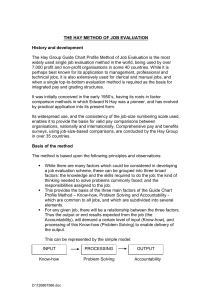

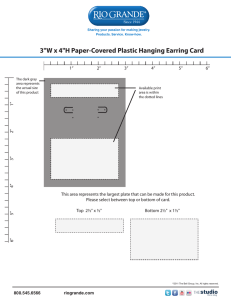

THE VALUATION OF KNOW-HOW Roberto Moro Visconti – Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Milan, Italy roberto.moro@unicatt.it Abstract The know-how expresses the concept of "know-how", straddling the organization in series and technology, legally protected as an industrial secret. The sharing and transferability of know-how is the basis of its economic appraisal, which is based on complementary methodologies projecting the future usefulness of the costs incurred, the relief from royalties by the license or the differential income from internal exploitation. Unlike patents, the know-how is not independently negotiable and is more difficult to enforce against third parties, but at the same time it retains some characteristics of confidentiality that with the patenting in part must be disclosed. Keywords: product innovation; process innovation; patent; R&D; industrial secret; intangibles; technology. 1. The uncertain perimeter of “know-how”, between organization and technology The know-how to do it is a concept characterized by a very broad perimeter of definition, which risks to encroach on the indeterminacy; complex are the problems of application and interpretation, even in the phase of drafting contracts and protection (moral and patrimonial) of rights, primarily in the field of technology transfer or unfair competition. "Know-how’' means a wealth of non-patented practical information, resulting from experience and testing by the supplier, which is secret, substantial and identified; in this context, 'secret' means that the know-how, considered as a body of knowledge or in the precise configuration and composition of its components, is not generally known or easily accessible; substantial' means that the know-how includes knowledge indispensable to the buyer for the use, sale or resale of the contract goods or services; 'identified' means that the knowhow must be described in a sufficiently comprehensive manner so as to make it possible to verify that it fulfils the criteria of secrecy and substantiality'. Most regulations speak of "know-how” relating to products and processes and the performance of theoretical analyses, systematic studies or experiments, including experimental production, technical checks of products or processes, the construction of the necessary facilities and the obtaining of the relevant intellectual property rights". Know-how (savoir faire) consists therefore of a production and organizational method, often embodied with technological applications as part of an industrialization process, and it consists of practical knowledge of how to do something, e.g. a product. The know-how exploits a wealth of knowledge and constructive artifices acquired through entrepreneurial talent, often by way of craftsmanship and not always formally codified, not in the public domain and therefore such as to originate exclusive information asymmetries, which often encroach on trade secrets, intrinsically characterized by requirements of novelty and not accessibility to third parties. The work leading to know-how, through technical and organizational progress, is typically carried out in teams. Also, in Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3533878 1 the legal field, for the know-how there are significant problems of identifiability, traceability, ascertainability and identifiability (which stem from the immateriality of the res incorporales, inapprensible and evanescent), as well as those of secrecy, substantiality, usefulness and ownership. The know-how, which can be considered an economic asset, and which represents a relational and knowledge heritage, can include tangible and substantial activities such as formulas, instructions and specifications, codified procedures and archetypes, technical devices, production layouts using technology, design, molds or models or intangible activities such as marketing and communication strategies, quality testing techniques, production and organizational procedures and skills. The knowhow refers both to the mass production, in which the organizational and production strategies are serially codified and standardized ("customized"), and to production by order, which represent "tailormade clothes" in which the component craftsmanship and creativity are enhanced. In any case, it is a matter of expertise and confidential internal knowledge linked to a reproducible creativity of technical and/or commercial proprietary information, with an indefinite and potentially infinite useful life, which differentiates the know-how and trade secrets from patented inventions. The extension of the concept, in its fundamental division between technical-industrial and commercial know-how (linked to marketing), is concomitant with the growing importance of innovation as a strategic driver. Insofar as patenting requires some form of disclosure, many inventions remain deliberately confined to the field of industrial secrets, where knowledge, as notorious, must be inaccessible; especially in process inventions, industrial secrecy typically offers greater guarantees, than patenting, against possible violations by third parties. The know-how, through an orchestrated process of apprenticeship (learning by doing), involves process and product innovations, which at the strategic level can be a source of competitive advantage, understood by Michael Porter as cost advantage and / or differentiation, in the context of competition between companies. The