Sind. Ibid, Mem. Vol. 17, 1-196. Bogue R.G. 1961. Celestite deposits near Thano Bula Khan, Hyderabad Division, West Pakistan. Geological Survey of Pakistan (GSP), Mineral Information Circular, 18p. Boyd J.T. Company 1985. Overview of Lakhra coalfield, Lakhra coal project, Sindh, Pakistan. John T. Boyd Company, report number 1800, vol 5, 115p. Brownfield M.E., et al. 2005. Characterization and models of occurrence of elements in feed coal and coal combustion products from a power plant utilization low sulfer coal from the Powder River basin, Wyoming. Scientific Investigation Report 2004-5, 271. U.S.G.S. Virginia, 36p. Buzdar M. A., Malkani M. S., 2016. Major bioevents, extinction of land vertebrates, Cretaceous-Tertiary boundaries in Indo-Pakistan subcontinent (South Asia).Abstract Volume, Earth Sciences Pakistan 2016, 15-17 July, Baragali Summer Campus, University of Peshawar, Pakistan, Journal of Himalayan Earth Sciences, 31. Cheema M.R., Raza S.M., Ahmad H. 1977. Cenozoic. In. Shah ed. Stratigraphy of Pakistan. GSP, Mem. 12, 56-98. Chemical Consultants (Pakistan) Ltd. 1985. Final report: Feasibility study on the utilization of coal in substitution of other fuels: vol.1, Coal resources of Pakistan, prepared for ministry of petroleum and natural resources, 136p. Clavarino J.G., Dawney R.L., Sweatman T.R. 1995. Gold exploration in northern areas, status and prospects. In proceedings of Intern. Round table conference (1994) and foreign investment in Exploration and mining in Pakistan, Govt of Pakistan and UN, 93-120. Cooper C.F. 1911. Paraceratherium bugtiensis, a new genus of Rhinoceratidae from Bugti hills of Balochistan. Geol. Surv. India Mem. 40, 65p. Cooper C.F. 1923. Carnivora from the Dera Bugti deposits of Balochistan. Ann. Mag. Nat. Hist. Ser. 9, vol. 12, 259-263. Cooper, C.F. 1924a. Baluchitherium osborni, syn. of Indricotherium turgacium Borrissyak, Roy. Soc. London, Phill. Trans. Ser. B. Vol. 212, 35-45. Cooper C.F. 1924b. On the skull and dentition of Paraceratherium bugtiensis a genus of aberrant Rhinoceroses from the Lower Miocene of Dera Bugti. Phill. Trans. Royal SDC. London, 212, 369-384. Cooper C.F. 1924c. The Anthracotheridae of the Dera Bugti deposits in Balochistan. India Geol. Surv. Mem. Paleontolog. Indica, New Series, v. 8, Mem.2, 59p. Cruijs H. 1975. Report on investigations conducted on mineral substances in Pakistan on behalf of PMDC. United Nations, ESCAP, Bangkok, 49p. Davies L.M. 1926. The Ranikot beds of Thal (NWFP). Geol. Soc. London, Quart. Journ. Vol. 83, 206-290. Davies L.M. 1941a.Correlation of Laki beds. Geol. Mag. Vol. 78, 151-152. Davies L.M. 1941b.The Dungan limnestone and Ranikot beds in Balochistan. Ibid vol 78, 316-317. Davies L.M., Pinfold E.S. 1937. The Eocene beds of the Punjab Salt Rabge, Geol. Surv. India., Mem., Paleont. Indica, New series vol. 24, no. 1, 79p. Davies R.G., Crawford A.R. 1971. Petrography and age of the rocks of Bulland hill, Kirana hills, Sargodha district, Pakistan. Geol. Magaz 108 (3), 23-246. 44 Dhanotr M.S.I. 2015a. Lithofacies of Latest Cretaceous Vitakri Formation in Central Sulaiman fold & thrust belt (Middle Indus Basin) of Pakistan. University of Balochistan, M. Phil Thesis, 98pp. Dhanotr M.S.I. 2015b. Lithofacies Distribution and interpretation of Latest Cretaceous Vitakri Formation in Central Sulaiman fold & thrust belt (Middle Indus Basin) of Pakistan. Geol. Surv. Pak., Information Release. 956;34pp. Dhanotr M.S.I 2015c. Petrography & Provenance of Latest Cretaceous Vitakri Formation in Central Sulaiman fold & thrust belt (Middle Indus Basin) of Pakistan. Geol. Surv. Pak., Information Release. 958;41pp. Downing K.F., Lindsey F.H., Downs W.R., Speyer S.E., 1993. Lithostratigraphy and vertebrate biostratigraphy of the early Miocene Himalayan Foreland, Zinda Pir Dome, Pakistan. Sed. Geol. 87, 25-37. Duncan P.M. 1880. Sind fossil corals and Alcynoria: India Geol. Surv. Paleont. Indica ser. 7, 14, vol. 1, 110p. Duncan P.M., Sladen W.P. 1884-86. Tertiary and upper Cretaceous fossils of western sind; Fasc. 2, the fossil Echinoidea from Ranikot series of Nummulitic strata in western sind: Ibid, Mem., Paleont. Indica, ser, 14, vol. 1, no. 3, 25-100. Duncan P.M., Sladen W.P. 1882. Tertiary and upper Cretaceous fossils of western sind; Fasc. 5, the fossil Echinoidea from Gaj Miocene series: Ibid, Mem., Paleont. Indica, ser, 14, vol. 1, no. 3, 273-367. Eames F.E. 1950. On the age of the fauna of the Bugti bone beds, Balochistan: Geol. Mag. 87 (1), 53-56. Eames F.E. 1952. A contribution to the study of the Eocene in West Pakistan and western India; Part A, The geology of standard sections in the western Punjab and in the Kohat district. Part B, Description of the fauna of certain standard sections and their bearing on the classification and correlation of the Eocene in Western Pakistan and Western India. Quart. J. Geol. Soc. London, 107, pt. 2, 159-200. Eames F.E. 1970. Some thoughts on the Neogene/Paleogene boundary. Paleogeography, Paleoclimatology, Paleoecology, 8, 37-48. Eames F.E. 1939. Fossils from the Khojak slates, Balochistan. Geol. Surv. India, Rec. Vol. 74, 552-554. Eames F.E. 1950. On the age of the fauna of the Bugti bone beds, Balochistan: Geol. Mag. 87 (1), 53-56. Eames F.E. 1952. A contribution to the study of the Eocene in West Pakistan and western India; Part A, The geology of standard sections in the western Punjab and in the Kohat district. Part B, Description of the fauna of certain standard sections and their bearing on the classification and correlation of the Eocene in Western Pakistan and Western India. Quart. J. Geol. Soc. London, 107, pt. 2, 159-200. Eames F.E. 1970. Some thoughts on the Neogene/Paleogene boundary. Paleogeography, Paleoclimatology, Paleoecology, 8, 37-48. Fassett J.E., Durani N.A. 1994. Geology and coal resources of Thar coalfield, Sindh, Pakistan. USGS open file report, 94-167, 74p, Reston, Va. Fatmi A.N. 1968. The paleontology and stratigraphy of the Mesozoic rocks of western Kohat, Kala Chitta, Hazara and Trans-Indus Salt ranges, west Pakistan. Ph. D. Thesis, University of whales, unpub. 409p. Fatmi A.N. 1969. Lower Callovian Ammonites from Wam Tangi, Nakus, Balochistan. GSP,Mem. 8, 9p. Fatmi A.N. 1977. Mesozoic. In: Stratigraphy of Pakistan, (Shah, S.M.I., ed.), GSP, Memoir, 12, 29-56. Fatmi A.N., Hyderi I.H., Anwar M., Mengal J.M, Hafeez M., Khan M.A. 1999. Stratigraphy of Mesozoic rocks of southern Balochistan, Pakistan. GSP, Rec. 85(1). Fatmi A.N. et al. 1986. Stratigraphy of Zidi formation (Ferozabad group) and Parh group (Mona Jhal group), Khuzdar district. GSP, Rec. 75, 32. Fatmi A.N. et al. 1999. Stratigraphy of Mesozoic rocks of southern Balochistan. GSP, Rec. 85, pt. 1. Fatmi A.N. 1969. Lower Callovian Ammonites from Wam Tangi, Nakus, Balochistan. GSP,Mem. 8, 9p. Fatmi A.N. 1977. Mesozoic. In: Stratigraphy of Pakistan, (Shah, S.M.I., ed.), GSP, Memoir, 12, 29-56. Fatmi A.N., Hyderi I.H., Anwar M., Mengal J.M, Hafeez M., Khan M.A. 1999. Stratigraphy of Mesozoic rocks of southern Balochistan, Pakistan. GSP, Rec. 85(1). Fatmi A.N. et al. 1986. Stratigraphy of Zidi formation (Ferozabad group) and Parh group (Mona Jhal group), Khuzdar district. GSP, Rec. 75, 32. 45 Flynn L.J. 2000. The great small mammalian revolution. Himal. Geol. 21, 1-13. Fox C.S. 1923. The bauxite and aluminous laterite of India. GSI, Mem. 49, 1-287p. Fritz E.B., Khan M.R. 1967. Cretaceous (Albian-Cenomanian) planktonic foraminifera in Bangu Nala, Quetta division, west Pakistan. U.S.Geol. Surv. Proj. Report (IR) PK-36, 16p. Gauher S.H. 1966. Cement resources of Pakistan. GSP, PPI 11, 44p. Gauher S.H. 1969. Economic minerals of Pakistan: a brief review. GSP, PPI 88, 110 pages, 21 tables. Gauhar S.H., Khan S.H., Sultan M. 1976. The survey of Raw materials around prospective sites for acement factory in Balochistan. GSP, IR 92. Gauher S.H. 1992. Plate tectonics, crustal evolution and Metallogeny of Pakistan. GSP, IR 525, 27p. Gee E.R. 1945. The age of the Saline series of Punjab and Kohat: India Nalt. Axad. Sci. B., vol. 14, pt. 6, 269-310. Gee E.R. 1949. Mineral resources of north west India. GSP, Rec. 1(1), 25p. Ghani M.A., Harbour R.L., Landis E.R. 1973. Geology and coal resources of Lakhra coalfield Hyderabad area, Pakistan. USGS project report Pakistan investigation (IR) PK-55, 78p. Ghaznavi M.I. 1988. The petrographic properties of the coals of Pakistan. (M.S. thesis), Carbonadale, Southern Illinois University, 175p. Ghaznavi M.I. 2002. An overview of coal resources of Pakistan. GSP, Pre Publication Issue of Record vol. no. 114; 167p. Gigon W.O. 1962. The upper Cretaceous Stratigraphy of the well Giandari-I and its correlation with the Sulaiman and Kirthar Ranges, west