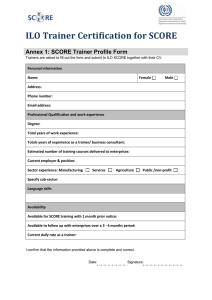

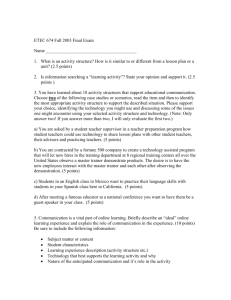

PERSONAL TRAINING QUARTERLY PTQ VOLUME VOLUME1 1 ISSUE ISSUE41 ABOUT THIS PUBLICATION Personal Training Quarterly (PTQ) publishes basic educational information for Associate and Professional Members of the NSCA specifically focusing on personal trainers and training enthusiasts. As a quarterly publication, this journal’s mission is to publish peer-reviewed articles that provide basic, practical information that is research-based and applicable to personal trainers. Copyright 2014 by the National Strength and Conditioning Association. All Rights Reserved. Disclaimer: The statements and comments in PTQ are those of the individual authors and contributors and not of the National Strength and Conditioning Association. The appearance of advertising in this journal does not constitute an endorsement for the quality or value of the product or service advertised, or of the claims made for it by its manufacturer or provider. PERSONAL TRAINING QUARTERLY PTQ VOLUME 1 ISSUE 4 EDITORIAL OFFICE EDITORIAL REVIEW PANEL EDITOR: Bret Contreras, MA, CSCS Scott Cheatham, DPT, PT, OCS, ATC, CSCS PUBLICATIONS DIRECTOR: Keith Cinea, MA, CSCS,*D, NSCA-CPT,*D MANAGING EDITOR: Matthew Sandstead, NSCA-CPT PUBLICATIONS COORDINATOR: Cody Urban Mike Rickett, MS, CSCS Andy Khamoui, MS, CSCS Josh West, MA, CSCS Scott Austin, MS, CSCS Nate Mosher, DPT, PT, CSCS, NSCA-CPT Laura Kobar, MS Leonardo Vando, MD Kelli Clark, DPT, MS Daniel Fosselman NSCA MISSION As the worldwide authority on strength and conditioning, we support and disseminate researchbased knowledge and its practical application, to improve athletic performance and fitness. Liz Kampschroeder TALK TO US… John Mullen, DPT, CSCS Ron Snarr, MED, CSCS Tony Poggiali, CSCS Chris Kennedy, CSCS Share your questions and comments. We want to hear from you. Write to Personal Training Quarterly (PTQ) at NSCA Publications, 1885 Bob Johnson Drive, Colorado Springs, CO 80906, or send an email to matthew.sandstead@nsca.com. Teresa Merrick, PHD, CSCS, NSCA-CPT Ramsey Nijem, MS, CSCS CONTACT Personal Training Quarterly (PTQ) 1885 Bob Johnson Drive Colorado Springs, CO 80906 phone: 800-815-6826 email: matthew.sandstead@ nsca.com Reproduction without permission is prohibited. ISSN 2376-0850 PTQ 1.4 | NSCA.COM TABLE OF CONTENTS 04 THE SCOPE OF PRACTICE FOR PERSONAL TRAINERS 10 EXERCISE BEFORE AND AFTER BARIATRIC SURGERY 16 SMALL GROUP TRAINING UTILIZING CIRCUITS 20 HIGH HORMONE CONDITIONS FOR HYPERTROPHY WITH RESISTANCE TRAINING: A BELIEF—NOT EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE IN STRENGTH AND CONDITIONING JUSTIN KOMPF, CSCS, NSCA-CPT, NICK TUMMINELLO, AND SPENCER NADOLSKY, MD CINDY KUGLER, MS, CSCS, CSPS CHAT WILLIAMS, MS, CSCS,*D, CSPS, NSCA-CPT,*D, FNSCA STUART PHILLIPS, PHD, CSCS, FACSM, FACN, ROBERT MORTON, CSCS, AND CHRIS MCGLORY, PHD 24 HOW SAFE ARE SUPPLEMENTS? 26 THE SHARED ADAPTATIONS OF THE TRAINING AND REHABILITATION PROCESSES 30 GETTING THE MOST OUT OF A CERTIFICATION IN PERSONAL TRAINING DEBRA WEIN, MS, RD, LDN, NSCA-CPT,*D, AND JENNA AMOS, RD CHARLIE WEINGROFF, DPT, ATC, CSCS ROBERT LINKUL, MS, CSCS,*D, NSCA-CPT,*D PTQ 1.41.1| |NSCA.COM PTQ NSCA.COM FEATURE ARTICLE THE SCOPE OF PRACTICE FOR PERSONAL TRAINERS JUSTIN KOMPF, CSCS, NSCA-CPT, NICK TUMMINELLO, AND SPENCER NADOLSKY, MD he personal trainer can play a vital role in the overall health and well-being in each of their clients. The purpose of this article is to define the role of the personal trainer. This article will also explore the extent of their scope and will identify when a referral to a healthcare provider would be appropriate. Out of the major, recognized certifying bodies, the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) and the National Strength and Conditioning Association (NSCA) are the only two organizations that have attempted to delineate the specific job description of the personal trainer. T Likewise, according to the NSCA (13): According to the ACSM (1): Personal trainers should fulfill a specific role within the healthcare system and as a healthcare provider. Trainers should have a strong knowledge base in kinesiology, psychology, injury prevention, nutrition, and knowledge of simple medical screening tests. Because of this, they may share certain roles with other healthcare providers such as dietitians, physical therapists, doctors, and psychologists. The ACSM Certified Personal Trainer (CPT) works with apparently healthy individuals and those with health challenges who are able to exercise independently to enhance quality of life, improve health-related physical fitness, performance, manage health risk, and promote lasting health behavior change. The CPT conducts basic pre-participation health screening assessments, submaximal aerobic exercise tests, and muscular strength/endurance, flexibility, and body composition tests. The CPT facilitates motivation and adherence as well as develops and administers programs designed to enhance muscular strength/endurance, flexibility, cardiorespiratory fitness, body composition, and/or any of the motor skill related components of physical fitness (i.e., balance, coordination, power, agility, speed, and reaction time). 4 Personal trainers are health/fitness professionals who, using an individualized approach, assess, motivate, educate, and train clients regarding their health and fitness needs. They design safe and effective exercise programs, provide the guidance to help clients achieve their personal health/fitness goals, and respond appropriately in emergency situations. Recognizing their own area of expertise, personal trainers refer clients to other healthcare professionals when appropriate. Before divulging into the scope of the practice, it is necessary for personal trainers to identify two major components of their profession; research and practical experience, more specifically the application of research to practice. In a review by English et al., the author defines evidence-based training for strength and conditioning professionals as a systematic approach to the training of athletes and clients based on the current best evidence from peer-reviewed and professional reasoning (6). Evidence-based practice is a five step systematic process. The five steps are to develop a question, find evidence, evaluate the evidence, integrate the evidence into practice, and reevaluate the evidence. PTQ 1.4 | NSCA.COM The question should be defined precisely; the authors provide the acronym “PICOT,” which stands for population, intervention, comparison, outcome, and time (6). The question that trainers ask should contain all of these components. For example, is a resistance training program (intervention) of pull-ups or chin-ups (comparison) a better biceps muscle builder (outcome) in healthy college-aged males (population) over the course of 12 weeks (time)? Evidence can be obtained through a variety of sources. Some sources personal trainers should consider using include academic search engines as well as websites like the National Strength and Conditioning Association website (www.nsca.com). Professional experience can also be counted as anecdotal evidence although it is not as strong as a form of evidence as peer-reviewed studies. The ability to evaluate evidence and weigh it against other evidence is an important skill for the success of a personal trainer. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery introduced a system for ranking levels of evidence. The levels of evidence in order from lowest to highest are: expert opinion; case series (no control group); case-control study, retrospective cohort study, and systematic review of level-III studies; prospective cohort study, poor quality randomized controlled trial, systematic review of level II studies, and nonhomogeneous level I studies; and randomized controlled trial and systematic review of level I randomized controlled trials (19). If the evidence presented is strong, then a training modality should be integrated into practice. For example, it has been proven that Olympic-style lifting improves explosive power (3,18). If a personal trainer is working with an athlete that requires explosive power, then they should consider integrating some Olympic-style weightlifting. If the evidence is weak or inconsistent, then perhaps time would be better spent on other training practices (6). Being able to evaluate research means keeping an open mind, as the evidence-based personal trainer will change their practice when new and better evidence demands are presented. Once the personal training field as a whole understands how to evaluate evidence, the scope of practice may expand; however, for now, personal trainers should focus specifically on exercise screening and prescription. Personal trainers can also hold some ground in injury management, psychology, and nutrition. Given the appropriate educational background, personal trainers may also play a role in working with populations with specific medical impairments. EXERCISE ASSESSMENT AND PRESCRIPTION Personal trainers provide resistance training exercise prescription which may improve cardiovascular function, reduce the risk of coronary heart disease and noninsulin dependent diabetes, prevent osteoporosis, reduce the risk of colon cancer, enhance weight loss while preserving muscle mass, improve dynamic stability, and maintain functional capacity and psychological well-being (17). The personal trainer should have an established screening protocol including a physical activity readiness questionnaire as well as a movement screen, which should be conducted before resistance training. The Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire (PAR-Q) is a screening test designed to determine an individual’s risks in participating in physical activity (7). The PAR-Q allows the personal trainer to identify clients with cardiovascular disease or risk factors for disease. If a client is identified as “at risk” they should be referred to a medical professional who will provide a medical evaluation before beginning an exercise program (11). While there are a variety of movement screens available to the personal trainer, they all provide similar outcomes and offer insight as to which exercises can be performed in a safe and non-painful way. Personal trainers should be able to take the information from their screening process to create an exercise program for each client based on their current physical capabilities. Effective strength training programs include multi-joint movements which have been grouped in a variety of different ways. For example, Kritz et al. states that there are seven fundamental patterns: squat, lunge, upper body push, upper body pull, bend, twist, and single-leg patterns (9). If a trainer screens a client and discovers that they are new to exercise and possess limited hip mobility, the personal trainer may want to prescribe a kettlebell hinge exercise rather than a conventional deadlift for the bend category of movement. The inability to apply the screening results to an exercise program could lead to frustration and/or injury. A personal trainer should also be competent in coaching and teaching a variety of exercises. Trainers should be able to coach a basic hinge and bodyweight squat to their clients. In that, the job of the personal trainer is to find the safest and most effective means of helping clients achieve their performance and/or physical goals (e.g., become stronger, bigger, leaner, and faster). The job of the personal trainer is to help their client achieve these goals while working around any aches, pains, or limitations. THE PERSONAL TRAINER’S ROLE WITH INJURED CLIENTS In regards to the specific job description of the physical therapist, according to the Maine Physical Therapy Practice Act (16): The practice of physical therapy includes the evaluation, treatment, and instruction of human beings to detect, assess, prevent, correct, alleviate, and limit physical disability, bodily malfunction, and pain from injury, disease, and any other bodily condition; the administration, interpretation, and evaluation of tests and measurements of bodily functions and structures for the purpose of treatment planning; the planning, administration, evaluation, and modification of treatment and instruction; and the use of physical agents and procedures, activities, and devices for preventive and therapeutic purposes; and the provision of consultative, educational, and other advisory services for the purpose of reducing the incidence and severity of physical disability, bodily malfunction, and pain. PTQ 1.4 | NSCA.COM 5 THE SCOPE OF PRACTICE FOR PERSONAL TRAINERS Additionally, the Florida State Physical Therapy Practice Act describes what a physical therapy assessment entails (14): Physical therapy assessment means observational, verbal, or manual determinations of the function of the musculoskeletal or neuromuscular system relative to physical therapy, including, but not limited to, range of motion of a joint, motor power, postural attitudes, biomechanical function, locomotion, or functional abilities, for the purpose of making recommendations for treatment. Based on these above job descriptions provided by the certifying bodies in each profession, it is clear and obvious that the assessments of muscle imbalances, compensations, movement impairments, and other orthopedic issues and the attempt to correct these issues using specific exercise interventions, is the job of the physical therapist and/or orthopedic specialist, not of the personal trainer. Physical therapists and orthopedic specialists work specifically to fix what is broken or severely injured, whereas personal trainers and coaches work to enhance what is not broken. Put simply, training consists of assessing what they currently have and using general exercise to improve on what they currently have while working around what is broken or severely injured. On the other hand, treatment, which is in the realm of the physical therapist and/or orthopedic specialist, is the diagnosing of what is broken and using specific corrective measures to fix it in order to bring the clients back to what they previously had. When it comes to performing the exercises provided in a way that best fits the client, there are two simple criteria: 1. 