voluntary cognitive dissemination of know-how is expressed in the know-how, as a demonstration of certain methods, practices, procedures or processes, including in the context of technical assistance agreements. The know-how can be properly understood as a synergistic glue of the "organized complex of goods" that constitutes the company, to be understood also as a Coasian nexus of contracts, characterized by the ability to create, transfer, assemble, integrate and economically exploit activities deriving (also) from knowledge; its ambiguous perimeter does not always allow a clear demarcation with respect to other intangible assets, represented, first of all, by goodwill (acquired for consideration and therefore accounted for, or, more frequently, internally generated), understood as a residual category of surplus value not otherwise allocable. But the knowhow is also the basis of R&D that can lead to the patenting of original inventions and sometimes can be associated with trademarks, considering their nature as distinctive signs that also expound qualitative characteristics based largely on know-how. And the know-how can also be contiguous to the software or, sometimes, to the rights of use of the intellectual works. The knowhow is, in the broadest sense, also the cognitive monitoring for the quality guarantee and for the repair of the products, with the induced of the after-sales market, noting also for the reduction of defects, with consequent limitation of the product liability. 2. Galilean replicability and industrialization of the experimental scientific method With the invention of the Galilean scientific method, the concept of reproducibility of experiments was introduced, which are the basis of the knowledge acquired through empirical attempts, then systematized, both in scientific theories and - as far as herein is concerned - in a technological Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3533878 2 organizational context of functional and industrialized replicability, in order to make each experiment productive and successful. The scientific method uses an inductive and deductive approach and is aimed at achieving an objective - not arbitrary - knowledge of empirical reality, in a reliable, verifiable, shareable and universally valid way. All this is based on heuristic analysis, i.e. on empirical intuition based on experience, including artisan experience, to be replicated on an industrial basis if necessary. Empirical observations, hypotheses and deductions are used to draw replicable conclusions, through experiments inspired by know-why. Everything is linked to the concepts of industrialization (mass production), replicability, scalability and transferability which, as will be seen below, are of fundamental importance to fill the know-how with practical-application contents and to allow it to be exploited, shared and negotiated. The application of a scientifically replicable method Cartesianly delimits the subjectivity and irrationality of the know-how, favoring its industrialization, even if with the risk of weakening the creative vein, in favor of a replicating technicality. The know-how stems from the experience and the maieutic - Socratic - effort to bring out new industrial ideas, from the custom applied to making, inventing a method, codifying and replicating it, using the technical archetype for mass production and the systematic organization of the business model. All with iterative procedures based on often unsuccessful attempts, with progressive refinement of knowledge and skills. The know-how, understood as an engineered development of the technique, is a two-bladed scissor: deductive because it applies the first principles and inductive using the scientific method. The formation of know-how is usually a slow and gradual process, based on small steps and empirical feedback often unsuccessful, with attempts and errors in constant evolution, which continuously redirect the strategies of incremental enhancement of the company. The incremental training of know-how, even in the context of a process of co-creation of value, can be inspired by reverse engineering processes, which is based on a detailed examination of the operation, design and development of an invention applied by others, in order to produce a similar one, improving its efficiency and quality. Respect for the rights of others, especially in the case of patented inventions, turns out to be essential to avoid litigation. 3. Protection, sharing and transfer of know-how The protection of industrial secrets, even in the absence of patenting, is possible through instruments of protection and safeguarding as an inhibitory and compensatory measure, for example against unfair competition and its inherent abuses. The vulnerability of the know-how is also connected to the technological innovations that allow to record images, forms, processes - all with elements of sophistication once unknown (through photocopies, scans, films, digital photographs, recordings, computer duplications ...) - operating more and more through tools of technological piracy to unlawfully steal of data and sensitive information, with a possibility to store data and transfer them via the web that allows a real-time migration of the wealth of differential knowledge stolen. The damages deriving from the subtraction of know-how are potentially very significant and this imposes the adoption of particular cautions also in the occasion of the more and more frequent moments of sharing of technologies (knowledge