Pakistan. ECAFE Symposium on Development Petroleum Resources Asia and Far East, Tehran, 282-284. Gill W. D. 1952. The stratigraphy of Siwalik series in the northern Potwar, Punjab, Pakistan. Geol. Soc. London, Quart. Jour., Vol. 107, Pt. 4, 375-394. Grant R.E. 1970. Brachiopods from Permian-Triassic boundary beds and age of Chidru formation, west Pakistan. In Kummel and Teichert eds, stratigraphic boundary problems, permotriassic of west Pakistan. Univ. Kansas Geol. Deptt. Spec. Pub. No. 4, 117-151. Gingerich P.D., Arif M., Khan I.H., Haq M., Baloch J.J., Clyde W.C., Gunnel G.F. 2001. Gandhera Quarry, a unique Mammalian faunal assemblage from the Early Eocene at Balochistan (Pakistan). In: Gunnell, G.F. (ed) Eocene biodiversity; Unusual occurrences and rarely sampled Habitats, Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, N.Y; 251-262. Gingerich P.D., Haq M.., Zalmout I.S., Khan I.H., Malkani M.S. 2001. Origin of whales from early artiodactyls: Hands and feet of Eocene Protocetidae from Pakistan; Science, 293: 2239-2242. Gingerich P.D., Raza S.M., Arif M., Anwar M., Zhou X. 1994. New whale from the Eocene of Pakistan and the origin of cetacean swimming. Nature 368, 844-847. Gingerich P.D., Russell D.E., Russell D.S., Hurtenberger J.L., Shah S.M., Hassan M., Rose R.D., Ardrey R.H. 1979. Reconnaissance survey and vertyebrate paleontology of some Paleocene and Eocene formations in Pakistan. Contrib. Mus. Paleont. Univ. Michigan, 25(5), 105-116. Godwin A. M., 1981. Archeanplatesand greenstonebelts. In; Kroner ed. Precambrianplate tectonics, elsevier, amsterdam, 105-135. Griffiths J.B. 1987. Pakistan mineral potential: prince or pauper. Indust. Mineral No. 238: 220-243. Grundstoff-Technik 1992. Pakistan’s mineral wealth. Grundstoff-technik GmbH, Essen., 72p. Hamid K., Alvi U., Khosa L., Mahmood R., Khan S. 2012. Geochemical evaluation of limestone deposits of Pakistan. Abstract Volume, Earth Sciences Pakistan, Baragali Summer Campus, University of Peshawar, June 23-24, Pakistan, Journal of Himalayan Earth Sciences, 45 (2), 31-32. Haque A.F.M.M. 1956. The smaller foraminifera of the Ranikot and the Laki of the Nammal gorge, Salt range. Geol. Surv. Pakistan, Mem. Vol. 1, 300p. Haque A.F.M.M. 1962a. The smaller foraminifera of the Meting limestone (Lower Eocene), Meting, Hyderabad division, west Pakistan. Ibid., Mem. Vol. 2, pt.1, 25p. Haque A.F.M.M. 1962b. Some Late Cretaceous foraminifera from west Pakistan. Ibid., Mem. Vol. 2, pt., 3, 32p. 46 Haque A.F.M.M. 1966. Some Late Tertiary Foraminifera from Makran, west Pakistan. Ibid., Mem. Vol. 28, pt.,1, 96-117. Hemphill W.R., Kidwai A.H. 1973. Stratigraphy of the Bannu and Dera Ismail Khan areas, Pakistan.U.S. Geol. Surv. Prof. Paper 716 B, 36Pp. Hassan M., Bhatti M.A., Bhutta A.M., Abbas S.Q. 2001. Geology and mineral resources of D.G. Khan and Rajan Pur areas, eastern Sulaiman Range. GSP, IR. 747, 107p Heron A.M. 1950. Directory of economic minerals. GSP, Rec. 1(2): 69p. Hasan M.T. 1989. Petrographic characterization of Sonda-Thatta coalfields, Sindh, Pakistan. M.S. Thesis, SIUC Carbonadale USA. Hay O.P. 1930. Second bibliography and catalogue of the fossil vertebrata of North America, volume 2, Carnegie Institution of Washington, Washington D.C., 390(2): 1-1074. Hemphill, W.R., Kidwai A.H. 1973. Stratigraphy of the Bannu and Dera Ismail Khan areas, Pakistan. U.S. Geol. Surv., Prof. Paper 716 B, 36p. Heron A.M. 1950. Directory of economic minerals. GSP, Rec. 1(2): 69p. Heron A.M., Crookshank H. 1954. Directory of economic minerals of Pakistan. GSP, Rec. 7(2): 146p. Hunting Survey Corporation 1961. Reconnaissance geology of part of West Pakistan (Colombo plan cooperative project), Toranto, Canadia, 550p. Hussain B.R. 1960. A Geological reconnaissance of the Khisor and Marawat range and a part of Potwar Plateau. Pakistan Shell Oil Co., Karachi, (Unpub), 36p. Hussain B.R. 1967. Saiduwali member, a new name for the lower part of the Permian Amb Formation, West Pakistan. Univ. Studies (Karachi), Sci. and Technol., 4(3), 88-95. Ilyas N., Naseer A., Shah S.F.A. 2012. Energy saving and retarding land pollution by using waste polymers in mortar. Abstract Volume, Earth Sciences Pakistan, Baragali Summer Campus, University of Peshawar, June 23-24, Pakistan, Journal of Himalayan Earth Sciences, 45 (2), 40-41. Iqbal M.W.A. 1969. The Tertiary pelecypod and gastropod fauna from Drug, Zinda Pir, Vidor (Distt. D.G. Khan), Jhalar and Charrat (Distt. Campbellpur), West Pak. GSP. Mem. Paleont. Pakistanica (6): 77Pp. Iqbal M.W.A. 1972. Bivalve and gastropod fauna from Jherruk-Lakhra-Bara Nai (Sindh), Salt Range (Punjab) and Sammana Range (KPK). Geol. Surv. Pakistan, Mem. Vol. 9, 104p. Iqbal Y. 2013. Optimum utilization of local mineral resources. Abstract Volume, Sustainable Utilization of Natural Resources of the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and FATA, February 11, Peshawar, Pakistan. Journal of Himalayan Earth Sciences, Special volume 2013, 14. Islam N.U, Khan S.N., Khan W. Marzban J. 1993. Economic mineral deposits of Pakistan. GSP, unpublished report. Islam N.U, Hussain S.A., Abbas S.Q., Ashraf M. 2010. Mineral statistics of Pakistan. GSP, Special issue. Jadoon, I.A.K. and M.S. Baig. 1991. Tor Ghar, an alkaline intrusion in the Sulaiman fold system of Pakistan. Kashmir Journ. Geol. 8&9, 111-115. Jafry S.S.Q. undated before 2001. Subsurface kaolin occurrences at Islamkot, Tharparker. GSP, unpublish. Jaleel A., Alam G.S., Shah S.A.A. 1999. Coal resources of Thar, Sindh, Pakistan. GSP, Rec. 110,59p. Jan M. Q. 2016. Old wine in new bottle: Reinterpretation of the geochemistry of Wadhari granitoid in Nagar Parker Igneous Complex, southeastern Pakistan. Abstract Volume, Earth Sciences Pakistan 2016, 15-17 July, Baragali Summer Campus, University of Peshawar, Pakistan, Journal of Himalayan Earth Sciences, 59-60. Jankovic S. 1984a. Mineral association and genesis of lead zinc barite deposits at Gunga, Khuzdar District, Balochistan. GSP, Rec. 71: 12p. Japanese Intern. Coop. Agency 1981. Feasibility report of Lakhra coal mining and power station project. JICA, Tokyo, Japan, 424p, 27fig. 4tables. Jones G.V., Shah S.H. 1994. Present status and potential of Duddar zinc-lead deposit. Round Table Conf. on foreign invest. in expl.and mining in Pakistan. 18p. 47 Kakepoto A. A. (2012, in process) Economic Geology, Geochemistry and Depositional Environment of Sedimentary Iron Ores of Kirthar Forebelt and Lower Indus Basin. Ph.D. thesis, Sindh University, Jamshoro, Pakistan. Kazmi A.H., Abbas S.G. 2001. Metallogeney and Mineral deposits of Pakistan. Published by Orient Petroleum Incorporation, Islamabad, Graphic Publishers, Karachi, Pakistan, 264p. Kazmi A.H., Abbasi I.A. 2008. Stratigraphy and Historical Geology of Pakistan. Published by Department and National Centre of Excellence in Geology, University of Peshawar, Pakistan, 524p. Kazmi A.H., Khan M.S., Khan I.A., Fatmi S.F., Fariduddin M. 1990. Coal Resources of Sindh, Pakistan. In; Kazmi, A.H. and R.A. Siddiqi eds. Significance of Coal Resources of Pakistan. GSP-USGS, 27-61. Kazmi A.H., Khan R.A. 1973. The report on the geology, mineral and water resources of Nagar Parker, Pakistan. GSP, IR 64, 1-33. Kazmi A.H., O’Donoghue M. 1990. Gemstones of Pakistan. Gemstone Corporation of Pakistan, 146p. Kella S.C. 1983. Nagar Parker china clay deposits. In proc. Of 2nd national seminar on Dev. Min. Resources, 15p. Khan A. 2012. Overview of mineral sector of Pakistan. Abstract Volume, Earth Sciences Pakistan, Baragali Summer Campus, University of Peshawar, June 23-24, Pakistan, Journal of Himalayan Earth Sciences, 45 (2), 53-54. Khan B. 2004. Marble and granite sector of Pakistan. In abstract volume National Conference on Economic and Environmental sustainability of Mineral resources of Pakistan, Baragali, Pakistan, 35-36. Khan M.A., Raza H.A. 1986. The role of geothermal gradients in hydrocarbon exploration in Pakistan. J. Petrol. Geol. 9(3); 245-258. Khan M.H. 1968. The dating and correlation of the Nari and Gaj Formation. Geol. Bull. Univ. Punjab 7, 57-65. Khan M.J., Hussain S.T. Arif M., Shaheed H. 1984. Preliminary paleomagnetic investigation of the Manchar Formation, Gaj river section, Kirthar range, Pakistan. Geol. Bull. Univ. Peshawar, 17, 145-152. Khan N.M. 1950. Survey of coal resour. Pakistan. GSP, Rec. V.Z, pt.2, 10p. Khan R.A., Philpo J.S., Chaudhry M.A., Tagar M.A., Lashari G.S., Memon A.R. 1993. Coal resources Exploration assessment program (phase -1) Thar Desert, Southern Sindh, Pakistan. GSP, Rec. 98, 1-239. Khan S.H. 2009. Geological map of 39 G degree sheet, Pakistan. GSP map sheet. Khan T., Kausar A.B. 2010. Gems and Gemology in Pakistan. Special Publication of Geological Survey of Pakistan, 231 pp. Khosa M.H., Malkani M.S. 2016. Coal resources of Sindh: Discovery of large lignitic coal deposits in Thar. Abstract Volume, Qazi, M.S., Ali, W. eds., International Conference on Sustainable Utilization of Natural Resources, October 03, National Centre of Excellence in Geology, University of Peshawar, Peshawar, Pakistan. Journal of Himalayan Earth Sciences, 15. Khosa M.H., Malkani M.S., Ali A.M., Hussain U., Dhanotr M.S.I., Arif S.J., Ahmad Y., Dasti N. 2016. Stratigraphy, vertebrate paleontology and economic significance of Zinda Pir anticline, Dera Ghazi Khan district, South Punjab, Pakistan. Abstract Volume, Earth Sciences Pakistan 2016, 15-17 July, Baragali Summer Campus, University of Peshawar, Pakistan, Journal of Himalayan Earth Sciences, 91. Kidwai A.H. 1959. A note on coal of Johan (Kalat state). GSP, unpubl. 