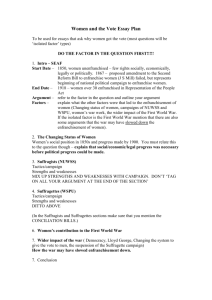

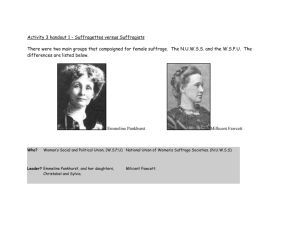

The Suffragettes : Divisive Troublemakers or Unsung Heroines? By the turn of the twentieth century, the issue of enfranchisement of women was nothing new. Under the leadership of individuals such as Lydia Becker and Milicent Fawcett the National Society for Women’s Suffrage or National Union of Women’s Social Societies all the way from 1897 had painstakingly built up support among members of parliament by respectable constitutional means. Yet these organisations had failed to push the issue into the forefront of the British political agenda. This changed dramatically with the emergence of Emmeline Pankhurts’ Women’s Social Political Union (WSPU) in 1903. This organisation, disillusioned with constitutionalism, would force the issue into the lives of every woman in Britain - mainly through usage of antidemocratic methods. Certainly, the adoption of mass protests, heckling, petty violence, shock tactics and deliberate media attention seeking helped promote the cause of women’s suffrage. From the WSPU emerged leaders, such as Christabel Pankhurst and Annie Kenney who would come to represent the modern, crusading woman, and thus inspire ordinary women around the country to further the cause by joining. The methods of the suffragettes were new and innovative, sensationalising the cause and attracting thousands to its rallies and protests. Yet, the true success of this movement can only be fully established by looking at governmental response. By the start of the Great War, the suffragette movement had died down, indeed many of its leaders underwent a transformation from dissident to patriot. By the time of the first enfranchisement of women, in 1918, the suffragettes were not on the political scene at all, even less so by 1928. Therefore, their role in the actual passage of laws giving women the vote is debatable. Their major success appears to have been in drumming up popular support for the cause through a variety of methods, thus making it eventually unavoidable for the Government to address women’s suffrage. Indeed, the adoption of militant anti-democratic tactics came some way from a realisation that passive constitutional methods seemed totally ineffective. The campaigns of the militant suffragettes before 1914 are so well known that we tend to regard them as an inevitable element, perhaps the only significant element, in the struggle for the enfranchisement of women. However, this is not entirely the case. Constitutional campaigners for women’s suffrage has won the argument for giving women the vote by converting a majority of MP’s, even before 1900. As a result, the 1897 House of Commons began to vote in favour of bills introduced by backbenchers to give women the vote - this represented a massive achievement for the women’s cause which has traditionally been overlooked amid the notoriety attracted by the anti-democratic suffragette campaign after 1905. This appears to cast new light on whether such militant tactics were altogether necessary and effective. However, importantly, that the politicians sympathy has been aroused did not mean they regarded enfranchisement as a matter of urgency. The Pankhurts’ organisation did not introduce any radical new ideas into the issue of attaining the vote for women, their contribution was to force the issue upon politicians by devising fresh tactics and attracting significant amounts of income into their campaigns. This independence however came only as a result of the organisations split with the Labour Party. Emmeline originally believed the new Labour Party would be the instrument of enfranchisement for women. Yet at the 1902 Conference a significant resolution passed promoting adult suffrage, rather than female suffrage as a priority. Labour men such as Philip Snowden and Glasier believed that a limited franchise to women would disadvantage the Party indeed, Glasier suspected the Pankhurts’ motives, “they want to be ladies, not workers.” To the new and vulnerable Labour Party, fully endorsing a women’s suffrage movement represented a risky divergence, one which they could do without. Therefore a gulf emerged between constitutionalist suffragists and those willing to experiment with new shock tactics, in order to speed up the process of enfranchisement for women. Christabel’s misgivings centred around Eva Gore-Booth and Esther Roper, ardent constitutional suffragists who believed in a close alliance with Labour. Christabel remarked, “why are we expected to have such confidence in the men of the Labour Party?” Teresa Billington, another woman attracted to the independence offered by the WSPU commented that not one of the Labour Party’s advocates “were interested in winning women’s suffrage.” Therefore, it was this disillusionment that lay at the foundation of the WSPU. The explanation for the subsequent adoption of militant tactics lies to a large extent with the Pankhursts’ frustration with the Labour Party. These women were already reacting against the constitutional forces for women’s suffrage, and had seen how little it had achieved. However, for years the WSPU ran without any formal organisation, its only real assets were the energy and enthusiasm of the Pankhurts. During 1903-04 the methods used by the WSPU continued to be constitutional and thus not essentially different to the other established suffragists. The fact that no formal plan of action had been devised goes some way towards proving the opportunist nature of the whole organisation. Experimentation with anti-democratic methods first appeared in 1904, when Christabel interrupted Churchill in Manchester’s Free Trade Hall. 1905 proved to be the key year when