Zarit Burden Interview Short Forms: Validity in Advanced Conditions

advertisement

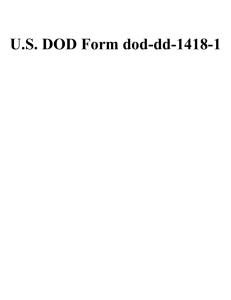

Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 63 (2010) 535e542 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Short-form Zarit Caregiver Burden Interviews were valid in advanced conditions Irene J. Higginsona,*, Wei Gaoa, Diana Jacksona, Joanna Murrayb, Richard Hardinga a King’s College London, Department of Palliative Care, Policy and Rehabilitation, School of Medicine at Guy’s, King’s College and St Thomas’ Hospitals, London, United Kingdom b King’s College London, Health Service and Population Research Department, Institute of Psychiatry, David Goldberg Centre, London, United Kingdom Accepted 3 June 2009 Abstract Objectives: To assess six short-form versions of Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI-12, ZBI-8, ZBI-7, ZBI-6, ZBI-4, and ZBI-1) among three caregiving populations. Study Design and Setting: Secondary analysis of carers’ surveys in advanced cancer (n 5 105), dementia (n 5 131), and acquired brain injury (n 5 215). All completed demographic information and the ZBI-22 were used. Validity was assessed by Spearman correlations and internal consistency using Cronbach’s alpha. Overall discrimination ability was evaluated using the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC). Results: All short-form versions, except the ZBI-1 in advanced cancer (rho 5 0.63), displayed good correlations (rho 5 0.74e0.97) with the ZBI-22. Cronbach’s alphas suggested high internal consistency (range: 0.69e0.89) even for the ZBI-4. Discriminative ability was good for all short forms (AUC range: 0.90e0.99); the best AUC was for ZBI-12 (0.99; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.98e0.99) and the second best for ZBI-7 (0.98; 95% CI: 0.96e0.98) and ZBI-6 (0.98; 95% CI: 0.97e0.99). Conclusions: All six short-form ZBI have very good validity, internal consistency, and discriminative ability. ZBI-12 is endorsed as the best short-form version; ZBI-7 and ZBI-6 show almost equal properties and are suitable when a fewer-question version is needed. ZBI-4 and ZBI-1 are suitable for screening, but ZBI-1 may be less valid in cancer. Ó 2010 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. Keywords: Carer; Outcome; Palliative; Burden; Aging; Validity 1. Background Informal carers are the primary resource for patient care and are known to have high needs for support and psychological morbidity [1e4]. Although there are many suggested interventions seeking to improve their overall well-being, there is little evaluative research into the efficacy of such interventions [5,6]. Measurement of appropriate carer outcomes is essential for such studies. Although there are many measures to assess caregiver burden, strain, well-being, or other outcomes in specific disease, such as stroke or mental illness [7,8], there are fewer measures targeted for the carers of patients with advanced disease. Mularski et al. in a major systematic review of measures Competing interests: None. * Corresponding author. Department of Palliative Care, Policy and Rehabilitation, School of Medicine at Guy’s, King’s College and St Thomas’ Hospitals, King’s College London, Weston Education Centre, 3rd Floor, Cutcombe Road, Denmark Hill, London SE5 9RJ, United Kingdom. Tel.: þ44-0-20-7848-5516; fax: þ44-0-20-7848-5517. E-mail address: irene.higginson@kcl.ac.uk (I.J. Higginson). 0895-4356/10/$ e see front matter Ó 2010 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.014 for use toward the end of life for the National Institute of Health (USA) highlighted ‘‘significant gaps’’ in measuring caregiver outcomes, identifying only two measures in their literature search of 24,423 citations [9]. Caregiver burden is closely aligned to the goals of many interventions and is associated with negative health outcomes in carers of people with common conditions, such as dementia, stroke, and cancer [8,10,11]. Moreover, perceived burden had been shown to predict anxiety and depression in carers of patients with these conditions [12e14]. Caregiver burden had been defined as a contextspecific negative affective outcome, occurring as a result of perceived inability to contend with role demands [15]. There is general agreement that caregiver burden is a multidimensional concept affected by objective elements related to the nature and time of the practical tasks undertaken by carers and subjective elements arising from the perceived emotional, social, and relationship stresses that can accompany this role [8,16]. Therefore, it would seem appropriate to measure caregiver burden as an outcome in advanced disease. 