Age & Transformational Leadership: Motivation & Discretion

advertisement

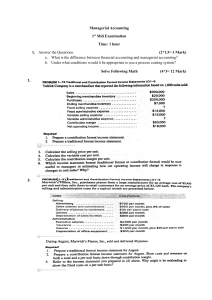

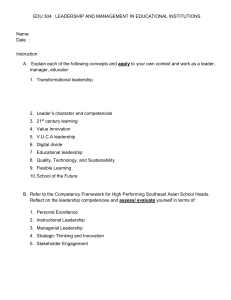

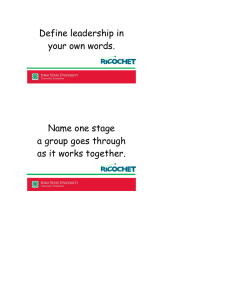

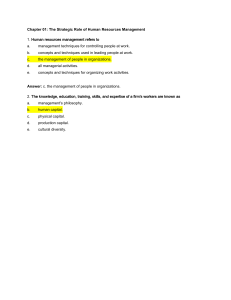

Original Article Age and Transformational Leadership This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly. The Roles of Motivation to Lead and Managerial Discretion Yisheng Peng1, Jie Ma2, Xiaohong Xu3, and Greg Thrasher4 1 Department of Organizational Sciences and Communication, The George Washington University, Washington, DC, USA 2 School of Management, Jinan University, Guangzhou, PR China 3 Department of Management, The University of Texas at San Antonio, TX, USA Department of Management and Marketing, Oakland University, Rochester Hills, MI, USA 4 Abstract: Based on socioemotional selectivity theory, this study examined the indirect relationship between leader’s age and transformational leadership through motivation to lead. This study also investigated managerial discretion as a moderator of the association between age and motivation to lead. A multisourced and two-wave study of 186 Chinese leader–follower dyads shows that leader’s age was indirectly related with transformational leadership through motivation to lead. Managerial discretion moderates the negative age–motivation to lead relationship such that the relationship was significant and negative only for leaders with low managerial discretion. This study provides implications for the management of an increasingly age-diverse workforce and can inform human resource management practices aiming to maximize leadership effectiveness at a later age. Keywords: age, transformational leadership, motivation to lead, managerial discretion Transformational leadership is defined as “moving the follower beyond immediate self-interests through idealized influence (charisma), inspiration, intellectual stimulation, or individualized consideration” (Bass, 1999, p. 11).1 Leaders who display transformational leadership behaviors have the potential to promote followers’ job attitudes (e.g., Judge & Piccolo, 2004) and job performance (e.g., Piccolo & Colquitt, 2006; Wang et al., 2011), as well as organization-level performance (e.g., Judge & Piccolo, 2004; Wang et al., 2011). Given that the population of leaders is growing increasingly age-diverse (Thrasher et al., 2020), there is an increasing interest in understanding the role of age in leadership and finding ways to retain leadership talent (e.g., transformational leadership) across the lifespan (Rudolph, Rauvola, & Zacher, 2018; Walter & Scheibe, 2013; Zacher et al., 2015). It is expected that modern organizations will rely on a body of leaders who, regardless of age, are able to exhibit transformational leadership behaviors. However, research suggests that as 1 individuals age, they may shift their leadership styles in response to a variety of internal (changes in motivation; Thrasher et al., 2020; Zacher, Rosing, Henning, & Frese, 2011) and external age-related changes (age-based social norms; Zacher et al., 2015). To date, very limited research has examined age and transformational leadership. Among the few exceptions, there is little consistency in results. For example, transformational leadership has been found to be more pronounced at older ages (Barbuto et al., 2007), while other unpublished research found a negative relationship between leader’s age and transformational leadership (Van Solinge, 2014). Some research also found a null effect of age on transformational leadership (Ng & Sears, 2012; Zacher, Rosing, & Frese, 2011). The inconsistent results offer little guidance to retaining leadership talent across the lifespan. Scholars suggest that research should delve deeply into why and when age relates to transformational leadership (Ng & Feldman, 2015; Walter & Scheibe, 2013; While readers are likely more familiar with the four-dimensional model by Bass (1999), the present study follows the five-dimensional model by Rafferty and Griffin (2004). This is because other researchers have raised concerns about the lack of theoretical distinctiveness between the four dimensions (Barbuto, 1997; Yukl, 1999). As such, Rafferty and Griffin (2004) have further identified five more focused subdimensions of transformational leadership that are theoretically distinct: visioning, inspirational communication, supportive leadership, intellectual stimulation, and personal recognition. © 2023 Hogrefe Publishing Journal of Personnel Psychology (2024), 23(2), 71–82 https://doi.org/10.1027/1866-5888/a000326 This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly. 72 Zacher, Rosing, & Frese, 2011). The gap in understanding the effect of age on transformational leadership is especially surprising given that the relationally focused and socially constructed nature of leadership (McCauley & Palus, 2021) presents direct theoretical guidance to study the socially driven lifespan developmental changes highlighted in theories of age-related changes in organizational settings. In the current study, we build on the literature on transformational leadership and lifespan development at work to examine individual processes and contextual boundary conditions that affect the relationship between age and transformational leadership. By bridging the gap between the age and leadership literature, we extend emerging theoretical propositions stating that age-related changes in motivations could explain the possible relationship between age and positive leadership behaviors (Hertel et al., 2013; Inceoglu et al., 2012; Kooij et al., 2011; Zacher et al., 2015). These propositions are largely rooted in socioemotional selectivity theory (SST; Carstensen et al., 1999), which states that with age, people tend to be more present-oriented and are less motivated toward future-oriented, knowledge, and development-related goals. Such a weakened tendency to seek future-oriented and agentic goals can orient people less toward dominance and status (Thrasher et al., 2020) and in turn reduce their motivations to take a leadership role and invest time and effort into leading others (i.e., motivation to lead; Chan & Drasgow, 2001). Building on these, the current study first tests whether motivation to lead can explain the age–transformational leadership relationship. Furthermore, because motivation is fundamentally defined by an interaction between personal goal orientations and environmental opportunities and feedback (Klein, 1989; Locke, 1991), we suggest that leaders’ managerial discretion can influence the extent to which age relates to motivation to lead and subsequent transformational leadership behaviors. Managerial discretion refers to the extent to which managers perceive that they can affect important organizational outcomes through various managerial actions (Hambrick & Finkelstein, 1987; Wangrow et al., 2015). Grounded within SST (Carstensen et al., 1999), because managerial discretion can enhance positive emotional experiences and perceived meaningfulness of being a leader, people with high managerial discretion at relatively older ages may still prioritize leadership roles, and thus, their motivation to lead can be sustained. In contrast, those with low managerial discretion at relatively older ages may have weaker motivations to lead because they perceive their leadership roles to be less satisfying, rewarding, and meaningful. Thus, we test a moderated mediation model examining the motivational process (i.e., motivation to lead) and one structural boundary condition (i.e., managerial Journal of Personnel Psychology (2024), 23(2), 71–82 Y. Peng et al., Age and Transformational Leadership discretion) for the age–transformational leadership relationship (see Figure 