sharing), made necessary by increasingly interdependent value chains, in the ambit of which tacit knowledge becomes at least partially explicit. In sharing know-how, strategic decisions to make or buy are marked by increasing specialization, which expands the scope of cooperation with other external parties, including in the context of Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3533878 3 agreements of business networks or technology parks and in an increasingly global perspective. From the immateriality of the know-how comes the characteristic of an unrivalled good, in which the transfer to another subject involves the possibility of use by the assignor, with the consequent creation of a duopoly. The transfer of technology, by way of sharing also through licensing contracts, or with final sales, often occurs in the context of extraordinary operations, now robbed of ordinary because of their frequency, such as transfers, contributions or demergers of companies or their branches, mergers, exchanges, etc. Moreover, the transfer of know-how requires its prior identifiability, at the perimeter level, and often entails the need to associate it with other tangible or intangible assets (machinery, patents, qualified personnel ...), to which it appears synergistically and ontologically connected. Key managers represent a critical aspect of know-how and the transfer of qualified personnel is the indispensable "software" governing the transfer of technologies; it must be accompanied by adequate training of new staff and, once again, the codification of procedures and knowledge, to preserve and depersonalize its use, making them fungible and interchangeable with knowledge management tools. Contracts for the assignment or licensing of know-how may lead to unfair competition, even with criminal relevance, in the event of unlawful disclosure of industrial secrets. The codification of tacit and routine procedures, mainly with advanced Enterprise Resource Planning management software, is an increasingly essential prerequisite for the preservation and transferability of know-how. The storage of sensitive and strategic data is increasingly using outsourcing and back up tools, such as cloud computing, with outsourcing of security that solves some problems, but creates others, also in terms of responsibility. The dissemination of know-how is also based on the know-how of social networks, blogs and chats, which allow exchanges of opinion and, more generally, the sharing of ideas within discussion forums; the libertarian nature of the network also clashes with the entrepreneurial need to segregate knowledge, unlike what happens in academia, where free dissemination is a key principle of the dissemination of scientific thought, also for the purpose of its validation and refutability. The diffusion of the know-how is also stimulated by its frequent horizontal scalability (expanding its use in more companies with similar corporate purpose) and vertical scalability (with synergic crossings of know-how in functionally integrated companies); the extension of the value chain to more synergistically interconnected subjects and the assembly of the surplus value around a shared knowhow, are at the origin of more refined competitive structures, also in a view of an industrial district, which raise the competitive barriers to entry towards potential new competitors, preserving the incumbents' incomes. In this sense, know-how is the source of the competitive advantages, sometimes even prodromal to the achievement of monopolistic rents (which tend to be increasingly ephemeral, as a result of increasing competitive pressure or antitrust provisions). The implementation of a codified system of knowledge is particularly important for large companies that typically repeatedly face the same problems, of which there is often little awareness, and that have a high turnover of staff, resulting in "skills traps". The critical mass of continuous investment in skills is an increasingly essential strategic element, to the benefit of larger companies and/or those capable of doing systemic work. Investments in basic and applied research are made based on market opportunities, the funding that can be obtained, including public funding, and the degree of legal protection with which it can be protected. The networking of know-how is an increasingly valuable driver for the creation of value, especially through the strategic sharing of economies of experience and scale (with a minimization of fixed costs Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3533878 4 shared, first of all at the production level); the case in point is particularly relevant in intangible intensive sectors intrinsically characterized by a high scalability of economic margins (and the consequent financial flows). The preservation of know-how is also based on the preparation of remunerated non-competition agreements, also to limit the brain drain and, more generally, to retain the knowledge acquired within the company perimeter. Technology transfer refers to knowledge, technology, production methods, prototypes, patented inventions or, more rarely, know-how on the part of governments, universities, public and private companies, research bodies, individual inventors. 