536 I.J. Higginson et al. / Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 63 (2010) 535e542 2. Data and methods What is new? Key findings The 12-item Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI-12) was suitable in all situations; the ZBI-7 and the ZBI-6 were almost equally good and may be suitable for palliative care settings; the ZBI-4 and ZBI-1 were useful when a very short screening instrument was needed. What was known? The ZBI-22 is a widely used outcome measure of caregiver burden and has been validated in diverse caregiving samples. Several short-form versions of ZBI have been developed, but little is known about how well they perform in diverse populations. What does this study add? For the first time, six short-form versions of ZBI have been comprehensively and systematically evaluated in diverse populations. Evidence-based recommendations have been provided for choosing the best shortform version in various settings. The ZBI-6, a further improvement to the ZBI-7, has been developed for palliative care settings. What is the implication and what should change now? Stop using the ZBI-8; use ZBI-6 in palliative care; consider using the ZBI-1 when rapid screening is needed. Although there are other measures, the 22-item Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI) is the most widely used tool for measuring the level of subjective burden among carers [17,18]. Several shorter versions of the ZBI have been developed, including Bedard et al.’s 12-, 8-, 7-, and 4-item screening versions [19e21]. However, the factorial structures of ZBI were established among the carers of patients with dementia whose concerns may be different from carers of patients with cancer or sudden onset illness. Analysis of four abridged versions of the ZBI in 503 carers of people with dementia suggested that the 12-item version was optimal [15]. However, in some clinical settings, such as intensive care units, palliative care, and care of older people, the 12-item ZBI can still be a heavy assessment burden. There is a need to test shorter forms of the ZBI with the carers of people with advanced or progressive illness. Therefore, we designed this study to investigate the validity and internal consistency of six shorter forms of ZBI (ZBI-12, ZBI-8, ZBI-7, ZBI-6, ZBI-4, and ZBI-1) among informal carers of patients with three different conditions compared with the 22-item version as the gold standard. 2.1. Design and data sources This is a secondary analysis using data pooled from four studies. 1. Baseline data from a multicenter evaluation of palliative day care for cancer patients involving six centers across the south of England [22,23]; 2. Baseline data from a two-center evaluation of the ‘‘90 Minute Group,’’ a supportive intervention for the carers of cancer palliative care patients [6]; 3. A national postal questionnaire survey of caregiver experiences of acquired brain injury (ABI) [24]; and 4. Baseline data from a prospective longitudinal cohort study of caregiver burden in dementia involving participants from South East London [25]. All studies collected data from informal carers using the self-reported 22-item ZBI (ZBI-22), with interviewers present in the cancer and dementia studies to provide support to respondents during data collection if needed. In addition to ZBI, the data set contains basic demographic data, including age, sex, and relationship, and clinical data regarding the patients. 2.2. Short-form versions of the Zarit Burden Interview Several short-form versions have been developed. The three most common short-form versions of ZBI are the 12-item version (ZBI-12) by Bedard et al. [19], the eightitem version (ZBI-8) by Arai et al. [21], and the four-item version (ZBI-4) by Bedard et al. [19]. The ZBI-12 and the ZBI-4 were reported in the same study [19]. The ZBI-22 data were factor analyzed using a principal component analysis and revealed a two-factor structure. The items for the ZBI-12 were selected through a combination of high factor loading and high itemetotal correlations across all six situations, and the ZBI-4 screening items were selected based on the itemetotal correlations while keeping the three-to-one item ratio between factors 1 and 2 [19]. The ZBI-8 items were chosen in terms of their factor loadings (>0.65) on a two-factor structure [21]. A new seven-item version (ZBI-7) proposed specifically for palliative care was included for evaluation; the items extracted were decided by an expert committee [20]. However, ZBI-7 included item 22 of the full scale, a global question to assess overall subjective burden. This is unusual, because short-form versions do not usually contain the global question, especially for the measures of subjective burden [8,16,26]. Therefore, we derived a