2. Comfort: Movement is pain-free, feels natural, and works within the client’s current physiology Control: The client can demonstrate the movement technique and body positioning as provided in each exercise description (e.g., when squatting, the client displays good knee and spinal alignment throughout, along with smooth, deliberate movement) It is important to keep in mind that “comfort” does not mean the sensation associated with muscle fatigue or “feeling the burn.” Discomfort refers to aches and pains that exist outside the gym or flare up when the client performs certain movements. To allow for comfort and control, personal trainers may have to modify (i.e., shorten) the range of motion or adjust the hand or foot placement of a particular exercise to best fit the client’s current ability and anatomy. THE PERSONAL TRAINER’S ROLE IN PSYCHOLOGY AND NUTRITION COUNSELING The personal training profession has a solid base not just in exercise, but in nutrition as well (2). However, a personal trainer is not qualified like a Registered Dietitian (RD), who can write meal plans for clients. Nutrition is related to psychology in that most clients have a fair and very general understanding of what they need to do to improve their eating habits. The real question, and the one personal trainers can help with, is why do they not take the steps to become healthy? Personal trainers should be able 6 to disseminate information on nutrition, serve as counselors to behavior change, and act as a motivator for health change. This can all be done without writing a specific meal plan for a client. Trainers can implement an effective change protocol to be used to hasten behavior change. Chip and Dan Heath, the authors of the book “Switch: How to Change Things When Change is Hard,” identify two factors that can be modified to help people change (8). The authors talk about the environment which includes the person’s network and the path to change, discussing how small changes are more lasting than big changes. For example, one longitudinal study showed that if a close, same-sex friend became obese, that person has a 71% risk of becoming obese as well (4). Changing environmental habits linked to eating can also help a client lose weight. Successful behavioral modification interventions have worked by limiting the place overweight people eat to one location, which may prevent binge eating or random snacking (15). The book also explains how to direct the client analytically and how to get them on board for long-term goals emotionally (8). Some initial questions a personal trainer may ask a client could include (8): 1. How ready are you to change on a scale of 1-10? 2. How important is it for you to change on a scale of 1-10? 3. How confident are you that you can change on a scale of 1-10? 4. Of your five closest friends, spouses, partners, and siblings, how many of them place a strong emphasis on healthy living? 5. Name the people that do and your relationship with them. 6. Are there any people that are close to you that you feel negatively affect your health goals? If so, who are these people and what is your relationship to them? THE PERSONAL TRAINER’S ROLE IN MEDICAL CARE Practicing medicine is not within the scope of practice for the personal trainer. However, there are certain conditions that could be easily screened by a personal trainer especially if a client does not spend much time with their physician or even go to their physician regularly. Personal trainers push a healthy all-around lifestyle, which includes diet, exercise, and even sleep. As the obesity epidemic continues, so do the comorbid conditions that accompany it, including osteoarthritis, diabetes, hypertension, and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) (10). Even through physician visits are typically short, hypertension and diabetes can be easily and regularly screened. Osteoarthritis is a very common complaint that a patient will see a doctor for due to pain. OSA, on the other hand, may be missed in a quick doctor visit. While a personal trainer cannot diagnose OSA, it would benefit the client if the personal trainer could recognize the signs of OSA, so that it might not go unnoticed. Personal trainers could ask questions from validated questionnaires to PTQ 1.4 | NSCA.COM NSCA.com NSCA.com know when to refer to a doctor. One such questionnaire, the STOP questionnaire, is an easy way to assess if a client is at risk of having OSA (5): 1. Snoring: Do you snore loudly? (louder than talking or heard through closed doors) Y/N 2. Tired: Do you often feel tired, fatigued, or sleepy during the day? Y/N 3. Observed: Has anyone observed you stop breathing during your sleep? Y/N 4. Pressure: Do you have or are being treated for high blood pressure? Y/N 5. Body mass index (BMI): Is your BMI greater than 35 kg/ m2? 6. Age: Are you over the age of 50? 7. Neck circumference: Is your neck circumference greater than 40 cm? 8. Gender: Is your gender male? Figure 1 provides some basic examples of scenarios that a personal trainer may encounter to help decipher whether it is within the scope of practice or not. It is important for all personal trainers to be familiar with local bylaws on scope of practice, as they may be different depending on where the personal trainer lives. Personal trainers play a vital role in the general health and well-being of their clients, but it is important for the personal trainer to clearly understand the extent of their influence to avoid legal implications and potential injuries to their clients. High risk for OSA = 3 or more questions answered “yes” Low risk for OSA = less than 3 questions answered “yes” FIGURE 1. BASIC EXAMPLES OF A PERSONAL TRAINER’S SCOPE OF PRACTICE (11,12) INJURED CLIENTS NUTRITION AND PSYCHOLOGY Chronic low back pain and local Facilitation of habit change Within the Scope of Practice Pain comes and goes Minor acute pain When a Referral is Necessary Dissemination of nutrition knowledge Motivational interviewing and abetment of change talk Unmanageable pain with movement Eating disorder Unable to complete activities of daily living Metabolic disease Radiating low back pain Client has been following healthy habit changes but is not losing weight PTQ 1.4 | NSCA.COM MEDICINE Practicing medicine is not within the scope of practice; however, trainers may have knowledge of screens to use to make appropriate referrals PAR-Q indicates potential cardiovascular disease Positive screen for OSA or other conditions 7 THE SCOPE OF PRACTICE FOR PERSONAL TRAINERS REFERENCES 1. American College of Sports Medicine. ACSM Certified Personal Trainer job task analysis. ACSM.org. 2010. Retrieved 2014 from http://certification.acsm.org/files/file/JTA%20CPT%20FINAL%20 2012.pdf. 16. Public Laws: 123rd Legislature First Regular Session. Section N-2 32 MRSA 3111-A: Scope of practice. Retrieved 2014 from http://www.mainelegislature.org/ros/LOM/lom123rd/PUBLIC402_ ptN.asp. 2. Carter, L. The personal trainer: A perspective. Strength and Conditioning Journal 23(1): 14-17, 2001. 17. Ratamess, NA, Alvar, BA, Evetoch, TK, Housch, TJ, Kibler, WB, Kraemer, WJ, and Triplett TN. Progression models in resistance training for healthy adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc 41: 687-708, 2009. 3. Channell, BT, and Barfield, JP. Effect of Olympic and traditional resistance training on vertical jump performance improvement in high school boys. The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 22(5): 1522-1527, 2008. 18. Suchomel, TJ, Wright, GA, Kernozek, TW, and Kline, DE. Kinetic comparison of the power development between power clean variations. The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 28(2): 350-360, 2014. 4. Christakis, NA, and Fowler, JH. The spread of obesity in large social network over 32 years. N Engl J Med 357(4): 370-379, 2007. 19. Wright, JG, Swiontkowski, MF, and Heckman, JD. Introducing levels of evidence to the journal. J Bone Joint Surg Am 85(1): 1-3, 2003. 5. Chung, F, Yegneswaran, B, Liao, P, Chung, SA, Vairavanathan, S, Islam, S, Khajehdehi, A, and Shapiro, CM. STOP questionnaire: A tool to screen patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Anesthesiology 108: 812-821, 2008. 6. English, KL, Amonette, WE, Graham, M, and Spiering, B. What is “evidence-based” strength and conditioning? Strength and Conditioning Journal 34(3): 19-24, 2012. 7. Evetovich, TK, and Hinnerichs, KR. Client consultation and health appraisal. In: Coburn, JW, and Malek, MH (Eds.), NSCA’s Essentials of Personal Training. (2nd ed.) Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics; 147-200, 2012. 8. Heath, C, and Heath, D. Switch: How to Change Things When Change Is Hard. New York, NY: Broadway; 2010. 9. Kritz, M, Cronin, J, and Hume, P. Screening the upper body push and pull patterns using bodyweight exercises. Strength and Conditioning Journal 32(3): 72-82, 2010. 10. Kushner, R. Roadmaps for Clinical Practice: Case Studies in Disease Prevention and Health Promotion-A Primer for Physicians; Communication and Counseling Strategies. Chicago, IL: American Medical Association; 2003. 11. McNeely, E. Prescreening for the personal trainer. Strength and Conditioning Journal 30(5): 68-69, 2008. 12. Mikla, T, and Linkul, R. Drawing the line: The CPT’s scope of practice. National Strength and Conditioning Association National Conference, July 2012. ABOUT THE AUTHOR Justin Kompf is the Head Strength and Conditioning Coach at the State University of New York at Cortland. He is a Certified Strength and Conditioning Specialist® (CSCS®) and a Certified Personal Trainer® (NSCA-CPT®) through the National Strength and Conditioning Association (NSCA). Nick Tumminello is the owner of Performance University, which provides practical fitness education for fitness professionals worldwide, and is the author of the book “Strength Training for Fat Loss.” Tumminello has worked with a variety of clients from National Football League (NFL) athletes to professional bodybuilders and figure models to exercise enthusiasts. He also served as a conditioning coach for the Ground Control Mixed Martial Arts (MMA) Fight Team and is a fitness expert for Reebok. Tumminello has produced 15 DVDs, is a regular contributor to several major fitness magazines and websites, and writes a very popular blog at PerformanceU.net. Spencer Nadolsky is a licensed practicing family medicine resident physician. After a successful athletic career at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Nadolsky enrolled in medical school at the Virginia College of Osteopathic Medicine with aspirations to change the world of medicine by pushing lifestyle changes before drugs (when possible). Proper lifting, eating, laughter, and sleeping are medications he advocates. 13. National Strength and Conditioning Association. NSCA Certified Personal Trainer (NSCA-CPT). NSCA.com. Retrieved 2014 from http://www.nsca.com/Certification/CPT/. 14. Official Internet Site of the Florida Legislature: Online Sunshine. The 2014 Florida statutes. 2014. Retrieved 2014 from http://www.leg.state.fl.us/statutes/index.cfm?App_ mode=Display_Statute&Search_String=&URL=0400-0499/0486/ Sections/0486.021.html. 15. Penick, SB, Lilion, R, Fox, S, and Stunkard, AJ. Behavior modification in treatment of obesity. J Behav Med 33: 49-56, 1971. 