4. Know-how Transferability Given the fact that trademarks and patents (which are characterized by particular problems of economic evaluation) can be conferred, since they can legally be configured as real assets, since their transfer methods are regulated and they can therefore be acquired instantaneously and definitively by the company's capital, there are those who believe that know-how and unpatented inventions cannot be conferred, because they lack the legal protection in favor of the owner, which the legal system, on the other hand, recognizes to registered intangible assets. Other authors discuss between the need for confidentiality, typical of know-how, and the need to adequately describe the branch by conferring. The risk surrounding the right of ownership of such assets would in fact be transferred to the transferee company, with consequent risks regarding the effectiveness of the capital and potential harm to third party creditors (including those of the transferor company, whose participation in the transferee company could be overvalued). The inventor could transfer the same asset to other parties, both before and after the transfer, with the consequent devaluation of the value transferred. The sharing and, above all, the transfer of know-how, involve the emergence of tax issues, first for income tax purposes, in which the identification of an appropriate tax base, also in relation to the normal value of what is being transferred, plays a central role. Even more delicate are the frequent international intragroup transfers of know-how, which postulate the occurrence of transfer pricing problems, based on a comparison with comparable transactions between independent counterparties. This is clearly a case that many times goes beyond a mission impossible, especially when the specificity and peculiarity of the know-how, which is the distinctive aspect, also in terms of reputation and consequent enhancement, prevent any possible comparison. 5. Economic and financial evaluation The estimate of the market value of the know-how must typically be placed in an evaluation context that considers not only the company or the branch as a whole subject to evaluation, but also - in particular - its intangible resources, starting with those ontologically most contiguous to the knowhow (i.e. patents and, residually, goodwill). The exploitation of know-how also stems from the value chain of which it forms part and from external sources of evaluation, as shown in Figure 1. Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3533878 5 Figure 1. - Links between know-how, value chains and external evaluation sources Accounting principles IAS/IFRS OCSE Guidelines (transfer price) Economic/Financial/Marke t valuations/ transfer/ sharing External transactions intercompany transactions KNOW-HOW license Value chain (income statement) incremental income patents KNOW HOW start up value added exchange value > value in use Gross margin (EBITDA) scalable trademarks other intangibles 5.1. Applicability of empirical and analytical assessment methods With reference to intangible assets not registered or specifically protected, such as know-how, the valuation is subject to high inter-temporal variability, being anchored to provisions aimed at drawing up the "strategic, industrial and financial plans" applicable to the joint-stock companies. Variability is incorporated in the risk to be considered in the estimates and for this purpose the information contained in the report on operations can provide valuable insights. The extreme breadth of the possible evaluation interval is demarcated, in its extremes, by upper and lower limits, in the hypothesis of (full) going concern (full business continuity) or in liquidation break up scenarios, in which traditionally intangible resources lose most of their value, especially if they are not independently negotiable or synergistically connected to other assets; in the hypothesis of discontinuity, the "organized complex of assets" is completely eliminated. The different value gradations also reflect the possibilities for growth and, with them, the possible scenarios to which the estimates can be associated. The choice of methods to be used depends on the type of intangible resource and the purpose and context of the evaluation, but also on the ease with which reliable and meaningful information on the resource and the market in which it is strategically positioned can be found. Of the different methods, the complementarity in identifying - from different angles - the multifaceted aspects of the intangible object of evaluation, suitable to allow an integrated evaluation, must be grasped: for example, the relief from royalties are also in function of the incomes or incremental cash flows that derive from the exploitation of the intangible resource and that interact also with the market surplus value or the multipliers of comparable companies; the incremental patrimony derives from an accumulation in the years of differential income; the costs of reproduction estimate the future benefits and the independent estimate of the average differential goodwill between patrimonial methods and Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3533878 6 incomes. The different methods should in theory lead to similar results, although the relief from royalties and reproduction cost method sometimes tend to provide lower valuations than the differential income method or market comparisons. The applicability to know-how of the different evaluation methods requires an adaptation that takes into account their intrinsic characteristics, if necessary, also in a stand-alone perspective, in which the know-how is considered and is therefore "extractable" from the company and distinctly assessable. The evaluation can be carried out for different