5p. Klinger F.L., Abbas S.H. 1963. Barite deposits of Pakistan. CENTO Symp. Indust. Rocks and Min. Lahore, 418-428. Klinger F.L. et al. 1963. Geology of iron deposits of Pakistan. CENTO Symp. Iron ore, Iran, 101-111. Krause W.K. et al. 2006. Late Cretaceous terrestrial vertebrates from Madagascar: Implications for Latin American Biogeography. Ann. Missouri Bot. Gard. 93: 178-208. Kummel B. Teichert C. 1970. Stratigraphy and paleontology of Permian-Triassic boundary beds, Salt range and trans Indus ranges, west Pakistan. Geol Deptt. Univ. Kansas. Spec. Pub.no 4. Landis E.R. et al. 1971. Analyses of Pakistan coals. USGS project report, (IR), PK-58,71p. Latif M.A. 1964. Variations in abundance and morphology of pelagic foraminifers in the Paleocene-Eocene of the Rakhi Nala, West Pakistan. Geol. Bull. Pujab Univ. 4:29-109. Latif M.A. 1970. Micropaleontology of Chanali limestones, upper Cretaceous of Hazara, West Pakistan. Wein Jb. Geol. B.A. Sonderb 15, 25-61. 48 La Touche, T.D. 1893. Geology of the Sherani Hills: India Geol. Surv. Recds, V. 26, pt.3, 77-96, a map & 5 plates. Lexique stratigraphque international. 1956. Vol.3, Asie, fasc. 8, (a) India, Pakistan, Nepal, Bhutan. Centre Nail. Recherche Start., Paris, 404p. Lindsay, E.H., Downs W.R. 2000. Age assessment of the Chitarwata Formation. Himal. Geol. 21:99-107. Malik I.A. 2004. Mineral Sector: Less vision more sight. In abstract volume National Conference on Economic and Environmental sustainability of Mineral resources of Pakistan, Baragali, Pakistan, 43. Malik Z., Kama A., Malik M.A., Bodenhansen J.W.A. 1988. Petroleum potential and prospects in Pakistan. In; Raza and Shaikh, eds., Petroleum for the future. Hydrocarbon dev. Inst. Pak. 71-100. Malkani M.S. 2000. Preliminary report on gypsum deposits of Sulaiman Range, Pak. GSP, IR (706): 1-11. Malkani M.S. 2002. First note on the occurrence of Fluorite in Mula area, Khuzdar District, Balochistan, Pakistan, GSP IR (766): 111. Malkani M.S. 2003a. First Jurassic dinosaur fossils found from Kirthar range, Khuzdar District, Balochistan, Pakistan. Geol. Bul.Univ.Peshawar 36, 73-83. Malkani M.S. 2003b. Pakistani Titanosauria; are armoured dinosaurs?. Geol. Bul. Univ. Peshawar 36, 85-91. Malkani M.S. 2004a. Stratigraphy and Economic potential of Sulaiman, Kirthar and Makran-Siahan Ranges, Pakistan. In abstract volume of Fifth Pakistan Geological Congress, Islamabad, Pakistan, 63-66. Malkani M.S. 2004b. Discovery of Fluorite deposits from Mula-Zahri Range, Khuzdar District, Balochistan, Pakistan. In abstract volume of Fifth Pakistan Geological Congress, Islamabad, Pakistan, 20-22. Malkani M.S. 2004c. Coal resources of Chamalang, Bahney Wali and Nosham-Bahlol areas of Kohlu, Barkhan, Loralai and Musa Khel districts, Balochistan, Pakistan. In abstract volume National Conference on Economic and Environmental sustainability of Mineral resources of Pakistan, Baragali, Pakistan, 44-45. Malkani M.S. 2004d. Mineral potential of Siahan and north Makran ranges, Balochistan, Pakistan. In abstract volume National Conference on Economic and Environmental sustainability of Mineral resources of Pakistan, Baragali, Pakistan, 46-47. Malkani M.S. 2004e. Saurischian dinosaurs from Late Cretaceous of Pakistan. In abstract volume of Fifth Pakistan Geological Congress, Islamabad, Pak, 71-73. Malkani M.S. 2006a. Biodiversity of saurischian dinosaurs from the latest Cretaceous Park of Pakistan. Journal of Applied and Emerging Sciences, 1(3), 108-140. Malkani M.S. 2006b. Cervicodorsal, Dorsal and Sacral vertebrae of Titanosauria (Sauropod Dinosaurs) discovered from the Latest Cretaceous Dinosaur beds/Vitakri Member of Pab Formation, Sulaiman Foldbelt, Pakistan. Jour.Appl. Emer.Sci. 1(3), 188-196. Malkani M.S. 2006c. Lithofacies and Lateral extension of Latest Cretaceous Dinosaur beds from Sulaiman foldbelt, Pakistan. Sindh University Research Journal (Science Series) 38 (1), 1-32. Malkani M.S. 2007a. Trackways evidence of sauropod dinosaurs confronted by a theropod found from Middle Jurassic Samana Suk Limestone of Pakistan. Sindh University Research Journal (Science Series) 39 (1), 1-14. Malkani M.S. 2007b. Cretaceous Geology and dinosaurs from terrestrial strata of Pakistan. In abstract volume of 2nd International Symposium of IGCP 507 on Paleoclimates in Asia during the Cretaceous: theirvariations, causes, and biotic and environmental responses, Seoul, Korea, 57-63. Malkani M.S. 2007c. Lateral and vertical rapid variable Cretaceous depositional environments and Terrestrial dinosaurs from Pakistan. In abstracts volume of IGCP 555 on Joint Workshop on Rapid Environmental/Climate Change in Cretaceous Greenhouse World: Ocean-Land Interaction and Deep Terrestrial Scientific Drilling Project of the Cretaceous Songliao Basin, Daqing, China, Cretaceous World-Publication, 44-47. Malkani M.S., 2007d. First diagnostic fossils of Late Cretaceous Crocodyliform (Mesoeucrocodylia, Reptilia) from Vitakri area, Barkhan District, Balochistan, Pakistan. In; Ashraf, M., Hussain, S. S., and Akbar, H. D. eds. Contribution to Geology of Pakistan 2007, Proceedings of 5th Pakistan Geological Congress 2004, A Publication of National Geological Society of Pakistan, Pakistan Museum of Natural History, Islamabad, Pakistan, 241-259. Malkani M.S. 2007e. Paleobiogeographic implications of titanosaurian sauropod and abelisaurian theropod dinosaurs from Pakistan. Sindh University Research Journal (Science Ser.) 39 (2), 33-54. 49 Malkani M.S. 2008a. Marisaurus (Balochisauridae, Titanosauria) remains from the latest Cretaceous of Pakistan. Sindh University Research Journal (Science Series), 40 (2), 55-78. Malkani M.S. 2008b. First articulated Atlas-axis complex of Titanosauria (Sauropoda, Dinosauria) uncovered from the latest Cretaceous Vitakri member (Dinosaur beds) of upper Pab Formation, Kinwa locality of Sulaiman Basin, Pakistan. Sindh University Research Journal (Science Series) 40 (1), 55-70. Malkani M.S. 2008c. Mesozoic terrestrial ecosystem from Pakistan. In Abstracts of the 33rd International Geological Congress, (Theme HPF-14 Major events in the evolution of terrestrial biota, Abstract no. 1137099), Oslo, Norway, 1. Malkani M.S. 2008d. Titanosaur (Dinosauria, Sauropoda) osteoderms from Pakistan. . In abstract volume of the 3rd International Symposium of IGCP 507 on Paleoclimates in Asia during the Cretaceous: their variations, causes, and biotic and environmental responses, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia, 56-60. Malkani M.S. 2008e. Mesozoic Continental Vertebrate Community from Pakistan-An overview. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology Volume 28, Supplement to Number 3, 111A. Malkani M.S. 2009a. New Balochisaurus (Balochisauridae, Titanosauria, Sauropoda) and Vitakridrinda (Theropoda) remains from Pakistan. Sindh University Research Journal (Science Series), 41 (2), 65-92. Malkani M.S. 2009b. Terrestrial vertebrates from the Mesozoic of Pakistan. In abstract volume of 8th International Symposium on the Cretaceous System, University of Plymouth, UK, 49-50. Malkani M.S. 2009c. Basal (J/K) and upper (K/T) boundaries of Cretaceous System in Pakistan. In abstract volume of 8 th International Symposium on the Cretaceous System, University of Plymouth, UK, 58-59. Malkani M.S. 2009d. Cretaceous marine and continental fluvial deposits from Pakistan. In abstract volume of 8 th International Symposium on the Cretaceous System, University of Plymouth, UK, 59. Malkani M.S. 2009e. Dinosaur biota of the continental Mesozoic of Pakistan. In Proceedings of the 4th International Symposium of the IGCP 507 on Paleoclimates of the Cretaceous in Asia and their global correlation, Kumamoto University and Mifune Dinosaur Museum, Japan, 66-67. Malkani M.S. 2010a. Updated Stratigraphy and Mineral potential of Sulaiman (Middle Indus) basin, Pakistan. Sindh University Research Journal (Science Series). 