1). This study contributes to the research on age and leadership in the following ways. First, we introduce SST as the theoretical foundation and test motivation to lead as a mediator between age and transformational leadership, deepening our understanding of the underlying mechanism that links age and transformational leadership (Rudolph, Rauvola, & Zacher, 2018; Thrasher et al., 2020; Walter & Scheibe, 2013). Second, we examine one structural working condition by testing the moderating effect of managerial discretion, providing a potential explanation for the inconsistent findings regarding possible age differences in transformational leadership (Barbuto et al., 2007; Ng & Sears, 2012; Van Solinge, 2014; Zacher, Rosing, & Frese, 2011). Overall, this study extends leadership literature by testing a model that acknowledges the role of person–environment interaction in understanding age and leadership. Age, Motivation to Lead, and Transformational Leadership Motivation to lead affects a “leader’s decisions to assume leadership training, roles, and responsibilities and that affect his or her intensity of effort at leading and persistence as a leader” (Chan & Drasgow, 2001, p. 482). It is an important predictor of leadership emergence (Luria & Berson, 2013), leadership behaviors (Kark & Van Dijk, 2007), and leadership effectiveness (Badura et al., 2020). It should be noted that although motivation to lead is relatively stable over time, it may change due to social learning processes and experiences (Chan & Drasgow, 2001; Kark & Van Dijk, 2007) as well as agerelated changes in physical, cognitive, and socioemotional aspects (Peng et al., 2018). This is especially true given that being in leadership roles may demand an intensive effort at leading and managing other people (Chan & Drasgow, 2001), whereas individuals’ effort and interest in doing so may decline as they age (Kanfer & Ackerman, 2004). Researchers have long applied SST (Carstensen, 1992) to describe age-related socioemotional changes. SST categorizes human goals/motives into two categories, knowledge acquisition and emotion regulation, and proposes that one’s perception of time influences how they assign importance to these goals. As people grow older, they tend to be less motivated toward future-oriented, knowledge, and development-related goals (Carstensen et al., 1999). Specifically, at younger ages, people usually perceive time as open-ended and tend to prioritize knowledge-related goals. With age, people tend to gradually perceive the future as limited (i.e., having less © 2023 Hogrefe Publishing Y. Peng et al., Age and Transformational Leadership 73 This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly. Figure 1. The conceptual model. remaining time), so they give less value to career growth and development-related goals (Lang & Carstensen, 2002). In the workplace, with age, people tend to perceive less remaining time in employment and, importantly, fewer new work-related goals, possibilities, and opportunities in the foreseen future (Rudolph, Kooij, et al., 2018). Thus, it is possible that with age, people tend to focus less on goals that help maximize their career development outcomes, such as becoming a leader. Indeed, it has been found that age is negatively related with strength of growth and extrinsic motives (e.g., promotion; Inceoglu et al., 2012; Kooij et al., 2011). Extrinsic growth values (e.g., advancing one’s career, gaining influence) also decline with age (Hertel et al., 2013). It has also been found that age was related to lower work-related growth motives and lower motivation to continue working through reduced future time perspective (limited remaining time) and promotion focus (Kooij et al., 2014). As to leaders, it has been found that they generally tend to shift away from dominance and agentic goals as they grow older (Thrasher et al., 2020). Although some people may want to lead because leading others may involve enjoyable emotional experiences that allow for building communal bonds, cultivating such pleasant emotions and leader–follower exchange relationships requires a set of effortful behaviors, such as emotional labor (e.g., managing one’s emotions when interacting with followers; Humphrey et al., 2008). Relatedly, findings of previous research suggest that people generally tend to engage in less effortful emotional labor (e.g., intentionally displaying positive emotions) as they grow older (Dahling & Perez, 2010; Peng et al., 2021). Furthermore, because transformational leaders usually need to invest great effort and energy to inspire, excite, and deliver an extraordinary vision to followers (Bass & Avolio, 1993), with age, people may be less motivated to assume leadership roles due to the required effort and energy. As people grow older, they may experience declines in cognitive resources (Peng et al., 2018). Older individuals may face difficulties in cognitively demanding jobs (Peeters & van Emmerik, 2008), and thus, they may have weaker motivations to become a leader if leadership roles require great cognitive efforts. In all, because being a leader may require people to effortfully focus on long-term, visionary © 2023 Hogrefe Publishing goals and specific social and emotional relationships that feature such leadership roles, with age, people may tend to have lower levels of motivation to lead. Hypothesis 1: Leader’s age will be negatively related with motivation to lead. Transformational leaders can positively influence employees through various leadership behaviors (e.g., visioning, intellectual stimulation, etc.; Bass, 1999; Rafferty & Griffin, 2004). Given the important implications of high motivation to lead for individuals’ transformational leadership (Badura et al., 2020; Barbuto, 2005; Gilbert et al., 2016) and leadership effectiveness (Badura et al., 2020; Kirkpatrick & positively relate to transformational leadership. Motivation typically “moves people to act” (Deci & Ryan, 2008, p. 14). In general, people with high motivation to lead would self-set high standards (Chan & Drasgow, 2001). They are more likely to develop idealized influence because they could empower followers and engender the trust and respect of their followers by behaving as a role model. They may also tend to have pride in being the leader, act with integrity, and make sacrifices for the good of the whole team. People with high motivation to lead may also highly commit to their leadership roles and seek to benefit the collective. They tend to create and articulate high expectations and shared visions to motivate and inspire followers. Furthermore, people with high motivation to lead tend to assume leadership positions, not for their own interest, and are thus more likely to be concerned with the wellbeing and development of followers (Bass, 2008). They are more likely to show individualized consideration by treating followers as individuals and helping them meet different needs. They also tend to act in a way that is in accord with the group’s interest and are likely to encourage followers to challenge existing beliefs, involve them in decision-making, and seek their suggestions and ideas. In all, we expect that people with high motivation to lead are more likely to display transformational leadership behaviors because these behaviors could be natural consequences of those people’s positive orientation and desire to assume leadership roles (Badura et al., 2020). Journal of Personnel Psychology (2024), 23(2), 71–82 74 Y. Peng et al., Age and Transformational Leadership Consistent with the theoretical proposition made by SST that as people age, they tend to be less motivated toward future-oriented, knowledge, and development-related goals (Carstensen et al., 1999), we posit that as people grow