8 PTQ 1.4 | NSCA.COM NSCA.com PTQ 1.4 | NSCA.COM 9 FEATURE ARTICLE EXERCISE BEFORE AND AFTER BARIATRIC SURGERY CINDY KUGLER, MS, CSCS, CSPS A s reports from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention indicate, obesity continues to remain high and is associated with high morbidity and mortality rates (3). The increase in obesity results in a higher volume of bariatric surgeries being performed (10). This increases the likelihood that exercise professionals working in various settings will encounter patients who are pre- or post-bariatric surgery. This article will address exercise-related issues and programming needs specific to the bariatric surgical client. The primary exercise objectives pre-surgery are to assess the client’s ability to follow the lifestyle change necessary for longterm success and to decrease the surgical risks by increasing cardiorespiratory fitness (3,16). After surgery, not only is exercise essential for long-term weight loss, it has also been shown to be critical in reducing health risks (5). TYPES OF SURGERY PRE-SURGICAL TESTING Bariatric surgery falls into two main categories, restrictive procedures and malabsorptive procedures. Both of these types can be done either laparoscopically or with an open, larger incision. Restrictive procedures include gastric band and sleeve gastrectomy. These procedures decrease the size of the stomach reservoir so as to limit food intake. Malabsorptive procedures include biliopancreatic diversion, in which a portion of the stomach is removed and a part of the small bowel is bypassed; thus, causing weight loss by decreased absorption of food. The Roux-en-Y gastric bypass procedure is another malabsorptive procedure which also includes a restrictive component. PRE-SURGICAL ASSESSMENT Due to the possible complications and risks of surgery, a multidisciplinary pre-operative assessment is done to determine appropriate surgical candidates (11,13). The patient should have a 10 comprehensive medical, physical, and psychological assessment. See Table 1 for pre-screening criteria examples. Exercise testing is beneficial to assist in exercise prescription (initial and ongoing), monitoring progress and giving feedback to the client, trainer, and physician. Initial testing should be done pre-surgery and repeated at regular intervals—a minimum of every three months post-surgery is recommended. Prior to testing and exercise, medical clearance from the patient’s surgeon or primary physician should be obtained (1). Ideally, yet rarely available, having results of a physician-supervised stress test to assist in program design and risk assessment would be beneficial (7). Additional beneficial tests include (8,17): • Circumference measurements • Body composition (using dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry [DEXA] or body fat assessment) • 6-min walk test • Sit and reach (modified if indicated) PTQ 1.4 | NSCA.COM • Grip dynamometer • Modified push-up (wall if indicated) • Metabolic testing (indirect calorimetry to determine resting metabolic rate) PRE-SURGICAL EXERCISE Physical activity recommendations should take into account musculoskeletal issues, activity tolerance, along with personal preferences. Adherence will decrease if the program is not practical, easily accomplished, and able to be integrated into an individual’s lifestyle. A gradual progression of aerobic exercise based on tolerance, as well as resistance training and flexibility training is recommended. In order to meet the pre-surgical exercise goals of predicting long-term success via lifestyle change and decreasing surgical risks, exercise should begin 8 – 12 weeks prior to surgery. Those with weight bearing limitations should focus on low-impact exercise such as recumbent bicycles, chair exercise, and water exercise. With water exercise, finding an environment the client will feel comfortable in will be important. Utilizing assistive devices such as canes, grocery carts, or walking sticks along with any needed supportive devices such as braces/ sleeves, orthotics, or abdominal binders may assist in successful ambulation. The overall goal is to establish a consistent routine of cardiovascular exercise 3 – 5 times per week at low levels. Often this population begins with very low exercise tolerance. Many will need to start at 5 – 10 min of exercise and progress to 30 min. This may include intermittent bouts working towards the recommended 150 min per week (16). Resistance training should include one set of 12 – 15 repetitions 2 – 3 times per week utilizing bands, tubing, and/or bodyweight with 8 – 10 exercises for a total body workout. Important in exercise selection is to include exercises for the abdominal musculature. This will assist in post-surgical movement and recovery. Exercises may need to be designed to be performed primarily in a sitting position, with limited standing positions as tolerated. See Table 2 for a sample resistance training program. POST-SURGICAL EXERCISE PRESCRIPTION Quality of life can be greatly improved after successful bariatric surgery (5). Exercise is one of the key tools for achieving weight loss and preventing weight gain post-surgery (14). Resistance exercise may also help by preventing muscle loss associated with rapid weight loss, increasing bone strength, and decreasing the chance of osteoporosis (8,9). Immediate post-surgical exercise may also reduce the risk of blood clots and other post-operative complications. In addition, it can help patients tolerate their post-operative diet, assist in alleviating nausea, and aid in getting the digestive system moving again. Post-bariatric surgery exercise is consistent with guidelines prescribed for obese clients (15). CARDIORESPIRATORY EXERCISE Initial in-hospital exercise through two weeks post-surgery should consist of low-level exercise such as walking, seated marching, chair boxing, or stationary recumbent bicycling as tolerated (usually 5 – 10 min sessions) 3 – 4 times per day. Increasing duration slowly to 20 – 30 min, using multiple bouts is acceptable to assist in progress. During the next 2 – 4 weeks post-surgery, additional modalities can be added along with water exercise if the incision has healed fully. Continue progression toward 30 – 40 min sessions for 5 – 6 times per week. After one month, progress toward 40 – 60 min for 5 – 6 times per week. The initial goal should be to obtain 150 total min per week with a longer term goal of 300 total min per week (15). Intermittent, interval, and circuit training exercise protocols can be useful in aiding this progression. A typical progression is presented in Table 3. RESISTANCE EXERCISE Prior to starting post-surgery resistance training, clearance from the surgeon is required to ensure the abdominal muscles have healed fully. Abdominal exercises are important to include, but should wait until either 3 – 6 months post-surgery or upon obtaining surgeon’s clearance. The length of healing time before beginning abdominal exercises is dependent on whether the surgery was done laparoscopically or open. Clearance for general resistance training can typically be obtained in about 4 – 8 weeks post-surgery. Due to a bariatric client’s initial size, they usually do not fit comfortably in selectorized equipment; therefore, the use of bands, tubing, free weights, and bodyweight exercises may be more suitable alternatives (17). Guidelines for resistance training follow those recommended for obese clients (15). A typical resistance training progression is presented in Table 4. Providing variety and time efficient workouts may assist the client’s progress and in keeping the client’s interest levels high. One method through which this can be accomplished is to create a circuit training program incorporating biking for approximately 5 min or treadmill walking with 30 s intervals of resistance training stations. FLEXIBILITY EXERCISE As recommended for joint mobility, stretching is indicated for a well-rounded fitness program. Light stretching can be done after the initial warm-up. To increase flexibility, stretch post-exercise after muscles are warm. Flexibility exercises should be done 2 – 3 times per week, 3 – 4 repetitions per muscle group and static stretches should be held 15 – 60 s (15). POPULATION-SPECIFIC CONSIDERATIONS Several special concerns may affect exercise programming, including exercise selection, intensity, and instruction. Special considerations include psychological/emotional status, comorbidities, size and deconditioning, skin issues, and postsurgical concerns (6,8,15,17). See Table 5 for special consideration and recommendations. Studies have shown that modern society has little respect for morbidly obese individuals (19). Stigmatization may lead to a limited number of friends and social involvement, along with depression (3). Organizations and personal trainers working with the obese should identify if they have any weight bias and include sensitivity training. Sensitivity training should include knowledge on the complex etiology of obesity, compassion and empathy training, and environmental awareness and adaptation needed to create an atmosphere of acceptance (9). It can often be helpful if an organization or personal trainer can refer a client to a qualified individual within their professional network for appropriate assistance. PTQ 1.4 | NSCA.COM 11 EXERCISE BEFORE AND AFTER BARIATRIC SURGERY CONCLUSION Bariatric surgery is not the “easy way out” or a cosmetic procedure. It creates a forced lifestyle change, which can be lifesaving in some cases. Bariatric surgery is one tool to assist in weight loss for those that meet the requirements. For longterm success, healthy eating habits, stress management, social support, regular exercise, and increased daily activity are essential. Personal trainers play a critical role in helping clients to adopt the lifestyle that is needed for both recovery and long-term success by addressing proper exercise protocols and providing appropriate recommendations. As personal trainers, working with bariatric clients can be challenging, yet also very rewarding. REFERENCES 1. Abbott, A. Personal training – litigation insulation. ACSM’s Health and Fitness Journal 15(5): 40-44, 2011. 2. Barbalho-Moulim, C, Miguel, G, Forti, E, Campos, F, and Costa, D. Effects of preoperative inspiratory muscle training in obese women undergoing open bariatric surgery: Respiratory muscle strength, lung volumes, and diaphragmatic excursion. Clinics 66(10): 1721-1727, 2011. 3. Bond, D, Evans, R, DeMaria, E, Wolfe, L, Meador, J, Kellum, J, Maher, J, and Warren, B. Physical activity and quality of life improvements before obesity surgery. Am J Health Behav 30(4): 422-434, 2006. 4. Brzozowska, M, Sainsbury, A, Eisman, J, Baldock, P, and Center, J. Bariatric surgery, bone loss, obesity, and possible mechanisms. Obesity Reviews 14: 52-67, 2013. 5. Chapman, N, Hill, K, Taylor, S, Hassanal, M, Straker, L, and Hamdorf, J. Patterns of physical activity and sedentary behavior after bariatric surgery: An observational study. Surg Obes Relat Dis 10(3): 524-530, 2014. 6. Cheifetz, O, Lucy, S, Overend, T, and Crowe, J. The effect of abdominal support on functional outcomes in patients following major abdominal surgery: A randomized controlled trial. Physiotherapy Canada 62: 242-253, 2010. 7. deJong, A. Cardiopulmonary exercise testing in assessing the risk of bariatric surgery, implications for allied health professionals. ACSM’s Health and Fitness Journal 12(4): 38-40, 2008. 8. Drew, K. Exercise and bariatric surgery. ACSM’s Certified News 22(3): 11-15, 2012. 12. McMahon, M, Sarr, M, Clark, M, Gall, M, Knoetgen III, J, Service, F, Laskowski, E, and Hurley, D. Clinical management after bariatric surgery: Value of a multidisciplinary approach. Mayo Clinic Proceedings 81(10 suppl): s34-s45, 2006. 13. Owens, C, Abbas, Y, Ackroyd, R, Barron, N, and Khan, M. Perioperative optimization of patients undergoing bariatric surgery. Journal of Obesity 81(10 suppl): s25-s33, 2012. 14. Richardson, W, Plaisance, A, Periou, L, Buquoi, J, and Tillery, D. Long-term management of patients after weight loss surgery. The Ochsner Journal 9: 154-159, 2009. 15. Smith, D, and Fiddler, R. In: NSCA’s Essential of Personal Training (2nd ed.) Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics; 489-505, 2012. 16. Sorace, P, and LaFontaine, T. Lifestyle intervention: A priority for long-term success in bariatric patients. ACSM’s Health and Fitness Journal 11(6): 19-25, 2007. 17. Sorace, P, and LaFontaine, T. Personal training post-bariatric surgery patients: Exercise recommendations. Strength and Conditioning Journal 32(3): 101-104, 2010. 18. Tessier, A, Zavorsky, G, Jun Kim, D, Carli, F, Christou, N, and Mayo, N. Understanding the determinants of weight-related quality of life among bariatric surgery candidates. Journal of Obesity Epub Jan 12, 2012. 19. Vartanian, L, and Novak, S. Internalized societal attitudes moderate the impact of weight stigma on avoidance of exercise. Obesity 19(4): 757-762, 2011. 20. Wollner, S, Adair, J, Jones, D, and Blackburn, G. Preoperative progressive resistance training exercise for bariatric surgery patients. Bariatric Times 7(5): 11-13, 2010. ABOUT THE AUTHOR Cindy Kugler is currently employed by the Bryan Health System in Lincoln, NE. She has worked as an exercise specialist for cardiac/ pulmonary rehabilitation, a department manager, and is currently the LifePoint Clinical Liaison. She has assisted with lifestyle modification for those with chronic disease and worksite health promotion for her organization and others. She obtained her Master of Science degree in Exercise Physiology from the University of Nebraska Omaha and is currently the Chair of the National Strength and Conditioning Association (NSCA) Certified Special Populations Specialist® (CSPS®) certification committee. 