42 (2), 39-66. Malkani M.S. 2010b. New Pakisaurus (Pakisauridae, Titanosauria, Sauropoda) remains, and Cretaceous Tertiary (K-T) boundary from Pakistan. Sindh University Research Journal (Science Series). 42 (1), 39-64. Malkani M.S. 2010c. Osteoderms of Pakisauridae and Balochisauridae (Titanosauria, Sauropoda, Dinosauria) in Pakistan. Journal of Earth Science, Vol. 21, Special Issue 3, 198-203; doi: 1007/s12583-010-0212-z. Malkani M.S. 2010d. Pakisauridae and Balochisauridae Titanosaurian Sauropod Dinosaurs from the Non Marine Mesozoic of Pakistan. In Proceedings of the 5th Symposium of IGCP 507 on Paleoclimates of the Cretaceous in .Asia and their global correlation, October 7-8, Yogyakarta, Indonesia, extended abstract no 61, 13p. Malkani M.S. 2010e. Lithostratigraphy and Vertebrates from the Indus Basin of Pakistan. In Proceedings of the 5th Symposium of IGCP 507 on Paleoclimates of the Cretaceous in Asia and their global correlation, October 7-8, 2010, Yogyakarta, Indonesian, extended abstract no 65, 4p. Malkani M.S. 2010f. Dinosaurs and Cretaceous Tertiary (K-T) boundary of Pakistan-a big disaster alerts for present disaster advances. Proceeding volume of International Conference of Disaster Prevention Technology and Management (DPTM; Chongqing, China, October 23-25, Journal Disaster Advances 3 (4), 567-572. Malkani M.S. 2011a. Stratigraphy, Mineral Potential, Geological History and Paleobiogeography of Balochistan Province, Pakistan. Sindh University Research Journal (Science Series). 43 (2), 269-290. Malkani M.S. 2011b. Vitakridrinda and Vitakrisaurus of Vitakrisauridae theropoda from Pakistan. In Proceedings of the 6th Symposium of IGCP 507 on Paleoclimates of the Cretaceous in Asia and their global correlation, August 15-16, 2011, Beijing, China, 59-66. Malkani M.S. 2011c. Trackways: Confrontation Scenario among A Theropoda and A Herd of Wide Gauge Titanosaurian Sauropods from Middle Jurassic of Pakistan. In Proceedings of 6th Symp. of IGCP 507 on Paleoclimates of the Cretaceous in Asia and their global correlation, August 15-16, Beijing, China, 67-75. Malkani M.S. 2012a. A review of Coal and Water resources of Pakistan. Journal of “Science, Technology and Development” 31(3), 202-218. 50 Malkani M.S. 2012b. Discovery of fluorite deposits from Loralai District, Balochistan, Pakistan. Abstract Volume and Program, Earth Sciences Pakistan, Baragali Summer Campus, University of Peshawar, June 23-24, Pakistan, Journal of Himalayan Earth Sciences, 45 (2), 69. Malkani M.S. 2012c. Discovery of celestite deposits in the Sulaiman (Middle Indus) Basin, Balochistan, Pakistan. Abstract Volume and Program, Earth Sciences Pakistan, Baragali Summer Campus, University of Peshawar, June 23-24, Pakistan, Journal of Himalayan Earth Sciences, 45 (2), 68-69. Malkani M.S. 2012d. Natural Resources of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Gilgit-Baltistan and Azad Kashmir, Pakistan. Abstract Volume and Program, Earth Sciences Pakistan, Baragali Summer Campus, University of Peshawar, June 23-24, Pakistan, Journal of Himalayan Earth Sciences, 45 (2), 70. Malkani M.S. 2012e. A review on the mineral and coal resources of northern and southern Punjab, Pakistan. Abstract Volume and Program, Earth Sciences Pakistan, Baragali Summer Campus, University of Peshawar, June 23-24, Pakistan, Journal of Himalayan Earth Sciences, 45 (2), 67. Malkani M.S. 2012f. New Look of titanosaurs: Tail Special of Pakisauridae and Balochisauridae, Titanosauria from Pakistan. In abstract volume of 11th Symposium on “Mesozoic Terrestrial Ecosystems (MTE 2012), Biota and Ecosystem and their Global Correltion” August 15-18, Gwanju, Korea. Malkani M.S. 2012g. New Styles of locomotion: Less wide gauge movement in Balochisauridae and More Wide gauge movement in Pakisauridae (Titanosauria) of Pakistan. In abstract volume of 11 th Symposium on “Mesozoic Terrestrial Ecosystems (MTE 2012), Biota and Ecosystem and their Global Correltion” August 15-18, Gwanju, Korea. Malkani M.S. 2012h. Paleobiogeography and Wandering of Indo-Pakistan Subcontinent. In abstract volume of 11 th Symposium on “Mesozoic Terrestrial Ecosystems (MTE 2012), Biota and Ecosystem and their Global Correltion” August 15-18, Gwanju, Korea. Malkani M.S. 2012i. Paleobiogeography and first collision of Indo-Pakistan subcontinent with Asia. Abstract Volume and Program, Earth Sciences Pakistan, Baragali Summer Campus, University of Peshawar, June 23-24, Pakistan, Journal of Himalayan Earth Sciences, 45 (2), 71-72. Malkani M.S. 2012j. Biodiversity of Dinosaurs from the Mesozoic of Pakistan. In abstract volume of International Conference on “Climate Change: Opportunities and Challenges” May 9-11, 2012, Islamabad, Pakistan, 83-84. Malkani M.S. 2013a. Natural resources of Southern Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and FATA regions (Kohat sub-basin and part of northern Sulaiman Basin and Western Indus Suture), Pakistan-A review. Abstract Volume, Sustainable Utilization of Natural Resources of the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and FATA, February 11, Peshawar, Pakistan. Journal of Himalayan Earth Sciences, Special volume 2013, 3031. Malkani M.S. 2012k. Revised lithostratigraphy of Sulaiman and Kirthar Basins, Pakistan. Abstract Volume and Program, Earth Sciences Pakistan, Baragali Summer Campus, University of Peshawar, June 23-24, Pakistan, Journal of Himalayan Earth Sciences, 45 (2), 72. Malkani M.S. 2013b. Coal and petroleum resources of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and FATA (Pakistan)-An overview. Abstract, Sustainable utilization of Natural Resources of the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and FATA. Abstract Volume, Sustainable Utilization of Natural Resources of the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and FATA, February 11, Peshawar, Pakistan. Journal of Himalayan Earth Sciences, Special Volume 2013, 27-29. Malkani M.S. 2013c. New pterosaur from the latest Cretaceous Terrestrial Strata of Pakistan. In; Abstract Book of 9 th International Symposium on the Cretaceous System, September 1-5, Metu Congress Center, Ankara, Turkey, 62. Malkani M.S. 2013d. Dinosaurs and Crocodiles from the Cretaceous Terrestrial Ecosystem of Pakistan. In; Abstract Book of 9 th International Symposium on the Cretaceous System, September 1-5, Metu Congress Center, Ankara, Turkey, 114. Malkani M.S. 2013e. Geodynamics of Indo-Pakistan Subcontinent (South Asia). In; Abstract Book of 9 th International Symposium on the Cretaceous System, September 1-5, Metu Congress Center, Ankara, Turkey, 36. Malkani M.S. 2013f. Paleobiogeographic implications of Cretaceous dinosaurs and mesoeucrocodiles from Pakistan. In; Abstract Book of 9th International Symposium on the Cretaceous System, September 1-5, Metu Congress Center, Ankara, Turkey, 35. Malkani M.S. 2013g. Depositional environments of Cretaceous strata of Indus basin (Pakistan). In; Abstract Book of 9 th International Symposium on the Cretaceous System, September 1-5, Metu Congress Center, Ankara, Turkey, 66. Malkani M.S. 2013h. Major Bioevents and extinction of land vertebrates in Pakistan; Cretaceous-Tertiary and other boundaries. In; Abstract Book of 9th International Symposium on the Cretaceous System, September 1-5, Metu Congress Center, Ankara, Turkey, 44. 