six-item version of ZBI (ZBI-6), excluding this global question. We also tested item 22 on its own (ZBI-1) to understand whether the single global question (‘‘Overall how burdened do you feel’’) would be useful as a screening tool. Items included in each of the short-item versions are listed in Table 1. The responses to every item are in 5-point Likert scale I.J. Higginson et al. / Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 63 (2010) 535e542 537 Table 1 Items included in the short-form ZBI Item Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q5 Q6 Q7 Q8 Q9 Q10 Q11 Q12 Q13 Q14 Q15 Q16 Q17 Q18 Q19 Q20 Q21 Q22 Question (do you feel/wish.) Your relative asks for more help than he/she needs? You don’t have enough time for yourself? Stressed between caring and meeting other responsibilities? Embarrassed over behaviors? Angry when around your relative? Your relative affects your relationship with others in a negative way? Afraid of what the future holds for relative? Your relative is dependent on you? Strained when are around your relative? Your health has suffered because of your involvement with your relative? You don’t have as much privacy as you would like, because of your relative? Your social life has suffered because you are caring for your relative? Uncomfortable about having friends over because of your relative? Your relative seems to expect you to take care of him/her, as if you were the only one he/she could depend on? You don’t have enough money to care for your relative, in addition to the rest of your expenses? You will be unable to take care of your relative much longer? You have lost control of your life since your relative’s illness? You could just leave the care of your relative to someone else? Uncertain about what to do about relative? You should be doing more for your relative? You could do a better job in caring for your relative? Overall, how burdened do you feel in caring for your relative? Gort et al.’s ZBI-7 [20] Higginson et al.’s ZBI-6 (this paper) Bedard et al.’s ZBI-4 [19] Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Bedard et al.’s ZBI-12 [19] Arai et al.’s ZBI-8 [21] Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Higginson et al.’s ZBI-1 (this paper) Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Possible responses to Q1eQ21: 0, never; 1, rarely; 2, sometimes; 3, quite frequently; 4, nearly always. Possible responses to Q22: 0, not at all; 1, a little; 2, moderately; 3, quite a bit; 4, extremely. Abbreviations: ZBI, Zarit Burden Interview; Y, yes. Y 538 I.J. Higginson et al. / Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 63 (2010) 535e542 from 0 (never) to 4 (nearly always). The overall burden is assessed by the total score of all items, with a higher score representing a greater caregiver burden. 2.3. Data analysis Demographic characteristics were described, and differences between diagnostic groups were compared using oneway ANOVA (for age) and chi-square test (for sex and relationship to patient). Total scores of ZBI-22, ZBI-12, ZBI-8, ZBI-7, ZBI-6, ZBI-4, and ZBI-1 were summarized using descriptive statistics. The score differences between three diagnoses were examined for overall differences using KruskaleWallis test followed by Wilcoxon two-sample test if the overall difference was significant. The Bonferroni procedure was used to adjust raw P values (multiplying 3) to control the type 1 error in multiple testing [27]. We planned to examine the subscales of ZBI, but found inconsistencies in the literature regarding the content of the subscales. For example, the original article by Whitlatch et al. [28] presented two subscales: role and personal strain with six and 12 items, respectively. Hebert et al. [29] used these in their factor analysis producing a 12-item version. However, Knight et al. [30], Bedard et al. [19], and O’Rourke et al. [31], when conducting exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis, revealed that different items were included in the role and personal subscales, even though they gave them the same names. Because of the inconsistencies, we did not proceed with the subscale analysis. Validity was assessed by testing for correlations of the ZBI-12, ZBI-8, ZBI-7, ZBI-6, ZBI-4, and ZBI-1 with the ZBI-22 (as the gold standard) using Spearman rank order correlation. Terwee et al. [32] suggest that correlations of 0.7 or more are required. Internal consistency was examined with Cronbach’s alpha, and a value in the range of 0.7e0.9 is good [32]. An alpha value of greater than 0.9 suggests redundant items. For small scales (e.g., four items), values of 0.6 are good, because alpha tends to underestimate internal consistency when the number of items is small [32,33]. Using