purposes, even in litigation, in case of unfair competition with appropriation, replication and/or undue imitation and usurpation of know-how. The value of experimentation - with its practical implications - is also a fundamental element of knowhow. Know-how creates value if it is unconventional, if it is unsettling, the result of an engineered creative rationality that allows a mastering of complexity. In the evaluation, they note considerations of a sectoral and/or commodity nature, which in some areas make it easier to identify know-how. The risk of duplication in the valuation must always be borne in mind, where there is a lack of exclusivity (which in the abstract is not limited by the intangibility of the know-how and its consequent multiple reproducibility and transferability) and a clear segmentation and specificity of loyalty compared to other similar assets, represented above all by goodwill, patents, trademarks and other intangible assets. The evaluation time horizon must take into account the nature of the know-how, which has a potentially indefinite duration, but also forcibly ephemeral and subject to a tendential unpredictability of the life cycle, which depends on the interaction, often capricious, of competitive pressures and external competitive reactions with "entropic" defensive barriers that inhibit appropriateness, based on secrecy, intrinsic complexity and other instruments, including contractual ones, of protection against imitations. The deterioration and erosion of value, in the case of intangibles and know-how in particular, derives from its potential obsolescence and technological successions, which eliminate its exclusive connotations, and not from a physical deterioration related to the use, which indeed increases the value, even in view of economies of experience, as well as visibility and synergistic sharing with other inventions or processes. The strategic value of the know-how must also be appreciated in terms of uniqueness, specificity, non-permeability and exclusivity, which are the basis of killer applications that disorient the market, which must be associated with a flexible versatility, even in terms of applications to multiple sectors, with customized adaptations. A) The relief-from-royalty method An easily applicable empirical method is based on the determination of the "presumed royalties" that the owner of an intangible resource would have required in order to authorize third parties to exploit it (we also speak of the "consent price" method). The relief-from-royalties method is particularly indicated where one wants to arrive at the determination of an exchange value of the immaterial resource. The presumed market value of an intangible resource can be estimated as the discounted sum of the relief royalties (which the company would pay as licensee if the intangible resource were not owned) discounted over a time horizon of at least 3-5 years. The concept of reasonable royalty can also be relevant in the field of litigation in the quantification of patent damages for unlawful use of know-how. In the evaluation of a company with a know-how to be evaluated, the presence of license agreements is particularly appreciated by investors, also because it generates revenues typically not occasional and is a signal to the outside of the technological heritage and innovative capacity of the company. Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3533878 7 B) The incremental income method The value of an intangible resource is the greater the higher the expected economic and operational results that can be associated with it. Therefore, if a going concern is considered, the contribution of an intangible asset in terms of price and/or volume increases (and therefore of economic margin) to the profitability of the business can be measured by the differential income method, which determines the value of the intangible resource to an extent equal to the present value of the sum of the above defined differential income that it is likely to produce in the future. The know-how can therefore be evaluated if and in so far as it gives rise to tangible differential economic benefits and potential future benefits, which are expressed in a premium price, understood as the price differential of the product characterized by know-how. The number of years of discounting the income from the exploitation of the intangible resource depends on its life cycle (useful life). A possible variant is based on the estimate of the incremental gross operating margin or other partial economic margins that the intangible resource makes it possible to obtain, to which a reasonable multiplier derived from negotiations of comparable intangibles is applied. In addition to or as an alternative to the incremental income, the additional cash flow generated by the intangible resource can be considered. The use of the intangible resource acts on the economic margins expressed by the differential between revenues and operating costs as it ideally allows both to increase revenues (with higher direct sales or with royalties receivable from licenses) and to reduce costs, producing with less labor intensive techniques and suitable to allow savings of other costs (production, organizational, energy ...). The stratification of differential incomes thanks to the know-how generates an incremental patrimony, which expresses the differential between market value and book value of the company; it is a suitable element to express - in a rather coarse but often effective way - the