51 Malkani M.S. 2013i. Latest Cretaceous land vertebrates in Pakistan; a paradise and a graveyard. In; Abstract Book of 9th International Symposium on the Cretaceous System, September 1-5, Metu Congress Center, Ankara, Turkey, 41. Malkani M.S. 2014a. Mineral resources of Sindh Province, Pakistan. Abstract Volume, Earth Sciences Pakistan, Baragali Summer Campus, University of Peshawar, August 29-31, Pakistan, Journal of Himalayan Earth Sciences, abstract volume, 57-58. Malkani M.S. 2014b. Mineral and gemstone resources of Azad Kashmir and Gilgit-Baltistan (Pakistan). Abstract Volume, Earth Sciences Pakistan, Baragali Summer Campus, University of Peshawar, August 29-31, Pakistan, Journal of Himalayan Earth Sciences, abstract volume, 58-59. Malkani M.S. 2014b. Mineral and gemstone resources of Azad Kashmir and Gilgit-Baltistan (Pakistan). Abstract Volume, Earth Sciences Pakistan, Baragali Summer Campus, University of Peshawar, August 29-31, Pakistan, Journal of Himalayan Earth Sciences, abstract volume, 58-59. Malkani M.S. 2014c. Revised Stratigraphy of Balochistan Basin, Pakistan. Abstract Volume, Earth Sciences Pakistan, Baragali Summer Campus, University of Peshawar, August 29-31, Pakistan, Journal of Himalayan Earth Sciences, abstract volume, 59-60. Malkani M.S. 2014d. Titanosaurian sauropod dinosaurs from the Latest Cretaceous of Pakistan. In abstract volume; 2nd symposium of International Geoscience Program 608 (IGCP 608) “Cretaceous Ecosystem of Asia and Pacific” September 04-06, 2014, Tokyo, Japan, 108-111. Malkani M.S. 2014e. Theropod dinosaurs and mesoeucrocodiles from the Terminal Cretaceous of Pakistan. In abstract volume; 2nd Symposium of International Geoscience Program 608 (IGCP 608) “Cretaceous Ecosystem of Asia and Pacific” September 04-06, 2014, Tokyo, Japan, 169-172. Malkani M.S. 2014f. Records of fauna and flora from Pakistan; Evolution of Indo-Pakistan Peninsula. In abstract volume; 2nd symposium of International Geoscience Program 608 (IGCP 608) “Cretaceous Ecosystem of Asia and Pacific” September 04-06, 2014, Tokyo, Japan, 165-168. Malkani M.S. 2014g. Dinosaurs from the Jurassic and Cretaceous Systems of Pakistan: their Paleobiogeographic link. In Abstract Volume of 1st Symposium of IGCP 632 “Geologic and biotic events on the continent during the Jurassic/Cretaceous transition” and 4 th International Palaeontological Congress, September 28 to October 03, 2014, Mendoza, Argentina, 872. Malkani M.S. 2014h. Terrestrial Ecosystem from the Mesozoic Geopark of Pakistan. In Abstract Volume of 6th Symposium of UNESCO Conference on Global Geoparks, September 19-22, Stonehammer Geopark, Saint John, Canada, 56. Malkani M.S. 2015a. Mesozoic tectonics and Sedimentary Mineral Resources of Pakistan. In: Zhang Y., Wu S.Z., Sun G. eds., abstract volume, 12th Symposium on “Mesozoic Terrestrial Ecosystems (MTE 12), and 3 rd Symposium of International Geoscience Program (IGCP 608) “Cretaceous Ecosystem of Asia and Pacific”, August 15-20, 2015, Paleontological Museum of Liaoning/Shenyang Normal University, Shenyang, China, 261-266. Malkani M.S. 2015b. Geodiverse and biodiverse heritage of Pakistan demands for protection as national and global Geoparks: an innovation for the sustainable development of Pakistan. In: Zhang Y., Wu S.Z., Sun G. eds., abstract volume, 12 th Symposium on “Mesozoic Terrestrial Ecosystems (MTE 12) and 3 rd Symposium of International Geoscience Program (IGCP 608) “Cretaceous Ecosystem of Asia and Pacific” August 15-20, 2015, Paleontological Museum of Liaoning/Shenyang Normal University, Shenyang, China, 247-249. Malkani M.S. 2015c. Dinosaurs, mesoeucrocodiles, pterosaurs, new fauna and flora from Pakistan. Geological Survey of Pakistan, Information Release No. 823: i-iii,1-32 (Total 35 pages). Malkani M.S. 2015d. Titanosaurian sauropod dinosaurs from Pakistan. In: Zhang Y.,Wu S.Z., Sun G. eds., abstract volume, 12th Symposium on “Mesozoic Terrestrial Ecosystems (MTE 12), and 3 rd Symposium of International Geoscience Program (IGCP 608) “Cretaceous Ecosystem of Asia and Pacific” August 15-20, 2015, Paleontological Museum of Liaoning/Shenyang Normal University, Shenyang, China, 93-98 Malkani M.S. 2015e. Footprints and trackways of dinosaurs from Indo-Pakistan Subcontinent-Recent Advances in discoveries from Pakistan. In: Zhang Y., Wu S.Z., Sun G. eds., abstract volume, 12th Symposium on “Mesozoic Terrestrial Ecosystems (MTE 12), and 3rd Symposium of International Geoscience Program (IGCP 608) “Cretaceous Ecosystem of Asia and Pacific” August 15-20, 2015, Paleontological Museum of Liaoning/Shenyang Normal University, Shenyang, China, 186-191. Malkani M.S. 2015f. First Trackways of Titanosaurian sauropod dinosaurs from Asia found from the Latest Cretaceous of Pakistan: Recent Advances in discoveries of dinosaur trackways from South Asia. In abstract volume of 2nd Symposium of IGCP 632 “Geologic and biotic events on the Continent during Jurassic/Cretaceous transition” September 12-13, 2015, Shenyang, China,86-88. Malkani M.S. 2015g. Osteoderms and dermal plates of titanosaurian sauropod dinosaurs found from Pakistan; Reported first time in Asia. In: Zhang Y., Wu S.Z., Sun G. eds., abstract volume, 12th Symposium on “Mesozoic Terrestrial Ecosystems (MTE 12), and 3 rd Symposium of International Geoscience Program (IGCP 608) “Cretaceous Ecosystem of Asia and Pacific” August 15-20, 2015, Paleontological Museum of Liaoning/Shenyang Normal University, Shenyang, China, 250-254. 52 Malkani M.S. 2015h. Titanosaurian (Sauropoda, Dinosauria) Osteoderms: First Reports from Asia. In abstract volume, 2nd Symposium of IGCP 632 “Geologic and biotic events on the continent during the Jurassic/Cretaceous transition” September 12-13, 2015, Shenyang, China, 82-85. Malkani M.S. 2016a. New Coalfields of Balochistan, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, FATA and Azad Kashmir. Abstract Volume, Qazi, M.S., Ali, W. eds., International Conference on Sustainable Utilization of Natural Resources, October 03, National Centre of Excellence in Geology, University of Peshawar, Peshawar, Pakistan. Journal of Himalayan Earth Sciences, 53-54. Malkani M.S. 2016b. Petroleum and construction stone resources of Balochistan, Sulaiman and Kirthar basins (Pakistan). Abstract Volume, Earth Sciences Pakistan 2016, 15-17 July, Baragali Summer Campus, University of Peshawar, Pakistan, Journal of Himalayan Earth Sciences, 104. Malkani M.S. 2016c. Vitakri Dome of Pakistan-a richest graveyard of Titanosaurian Sauropod Dinosaurs and Mesoeucrocodiles in Asia. In: Dzyuba, O.S., Pestchevitskaya, E.B., and Shurygin, B.N. Eds., (ISBN 978-5-4262-0073-9) Cretaceous Ecosystems and Their Responses to Paleoenvironmental Changes in Asia and the Western Pacific: Short papers for the Fourth International Symposium of International Geoscience Programme IGCP Project 608, August 15-20, 2016, Trofimuk Institute of Petroleum Geology and Geophysics, Siberian Branch, Russian Academy of Science (IPGG SB RAS), Novosibirsk, Russia, 129-132. Malkani M.S. 2016d. Revised stratigraphy of Indus Basin (Pakistan): Sea level changes. In: Dzyuba, O.S., Pestchevitskaya, E.B., and Shurygin, B.N. Eds., (ISBN 978-5-4262-0073-9) Cretaceous Ecosystems and Their Responses to Paleoenvironmental Changes in Asia and the Western Pacific: Short papers for the Fourth International Symposium of International Geoscience Programme IGCP Project 608, August 15-20, 2016, Trofimuk Institute of Petroleum Geology and Geophysics, Siberian Branch, Russian Academy of Science (IPGG SB RAS), Novosibirsk, Russia, 96-99. Malkani M.S. 2016e. Pakistan Paleoclimate under greenhouse conditions; Closure of Tethys from Pakistan; Geobiological evolution of South Asia (Indo-Pak subcontinent). In: Dzyuba, O.S., Pestchevitskaya, E.B., and Shurygin, B.N. Eds., (ISBN 978-5-4262-0073-9) Cretaceous Ecosystems and Their Responses to Paleoenvironmental Changes in Asia and the Western Pacific: Short papers for the Fourth International Symposium of International Geoscience Programme IGCP Project 608, August 15-20, 2016, Trofimuk Institute of Petroleum Geology and Geophysics, Siberian Branch, Russian Academy of Science (IPGG SB RAS), Novosibirsk, Russia, 59-61. Malkani M.S., Alyani M.I. Khosa M.H., Tariq S., Buzdar F.S., Khan G., Faiz J. 2016. Mineral Resources of Pakistan-an update. Lasbela University Journal of Science & Technology Volume 5, 90-114. Malkani M.S., Alyani M.I. Khosa M.H., Buzdar F.S., Zahid M.A. 2016. Coal resources of Pakistan; new coalfields. Lasbela University Journal of Science & Technology Volume 5, 7-22. Malkani M.S., Alyani M.I. Khosa M.H. 2016. New Fluorite and Celestite deposits from Pakistan: Tectonic and Sedimentary Mineral Resources of Indus Basin (Pakistan)-an overview. Lasbela University Journal of Science & Technology Volume 5, 27-33. Malkani M.S., Anwar C.M. 2000. Discovery of first dinosaur fossil in Pakistan, Barkhan District, Balochistan. Geological Survey of Pakistan Information Release 732: 1-16. Malkani M.S., Dhanotr M.S.I. 2014. New remains of giant Basilosauridae (Archaeoceti, Cetacea, Mammilia) and Giant baluchithere (Rhinocerotoidea, Perissodactyla, Mammalia) found from Pakistan. In Abstract Volume of 1st Symposium of IGCP 632 “Geologic and biotic events on the continent during the Jurassic/Cretaceous transition” and 4 th International Palaeontological Congress, September 28 to October 03, 2014, Mendoza, Argentina, 884. Malkani M.S., Dhanotr M. S. I., Latif A., Saeed, H. M., 2013. New remains of Basilosauridae-the giant basal whale, and baluchitherethe giant rhinoceros discovered from Balochistan Province (Pakistan). Sindh University Research Journal (Science Series). 