9. Kushner, R. Roadmaps for Clinical Practice: Case Studies in Disease Prevention and Health Promotion-A Primer for Physicians; Communication and Counseling Strategies. Chicago, IL: American Medical Association; 2003. 10. Manchester, S, and Roye, G. Bariatric surgery, an overview for dietetics professionals. Nutrition Today 46(6): 264-273, 2011. 11. McCullough, P, Gallagher, M, deJong, A, Sandberg, K, Trivax, J, Alexander, D, Kasturi, G, Jafri, S, Krause, K, Chengelis, D, Moy, J, and Franklin, B. Cardiorespiratory fitness and short-term complications after bariatric surgery. Chest 130: 517-525, 2006. 12 PTQ 1.4 | NSCA.COM NSCA.com TABLE 1. SCREENING POTENTIAL SURGICAL CANDIDATES (10) • Adults • Body mass index (BMI) ≥ 40 kg/m2 with no comorbidities • BMI ≥ 35 kg/m2 with obesity-associated comorbidities • Weight loss history • Failure of previous nonsurgical attempts at weight reduction, including nonprofessional programs • Commitment • Expectation that patient will adhere to post-operative care • § Follow-up visits with physician and team members § Recommended medical management, including the use of dietary supplements § Instructions regarding any recommended procedures or tests Exclusions § Reversible endocrine or other disorders that can cause obesity § Current drug or alcohol abuse § Lack of comprehension of risks, benefits, expected outcomes, alternatives, and lifestyle changes required with bariatric surgery § Caution must be used when language or literacy issues are present § Severe food allergies or intolerances must be addressed before surgery TABLE 2. SAMPLE PRE-SURGERY RESISTANCE TRAINING PROGRAM Upper body Lower body Abdominals Wall push-ups Bodyweight Biceps curls Tubing or dumbbell Triceps push-downs/kick backs Tubing or dumbbell Shoulder presses/raises Tubing or dumbbell Seated rows Tubing Chair squats Bodyweight Calf raises Bodyweight Leg presses Tubing Seated crunches Tubing Standing core twists Tubing or dumbbell PTQ 1.4 | NSCA.COM 13 EXERCISE BEFORE AND AFTER BARIATRIC SURGERY TABLE 3. POST-SURGERY CARDIORESPIRATORY EXERCISE PROGRESSION TIME POST-SURGERY FREQUENCY DURATION Weeks 0 – 2 3 – 4 x/day As tolerated; 5 – 10 min per bout Increase daily activities 20 – 30 min; in minimum of 10 min increments, if needed 5 – 6 x/week Weeks 2 – 4 Focus on increasing duration (increase by 2 – 3 min every 2 – 3 days) 40 – 60 min Increase intensity and utilize intervals 5 – 6 x/week Weeks 4+ TABLE 4. POST-SURGERY RESISTANCE TRAINING PROGRESSION TIME POST-CLEARANCE SETS/REPETITIONS FREQUENCY MUSCLE GROUPS Weeks 1 – 4 (4 – 8 weeks post-surgery) 1 set/12 – 15 reps 2x/week* 8 – 10 exercises; all major muscle groups No abdominal exercises Weeks 4 – 8 2 sets**/12 – 15 reps 2 – 3x/week* 8 – 10 exercises; all major muscle groups Abdominal exercises, if clearance is given 8 – 10 exercises minimum; all major muscle groups Weeks 8+ 3 sets**/8 – 12 reps 2 – 3x/week* Add more functional, postural, balance, and abdominal exercises * Allow 48 hours between sessions ** Approximately 1-min rest intervals 14 PTQ 1.4 | NSCA.COM NSCA.com TABLE 5. SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS (3,6,8,9,12,16,19) CATEGORY Psychological/ Emotional Status Common Comorbidities CONCERNS RECOMMENDATIONS Stigma Sensitivity training Decreased self-esteem Establish excellent rapport Depression Refer to physician or counselor Embarrassment Empathy and listening skills Give home exercise and equipment options Obstructive sleep apnea/fatigue Refer to physician Timing of exercise session with rest Orthopedic/pain (e.g., knees, back, hips, and feet) Choice of appropriate exercise modality (e.g., water, non-weight bearing, etc.) Use of supportive devices (e.g., orthotics, braces/sleeves, etc.) Use of thick large mats Refer to physician for pain control and treatment Instruction in use of rest, ice, and compression Diabetes mellitus Utilize appropriate guidelines for checking blood glucose and exercise Shortness of breath Utilize intermittent exercise and/or interval protocols; utilize dyspnea scale with exercise Panniculus interference Abdominal binder and supportive clothing Exercise fatigue Utilize ratings of perceived exertion scale with exercise, intermittent, and/or interval protocols Chairs available for rest Self-consciousness Awareness of environmental needs such as use of chairs without arms, ability to get up and down off the floor, alternatives to machines they do not fit into, and an exercise area that is more private Give home exercise and equipment options Overheating Cooler environment, fans, wicking clothing, and cooling towel Chafing, yeast, and fungus Use of commercial products according to individual preference Excess skin Use of tighter, supportive, wicking clothing Changing body size/mass Awareness of changing balance and having support when including balance exercises Low energy due to low calorie diet Timing of exercise with meal or snack Utilizing lower intensities and/or intervals Refer to dietitian for nutrient and caloric recommendations Dehydration Consume a minimum of 64 oz of water per day in 1 oz increments Continuous sipping before, during, and after exercise Take water breaks Refer to dietitian as needed Changing relationships with food, family, and friends May sabotage their new lifestyle Need support, encouragement, and empathy Refer to physician and/or counselor as needed Bone loss and osteoporosis Include resistance training and weight bearing exercises Encourage compliance with prescribed supplements Refer to physician and/or dietitian as needed Size/Deconditioning Skin Issues Post-Surgical Concerns PTQ 1.4 | NSCA.COM 15 SMALL GROUP TRAINING UTILIZING CIRCUITS CHAT WILLIAMS, MS, CSCS,*D, CSPS, NSCA-CPT,*D, FNSCA I am often asked the following questions by students and other individuals who are starting a profession in personal training: “What could be changed?” “What could be done differently?” “What population should I work with?” “Is there a specific area of focus to study?” My answer always discusses the benefits of incorporating small group training into their training protocols. I have witnessed many fads and fitness trends over the last 18 years and the one concept that seems to be growing steadily is personal training in a small group setting. How is small group training defined? Here are some differences associated with other types of training in the strength and conditioning industry. Personal Training: In the traditional sense, personal training is performed in a one-on-one setting and typically ranges from 30 – 60 min. Semiprivate: Personal trainer will work with 2 – 3 individuals during the same session for 30 – 60 min. Small Group: Personal trainer will develop a training program for 4 – 10 individuals at the same time. All of these training methods have benefits associated with them; it will depend on the individual’s personal goals, schedule availability, fitness level, and comfort level training with other people. Here are some potential benefits to consider with small group training. FINANCIAL INVESTMENT One of the first questions during the initial inquiries about personal training is “How much does it cost per session?” Many times, individuals may not be able to hire a personal trainer due to a limited budget. For example, a one-on-one session may cost 50 dollars an hour, but in a small group setting a lower rate of 15 dollars per hour may be more realistic. Plus, the total revenue per hour increases for the personal trainer. Using the same example with a small group of eight people, the personal trainer will generate about 120 dollars an hour as opposed to 50 dollars an hour. The small group concept can be a “win-win” for both parties as it generates more revenue and time efficiency for the personal trainer and breaks down the cost barrier for the client. 16 SUPPORT AND MOTIVATION Being part of a group instantly develops a support network for the individuals. This could be family, friends, or coworkers. Working out with like-minded individuals creates the competiveness that may push them to a higher level, while recognizing their own individual fitness strengths. Motivating, encouraging, and driving one another during workouts develops a positive environment and camaraderie amongst the group. Plus, there is accountability that each person must have in a group setting. The people in the group are typically supportive in a positive manner and have a tendency to “call out” those who are missing sessions. People in the group count on individuals to show up, especially when partner-based training and circuit-type training are a part of the overall program design. ADHERENCE, FUN, AND GROUP STRUCTURE Teamwork, group motivation, and encouragement must also be supported by the personal trainer to create fun and challenging workouts. Exercise adherence can be difficult for any individual participating in a fitness program, but it is especially crucial for a beginner. A more dynamic program may lead to higher adherence rates for the individual and the group. Groups can be categorized by assigned, mixed, and team (e.g., coworkers) depending on fitness levels and schedule availability. Beginners and individuals that need programs with a little less intensity can be assigned to the same group. Individuals with prior fitness experience can be assigned to a mixed group where the personal trainer can modify the training within the sessions to meet some of their specific goals. Team groups can develop their own goals as a group and individually. For example, they may want to lose a specific amount of weight as an organization. All three of these groups can set goals as a group and as individuals every 8 – 12 weeks to maintain success and motivation. DEFINITIONS, RESEARCH, AND PROGRAM DESIGN Circuits, supersets, compound sets, and complex sets are great ways to keep workouts fast-paced, fun, challenging, and energetic. Circuits typically utilize 10 – 15 exercises and can either be grouped together as one big circuit or grouped together focusing on upper body, lower body, or core. To incorporate greater challenges with a circuit, programming may include supersets, compound sets, PTQ 1.4 | NSCA.COM and complex sets. A superset consists of two exercises involving opposing muscle or action of the muscles (e.g., pairing bench press with lat pull-down). A compound set involves two exercises utilizing the same muscle group or action of the muscle (e.g., pairing single-arm dumbbell row and bodyweight inverted row). A complex set combines a power movement with a strength movement (e.g., pairing countermovement vertical jump and squat) and usually flow from one movement to the next in terms of the finishing position (3). The frequency, intensity, rest intervals, volume, and exercise selection will depend on the overall objective of the group (2). Circuit training has been shown to improve multiple fitness components including time to lactate threshold and increased endurance (2). Increased maximal oxygen consumption (VO2max), functional capacity, improved pulmonary ventilation, reduced body fat, and overall improved body composition are some of the improvements that may be elicited when incorporating circuit training where lighter loads are lifted with minimal rest (1). In one study where heavier loads of six repetition maximum (6RM) were used comparing traditional strength training to heavy resistance circuits in resistance trained males showed similar strength and muscle mass improvements to traditional strength training (1). Other findings included similar improvements in power, reductions in body fat, and an increased performance on the 20-meter shuttle run (1). REFERENCES 1. Alcaraz, P, Perez-Gomez, J, Chavarrias, M, Blazavich, A. Similarity in adaptations to high-resistance training vs. traditional strength training in resistance trained men. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 25(9): 2519-2527, 2011. 2. Waller, M, Miller, J, and Hannon, J. Resistance circuit training: It’s application for the adult population. Strength and Conditioning Journal 33(1): 16-22, 2011. 3. Williams, C. Complex set variations: Improving strength and power. Personal Training Quarterly 1(3): 20-25, 2014. ABOUT THE AUTHOR Chat Williams is the Supervisor for Norman Regional Health Club. He is a past member of the National Strength and Conditioning Association (NSCA) Board of Directors, NSCA State Director Committee Chair, Midwest Regional Coordinator, and State Director of Oklahoma (2004 State Director of the Year). He also served on the NSCA Personal Trainers Special Interest Group (SIG) Executive Council. He is the author of multiple training DVDs. He also runs his own company, Oklahoma Strength and Conditioning Productions, which offers personal training services, sports performance for youth, metabolic testing, and educational conferences and seminars for strength and conditioning professionals. PROGRAM EXAMPLES Here are a couple of examples including different types of circuits that can be incorporated into the training program design. Each workout should begin with a warm-up and end with a cool-down and/or stretching. 