surplus value of intangible assets that very rarely find "satisfaction" in their book value and that have led the doctrine to speak of differential "ghost". The lack of or symbolic recognition and capitalization of know-how costs has an impact, on the one hand, on the lack of depreciation and, on the other hand, on the potential undervaluation of shareholders' equity, with a book value lower than the market value. Both the method considered here, and that under A) of the relief from royalties, can be traced, in a broad sense, to the income methods, based on a projection of normalized future income, to be discounted over a predefined (or unlimited) time horizon, consistent with the expected useful life of the know-how, at a reasonable rate, which also incorporates the risk associated with the expected future manifestation of income, in terms of both an, and quantum. C) The estimate of the cost incurred (or of reproduction) In the absence of available data on income capacity, a possible alternative is that of the cost incurred in the past to create the intangible resource and to occupy in the market the positions reached by the same at the valuation date. The identification of a historical cost of production, based on an analytical accounting that allows to functionally separate the costs for the know-how from the others, is preparatory to the estimate of a current cost of reproduction, having the nature of investment and therefore oriented to the expected future benefits and the potential for economic return. However, this procedure is limited in relation to the differential income method. A limit derives from the known unfitness, due to the change in the purchasing power of the currency and the change in economic conditions, of the historical costs to measure values later. The second limit is since the value of an asset is not only due to the costs necessary to obtain it, but also and mainly to the future benefits that can be derived from it. A step forward with respect to the previous method is the process of reproducing an immaterial resource that is functionally equivalent, which replaces the historical costs with the costs of Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3533878 8 reproducing the asset ex novo, i.e. the costs that would have to be incurred at the time of valuation to reconstruct the same value that the immaterial resource reached at that time. However, in the procedure now examined, there is still the limit of not considering the profitability of the investment and also the opportunity cost deriving from the immediate non-use of the intangible resource. The existence of high and uncertain fixed costs related to the reconstruction of know-how, represents a barrier to entry that segregates the market and distances competitors. D) The complex capital method The equity methods traditionally used in continental Europe are based on an analytical valuation of individual assets and liabilities, with a comparison with their book value, in order to adjust the book value of equity to arrive at a market value of equity. In this method, in the so-called "second-degree complex" variant, there are also peculiar hotel activities, such as know-how, which are not normally accounted for and do not typically have an independent market value. The capital gain should then be expressed net of potential tax liabilities, taking into account a tax profile that will only be applied when there is a need to move from an abstractly estimated value to a value-added price, monetarily negotiated. E) The mixed capital-income method, with independent estimate of goodwill. The main method for estimating goodwill, at least according to the doctrine and practice of continental Europe, is based on the comparison between the extra-yield that the company is able to generate for a limited period (or, more rarely, unlimited) and the normal return on capital of comparable companies, within the product sector of reference. To the extent that the goodwill is attributable to the know-how, the method can be used to estimate this intangible resource; a critical point derives from the not always easy separability of the knowhow with respect to other intangible resources, which in the goodwill find, in a residual way, their natural fund of values. The extra income due to know-how is comparable to differential income and therefore the two methods can find useful elements of convergence or, at least, complementarity. 6. Product and process innovation Innovation is one of the key elements of a company's differentiation strategies, which allow it to become unique, acquiring a competitive advantage that can result in monopoly rents. The innovations can be product and/or process and are divided into main or derived: the former have an absolute degree of creativity and originality compared to the previous knowledge, while the latter have a relative character and may consist in a progress or improvement of techniques; the derived inventions may be of improvement (resolution in different and more convenient forms of technical problems previously solved in another way), of translation (transposition of a known principle or of a previous invention in a different sector and with a different final result) or of combination (ingenious and original coordination of elements and means already known with a technically new and economically useful result). In addition, "chain-linked" inventions, which result in dependent patents or patent families along the same supply chain, are of particularly important. There