45 (A-1), 177-188. Malkani M.S., Haq M. 1998. Discovery of pegmatite and associated plug in Tor Ghundi, Shabozai area, Loralai Distt., Balochistan. GSP, IR 668, 1-19. Malkani M.S., Mahmood Z. 2016a. Mineral Resources of Pakistan: A Review. Geological Survey of Pakistan, Record Volume 128: iiii, 1-90. Malkani M.S., Mahmood Z. 2016b. Revised Stratigraphy of Pakistan. Geological Survey of Pakistan, Record Volume 127: i-iii, 1-87. Malkani M.S., Mahmood Z. 2016c. Coal Resources of Pakistan: entry of new coalfields. Geological Survey of Pakistan, Information Release No. 981: 1-28. Malkani M.S., Mahmood Z. 2016d. Fluorite from Loralai-Mekhtar and Celestite from Barkhan, Dera Bugti, Kohlu, Loralai and Musakhel districts (Sulaiman Foldbelt) and Karkh area of Khuzdar district (Kirthar Range): a glimpse on Tectonic and Sedimentary Mineral Resources of Indus Basin (Pakistan). Geological Survey of Pakistan, Information Release No. 980: 1-16. 53 Malkani M.S., Mahmood Z. 2016e. Clay (ceramic) mineral resources of Pakistan: recent advances in discoveries. Abstract Volume, Earth Sciences Pakistan 2016, 15-17 July, Baragali Summer Campus, University of Peshawar, Pakistan, Journal of Himalayan Earth Sciences, 101. Malkani M.S., Mahmood Z. 2016f. Coal resources of Pakistan: new coalfields of Balochistan, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Azad Kashmir. Abstract Volume, Earth Sciences Pakistan 2016, 15-17July, Baragali Summer Campus, University of Peshawar, Pakistan, Journal of Himalayan Earth Sciences, 102. Malkani M.S., Mahmood Z. 2016g. Mineral Resources of Azad Kashmir and Hazara (Pakistan): special emphasis on Bagnotar-Kala Pani (Abbottabad, Hazara) new coalfield. Abstract Volume, Earth Sciences Pakistan 2016, 15-17July, Baragali Summer Campus, University of Peshawar, Pakistan, Journal of Himalayan Earth Sciences, 103. Malkani M.S., Mahmood Z. 2016h. Revised stratigraphy of uppermost Indus (Khyber-Hazara-Kashmir) basin, Pakistan. Abstract Volume, Earth Sciences Pakistan 2016, 15-17 July, Baragali Summer Campus, University of Peshawar, Pakistan, Journal of Himalayan Earth Sciences, 105. Malkani M.S., Mahmood Z.2017a. Stratigraphy of Pakistan. Geological Survey of Pakistan, Memoir Volume 24, 1-134. Malkani M.S., Mahmood Z.2017b. Mineral Resources of Pakistan: provinces and basins wise. Geological Survey of Pakistan, Memoir Volume 25, 1-179. Malkani M.S., Mahmood Z., Alyani M.I., Shaikh S.I. 2017a. Mineral Resources of Sindh. Geological Survey of Pakistan, Information Release 994: 1-38. Malkani M.S., Mahmood Z., Shaikh S.I., Alyani M.I. 2017b. Mineral Resources of north and south Punjab. Geological Survey of Pakistan, Information Release 995: 1-52. Malkani M.S., Mahmood Z., Alyani M.I., Siraj M. 2017c. Mineral Resources of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and FATA, Pakistan. Geological Survey of Pakistan, Information Release 996: 1-61. Malkani M.S., Mahmood Z., Usmani N.A., Siraj M. 2017d. Mineral Resources of Azad Kashmir and Gilgit-Baltistan, Pakistan. Geological Survey of Pakistan, Information Release 997: 1-40. Malkani M.S., Mahmood Z., Shaikh S.I., Arif S.J. 2017e. Mineral Resources of Balochistan Province, Pakistan. Geological Survey of Pakistan, Information Release (GSP IR) No. 1001: 1-43. Malkani M.S., Mahmood Z., Arif S.J., Alyani M.I. 2017f. Revised Stratigraphy and Mineral Resources of Balochistan Basin, Pakistan. Geological Survey of Pakistan, Information Release (GSP IR) No. 1002: 1-38. Malkani M.S., Mahmood Z., Alyani M.I., Shaikh S.I. 2017g. Revised Stratigraphy and Mineral Resources of Sulaiman Basin, Pakistan. Geological Survey of Pakistan, Information Release (GSP IR) No. 1003: 1-63. Malkani M.S., Mahmood Z., Somro N., Arif S.J. 2017h. Gemstone and Jewelry Resources of Pakistan, Gilgit-Baltistan and Azad Kashmir. Geological Survey of Pakistan, Information Release (GSP IR) No. 1004: 1-28. Malkani M.S., Mahmood Z., Somro N., Alyani M.I. 2017i. Cement Resources, Agrominerals, Marble, Construction, Dimension and Decorative Stone Resources of Pakistan, GSP, IR No. 1005: 1-23. Malkani M.S., Qazi S., Mahmood Z., Khosa M.H., Shah M.R., Pasha A.R., Alyani M.I. 2016. Agromineral Resources of Pakistan: an urgent need for further sustainable development. Abstract Volume, Qazi, M.S., Ali, W. eds. International Conference on Sustainable Utilization of Natural Resources, October 03, National Centre of Excellence in Geology, University of Peshawar, Peshawar, Pakistan. Journal of Himalayan Earth Sciences, 51-52. Malkani M.S., Sajjad A. 2012. Coal of Shirani Area, D.I. Khan District, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. Abstract Volume and Program, Earth Sciences Pakistan, Baragali Summer Campus, University of Peshawar, June 23-24, Pakistan, Journal of Himalayan Earth Sciences, 45 (2), 73-74. Malkani M. S., Shah M.R. 2016. Chamalang coal resources and their depositional environments, Balochistan, Pakistan. Geological Survey of Pakistan, Information Release No. 969:13p. Malkani M.S., Shah M.R. 2014. Chamalang coal resources and their depositional environments, Balochistan, Pakistan. Journal of Himalayan Earth Sciences, 47(1), 61-72. Malkani M.S., Shah M.R., Bhutta A.M. 2007. Discovery of Flourite deposits from Mula-Zahri Range of Northern Kirthar Fold Belt, Khuzdar District, Balochistan, Pakistan. In; Ashraf, M., Hussain, S.S. and Akbar, H.D. eds. Contribution to Geology of Pakistan 2007, Proceedings of 5th Pakistan Geological Congress 2004, A Publication of the National Geological Society of Pakistan, Pakistan Museum of Natural History, Islamabad, Pakistan, 285-295. 54 Malkani M.S., Shah M.R., Sajjad A., Kakepoto A.A., Haroon Y. 2013. Mineral and Gemstone Resources of Northern Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and FATA regions, Pakistan-A good hope. Abstract Volume, Sustainable Utilization of Natural Resources of the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and FATA, February 11, Peshawar, Pakistan. Journal of Himalayan Earth Sciences, Special Volume 2013, 2526. Malkani M.S., Shahzad A., Umar M., Munir H., Sarfraz Y., Umar M., Mehmood A. 2016. Lithostratigraphy, structure and economic geology of Abbottabad-Nathiagali-Kuldana-Murree road section, Abbottabad and Rawalpindi districts, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Punjab provinces, Pakistan. Abstract Volume, Earth Sciences Pakistan 2016, 15-17 July, Baragali Summer Campus, University of Peshawar, Pakistan, Journal of Himalayan Earth Sciences, 168. Malkani M.S., Sun G. 2016. Fossil biotas from Pakistan with focus on dinosaur distributions and discussion on paleobiogeographic evolution of Indo-Pak Peninsula. Proceeding volume of 12th Symposium on “Mesozoic Terrestrial Ecosystems (MTE-12) and 3rd Symposium of International Geoscience Program (IGCP 608) “Cretaceous Ecosystem of Asia and Pacific” August 15-20, 2015, Paleontological Museum of Liaoning/Shenyang Normal University, Shenyang, China, Global Geology 19 (4), 230-240. Article ID: 1673-9736 (2016) 04-0230-11: Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10. 3936/j. issn. 1673-9736. 2016. 04. 04. Malkani M.S., Tariq M. 2000. Barite Mineralization in Mekhtar area, Loralai District, Balochistan, Pakistan, GSP IR 672, 1-9. Malkani M.S., Tariq M. 2004. Discovery of barite deposits from the Mekhtar area, Loralai District, Balochistan, Pakistan. In abstract volume National Conference on Economic and Environmental sustainability of Mineral resources of Pakistan,Baragali, Pakistan, 48. Malkani M.S., Wilson J.A., Gingerich P.D. 2001. First Dinosaurs from Pakistan. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology (USA), Volume 21(3): 77A. Marivaux L, Welcomme J.L., Antoine P.O., Metais G., Baloch I.M., Benammi M., Chaimanee Y., Ducrocq S., Jaeger J. J. 2001. A Fossil Lemur from the Oligocene of Pakistan. Science, 294 (5542): 587-591. Marks P. 1962. Variation and evolution in orbitoides of the Cretaceous of Rakhi Nala, West Pakistan. Geol. Bull. Punjab university, 2:15-29. Master J.M. et al. 1952. A note on Manganese ore in Lasbela. GSP file 541(8), 4p. Master J.M. 1963. Limestone resources of West Pakistan. In Symp. Lahore, 189-198. Master J.M. 1960. Manganese showings of Las Bela district, Pakistan. GSP, IR 13, 16p. Metais G., Antoine P-O., Baqri S.R.H., Benammi M., Crochet J.-Y., Franceschi D. de, Marivaux L., Welcomme J.-L. 2006. New remains of the enigmatic cetartiodactyl Bugtitherium grandincisivum Pilgrim 1908, from the upper Oligocene of the Bugti Hills (Balochistan, Pakistan). Nature 97(7), 348-355. Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Resources 2009. Pakistan Energy Yearbook 2008, Hydrocarbon Development Institute of Pakistan, Islamabad. Moghal M.Y., Baig M.A., Syed S.A. 1997. Siwalik group: A potential host for uranium. 