older, they may be less likely to demonstrate transformational leadership due to declines in their motivations to lead. This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly. Hypothesis 2: Motivation to lead will be positively related with transformational leadership. Hypothesis 3: Leader’s age will be indirectly related with transformational leadership through motivation to lead. The Moderating Role of Managerial Discretion According to SST (Carstensen et al., 1999), with age, people tend to focus more on emotionally positive and meaningful experiences. Because managerial discretion allows leaders to bend leadership roles to their will and personal preferences (Hambrick & Finkelstein, 1987; Wangrow et al., 2015), it brings leaders positive and gratifying experiences. As such, the age–motivation to lead relationship may depend on leaders’ perceived managerial discretion. Specifically, when managerial discretion is high, people have a wide range of options and thus perceive great decision latitude (Wangrow et al., 2015). It enables individuals to use skills and abilities to navigate contextual constraints and effectively influence critical organizational outcomes (López-Cotarelo, 2018). Such discretion is fundamental for creating positive emotions at work (Xanthopoulou et al., 2012). Research has also found that managerial discretion may be particularly helpful when people grow older (Kooij et al., 2011; Zaniboni et al., 2016). As such, managerial discretion may help retain leaders’ motivation to lead at relatively older ages. Although anecdotally people in leadership roles tend to perceive a good amount of managerial discretion at work, some of them may perceive low managerial discretion (relative to others) due to the institutional and organizational contexts that can impose constraints on leaders (Jacobsen, 2022; Yukl, 2013). For instance, in an organization with a flat structure, middle-level leaders may perceive low managerial discretion because there are few levels of management and the authority and power might be shared between the workers and the higher-level leaders. When managerial discretion is low, leaders could experience constraints on their authority to make decisions, which do not grant them with necessary options and actions available to achieve important Journal of Personnel Psychology (2024), 23(2), 71–82 goals at work (Barker et al., 2001). Thus, leaders with low managerial discretion are less likely to experience positive emotions (Xanthopoulou et al., 2012) and more likely to experience negative and aversive experiences at work (Liu et al., 2005). Leaders at relatively older ages may perceive such leadership roles with low managerial discretion as demotivating (Kooij et al., 2011) and thus exhibit a low motivation to lead. With the aforementioned reasoning, it is likely that when managerial discretion is high, the indirect effect of age on transformational leadership via motivation to lead will be weaker. In contrast, when managerial discretion is low, this indirect effect will be stronger. Hypothesis 4: Managerial discretion will moderate the relationship between leader’s age and motivation to lead such that the relationship will be weaker for leaders with high than low managerial discretion. Hypothesis 5: Managerial discretion will moderate the indirect relationship between leader’s age and transformational leadership through motivation to lead such that the indirect relationship will be weaker for leaders with high than low managerial discretion. Methods Participants and Procedure The data collection was conducted in compliance with the ethical guidelines of the American Psychological Association (APA) and was approved by the second author’s affiliated institute. At Time 1, 227 leaders from a large telecom company in Northwest China received a paper survey assessing demographic variables, motivation to lead, and managerial discretion. One month later, another paper survey enclosed in an envelope containing the measure of transformational leadership was sent to a follower under each leader selected by the human resource department. At Time 1, we received 219 responses of the 227 supervisors we invited (a response rate of 96.48%). At Time 2, we received 195 valid responses and successfully linked 186 valid supervisor–employee dyads. On average, leaders were 41.62 years old (SD = 6.91; 32–60 years old). The distribution of age in the sample can be found in Figure 2. As can be seen in Figure 2, the distribution of leader’s age is non-normal (positively skewed), which is very similar to the age distributions of the US workforce (United States Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2022) and the Chinese workforce (China Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2020). Specifically, 92 respondents were 39 years old or younger (49.5%), 63 were between 40 and 49 © 2023 Hogrefe Publishing This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly. Y. Peng et al., Age and Transformational Leadership 75 Figure 2. The distribution of age in the sample. Ninety-two respondents were 39 years old or younger (49.5%), 63 were between 40 and 49 years old (33.9%), 29 were between 50 and 59 years old (15.6%), and two were 60 years old and older (1.1%). years old (33.9%), 29 were between 50 and 59 years old (15.6%), and two were 60 years old and older (1.1%). The job duties of the majority of leaders were executed at the section and division (97.85%) levels but did not involve managing other leaders. All the participants are below the C-suite level. There were 125 males and 61 females, and the average of years in leadership positions was 8.37 (SD = 6.67). Measures Motivation to Lead We used a shortened 15-item version of Chan and Drasgow’s (2001) questionnaire. Participants were asked to indicate the extent to which they agree with each of the statements on a seven-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). A sample item is “I am the type of person who likes to be in charge of others.” Cronbach’s α was .87. Managerial Discretion tBased on previous research (Karasek, 1979; LópezCotarelo, 2018; Wangrow et al., 2015), we measured leaders’ managerial discretion over the following six aspects that are important to leadership and management work: personnel decision-making, budget planning, work-related goal setting, how to perform work, use of organizational resources, and organizational strategic decision-making. Leaders were instructed to indicate the extent to which they perceive managerial discretion in each of the six aspects on a five-point scale (1 = not at all, 5 = very much). The six © 2023 Hogrefe Publishing items used in the current study yielded a single-factor model that had a good model fit [χ2(9) = 11.25, p = .26, CFI = .98, RMSEA = .04 (95% CI = .00–.10), SRMR = .04]. A sample item is “To what extent you perceive managerial discretion in personnel decision-making.” Cronbach’s α was .70. Transformational Leadership Rafferty and Griffin’s (2004) 15-item measure was used to measure transformational leadership via five dimensions: vision, inspirational communication, intellectual stimulation, supportive leadership, and personal recognition. Followers were asked to indicate the extent to which their leaders exhibit transformational leadership behaviors on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 = not at all to 5 = to a very large degree. A sample item is “Has a clear understanding of where we are going.” Cronbach’s α was .86. Control Variables Gender was controlled in the analyses because past research has shown that female leaders tend to be more transformational than male leaders (Eagly et al., 2003). It should be noted that excluding this control variable did not affect the results for all our hypothesized