a total burden score of 21 on the ZBI-22 as the cutoff point for high burden [18], the discriminatory performance of various short-form versions of ZBI was assessed and compared with the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve [34], which was constructed by plotting sensitivity against 1 specificity. Each point in the ROC plot represents a sensitivity/1 specificity pair corresponding to a particular cutoff value. A test with perfect discrimination has an ROC plot that passes through the upper-left corner (100% sensitivity and 100% specificity). Therefore, the closer a ROC plot is to the upper-left corner, the higher the overall accuracy of the test. The point closest to (0, 1) on the curve was used to determine the most optimal combination of sensitivity and specificity [34]. The areas under the curves (AUC) were calculated using the trapezoidal method [34,35]. The AUC represents the overall discriminative ability of a test, that is, the ability to correctly classify those with and without burden. The range of the AUC is 0.5e1.0. A discriminative test is considered perfect if AUC 5 1.0, good if AUC 5 0.8e1.0, moderate if AUC 5 0.6e0.8, and poor if AUC 5 0.5e0.6; an area of 0.5 reflects a random rating model [35]. 95% Confidence intervals of AUCs were computed. A P value below 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. All analyses were carried out using SAS 9.1 package (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). 3. Results One hundred and five, 131, and 215 informal carers for patients with advanced cancer, dementia, and ABI respectively, were recruited, making a total sample of 451. Most carers were womend81% for ABI, 72% for cancer, and 72% for dementia (c2df52 5 5.50, P 5 0.06). The carers of ABI patients were the youngestdmean age (standard deviation) of 54 (11) compared with 66 (12) for cancer and 62 (13) for dementia (F(2,448) 5 42.8, P ! 0.0001). Spouse/partner carers were the most commond59% for ABI, 82% for cancer, 37% for dementiadfollowed by parent (37% for ABI, 4% for cancer, and 0% for dementia) or son/daughter (44% for dementia, 11% for cancer, and 0% for ABI) (c26 5 227.6, P ! 0.0001). Table 2 shows the descriptive statistics of the total score for various short-form versions of ZBI in each diagnostic group. All scores showed highly significant overall difference across three groups (all P values ! 0.001). In all groups, there was a wide range of burden scores. The disease-specific burden pattern reflected in the full-scale ZBI was well captured by all short-form versions. Subjective caregiver burden were lowest for the carers of cancer patients and highest for those of patients with ABI. However, the significance of the difference shown in ZBI-22 (ABI vs. cancer: z 5 7.66, Padj ! 0.0001; ABI vs. dementia: z 5 5.62, Padj ! 0.0001; cancer vs. dementia: z 5 2.03, Padj 5 0.12) was only satisfactorily revealed by ZBI-12, ZBI-6, and ZBI-4. ZBI-1 was among the worst in all the short-form versions for misjudging two pairwise comparisons of ABI vs. dementia (z 5 2.15, Padj 5 0.10) and cancer vs. dementia (z 5 4.30, P ! 0.0001), whereas ZBI-7 (z 5 2.76, Padj 5 0.018) and ZBI-8 (z 5 4.24, P ! 0.0001) did not reflect the difference in comparing cancer with dementia, as was the case in ZBI-22. High correlation coefficients were found between the full version and short forms (Table 3), with correlations well above our criteria (O0.7) for the full scale (range: 0.88e0.97) using all short-form versions except for the ZBI-1. Even with the one-item version (ZBI-1), satisfactory correlation with ZBI-22 was obtained in dementia (rho 5 0.74) and ABI (rho 5 0.78) groups. The full ZBI showed a high Cronbach’s alpha in all three diagnostic groups, ranging from 0.88 to 0.93. The alpha values met our internal consistency criteria of good for all the shortform versions, ranging from 0.69 (for a four-item scale in cancer) to 0.90. Correlations and internal consistencies I.J. Higginson et al. / Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 63 (2010) 535e542 539 Table 2 Descriptive statistics of scores for six short-form and full-scale versions of the ZBI Diagnosis a Version Statistics Cancer Dementia ABI Multiple comparisonsb ZBI-12 Mean (SD)** 95% CI Median (min, max) 12.0 (8.5) 10.4e13.7 10 (0, 36) 15.1 (10.0) 13.4e16.8 15 (0, 43) 21.7 (10.1) 20.4e23.1 22 (0, 46) B**, C** ZBI-8 Mean (SD)** 95% CI Median (min, max) 5.5 (4.7) 4.6e6.4 4 (0, 24) 8.8 (6.1) 7.7e9.8 9 (0, 28) 11.5 (7.2) 10.5e12.4 11 (0, 31) A**, B**, C** ZBI-7 Mean (SD)** 95% CI Median (min, max) 7.4 (5.6) 6.3e8.5 7 (0, 21) 9.9 (6.8) 8.7e11.1 10 (0, 27) 14.3 (7.0) 13.4e15.3 14 (0, 28) A*, B**, C** ZBI-6 Mean (SD)** 95% CI Median (min, max) 6.4 (4.9) 5.4e7.3 6 (0, 19) 8.2 (5.8) 7.2e9.2 8 (0, 23) 12.3 (6.0) 11.5e13.1 13 (0, 24) B**, C** ZBI-4 Mean (SD)** 95% CI Median (min, max) 4.8 (3.5) 4.2e5.5 5 (0, 12) 6.1 (4.1) 5.4e6.8 6 (0, 16) 7.9 (3.8) 7.3e8.4 8 (0, 16) B**, C** ZBI-1 Mean (SD)** 95% CI Median (min, max) 1.0 (1.2) 0.8e1.3 1 (0, 4) 1.7 (1.3) 1.5e2.0 2 (0, 4) 2.1 (1.3) 1.9e2.2 2 (0, 4) A**, C** ZBI-22 Mean (SD)** 95% CI Median (min, max) 23.2 (13.4) 20.7e25.8 22 (0, 66) 27.9 (16.4) 25.0e30.7 26 (0, 73) 39.1 (17.3) 36.8e41.4 39 (5, 80) B**, C** *P ! 