3 rd Geosas workshop on Siwalik of South Asia, Islamababd, Abstracts 38p. Mohsin S.I., Sarwar G. 1974. Geology of Dilband fluorite deposits. Geonews 4, 24-30. Mohsin S.I., Sarwar D., Farooqi M.A. 1981. Geology of Gachero Dhoro barite deposit, Las Bela, Pakistan. Acta MineralogicaPetrographica 5, 25, Szsged (Hungry). Mohsin S.I., Farooqi M.A., Qaudri M.U. 1983. Distribution and controls of barite-fluorite-sulphide mineralization in Kirthar-Sulaiman fold belt, Pakistan. Acta Univ. Carolina Geologica 3, 237-249. Moosvi A.T. 1973. Celestite mineralization in Surgan anticline, Thano Bula Khan, District Dadu. GSP, Geonews 3, 34-35. Muller C. 2002. Nannoplanktonic biostratigraphy of the Kirthar and Sulaiman ranges, Pakistan. Geol. Bull. Peshawar Univ. 14: 73-84. Muslim M. 1971. Evaluation of sulphur deposits, Koh-i-Sultan (dist. Chagai). GSP, Rec. 21(2); 8p. Muslim M. 1973a. The evaluation of Sanni sulphur deposits, Kachi District, Kalat, (Balochistan). GSP, Rec. 21(2): 8p. Muslim M. 1973b. The evaluation of sulphur deposits of Koh-e-Sulatn, District Chagai (Baluchistan). Muslim M., Khan R.A. 1995. Geology of Nagarparker massif, Sindh. GSP IR 605, 117. Nagappa Y. 1951. Stratigraphic value of Miscellania and Pellatispira in India, Pakistan, Balochistan. Ibid., Rec. 55 Nagappa Y. 1959. Foraminiferal biostratigraphy of the Cretaceous-Eocene succession in India, Pakistan, Burma regions. Micropaleotology vol. 5, 145-179. Nagappa Y. 1959. The Cretaceous-Tertiary boundary in Indian Pakistan subcontinent. Internat. Geol. Cong. 21 st session rep. Copenhagen, pt. 5, 41-49. Nagell R.H. 1969. Sulphur, fluorspar, magnesite and aluminous chromite deposits in west Pakistan. USGS, pk-49:33p. Nasim S. 1996. The genesis of manganese ore deposits of Las Bela, Balochistan, Pakistan. Ph.D. thesis, Geology Dept. Karachi Univ. 262p. Noetling F. 1894. On the Cambrian formation of eastern Salt range. Geol. Surv. India Rec. vol. 27, pt. 4, 71-86. Noetling F. 1895. Balochistan fossils; Part I, the fauna of the Kellaways of Mazar Drik. Ibid., Mem. Paleont. Indica ser. 16, vol. 1, pt. 1, 1-22. Nuttall W.L.F. 1925. The stratigraphy of the Laki series (lower Eocene) of part of Sind and Balochistan with a description of larger foraminifera contained in those beds. Geol. Soc. London Quart. Journ. 81, 417-453. Nuttall W.L.F. 1926. The zonal distribution of larger foraminifera of the Eocene of Western India. Geol. Mag. Vol. 63, 495-504. Nuttall W.L.F. 1931. The stratigraphy of the upper Ranikot (lower Eocene) of Sind. Geol. Surv.India, Rec. 65, 306-313. Oldham R.D. 1890. Report on geology and economic resources of the country adjoining the Sind-Pishin railway between Sharig and Spin Tangi and country between it and Khattan. GSI, Rec. 23,pt3, 93-110. Oldham T. 1890. Proceedings of the Asiatic Society of Bengal for July, 1860; Asiatic Soc. Bengal Jour. 29 (3), 318-319. Owen R. 1842. Report on British fossil reptiles Pt. II. Rept. Br. Assoc. adv. Sci. 11:60-204. Pascoe E.H. 1923. General report for 1922. Geol. Surv. India, Rec. 55(1), 1-51. Pascoe E.H. 1950-1964. A manual of geology of India and Burma. 1950, v 1, 1959 v2, 1964 v3, Govt India press, Calcutta, 1-2130. Pascoe E.H. 1959. Manual of geology India and Burma Vol. ii India Govt press Calcutta 484-1338. Pilgrim G.E. 1908. The Tertiary and Post Tertiary fresh water deposits of Balochistan and Sind with notices of new vertebrates. India Geol. Surv. Recs. Vol. 37, pt 2, p. 139-166. Pilgrim G.E. 1912. The vertebrate fauna of the Gaj Series in the Dera Bugti Hills and Punjab. Geol. Surv. India, Mem. Paleont. Indica, New Ser. 2, Mem. Vol.4, 839. Pinfold E.S. 1939. The Dungan limestone and the Cretaceous-Eocene unconformity in the Northwest India. Geol. Surv. India Rec. 74(2):189-198. Powell Duffryn Technical services Ltd. 1949. Report on production and utilization of coal in Pakistan. Report to govt of Pakistan. Raza H.A., Iqbal M.W.A. 1977. Mineral deposits. In: Stratigraphy of Pakistan, (Shah, S.M.I., ed.), GSP, Memoir, 12, 98-120. Raza S.M., Meyer G.E. 1984. Early Miocene geology and paleontology of the Bugti hills, Pakistan. In: (Shah, S.M.I and D. Pilbeam, eds) Contribution to the Geology of Pakistan. Geol. Surv. Pakistan, Mem. 11, 43-63. Raza S.M, Cheema I.U., William R.D., Rajppar A.R., Ward S.C. 2002. Miocene stratigraphy and mammal fauna from the sulaiman Range, southwest Himalayas, Pakistan. Paleogeography, Paleosedimentology, Paleoecology, 186, 185-197. Raza S.M., Khan S.H., Karim T., Ali M. 2001. Stratigraphic Chart of Pakistan, published by Geological Survey of Pakistan. Rafiq M., Tariq J.A., Ahmad M. Akram W., Rafiq M., Iqbal N. 2004. Isotopic and geochemical investigation of geothermal resources in Pakistan. In abstract volume National Conference on Economic and Environmental sustainability of Mineral resources of Paki stan, Baragali, Pakistan, 53. Raza H.A., Iqbal M.W.A. 1977. Mineral deposits. In: Stratigraphy of Pakistan, (Shah, S.M.I., ed.), GSP, Memoir, 12, 98-120. Raza H.A., Ahmed R. 1990. Hydrocarbon potential of Pakistan. Journ. Canada-Pakistan cooperation 4 (1), 9-27. Raza H.A. Ahmed R., Ali S.M., Ahmad J. 1989c. Petroleum propects; Sulaiman sub-basin, Pakistan. Pak. J. Hydrocarbon Res. 1(2), 21-56. 56 Raza H.A. Ahmed R., Alam S., Ali S.M. 1989b. Petroleum zones of Pakistan. Pak. J. Hydrocarbon Res. 1(2), 1-19. Raza H.A. Ahmed R., Ali S.M., Sheikh A.M., Shafiwue N.A. 1989a. Exploration performance in sedimentary zones of Pakistan. Pak. J. Hydrocarbon Res. 1(1), 1-7. Raza H.A., Iqbal M.W.I. 1977. Mineral deposits. In Shah, S.M.I. (ed.) Stratigraphy of Pakistan. GSP, Mem. 12: 98-120. Raza S.M, Cheema I.U., William R.D., Rajppar A.R., Ward S.C. 2002. Miocene stratigraphy and mammal fauna from the sulaiman Range, southwest Himalayas, Pakistan. Paleogeography, Paleosedimentology, Paleoecology, 186, 185-197. Raza S.M., Khan S.H., Karim T., Ali M. 2001. Stratigraphic Chart of Pakistan, published by Geological Survey of Pakistan. Raza S.M., Meyer G.E. 1984. Early Miocene geology and paleontology of the Bugti hills, Pakistan. In: (Shah, S.M.I and D. Pilbeam, eds) Contribution to the Geology of Pakistan. Geol. Surv. Pakistan, Mem. 11, 43-63. Read H.H., 1953. Rutleys elements of mineralogy, Thomas Murby and co. London, 525p. Rizvi S.M.N. 1951. Manganese deposits of Lasbela. GSP file, 16p. Rizvi S.M.N. 1955. Mineral resources of Khairpur. GSP file 252, 6p. Roonwal G.S. 1986. The Indian ocean exploitable mineral and petroleum resources. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg New York London Paris Tokyo, printed in Germany, 198p. Sahni A. 2001. Dinosaurs of India. National book Trust, Delhi, 110pp. Sahni B. 1945. Micro-fossils and problems of Salt Range geology. Natl. Acad. Sci. India Proc. Sec. vol. 14, pt. 6, 1-30. Samanta B.K. 1973. Planktonic foraminifers from the Paleocene-Eocene succession in the Rakhi Nala, Sulaiman Range, Pakistan. Bull. British Museum (Natural History) Geology 22’ 421-482. Samini S.J., Rehman O., Haneef M. 2004. Paleogen biostratigraphy of Kohat area, North Pakistan. In abstract volume National Conference on Economic and Environmental sustainability of Mineral resources of Pakistan, Baragali, Pakistan, 58. Sarwar G. 1992. Tectonic setting of the Bela ophiolites, southern Pakistan. Tectonophysics 207, 358-381. Schweinfurth S.P., Hussain F. 1988. Coal resources of Lakhra and Sonda coalfields, Sindh, Pakistan. GSP, project report, IR, PK-82, pt.1, 36p. Searle M.P et al. 1987. The closing of Tethys and the Tectonics of the Himalay. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 98, 678-701. Seeley H.G. 1888. The classification of the Dinosauria. Brit. Assoc. Adv. Sci., Report. 1887: 698-699. Shah A.A., Khan S.A., Tagar M.A., Chandio A.H., Lashari G.S. 1992. Drilling and coal resources assessment in south Sindh. GSP, IR 537, 1-40. Shah M.R. 2001. Paleoenvironments, sedimentology and economic aspects of the Paleocene Hangu Formation in Kohat-Potwar and Hazara area. Ph.D thesis, University of Peshawar, Peshawar, 208 Pp. Shah M.R., Malkani M.S. 2016. Geodynamic and tectonic evolution of Indo-Pakistan peninsula (South Asia). Abstract Volume, Earth Sciences Pakistan 2016, 15-17 July, Baragali Summer Campus, Univ. Peshawar, Pakistan, Journal of Himalayan Earth Sciences, 148. Shah S.F.A., Naseer A., Tanoli M.A., Alami B. 2012. Viable use of rubber waste in concrete to reduce environmental pollution. Abstract Volume and Program, Earth Sciences Pakistan, Baragali Summer Campus, University of Peshawar, June 23-24, Pakistan, Journal of Himalayan Earth Sciences, 45 (2), 95. Shah S.M.I. 2002. Lithostratigraphic units of the Sulaiman and Kirthar provinces, Lower Indus Basin, Pakistan. GSP, Record 107, 63p. Shah S.M.I. 2009. Stratigraphy of Pakistan. Geol. Surv. Pakistan, Memoir 22, 381p. Shah S.M.I., Arif M. 1992. A description of Bugtitherium grandincisivam (Mammalia) of the bugti hills, Balochistan, Pakistan. Memoirs, Geol. Surv. Pakistan, Vol. 7, pt. III, 27-38. Shahzad A., Malkani M.S., Umer M., Munir M.H., Sarfraz Y., Shah M.R., Bukhari S.A.A., Nisar U.B. 2016. Construction stone resources of Muzaffarabad area, Azad Kashmir, Pakistan: special emphasis on bed rock resources. Abstract Volume, Earth Sciences Pakistan 2016, 15-17 July, Baragali Summer Campus, University of Peshawar, Pakistan, Journal of Himalayan Earth Sciences, 145. 