10 STATION CIRCUIT (TABLE 1) This circuit includes 10 different exercises targeting the full body. This may be useful for a beginner training program that has 10 participants. Each individual can rotate through three times completing 10 – 15 repetitions for each exercise. Rest between each exercise should be approximately 30 s or just enough time to move to the next exercise. 3 MINI-CIRCUITS (TABLE 2) This circuit includes three mini-circuits which all contain four exercises. These mini-circuits will include supersets, compound sets, and complex sets. This full body workout is not recommended for beginners as it contains intermediate level exercises. PTQ 1.4 | NSCA.COM 17 SMALL GROUP TRAINING UTILIZING CIRCUITS TABLE 1. 10 STATION CIRCUIT SAMPLE MOVEMENT AREA TARGETED SET/REPETITIONS Bench presses Upper body 3/10 Leg presses Lower body 3/10 Single-arm dumbbell rows Upper body 3/10 Seated leg curls Lower body 3/10 Stability ball abs (modify for group ability) Core 3/15 Seated overhead presses Upper body 3/10 Cable cross posterior deltoids (modify for group ability) Upper body 3/10 Calf raises Upper body 3/10 Dumbbell curls Upper body 3/10 Triceps extensions Upper body 3/10 EXERCISE TYPE SETS/REPETITIONS Box jumps Complex set 3/5 Leg presses Complex set 3/10 Leg extensions Superset 3/10 Leg curls Superset 3/10 EXERCISE TYPE SETS/REPETITIONS Seated chest presses Compound set 3/10 Push-ups Compound set 3/10 TABLE 2. 3 MINI-CIRCUITS SAMPLE Circuit 1 Circuit 2 Lat pull-downs Compound set 3/10 Pull-ups Compound set 3/10 EXERCISE TYPE SETS/REPETITIONS Hanging leg raises Compound set 3/12 Circuit 3 18 Crunches Compound set 3/15 Straight-bar curls Superset 3/10 Overhead triceps extensions Superset 3/10 PTQ 1.4 | NSCA.COM NSCA.com Professional Conditioning Solutions to Achieve Peak Performance UltraFit™ SlamBall™ Professional Conditioning Solutions to Achieve Peak Performance • A true Unconditional 100% Satisfaction Guarantee • The best customer service • The fastest shipping Call today for your FREE catalog! Phone: 1-800-847-5334 • Fax: 1-800-862-0761 Online: www.GopherPerformance.com PTQ 1.4 | NSCA.COM 19 FEATURE ARTICLE HIGH HORMONE CONDITIONS FOR HYPERTROPHY WITH RESISTANCE TRAINING: A BELIEF—NOT EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE IN STRENGTH AND CONDITIONING STUART PHILLIPS, PHD, CSCS, FACSM, FACN, ROBERT MORTON, CSCS, AND CHRIS MCGLORY, PHD he ability to maintain or increase skeletal muscle mass (hypertrophy) has clear advantages in the athletic setting. An increase in the cross-sectional area (CSA) of skeletal muscle fibers ultimately occurs when the net rate of muscle protein synthesis (MPS) exceeds that of muscle protein breakdown (MPB) (16). Both resistance exercise and protein ingestion stimulate a significant increase in the rates of MPS over and above rates of MPB and, when combined, are synergistic in their effects. Hence, frequent resistance exercise and protein consumption support increases in MPS and may induce skeletal muscle remodelling and hypertrophy (2). T augments muscle hypertrophy and strength, there is not convincing data for GH or for IGF-1 (1,3,10,18). The link between the transient increase in concentration of these hormones and hypertrophy has been explicitly examined in primary research papers (1,13,21,24,25,26,27,28,29). However, the aim of this article is to address the following questions: 1) is the transient postexercise hormonal response playing a role in skeletal muscle hypertrophy? If so, then 2) should hormonal changes influence RT program design and periodization aimed at maximizing muscle hypertrophy? If the answer to the first question is no, then the second question is moot. Despite the wealth of information pertaining to the impact of resistance exercise and protein consumption on MPS, the exact cellular and molecular mechanisms that underpin resistance exercise-induced changes in MPS remain unclear. Many hypotheses have been proposed but some are with little supporting evidence and empirical data. One such hypothesis is that higher elevated concentrations of exercise-induced systemic “anabolic” hormones are needed for attaining optimal hypertrophy with resistance training (RT); a thesis termed the “hormone hypothesis.” The hormone hypothesis seems compelling based on the well-documented knowledge that resistance exercise is followed by a transient (approximately 30 min) systemic elevation of hormones, some of which are “anabolic” (12,26). Notably there are increases in free and protein-bound forms of testosterone (T), growth hormone (GH), and insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1). While there is indisputable evidence to show that exogenous supraphysiological doses of testosterone It has been known for some time that GH secretion increases bone and muscle mass in growing animals and children (8,14,15). It is undeniable that exogenous supraphysiological GH stimulates collagen protein synthesis, but the notion that supraphysiological GH administration directly increases skeletal muscle mass is without direct support (3,24). A plausible argument is that the exogenous GH-mediated increase in connective tissue would allow for more loading, but such a thesis awaits experimental confirmation. Alternatively, increases in GH may exert an indirect anabolic influence via IGF-1, which is synthesized by the liver. 20 Often recognized for its relation with GH, IGF-1 is also transiently elevated post-exercise (28,29). The GH/IGF-1 axis is involved with muscle growth during adolescence where, like T and GH, levels of IGF-1 reach their peak (6). The assertion that IGF-1 is anabolic comes from selective rodent data in which the IGF-1 receptor in skeletal muscle was knocked out and the rates of MPS, in response to 50 “repetitions” in rats (standing on their hind legs), PTQ 1.4 | NSCA.COM was reduced (4). In contrast, removal of the IGF-1 receptor from skeletal muscle in mice did nothing to attenuate load-induced skeletal muscle hypertrophy (21). However, it is important to acknowledge that rodents exhibit marked differences in rates of protein turnover as compared to humans. Moreover, insulin is known to stimulate the phosphorylation (and presumably activation) of the IGF-1 receptor, resistance exercise does not (9). Given that insulin plays only a permissive role in the regulation of human MPS, these data suggest that IGF-1 exerts a minimal, if any, impact on resistance exercise-induced increases in MPS (7). In fact, one year of IGF-1 administration was shown to have no noticeable impact on bone or body composition in older women (10). An often-used, but categorically incorrect, argument in support of the hormone hypothesis is the marked potency of T when given as an exogenous anabolic agent (1). There are, however, critically important differences between pharmacological doses (or pharmacological suppression) of T and the comparatively minor and fleeting increases in post-exercise T. For example, when young men are administered 600 mg weekly for 10 weeks, bringing total T concentrations from approximately 500 ng/dl (nanograms per deciliter) to 3,000 ng/dl, there is an increase in both muscle mass and strength (1). We also know that when T is pharmacologically supressed to one tenth of normal levels, the training response is attenuated (13). Studies administering T to hypogonadal elderly men (60 or more years old) found increased muscle protein anabolism (5). The exercise-induced increases in T concentration, which are no greater than the daily diurnal fluctuation of the hormone, are simply not comparable in magnitude (usually 1/10th to 1/100th of the pharmacologic dose) or duration (approximately 30 min versus constant elevation dependent on dosing in pharmacologic models) to what is seen with exogenous supplementation (20). An interesting finding for the hormonal hypothesis is that, despite the lower acute increases in T post-resistance exercise, females demonstrate the same relative hypertrophic response to resistance exercise (11). A common misconception is that the relative hypertrophic response to RT is lower in women compared to men. For example, despite a 45-fold lower exercise-induced T response in women, (compared to men), women achieve similar relative MPS post-exercise (26). Hubal et al. also found that women, who had roughly about one tenth of the resting T levels as men, had the same relative hypertrophic response (11). If the post-exercise T response were a determinant of MPS and subsequent hypertrophy, then women would have a lower relative hypertrophic and MPS response, but that is not the case. This important consideration is frequently overlooked when evaluating the hormone hypothesis. In another study, hypertrophy and strength gains of limbs were examined within the same individual under two different hormonal environments (28). Twelve young men trained each of their elbow flexors every 72 hr with one arm being grouped into a low hormonal (LH) environment and the other into a high hormonal (HH) environment for the duration of the study. Despite 15 weeks of RT with limbs in a LH or HH environment, there were no differences between groups in muscle CSA or strength following training (28). It was concluded that muscle hypertrophy and strength with RT in young men was unaffected by exposure to exercise-induced elevations in GH, IGF-1, or T (Figure 1) (28). In general, these studies provide evidence that exercise-induced hypertrophic adaptation in skeletal muscle occurs independently of exercise-induced endogenous anabolic hormone concentrations (25,28). Nonetheless, the lack of bona fide RT trial data to support the hormone hypothesis has not prevented the propagation of dogmatic beliefs that are not evidence-based recommendations for “effective” RT leading to hypertrophy. In summary, it appears as if there is little evidence to support the assertion that transient post-exercise increases in hormones are causative in normal RT-stimulated hypertrophy. If how one responds to RT is not hormonally driven, then what drives it? One theory is that hypertrophy is facilitated via local musclemediated mechanisms that are intrinsic to the skeletal muscle (24). Instead, the post-exercise increase in hormones is a generic stress response seen after many forms of high-intensity exercise, many of which do not lead to hypertrophy (i.e., middle distance running) (23). Thus, in failing to establish a direct causal, or even associative, link between post-exercise hormonal concentrations directly calls into question their measurement as a driver of any kind of decision making or planning of RT programs or periodization of training. It is recommended that the attainment of RT-induced hypertrophy based on measurement of systemic hormone concentrations is a belief, and not an evidence-based practice. In contrast to the belief that the post-exercise hormonal response is an important mediator of hypertrophy, published studies have yielded little mechanistic support or valid clinical data to uphold this proposition. In fact, in most studies that have investigated whether the repeated increase in systemic “anabolic” hormones promote hypertrophy, it seems as though none have provided any unequivocal support for this assertion. In a large cohort (n = 56) of young men, associations were examined between acute increases in T, GH, and IGF-1 with lean body mass, fiber CSA, and leg press strength following a 12-week RT protocol (25). The exerciseinduced hormonal response was not correlated with gains in lean body mass, fiber CSA, or strength (25). PTQ 1.4 | NSCA.COM 21 HIGH HORMONE CONDITIONS FOR HYPERTROPHY WITH RESISTANCE TRAINING: A BELIEF—NOT EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE IN STRENGTH AND CONDITIONING REFERENCES 1. Bhasin, S, Storer, T, Berman, N, Callegari, C, Clevenger, B, Phillips, J, Bunnell, T, Tricker, R, Shirazi, A, and Casaburi, R. The effects of supraphysiologic doses of testosterone on muscle size and strength in normal men. The New England Journal of Medicine 335(1): 1-7, 1996. 2. Burd, N, Tang, J, Moore, D, and Phillips, S. Exercise training and protein metabolism: Influences of contraction, protein intake, and sex-based differences. Journal of Applied Physiology 106: 1609-1701, 2009. 3. Doessing, S, Heinemeier, K, Holm, L, Mackey, A, Schjerling, P, Rennie, M, Smith, K, Reitelseder, S, Kapplegaard, A, Rasmussen, M, Flyvbjerg, A, and Kjaer, M. Growth hormone stimulates the collagen synthesis in human tendon and skeletal muscle without affecting myofibrillar protein synthesis. Journal of Physiology 588(2): 341–351, 2010. 4. Fedele, M, Lang, C, and Farrell, P. Immunization against IGF-1 prevents increases in protein synthesis in diabetic rats after resistance exercise. American Journal of Physiology, Endocrinology and Metabolism 280: E877-E885, 2001. 