0.05, **P ! 0.01. Abbreviations: ABI, acquired brain injury; SD, standard deviation; CI, confidence interval; min, minimum; max, maximum; a The mean difference between three groups was tested using KruskaleWallis nonparametric ANOVA. b Multiple comparisons were made by Wilcoxon two-sample test, and type 1 error was controlled using Bonferroni method. A: cancer vs. dementia; B: cancer vs. ABI; C: dementia vs. ABI; only significant pairwise differences were presented. were similar to those in Table 3 separately for men and women, for those older and younger than 70 years, and for higher and lower burdened carers. The most optimal combination of sensitivity and specificity, as visualized from ROC curves (Fig. 1), was 92% and 94% for ZBI-12 (cutoff score: 12), 82% and 92% for ZBI-8 (cutoff score: 6), 95% and 86% for ZBI-7 (cutoff score: 7), 91% and 91% for ZBI-6 (cutoff score: 6), 88% and 85% for ZBI-4 (cutoff score: 4), and 91% and 53% for ZBI-1 (cutoff score: 1). All shorter versions were overall successful in differentiating low- and high-burden individuals with all AUCs well above 0.90. The short-form version with the best discriminative ability was ZBI-12 and that with the lowest was ZBI-1. ZBI-6 performed slightly better than ZBI-8 and to the same level as the ZBI-7. 4. Discussion We tested and validated six short forms of the ZBI in three caregiving populations. In all groups, there was a wide range of scores for the ZBI-22; therefore, the short forms were tested in samples reporting varying caregiver burden. However, the highest burden scores were in the dementia and the ABI groups, and we were not able to test burden scores above 34 in the advanced cancer group. It may be that caregiver burden using ZBI was lower in advanced cancer compared with dementia and ABI because of the lower levels of cognitive disturbance or greater specialist palliative support for the cancer carers (the cancer carers were sampled from palliative care services) [4,22,24,25]. However, it may equally be because of ZBI failing to measure some aspects of caregiver burden in advanced cancer. Caregiver burden is a complex construct. It has been described as having physical, social, financial, and emotional components, as well as leading to relationship and personal strain [16]. Some measures seek to capture ‘‘burden’’ and others ‘‘strain’’ [7e9]. More recently measures to capture carer positivity and satisfaction have been developed [36]. Which components of burden are present and whether these are different across different conditions are important questions and need to be the subject of future research. Three key findings emerge from our analysis. First, we found high levels of validity (with correlations ranging from 0.74 to 0.97) for all the short forms compared with ZBI-22 in three diagnostic groups with the only exception of the one-item version in cancer. The ZBI-12 has the highest validity (rho 5 0.95e0.97), and this is consistent across advanced cancer, dementia, and ABI samples. In our populations, the performance of the ZBI-8 and the ZBI-4 are almost identical and slightly worse than that of ZBI-6 in both 540 I.J. Higginson et al. / Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 63 (2010) 535e542 Table 3 Spearman correlation coefficients (95% CI) between full and short-form versions of ZBI and Cronbach’s alpha of all versions of ZBI Cancer Dementia ABI Version Rho (95% CI) Alpha Rho (95% CI) Alpha Rho (95% CI) Alpha ZBI-12 ZBI-8 ZBI-7 ZBI-6 ZBI-4 ZBI-1 ZBI-22 0.95 (0.92e0.96) 0.86 (0.80e0.90) 0.90 (0.86e0.93) 0.89 (0.84e0.93) 0.88 (0.82e0.91) 0.63 (0.50e0.73) d 0.85 0.74 0.82 0.78 0.69 NA 0.88 0.96 (0.94e0.97) 0.90 (0.87e0.93) 0.94 (0.92e0.96) 0.94 (0.91e0.95) 0.89 (0.85e0.92) 0.74 (0.66e0.81) d 0.87 0.80 0.86 0.83 0.78 NA 0.91 0.97(0.97e0.98) 0.93 (0.90e0.94) 0.95 (0.94e0.96) 0.95 (0.93e0.96) 0.92 (0.89e0.93) 0.78 (0.73e0.83) d 0.89 0.89 0.90 0.88 0.79 NA 0.93 Abbreviation: NA, not applicable. correlation and ROC analysis. Although the correlations between short and long forms appeared to be slightly and consistently stronger for the ABI group, and lowest in the advanced cancer group, the differences were marginal, not significant, and could be an artifact of the narrow range of