the WSPU leapt into national prominence and veered sharply away from constitutional methods to the militant tactics for which they were to become famous. This last point is worth highlighting, for it was the militant tactics adopted by the WSPU which catapulted them into national significance, in effect they created the image of the romantic struggle for women’s enfranchisement. The political climate helped Christabel and Emmeline exacerbate their new tactics. The credibility of Balfour’s government had dwindled and expectations of an early general election and Liberal victory escalated. Thus excitement was created surrounding local and national politics and aided the WSPU in their push for recognition. Significantly, by 1905 its membership did not even exceed thirty, therefore it had to make its presence felt beyond its numbers. Emmeline concluded that attempts to gain the vote via back-benchers votes were futile, she twisted thinking towards more direct action that would force the government to make note of the demands of the people. Indeed, the Balfour government had found time to introduce bills dealing with levels of unemployment and the Scottish Churches all because it considered these topics urgent - therefore it was the WSPU’s epiphany to make the issue of suffrage urgent and unavoidable. This accounts for crucial importance in assessing the extent to which the suffragettes militant tactics accounted for the eventual passage of bills enfranchising women in 1918 and 1928. Christabel wrote in 1905 that the WSPU “was making no headway, our work was not counting.” This emphasises a recognition that mere political passivity would not be enough to force the issue of women’s suffrage. Thus a new wave of interventions were organised, most notable in the Free Trade Hall once again, where banners exclaiming “Votes for Women!” were unfurled. It became apparent that these episodes succeeded in creating a new momentum for the WSPU by adding a human, desperate struggle twist to women’s suffrage. Annie Kenney’s release from prison following the episode was celebrated by a crowd of 2,000 - indicative of the furore the WSPU had managed to build up. By provoking the authorities into creating martyrs of its members, the WSPU was having a bigger impact than any women’s society had ever had. “Twenty years of peaceful propaganda had not produced such an effect” wrote Hannah Mitchell, another of the new militant breed to join with the Pankhursts. Furthermore, The Times in London (which had erstwhile chosen to ignore the women’s cause) covered the events in Manchester. Examples such as this confirm the public success of the suffragette movement - they succeeded in driving the issue of women’s votes into the public domain of ordinary citizens as well as politicians. Additionally, heightened attempts to bait politicians at home and on the platform attracted considerable sympathy, a telling remark concerning the nature of British government comes from the Daily Mirror, “Parliament has never granted any important reform without being bullied.” This quote goes some way towards justifying the anti-democratic measures employed by the suffragettes - that, in some way, making a fuss over the issue would bring it to light in Parliament. The spreading of the movement to London must also be considered highly significant - with this geographical shift from the North came a new social demographic member, many of the suffragettes were now respectable middle-class ladies - which brought not only vital financial income into the organisation but also home the argument that enfranchisement was wanted by all classes of female. However, this all-out militancy had severe drawbacks, it led to a sense of dictatorial reign by Christabel, leaving no room whatsoever for any sentiments of constitutionalism. It was a full fronted attack upon the system which had chosen not to include them, which sometimes meant the organisation actually attacked its own supporters and politicians sympathetic to the cause such as Lloyd George. Over time this weakened the WSPU and the militant doctrine alienated some of the organisations more well off members. Yet these respectable elements within the organisation had to be catered for, such influx of finance enabled the Union to develop a machine capable of taking on the major political parties. In order to sustain such a high level of organisation, it became necessary to ensure the WSPU was constantly in the public eye. The Pankhursts felt obliged to employ new and more radical forms of militancy in order to retain the impact of their campaign. In arranging more and more deputations and protests, the WSPU was causing a huge political ripple. The response of the authorities played into the hands of the suffragettes, for example in February 1907 after the Women’s Parliament, protestors were confronted by mounted police - such heavy-handedness enabled the women to gain the moral high-ground in their struggle. However, with the succession of Asquith as Prime Minister, the suffragettes prospects deteriorated sharply. This single individual, it can be claimed, held back the tide of the militant campaign perhaps a less obstinate Prime Minister would have enacted enfranchisement sooner, but that would be to speculate. What can be asserted however is that Asquith’s intransigence directly forced the suffragettes to pursue increasingly radical techniques - therefore the best way to respond to Asquith was to offer unmistakable proof that he was wrong in assuming women’s suffrage still lacked public support. This was evidently shown in May 1908 when a crowd of 30,000 converged on Hyde Park. Asquith’s refusal to accept the vociferous demands of this peaceful protest led