5. Ferrando, A, Sheffield-Moore, M, Yeckel, C, Gilkison, C, Jiang, J, Achasoa, A, Lieberman, S, Tipton, K, Wolfe, R, and Urban, R. Testosterone administration to older men improves muscle function: Molecular and physiological mechanisms. American Journal of Physiology 282(3): E601-607, 2002. 6. Goldspink, G, Wessner, B, Tschan, H, and Bachl, N. Growth factors, muscle function and doping. Endocrine and Metabolism Clinics 39(1): 169-181, 2010. 7. Greenhaff, P, Karagounis, L, Peirce, N, Simpson, E, Hazell, M, Layfield, R, Wackerhage, H, Smith, K, Atherton, P, Selby, A, and Rennie, M. Disassociation between the effects of amino acids and insulin on signaling, ubiquitin ligases, and protein turnover in human muscle. American Journal of Physiology - Endocrinology and Metabolism 295(3): E595-604, 2008. 12. Kraemer, W, and Ratamess, N. Hormonal responses and adaptations to resistance exercise and training. Sports Medicine 35: 339-361, 2005. 13. Kvorning, T, Anderson, M, Brixen, K, and Madsen, K. Suppression of endogenous testosterone production attenuates the response to strength training: A randomized, placebocontrolled, and blinded intervention study. American Journal of Physiology, Endocrinology and Metabolism 291(6): 1325-1332, 2006. 14. Lissett, C, and Shalet, S. Effects of growth hormone on bone and muscle. Growth Hormone and IGF Research 10: S95-101, 2000. 15. Pell, J, and Bates P. The nutritional regulation of growth hormone action. Nutrition Research Reviews 3: 163-92, 1990. 16. Phillips, S. Protein requirements and supplementation in strength sports. Nutrition 20(7-8): 689-695, 2004. 17. Pritzlaff, C, Wideman, L, Weltman, J, Abbott, R, Gutgesell, M, Hartman, M, Veldhuis, J, and Weltman, A. Impact of acute exercise intensity on pulsatile growth hormone release in men. Journal of Applied Physiology 87: 498-504, 1999. 18. Rennie, M. Claims for the anabolic effects of growth hormone: A case of the Emperor’s new clothes? British Journal of Sports Medicine 37: 100-105, 2003. 19. Rosen, C. Growth hormone and again. Endocrine 12: 197-201, 2000. 20. Schroeder, E, Villanueva, M, West, D, and Phillips, S. Are acute post-resistance exercise increases in testosterone, growth hormone, and IGF-1 necessary to stimulate skeletal muscle anabolism and hypertrophy? Medicine and Science in Sport and Exercise 45(11): 2044-2051, 2013. 21. Spangenburg, E, Le Roith, D, Ward C, and Bodine, S. A functional insulin-like growth factor receptor is not necessary for load-induced skeletal muscle hypertrophy. The Journal of Physiology 586: 283-291, 2008. 8. Gregory, J, Greene, S, Jung, R, Scrimgeour, C, and Rennie, M. Changes in body composition and energy expenditure after six weeks’ growth hormone treatment. Archives of Disease in Childhood 66: 598–602, 1991. 22. Staron, R, Karapond, D, Kraemer, W, Fry, A, Gordon, S, Falkel, J, Hagerman, F, and Hikida, R. Skeletal muscle adaptations during early phase of heavy-resistance training in men and women. Journal of Applied Physiology 76(3): 1247-1255, 1994. 9. Hamilton, D, Philip, A, MacKenzie, M, and Baar, K. A limited role for PI(3,4,5)P3 regulation in controlling skeletal muscle mass in response to resistance exercise. PLOS One 5(7): e11624, 2010. 23. Vuorimaa, T, Ahotupa, M, Hakkinen, K, and Vasankari, T. Different hormonal response to continuous and intermittent exercise in middle-distance and marathon runners. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine and Science in Sports 18(5): 565-572, 2008. 10. Hoffman, A, Marcus, R, Lee, S, Matthias, D, Yesavage, J, Friedman, L, Holloway, L, Pollack, M, Grillo, J, Moynihan, S, Butterfield, G, and Friedlander, A. One year of insulin-like growth factor 1 treatment does not affect bone density, body composition, or psychological measures in postmenopausal women. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 86(4): 1496-1503, 2001. 11. Hubal, M, Gordish-Dressman, H, Thompson, P, Price, T, Hoffman, E, Angelopoulos, T, Gordon, P, Moynga, N, Pescatello, L, Visich, P, Zoeller, R, Seip, R, and Clarkson, P. Variability in muscle size and strength gain after unilateral resistance training. Medicine and Science in Sport and Exercise 37(6): 964-972, 2005. 22 24. West, D, and Phillips, S. Anabolic processes in human skeletal muscle: Restoring the identities of growth hormone and testosterone. The Physician and Sportsmedicine 38(3): 97-104, 2010. 25. West, D, and Phillips, S. Associations of exercise-induced hormone profiles and gains in strength and hypertrophy in a large cohort after weight training. European Journal of Applied Physiology 112: 2693-2702, 2012. PTQ 1.4 | NSCA.COM NSCA.com 26. West, D, Burd, N, Churchward-Venne, T, Camera, D, Mitchell, C, Baker, S, Hawley, J, Coffey, V, and Phillips, S. Sex-based comparisons of myofibrillar protein synthesis after resistance exercise in the fed state. Journal of Applied Physiology 112(11): 1805-1813, 2012. 27. West, D, Burd, N, Staples, A, and Phillips, S. Human exercisemediated skeletal muscle hypertrophy is an intrinsic process. The International Journal of Biochemistry and Cell Biology 42: 13711375, 2010. 28. West, D, Burd, N, Tang, J, Moore, D, Staples, A, Holwerda, A, Baker, S, and Phillips, S. Elevations in ostensibly anabolic hormones with resistance exercise enhance neither traininginduced muscle hypertrophy nor strength of the elbow flexors. Journal of Applied Physiology 108(1): 60-67, 2010. 29. West, D, Kujbida, G, Moore, D, Atherton, P, Burd, N, Padzik, J, De Lisio, M, Tang, J, Parise, G, Rennie, M, Baker, S, and Phillips, S. Resistance exercise-induced increases in putative anabolic hormones do not enhance muscle protein synthesis or intracellular signalling in young men. The Journal of Physiology 587: 5239-5247, 2009. ABOUT THE AUTHOR Stuart Phillips is a Fellow of the American College of Sports Medicine (FACSM) and the American College of Nutrition (FACN). He is a professor at McMaster University in the Kinesiology Department and is also an Associate Member of the School of Medicine at McMaster. Phillips’ research is focused on the interaction between skeletal muscle contraction and nutritional support in the regulation of muscle mass. He has more than 200 published papers and has delivered more than 120 public presentations. Robert Morton is a graduate student working with Dr. Stuart Phillips at McMaster University. He is a personal trainer, rugby player, and strength and conditioning coach possessing a strong passion for the application of science in sport. Having interned with Hockey Canada, the University of Louisville, the Ontario Soccer Association, the Hamilton Bulldogs of the American Hockey League (AHL), and McMaster University Athletics, Morton hopes to work within highlevel sport organizations. His goal is to be an industry-leader in sport science and to bridge the gap between science and sport. Chris McGlory is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow and a graduate of Liverpool John Moores University (where he attained his Master of Science degree) and the University of Stirling (where he completed his PhD). He competed in high-level rugby until injury forced a premature exit from the game. McGlory is very interested in the link between muscle contraction and mechanisms leading to hypertrophy in human skeletal muscle. FIGURE 1. HIGH AND LOW HORMONE CONDITIONS ON HYPERTROPHY, AGGREGATE EXPOSURE, AND STRENGTH Panel A: Hypertrophy of the biceps brachii after a 15-week RT program under high hormone (HH) or low hormone (LH) conditions. Panel B: Aggregate exposure (mean area under the curve [AUC] post-exercise before and after training) for free testosterone (fT). Panel C: Mean increase in maximal elbow flexor strength – one repetition maximum (1RM); values are means ± standard error of the mean. Figures redrawn with data from West et al. with permission (28). PTQ 1.4 | NSCA.COM 23 HOW SAFE ARE SUPPLEMENTS? DEBRA WEIN, MS, RD, LDN, NSCA-CPT,*D, AND JENNA AMOS, RD S upplement use in the United States has been steadily increasing over the last several decades. Consumers spent almost 34 billion dollars on herbal and dietary supplements in 2007 alone, which was an increase of almost seven billion dollars, or 25%, since 1997 (4). As of 2010, approximately half of all adults in the United States reported taking an herbal dietary supplement (HDS) (4). These adults generally care about their health; they cite health maintenance and improvement as two of the main reasons for beginning a regimen of HDS (1). Interestingly, of the almost 50% of adult consumers who report taking HDS, less than half of those do so because of a healthcare provider’s recommendation (1). This may be related to consumers commonly perceiving supplements as generally safe (4). While consumers may perceive supplements as safe, the regulatory standards set forth by the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994 require less evidence of safety than medications require (3). The act allows the sale of HDS without prior approval of their efficacy or safety by the Federal Drug Administration (FDA) or other regulatory bodies (5). Consumers’ increasing use of supplements coupled with the industry’s lax standards has triggered research to investigate possible negative side effects of supplement use. Previous research by Navarro et al. attempted to quantify negative outcomes, specifically hepatotoxicity (chemical induced liver damage) and associated liver transplant or death, related to HDS and medication use (4). The study recruited individuals from eight United States Drug Induced Liver Injury Network referral centers between 2004 and 2013. The researchers grouped the 839 patients who met inclusion criteria into three categories: liver injury caused by bodybuilding supplements, non-bodybuilding supplements, and medications. The study showed that 130 patients (15.5%) had liver injury related to HDS. The study’s results mirrored the national trend of increasing supplement use as liver injury from HDS increased from 7% at the beginning of the study to 20% at the end of the study. In addition, participants with liver injury from HDS took a total of 217 different products. It is worth noting that 42 of these products had unidentifiable ingredients and 21 products contained more than 20 ingredients. 24 In the same study, patients with liver injury resulting from bodybuilding and non-bodybuilding HDS were younger than those with liver injury resulting from medications (5). Patients with liver injury from HDS had a significantly higher proportion of severe cases, including those that required liver transplant or resulted in death (4). This is interesting considering that comorbidities such as diabetes and heart disease were more common among the medication associated liver injury group. A total of 13 patients in the non-bodybuilding HDS-related liver injury group died or received a liver transplant while no patients in the bodybuilding HDS-related liver injury group died or required a transplant. However, patients with liver injury related to bodybuilding HDS experienced increased latency (time between the start of the supplement and the onset of injury) and prolonged jaundice compared to the other two groups (4). Previous case studies and research findings support the possible association between hepatotoxicity and supplement intake. Timcheh-Hariri et al. investigated case studies of individuals who had taken three specific supplements (6). The study concluded possible causality between the supplement use and the hepatotoxicity in the otherwise healthy individuals. Interestingly, liver injury resolved in all cases within one month of stopping supplement intake. Another study by Martin et al. found that 48 military personnel who required evacuation from a military facility had druginduced liver injury. Of those 48, 12 military personnel (25%) were associated with a pre-workout supplement (2). Consumers and healthcare providers should remain aware that the supplement industry has fairly loose regulation, rendering supplement use risky at times. Studies have shown the harm and dangers that certain supplements can cause to otherwise healthy individuals. This suggests a need for more research on the topic to understand the potential problems better. Ultimately, a consumer should always discuss the use of HDS with a physician, pharmacist, or Registered Dietitian (RD) for important information on dosing and possible drug interactions prior to implementation. PTQ 1.4 | NSCA.COM REFERENCES 1. Bailey RL, Gahche JJ, Miller PE, Thomas PR, and Dwyer JT. Why U.S. adults use dietary supplements. JAMA Intern Med 173(5): 355-61, 2013. 2. Martin, DJ, Partridge, BJ, and Shields, W. Hepatotoxicity associated with the dietary supplement N.O.-XPLODE. Ann Intern Med 159(7): 503-504, 2013. 3. National Institutes of Health Office of Dietary Supplements. Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994. Public Law 103-417: 103rd Congress. 