may be cases of dependent and derived inventions, of selection, improvement, combination, translation, whereby the original patent takes on greater value as a result of other patents or inventions that depend on it, giving rise to significant synergies. Differentiation helps to create barriers to entry into the market in which the company operates, limiting competition and the substitutability or comparability of the company's assets; this can allow it to achieve and maintain high economic margins, even in the presence of an external demand that Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3533878 9 struggles to find satisfaction elsewhere and that may suffer the temporary monopolistic force of the company holding the patent and can afford the luxury of activating price-maker strategies (with a clientele specularly price-taker). At a strategic level, the differential nature of inventions, which contribute to making the company "unique", sheltering it from comparison and allowing it not to undertake the onerous path of cost differentiation, is associated with their scalability, which allows its use - through industry and reproducibility in series - where costs are marginally decreasing as volumes increase. Low marginal costs and economies of scale are positive aspects of patents, which are also the result of often very costly initial investments and uncertain outcomes. The wealth (portfolio) of differential knowledge - and, as such, unique and innovative - is at the basis of the evaluation not only of the existing intellectual property, but also of the inventive propensity, fundamental to preserve and increase the strategic value, especially in companies that operate in developed countries and that can hardly leverage on cost differentiation, also because of the high incidence of labor costs. 7. Know-how and creditworthiness The presence of know-how within the company tends to have a limited direct impact on the creditworthiness of the company to be entrusted, considering first of all the limited recoverable value of the know-how and it’s not always easy identifiability, measurability and separability with respect to other assets that make up the "organized complex of assets" that defines the company. This is particularly true in crisis situations, where business may not be guaranteed, and the company is destined to progressively lose its synergistic value. The residual value of the know-how changes according to its destination to minimize the effects of a crisis: if it is transferred with other healthy branches or associated with intangibles with independent collateral value (such as, for example, certain patents, or the human capital expressed by employees and collaborators subject to enucleation by the bad company) then there will evidently be a more limited loss of value. The know-how does not typically enter into the calculation of the rating and transfers to the processes responsible for the evaluation of the creditworthiness its well-known criticalities, first of all in terms of failure to account, resulting from the prohibition to record the internally generated goodwill (of which the know-how is a close, tending in many cases to converge in the bed of the definition of goodwill itself) and the growing distrust towards the capitalization of costs, which tends to be not allowed by international accounting standards. That said, it should be noted that the know-how, especially in situations of going concern, retains a fundamental role in allowing and facilitating the proper functioning of the company, on which depend the economic and income flows and the stratification of assets, the basis of the ability of the company to repay debts and to preserve the creditworthiness. Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3533878 10 REFERENCES CASSIMAN, B., PÉREZ CASTRILLO, D., VEUGELERS, R., (2000), Endogenizing Know-How Flows through the Nature of R&D Investments, August, UPF Working Paper No. 512., http://ssrn.com/abstract=248683. CHOI, J.P., (2001),Technology transfer with moral hazard, International Journal of Industrial Organization, 19 (1-2), pp. 249-266 LEE D., VAN DEN STEIN E., (2006), Managing Know-How. HBS Technology & Operations Management, Unit Research Paper No. 07-039, December. MENDI, P., MONER-COLONQUES, R., SEMPERE-MONERRIS, J.J., (2016), Optimal know-how transfers in licensing contracts, Journal of Economics/ Zeitschrift fur Nationalokonomie, Volume 118, Issue 2, 1 June 2016, Pages 121-139. MORO VISCONTI, R., (2013), Evaluating Know-How for Transfer Price Benchmarking, in “Journal of Finance and Accounting”, 1, 1. POSTON, T., (2015), Know How to Transmit Knowledge?, in “Noûs”, Volume 50, Issue 4, December, Pages 865-878 ROBERTS, J., (2000), From know-how to show-how? Questioning the role of information and communication technologies in Knowledge Transfer, in “Technology Analysis & Strategic Management”, December. 11 TEECE, D.J., (2008a) The Transfer and Licensing of Know-How and Intellectual Property: Understanding the Multinational Enterprise in the Modern World, World Scientific Publishing, Singapore. TEECE, D.J., (2008b), Technological Know-How, Organizational Capabilities, and Strategic Management: Business Strategy and Enterprise Development in Competitive Environments, World Scientific Publishing, Singapore. VISHWASRAO, S., (2007), Royalties vs. fees: How do firms pay for foreign technology?, International Journal of Industrial Organization, 25 (4), pp. 741-759 Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3533878