Christabel to interpret this as proof that he was deaf to purely peaceful pressure - Union leaders therefore agreed extended militancy was a necessity. Yet Asquith’s strength of character underpins the period up-to Lloyd George’s coalition Government in 1916. Even when faced with public disorder and violence, Asquith remained unshakable in his opposition to the women’s suffrage movement. By 1910 the issue was resolved to a clash between the suffragette campaign and Asquith’s nonmoving. Even the introduction of the hunger strike in July 1910 made no change from the government’s position. Christabel felt the hunger strike “has given us new means of entirely baffling the government.” Yet it did not even Asquith’s condoning of forcible feeding did not enrage public opinion enough to foster a change in the law. Non-conformist Reverend Campbell wrote, “there is something extremely repugnant…in the knowledge that women are being subjected to such violent indignities.” Furthermore, the crisis over the House of Lords in December had distracted attention away from the suffragettes. The suffragettes had certainly caught the nation’s attention, never more so than after Emily Davison’s suicide at Epsom races in June 1913. Her actions indicated just how far the women were willing to go, and yet the fact that it would take another 5 years for some women to become enfranchised speaks volumes for the overall effect it had. The suffragette movement succeeded in sensationalising the votes for women campaign, it did not succeed in bringing about immediate parliamentary change for the inclusion of women into the franchise. The outbreak of war more or less finished off any momentum the movement had left by 1914. The cessation of the militant campaign involved an admission that militancy had been no more successful in winning the vote than constitutionalism. Emmeline and Christabel, the face of the WSPU, became allies of the establishment, whilst Sylvia and Adela moved further to the Left. The suffragettes had forced the Commons to regard votes for women as a serious matter, this fact cannot be disputed. But war carried such rapid social and political change that by 1917 the issue of women’s enfranchisement appeared in a fundamentally different context to that of the pre-war years. As men left jobs to fight, they were replaced by women. Women were thus doing kinds of jobs that they simply had not done before, for example by April 1918 701,000 women were employed in munitions. The War Office commented in 1916 that women “had showed themselves capable of replacing the stronger sex in practically every calling.” The praise given to women on the home front marked a change in male attitudes towards female enfranchisement. Instead of burning letter-boxes and throwing stones, they were driving the economy of wartime Britain. When the Coalition government took power in 1916 Balfour, Bonar Law, Lord Cecil and Selborne became Cabinet Ministers - all pro-suffragists, with Lloyd George becoming Prime Minister, female enfranchisement’s old foe had at last been removed. Remarkably, Asquith in 1917 noted to the Commons, “How could we have carried on the war without them?” Significantly, the war had changed his most stubborn of minds, not eight years of suffragette agitation. Lloyd George remarked, “the war had had an enormous effect upon public opinion…women’s work in the war has been a vital contribution to our success.” It is possible to argue the war had a more significant impact upon the enfranchisement of women than the suffragette campaign before it. One must recognise that there were more obstacles in the way of the suffragettes, most notably Asquith, in order to make a fair judgement. By the time of the second enfranchisement bill in 1928, Christabel had become a rejuvenated Christian, remarking in 1925, “it would be undesirable to re-open the franchise agitation”. Emmeline’s late involvement with the Tory party undoubtedly accelerated the promise made my Baldwin - and in April 1927 another 5.5 million female voters were added to the franchise. However, there had been no anti-democratic methods used to press for a further extension of the franchise, it had come as a natural progression of government policy. The WSPU neglected to develop a broader feminist agenda on which to campaign after the vote had been won - this helps to explain why the suffragettes failed to survive World War I and neither Emmeline or Christabel Pankhurst saw their future in the women’s movement after 1918. The suffragettes, along with their innovative anti-democratic methods, will always be regarded as the vanguard of the woman’s right to vote. In 1936, Christabel was honoured with a DBE and six years earlier her mother’s statue was unveiled along with a plaque honouring over 1,000 women who endured imprisonment for the suffragette cause. Therefore there is some sort of popular legacy left behind the women and their methods. However, in the context of the Bills in 1918 and 1928, their anti-democratic methods had long since ceased - it was Britain’s involvement in the Great War which ushered in a new social phase for all British citizens, including the right of women to vote. Yet the plaque and mere name of the Suffragettes will always have great resonance in the formation of the popular conception that women should have the right to vote. Bibliography Andrew Rosen : Rise up Women Susan Kingsley Kent : Making Peace : The Reconstruction of Gender in interwar Britain Martin Pugh : The Pankhursts Martin Pugh : Women and the Women’s Movement in Britain 1914-1999 Jane Marcus : Suffrage and the Pankhursts Christabel Pankhurst : Unshackled : The Story of How we won the Vote Posted by Harry Mackridge at 05:22