relationships. Analytic Strategies Path modeling was used to test the hypotheses via Mplus 7.1 (Muthén & Muthén, 2012). To yield greater precision of estimates and facilitate the interpretation of the unstandardized coefficients for age in comparison with the other unstandardized coefficients in our statistical analyses, we Journal of Personnel Psychology (2024), 23(2), 71–82 76 Y. Peng et al., Age and Transformational Leadership Table 1. Descriptive statistics, reliabilities, and correlations Variables M SD Range 1 41.62 6.91 32–60 — 2. Gendera .33 0.47 0–1 .03 1. Age 2 3 4 5 — 3. Managerial discretion 5.57 0.67 1–7 .05 .06 (.70) — 4. Motivation to lead 5.08 0.79 1–7 .18** .07 .59** (.87) — 5. Transformational leadership 3.88 0.47 1–5 .02 .09 .21** .28** (.86) This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly. Note. N = 186. Diagonal values represent internal consistency for each measure where applicable. aGender was coded as 0 = male and 1 = female. *p < .05. **p < .01. rescaled age by a factor of 10 (Fasbender et al., 2020; Gielnik et al., 2018). Basically, after rescaling age by a factor of 10, all effects including age could be interpreted as for every 10year increase in age a relative change in Y was observed. Results Table 1 provides means, SDs, and correlations among all study variables. Before testing the hypotheses, we performed CFAs to examine the distinctiveness of the study variables. We used dimensional scores for transformational leadership and motivation to lead to model their respective latent constructs. The results show that the three-factor (i.e., motivation to lead, managerial discretion, and transformational leadership) measurement model fitted the data well: χ2(74) = 84.77, p = .18, CFI = .98, RMSEA = .03 (95% CI = .00–.05), SRMR = .05. Compared with a two-factor (i.e., managerial discretion and transformational leadership were combined into one factor) Model 1 [χ2(76) = 283.86, p < .001, CFI = .65, RMSEA = .12 (95% CI = .11–.14), SRMR = .13], a two-factor (i.e., motivation to lead and managerial discretion were combined into one factor) Model 2 [χ2(76) = 101.36, p = .03, CFI = .96, RMSEA = .04 (95% CI = .02–.06), SRMR = .06], a two-factor (i.e., motivation to lead and transformational leadership were combined into one factor) Model 3 [χ2(76) = 263.91, p < .001, CFI = .68, RMSEA = .12 (95% CI = .10–.13), SRMR = .13], and a single-factor model [χ2(77) = 315.25, p < .001, CFI = .60, RMSEA = .13 (95% CI = .11–.14), SRMR = .12], the hypothesized three-factor model had the best model fit. A moderated mediation model, which included the interaction effects of age and managerial discretion on motivation to lead, was tested via path modeling analyses. This model has a good model fit: χ2(4) = 0.91, p = .92, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA = .00 (95% CI = .00–.04), SRMR = .02. We also tested an alternative model including a direct effect between age and transformational leadership. This alternative model also has good fit: χ2(3) = 0.75, p = .86, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA = .00 [95% CI = .00–.07]. The results found that the direct effect of leader’s age on transformational Journal of Personnel Psychology (2024), 23(2), 71–82 leadership was not significant (B = .02, SE = .05, p = .68). Because the model excluding this direct effect did not significantly differ from this model [Δχ2(1) = .18, ns], suggesting that the model without a direct effect was more parsimonious and satisfactory. Table 2 and Figure 1 present the path coefficients of the hypothesized relationships. As shown in Figure 1, age was negatively related with motivation to lead (B = .15, SE = .07, p = .04). Motivation to lead was positively related with transformational leadership (B = .17, SE = .04, p < .01). To test the indirect relationship between age and transformational leadership through motivation to lead, we used the Bayesian approach. Compared to the traditional approaches (e.g., Sobel test, bootstrapping), Bayesian estimation neither requires nor assumes normal distributions of indirect effects (Yuan & MacKinnon, 2009). The Bayesian analysis also has much less chance to exhibit Type I error when the sample size is small (Koopman et al., 2015). Additionally, the interpretation of the confidence interval computed by Bayesian analysis is more straightforward. A 95% credibility interval means that there is a 95% probability that the interval includes the true population mean based on the observed data. The results found that leader’s age was indirectly related with transformational leadership through motivation to lead (IE = .03, 95% CI = .06 to .01). Thus, Hypotheses 1–3 were supported. The interaction between age and managerial discretion was significantly related to motivation to lead (B = .28, SE = .13, p = .03), explaining an additional 2.40% of the variance in motivation to lead. Supporting Hypothesis 4, the results of simple slope tests further showed that when managerial discretion was low (1 SD below the mean), age was negatively related to motivation to lead (B = .34, SE = .11, p = .002). When managerial discretion was high (1 SD above the mean), this relationship was not significant (B = .03, SE = .12, p = .78). We plotted this interaction effect in Figure 3. Furthermore, supporting Hypothesis 5, at low levels of managerial discretion, age had a significant, negative relationship with transformational leadership through motivation to lead (IE = .06, 95% CI = .10 to .03). However, at high levels of managerial discretion, this indirect relationship was not significant (IE = .01, 95% CI = .04 to .04). © 2023 Hogrefe Publishing Y. Peng et al., Age and Transformational Leadership 77 Table 2. Path coefficients of multilevel path modeling analyses Dependent variables Predictors Motivation to lead Leader’s age .15 (.07)* Managerial discretion .69 (.08)** Leader’s age × Managerial discretion .28 (.13)* Transformational leadership Motivation to lead .17 (.04)* Gender .11 (.07) The indirect and conditional indirect effects Estimate Bayesian 95% CI This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly. Leader’s age → Motivation to lead → Transformational leadership Indirect effect .03 [ .06, .01] The conditional indirect effect at high managerial discretion (+1SD) .01 [ .04, .04] The conditional indirect effect at low managerial discretion ( 1SD) .06 [ .10, .03] Note. N = 186. The coefficient estimates were unstandardized and the standard error for the coefficient is in parentheses. *p < .05. **p < .01. Figure 3. The moderating effect of managerial discretion on the relationship between leader’s age and motivation to lead. Sensitivity Analyses To provide further support for our proposed model, we tested a model to include tenure as a competing predictor/control variable for the hypothesized relationship (Bohlmann et al., 2018). The model fit indices were χ2(5) = 1.01, p = .96, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA = .00, SRMR = .02. The results found that leader’s age was still negatively related with motivation to lead (B = .36, SE = .14, p < .01) and managerial discretion significantly interacted with leader’s age in predicting motivation to lead (B = .28, SE = .13, p = .03). However, tenure was not significantly related with motivation to lead (B = .08, SE = .07, p = .26). mechanism and one boundary condition pertaining to the environmental context (i.e., managerial discretion). In a group of 186 Chinese leaders with multisourced data using a time-lagged research design, we found that age was indirectly related to transformational leadership via motivation to lead. Managerial discretion moderated the negative relationship between age and motivation to lead such that the relationship was significant only for leaders