57 Shahzad A., Malkani M.S., Shah M.R., Bokhari S.A.A., Nisar U.B. 2016. Geodisaster and lithostratigraphy of doubly plunging thrusted Muzafarabad anticline, Muzaffarabad District, Sub Himalayas, Azad Kashmir, Pakistan. Abstract Volume, Earth Sciences Pakistan 2016, 15-17 July, Baragali Summer Campus, University of Peshawar, Pakistan, Journal of Himalayan Earth Sciences, 147. Siddiqui, S, Jamiluddin, I.H. Qureshi and A.H. Kidwai (1965) Geol. map of degree sheet 39 J (GSP, unpubl.). Sohn I.G. 1959. Early Tertiary ostracodes from west Pakistan. Geol. Surv. Pakistan, Mem., Paleont. Pakistanika, vol. 3, no. 1, 78p. Shams F.A. 1995. Metallic raw materials. In; Bender and Raza (eds) Geology of Pakistan. Gebruder Borntraeger, 234-257. Shcheglov A.D. 1969. Main feature of endogenous Metallogeny of the southern parts of west Pakistan. GSP, Mem. 7: 12p. Shaikh S.I., Malkani M.S., Somro N., Jahangir A., Alyani M.I., Arif S.J. 2016. Stratigraphy and economic geology of Dhana SarMughal Kot-Domanda-Chaudhwan section, Zhob and D.I.Khan districts, Balochistan and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa provinces, Pakistan. Abstract Volume, Earth Sciences Pakistan 2016, 15-17 July, Baragali Summer Campus, University of Peshawar, Pakistan, Journal of Himalayan Earth Sciences, 146. Shcheglov A.D. 1969. Main feature of endogenous Metallogeny of the southern parts of west Pakistan. GSP, Mem. 7: 12p. Sheikh G.M. 1972. Evaluation of gypsum resources in Spintangi area, Sibi distt, Balochistan, Pakistan. GSP-IR 52, 1Siddiqui I. 2007. Environmental impact assessment of Thar, Sonda and Meting-Jhimpir coalfields of Sindh. J. Chem. Soc. Pak., 29, 3. Siddiqui I.U. 2004. Exploitation of economic minerals in Sindh, Pakistan: A threat to the environment. In abstract volume National Conference on Economic and Environmental sustainability of Mineral resources of Pakistan, Baragali, Pakistan, 63. Siddiqui N.K. 2004. The toil for oil-a global scenario. In abstract volume National Conference on Economic and Environmental sustainability of Mineral resources of Pakistan, Baragali, Pakistan, 64. Siddiqi R.H., Haider N., Abbas S.G., Kakepoto A.A. 2000. Mineralogy and genesis of Dilband Iron ore, Balochistan, Pakistan. Geologica 5, 67-97. Siddiqui S, Jamiluddin, Qureshi I.H., Kidwai A.H. 1965. Geological map of degree sheet 39 J (GSP, unpubl.). Sillitoe R.H. 1975. Metallogenic evolution of a collisional mountain belt in Pakistan. GSP, Record 34, 16p. Sillitoe R.H. 1979. Specul. on Himalayan Metallogeny on evidence from Pakistan. In Farah and DeJong (eds) Geodynamics of Pakistan. GSP, Quetta, 167-179. Somro N., Malkani M.S., Zafar T. 2016. Evaluation of Kunhar River Aggregate as a Construction Material, District Mansehra Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. Abstract Volume, Earth Sciences Pakistan 2016, 15-17 July, Baragali Summer Campus, University of Peshawar, Pakistan, Journal of Himalayan Earth Sciences, 151. Somro N., Malkani M.S., Zafar T., Alyani M.I., Khosa M.H., Mahmood Z. 2016. Stratigraphy and economic geology of Kaha-Harand section of Mari anticline, Rajan Pur District, Punjab, Pakistan. Abstract Volume, Qazi, M.S., Ali, W. eds., International Conference on Sustainable Utilization of Natural Resources, October 03, National Centre of Excellence in Geology, University of Peshawar, Peshawar, Pakistan. Journal of Himalayan Earth Sciences, 20. Stanin S.A., Hasan, M.S. 1966. Recon. For phosphate in west Pakistan. GSP, IR 32,17p. Subhani A.M., Durezai M.I. 1989. A note on the Surmai lead-zinc prospect, District Khuzdar, Balochistan. GSP, unpublished report. Tabbutt K.K., Sheikh A., Noye M. Johnson, 1997. A fission track age from the Bugti bone beds, Balochistan, Pakistan. Abs. Geol. Surv. Rec. Vol. 109. Tainsh H.R., Stringer K.V., Azad J. 1959. Major gas fields of West Pakistan: Amer. Assoc. Petroleum Geol. Bull. 43 (11), 2675-2700. Thangani G.Q, Haq M., Bhatti M.A. 2006. Preliminary report on occurrence of coal in Eocene Domanda Formation, in the Eastern Sulaiman Range, D.G.Khan area, Punjab, Pakistan. GSP, IR 833, 1-21. Tipper G.H. 1909. Minerals from Balochistan. GSI, Rec. 38, 214-215. Tainsh H.R., Stringer K.V., Azad J. 1959. Major gas fields of West Pakistan: Amer. Assoc. Petroleum Geol. Bull. 43 (11): 2675-2700. Teichert C., Stauffer K.W. 1965. Paleozoic reef discovery in Pakistan. Geol. Surv. PakistanRrec. vol. 14, 3p. 58 UNDTCD 1990. Exploration of the zinc-lead potential of the Las Bela-Khuzdar be;t, united nations, department of technical cooperation for development, Dp/UN/Pak-84-009/1; 26p. Vredenburg E.W. 1901 A geological sketch of the Baluchistan desert and part of eastern Persia. Geol. Surv. India, Mem. 31: 179-302. Vredenburg E.W. 1906. The classification of the Tertiary system in Sind with reference to the zone distribution of the Eocene Echinoidea described by Duncan and Sladen: India Geol. Survey Recs. 34, pt. 3, 172-198. Vredenburg E.W. 1908. The Cretaceous Orbitoides of India.Ibid Recs. Vol. 36, 171-213. Vredenburg E.W. 1909a. Mollusca of Ranikot series, introductory note on the stratigraphy of Ranikot series. Ibid., Mem. Paleont. Indica new series vol. 3, no.1, 5-19. Vredenburg E.W. 1909b. Report on the geology of Sarawan, Jhalawan, Makran and the state of Lasbela. Ibid., Rec. vol. 38,, pt. 3, 189-215. Van Vloten R. 1963. Magnesite in Pakistan. In Symp. Lahore 211-215. Vicary N. 1846. Geological report on a portion of the Baluchistan hills. Geol. Soc. London Quaternary journal 2, 260-267. Vredenburg E. 1901. A geological sketch of Balochistan desert and part of eastern Persia. GSI Mem. 31, 179-302. Vredenburg E.W. 1906. The classification of the Tertiary system in Sind with reference to the zone distribution of the Eocene Echinoidea described by Duncan and Sladen: India Geol. Survey Recs. 34, pt. 3, 172-198. Vredenburg E.W. 1907. Note on the occurrence of Physa prinsepii in the Maastrichtian strata of Balochistan. India Geol. Survey Recs. 35 (2), 114-118. Vredenburg E.W. 1909. Report on the geology of Sarawan, Jhalawan, Makran and the state os Lasbela. Geol. Survey India Recs. 38(3), 189-215. Wadia D.N. 1975. Geology of India. 3rd edition (revised). Macmillan, London, 531p. Wager L.R. 1939. The Lachi Series of N. Sikkim and the age of the rocks forming Mount everest. Geol. Surv. India, Recs, Vol. 74 (2): 171-188. Waheed A., Wells N.A. 1992. Changes in paleocurrents during the development of an obliquely convergence plate boundary, Sulaiman foldbelt, southwestern Himalaya, west central Pakistan. Sediment. Geol. 67, 237-261. West Pakistan Industrial development corporation (WPIDC). 1970c. Mineral resources of Balochistan Province. Unpub. Report, 138p. West Pakistan Industrial development corporation (WPIDC). 1970d. Mineral resources of Sindh Province. Unpub. Report, 199p. Whetstone K.N., Whybrow P.J. 1983. A cursorial crocodilian from the Triassic of Lesotho (Basutoland), South Africa. Occassional papers of the Museum of Natural History, University of Kunsas, 106, 1-37. White M.G. undated. Copper, lead, zinc, antimony and arsenic in West Pakistan. GSP, Tech. Letter. Williams M.D. 1959. Stratigraphy of Lower Indus Basin, West Pakistan. World Petroleum Cong. 5th New York, Proc. Sec. 1, 277-394. Wilson J.A, Malkani M.S., Gingerich P.D. 2001. New Crocodyliform (Reptilia, Mesoeucrocodylia) form the upper Cretaceous Pab Formation of Vitakri, Balochistan (Pakistan), Contributions form the Museum of Paleontology, The University of Michigan, 30(12), 321-336. Wilson J.A, Malkani M.S., Gingerich P.D. 2005. A sauropod braincase from the Pab Formation (Upper Cretaceous, Maastrichtian) of Balochistan, Pakistan. Gondwana Geol. Mag., Spec. Vol., 8, 101-109. Wilson J.A. 2010. Greater India before the Himalayas; Dinosaur eating snakes. 3quarksdaily, March 08, 2010 Woodward J.E. 1959. Stratigraphy of the Jurassic system, Indus Basin. Stand. Vacuum Oil. Co. Unpublished report, 2-13. White M.G. undated. Copper, lead, zinc, antimony and arsenic in West Pakistan. GSP, Tech. Letter. Zamin B.,Khan S.A., Khan K., Alam B., Ashraf M. 2012. Grading of bentonite of some quarries in Pakistan. Abstract Volume, Earth Sciences Pakistan, Baragali Summer Campus, University of Peshawar, June 23-24, Pakistan, Journal of Himalayan Earth Sciences, 45 (2), 109. 59 View publication stats