1994. Retrieved 2014 from http://ods. od.nih.gov/About/DSHEA_Wording.aspx. 4. Navarro, VJ, Barnhart, H, Bonkovsky, HL, Davern, T, Fontana, RJ, Grant, L, et al. Liver injury from herbals dietary supplements in the U.S. Drug-Induced Liver Injury Network. Hepatology 60(4): 1399-1408, 2014. 5. Stickel F, Kessebohm K, Weimann R, and Seitz HK. Review of liver injury associated with dietary supplements. Liver Int 31(5): 595-605, 2011. ABOUT THE AUTHOR Debra Wein is a recognized expert on health and wellness and designed award-winning programs for both individuals and corporations around the United States. She is the President and Founder of Wellness Workdays, Inc., (www.wellnessworkdays.com) a leading provider of worksite wellness programs. In addition, she is the President and Founder of the partner company, Sensible Nutrition, Inc. (www.sensiblenutrition.com), a consulting firm of registered dietitians and personal trainers, established in 1994, that provides nutrition and wellness services to individuals. She has nearly 20 years of experience working in the health and wellness industry. Her sport nutrition handouts and free weekly email newsletters are available online at www.sensiblenutrition.com. Jenna Amos is a Registered Dietitian (RD). She is a graduate of Boston University’s undergraduate dietetics program and of Virginia Commonwealth University Health System’s dietetic internship. 6. Timcheh-Hariri A, Balali-Mood M, Aryan E, Sadeghi M, and Riahi-Zanjani B. Toxic hepatitis in a group of 20 male bodybuilders taking dietary supplements. Food Chem Toxicol 50(10): 3826-3832, 2012. New Product Clinically proven to help enhance endurance and recovery by repairing and healing muscle tissue at the molecular level 20% Faster Recovery Time 16% Increase in Endurance 3% Increase in Muscular Strength 6% Decrease in Submaximal Heart Rate Visit IgYPerformance.com for details on this ground breaking study Bring this Revolutionary product to your clients with our Earn Up to 50% Profit Contact our sales team for wholesale pricing 888-998-3763 or evan@igynutritioncom IgYPerformance.com PTQ 1.4 | NSCA.COM 25 FEATURE ARTICLE THE SHARED ADAPTATIONS OF THE TRAINING AND REHABILITATION PROCESSES CHARLIE WEINGROFF, DPT, ATC, CSCS R ehabilitation and performance enhancement training are often classified and taught as two distinct processes. In the best-case scenario, the rehabilitation and performance staff work together closely to manage the athlete through the stages of recovery. These situations utilize common communication methods to create an easy transition for an individual that is no longer in need of rehabilitation and may be in need of more advanced performance training for optimal recovery (17). Despite what may appear to be useful teamwork leading to a return to sport and performance training, this sometimes is not the case. In reality, this process is on a continuum that encompasses the same laws of neurological and physiological principles (7,17). Understanding these principles may allow for even further overlap of the rehab and performance training processes leading to potentially quicker results. In the sports rehabilitation and performance field, often “worlds collide” based on semantics and definitions. Many practitioners have a vision of what the rehab and training processes looks like (16). As a common denominator, both processes are about changing the body. Changes in the body’s performance, whether it is movement skills or performance measures can usually be tracked to a common response of adaptation to stress (7). This is known as specific adaptation to imposed demands, or the SAID Principle. When the intent is to change the perception of pain or change motor control, the focus is neurological or neuromuscular, respectively. If the intent is to change or improve measures of flexibility, speed, power, and/or endurance, the focus of the 26 stressor is often neurophysiological or neuroendocrine. Regardless of the goal of the stressor or the designation of the professional, the body is stressed and required to adapt. Viewing the adaptation process through this lens may begin to bring the basic processes of rehab and training much closer together. When viewed through the rehabilitation process, the suggestion is that the body is broken or has negatively adapted to some form of stress (21). The body is injured, and the goal is to restore it to normal levels. This negative stress may be in the form of an ill-advised therapy plan, repetitive motions, overuse syndromes from daily life or fitness activities, or trauma. The stress can be in many different forms, but if the adaptation is not desirable, the individual will often seek medical intervention (7). If the body has responded negatively to stress, one answer to injury prevention is resistance to stress (1,6,8). Some key bodily adaptations can yield resiliency to overloading, overtraining, and certain levels of trauma. Performance training may help improve this resiliency and progress toward injury prevention, if applied properly. Although rarely applied, sometimes it could be beneficial to expedite the rehabilitation process via concurrent application of performance training using movements and exercises that do not exploit the injury or pain (8). These performance training processes manage qualities of the body that are already at normal or above normal levels and aim to create adaptations that are above normal. If the training process intends to restore or improve qualities of the body based on general and specific applications of stress, there would potentially be less discord and improved outcomes in both processes with professionals of both ends of the spectrum working off the same premises and goals. PTQ 1.4 | NSCA.COM Proper stress application is the common thread between rehabilitation and performance training processes, and there is a lot of scientific research behind each field of study. Matching the correct practitioner to the appropriate stage of the training process is less science-based and more philosophical. Changing semantics may help make this process easier. If there is injury, it may be acceptable to say that there has been failure of the body to adapt appropriately at some level (10,15). The failure may be anywhere from a local tissue failure to a general injury or an inability to train or compete. Failure from the performance training process is likely an indicator that the individual’s physical adaptations are not at a high enough level to be successful in competitions of the sport (19,20). There are four potential areas of failure where sport coaches, performance coaches, and healthcare professionals can all be legitimate entry points with the common goal of performance training. The first area for potential injury is the equipment. The equipment being used in sports may be out of date in terms of technology, inappropriately sized, or poorly chosen for the type of surface or weather (14). The second area of concern is one of technical skills. Oftentimes the best technical approach to athletics is one that emphasizes positions of the body that are possible injury mechanisms (4). Other times, simply poorly practiced technique may limit power or cause injury (11). In these areas, the sport coach may be the best individual to modulate the stressors that may potentially lead to injury or limitations in output. The third area of potential failure can be termed “biological power.” It is conventional to suggest that limitations in power, endurance, speed, or mental focus are targets to improve performance. However, as the upper thresholds of these qualities are reached or exceeded, it is very reasonable that individuals may need to resort to poor execution or higher threshold techniques that may create joint wear (1,6,13). While operating under lacticgenerating conditions, and given poor conditioning for the selected sport, the body becomes more susceptible to injury, particularly if acute or prolonged rest is not provided (2). Operating under lactic-generating conditions, and given poor conditioning for the selected sport, the body becomes far more susceptible to injury, particularly if acute or prolonged rest is not provided (2). Any limitations in capacities listed above may lead to compensatory strategies as well as function under unfavorable allostasis for performance or injury. Identifying the ideal joint positions, tonic and phasic muscle function of the sport, allostatic recovery, and the most efficient work capacity are all key management strategies that the healthcare provider and performance coach can apply (4,8,11,13). or ideal sport specificity. In general, movement selection may be less important, but carryover efficiency is more important in training competitive athletes (10,13). While the performance coach may be too aggressive and cause injury via overtraining, the check and balance to this process, for example, may come from the healthcare provider training in manual therapy or other recovery methods that may expedite acute levels of recovery (3,12). No neurological recovery technique can outrun poorly managed physiological training approaches, but in a well-crafted team-based approach, injury may be limited, and performance may be enhanced if executed properly. This is where some rehabilitation techniques are also doubling as recovery techniques (3,12). Using the stress application thought process, injury can be viewed as the recovery process that has gone awry so that there may be pain or compensatory movement strategies, such as autogenic inhibition or tone (21). While the third area of potential injury is traditionally governed by the performance coach, the fourth has more to do with the rehabilitation professional; this area is movement. Simply, when all other categories are exhausted and do not manage the failure of injury or performance, the assumption is that the body simply cannot get into the positions, mechanically or neurologically, to absorb, and adapt to stress appropriately (19). This may require the development of the physiological qualities required to compete, or it may require the neurological acquisition of new motor skills best suited for training or the sport. There are many ways to screen or assess for movement competency and the corrective methods to fix what is found are countless. Techniques that span joint mobility, soft tissue extensibility, and neurological tone are managed by the rehabilitation professional (18,20). These techniques set up the motor acquisition process via applying unique stressors to upregulate proprioception. And it is this proprioception that allows for repetition in the desired form and patterns of training and practicing sport-specific skills (15). Although there is gray area surrounding this topic, it is grounded in the scientific approach of creating desired adaptations via unique and guided applications of stress. There is a recognition that neurological adaptations can be fleeting but exploited where available to develop physiological adaptations. Keen levels of evaluation of movement, biological power, technical skills, and equipment can reveal the best entry point for rehabilitation and performance professionals to work together. Power can be developed, and this falls under the performance coach. Carryover to sport is paramount during training as much as it is important to select volumes and intensities that complement the current status and development of the individual. There is a lot of leeway in training the general population with this in mind; however, training at intensities that far exceed the individual’s current capabilities is a potentially dangerous process. Choosing movements that do not degrade technical proficiency due to lactic energy supply may take a program away from personal preference PTQ 1.4 | NSCA.COM 27 THE SHARED ADAPTATIONS OF THE TRAINING AND REHABILITATION PROCESSES REFERENCES 1. Albright, J, Mcauley, E, Martin, R, Crowley, E, and Foster, D. Head and neck injuries in college football: An eight-year analysis. The American Journal of Sports Medicine 13(3): 147-152, 1985. 2. Baker, JS, McCormick, MC, and Robergs, RA. Interaction among skeletal muscle metabolic energy systems during intense exercise. J Nutr Metab 2010: 905612. doi: 10.1155/2010/905612. Epub 2010. 3. Bang, M, and Deyle, G. Comparison of supervised exercise with and without manual physical therapy for patients with shoulder impingement syndrome. Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy 30(3): 126-137, 2000. 4. Chu, Y, Sell, T, and Lephart, S. The relationship between biomechanical variables and driving performance during the golf swing. Journal of Sports Sciences 28(11): 1251-1259, 2010. 5. Coffin-Zadai, C. Disabling our diagnostic dilemmas. Physical Therapy 87(6): 641-653, 2007. 6. Ekstrand, J, Gillquist, J, Moller, M, Oberg, B, and Liljedahl, S. Incidence of soccer injuries and their relation to training and team success. The American Journal of Sports Medicine 11(2): 63-67, 1983. 