scores for the cancer group. Second, we found high internal consistency of all versions of the ZBI, suggesting that some items are redundant and short forms can be used. Only the ZBI-4 had lower, but still good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha: 0.69e0.79) in the cancer group. Third, as we planned our analysis, we found confusions in the categorization of the role and personal strain subscales. Given the variability regarding the subscales and the high internal consistency of the full Zarit scale and all the short forms, we doubt that using the ‘‘personal’’ and ‘‘role’’ strain subscales has either face or psychometric validity [30]. The choice of ZBI version should be based on the specific aims of the research. For most situations, 12-item ZBI should have comparable performance with the full version with the differentiating capacity close to 1. For situations requiring rapid identification of caregiver burden, for example, screening for assessment or referral, four-item and even one-item versions will be the ideal choice, given their simplicity and optimal combination of high sensitivity (O80%) and high specificity (O50%) as evident by the ROC curves. Given that burden is multidimensional, the success of the single- and four-item versions surprised us. Although the ZBI-8 has more items, it did not exhibit any superiority over the ZBI-7 or the ZBI-6 in psychometric characteristics and differential ability. An earlier small study reported a perfect performance of the ZBI-7 with 100% sensitivity and 100% specificity in the palliative care setting [20]. The validation of the ZBI-7 in our larger study was close to thisd90% specificity at the sensitivity level of 90% (Fig. 1). However, we also found that, compared with the ZBI-7, excluding the ‘‘global burden question’’ did not compromise the ability of the ZBI-6 to distinguish carers with burden from those without, and results were almost equal to ZBI-12 (Fig. 1). Therefore, when investigators need to keep the number of questions short, the ZBI-6 appears to be a good choice. Short forms to assess caregiver 1.0 0.9 0.8 Sensitivity 0.7 0.6 0.5 0.4 0.3 AUC (95%CI) 0.2 ZBI- 1: 0.90(0.87-0.93) ZBI- 6: 0.98(0.97-0.99) ZBI- 8: 0.97(0.96-0.98) 0.1 0.0 0.0 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 0.5 ZBI- 4: 0.94(0.92-0.96) ZBI- 7: 0.98(0.96-0.98) ZBI-12: 0.99(0.98-0.99) 0.6 0.7 0.8 0.9 1.0 1-Spectificity Fig. 1. Receiver operating characteristic curves for various short-form versions of the Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI) and areas under the curve (AUC, 95% confidence interval [CI]). A total score of 21 on the full-scale ZBI as the cutoff value between low and high burden [18]. I.J. Higginson et al. / Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 63 (2010) 535e542 burden may be important to ensure feasible collection of datadburdened carers often focus on the needs of the patients whom they care for and not their own experiences and stresses related to caring [37] and may not wish to spend time completing anything but the briefest questionnaire. When using short-form versions of the ZBI as a screening test, sensitivity and specificity are standard measures for the diagnostic performance compared with the gold standarddZBI-22 [38]. However, these two measures are inversely related. Increasing one measure (by changing the cutoff value) results in a decrease in the other. Which one is more important is a question that can only be answered in the context in which it is used. Often a balance is needed. For example, sensitivity is important when identifying highly burdened carers (as measured by the summary score of the ZBI), because they can be offered more support that is unlikely to do harm [39]. However, when resources are scarce or if carers felt they were ‘‘labeled’’ as not coping by false-positive screening results, specificity is more important than sensitivity. It should be noted however that, in this study, we were primarily testing the performance of short forms of the ZBI as a screening tool. In clinical practice, a wider exploration of the components contributing to burden may be needed. Ideally, qualitative or cognitive interviewing would be needed to establish if all relevant aspects for caregiver burden are included. We recognize several limitations for this study. First, the performance comparisons were evaluated with cross-sectional data; therefore, they provide no information on short forms’ responsiveness to change (an essential psychometric property in intervention and longitudinal studies) [40]. Three of the original studies collected data at several time points; we are planning to use these data to assess the adequacy of short-form ZBI to detect