with low managerial discretion. Additionally, managerial discretion moderated the indirect relationship such that the indirect relationship between age and transformational leadership via motivation to lead was significant only for leaders with low managerial discretion. Theoretical Implications Discussion We tested a model of age and transformational leadership that included both motivation to lead as a mediating © 2023 Hogrefe Publishing The current research has meaningful theoretical implications for the leadership literature. Although scholars have suggested more than 30 years ago that allocating more attention to age and leadership can significantly Journal of Personnel Psychology (2024), 23(2), 71–82 This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly. 78 benefit leadership research given the aging trend in the workplace (Avolio & Gibbons, 1988), to date, our understanding of the age–leadership relationship is limited. This study adds to these initial attempts to empirically investigate mediating mechanisms underlying the relationship between age and transformational leadership. Extending past research examining potential age differences in transformational leadership behaviors, we proposed and tested motivation to lead as a mediating mechanism underlying the relationship between age and transformational leadership. Our finding highlights the important role of motivation to lead in explicating the indirect association between age and transformational leadership. This study demonstrates managerial discretion as an important boundary condition for the associations between age, motivation to lead, and transformational leadership. Given the complexity of the relationships between age and leadership behaviors (Walter & Scheibe, 2013), there might be various intervening factors involved in this relationship. Our finding suggests that when managerial discretion is low, motivation to lead suffers more for those at older ages than those at relatively younger ages. Consistent with the rationale in previous research (Deci & Ryan, 2000; Xanthopoulou et al., 2012), with age, people may perceive leadership roles with low managerial discretion as demotivating (Kooij et al., 2011) because low managerial discretion may not lead to gratifying and meaningful experiences (Deci & Ryan, 2000; Xanthopoulou et al., 2012). Instead, they may tend to prioritize leadership roles and sustain motivation to lead when managerial discretion is high as high managerial discretion may help them acquire emotionally positive and meaningful experiences from leadership roles. It should be noted, though, that the current study did not directly test these age-related changes as suggested by SST (Carstensen et al., 1999). Future research may consider empirically examining these age-related changes as part of the moderation effect of managerial discretion on the age–motivation to lead relationship. Extending previous research focusing on whether there are age-related differential effects of managerial discretion (Ng & Feldman, 2015; Zaniboni et al., 2016), our results provide an interesting perspective showing that motivation to lead may actually suffer more from low managerial discretion for those at relatively older ages. Perhaps when perceiving low discretion in leadership roles, people at relatively older ages are likely to be less motivated to lead (e.g., less likely to be a leader) because motivation to lead reflects individuals’ strive for achievement-related goals that require a lot of personal resources (Inceoglu et al., 2012). Journal of Personnel Psychology (2024), 23(2), 71–82 Y. Peng et al., Age and Transformational Leadership Furthermore, although past research has suggested that managerial discretion could enhance leaders’ influence on their organizations (Crossland & Hambrick, 2011; Hambrick & Finkelstein, 1987), it is still unclear why it matters to organizations. This study offers empirical evidence from the leadership process perspective showing the significant role of managerial discretion in retaining leader’s motivation to lead. Our findings emphasize managerial discretion as an important work contextual factor that has significant implications for leadership behaviors during later working life (e.g., Ng et al., 2008). The results of ancillary sensitivity analyses confirmed that age was negatively related with motivation to lead, above and beyond the effect of tenure. This observation shows that our research model was robust to job tenure. It suggests that the effect of age on motivation to lead (as well as its interaction effect with managerial discretion) was not purely a function of the number of years working in a job. It is very likely that people’s motivation to lead may not necessarily decline as the number of years working in a job increases. Rather, because age itself only serves as an umbrella construct that is intertwined with the passage of time (Peng et al., 2020), it might be due to individuals’ aging experiences as they grow older. Because the major theory used in the current research is SST, which primarily focuses on agerelated, cognitive-motivational changes throughout the lifespan (Rudolph, Kooij, et al., 2018), future research may consider testing the roles of relevant age-related changes in explaining the age–motivation to lead relationship. Practical Implications Beyond the above theoretical implications, this research also has practical implications. When planning for leadership development and talent resources, practitioners should also be aware of the role of managerial discretion in compensating for age-related declines in motivation to lead. Organizations’ succession planning should recognize that one’s motivation to lead may decline as one grows older when managerial discretion is low. As a further note for practitioners to help maintain or even increase employees’ motivation to lead at older ages, we suggest that organizations should recognize the motivating potential of managerial discretion in retaining and strengthening older leaders’ motivation to lead. To promote motivation to lead and encourage transformational leadership behaviors during later working life, organizational practitioners should increase managerial discretion by enabling individuals to access various managerial actions available in deciding their management work and influencing organizational outcomes (Wangrow et al., 2015). © 2023 Hogrefe Publishing Y. Peng et al., Age and Transformational Leadership This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly. Limitations and Future Research The strengths of this study included the use of multisource data from both leaders and followers. However, while this study advances knowledge on age and leadership, the results should be interpreted in light of some limitations. First, the reliance on cross-sectional data does not allow conclusions regarding causality. The observed age effects could be confounded with the cohort (generation) effect (Rudolph, Rauvola, & Zacher, 2018; Salthouse, 2013). A longitudinal design may help examine the relationship between age and transformational leadership from a truly developmental perspective. Furthermore, as our data were collected from a single company, the moderation effect of managerial discretion could be suffered from range restrictions given that managerial discretion is greatly affected by organizationlevel factors (Wangrow et al., 2015). In other words, the real effect of managerial discretion might be even larger than what we found. Relatedly, being in a leadership role usually grants this person a good amount of managerial discretion at work. As such, there might be a possible ceiling effect in our sample. Thus, future research may examine managerial discretion among employees from a variety