7. Finger, M, Cieza, A, Stoll, J, Stucki, G, and Huber, E. Identification of intervention categories for physical therapy, based on the international classification of functioning, disability and health: A Delphi exercise. Physical Therapy 86(9): 1203-1220, 2006. 8. Gabbett, T, and Domrow, N. Relationships between training load, injury, and fitness in sub-elite collision sport athletes. Journal of Sports Sciences 25(13): 1507-1519, 2007. 9. George, SZ, Bialosky, JE, and Fritz, JM. Physical therapist management of a patient with acute low-back pain and elevated fear avoidance beliefs. Phys Ther 84(6): 538-549, 2004. 10. Hodges, PW, and Moseley, GL. Pain and motor control of the lumbopelvic region: Effect and possible mechanisms. J Electromyogr Kinesiol 13(4): 361-70, 2003. 11. Hume, P, Keogh, J, and Reid, D. The role of biomechanics in maximizing distance and accuracy of golf shots. Sports Medicine 35(5): 429-449, 2005. 15. O’Sullivan P. Diagnosis and classification of chronic low-back pain disorders: Maladaptive movement and motor control impairments as underlying mechanism. Man Ther 10(4): 242-55, 2005. 16. Philosophical Statement on the Definition of Physical Therapy (HOD 06–83–03–05). In: House of Delegates Policies. Alexandria, VA: American Physical Therapy Association; 1983. 17. Rose, SJ. Diagnosis: Defining the term Phys Therapy 69(2): 162-163, 1989. 18. Sahrmann, S. Diagnosis and Treatment of Movement Impairment Syndromes. (1st ed.) St Louis, MO: Mosby, Inc.; 2001. 19. Sahrmann, S. Diagnosis by the physical therapist—A prerequisite for treatment. Journal of the American Physical Therapy Association 68(11): 1703-1706, 1988. 20. Scheets, P, Sahrmann, S, and Norton, B. Use of movement system diagnoses in the management of patients with neuromuscular conditions: A multiple-patient case report. Phys Ther 87(6): 654-669, 2007. 21. Simons, DG, and Mense, S. Understanding and measurement of muscle tone as related to clinical muscle pain. Pain 75(1): 1-17, 1998. ABOUT THE AUTHOR Charlie Weingroff is a Doctor of Physical Therapy, Certified Athletic Trainer (ATC), and Certified Strength and Conditioning Specialist® (CSCS®). He spends his time training and rehabbing athletes and clients at Drive495 in New York City, NY and Fit For Life in Marlboro, NJ. He is also an internationally renowned speaker for his own seminar series “Training = Rehab, Rehab = Training,” M-F Athletic, and other various conferences and outlets. Weingroff is the Director of Physical Performance and the Head Strength and Conditioning Coach for the Canadian Men’s National Basketball Team. He also holds a similar position as Director of Performance for the RoddickGrunberg School of Tennis in Ft. Worth, Texas. Positions he has formally held include Head Strength and Conditioning Coach for the Philadelphia 76ers in the National Basketball Association (NBA) and Lead Physical Therapist for the United States Marine Corps Special Operations Command. 12. Jull, G, Trott, P, Potter, H, Zito, G, Niere, K, Shirley, D, Emberson, J, Marschner, I, and Richardson, C. A randomized controlled trial of exercise and manipulative therapy for cervicogenic headache. Spine 27(17): 1835-1843, 2002. 13. Liederbach, M, and Compagno, J. Psychological aspects of fatigue-related injuries in dancers. The Journal of Dance Medicine and Science 5(4): 116-120, 2001. 14. Marshall, S, Waller, A, Dick, R, Pugh, C, Loomis, D, and Chalmers, D. An ecologic study of protective equipment and injury in two contact sports. International Journal of Epidemiology 31(3): 587-592, 2001. 28 PTQ 1.4 | NSCA.COM NSCA.com GETTING THE MOST OUT OF A CERTIFICATION IN PERSONAL TRAINING ROBERT LINKUL, MS, CSCS,*D, NSCA-CPT,*D T he hours that you spent studying and preparing for your certified personal trainer (CPT) certification exam paid off. You are now officially ready to join the work force and bare the “CPT” credentials after your name. These initials indicate to the client that you are an educated professional that can help them achieve their fitness goals. They also indicate to other trainers that you belong among the ranks, but it does not stop there. You can get a lot more out of your certification if you set your standards high and implement these important steps. KEEP IT CURRENT It is unfortunate to think that after all the hours spent to earn a certification that a trainer would let his or her certification expire, but many do. The reasons vary, maybe it is a financial issue or maybe they feel they no longer need it because the standards that they have set for themselves are not high enough. The basic demands of the strength and conditioning industry recommend that a trainer keep up-to-date with first aid and cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) qualifications, as well as maintain a current certification. These are general recommendations, not requirements; the industry does not officially require a trainer to have a certification, and there is no governing body or entity to uphold a high standard for trainers. The only standards are the ones that each individual sets for themselves and it all starts with keeping that hard earned certification(s) current and up-to-date, in which the length can vary between organizations and certifications. The best way to keep a certification current is by obtaining continuing education. Earning continued education units (CEUs) is a mandatory requirement for keeping up most certifications. Conferences, clinics, seminars, webinars, self-studies, home studies, quizzes, book chapters, book reviews, journal articles, journal reviews, secondary certifications, and specialized certifications make up the more popular ways to earn CEUs. The material presented for CEUs in this day and age is exceptional. Research in the strength and conditioning industry is at an all-time high and the information that is coming from these studies has proven to be very beneficial for clients, if implemented correctly by their trainer. Adhering to a high standard and keeping 30 certifications current may allow the trainer to be showcased in a very professional manor and prove to be a valuable asset to the client. SHOWCASING VALUE Oftentimes, one of the first things a potential client does prior to contacting a trainer is research their name on the Internet. The client wants to be assured that they are making the right decision by selecting the individual that has the proper education and experience to help them with their specific needs. Knowing how important this information is to the client, it is even more reason to showcase everything that a trainer has to offer. The trainer’s name, title, and credentials should appear the same way anywhere it is displayed. Business cards, information on the website, content on promotional flyers, and biographies hanging on the wall in the gym should be updated regularly with the most recent information, education, experience, credentials, and areas of expertise. The trainer should take advantage of any chance to inform the client; for example, they could do this by explaining what certain certifications emphasize. Professional branding is a further step that can be taken to showcase a personal trainer’s value over the competition. EDUCATING CLIENTELE It is the trainer’s job to educate clients about fitness. It is also the trainer’s job to educate clients on how to select the right trainer to work with in the first place. One of the best ways to do this is by producing materials that explain what the credentials mean. Explain to clients the requirements that must be met in order to maintain those credentials and the number of hours spent earning CEUs. Another great way to showcase this is to write reviews about conferences or workshops attended and to post pictures at these educational events on the Internet for all to see. If possible, a trainer could allow one day a week in which they wear clothing (e.g., polo shirts, t-shirts, sweatshirts, etc.) of the certifying organization that shows affiliation or certification. You want clients to recognize these organizations and credentials, and to affiliate them with success, education, and professionalism. It is recommended that a trainer make the certifying agency and credentials a common topic in the facility. Additionally, the PTQ 1.4 | NSCA.COM trainer could put up posters, membership stickers, upcoming clinic or conference information, and anything else that will show a professional affiliation with a reputable organization. Not only can the trainer improve the quality of the product this way, but could also help to build a reputation for being an educated fitness professional as well. The product provided to the client and the trainer’s reputation are two products that go hand-in-hand. Providing a quality product to each client will grow a reputation for being an elite trainer, and a high-quality reputation in the industry is a better self-marketing tool then any promotional campaign. Building a quality reputation will earn more business without having to resort to sales pitches or extreme discounts because the client will have already heard of the trainer and his or her successes. Ultimately, this may lead to clients seeking out the best trainers for assistance and when that happens, a trainer who adheres to high standards can reap the rewards of this hard work. The client wants to work with the best and the brightest trainer they can find. All a trainer needs to do is promote himself or herself as that person. A trainer should hold himself or herself to a high standard and keep first aid, CPR, and certification(s) current. A trainer should keep attending conferences and taking advantage of CEU opportunities. In addition, it is important to showcase value by placing an emphasis on elite certification and the organization that hosts it. By doing all these things, a trainer can effectively showcase value to the client and effectively get the most of a certification. REFERENCES 1. Clayton, N. The key to career growth. PFP Magazine. July-August: 10, 2013. 2. Douglas, S. Making the most of your NSCA certification – interview with the 2012 Personal Trainer of the Year. NSCA Career Development Website. 2012. Retrieved 2014 from http://www.nsca. com/Membership/Career-Services/Making-the-Most/. 3. Douglas, S. Boost marketability: Leverage your continuing education. PFP Magazine November-December: 10, 2013. 4. Pettitti, C. Wellness coaching certification: A new frontier for personal trainers in health care. Strength and Conditioning Journal. 35(5): 63-65, 2013. ABOUT THE AUTHOR Robert Linkul is the National Strength and Conditioning Associations (NSCA) 2012 Personal Trainer of the Year and is a volunteer with the NSCA as their Southwest Regional Coordinator and committee chairman for the Personal Trainers Special Interest Group (SIG). Linkul has written for a number of fitness publications including Personal Fitness Professional, Healthy Living Magazine, OnFitness Magazine, and the NSCA’s Performance Training Journal (PTJ). Linkul is an international continued education presenter within the fitness industry and a career development instructor for the National Institute of Personal Training (NPTI). NSCA’s Certified Personal Trainer (NSCA-CPT) Enhanced Online Study Course Master the essentials of personal training Developed by the NSCA and Human Kinetics, this enhanced online study course offers a practical and efficient method of studying for the NSCA-CPT exam, including more than 120 interactive learning activities and real-world applications. An end-of-course exam mimics the scope and difficulty of the actual certification exam. Current NSCA-certified professionals can also earn CEUs by completing this course. National Strength and Conditioning Association Enhanced online course with NSCA’s Essentials of Personal Training, Second Edition book† and exam ©2014 • ISBN 978-1-4504-5869-6 • $269.00 NSCA 1.5 • Eligible for recertification with distinction † Also available as an e-book. If you already own the book, you may purchase the course without the book. Corresponding Text NSCA’s Essentials of Personal Training, Second Edition National Strength and Conditioning Association Jared W. Coburn, PhD, and Moh H. Malek, PhD, Editors ©2012 • Hardback, e-book • 696 pp ISBN 978-0-7360-8415-4 • $96.00 HUMAN KINETICS The Information Leader in Physical Activity & Health PTQ 1.4 | NSCA.COM 31 DEVELOPING THE POTENTIAL OF THE UNDERSERVED CLUB ATHLETE: A PROJECT WITH THE DUKE CLUB HOCKEY TEAM ® REP8VEMRMRK S M X G R Y * R M W 8LI0IEHIV ;IFVMRKXLI FIWXXSKIXLIV 5YEPMX]4VSHYGXW )\GITXMSREP7IVZMGI 8ST2SXGL)HYGEXMSR -RRSZEXMZI'SRWYPXERXW /RS[PIHKIEFPI7XEJJ 'YWXSQ*EGMPMX](IWMKR Call for our new catalog. 800-556-7464 I performbetter.com LIVE | DEC. 17, 2014 HACKING HEALTH SUPPLEMENTS FOR MUSCLE GROWTH, FAT LOSS, AND ATHLETIC PERFORMANCE KAMAL PATEL, MPH, MBA Kamal Patel, the Director of Examine.com, is a nutrition researcher with both a Master’s degree in Public Health and Business Administration from Johns Hopkins University. In this webinar, Kamal will address how general health supplements that support the hormonal, immune and nervous systems are essential to performance in the gym. 32 PTQ 1.4 | NSCA.COM