change. Second, our analyses were restricted to the limited number of common demographic variables in the pooled data set; therefore, we could not make detailed performance comparisons across subsamples. Third, our validation was based on a comparison between short forms of ZBI with the full 22-item version, and thus makes an assumption that ZBI-22 accurately captures caregiver burden. Ideally, we would have assessed the short-form versions with other measures of burden or against clinical findings, but this would have required more intensive data collection among burdened carers, which may not have been feasible. Our data only allow conclusions to be drawn about the short-form versions of ZBI compared with the full version. 5. Conclusions We found strong validity and internal consistency for each of the short-form versions in all three samples. The 541 ZBI-12 is suitable in all situations, whereas the ZBI-7 or the ZBI-6 is suitable when a fewer-question version is needed, for example, in palliative care setting. The ZBI-7 is equivalent to the ZBI-6 although with one more question. The ZBI-4 and ZBI-1 may be useful when a very short screening instrument is needed, but the ZBI-1 may be less valid in cancer. Acknowledgments We thank the patients, carers, staff, and volunteers who participated in the original studies, including (1) six day and home hospice and palliative care services which recruited and interviewed patients and carers and Danielle Goodwin and other interviewers in the study; (2) two home palliative care services in London, Celia Leam and Liz Taylor who worked with us to recruit patients, and Alison Pearce (research assistant); (3) Research assistants Shehla Kazim, Amanda Tadrous, and Joel Sheridon and representatives of Headway, the Encephalitis Society and the Meningitis Trust, who helped to disseminate information about the ABI study to carer participants; (4) Community Mental Health Teams for Older Adults in the South London and Maudsley Mental Health Trust and the research workers Beth Foley and Louise Atkins. In addition, we thank the funders of the original studies: the NHS Executive (London and South East) for funding projects 1 and 2, the Department of Health (R&D grant 030/0066) for project 3, and the Department of Health, Policy Research Programme for project 4. Dr. Gao Wei is 50% supported by the National Cancer Research Institute, UK, a part of the ‘‘COMPlex interventions: Assessment, trialS and implementation of Services in Supportive and Palliative Care (COMPASS)’’ collaborative. We also thank Professors Peter Fayers, Gordon Murray, and Julia Brown for their helpful comments to improve this manuscript. References [1] Charlton R. Palliative care in non-cancer patients and the neglected caregiver. J Clin Epidemiol 1992;45:1447e9. [2] Hung SY, Pickard AS, Witt WP, Lambert BL. Pain and depression in caregivers affected their perception of pain in stroke patients. J Clin Epidemiol 2007;60:963e70. [3] Maher J, Green H. Carers 2000. Office for National Statistics. London: The Stationary Office; 2002. [4] The Resource Implications Study Group of the MRC Study of Cognitive Function and Aging (RIS MRC CFAS). Psychological morbidity among informal caregivers of older people: a 2-year follow-up study. The Resource Implications Study Group of the MRC study of cognitive function and ageing (RIS MRC CFAS). Psychol Med 2000;30:943e55. [5] Harding R, Higginson IJ. What is the best way to help caregivers in cancer and palliative care? A systematic literature review of interventions and their effectiveness. Palliat Med 2002;17:63e71. [6] Harding R, Higginson IJ, Leam C, Donaldson N, Pearce A, George R, et al. Evaluation of a short-term group intervention for informal 542 I.J. Higginson et al. / Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 63 (2010) 535e542 carers of patients attending a home palliative care service. J Pain Symptom Manage 2004;27:396e408. [7] Harvey K, Catty J, Langman A, Winfield H, Clement S, Burns E, et al. A review of instruments developed to measure outcomes for carers of people with mental health problems. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2008;117:164e76. [8] Visser-Meily JM, Post MW, Riphagen II, Lindeman E. Measures used to assess burden among caregivers of stroke patients: a review. Clin Rehabil 2004;18:601e23. [9] Mularski RA, Dy SM, Shugarman LR, Wilkinson AM, Lynn J, Shekelle PG, et al. A systematic review of measures of end-of-life care and its outcomes 3. Health Serv Res 2007;42:1848e70. [10] Goldstein NE, Concato J, Fried TR, Kasl SV, Johnson-Hurzeler R, Bradley EH. Factors associated with caregiver burden among caregivers of terminally ill patients with cancer. J Palliat Care 2004;20:38e43. [11] Schneider J, Hallam A, Murray J, Foley B, Atkin L, Banerjee S, et al. Formal and informal care for people with dementia: factors associated with service receipt. Aging Ment Health 2002;6:255e65. [12] Alvarez-Ude F, Valdes C, Estebanez C, Rebollo P. Health-related quality of life of family caregivers of dialysis patients. J Nephrol 2004;17:841e50. [13] Zarit SH, Reever KE, Bach-Peterson J. Relatives of the impaired elderly: correlates of feelings of burden. Gerontologist 1980;20: 649e55. [14] Gort AM, Mingot M, Gomez X, Soler T, Torres G, Sacristan O, et al. Use of the Zarit scale for assessing caregiver burden and collapse in caregiving at home in dementias. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2007;22: 957e62. [15] O’Rourke N, Tuokko HA. The relative utility of four abridged versions of the Zarit Burden Interview. J Ment Health Aging 2003;9: 55e64. [16] Chenier MC. Review and analysis of caregiver burden and nursing home placement. Geriatr Nurs 1997;18:121e6. [17] Bachner YG, O’Rourke N. Reliability generalization of responses by care providers to the Zarit Burden Interview. Aging Ment Health 2007;11:678e85. [18] Zarit SH, Orr RD, Zarit JM. The hidden victims of Alzheimer’s disease: families under stress. New York: New York University Press; 1985. [19] Bedard M, Molloy DW, Squire L, Dubois S, Lever JA, O’Donnell M. The Zarit Burden Interview: a new short version and screening version. Gerontologist 2001;41:652e7. [20] Gort AM, March J, Gomez X, de MM, Mazarico S, Balleste J. [Short Zarit scale in palliative care]. Med Clin (Barc) 2005;124:651e3. [21] Arai Y, Tamiya N, Yano E. [The short version of the Japanese version of the Zarit Caregiver Burden Interview (J-ZBI_8): its reliability and validity]. Nippon Ronen Igakkai Zasshi 2003;40:497e503. [22] Goodwin DM, Higginson IJ, Myers K, Douglas H-R, Normand C. Effectiveness of palliative day care in improving pain, symptom control and quality of life. J Pain Symptom Manage 2003;25:202e12. [23] Higginson IJ, Donaldson N. Relationship between three palliative care outcome scales. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2004;2:68e75. [24] Jackson D, Turner-Stokes L, Murray J, Leese M, McPherson KM. Acquired brain injury and dementia: a comparison of carer experiences. Brain Inj 2009;23:1e12. [25] Banerjee S, Murray J, Foley B, Atkins L, Schneider J, Mann A. Predictors of institutionalisation in people with dementia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2003;74:1315e6. [26] Knowles ES, Condon CA. Why people say ‘‘Yes’’: a dual-process theory of acquiescence. J Pers Soc Psychol 1999;77:379e86. [27] Shaffer JP. Multiple hypothesis-testing. Annu Rev Psychol 1995;46: 561e84. [28] Whitlatch CJ, Zarit SH, von EA. Efficacy of interventions with caregivers: a reanalysis. Gerontologist 1991;31:9e14. [29] Hebert R, Bravo G, Preville M. Reliability, validity and reference values of the Zarit Burden Interview for assessing informal caregivers of community-dwelling older persons with dementia. Can J Aging 2000;19:494e507. [30] Knight BG, Fox LS, Chou CP. Factor structure of the burden interview. J Clin Geropsychol 2000;6:249e58. [31] O’Rourke N, Tuokko HA. Psychometric properties of an abridged version of The Zarit Burden Interview within a representative Canadian caregiver sample. Gerontologist 2003;4:121e7. [32] Terwee CB, Bot SD, de Boer MR, van der Windt DA, Knol DL, Dekker J, et al. Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. J Clin Epidemiol 2007;60: 34e42. [33] Nunnally JC, Bernstein IH. Psychometric theory. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1994. [34] Coffin M, Sukhatme S. Receiver operating characteristic studies and measurement errors. Biometrics 1997;53:823e37. [35] Weinstein MC, Fineberg HV, Elstein AS, Frazier HS, Neuhauser D, Neutra RR, et al. Clinical decision analysis. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1980. [36] Lim JW, Zebrack B. Caring for family members with chronic physical illness: a critical review of caregiver literature. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2004;2:50. [37] Harding R, Higginson I. Working with ambivalence: informal caregivers of patients at the end of life. Support Care Cancer 2001;9: 642e5. [38] Bossuyt PM, Reitsma JB, Bruns DE, Gatsonis CA, Glasziou PP, Irwig LM, et al. Towards complete and accurate reporting of studies of diagnostic accuracy: the STARD initiative. Ann Intern Med 2003;138:40e4. [39] Fletcher RH, Fletchher SW. Prevention. In: Fletcher RH, Fletchher SW, editors. Clinical epidemiology: the essentials. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005. p. 158e61. [40] Kirshner B, Guyatt G. A methodological framework for assessing health indices. J Chronic Dis 1985;38:27e36.