of different organizations and recruit a sample of leaders that may have more variations in perceived managerial discretion. Another limitation is that the present study only examined transformational leadership but no other types of leadership behaviors, and thus, it may not necessarily be a negative consequence if people had a lower motivation to lead and engaged in less transformational leadership (with low managerial discretion at older ages). Without empirically measuring other types of both positive (e.g., authentic) and negative (e.g., laissez-faire) leadership behaviors, it would be unclear if they would engage in more negative or ineffective leadership behaviors or, instead, more positive and effective leadership behaviors. Future research should consider measuring additional types of leadership behaviors to examine if the shift away from transformational leadership is truly detrimental, versus a situation of merely adopting other positive leader behaviors instead. Although we focused on maximizing older individuals’ own career development outcomes when explaining why older leaders tend to have a lower motivation to lead, it is likely that older individuals may have a different motivation such as a stronger generativity motivation (i.e., one’s inner desire to support and guide younger people and to benefit “future generations”; Doerwald et al., 2021; Kooij & Van De Voorde, 2011), which may relate to other different leadership styles other than transformational leadership. Due to their emphasis on generativity, they may have stronger inner desires to support and guide younger people © 2023 Hogrefe Publishing 79 and to benefit future generations than younger individuals. Future research may consider investigating whether older leaders tend to develop certain types of leadership behaviors such as servant leadership (van Dierendonck, 2011) to promote/develop younger colleagues. The current study was conducted in China, which brings the concern that the findings may not be generalized to leaders in the West. It is unclear whether specific features of Chinese culture (e.g., power distance) may influence the results. We encourage researchers to conduct a crosscultural study to further examine the generalizability of our findings. Future research may also consider extending our theoretical model by encompassing other important leadership outcomes (e.g., effectiveness) and organizational outcomes. It should be noted that the magnitudes of the effect sizes found in the present study were relatively small, which may raise concerns about the practical significance. However, as noted by other scholars, it is not uncommon to find such similar magnitudes of the effect sizes of the indirect effects and/or moderation effects. For instance, Thrasher et al. (2020) reported a similar magnitude (i.e., effect = .04) of the indirect effect of leader’s age and relational-oriented leadership behaviors through amicability (one’s tendency to focus on positive aspects and develop positive social relationships). Like the magnitude of the interaction effect (i.e., 2.4% of variance) found in the present study, it is also common to find interactions accounting for 1%–3% of the criterion variance in field studies (e.g., McClelland & Judd, 1993). Due to the importance of leadership and its effectiveness in nowadays organizations, billions of dollars are invested in leadership developmental efforts each year (Badura et al., 2022; SHRM, 2017). Given its significant implications for leader emergence and leadership behaviors and effectiveness (Badura et al., 2020), we believe that the interpretation of even a small effect-size interaction effect on motivation to lead could have important practical implications. Despite our effort in recruiting a representative sample with appropriate numbers of leaders from different age groups (especially those closer to retirement), our study sample might still be limited due to the range restriction of leader’s age. It is likely that the relationship between leader’s age and motivation to lead was underestimated due to the positively skewed age distribution (i.e., more young and middle-aged and fewer older participants; Bohlmann et al., 2018). The generalization of our findings may be limited because the average leader’s age in the current sample was relatively young. Future research should recruit a sample with a wider age range and an appropriate number of leaders at an older age to more accurately estimate the effect sizes of the hypothesized relationships. Journal of Personnel Psychology (2024), 23(2), 71–82 This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly. 80 Finally, future research may examine other possible contextual moderators of the age–motivation to lead relationship. For instance, Walter and Scheibe (2013) discussed job-related cognitive and emotional demands as possible contextual moderators. It is likely that in addition to managerial discretion perceived by leaders, people may also perceive various levels of cognitive and emotional demands at work, which may moderate the relationship between leader age and motivation to lead. In conclusion, this research not only shows that motivation to lead can explain why as leaders get older they may engage in less transformational leadership but also increases our understanding of the role of managerial discretion in the effect of age on motivation to lead. Our findings highlight that motivation to lead could interact with the environmental context in contributing to individuals’ leadership development across the lifespan. References Avolio, B. J., & Gibbons, T. C. (1988). Developing transformational leaders: A life span approach. In J. A. Conger, & R. N. Kanungo (Eds.), Charismatic leadership: The elusive factor in organizational effectiveness (pp. 276–308). Jossey Bass. Badura, K. L., Galvin, B. M., & Lee, M. Y. (2022). Leadership emergence: An integrative review. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 107(11), 2069–2100. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000997 Badura, K. L., Grijalva, E., Galvin, B. M., Owens, B. P., & Joseph, D. L. (2020). Motivation to lead: A meta-analysis and distal-proximal model of motivation and leadership. Journal of Applied Psychology, 105(4), 331–354. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000439 Barbuto, J. E. (1997). Taking the charisma out of transformational leadership. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality, 12(3), 689–697. Barbuto, J. E., Jr (2005). Motivation and transactional, charismatic, and transformational leadership: A test of antecedents. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 11(4), 26–40. https://doi. org/10.1177/107179190501100403 Barbuto, J. E., Fritz, S. M., Matkin, G. S., & Marx, D. B. (2007). Effects of gender, education, and age upon leaders’ use of influence tactics and full range leadership behaviors. Sex Roles, 56(1), 71–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-006-9152-6 Barker, V. L., III, Patterson, P. W., Jr, & Mueller, G. C. (2001). Organizational causes and strategic consequences of the extent of top management team replacement during turnaround attempts. Journal of Management Studies, 38(2), 235–270. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6486.00235 Bass, B. M. (1999). Two decades of research and development in transformational leadership. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 8(1), 9–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 135943299398410 Bass, B. M. (Ed.). (2008). The Bass handbook of leadership: Theory, research, and managerial applications. Free Press. Bass, B. M., & Avolio, B. J. (1993). Transformational leadership and organizational culture. Public Administration Quarterly, 17(1), 112–121. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40862298 Bohlmann, C., Rudolph, C. W., & Zacher, H. (2018). Methodological recommendations to move research on work and aging forward. Journal of Personnel Psychology (2024), 23(2), 71–82 Y. Peng et al., Age and Transformational Leadership Work, Aging and Retirement, 4(3), 225–237. https://doi.org/10. 1093/workar/wax023 Carstensen, L. L., (1992). Social and emotional patterns in adulthood: Support for socioemotional selectivity theory. Psychology and Aging, 7(3), 331–338. https://doi.org/10.1037/0882-7974.7.3.331 Carstensen, L. L., Isaacowitz, D. M., & Charles, S. T. (1999). Taking time seriously: A theory of socioemotional selectivity. The American Psychologist, 54(3), 165–181. https://doi.org/10.1037/ 0003-066x.54.3.165 Chan, K. Y., & Drasgow, F. (2001). Toward a theory of individual differences and leadership: Understanding the motivation to lead. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 481–498. https:// doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.481 China Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2020). [Title not available]. https://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/pcsj/rkpc/7rp/zk/indexce.htm. Accessed 25 August 2022. Crossland, C., & Hambrick, D. C. (2011). Differences in managerial discretion across countries: How nation-level institutions affect the degree to which CEOs matter. Strategic Management Journal, 32(8), 797–819. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.913 Dahling, J. J., & Perez, L. A. (2010). Older worker, different actor? Linking age and emotional labor strategies. Personality and Individual Differences, 48(5), 574–578. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. paid.2009.12.009 Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. https://doi.org/10.1207/ s15327965pli1104_01 Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2008). Facilitating optimal motivation and psychological well-being across life’s domains. Canadian Psychology / Psychologie canadienne, 49(1), 14–23. https://doi.org/ 10.1037/0708-5591.49.1.14 Doerwald, F., Zacher, H., Van Yperen, N. W., & Scheibe, S., (2021). Generativity at work: A meta-analysis. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 125, Article 103521. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2020. 103521 Eagly, A. H., Johannesen-Schmidt, M. C., & van Engen, M. L. (2003). Transformational, transactional, and laissez-faire leadership styles: A meta-analysis comparing women and men. Psychological Bulletin, 129(4) 569–591. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.4.569 Fasbender, U., Burmeister, A., & Wang, M. (2020). Motivated to be socially mindful: Explaining age differences in the effect of employees’ contact quality with coworkers on their coworker support. Personnel Psychology, 73(3), 407–430. https://doi.org/ 10.1111/peps.12359 Gielnik, M. M., Zacher, H., & Wang, M. (2018). Age in the entrepreneurial process: The role of future time perspective and prior entrepreneurial experience. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 103(10), 1067–1085. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000322 Gilbert, S., Horsman, P., & Kelloway, E. K. (2016). The motivation for transformational leadership scale. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 37(2), 158–180. https://doi.org/10.1108/ lodj-05-2014-0086 Hambrick, D. C., & Finkelstein, S. (1987). Managerial discretion: A bridge between polar views of organizational outcomes. Research in Organizational Behavior, 9, 369–406. Hertel, G., Thielgen, M., Rauschenbach, C., Grube, A., StamovRoßnagel, C., & Krumm, S. (2013). Age differences in motivation and stress at work. In C. M. Schlick, E. Frieling, & J. Wegge (Eds.), Age-differentiated work systems (pp. 119–147). Springer. https:// doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-35057-3_6 Humphrey, R. H., Pollack, J. M., & Hawver, T. (2008). Leading with emotional labor. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 23(2), 151–168. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940810850790 Inceoglu, I., Segers, J., & Bartram, D. (2012). Age-related differences in work motivation. Journal of Occupational and © 2023 Hogrefe Publishing This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly. Y. Peng et al., Age and Transformational Leadership Organizational Psychology, 85(4), 300–329. https://doi.org/10. 1111/j.2044-8325.2011.02035.x Jacobsen, D. I. (2022). Room for leadership? A comparison of perceived managerial job autonomy in public, private and hybrid organizations. International Public Management Journal. Advance online publication. Judge, T. A., & Piccolo, R. F. (2004). Transformational and transactional leadership: A meta-analytic test of their relative validity. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 89(5), 755–768. https://doi. org/10.1037/0021-9010.89.5.755 Kanfer, R., & Ackerman, P. L. (2004). Aging, adult development, and work motivation. The Academy of Management Review, 29(3), 440–458. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2004.13670969 Karasek, R. A. (1979). Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: Implications for job redesign. Administrative Science Quarterly, 24(2), 285–308. https://doi.org/10.2307/ 2392498 Kark, R., & Van Dijk, D. (2007). Motivation to lead, motivation to follow: The role of the self-regulatory focus in leadership processes. The Academy of Management Review, 32(2), 500–528. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2007.24351846 Klein, H. J. (1989). An integrated control theory model of work motivation. The Academy of Management Review, 14(2), 150–172. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1989.4282072 Kooij, D., & Van De Voorde, K. (2011). How changes in subjective general health predict future time perspective, and development and generativity motives over the lifespan. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 84(2), 228–247. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8325.2010.02012.x Kooij, D. T., De Lange, A. H., Jansen, P. G., Kanfer, R., & Dikkers, J. S. (2011). Age and work-related motives: Results of a meta-analysis. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 32(2), 197–225. https://doi. org/10.1002/job.665 Kooij, D. T. A. M., Bal, P. M., & Kanfer, R. (2014). Future time perspective and promotion focus as determinants of intraindividual change in work motivation. Psychology and Aging, 29(2), 319–328. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036768 Koopman, J., Howe, M., Hollenbeck, J. R., & Sin, H.-p. (2015). Small sample mediation testing: Misplaced confidence in bootstrapped confidence intervals. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(1), 194–202. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036635 Lang, F. R., & Carstensen, L. L. (2002). Time counts: Future time perspective, goals, and social relationships. Psychology and Aging, 17(1), 125–139. https://doi.org/10.1037/0882-7974.17.1. 125 Liu, C., Spector, P., & Jex, S. (2005). The relation of job control with job strains: A comparison of multiple data sources. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 78(3), 325–336. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317905x26002 Locke, E. A. (1991). Goal theory vs. control theory: Contrasting approaches to understanding work motivation. Motivation and Emotion, 15, 9–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00991473 López-Cotarelo, J. (2018). Line managers and HRM: A managerial discretion perspective. Human Resource Management Journal, 28(2), 255–271. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12176 Luria, G., & Berson, Y. (2013). How do leadership motives affect informal and formal leadership emergence? Journal of Organizational Behavior, 34(7), 995–1015. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1836 McCauley, C. D., & Palus, C. J. (2021). Developing the theory and practice of leadership development: A relational view. The Leadership Quarterly, 32(2), Article 101456 https://doi.org/10. 1016/j.leaqua.2020.101456 McClelland, G. H., & Judd, C. M. (1993). Statistical difficulties of detecting interactions and moderator effects. Psychological Bulletin, 114(2), 376–390. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.114.2.376 © 2023 Hogrefe Publishing 81 Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2012). Mplus 7.1 [Computer program]. Ng, E. S., & Sears, G. J. (2012). CEO leadership styles and the implementation of organizational diversity practices: Moderating effects of social values and age. Journal of Business Ethics, 105(1), 41–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-011-0933-7 Ng, K.-Y., Ang, S., & Chan, K.-Y. (2008). Personality and leader effectiveness: A moderated mediation model of leadership selfefficacy, job demands, and job autonomy. The Journal Of applied Psychology, 93(4), 733–743. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010. 93.4.733 Ng, T. W., & Feldman, D. C. (2015). The moderating effects of age in the relationships of job autonomy to work outcomes. Work, Aging and Retirement, 1(1), 64–78. https://doi.org/10.1093/ workar/wau003 Peeters, M. C., & van Emmerik, H. (2008). An introduction to the work and well-being of older workers. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 23(4), 353–363. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940810869006 Peng, Y., Jex, S. M., & Wang, M. (2018). Aging and occupational health. In K. Shultz & G. Adams (Eds.), Aging and work in the 21st century (2nd ed., pp. 213–233). Routledge. https://doi.org/10. 4324/9781315167602-10 Peng, Y., Ma, J., Zhang, W., & Jex, S. (2021). Older and less deviant? The paths through emotional labor and organizational cynicism. Work, Aging and Retirement, 7(1), 20–30. https://doi.org/10.1093/ workar/waaa017 Peng, Y., Xu, X., & Matthews, R. (2020). Older and less deviant reactions to abusive supervision? A moderated mediation model of age and cognitive reappraisal. Work, Aging and Retirement, 6(3), 195–205. https://doi.org/10.1093/workar/waaa006 Piccolo, R. F., & Colquitt, J. A. (2006). Transformational leadership and job behaviors: The mediating role of core job characteristics. Academy of Management Journal, 49(2), 327–340. https:// doi.org/10.5465/amj.2006.20786079 Rafferty, A. E., & Griffin, M. A. (2004). Dimensions of transformational leadership: Conceptual and empirical extensions. The Leadership Quarterly, 15(3), 329–354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. leaqua.2004.02.009 Rudolph, C. W., Kooij, D. T., Rauvola, R. S., & Zacher, H. (2018). Occupational future time perspective: A meta-analysis of antecedents and outcomes. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 39(2), 229–248. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2264 Rudolph, C. W., Rauvola, R. S., & Zacher, H. (2018). Leadership and generations at work: A critical review. The Leadership Quarterly, 29(1), 44–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2017.09.004 Salthouse, T. A. (2013). Within-cohort age-related differences in cognitive functioning. Psychological Science, 24(2), 123–130. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797612450 SHRM. (2017). SHRM research overview: Leadership development. https://www.shrm.org/hr-today/trends-and-forecasting/specialreports-and-expert-views/Documents/17-0396%20Research% 20Overview%20Leadership%20Development%20FNL.pdf Thrasher, G. R., Biermeier-Hanson, B., & Dickson, M. W. (2020). Getting old at the top: The role of agentic and communal orientations in the relationship between age and follower perceptions of leadership behaviors and outcomes. Work, Aging and Retirement, 6(1), 46–58. https://doi.org/10.1093/workar/waz012 United States Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2022). Civilian labor force by age, sex, race, and ethnicity. https://www.bls.gov/emp/ tables/civilian-labor-force-summary.htm van Dierendonck, D. (2011). Servant leadership: A review and synthesis. Journal of Management, 37(4), 1228–1261. https://doi. org/10.1177/0149206310380462 Van Solinge, S. W. (2014). Are older leaders less transformational? The role of age for transformational leadership from the Journal of Personnel Psychology (2024), 23(2), 71–82 This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly. 82 perspective of socioemotional selectivity theory [Master’s thesis]. University of Groningen. Walter, F., & Scheibe, S. (2013). A literature review and emotionbased model of age and leadership: New directions for the trait approach. The Leadership Quarterly, 24(6), 882–901. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2013.10.003 Wang, G., Oh, I. S., Courtright, S. H., & Colbert, A. E. (2011). Transformational leadership and performance across criteria and levels: A meta-analytic review of 25 years of research. Group & Organization Management, 36(2), 223–270, https://doi.org/10. 1177/1059601111401 Wangrow, D. B., Schepker, D. J., & Barker III, V. L. (2015). Managerial discretion. Journal of Management, 41(1), 99–135. https://doi. org/10.1177/0149206314554214 Xanthopoulou, D., Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2012). A diary study on the happy worker: How job resources relate to positive emotions and personal resources. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 21(4), 489–517. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432x.2011.584386 Yuan, Y., & MacKinnon, D. P. (2009). Bayesian mediation analysis. Psychological Methods, 14(4), 301–322. https://doi.org/10.1037/ a0016972 Yukl, G. (1999). An evaluation of conceptual weaknesses in transformational and charismatic leadership theories. The Leadership Quarterly, 10(2), 285–305. https://doi.org/10.1016/ s1048-9843(99)00013-2 Yukl, G. (2013). Leadership in organizations (8th ed.). Pearson Education Limited. Zacher, H., Clark, M., Anderson, E. C., & Ayoko, O. B. (2015). A lifespan perspective on leadership. In P. M. Bal, D. T. A. M. Kooij, & D. M. Rousseau (Eds.), Aging workers and the employeeemployer relationship (pp. 87–104). Springer. https://doi.org/ 10.1007/978-3-319-08007-9_6 Journal of Personnel Psychology (2024), 23(2), 71–82 Y. Peng et al., Age and Transformational Leadership Zacher, H., Rosing, K., & Frese, M. (2011). Age and leadership: The moderating role of legacy beliefs. The Leadership Quarterly, 22(1), 43–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua. 2010.12.006 Zacher, H., Rosing, K., Henning, T., & Frese, M. (2011). Establishing the next generation at work: Leader generativity as a moderator of the relationships between leader age, leader-member exchange, and leadership success. Psychology and Aging, 26(1), 241–252. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021429 Zaniboni, S., Truxillo, D. M., Rineer, J. R., Bodner, T. E., Hammer, L. B., & Krainer, M. Decision authority, job satisfaction, and mental health: A study of construction workers. Workar, 2(4), 428–435. https://doi.org/10.1093/workar/waw006 History Received January 22, 2022 Revision received January 30, 2023 Accepted February 27, 2023 Published online August 9, 2023 Publication Ethics The data collection was conducted in compliance with the ethical guidelines of the American Psychological Association (APA) and was approved by the second author’s affiliated institute (Jinan University, Guangzhou, PR China). Yisheng Peng Department of Organizational Sciences and Communication The George Washington University 600 21st Street Northwest Washington, DC 20052 USA yishengpeng@gwu.edu © 2023 Hogrefe Publishing